Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Boiling Point On The Border: An Examination of The Sino-Indian Border War of 1962 and Its Implications

Hochgeladen von

PotomacFoundationOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Boiling Point On The Border: An Examination of The Sino-Indian Border War of 1962 and Its Implications

Hochgeladen von

PotomacFoundationCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

B oi l i ng P oi nton t heB or de r :

C a l a n t h i a Me i a n d P a u l N a p o l i t a n o G O V T4 5 1 D r . P h i l i p K a r b e r

A nE x a mi n a t i o no f t h e S i n o I n d i a nB o r d e rWa ro f 1 9 6 2 a n dI t s I mp l i c a t i o n s

De c e mb e r7 , 2 0 1 2

5 AM, October 20, 1962. After years of miscalculations and failure to reach diplomatic agreement, two powers faced off against each other. However, despite the historic crisis occurring across the globe, the two countries discussed here were not the United States and the Soviet Union. The Chinese deployed troops to Thag La Ridge and at this hour launched an attack against Indian posts, beginning the SinoIndian Border War of 1962. These posts were set up as part of Indian Prime Minister Nehrus forward policy, seeking to prevent Chinese advance and push the Chinese out of disputed border areas. After years of miscalculations, increased tension due to revolution in neighboring Tibet, and ultimately an inability to reach agreement peacefully, China launched simultaneous attacks beginning at 5 AM on October 20, 1962, resulting in a quick and decisive Chinese victory, with important implications for both sides in the wars aftermath. The war of 1962 with India was long Chinas forgotten war. While extensive literature has explored the border conflict from an Indian perspective and analyzed Indias China War in great detail, little was published regarding the Chinese perspective.1 Delving into various sources from both Indian and Chinese aspects, this paper analyzes the 1962 Sino-Indian War with coverage on historical background, confrontational claims, campaign process and the implications for both sides of the campaign.

Background

In order to fully understand the background of the 1962 Sino-Indian Border War, one must probe into the historical and geographical elements that shaped the relations between the two countries. Conventionally, the discussions on the SinoIndian border issue have conveniently divided the frontier into the western, middle,

1

Indias China War, written by Neville Maxwell, is the first and one of the most important detailed accounts of the events surrounding the Sino-Indian War of 1962. Interestingly, as the awareness of the 1962 war arises in China, Maxwell recently published an article titled Chinas India War in answering the question how the Chinese saw the conflict.

and eastern sectors. In this section, we will provide detailed historical background with respect to each sector. Map 1: The Middle Sector2

Aksai Chin, Tawang, and India in 1961-1962 [map], in Steven A. Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1990, p. 10.

The middle sector, illustrated by Map 1, runs from the northwestern tip of the Punjab to Nepal. This sector has seen relatively less conflicts. Although the Indian government claimed sovereignty of the western end of the middle sector based on the treaties of 1684 and 1842, the middle sector has never been subject to any treaty or agreement concluded between British India or the states of India, Tibet, or China. The western sector, particularly the highly disputed Aksai Chin area, was not blessed by the absence of conflict. As Map 2 shows, the western sector, running from Afghanistan to the northwestern tip of the Punjab, separated Kashmir from Xinjiang and the western extremity of Tibet. The Indian and Chinese governments draw drastically different borderlines in Aksai Chin, an area that expands from Karakoram Pass in the west to Kongka Pass in the east, covering the area between Xinjiang and Kashmir. The Chinese government claims that the line of occupation, illustrated in the map in dotted lines, runs more or less straight from the Karakoram Range east along the crest of the Karakoram Range to the Kongka Pass.3 However, the Indian government claims that from the Karakoram Pass the frontier executes a deep salient up to a point on the crest of the Kunlun Range and descends again to the Karakoram Range at a point east of the Kongka Pass.4 The British Indian government acted as if Aksai Chin were part of Ladakh, within its jurisdiction. Yet the Chinese conversely claim Aksai Chin as part of Xinjiang. Until the 1950s, the frontier was delimited in this area and there was something of a void between the Indian administration in Ladakh and Chinese administration in Xinjiang.

J. M. Addis Papers, The India-China Border Question, (Cambridge, Mass: Center of International Affairs, Harvard University, April 1963) http://chinaindiaborderdispute.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/india-chinaborder2.pdf, p.7. 4 Ibid., p.13.

Map 2: The Western Sector5

The eastern sector, as indicated by Map 3, refers to the Sino-Indian border from Bhutan in the west to Burma in the east, where 99,000 square kilometers of territory is in dispute, described by the Indians as the Northeast Frontier Agency

5

Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis, op cit., p. 11.

(NEFA).6 Based on historical treaties and documents of the British administration, the Indian government claimed sovereignty over the eastern sector. At the same time, the Indians solicited moral and spiritual support based on the essential and eternal Indianness of this part of the frontier. A production of the Simla Conference, the McMahon Line is the most important historical factor in this area. In 1914, the British government convened the Simla Conference, which was presented as an attempt to coordinate relations between China and Tibet. However, according to Maxwells Indias China War, the aim of the British was that Tibet, while nominally retaining her position as an autonomous state under the suzerainty of China, should in reality be placed in a position of absolute dependence on the Indian government.7 The main British effort at the conference primarily focused on dividing Tibet into two zones: inner and outer Tibet. Although Chinese suzerainty over the entire region was to be recognized, as officially noted by the British government, under such a treaty, China had no administrative rights in the outer Tibet area, thus keeping China back from the Sino-Indian borderline. Such an effort was strongly resisted by Beijing; from the Chinese perspective, the British simply wanted to separate a great part of Tibet from China. Yet British Representative McMahon proceeded to sign a joint declaration with the Tibetan delegation without the official consent from Beijing. This secret byproduct of the Simla Conference was consolidated in the 1914 discussions between the British and Tibetans, which thereafter led to an alignment with only bilateral recognition the McMahon Line. On the Chinese side, Beijings leaders constantly resisted the secret British-Tibetan declaration and the McMahon Lin, recognizing it as a manifestation of the British imperialist endeavors. Essentially, what McMahon alignment did was to push the Sino-Indian boundary northward for approximately 60 miles, which indicated

Gregory Clark, In Fear of China, Lansdowne Press, 1967, http://gregoryclark.net/China/ [accessed 10 November, 2012]. 7 Neville Maxwell, Indias China War, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1970), p. 46.

British intention to create a tribal no-mans-land under nominal British sovereignty.8 Map 3: The Eastern Sector9

The late 1940s witnessed the grand power transition in Asia and thereafter the emergency of an independent India and a Communist China. The newly established Sino-Indian relations experienced a smooth startin actuality, independent India was the first state outside the Soviet bloc to recognize the new China during the last days of 1949. As Maxwell suggested, Friendship with China had been the keystone of the foreign policy Jawaharlal Nehru had set for India: non-alignment, the refusal of India to throw in her lot with either of the blocks, Communist and anti-Communist, into which the world

8 9

Ibid., p. 51. Hoffmann, India and the China Crisis, op cit., p. 17.

seemed then so neatly divided; self-reliance in defense, independence in foreign policy; concentration upon economic development, at the risk of allowing the armed forces to run downall of these depended upon friendship with China, and a peaceful northern border. Hostility with China, a live border in the north demanding huge defense outlaysthese would bring down the whole arch of Nehrus policies.10 Given the presumption that both countries needed peace for their reconstruction and development, the Sino-Indian treaty of 1954 stated in its preamble that the two governments agreed upon the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, in which a commitment to mutual respect, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference, mutual benefit and peaceful co-existence was stated.11 Such was the hope that if these principles were applied not only between various countries but also in international relations generally, they would have formed a solid foundation for the conception of collective peace. Also, nonalignment, the defining feature of Indian foreign policy since independence, has always been a guiding principle respected and followed by New Delhis decision makers and political elites. Nonalignment was announced by Nehru, who believed that the only way for India to pursue its goals internationally was keeping a far distance from any formal alliance, especially from the Moscow and Washington-led blocs of nations. Nonalignment also reflects Gandhis nonviolence principles in resolving international disputes, calling for cooperation and peaceful dialogues. Nehrus advocacy for such principles bolstered Indias reputation as a leader in the global decolonization movement, in which newly independent states struggle with ensuring the room for survival amidst superpower rivalries and lingering colonial influence. However, under the surfaces of peaceful coexistence and non-alignment hid a few turmoil elements. The issue of the McMahon Line, seen by the Chinese as

10 11

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 11. Agreement on trade and intercourse between Tibet region of China and India, (New York, NY: Secretariat of the United Nations, Vol. 299, Nos. 4303-4325); http://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/unts/volume%20299/v299.pdf [accessed 20 October 2012].

