Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Pension Funding Guarantee: An Irresponsible Plan

Hochgeladen von

Illinois PolicyOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Pension Funding Guarantee: An Irresponsible Plan

Hochgeladen von

Illinois PolicyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

illinois Policy Institute Special report

APRil 23, 2013 Pension Reform

The pension funding guarantee: an irresponsible plan

Diane Cohen, General Counsel, Liberty Justice Center of the Illinois Policy Institute

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This memo provides a review of the funding guarantee provisions found in the pension reform bills that currently are or have been under consideration by the Illinois General Assembly. Though each of these provisions vary somewhat, they all would constitutionally obligate the state to fund the state pension systems. The question of whether to support a funding guarantee provision should not be framed as one that asks whether the state should stand behind its pension funding obligations. Rather, this question is more responsibly and accurately framed as one that asks whether the state actually can stand behind the unpredictable obligations these proposals create. The following is an overview of the main points in the memo: Two sets of pension bills that currently are or have been before the Illinois General Assembly contain funding guarantee provisions: House Bill 3162 and Senate Bill 2404: Filed by state Rep. Jay Hoffman and state Sen. Linda Holmes, respectively. House Bill 3411 and Senate Bill 35: Filed by House Minority Leader Tom Cross and state Sen. Daniel Biss, respectively. The funding guarantee language in both sets of bills unambiguously creates a constitutionally enforceable contractual obligation by the state to make required funding contributions to the pension systems. The guarantee language would alter current law and legal precedent, which currently do not make the taxpayers the obligors of the state pension systems liabilities. It is possible that the courts could interpret the funding guarantee as consideration for prospective changes to pension benefits contained in the proposed bills, thus binding the state to those benefits in a way that does not currently exist. The states ability to unilaterally amend or repeal the funding guarantees in the future is unclear, at best. Both sets of bills would prioritize pension funding above all core government services, such as public safety, education, transportation and health care. This would essentially create a special class of beneficiaries to the detriment of every other Illinoisan. It is irresponsible for the state to guarantee an obligation over which it has no control. As long as Illinois maintains the unpredictable defined benefit pension structure, the state is providing an open-ended guarantee with the potential for severe and unforeseeable costs. The only real funding guarantee is one that puts employees in control of their own retirement through an automatic employer match in a defined contribution retirement savings system.

Additional resources: illinoispolicy.org/pensionreform 190 S. LaSalle St., Suite 1630, Chicago, IL 60603 | 312.346.5700 | 802 S. 2nd St., Springfield, IL 62704 | 217.528.8800

Funding guarantee legislation

House Bill 3162 and Senate Bill 2404, and House Bill 3411 and Senate Bill 35, are two sets of bills that currently are or have been under consideration by the Illinois General Assembly, which would amend the Illinois Pension Code1 to provide for a state funding guarantee for state worker pensions. A guarantee would contractually obligate the state to pay annual required contributions to bring the pension systems total assets up to 100 percent of the total liabilities by the year 2045 under HB 3162 and SB 2404, or by the year 2043 under HB 3411 and SB 35. While the language in each bill varies somewhat, each creates a constitutionally enforceable contractual obligation by the state to make required funding contributions.

Accordingly, in light of the clear and unambiguous contract language in all the guarantee provisions, those who claim that the provisions would not bind the state contractually have an uphill battle, at best, advancing this argument. These bills would alter the current state of the law and legislatively overrule Illinois Supreme Court precedent that holds that neither the Pension Code nor Art. XIII, Sec. 5 of the Illinois Constitution8 were intended to make taxpayers vis--vis the state the obligors of the states pension systems and that the only enforceable contractual relationship that exists is that which protects a pensioners right to receive earned benefits.9

The funding guarantee could impede future benefit reforms

The funding guarantee language could impede future benefit reforms. It is possible that the courts could interpret the funding guarantee as consideration for prospective changes to pension benefits contained in the proposed bills, thus binding the state to those benefits in a way that does not currently exist. The prevailing view in state courts across the country with the notable exception of about a dozen states is that prospective benefits may be unilaterally changed without consideration because they are unearned and thus do not rise to the level of a vested right. But funding guarantee language not only could expose the state to constitutional payment obligations that it cannot meet, but also could be interpreted to bind the state to the benefits contained in the bills now and in the future. Thus, under a funding guarantee the state not only loses any leverage it has to enact real pension reform going forward, but it also commits to a system that is literally bankrupting the state.

