Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Postcolonial Reading of Blood Diamond

Hochgeladen von

Pramod Enthralling EnnuiOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Postcolonial Reading of Blood Diamond

Hochgeladen von

Pramod Enthralling EnnuiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

INTRODUCTION Post-colonialism loosely designates a set of theoretical approaches which focus on the direct effects and aftermaths of colonization.

It also represents an attempt at transcending the historical definition of its primary object of study toward an extension of the historic and political notion of "colonizing" to other forms of human exploitation, normalization, repression and dependency. Post-colonialism forms a composite but powerful intellectual and critical movement which renews the perception and understanding of modern history, cultural studies, literary criticism, and political economy. Rejecting the Eurocentric Universalism it asserts that in the literary and cultural productions of West, East becomes the repository or projection of those aspects of themselves which Westerners do not choose to acknowledge. As pointed out by Edward Said in his work Orientalism the Orient features in the westerners mind as a sort of surrogate and even underground self. (Literature in the Modern World, 236). At the same time the East is seen as a fascinating realm of the exotic, the mystical and the seductive. The people there are often represented as homogenous mass, sans individuality or intellect, who act according to their instinctive emotions rather than by conscious choices or decisions.

Representation is presently a much debated topic, no t only in postcolonial studies and academia, but in the larger cultural milieu. Said in his analysis of representations of Orient in Orientalism, emphasizes the fact that representation can never be exactly realistic: In any instance of at least written language, there is no such thing as delivered presence, but a re-presence, or a representation. The value, efficacy, strength, apparent vivacity of a written statement about the Orient therefore relies very little, and cannot instrumentally depend, on the Orient as such. On the contrary, the written statement is a presence to the reader by virtue of its having excluded, displaced, made superergotary any such real thing as the Orient. (21) Representations then can never really be natural depictions of the Orient. Instead, they are constructed images, images that need to be interrogated for their ideological content. There remains always an element of interpretation involved in all representation. Ella Shohat claims that we should constantly question and analyse each filmic and academic utterance not only in terms of who represents but also in terms of who is being represented for what

purpose, at which historical moment, for which location, using which strategies, and in what tone of address. This paper is a postcolonial reading of the 2006 Hollywood film Blood Diamond directed and co-produced by the American film maker Edward Zwick. Set in the background of Civil War in Sierra Leone the film throws light into certain political and sociological problems in Africa. The title refers to blood diamonds which are diamonds mined in African war zones and sold to finance the conflicts and profit the war lords and diamond companies across the world. Analyzing the representation of the people and issues in Sierra Leone the study argues how the film, despite its message for freedom and betterment of Africa, falls in the same pit of its predecessors in its strategy and final rendering.

Blood Diamond: Colonialism Re-visiting

On the surface level, Blood Diamond is an adventure film, mixed with a liberal message. But on a deeper level, it functions in much the same manner as earlier, colonialist texts such as Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness in its depiction of Africa. Blood Diamond contains all the key generic characteristics of a Hollywood feature film. Set in Sierra Leone during the 1999 civil war, the film raises the issues of diamond smuggling and child soldiers through the story of Soloman Vandy whose village is attacked by rebel soldiers at the outset, and Danny Archer, a mercenary and diamond smuggler. During an attempt to save his family, Vandy is captured by the rebels and taken as a slave to work in the diamond fields. During his labours, Vandy finds a particularly large stone, risks his life to take it out of the fields and buries it nearby shortly before being captured and imprisoned by government troops. Danny Archer, a white 'Rhodesian', likewise in prison for diamond smuggling, hears the incensed ranting and threats of rebel guard Captain Poison (David Harewood) about the stone. He arranges for Vandy's release from prison, and proceeds to threaten, manipulate and eventually bribe Vandy (with the lure of finding his family) to take him to the diamond. With the help of an American journalist Maddy Bowen they find the whereabouts of his family. And after much struggles they reach the diamond