British imperialist hangover in India after independence, has affected Sino-Indian relations from 1914 until present. The government of the Peoples Republic of China today, like its predecessors during the Kuomintang era, does not consider that China has any obligation from the secret British-Tibetan declaration of the Simla Conference and related discussions in 1914. When the British relinquished their control over the Indian empire in 1947, the last legacy they left to Indians leaders was to translate the McMahon Line from the maps to the ground, as the effective northeast boundary of India by establishing posts over the tribal territory. The new Indian government guaranteed the receding British colonists that New Delhi would complete the unfinished work in the tribal belt: if anything, they intended to pursue an even more forward policy than had the British.12 The hope for collective peace was first shattered by Chinese annexation of Tibet in 1951.13 In October 1950, the Peoples Liberation Army conducted military actions in the Tibetan area of Chamdo. In 1951, a Seventeen Point Agreement was signed between Beijing and the Tibetan representatives, headed by Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, which affirmed Chinas sovereignty over Tibet.14 The Chinese occupation of Tibet altered the power dynamics among China, Tibet, and India, under which Tibet historically served as a buffer zone between China and India. This was a turning point in the Sino-Indian border issue. As Nehru later stated in the Lok Sabha on February 23, 1961, When the Chinese forces entered Tibet in 1950-1951, we thought that the whole nature of our border had changed. It was a dead border, it was now becoming alive, and we began to think in terms of the protection of that border.15 In actual policy terms, such a turning point meant an increase in the number of checkpoints and patrols along the borderlines. During this period, the Indians were moving to fill the void in the eastern sector of the Sino-

12 13

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 61. Peaceful liberation in Chinese official language . 14 Shanti Prasad Varma, Struggle for the Himalayas, (Mori Gate, India: University Publishers, 1966), p.73. 15 Addis, The India-China Border Question, op cit., p.46.

Indian borderline, while the PLA carried out extensive activities in the western sector, particularly in the highly disputed Aksai Chin area. The real borderline skirmish started in 1954, marked by the Barahoti Conference. Although through later-on negotiations this small disputed area had been successfully neutralized militarily, Chinese and Indian civilian officers were camping in it side by side.16 In 1957, the Chinese had completed the construction of the Xinjiang-Tibet motor road, which went through the Aksai Chin area. This move was perceived by the Nehru administration as a surprising aggression, as Beijing did not inform nor seek permission from the Indian government, who viewed Aksai Chin as indisputably part of Indian territory. During the 1958-1959 period, the Chinese government furthered their occupation of the Aksai Chin area and their claim to NEFA in the eastern sector. In March 1959, the armed rebellion in Tibet was seen by Beijing as a humiliation to China and a conspiracy supported by the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States, the Indian Government, and the Nationalist Government. Following the uprising, both sides began advancing further into the frontier areas, altering the status quo of administrative void, and resulting in the first exchange of fire between Chinese and Indian patrols. The incident also accumulated Nehrus unremitting pressure from the press and from the opposition in parliament to take a strong position. The honeymoon between Beijing and Delhi hence came to an end. In August 1959, an Indian border guard was killed during an armed clash at a point called Longyu on the McMahon Line. As Nehru revealed on November 16, 1959, after the Longyu incident it has been decided to place the entire frontier of India in direct charge of our army.17 The more serious clash in October 1959 at the Kongka Pass on the Kashmir/Xinjiang border, with casualties on both sides, galvanized the Indian public opinion and triggered alarmed attention among the

16 17

Ibid., p. 50. Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p.73.

10

Chinese leadership and the Indian government. Facing heightened tension, Beijing called for China and India to each withdraw 20 kilometers at once from the McMahon Line in the east and from the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the west. However, despite such a proposal, as well as prime ministers meeting between Zhou Enlai and Nehru, China and India failed to reach an agreement.18 While China constantly restated their claim that the entire Sino-Indian boundary had never been delimited, India refuted such understanding and defined it as wholly incorrect and unacceptable. The early 1962 witnessed a series of fortified defense, exchanges of diplomatic notes, and the Dhola Post crisis. On October 6, the border conflict reached its climax when Beijing proclaimed that India has finally categorically shut the door to negotiations in their reply to the October 6 Indian notes. The belligerent intentions and active preparations for military actions from both sides therefore led to the inception of the Sino-Indian War on October 20, 1962. In addition to bilateral factors, the international political context at the time, especially the role of the United States and the Soviet Union, also helped precipitate the Sino-Indian conflicts. Throughout the 1959-1962 period, international public sympathy usually side with India, as India charged that it was China that refused to negotiate border disputes and embarked on an aggressive expansion to Indian territory. Following Beijings logic, India was the embodiment of capitalism and imperialism hangover, leaning toward the United States. During those years, the United States clearly changed its policy toward the Nehru regime. According to the Chinese Communist Partys Sino-Indian War propaganda documentary, the United States almost doubled its foreign assistance to India, amounting to $4.1 billion during the two years of Indian confrontation with China.19 In addition, the Soviet Union was also an actor whose role cannot be underestimated. It was exactly during the Longju incident when Khrushchev was preparing for his visit with President

19

Sino-Indian War, http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XNjY0NDE5OTI=.html [accessed 25 October 2012].

11

Eisenhower as an effort to amend relations with the United States and regenerate the Spirit of Camp David. As J.M. Addis The India-China Border Question records, an editorial in Peoples Daily of February 27, 1963, entitled Whence the differences? a reply to Comrade Thorez and other comrades, claimed: On that day a socialist country, turning a deaf ear to Chinas repeated explanations of the true situation and to Chinas advice, hastily issued a statement on a Sino-Indian border incident through its official news agency. Making no distinction between right and wrong, the statement expressed regret over the border clash and in reality condemned Chinas correct stand.20 At the dawn of the Sino-Indian War, Khrushchev showed willingness to amend relations with the United States, which has always acted as a strategic ally with India. All these factors contributed to the acceleration of Sino-Indian border conflicts, which eventually triggered in war in October 1962.

Timeline 1: From Applying the Forward Policy to Ceasefire21: 1961 - Nehru sends troops and border patrols into disputed frontier areas to establish outposts; skirmishes increased in late 1961 Dec. 1962 - India invades and takes Portuguese Goa July - Skirmishes in Aksai Chin 4 Aug. - China accuses India of advancing even north of the McMahon Line Aug. - Chinese logistic and manpower buildup along the frontier Sep. - Isolated skirmishes along the disputed border 5 Oct. - India forms special Border Command under General Kaul

[Whence the differencea reply to Comrade Thorez and other comrades], [Peoples Daily], (27 February 1963), citied in J. M. Addis Papers, The India-China Border Question, p.174. 21 Appendix 1 Chronology of Events from U.S. Naval Lieutenant Calvin James Barnards The China-India Border War CSC 1984 accessed http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/CJB.htm .