The pension funding guarantees create a new contractual obligation

HB 3162 and SB 2404 expressly refer to the funding guarantee as a contractual obligation and do so four times throughout the texts of the provisions. HB 3411 and SB 35 provide that the states contractual obligations established in the bill are protected and enforceable pursuant to the Contract Clause of the Illinois Constitution. This means the state would be b[inding] [itself] in a covenant not to take certain actions now or in the future. Therefore, funding guarantee language seems to be a deliberate effort to invoke the constitutional protections of the Contract Clause as security against repeal.2 HB 3162 and SB 2404 do not expressly refer to the state or federal contract clauses in connection with the establishment of the funding guarantee. But this omission is likely of no consequence as to whether the terms create a binding contract because of the states apparent adequate expression of an actual intent to bind itself to the funding guarantee obligations, which is made clear in both bills.3 Both the express language contained in the bills and the circumstances surrounding their consideration indicate that if the bills were enacted they would constitute binding state obligations, protected and enforceable by the federal and state constitutions. If the Illinois General Assembly did not bind itself contractually, the presumption would be that a law is not intended to create private contractual or vested rights but merely declares a policy to be pursued until the legislature shall ordain otherwise.4 Similarly, Policies, unlike contracts, are inherently subject to revision and repeal, and to construe laws as contracts when the obligation is not clearly and unequivocally expressed would be to limit drastically the essential powers of a legislative body.5 However, a statute is itself treated as a contract when the language and the circumstances evince a legislative intent to create private rights of a contractual nature enforceable against the State.6 And it long has been established that the Contract Clause limits the power of the States to modify their own contracts as well as to regulate those between private parties.7

Repealing the funding guarantees would be difficult, if not impossible

While it is true that a state contract may be modified, it is not as simple as passing legislation to repeal it or language contained therein. Despite the customary deference courts give to state laws directed to social and economic problems, courts will evaluate with particular scrutiny a modification of a contract to which the state itself is a party. 10 Any legislative alteration of the rights and remedies contained in the contract must be necessary and reasonable and of a . . . character appropriate to the public purpose justifying its adoption.11 Proponents of the funding guarantee provision who claim that it could be easily repealed or modified at any time will run up against contract clause jurisprudence. Indeed, the state already has the information it needs to know that perpetuating the defined benefit system and binding the state to a funding obligation is against the public interest. One need only look at the existing unfunded liability to see that the

public welfare is already being harmed. The funding guarantee provisions in these bills would just makes the existing crisis worse.

The funding guarantees put pensions above all core government services

Each of the pension reform bills creates an enforcement mechanism for the states funding obligations. HB 3411 gives the pension systems the right to bring a mandamus action in the circuit court to enforce the states obligation. HB 3411 also expressly subordinates all other state payments (with the exception of payments on bonded debt) to the payment of pension obligations and gives the circuit court authority to order a reasonable payment schedule to enable the State to make the required payment without significantly imperiling the public health, safety, or welfare. However, the courts authority is entirely discretionary and significantly imperiling is undefined. HB 3162, SB 2404 and SB 35 create a right for each member or annuitant to bring a cause of action in any judicial district in which a pension system maintains an office, if the system fails to bring an enforcement action. While SB 35 gives the court discretion to order a reasonable payment schedule to enable the state to make the required payment, neither SB 35 nor HB 3162 or SB 2404, accord the court discretion to order reasonable payments to avoid imperiling the public health, safety or welfare. While SB 35 subordinates all other state payments (with the exception of payments on bonded debt) to the payment of pension obligations, HB 3162 and SB 2402 do not. The practical effect of the pension funding guarantee is to create a special class of beneficiaries to the detriment of all other Illinoisans, including taxpayers and those who depend on government services. This runs contrary to the principles expressed in the preamble to the Illinois Constitution, which was established to: . . . provide for the health, safety and welfare of the people; maintain a representative and orderly government; eliminate poverty and inequality; assure legal, social and economic justice; provide opportunity for the fullest development of the individual; insure domestic tranquility; provide for the common defense; and secure the blessings of freedom and liberty to ourselves and our posterity. . . . 12

That is because as long as Illinois maintains the defined benefit model, the state will be unable to meet the funding obligations that go along with it due to the unpredictable assumptions on which pension obligations are based.13 It would be misleading for the state to take on these obligations that it knows and history shows it simply cannot meet.