and manage to get it, overcoming the threats of Colonel Coetzee who is the operator of a private mercenary army and the military/ideological mentor for Archer. In spite of these valorous fights and final reconciliation with his own morality Archer loose his life to a bullet wound. The film ends with Vandys meeting his family and him being appreciated by the delegates in Kimberly Process. Along with its adventurous story and commendable cinematography the film projects some pseudo-liberal messages. It opens into the serenity and warmth of Solomons hovel and moves abruptly to the brutality of the civil war, which forms the major backdrop of the movie. Without sparing a single shot to inquire about or to explain the internal political struggles of Sierra Leone the narrative takes immense pleasure in depicting it as a mindless frenzy (Achebe 1997)of the Africans. Archer asserts that "People here [in Africa] kill each other as a way of life. It's always been like that," and while Bowen counters that "not all Africans kill each other as a way of life," much of this film precisely depicts Africans killing one another, rendering it more in keeping with Archer's view than Bowen's. Archer, Right from his introduction scene in the aircraft, is made to hold the central position in the narrative. The narrative here explicitly states that the implied audience of the film is the white bourgeoisie class in America as well as in

rest of the Europe. The implied white audience find it easy to identify with this white protagonist and everything is set to colonize the black/non-whites with their own land and culture. Archers morally compromised nature is explained away by his bitter childhood experiences. In their encounter with the white superiority of Archer the blacks look like fools. Archer with his astuteness and intelligence seems to have all the qualities of a traditional master and this prompts Soloman to be his slave without much reluctance. Solomans refusal to obey the commands of Archer often creates a frustration not only in Archers mind but in the minds of audience also, which in turn exposes who the narrative implies its expected audience to be. At the end of the film Archer emerges as a Christ figure sacrificing his life for Soloman and his family emphasizing the view that the blacks can only be redeemed by a white man. In truth this act of benevolence of a dying man can never be called a sacrifice for he has no other choice but this. Vandy, through his positioning as the sympathetic family man and victim of circumstance, is cast as the moral centre of the film, and indeed, his attempts to reclaim his son from rebel brainwashing form the film's most poignant moments. Vandy who occupies one of only two main speaking

roles allocated to African characters (the other being his somewhat psychotic R.U.F nemesis), is not given much of an opportunity to critique the actions of those around him. Although he is in many ways the moral centre of the film, Vandy lacks power and often subjectivity, and is shuttled from white character to white character who offer to help him. He is "just another black man in Africa" as Archer puts it. Vandy is set up as a counterpoint to the brutal Captain Poison, and it is telling that while Poison rhetoricises about their nation, and hates the white man, Vandy, the 'good black man' sends his son to school to learn English, hoping that one day he will become a doctor. The African nationalist is thus the demonised one, while the positive African character is a colonial mimic man, seeking for his child to learn the language of the colonisers in order to attain social advancement. Vandy's determined placidity is broken in the latter half of the film with a scene in which he confronts his tormentor, Captain Poison, and the two fight in hand-to-hand combat. Vandy's outburst of rage is well-justified, but the manner in which this is presented is significant. The breaking of his composure forms a dramatic peak of the film, and the two wrestle in the mud, screaming, and with the psychotic expressions on their faces framed in close ups. Vandy in the kills Poison by hammering him with a shovel. Although this is the only man Vandy kills, unlike Archer who shoots a great

number of people throughout the course of the film, the distancing effected by the use of a gun, rather than the force necessitated by the use of a shovel, further renders this scene as visually animalistic, as it had from its opening close up on Vandy's face, teeth bared, eyes red, displaying all the markers of 'savagery' that one can see in Conrad's depictions of Africans. The end of the film shows Vandy, clad in a very expensive looking suit, being introduced by an ambassador who states, The third world is not a world apart, and the witness you hear today speaks on its behalf. Let us hear that voice. Let us learn from it, and let us ignore it no more. Ladies and gentlemen: Mr. Soloman Vandy. Conversely the film then ends without allowing Vandy to make any sort of a statement. The narrative takes great pains in silencing Vandy. Just like this final scene and in many other parts of the film, we do not hear his voice or his perspective. One could argue that this is as an acknowledgement on the part of the filmmakers that they do not, indeed, have an authentically African or third-world voice in this film, and implore its audience to listen to other messages from Africa. However, the lack of knowingness displayed by the rest of the film would seem to negate such a reading, and regardless,