20

12

10 Oct. - First heavy fighting, at Tseng-Jong in NEFA 20 Oct. - Chinese launch a massive assault across the Namka Chu River in NEFA 20-21 Oct. - Chinese launch simultaneous attacks in Aksai Chin, successful against Galwan Valley and Chip Chap Valley posts 23 Oct. - Chinese overrun all posts down to Tawang in NEFA 24-25 Oct. - Chinese probing attacks at Walong, in eastern NEFA Late Oct. - Lull in fighting; unproductive diplomatic efforts at compromise fail; numerous changes in command in NEFA Indian units 14 Nov. - Nehru's birthday - Indians launch an attack on Chinese north of Walong 15 Nov. - the Indian offensive fails 16 Nov. - Chinese troops overrun Walong 17 Nov. - Chinese attack Indians on Bailey Trail in NEFA; a Chinese attack at Se La, NEFA, is repulsed; Chinese begin a simultaneous attack on Chushul in Aksai Chin 18 Nov. - Chinese successful at Chushul; no Indian force remains in Aksai Chin; Indian forces are forced to withdraw from Se La; Chinese forces attack Bomdi La 19 Nov. - Chinese attack Chaku, last Indian forces in NEFA, successfully; Chou En-Lai gives ceasefire dictum to Indian official in Peking 20 Nov. - Chou publicly announces ceasefire; India requesting U. S. military aid, but ceasefire ends need for U. S. intervention 21 Nov. - Ceasefire goes into effect 1 Dec. - both sides' troops withdraw 20 kilometers from new boundary lines; repatriation of prisoners starts

13

Indian Objectives/Confrontational Claims

Pursuing the Forward Policy New Delhi must assert its rights by dispatching properly equipped patrols into the areas currently occupied by the Chinese, since any prolonged failure to do so will imply a tacit acceptance of Chinese occupation, and a surrender to Pekings threat to cross the McMahon Line in force should Indian patrols penetrate into the disputed areas of Ladakh.22 This quote from an editorial in the Times of India in October 1959 expressed a conclusion that the Indian government also reached in 1960 in developing a policy to deal with Chinese border disputes.23 Indian objectives and confrontational claims leading up to the 1962 Sino-Indian Border War found their expression in the Indian forward policy. The Chinese construction of a road through Aksai Chin in 1956, linking Xinjiang and Tibet, raised issue for the Indian government, which maintained that India possessed sovereignty over Aksai Chin. Regarding the McMahon Line in the eastern sector, Prime Minister Nehru presumed that China recognized its legitimacy, as no border questions were raised when the Sino-Indian Agreement on Tibet was concluded in 1954.24 However, in one of the notes exchanged between Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai and Indian Prime Minister Nehru, Chou En-Lai stressed that the McMahon Line was a product of the British policy of aggression. Juridically it had no legal basis.25 Nehru responded with his assertion that the McMahon Line had a natural, geographical basis. According to Nehru, It also coincided with tradition and over a large part was confirmed by international treaties.26 The Indian government was committed to getting China out of Aksai Chin and maintaining the McMahon Line, preventing the threat of a Chinese advance across the line. Proposals put forward by both Chou En-Lai and

22 23

Maxwell, Indias China War, pp.173-174. Ibid., pp. 173-174. 24 T. Karki Hussain, Sino-Indian Conflict and International Politics in the Indian Sub-Continent, 1962-66, (Faridabad: Thomson Press (India) Limited, 1977), p. 8. 25 Ibid., p. 9. 26 Ibid., p. 9.

14

Nehru regarding different means of withdraw were not found acceptable by the other side, and Chou En-Lais visit to New Delhi in April 1960 was considered a total failure.27 Around the time of Chou En-Lais visit, a quid-pro-quo settlement, such as the Chinese recognizing the McMahon Line in lieu of Indian recognition of Aksai Chin as a Chinese position seemed possible.28 According to Indian Defence Minister Krishna Menon, aroused public opinion and the influence of the Home Minister, Pandit Pant played a strong role in the Indian resistance of such negotiations.29 When diplomatic measures were unsuccessful in settling boundary disputes between the Chinese and Indians, the Indian government determined it needed to pursue other measures to settle the argument and achieve a boundary resolution congruent with Indian interests. China committed to maintaining its presence in the area and refused to withdraw, which meant India faced alternative policy choices: to attempt to push back Chinese presence through the use of military force, to accept the Chinese status quo on the boundaries, or to pursue a third option. Eager to avoid war and not willing to accept Chinese terms, the Indians pursued the third choice, which became known as the forward policy.30 The forward policy emerged in 1960 under Prime Minister Nehrus government, though it was not really put into effect until the end of 1961, largely owing to the Armys unwillingness to undertake a course for which the military means were wholly lacking.31 The forward policys first objective was to prevent any further Chinese advance. The policy sought to establish an Indian presence in Aksai Chin to

27

The China-India Border War of 1962, (report prepared by Lieutenant Commander James Barnard Calvin, U.S. Navy; Marine Corps Command and Staff College, April 1984); http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1984/CJB.htm (accessed, 27 September 2012), Chapter II. 28 Hussain, Sino-Indian Conflict and International Politics in the Indian Sub-Continent, 1962-66, op. cit. p. 15. 29 Ibid., p. 15. 30 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 174. 31 Ibid., p. 199.

15

encourage the Nehru proposed joint withdrawal, which clearly aligned with Indian intentions to eventually get the Chinese out of the area.32 The forward policy sought to undermine Chinese control of the disputed areas by the interposition of Indian posts and patrols between Chinese positions, thus cutting their supply lines and ultimately forcing them to withdraw.33 Nehru sent Indian troops into Aksai Chin, and India established about forty-three outposts in the western sector by the end of 1961. Nehrus forward policy was formulated under the assumption that the Chinese would not respond with war. The Chinese began sending a series of angry protests in August 1961, repeatedly warning to retaliate across the McMahon Line if the Indians continued pressing forward.34 Still, the premise of the forward policy held that no matter how many posts and patrols India sent into Chinese claimed and occupied territory the Chinese would not physically interfere with them provided only that the Indians did not attack any Chinese positions.35 Nehru dismissed the Chinese warnings, explaining to Parliament that the Chinese had become rather annoyed because Indian posts had been set up behind their own, and reassured any members who might have thought the Chinese tone dangerous.36 Nehru continued, If they do take those steps we shall be ready for them.37 As can be seen in Map 4, Indias forward policy movements pushed into Chinese claimed Aksai Chin territory, leading to skirmishes. As the timeline details, the Chinese also accused India of advancing even north of the McMahon Line in August 1962. After the Indian forward policy became effective in 1961, skirmishes increased over the next several months, ultimately leading up to the beginning of the large-scale military campaign in October 1962.

32 33

Ibid., p. 174. Ibid., p. 174. 34 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter II. 35 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 175. 36 Ibid., p. 235. 37 Ibid., p. 235.

16

Map 438:

38

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 257.

17

Chinese Objectives/Confrontational Claims Mr. Nehru is the premier of India, our friendly neighbor, and one of the most influential politicians in the world whom we respect. To us, we should not forget that he is a friend of China who opposes the imperialists policies of war and aggression. In addition, he has made many open-minded comments with regards to social progress. However, what a different tone he was singing in his speech on April 27th, 1959!39 Headed by Nehru, the Indian ruling group has interfered in our Tibetan affairs over and over again, holding expansionist ambitions toward Tibet which has exposed their devious nationalist policy. Yet after the failure of the Tibetan rebellion he instigated, Nehru has again betrayed us, turning against China with notoriously mad attacks.40 The first paragraph is quoted from the Peoples Dailys coverage on the Lhasa Rebellion on May 6, 1959. The second statement was written few days before the launch of 1962 Sino-Indian War. This section seeks to offer an explanation for the shift in Chinas attitude toward India from our friendly neighbor to the mad attacker, examining factors that led China to war with India in 1962. This section analyzes both bilateral and international perspectives, emphasizing the Tibet issue and chronological border conflicts. From a domestic perspective, the Tibet issue and a series of Sino-Indian border conflicts from 1959-1962 were of critical importance. On the subject of Tibet, John W. Garver argued that a starting point for understanding the Chinese belief system about the 1962 war is recognition that the road to the 1962 war begins in Tibet.41 In other words, according to Garver, Tibet was the root cause of the 1962 war from the Chinese perspective. After a series of interwoven exchanges between India and

39

[The Tibetan Revolution and the Philosophy of Nehru], [Peoples Daily], (6 May 1959), http://www.tibetology.ac.cn/zh/component/content/article/253--1/44172010-03-23-14-14-18?view=article&id=4417%3A2010-03-23-14-14-18&catid=253%3A-1. 40 [Reanalyze Nehrus Philosophy regarding the Sino-Indian border issue], [Peoples Daily], (October 1962), http://rmrbw.net/simple/index.php?t298195.html, p.2. 41 John W. Garver, Chinas Decision for War with India in 1962, http://chinaindiaborderdispute.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/garver.pdf[accessed 1 November 2012], p.6.