Conclusion

If a client were seeking advice from a lawyer on whether to enter into the contracts created by both sets of bills with the clients life savings, childrens college savings accounts and the family home as collateral the only responsible recommendation would be dont do it. The client would be committing himself to financial obligations he could not meet and be in risk of financial insolvency. Likewise, the state should not sign off on this bad deal that puts taxpayers and core state services at risk. Illinois pensions are officially underfunded by $96 billion, but new accounting rules will put the liability at more than $200 billion.14 Given the flawed nature of defined benefit plans, there are no real mechanisms to stop that underfunding from growing. Therefore, if investment returns are subpar or if politicians continue to give away overly generous benefits, the unfunded liability will only go up, as will taxpayers financial obligations, no matter how much they may have already contributed. Once the state commits itself to the contractual guarantee obligation, as each of the bills clearly would, the state cannot simply amend or repeal the guarantee unilaterally without violating the contracts clauses in both the U.S. and Illinois Constitutions. Likewise, any hope for real reform will have been squandered, leaving little to no incentive for future changes to deal with what will be a certain and continued crisis. A funding guarantee would only provide another roadblock to real pension reform. The way out of the pension crisis is not a funding guarantee, but real benefit reform that does not make promises the state cannot keep. The only real, honest and responsible guarantee is one that puts employees in control of their retirement funds through a system of defined contributions, on both the employees and states part.

Guaranteeing the defined benefit pension model is irresponsible

The question of whether to support a funding guarantee provision should not be framed as one that asks whether the state should stand behind its pension funding obligations. Rather, this question is more responsibly and accurately framed as one that asks whether the state actually can stand behind the unpredictable obligations determined by a defined benefit model.

1 2

Illinois Pension Code, 40 ILCS 5/1-101, et seq.

Natl R.R. Passenger Corp. v. Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 470 U.S. 451, 470 (1985); see also U.S. Const. Art. 1, 10, cl. 1 (No State shall . . . pass any . . . Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts); and Illinois Const. Art. I, 16 (No . . . law impairing the obligation of contracts . . . shall be passed.).

3 4 5 6 7 8

Natnl R.R., 470 U.S. at 466-467. Id. at 465-66. Id. at 466. U.S. Trust Co. of New York v. New Jersey, 431 U.S. 1, 17 n. 14 (1977). Id. at 17.

Illinois Constitution Art. XIII, Sec. 5 provides: Membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired. People ex rel. Illinois Federation of Teachers, AFT, AFL-CIO v. Lindberg, 60 Ill. 2d 266, 273-75 (1975); see also McNamee v. Illinois, 173 Ill. 2d 433, 443-44 (1996).

9 10 11 12 13

Allied Structural Steel Co. v. Spannaus, 438 U.S. 234, 244 (1978). Id. (quoting U.S. Trust, 431 U.S. at 22). Illinois Constitution Preamble.

Robert Novy-Marx & Joshua Rauh, Public pension promises: How big are they and what are they worth? Journal of Finance, 66(4), (2011). Jonathan Ingram & Ted Dabrowski, Pension debt more than doubles under new rules, Illinois Policy Institute (2012), http://illinoispolicy.org/news/article.asp?ArticleSource=4986.

14

The Liberty Justice Center of the Illinois Policy Institute is a nonpartisan, nonprofit public interest litigation firm dedicated to advancing liberty, limiting government and protecting freedoms guaranteed under the Illinois and U.S. Constitutions.