where is one to find such a voice within our overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly economically privileged western popular culture? Blood Diamond also includes extended conversations between Archer and Bowen where the motives of these two different types of white characters are questioned, and their exploitative roles in Africa discussed. Whether this be Archer's overt smuggling and gun-running to both sides of the conflict, or Maddy's journalistic exploitation of war and human suffering in the name of a story, such critique stays firmly in the hands of the white characters. Bowen critiques Archer, who critiques her in turn. Despite the difference in their motives and strategies both relies on the victim position of the blacks for their existence. Just like any other narrative about the Orientals, Africa is conceived here by the racist cultural imagination of west as a place of chaos and irrationality, implying that there is something uniquely problematic and inherently irredeemable about the place. Africa is presented as a hell where one cant have a peaceful existence. After having told Bowen of the gruesome deaths of his parents, Danny Archer refers to Africa as a "godforsaken continent," proclaiming that "Sometimes I wonder if God will ever forgive us for what we have done to each other. Then I look around and I realise: God left this

10

place a long time ago." This statement, which featured prominently in the trailer for the film, certainly conveys the desolation and hopelessness of the situation, but it also hearkens back to the representation of Africa as the 'heathen' place it was considered in the colonialist, missionary imagination, and could further be read to imply that this 'God' who was indeed present and is now gone, was associated with white control and 'civilization.' This vision of Africa as a hellish heart of darkness is explicitly stated by Captain Poison when he says to Vandy "you think I am a devil, but only because I have lived in hell. I want to get out. You will help me, or your family will die!" These sorts of colonialist messages are further implicated by the presentation of Danny Archer as the 'true' African who can never leave the continent. Early in the film, Archer is told by Colonel Coetzee that "this red earth, it's in our skinThis is home. You'll never leave Africa." And indeed, while Soloman Vandy and his family happily escape to England, and Poison is willing to kill in order to "get out," Archer cannot leave, affirming that "I'm exactly where I'm supposed to be," as he lies dying. As the music rises and we see a shot of his blood dribbling into the soil, he rubs it between his hands - the 'authentic' African who cannot exist outside Africa. Visually too, Africa is portrayed in this film as the chaotic, fevered Heart of Darkness of Joseph Conrad's imaginings. Camera restricts the

11

frame from moving away from the ideologically interpellated visuals and instead intends to hang around either the exotic wilderness of the African forests or the gruesome images of the refugee camps. With its prototypically affirmative Hollywood structure, and focus on an individual who escapes to a world of peace and designer suits, it sets up a dichotomy between Africa and 'civilized' London in much the same way as Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness projects the image of Africa as 'the other world,' the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilization, a place where man's vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant beastiality" (Achebe, 1977).

12

Conclusion The expos of the diamond trade that Blood Diamond presents does have an explicitly political purpose, but it doesn't ask its audience to undertake too much questioning of their own actions or those of their governments. The message not to buy diamonds from conflict zones seen at the end of the film allows the audience to feel good, to feel that they have 'helped' Africa by refusing to buy these products. When Archer questions whether Bowen is "exploiting [Vandy's] grief," Bowen describes her writing as "like one of those infomercials, little black babies with swollen bellies and flies in their eyesI'm sick of writing about victims but its all I can fucking doBecause I need factsPeople back home wouldn't buy a ring if they knew it cost someone else their hands." This speech positions the film Blood Diamond as offering just those facts that will be able to change the situation via boycott activism, eliding the very real problems created by colonialism. It is indeed the case that Blood Diamond itself functions in much the same way as a World Vision commercial does. Blood Diamond presents its audience with a vision of a world of suffering, complete with a happy ending, and an epilogue that offers its audience an opportunity to