18

Tibet, Chinese leaders felt compelled to punish India, ending Indias endeavors to restore the pre-1949 status quo ante in Tibet, therefore undermining Chinese control of the region. Chinese leaders insisted that the Nehru administration saw seizing Tibet and potentially turning Tibet into an Indian protectorate as a crucial strategic move in Indias forward policy. The Tibet issue deeply casted Chinese deliberations with regards to Indias aggression along the Sino-Indian border. The most symbolic event in this argument was Indias support of the Dalai Lama and Tibetan refugees after the 1959 Tibet Uprising, a move seen by Chinese leaders as interference in domestic affairs.42 Indeed, Mao Zedong ordered the initiation of a series of polemics in the two major official news outlets of the Communist Party, Peoples Daily (renmin ribao), and Xinhua News Agency (xinhua she). The first quote presented in the beginning of this section was from a famous piece titled, The Tibetan Revolution and the Philosophy of Nehru, published on Peoples Daily at Maos instructions. On a different front, the Sino-Indian border issue was a direct fuse for the 1962 war. Although the international community widely blamed China for instigating the conflict, from a Chinese perspective, such accusations lack knowledge of Indias aggression along the borderlines. The first inkling of troubles was an armed clash in Longju on the McMahon Line in August 1959, in which an Indian border guard was killed.43 The Longju incident triggered an outburst of international condemnation against China. The international community accused China of aggression, an extreme and loaded term in diplomatic parlance. As Zhou Enlai complained in a meeting with Nikita Khrushchev, what are we supposed to do if they attacked us first? We cannot just fire in the air. The Indians even crossed the McMahon line. Besides, we are undertaking measures to resolve the issues peacefully by

42

1962 [The 1962 Sino-Indian War: Cause and Course], [china.com.cn], (23 Dec 2008), http://www.china.com.cn/fangtan/zhuanti/200812/23/content_16993225.html [accessed 15 October 2012]. 43 Addis, The China-Indian Border Issue, op cit., p. 69.

19

negotiation.44 Mao thereafter reiterated Zhous prediction, underlining that the border issue with India will be decided through negotiations.45 Such a promise could be exemplified by Maos order in November 1959, under which he withdrew Chinese guards 20 kilometers along all the borders with a request for Indias reciprocation. However, although Chinese leaders had shown sufficient willingness to concede, Nehru rejected the swap proposal and insisted China make further concessions such as the abandonment of Aksai Chin. In the following years, India continued with its assertive and unyielding approach in the border dispute, and strengthened its aggression in the western border sector, which eventually led Mao to reverse his decision.46 Chinas willingness to negotiate with India can also be observed in the case of the 1960 talks. In order to seek a peaceful resolution of the Sino-Indian border disputes, Premier Zhou Enlai visited New Delhi in April 1960 and met with Nehru. However, the meeting did not yield any constructive outcomes, as Zhou Enlais goodwill and Chinas unilateral decision to halt border patrols were perceived as a sign of weakness by the Indian government.47 As a result, upon conclusion of the meetings, Indian forces continued to challenge China and progressed beyond the Line of Actual Control first in the western sector, establishing 43 strongholds within Chinese territory, then in the eastern sector, crossing the McMahon Line. Unfortunately, Nehrus confidence that

44 45

Ibid., p. 70. Ibid., p.71. 46 Four days after the border conflicts broke out, on October 24th, 1962, China has released a statement calling for a seize fire and reopening of peace talks. On November 4th, Zhou Enlai again reached out to Nehru, hoping to bring India back to the negotiation table. On November 15th, Zhou Enlai wrote to leaders of Afro-Asian countries as an effort to express Chinas positions in the conflict and to encourage AfroAsian leaders to facilitate a peaceful resolution of the border disputes. However, all these efforts were met with refusal from Nehru, including in the aforementioned two cases, which led Chinese leaders to proclaim people of the world will see clearly who is peace-loving and who is bellicose; who upholds the friendship between the peoples of China and India and maintains Afro-Asian solidarity, and who destroys them; who defends the common interest of Afro-Asian nations in their struggle against imperialism and colonialism, and who is against such common interest. 47 Yang Zhifang, [Mao Zedong wanted to divert the attention of the Chinese public on domestic issues by launching attacks on India], [ifeng.com], (26 October 2012), http://news.ifeng.com/history/zhongguoxiandaishi/special/qlzyzz/#pageTop [accessed 1 November 2012].

20

the Chinese were just bluffing and would never dare to attack India led to the end of Maos armed coexistence and Chinas military actions in 1962.48 The Tibet issue, the border disputes, along with bilateral and international pressure given by both the West and the Soviet Union, pushed China to the brink of the 1962 war. From the Chinese perspective, it was precisely the following perceived motives of India that led to Chinas decision to go to war with India. First, Nehru revealed in the book The Discovery of India his ambitions for building an Indian empire that expanded from the Middle East to Southeast Asia, even before Indias independence eighteen years prior.49 After independence, Nehru and his ruling group started to pursue expansionist policies, seeking control of neighboring nations economy and trade through intervention in their domestic and foreign policies.50 Under such expansionist ambitions, the ruling group of India judged Tibet as within its sphere of influence. Second, China believed, without doubt, the United States provided support to the Nehru government as an effort to contain China. The Kennedy administration openly supported Indias continued aggression along the Chinese borders by encouraging Nehru to refuse negotiations and providing economic and military aid to help Nehru strengthen his forces.51 China viewed these observations as proof that the United States and India formed a de facto alliance. From the Chinese perspective, Indias expansionist ambitions and Chinas conspiracy regarding the imperialist powers made the 1962 Sino-Indian War necessary and unavoidable.

48 49

Addis, The China-Indian Border Issue, op cit., p. 70. [Reanalyze Nehrus Philosophy regarding the Sino-Indian border issue], op cit., p.1. 50 Ibid., p.3. 51 [The Shadow of the U.S. in the Sino-Indian War: the U.S. instigation of India], [Sohu Military], (8 October 2012), http://mil.sohu.com/20121008/n354443488.shtml[accessed on 10 November 2012].

21

The Campaign

Start

Successful Chinese simultaneous attacks in the east and west

Diplomatic measures fail, changes in Indian Middle command/strategy, seek aid End All-out attack by Chinese, ceasefire

The Chinese deployed for their assault at Thag La Ridge, along the McMahon Line in the eastern sector, on the night of October 19. They were very confident in their forces, and convinced that Indians would not open fire, even lighting fires along the way to keep warm. At 5 AM on October 20, 1962, the Chinese attacked Indian outposts on the Thag La ridge.52 Retired Indian Brigadier J.P. Dalvi, who fought during the war and was present at the Thag La ridge confrontation, recalled that the Chinese opposite Bridge III fired two Verey lights. The signal was followed by a cannonade of over 150 guns and heavy mortars, exposed on the forward slopes of Thag La. Our positions came in for a heavy bombardment.53 For Brigadier Dalvi, who spent several months as a prisoner to the Chinese, This was the moment of truth. Thag La Ridge was no longer, at the moment, a piece of ground. It was the crucible to test, weigh, and purify Indias foreign and defence policies. As the first salvoes crashed overhead there were a few minutes of petrifying shock. The contrast with the tranquility that had obtained hitherto made it doubly impressive. The proximity of the two forces made it seem like an act of treachery. It had started. This was the end of years of miscalculations; months of suspense; days of hope and the end of a confused, nightmare week.54

52 53

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 357. J.P. Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder: The Curtain-Raiser to the Sino-Indian War of 1962, (Bombay: Thacker, 1969), p. 364. 54 Ibid., p. 364.