Guarantee of quality scholarship

The Illinois Policy Institute is committed to delivering the highest quality and most reliable research on matters of public policy. The Institute guarantees that all original factual data (including studies, viewpoints, reports, brochures and videos) are true and correct, and that information attributed to other sources is accurately represented. The Institute encourages rigorous critique of its research. If the accuracy of any material fact or reference to an independent source is questioned and brought to the Institutes attention in writing with supporting evidence, the Institute will respond. If an error exists, it will be corrected in subsequent distributions. This constitutes the complete and final remedy under this guarantee.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Illinois Senate Bill 1Dokument482 SeitenIllinois Senate Bill 1Illinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contracting For Success: An Introduction To School Service PrivatizationDokument81 SeitenContracting For Success: An Introduction To School Service PrivatizationIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Open Letter To The General Assembly On The Progressive Income Tax From Illinois Local GovernmentsDokument2 SeitenAn Open Letter To The General Assembly On The Progressive Income Tax From Illinois Local GovernmentsIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annual Cost of Illinois LawmakersDokument24 SeitenAnnual Cost of Illinois LawmakersIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hidden Bill: Chicago Taxpayers and The Looming CrisisDokument32 SeitenThe Hidden Bill: Chicago Taxpayers and The Looming CrisisIllinois Policy100% (1)

- Letter From Sen. Richard DurbinDokument2 SeitenLetter From Sen. Richard DurbinIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amendment of Chapter 4-64 of Municipal Code by Adding New Section 4-64-098 Regarding Flavored Tobacco Products and Amending Section 4-64-180Dokument7 SeitenAmendment of Chapter 4-64 of Municipal Code by Adding New Section 4-64-098 Regarding Flavored Tobacco Products and Amending Section 4-64-180Illinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ready For The Snow? Gauging Illinois's Performance On A Critical Core ServiceinalDokument5 SeitenReady For The Snow? Gauging Illinois's Performance On A Critical Core ServiceinalIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cost Shift: Why School Districts Would Benefit From A 401 (K) - Style Retirement PlanDokument24 SeitenThe Cost Shift: Why School Districts Would Benefit From A 401 (K) - Style Retirement PlanIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ForthePeopleFinal-2Getting Less For More: A Report Card On Illinois State Higher EducationDokument66 SeitenForthePeopleFinal-2Getting Less For More: A Report Card On Illinois State Higher EducationIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Tillman's Response To U.S. Sen. Richard DurbinDokument1 SeiteJohn Tillman's Response To U.S. Sen. Richard DurbinIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget Solutions 2014: Pension Reform and Responsible Spending For State and Local GovernmentsDokument29 SeitenBudget Solutions 2014: Pension Reform and Responsible Spending For State and Local GovernmentsIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compass (Summer 2013) Power of School ChoiceDokument28 SeitenCompass (Summer 2013) Power of School ChoiceIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lessons From The Edgar Plan: Why Defined Benefits Can't WorkDokument7 SeitenLessons From The Edgar Plan: Why Defined Benefits Can't WorkIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medicaid SolutionsDokument14 SeitenMedicaid SolutionsIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obstructed Views: Illinois' 102 County Online Transparency AuditDokument21 SeitenObstructed Views: Illinois' 102 County Online Transparency AuditIllinois Policy100% (1)

- Fiscal NotesDokument9 SeitenFiscal NotesIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compass (Spring 2013) Betting On IllinoisDokument28 SeitenCompass (Spring 2013) Betting On IllinoisIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- HB 3411 Makes Illinois' Already-Broken Pension System WorseDokument1 SeiteHB 3411 Makes Illinois' Already-Broken Pension System WorseIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- AFSCME February Bargaining BulletinDokument2 SeitenAFSCME February Bargaining BulletinIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- AFSCME Strike MemoDokument2 SeitenAFSCME Strike MemoIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compass (WINTER 2012) Illinois Labor Law Created Union MonsterDokument28 SeitenCompass (WINTER 2012) Illinois Labor Law Created Union MonsterIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Madigan Letter To Michael Carrigan Regarding Union Pension SummitDokument2 SeitenMadigan Letter To Michael Carrigan Regarding Union Pension SummitIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gov. Quinn State of The State Address 2013Dokument13 SeitenGov. Quinn State of The State Address 2013Illinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Policy Point: Illinois' High-Tax ProblemDokument1 SeitePolicy Point: Illinois' High-Tax ProblemIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key States On The Front Line of Stopping ObamaCareDokument5 SeitenKey States On The Front Line of Stopping ObamaCareIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illinois Is A High-Tax StateDokument6 SeitenIllinois Is A High-Tax StateIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 Illinois Piglet DigitalDokument37 Seiten2012 Illinois Piglet DigitalIllinois PolicyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Municipal Court Lacks Jurisdiction in Cuyos vs Garcia CaseDokument2 SeitenMunicipal Court Lacks Jurisdiction in Cuyos vs Garcia Casekaren igana100% (1)