13

make some small gesture to help which will salve their consciences and allow them to think upon the subject, and world's inequities, no longer. While ascribing to these conventions of the genre was no doubt necessary in order to gain funding and audiences for this project, the effect remains the same. The audience's journey from recognition to 'action' is narratively encouraged by the redemption of the two white heroes (both played by wellknown American actors) through their assistance in reuniting Vandy with his family and exposing the trade in 'blood diamonds.' But the issue goes no further. The film fails to acknowledge the role that colonialism, and the destruction of social structures and the pillaging of resources it undertakes, has played in creating this climate of unrest, violence and poverty. Indeed, it takes this lack of acknowledgement a step further, and through its Eurocentric (and at times explicitly colonialist) narrative, images and dialogue, it renders a portrait of Africa little different from earlier western depictions. The most disturbing, explicitly colonialist and racist message of the film, however, is placed in the mouth of the African protagonist Soloman Vandy. He says to Archer "I understand why people want diamonds, but how can my own people do this to each other? I know good people who say there is

14

something wrong with us, besides our black skin, that we were better off when the white men ruled." It is this statement that echoes across the film, acting as a justification of and incitement to colonialism, disavowing the role colonialism has played in creating Africa's problems, and proclaiming that Africans are childlike or savage beings that need white masters to rule over them in order to stop them from killing one another: a chilling message from a contemporary Hollywood feature film, and a reflection of how much western societies' attitudes have cycled back to the colonialist mentalities of time past.

15

Bibliography Swick, Edward. Dir. Blood Diamond. Warner Bros. 2006 Beirne, Rebecca. Blood Diamond A review. 8March 2007. web. 17 July 2010. Achebe, Chinua. (1977) An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's Heart of Darkness in Massachusetts Review. 6 March 2007. web. 18 July 2010

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Notes On As Short StoriesDokument12 SeitenNotes On As Short StoriesFarah NoreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Four QuartetsDokument2 SeitenFour QuartetsjavedarifNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is RepresentationDokument3 SeitenWhat Is RepresentationrobynmdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tyler Barton Mrs. Carter AP Lit and Comp 3/6/14 Elements of Poetry in The TygerDokument3 SeitenTyler Barton Mrs. Carter AP Lit and Comp 3/6/14 Elements of Poetry in The TygerTylerjamesbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arthur Miller PresentationDokument9 SeitenArthur Miller Presentationapi-266422057Noch keine Bewertungen

- This Boy's Life Essay2 DraftDokument2 SeitenThis Boy's Life Essay2 DraftIzzy MannixNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Position PaperDokument3 SeitenHow To Write A Position PaperAndrés MatallanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ENG 426 Term Paper - Sadia AfrinDokument6 SeitenENG 426 Term Paper - Sadia AfrinSadia AfrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of Absurdity and Existentialism inDokument9 SeitenElements of Absurdity and Existentialism inManidipa Bose100% (1)

- Bitka Na MoruDokument20 SeitenBitka Na MoruBrian Kirk100% (1)

- Narrative Techniques in Heart: of DarknessDokument7 SeitenNarrative Techniques in Heart: of DarknessMorshed Arifin Uschas100% (1)

- Codex Space MarinesDokument33 SeitenCodex Space MarinesCarlosFerraoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rebalanced Compendium PDFDokument79 SeitenRebalanced Compendium PDFChelliuAnthropósNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indulekha (First Novel of Malayalam) PDFDokument210 SeitenIndulekha (First Novel of Malayalam) PDFMunniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andrew Marvell's "To His Coy Mistress" - Mythological Approach - Archetypal Elements inDokument3 SeitenAndrew Marvell's "To His Coy Mistress" - Mythological Approach - Archetypal Elements inBassem KamelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Streetcar Named Desired Key QuotesDokument5 SeitenStreetcar Named Desired Key QuotesKai Leng ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instant Download Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology 3rd Edition Nelms Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDokument32 SeitenInstant Download Nutrition Therapy and Pathophysiology 3rd Edition Nelms Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDeborahBenjaminjgdk100% (4)

- H & R GalleryDokument13 SeitenH & R GalleryPierre-jean Ternamian100% (1)

- AI Application in MilitaryDokument26 SeitenAI Application in MilitaryZarnigar Altaf85% (13)

- Overlord 02 - The Dark WarriorDokument231 SeitenOverlord 02 - The Dark Warrioralexdaman2907100% (4)

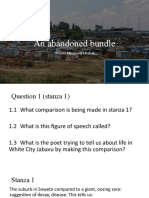

- An Abandoned BundleDokument7 SeitenAn Abandoned Bundlejenny brandtNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Clod and The PebbleDokument4 SeitenThe Clod and The PebbleZenobiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soviet Aims in Korea and The Origins of The Korean War, 1945-1950 New Evidence From Russian ArchivesDokument37 SeitenSoviet Aims in Korea and The Origins of The Korean War, 1945-1950 New Evidence From Russian ArchivesoraberaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bluest Eye: Autumn: Supporting QuoteDokument2 SeitenThe Bluest Eye: Autumn: Supporting QuoteLuka MaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On Bangsamoro Youth, Bangsamoro's FutureDokument3 SeitenEssay On Bangsamoro Youth, Bangsamoro's Futurealican karimNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Outsider As ExistentialistDokument2 SeitenThe Outsider As ExistentialistNoor Zaman Jappa100% (1)

- Plato's Apology Study GuideDokument2 SeitenPlato's Apology Study GuideRobert FunesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 'This Boy's Life': Is Rosemary A Good Mother To Jack?Dokument3 Seiten'This Boy's Life': Is Rosemary A Good Mother To Jack?Chien He Wong100% (1)

- BelovedDokument4 SeitenBelovedcrazybobblaskeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Othello,: The Moor of VeniceDokument3 SeitenOthello,: The Moor of VeniceLia Irennev100% (1)

- Ode Intimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early ChildhoodDokument5 SeitenOde Intimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early ChildhoodPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Farewell To Arms Documentary ScriptDokument4 SeitenA Farewell To Arms Documentary Scriptapi-267938400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comments On Arthur Miller's 'Death of A Salesman', by Andries WesselsDokument3 SeitenComments On Arthur Miller's 'Death of A Salesman', by Andries WesselsRobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mystery and Suspense PresentationDokument10 SeitenMystery and Suspense PresentationPatryce RichterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Important QuestionsDokument4 SeitenImportant QuestionsSaba MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henrik IbsenDokument9 SeitenHenrik IbsenAyesha Susan ThomasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heart of Darkness - MaterialismDokument16 SeitenHeart of Darkness - MaterialismSumayyah Arslan100% (1)

- Hamlet EssayDokument5 SeitenHamlet EssayBen JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heart of Darkness Post Colonial ReadingDokument8 SeitenHeart of Darkness Post Colonial ReadingWilliam N. MattsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Proctor A Tragic HeroDokument4 SeitenJohn Proctor A Tragic Heroapi-317233224100% (3)

- Nietzsche's Three Steps To A Meaningful Life - Lessons From History - MediumDokument12 SeitenNietzsche's Three Steps To A Meaningful Life - Lessons From History - MediumRosa García MoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Notes09Dokument10 SeitenFinal Notes09blahman654Noch keine Bewertungen

- Play Project AssignmentDokument9 SeitenPlay Project AssignmentAmber Blackstar MagnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Crucible - Conflicts: " Proctor: It ' S Winter in Here Yet. " (51) : Refers To How John and Elizabeth'sDokument2 SeitenThe Crucible - Conflicts: " Proctor: It ' S Winter in Here Yet. " (51) : Refers To How John and Elizabeth'sOwen Zhao100% (1)

- How Is The Poem Phenomenal Woman' A Reflection of The Poet's Personal Life?Dokument5 SeitenHow Is The Poem Phenomenal Woman' A Reflection of The Poet's Personal Life?SourodipKundu100% (1)

- Camus and GodotDokument13 SeitenCamus and GodotAngelie Multani50% (4)