22

This assault marked the start of the Sino-Indian Border War, an eye-opening and humiliating conflict for the Indians. The Chinese attacked central Indian positions. The Gorkhas and Rajputs bore the brunt of the assault, with Chinese artillery striking many Gorkhas as they tried to move positions and the Rajputs facing simultaneous attacks from two sides.55 The Indians, outnumbered and under armed, attempted to valiantly fight back. Nonetheless, the Chinese strength proved too much to handle. The Chinese then began their assault on Tsangdhar. The Gorkhas and Rajputs along the river line fell within four hours, by 9 AM, and the vital position at Tsangdhar by this point was defended only by a weak company of Gorkhas which had been preparing to march out to Tsangle and the two paratroop guns. Firing over open sights, these fought until the crews were wiped out.56 The Chinese began their first attack on Tsangdhar at 9 AM that same day. Transport aircraft attempted to execute drops as usual but were quickly shooed-off by Chinese fire.57 Dalvi expressed his ashamedness with Indian forces and highlevel command, writing, No one had bothered to tell the Air Force that a battle was imminent or had in fact started. We did not believe in unity of command and obviously Army-Air cooperation was not functioning smoothly.58 Dalvi decided to move with the remaining Gorkhas to Tsangdhar to regroup there. He received approval from General Prasad for his move to Tsangdhar. Dalvi quoted Prasads official report, Prasad stated, Brigadier Dalvi asked my permission to withdraw to Tsangdhar and reorganize there. He moved only on my direct orders, but before he could get to Tsangdhar the enemy had already occupied this feature.59 The Chinese take-over at Tsangdhar, according to Dalvi, marked the tragic end to a week which had begun with Nehrus Olympian edict to throw out the Chinese and had finished

55 56

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 357. Ibid., p. 357. 57 Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder, op cit., p. 373. 58 Ibid., p. 373. 59 Ibid., p. 375.

23

with the complete rout of the out-numbered and out-weaponed troops.60 Dalvi criticized the Nehru administration, though unwilling to give an inch, India instead lost thousands of square miles. Bleeding from a thousand wounds, 7 Brigade expired: but India was to go on bleeding for many more years.61 Dalvi praised the valiant fight of Indian soldiers, but ultimately, undermanned, out-weaponed, and under trained, the Indian were doomed to fail when the Chinese launched their offensive at Thag La Ridge. Map 5 shows initial Chinese attacks launched against Indian posts in the eastern sector. Map 562:

60 61

Ibid., p. 375. Ibid., p. 375. 62 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 361 .

24

The Chinese simultaneously attacked the western sector. In the west, Chinese attacked the Indian posts in the Chip Chap, Galwan, and Pangang Tso areas.63 In addition to the aforementioned eastern sector assault, Wave after wave of Chinese troops in a massive two pronged sweep came close to encircling the 50,000 square miles of Indian, Himalayan territory.64 The Chinese shelled and overran the main Indian Galwan post. Neville Maxwell explained that the posts fought as best they could but were soon overwhelmed, the little garrisons being either killed or captured.65 Western Command gave orders to the small and isolated posts to withdraw before the Chinese offenses reached them.66 The forward policy had met with the fate which from the beginning the real soldiers, like Dalvi, had foreseen.67 The delusion, and stubbornness in both underestimating Chinese warnings and pursuing a forward policy that the Indians were not militarily capable of pursuing, resulted in the destruction of Indian posts, loss of lives, and withdraw a humiliating period for the Indians after initial Chinese assaults in the Sino-Indian Border War. After withdraw became imminent for certain NEFA and western posts, Indian leadership needed to construct retreat plans and decide where to make a stand. In the east, immediately Indian generals, General Thapar and General Sen, felt compelled to make a stand at Tawang. After the Thag La Ridge victory, the Chinese immediately developed a three-prong attack. The first Chinese force was the one that had captured Dalvi and defeated 7 Brigade and had come through Shakti and was poised ten miles north of Tawang.68 The second prong came through Khinzemane and joined with the first force.69 The Chinese also sent a third line of

63

M.L. Sali, India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector, (New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation, 1998), p. 88. 64 Ibid., p. 88. 65 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., pp. 358-359. 66 Ibid., p. 359. 67 Ibid., p. 359. 68 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. 69 Ibid., Chapter V.

25

advance that came down through Bum La.70 Thus, by October 23, Tawang was threatened from both the north and the south. With no natural defences at Tawang, consequently on that same day orders went out to the force at Tawang that they were to withdraw to Bomdi La, some sixty miles back on the road to the plains.71 The attractiveness of Bomdi La lied in the calculations that it marked the farthest point to the north where the Indians could build up more quickly than the Chinese.72 At Army Headquarters, conversely, Brigadier Palit urged that India should hold Se La much closer to Tawang only about fifteen miles away. Palit argued for a hold at Se La because of its natural defensive value in denying invaders access to the plains, and ultimately General Sen reversed the order to hold Se La instead of Bomdi La. The Indians withdrew to Se La, which they planned to reinforce and defend in strength.73 However, there were several difficulties in the plan to defend Se La, which proved disastrous for the Indians. The height at Se La required troops to operate at altitudes between 14,000 and 16,000 feet, which they were not capable due to lack of proper equipment and not being acclimated after coming from the plains.74 The defensive position at Se La was also too far from the plains to quickly build up and too near to Tawang that the Chinese could more easily assault the post. Committing to Se La meant the Indians needed to hold a very deep area, from Se La to Bomdi La, separated by some sixty miles of difficult and unreliable road through high, broken country.75 Air support was only on a supply level; the government did not want to risk tactical air support with bombers or ground-attack aircraft for fear of Chinese retaliation against Indian cities, especially Calcutta, particularly with memory of the huge panic that

70 71

Ibid., Chapter V. Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 368. 72 Ibid., p. 368. 73 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. 74 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 369. 75 Ibid., p. 369.

26

swept Calcutta during World War II when random Japanese bombs fell there.76 In addition to occupying Tawang on October 25, the Chinese also attacked Indian posts elsewhere along the McMahon Line and these had fallen under varying degrees of pressure.77 In the eastern sector, the Chinese also made some probing attacks on Walong on October 24 and October 25, but after October 25, NEFA fell into a lull, with the majority of Chinese forces paused in Tawang, about ten miles south of McMahon Line.78 Changes of the Indian command of eastern brigades transpired until no brigade in NEFA had its original battalions under command.79 Conversely, the Indians made focused defensive efforts in the western sector, pulling troops out of Kashmir and also deploying all the Western Commands transport reserves to the job of reinforcing the Ladakh front, and the Indian strength there grew quickly.80 The Indians established divisional H.Q. at Leh in early November, with an additional four infantry battalions and a fifth battalion added by mid-November.81 Though a two-week lull in military conflict emerged after the initial period of the war, diplomatic activity increased. Chinese Premier Chou En-Lai sent a letter on October 24, 1962, to Prime Minister Nehru offering a peace settlement that proposed disengagement of both sides and withdraw twenty kilometers from present lines of actual control, a Chinese withdrawal north in NEFA, and that China and India not cross lines of control in Aksai Chin.82 Chou En-Lai offered that the Chinese would pull back over the McMahon Line, and Indian troops in the remaining forward posts in the western sector would withdraw to the line that the Indian Army had held before the forward policy was put into effect in 1961.83

76 77

Ibid., p. 370. Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. 78 Ibid., Chapter V. 79 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 371. 80 Ibid., pp. 370-371. 81 Ibid., p. 371. 82 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. 83 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 374.

27

Nehru replied on October 27 with eagerness to restore peace and friendly relations, for which he was criticized for being mild despite Chinese aggression.84 Nehru disagreed with a mutual twenty kilometer withdrawal after 40 or 60 kilometers of blatant military aggression. Nehru proposed, instead, a return to the boundary prior to 8 September 1962 before any Chinese attacks; only then would India be interested in talks.85 After another exchange of the letters, Chou En-Lai reinforced the proposal to return back to the Line of Actual Control, and Nehru changed tone and showed that New Delhis approach to the boundary dispute had changed only to harden.86 Ultimately, the Indians were not willing to budge on their claimed lines, and a failure to reach agreement despite Chinese initial victories forced them to reconsider foreign involvement. As the campaign progressed, initial Indian defeats and the appearance of a lengthy war forced Nehru to budge on his non-alignment policy. He finally shifted to accept military aid. On October 29, the American Ambassador called on Nehru offering any military equipment that India might need, and Nehru instantly accepted the offer.87 With the Cuban Missile Crisis also happening in October 1962, the Soviets Indias supporters through the 1950s were preoccupied and not offering too much attention to the Border War.88 This fact caused the Indians to court support from both England and the United States, and military supplies from both countries began arriving in early November.89 Moreover, the United States seemed eager to help India against the perceived menace of Communism.90 The Indian Parliament proclaimed a state of national emergency on November 8, adopting a resolution to drive out the aggressors from the sacred soil of India.91

84 85

Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. Ibid., Chapter V. 86 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 377. 87 Ibid., p. 378. 88 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter V. 89 Ibid., Chapter V. 90 Ibid., Chapter V. 91 Ibid., Chapter V.