- LEGRES Case DigestsDokument8 SeitenLEGRES Case DigestsRem SerranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilson V Cook County - Appellate Panel Opinion - Aug 29 2019Dokument17 SeitenWilson V Cook County - Appellate Panel Opinion - Aug 29 2019Jonah MeadowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hayden Town CodeDokument209 SeitenHayden Town CodeFred WisenerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alvarez Press ReleaseDokument1 SeiteAlvarez Press ReleaseFOX 61 WebstaffNoch keine Bewertungen

- EBanking Alert Mobile Application FormDokument2 SeitenEBanking Alert Mobile Application FormKBA AMIR100% (1)

- Court Collection CaseDokument4 SeitenCourt Collection CaseJave Mike AtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alpa V Bhatt - Vs State of Gujarat & 1 - On 7 April 2010Dokument29 SeitenAlpa V Bhatt - Vs State of Gujarat & 1 - On 7 April 2010Kishor NasitNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Juan vs. PeopleDokument16 SeitenSan Juan vs. PeopleMarc Steven VillaceranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Josefa Mercado V Alfredo RizalDokument1 SeiteJosefa Mercado V Alfredo RizalSj EclipseNoch keine Bewertungen

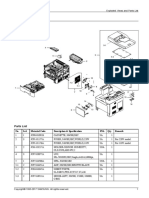

- Main: Exploded ViewDokument30 SeitenMain: Exploded ViewjoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIA, Et Al v. IAC, Et AlDokument3 SeitenNIA, Et Al v. IAC, Et AlTeresita LunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. Santiano (1998)Dokument10 SeitenPeople vs. Santiano (1998)Vince LeidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GSIS v. KapisananDokument2 SeitenGSIS v. KapisananAnonymous XvwKtnSrMR100% (1)

- Risk Attached To PropertyDokument1 SeiteRisk Attached To PropertyanshulNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Power of Attorney Format Indian StyleDokument3 SeitenGeneral Power of Attorney Format Indian StylesriniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Defendant - NYS DivorceDokument2 SeitenAffidavit of Defendant - NYS DivorceLegal ScribdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Property Law ProjectDokument15 SeitenProperty Law ProjectHarsh DixitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alien Registratio ProgramDokument4 SeitenAlien Registratio ProgramAnonymous sAhtoQPrDNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Payton Appellate and Supreme Court Advocacy Fellowship BrochureDokument2 SeitenJohn Payton Appellate and Supreme Court Advocacy Fellowship Brochurecgreene2402Noch keine Bewertungen

- Garcia Vs TolentinoDokument2 SeitenGarcia Vs TolentinoMargarita SisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allotment of Director Identification Number (Din) PDFDokument1 SeiteAllotment of Director Identification Number (Din) PDFAJAY SINGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eric Farrington Government Motion To Revoke Supervised ReleaseDokument4 SeitenEric Farrington Government Motion To Revoke Supervised ReleaseThe Dallas Morning NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principle of Law ContractDokument38 SeitenPrinciple of Law ContractMuhammad ZaimmuddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Supreme Court Upholds Murder Conviction in 1944 Torture CaseDokument2 SeitenPhilippine Supreme Court Upholds Murder Conviction in 1944 Torture Casejharen lladaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chua vs. Court of AppealsDokument18 SeitenChua vs. Court of AppealsCourt JorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- LU V LU YM DigestDokument3 SeitenLU V LU YM DigestjaneliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sales TolentinoDokument344 SeitenSales TolentinokarlshemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vivares Vs STCDokument13 SeitenVivares Vs STCRZ ZamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Universitas Syiah Kuala: Dokumen: Format Kontrak KuliahDokument7 SeitenUniversitas Syiah Kuala: Dokumen: Format Kontrak KuliahRosmiaty SaragihNoch keine Bewertungen