- DeconstructionDokument16 SeitenDeconstructionrippvannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hamlet A Tragic Hero?Dokument3 SeitenHamlet A Tragic Hero?Nikita145100% (1)

- Literary CriticismDokument2 SeitenLiterary CriticismJazzmin DulceNoch keine Bewertungen

- B.A Thesis - Waiting For GodotDokument27 SeitenB.A Thesis - Waiting For GodotEsperanza Para El MejorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hawthorne The Minister's Black VeilDokument2 SeitenHawthorne The Minister's Black VeilPremeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment of Popular Fiction Group 1Dokument6 SeitenAssignment of Popular Fiction Group 1Umair Ali100% (1)

- William FaulknerDokument2 SeitenWilliam FaulknerAngela91Noch keine Bewertungen

- Post-Colonialism in Coetzee's Waiting For The BarbariansDokument8 SeitenPost-Colonialism in Coetzee's Waiting For The BarbariansRohit VyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Farewell To ArmsDokument3 SeitenA Farewell To ArmsDelia ChiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Things Fall ApartDokument2 SeitenThings Fall ApartDin Tang VillarbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martin CarterDokument8 SeitenMartin CarterAshley Morgan100% (1)

- Mythology in TS Eliots The WastelandDokument5 SeitenMythology in TS Eliots The Wastelandamelie979Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Critic As An Artist Submitted By:saleema Kasi Submitted To: Ma'am ShaistaDokument8 SeitenThe Critic As An Artist Submitted By:saleema Kasi Submitted To: Ma'am ShaistaSaleema Kasi0% (1)

- TFA and CultureDokument14 SeitenTFA and CulturenrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critacal Analysis of 'Too Late' by Katlego ThobyeDokument4 SeitenCritacal Analysis of 'Too Late' by Katlego ThobyeKatlego Koketso ThobyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Criticism (Feminism)Dokument2 SeitenLiterary Criticism (Feminism)Jearica IcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper 3 - Things Fall ApartDokument14 SeitenPaper 3 - Things Fall Apartapi-348849664Noch keine Bewertungen

- Important Questions NovelDokument5 SeitenImportant Questions NovelHaji Malik Munir AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classical Drama AssignmentDokument5 SeitenClassical Drama AssignmentSarah Belle100% (1)

- The Importance of Being Earnest - EssayDokument3 SeitenThe Importance of Being Earnest - EssayconniieeeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Crucible AllegoryDokument4 SeitenThe Crucible AllegoryGaby UtraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defining Criticism, Theory and LiteratureDokument20 SeitenDefining Criticism, Theory and LiteratureSaravana SelvakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Galileo by Brecht AnalysisDokument3 SeitenGalileo by Brecht AnalysisKabirJaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sun Also Rises Is A Novel by American Writer Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)Dokument6 SeitenThe Sun Also Rises Is A Novel by American Writer Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961)Sk. Shahriar RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frankenstein Critical AnalysisDokument4 SeitenFrankenstein Critical Analysisapi-254111146Noch keine Bewertungen

- Colonialism, Racism and Representation:An IntroductionDokument7 SeitenColonialism, Racism and Representation:An Introductionmahina kpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postcolonialism-Essay FinalDokument2 SeitenPostcolonialism-Essay FinalJosh DavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crow's Last StandDokument1 SeiteCrow's Last StandPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- But Do Not So, I Love Thee in Such Sort, As Thou Being Mine, Mine Is Thy Good ReportDokument1 SeiteBut Do Not So, I Love Thee in Such Sort, As Thou Being Mine, Mine Is Thy Good ReportPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Your Attention PleaseDokument2 SeitenYour Attention PleasePramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonnet 32Dokument1 SeiteSonnet 32Pramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poem in OctoberDokument4 SeitenPoem in OctoberPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Complaint: by William WordsworthDokument1 SeiteA Complaint: by William WordsworthPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonnet 45 of ShakespeareDokument1 SeiteSonnet 45 of ShakespearePramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Narrow Fellow in The GrassDokument1 SeiteA Narrow Fellow in The GrassPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faith" Is Fine InventionDokument1 SeiteFaith" Is Fine InventionPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Out of The Cradle Endlessly RockingDokument5 SeitenOut of The Cradle Endlessly RockingPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Slumber Did My Spirit SealDokument1 SeiteA Slumber Did My Spirit SealPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biodiversity and Ecological Status of Iringole KavuDokument7 SeitenBiodiversity and Ecological Status of Iringole KavuPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kerala Style Aviyal: Ingredients NeededDokument1 SeiteKerala Style Aviyal: Ingredients NeededPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ode Intimations of ImmortalityDokument5 SeitenOde Intimations of ImmortalityPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- That Time of Year Thou Mayst in Me BeholdDokument1 SeiteThat Time of Year Thou Mayst in Me BeholdPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frost at MidnightDokument3 SeitenFrost at MidnightPrakash0% (1)