28

These events during the lull in fighting did not bring about peace and ultimately led into the final phase of the war. In addition to seeking U.S. and British aid, Nehru also reinforced the troops. He stationed an additional 30,000 men in November in the border areas.92 On Nehrus birthday, November 14, the Indians also launched an ultimately unsuccessful counteroffensive along the eastern borders. With the Indians attacking, the PLA reinforced eight infantry and three artillery regiments along the eastern borders; four regiments at the middle section of the eastern borders and one regiment in the west, totaling 56,000 troops.93 The Chinese troops cut off supply lines in the east by encircling Indian forces on November 17. The following day, the Chinese launched an all-out attack on the Indian troops.94 Indian troops were forced to withdraw from Se La, leaving 48 Brigade at Bomdi La as the only organized Indian formation left in NEFA.95 The Chinese also simultaneously attacked in the western sector. On November 18, no Indian forces remained in Aksai Chin. The Chinese launched an attack on the last remaining troops in NEFA, and with the disintegration of 48 Brigade at about three oclock in the morning of November 20, 1962, no organized Indian military force was left in NEFA or the territory claimed by China in the western sector.96 Thus, November 20 marked militarily the Chinese victory as complete, and the Indian defeat absolute.97 The Chinese followed-through on their emphatic warnings toward the Indian forward policy, and the result of the war revealed important implications for both sides. The progression of Chinese assaults by date can be seen in Map 6.

92

Li Xiaobing, Sino-Indian Border War (1962), in China at War, edited by Xiaobing Li, (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2012), p. 400. 93 Ibid., p. 400. 94 Ibid., p. 400. 95 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 406. 96 Ibid., p. 408. 97 Ibid., p. 408.

29

Map 698:

98

Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 416.

30

On November 21 at midnight, Chou En-Lai and the Chinese announced ceasefire: Beginning from 00.00 on November 21st, 1962, the Chinese frontier guards will cease fire along the entire Sino-Indian border. Beginning from December 1st, 1962, the Chinese frontier guards will withdraw to positions 20 kilometres behind the line of actual control, which existed between China and India on November 7, 1959.99 The ceasefire agreement simply restated the compromise that China had been offering for years.100 China would keep Aksai Chin, which it viewed as extremely important, and both forces would retreat 20 kilometers from the McMahon Line.101 Regarding Aksai Chin and its strategic importance, Chou En-Lais ceasefire dictum made it clear that the Indians would keep their troops twenty kilometers back form the ceasefire line, and that China reserved the right to strike back if India did not do so.102 The Chinese troops began withdrawing December 1, as the ceasefire declared. They set up strong check points and posts to ensure their position in Aksai Chin in the west, and fully withdrew north of McMahon Line in the east.103 Regarding casualty figures from the war, the Indian Defence Ministry released these numbers in 1965: 1,383 killed, 1,696 missing, and 3,968 captured.104 According to Lieutenant Barnard, China released no casualty figures.105 However, Dr. Xiaobing Li wrote that according to Chinese reports. Total PLA casualties were 2,400 dead and wounded.106 Dr. Li also wrote that by the time China declared the ceasefire, both sides had engaged more than 100,000 troops.107

99

Ibid., p. 417. Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter VI. 101 Ibid., Chapter VI. 102 Ibid., Chapter VI. 103 Ibid., Chapter VI. 104 Maxwell, Indias China War, op cit., p. 424. 105 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter VI. 106 Li, China at War, op cit., p. 400. 107 Ibid., p. 399.

100

31

Indian Implications and Analysis Indias nonalignment foreign policy before the war allowed for low defense spending and a weak Indian Army; however, following the crushing defeat in 1962 at the hands of the Chinese, a realignment of foreign policy and consequently military structure was necessary. A comparison of the military forces in each country before the onset of war in 1962 revealed a far superior PLA force. The Peoples Liberation Army was estimated to have the strength of approximately three million officers and men in 1962.108 The central nature of the Chinese military allowed for a unified, single command of all Chinese land, sea, and air forces.109 The ground combat forces were organized in 130 divisions, mostly infantry, across eleven military regions. Weaknesses of the Chinese military at the onset of the war included: a struggling national economy leading to military cutbacks, a lack of Soviet military aid due to deteriorated relations, and tight control over the PLA, which prevented officer decision-making without authorization.110 Strengths of the PLA, especially relative to the Indians in the war, lied in its vastly greater size and number of forces, mobile preparedness, and preparedness for mountain warfare experience that had been gained in mountain and cold weather warfare in Korea. The Indian Ministry of Defence, the central agency for government policy decision on defense matters, oversaw the Indian Army, which was organized into three Commands: Western, Eastern, and Southern.111 The Army numbered over 400,000 at the time war broke out according to Brigadier Dalvi.112 The Indian Army faced significant personnel problems, having only eight divisions in 1962 seven infantry and one armored.113 To stress the sheer difference in 1962 of the size of

108 109

Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter III. Ibid., Chapter III. 110 Ibid., Chapter III. 111 Ibid., Chapter III. 112 Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder, op cit., p. 365. 113 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter III.

32

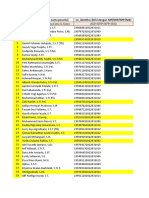

both sides forces and the number of divisions, the following two graphical representations were included.114 Graph 1: Graphical Representation of Differences in Military Size

1962 Military Strength

China

India

0 1,000,000 2,000,000 3,000,000

1962 Military Strength

Graph 2: Representation of Differences in Number of Army Divisions

1962 Army Divisions

India China

Indias total military personnel numbers were about 13.33% those of China in 1962, and China also had 122 more Army divisions.

114

33

Furthermore, weaknesses of the Indian military included: a minimal defense budget, resulting from the Nehru administrations refusal to believe India faced external threats; a shortage of experienced officers and non-commissioned officers post-independence because the British had previously provided leadership; inadequate intelligence; lack of preparedness for fighting at high altitudes and in cold weather; and a lack of mobility of the forces.115 The Indians did not truly possess any strength militaristically relative to the Chinese. The tremendous disparity in forces was reflective of the differences in Chinese and Indian foreign policies before the 1962 Border War. Such inequality allowed for a quick and decisive Chinese victory, and left the Indians humiliated. The Sino-Indian Border War resulted in a shift of Indian military and foreign policy and also had implications for Chinese strategy, particularly regarding its relations in the region. The reason the Indian government maintained such minimal military forces was directly related to its foreign policy. The Indians focused on peaceful cooperation and limited war aims if necessary. The forward policy was established with belief that the Chinese would not be militaristically aggressive against the Indians regardless of the number of Indian posts set up along the border. India was also bogged down by the Kashmir dispute with Pakistan, and referred the dispute with Pakistan to the United Nations for possible resolution.116 The nonalignment posture of India meant that India did not need a particularly large, modern, and well prepared force because all-out war seemed improbable. Instead limited approaches, such as the forward policy, could be pursued. However, that changed when the Chinese assault in October-November 1962 humiliated the Indians and warranted a change in Indian foreign policy.

115 116

Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter III. Sumit Ganguly and Manjeet S. Pardesi, Explaining Sixty Years of Indias Foreign Policy, India Review, vol. 8, issue 1, (Jan.-Mar. 2009): p. 7. Academic Search Premier.

34

Before the war, the Nehru administrations commitment to nonalignment led to the adoption of a particular set of policy choices. Specifically, one of the key elements of the doctrine of nonalignment was the limitation of high defense expenditures.117 India believed in the policy of Panchsheel, or the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, towards the PRC, which included mutual respect for each others territorial integrity and sovereignty; non-aggression; non-interference in one anothers internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence.118119 This explained the drastically limited expenditures of the Indian military even when steady evidence about a possible security threat from the PRC continued to mount.120 The nonalignment policy proved to be extremely costly when the border negotiations with the PRC ultimately reached a cul-de-sac in 1960.121 This dead-end led the Indians into the forward policy to attempt to restore its territorial claims along the Himalayan border. However, as Dalvi expressed, the forward policy was misguided and delusional. According to Indian Lieutenant Colonel J.R. Saigal, the Chinese came into our house, slapped us, and have gone back.122 Though after humiliating the Indians, ceasefire was reached, and the Chinese withdrew, borders still remained disputed between the two countries. The defeat led India to shift its foreign policy and consequently necessitated a military build-up. India learned several important military lessons from the 1962 Border War. First, India learned the danger in assumptions. Nehru assumed that China would not confront Indian troops and would passively retreat, but the assertive forward

117 118

Ibid., p. 7. Ibid., p. 7. 119 Panchsheel, the Indian term for the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, was written in the preamble of the Sino-Indian Tibetan agreement concluded in 1954 (Maxwell, Indias China War, op. cit. p. 79). 120 Ganguly and Pardesi, Explaining Sixty Years of Indias Foreign Policy, op cit., p. 7. 121 Ibid., p. 7. 122 Sali, India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector, op. cit., p. 88.