- Structure, Sign, and Play in The Discourse of The Human SciencesDokument14 SeitenStructure, Sign, and Play in The Discourse of The Human SciencesPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rava Kesari Recipe - IngredientsDokument1 SeiteRava Kesari Recipe - IngredientsPramod Enthralling EnnuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Porattu NadakamDokument31 SeitenPorattu NadakamPramod Enthralling Ennui25% (4)

- List of French Monarchs - WikipediaDokument19 SeitenList of French Monarchs - WikipediamangueiralternativoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization - Pros and Cons: Quality - Access To Success March 2018Dokument5 SeitenGlobalization - Pros and Cons: Quality - Access To Success March 2018Alexei PalamaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAW Fiction - Tired Old Man (Gary D Ott) - Big JohnDokument414 SeitenPAW Fiction - Tired Old Man (Gary D Ott) - Big JohnBruce ArmstrongNoch keine Bewertungen

- White Dwarf 474 - March 2022 (Ok Scan)Dokument154 SeitenWhite Dwarf 474 - March 2022 (Ok Scan)Guilherme Nobre DoretoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Codex Supplement: Imperial Fists: Designer'S NotesDokument3 SeitenCodex Supplement: Imperial Fists: Designer'S NotesИльяNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vol 12 No 1 Jan 1961Dokument12 SeitenVol 12 No 1 Jan 1961design6513Noch keine Bewertungen

- Inquiry Project TopicsDokument24 SeitenInquiry Project Topicsapi-202075414Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hammerhead Six - How Green Berets Waged An Unconventional War Against The Taliban To Win in Afghanistan's Deadly Pech Valley (PDFDrive)Dokument318 SeitenHammerhead Six - How Green Berets Waged An Unconventional War Against The Taliban To Win in Afghanistan's Deadly Pech Valley (PDFDrive)kristina PriscanNoch keine Bewertungen

- In War and After It A Prisoner Always - Reading Past The ParadDokument193 SeitenIn War and After It A Prisoner Always - Reading Past The ParadSun A Lee100% (1)

- Western Civilization Volume I To 1715 9th Edition Spielvogel Test BankDokument22 SeitenWestern Civilization Volume I To 1715 9th Edition Spielvogel Test Banktimothyamandajxu100% (21)

- PDF HandlerDokument51 SeitenPDF HandlerFernando AmorimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life of Tipu SultanDokument153 SeitenLife of Tipu SultanmuthuganuNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIST gAMEDokument7 SeitenLIST gAMEruncang tundangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Images Danville-Boyle County, Kentucky 2011Dokument56 SeitenImages Danville-Boyle County, Kentucky 2011Journal CommunicationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chuyên Nguyễn Trãi 11 DHBBDokument18 SeitenChuyên Nguyễn Trãi 11 DHBBHung Cg NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cuban RevolutionDokument7 SeitenThe Cuban RevolutionRisha OsfordNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Commitment by Robert Schelling.Dokument29 SeitenThe Art of Commitment by Robert Schelling.Gregory DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- KamraDokument12 SeitenKamramurad_warraichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crim Review DigestsDokument3 SeitenCrim Review DigestsElmer Barnabus100% (1)