35

policy. brought retaliation from China.123 Assumptions were dangerous, and India needed to validate hypotheses about the enemy by accurate intelligence, which India lacked during the war.124 Related to this point, though both sides used reconnaissance patrols, the results of the confrontations showed that China had good intelligence and used it to good advantage, but India did not, and it needed to improve its intelligence gathering and application.125 India also learned not to ignore the counsel of senior army officers. These officers warned Nehru of Indias unpreparedness for war with China, but he ignored their advice, which proved disastrous for India. Brigadier Dalvi expressed that the Indian defeats at the hands of the Chinese, particularly at Thag La where he was captured, above all else resulted from the Governments failure to issue proper policy guidance and major directives.126 The Indian military also learned lessons on logistical readiness and preparedness for conditions. Whereas the Chinese had stockpiled supplies in Tibet, and had the manpower to keep the front well supplied, India lacked such logistical readiness, and even ran out of ammunition on several occasions during the war.127 The Indian military was also neither trained nor prepared for cold weather and mountain operations.128 The uniforms and equipment were not suitable for the high altitude conditions, reaching well over 10,000 feet at some battles. Finally, India learned the importance of generalship, leadership, and command and control.129 The Indian forces in the Western Command had strong organization and leadership. However, the opposite was true in NEFA, where there was often confusion, and numerous command changes resulted in disorganization and poor combat readiness.130 With these lessons learned, India embarked on a

123 124

Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter III. Ibid., Chapter III. 125 Ibid., Chapter VII. 126 Dalvi, Himalayan Blunder, op cit., p. 397. 127 Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter VII. 128 Ibid., Chapter VII. 129 Ibid., Chapter VII. 130 Ibid., Chapter VII.

36

substantial program of military modernization.131 The Indians made a commitment to the creation of a million-strong Army with ten new mountain divisions equipped and trained for high altitude warfare, a 45-squadron air force with a supersonic aircraft, and a modest program of naval expansion.132 India learned from the defeat, and took measures to improve its military capabilities, increasing military size and improving the preparedness and intangibles of the military. After 1962, there was a re-evaluation of Indias role in global politics, leading to the gradual shift away from the nonalignment policy.133 The United States provided assistance to India during and after the conflict, but the military cooperation between the two countries in the aftermath of the 1962 war was only fleeting as the United States disengaged itself from South Asia after the second Indo-Pakistani conflict in 1965 as it became increasingly preoccupied with the prosecution of the Vietnam War.134 From the Indian perspective, the United States, for all practical purposes, did not have interest or give attention to India.135 The Soviets sought to expand their influence in the subcontinent, by brokering a peace agreement between India and Pakistan in 1966.136 With the U.S. disengagement, Pakistan recognized an opportunity to expand the scope of its security cooperation with the PRC to balance Indian power, thereby contributing to a growing security nexus between Indias two major adversaries.137 Pakistan enjoyed the appearance of a weak India after the Border War of 1962, and with Chinese support felt in a favorable position to resolve lingering border disputes in

131 132

Ganguly and Pardesi, Explaining Sixty Years of Indias Foreign Policy, op cit., p. 8. Ibid., p. 8. 133 Nitya Singh, How to Tame Your Dragon: An Evaluation of Indias Foreign Policy Toward China, India Review, Vol. 11, No. 3 (2012), p. 143. Academic Search Premier. 134 Ganguly and Pardesi, Explaining Sixty Years of Indias Foreign Policy, op cit., p. 8. 135 Ibid., p. 8. 136 Ibid., p. 8. 137 Ibid., p. 8.

37

Kashmir.138 The reorganization and rebuilding of the Indian Army, however, alarmed Pakistan. These factors played a role leading to the Indian-Pakistan border war in Kashmir in 1965.139 Though India suffered a defeat in the Sino-Indian Border War, failing to achieve the border settlement that it desired when it initiated the forward policy under Nehru, there were still benefits in the loss. For one, the country emerged united as never before. The Communist Party in India lost the little clout it had in the country.140 India also took steps to move away from nonalignment, seeking foreign aid during the war, and fortifying its military in the wars aftermath. The nonalignment policy of Prime Minister Nehru was not well suited for India. His stubbornness in refusing to recognize the Chinese threat led him to develop and implement the faulty forward policy. Nehrus administration was not going to budge on the terms it desired regarding border resolution with China. The Chinese clearly asserted their militaristic might in the region, serving a blunt awakening for India. Though the shift in policy away from nonalignment was gradual for India, the 1962 defeated marked a transition in Indian foreign policy. Such a shift was necessary for the security interests of the country. The failure of the forward policy drew India into war with China and a debilitating defeat followed, yet still the resulting lessons learned and shift in Indian policy were in the best interest of the country. Before the war, Indian leadership failed to recognize its foreign policy and militaristic deficiencies, but after the defeat, Indias obvious choice was to transform its foreign policy and modernize the military.

138 139

Barnard, The China-India Border War of 1962, op. cit., Chapter VII. Ibid., Chapter VII. 140 Ibid., Chapter VII.

38

Chinese Implications and Analysis Ancient Chinese philosopher Xun Zi once said, One is always blinded by one-sided biases and could not see the full truth. Issues in China-India relations such as borders, history, and trade are merely brief episodes that should not blind people from seeing the full truth. We should believe that the governments, peoples, and intellectual elites of the two nations could take the 50th anniversary of the SinoIndian war as a point of departure, and work together toward building greater harmony between the two civilizations.141 The above is a quote from Global Times, one of the Chinese Communist Partys official voices to the outside world. Global Times is often regarded as the conservative and nationalisticsometimes even jingoisticChinese official media outlet covering international affairs. While liberal scholars and pundits frequently criticize its pro-government stance, the rhetoric of Global Times does reflect to a certain extent the positions of Chinas foreign policy makers. According to Global Times, the full truth of Sino-Indian relations can be found in several aspects: First, both civilizations are nurtured by rivers that originate from the Himalaya Mountains and the Tibet Plateau; second, there has never been any clash between the two civilizations during their centuries of exchange; third, the Mahayana doctrine has carried the essence of ancient Indian culture to China, where Indias past is preserved in the Chinese language; fourth, Buddhism has helped unify China in the aftermath of the Han Dynastys demise; fifth, China and India are the only civilization-sates among the worlds nation states; sixth, the world will benefit from a prosperous China and India, as the combined population of the two countries accounts for 40% of the entire human race.142 Such full truth, to some extent, is depicted as Chinas official foreign policy rhetoric toward India in media outlets such as the Global Times. Indeed, with respect to Chinese official posture, Chinese President Hu Jintao met with Prime Minister Singh on March 9, 2012. The two leaders jointly declared the

141 Tan Zhong, [Sino-Indian relations should not be clouded by the border conflicts], [Global Times], (22 October 2012) http://mil.huanqiu.com/observation/2012-10/3204641.html [accessed 1 November 2012], p.1. 142 Ibid., p.2.

39

year of 2012 as the Year of China-India Friendship and Cooperation.143 Yet diplomatic language does not always translate into smooth relations. Sohu.com, one of Chinas most popular portal websites recently featured a special topic titled Defeating India Only Requires 34 Days Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Sino-Indian Border War.144 On this special page decorated with militaristic graphics, Chinese editors listed detailed comparisons between Chinese and Indian arms, tracking the comparative development of Indian and Chinese weaponry as well as military strategies. Articles representing Indian perspectives are highlighted with provocative titles such as Indian joint chief: the 1962 fiasco will not repeat itself if going to war with China again, Senior Indian military officer calls for remembering the lessons from 1962 and arming the troops to the teeth, and India ridicules Chinese aircraft carrier.145 This unofficial, yet highly pronounced, hostility toward each other among Chinese and Indian elites leads us to resonate with the arguments presented in the article Historys Hostage: China, India and the War of 1962, which appeared in the Japanese current affairs magazine The Diplomat.146 The relationship between China and India is still haunted and often held hostage by the border war in 1962, notwithstanding rapid development of both economies, which resulted in much closer ties and frequent exchanges. Among the various disputes confronting China and India, Tibet remains a defining variable that shapes the direction of Sino-Indian relations in the contemporary context. As C. Raja Mohan correctly asserts, When there is relative tranquility in Tibet, India and China have reasonably good relations.

143

[Hu Jintao Meets with Indian Prime Minister Singh], [xinhua], (3 March 2012), http://news.xinhuanet.com/world/2012-03/30/c_122906905.htm [accessed 7 November 2012]. 144 34 [Defeating India Only Requires 34 Days Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Sino-Indian Border War],Sohu.com, < http://mil.sohu.com/s2012/zyzz/index.shtml>. 145 Ibid., Sohu.com. 146 Ivan Lidarev, Historys Hostage: China, India and the War of 1962, (21 August 2012), http://thediplomat.com/2012/08/21/historys-hostage-china-india-and-the-war-of-1962/ [accessed 27 October 2012].

40

When Sino-Tibetan tensions rise, Indias relationship with China heads south.147 Therefore in this section, we will use Tibet as the core issue in exploring the Chinese implications of the 1962 Sino-Indian War and thereafter position the Tibet issue at the center in the grand picture of Sino-Indian relations. If long before the war Tibet began to plague the relationship between Beijing and Delhi148, the war of 1962 consolidated such mutual suspicions and sealed the fate of the Tibet issue as an eternal source of tension in Sino-Indian relations.149 While these differences existed since the founding of the PRC, the 1962 war cemented evidence of how far both parties were willing to go, hence haunting bilateral relations ever since. With the presence of Dalai Lama and the Tibetan Government in Exile in Dharamsala, India remains the constant Chinese strain and ensures constant tensions between the two emerging powers. The continuous border disputes in the eastern and western sectors could be seen as the materialization of such tension: even today, while New Delhi still insists on its sovereignty over the Chinese-controlled Aksai Chin territory, Chinas territorial claim on the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh (illustrated by Map 7 below) has been a longstanding issue of concern for policy makers in both countries.

147 148

Lidarev, Historts Hostage, op cit.. Delhi, by then controlled by British government 149 Ibid..

41

Map 7: Arunachal Pradesh150

Regarding Chinese moves in the diplomatic dimension, the facts speak for themselves. In May 2007, China denied visa to Ganesh Koyu, an Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer who was scheduled to depart for a study trip to Beijing and Shanghai. The Chinese denied the visa to Officer Koyua resident of Arunachal Pradesh areabecause he is a Chinese citizen and therefore has no necessity to obtain a Chinese visa.151 In July 2009, China tried to block Indias request for a US$2.9 billion loan from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) because

150

Compare Infobase Pvt. Ltd., http://www.google.com/imgres?um=1&hl=en&sa=N&tbo=d&biw=1440&bih=799&tbm=isch&tbnid=AHId nwhu4Gr06M:&imgrefurl=http://www.vacationlink.htmlplanet.com/ARUNACHAL.html&docid=zSWTPe9k6M8tM&imgurl=http://www.vacationlink.htmlplanet.com/maparun.gif&w=640&h=480&ei=5Au sUKKPLIew0QHtnYGwBg&zoom=1&iact=rc&dur=432&sig=109217223172539444592&page=1&tbnh=141 &tbnw=188&start=0&ndsp=27&ved=1t:429,r:12,s:0,i:137&tx=82&ty=80. 151 China Denies Visa to IAS Officer from Arunachal, Financial Express (26 May 2007) http://www.financialexpress.com/news/china-denies-visa-to-ias-officer-from-arunachal/200132/ [accessed 15 November 2012].

42

the request included US$60 million for flood management, water supply, and a sanitation project in Arunachal Pradesh. In a Google search for the key words Asian Development Bank (yazhou fazhan yinhang), India (yindu), China (zhongguo) and 2009 in Chinese, the most widely recycled Chinese article claimed that this ADB document is a result of Indias little public relations trick and manipulations behind the scenes [

].152 Subsequently, in November 2009, Beijing took issue when the Dalai Lama

wanted to visit Tawang, a historic monastery town in Arunachal Pradesh. China restricted coverage of the visit by forbidding foreign journalists to accompany the Dalai Lama, as a consequence for New Delhis official permission for such a visit. "China expresses strong concern about this information. The visit further reveals the Dalai clique's anti-China and separatist essence," Jiang Yu, the spokeswoman for China's foreign ministry, said in a statement published by Reuters. She continued, "China's stance on the so-called 'Arunachal Pradesh' is consistent. We firmly oppose Dalai visiting the so-called 'Arunachal Pradesh'."153 It is exactly the so-called Arunachal Pradeshin official Chinese references, South Tibetthat has rekindled the border disputes and led to a new cycle of diplomatic accusations. The 1962 war has also militarized Chinas blame of Indian support to Tibetan separationists and Indian condemnation of Beijings suppressive policies in Tibet. From a Chinese perspective, China has upgraded its military presence in Tibet very close to the Line of Actual Control in Arunachal Pradesh by replacing its old liquid fuelled, nuclear capable CSS-3 intermediate range ballistic missiles with more advanced CSS-5 MRBMs.154 Not only has China deployed 300,000 Peoples

152 [ADB proposal and Indias Manipulation], Sina, (22 June 2012), http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2009-06-22/105918068716.shtml [accessed 2 November 2012]. 153 Krittivas Mukherjee, China Opposes Dalai Lama Trip to Arunachal Pradesh, Reuters (11 September 2009), http://in.reuters.com/article/2009/09/11/idINIndia-42388820090911 [accessed 10 November 2012]. 154 Namrata Goswma, Chinas Territorial Claim on Indias Eastern Sector, Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis Issue Brief, 19 April 2012, p. 5-6.

43

Liberation Army (PLA) troops on the Sino-Indian border, China has also enhanced PLAs airlift capacity by establishing airfields close to Tibet. Noteworthy is PLAs 23 Rapid Reaction Forces (RRFs), which have been significantly modernized in preparation for a limited war in the Himalayas. According to Namrata Goswami, an expert on Sino-Indian border conflicts, Formed in the 1990s after the first Gulf War, the RRFs main mission is to win or prevent highly intensive regional conflicts and enhance Chinas military capabilities in a hi-tech environment using the latest in military technology. Significantly, the RRFs possess the airlift capacity to reach the India-China border in 48 hours. Also to be noted is the fact that the six RRF divisions stationed at Chengdu are always in an operational readiness mode, capable of operating in all kinds of terrain. Of critical importance to India is the fact that the RRFs train in Southwest China (Yunnan), a terrain very similar to that in Arunachal Pradesh. In actuality, forces like RRFs will be the first line of offence used by China in its occupation of Arunachal Pradesh and resistance against the forward movement of the Indian Army in the event of conflict. In reaction to Chinas military build-up, the Indian Defense Ministry already passed a $13 billion military modernization program on November 2, 2011, which will affect nearly 100,000 Indian border troops in the next five years.155 The militarization on both sides results in frequent stand-offs and occasional incidents between Chinese and Indian soldiers. In September, Global Times reported on the intensity of military standoff at the Tawang Monastery.156 Although India and China took a major confidence building step in January, setting up an institutionalized border mechanism that allows for

155

Prashanth Parameswaran, Sino-Indian Border Negotiations: Problems and Prospects, The Jamestowns Foundations China Brief, Vol.12, Issue 6 (2012). http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=39141 [accessed 16 October 2012]. 156 Cheng Gang, , [In South Tibet, the skirmish between China and India occurs on a daily basis], [Global Times], (21 September 2012), http://world.huanqiu.com/depth_report/2012-09/3134786.html [accessed on 18 October 2012].

44