Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Basic Principles of Management For Cervical Spine Trauma

Hochgeladen von

105070201111009Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Basic Principles of Management For Cervical Spine Trauma

Hochgeladen von

105070201111009Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Eur Spine J (2010) 19 (Suppl 1):S18S22 DOI 10.

1007/s00586-009-1118-2

REVIEW ARTICLE

Basic principles of management for cervical spine trauma

J. K. ODowd

Received: 23 July 2009 / Published online: 22 August 2009 Springer-Verlag 2009

Abstract This article reviews the basic principles of management of cervical trauma. The technique and critical importance of careful assessment is described. Instability is dened, and the incidence of a second injury is highlighted. The concept of spinal clearance is discussed. Early reduction and stabilisation techniques are described, and the indications, and approach for surgery reviewed. The importance of the role of post-injury rehabilitation is identied. Keywords Trauma Cervical spine Review Assessment Treatment

focussed assessment, the important way points of a full classication of the skeletal and spinal cord injury, the principles of early prioritisation and decision making, the outline of the surgical strategy including indications, timing, approaches, technique and post-operative care, and the outline principles of rehabilitation.

Initial stabilisation During the resuscitation and initial assessment phase, the cervical spine should be assumed to be injured and should be splinted using a cervical spine collar, two sandbags and a forehead tape. The thoracolumbar spine should be stabilised on a spine board for transfer and then on a at emergency room trolley allowing log rolling with in-line stabilisation at the neck only (Fig. 1).

Introduction The management of spinal trauma ranges from dealing with patients with trivial injuries requiring no interventive treatment, through to major complex, spinal cord and life threatening spinal column injuries. Extensive experience is required for the optimum assessment, decision making and treatment of this patient group and, in this article, the principles of early management and treatment will be outlined. Traditionally, management of injuries of the cervical spine have been a bolt-on extra in managing the multiply injured patient, but the widespread adoption of the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocols has highlighted the importance of assuming a cervical spine injury in all patients with a history of trauma until proven otherwise. In the context of the advanced management of spinal injuries, this chapter will outline the main points of the

J. K. ODowd (&) The RealHealth Institute, 23-31 Beavor Lane, London W6 9AR, UK e-mail: johnodowd@btinternet.com

Evaluation The main principles of evaluation are: assessing and classifying the skeletal injury, assessing and classifying the neurological injury, assessing associated spinal injuries, identifying associated non-spinal injuries and establishing treatment priorities during the assessment phase.

Instability Instability has been dened [8] as the loss of the ability of the spine under physiological loads to maintain its pattern

123

Eur Spine J (2010) 19 (Suppl 1):S18S22

S19

Fig. 1 Stabilisation of cervical spine before clearance

of displacement so that there is no initial or additional neurological decit, no major deformity and no incapacitating pain. It is not only important to identify instability but also to identify injuries, which whilst having no overt features of instability have the potential to displace and cause a neurological injury and/or chronic pain and disability. The assessment of instability assists in the initial management of the patient particularly with potential instability, but an understanding and grading of instability is critical to determining denitive management and its presence is likely to mandate a surgical approach to the spinal injury. Finally, the identication of instability aids in giving the patient, a prognosis early on in the treatment process, and aids the patients decision-making process.

Clinical assessment Details of clinical assessment and classication are covered elsewhere in this volume. Nonetheless, the principles of assessing, the injuries are fully integrated with the early decision making and the principles are reiterated here.

Skeletal injury The increased use of the two-column model for describing injuries to the spinal column rather than the previously used three column model, has not only simplied the process of classication but also focuses the clinician on assessing, using all possible modalities, both the anterior and the posterior columns [7]. It is the failure of identication of a signicant injury in the posterior column that the most frequently leads to a misunderstanding of prognosis for anterior column fractures and leads to unexpected deterioration in some patients.

The clinician has to integrate clinical assessment including history and examination, plain X-ray, CT scan, both planar and two- or three-dimensional reconstructions and MRI scan. The output of these assessments should be a clear description of the injury to the anterior and posterior columns and this will lead to the classication of the injury as described elsewhere in this volume. Injuries to the anterior column typically occur with compression or exion compression injuries and are the least amenable to identication by examination. The anterior column, however, is clearly visualised in plain X-rays, and in all modalities of CT scanning. Two-dimensional CT reconstruction helps in identifying type B fractures and in combination with three-dimensional reconstruction gives a better visualisation of some fracture patterns in the anterior column. Whilst the MRI scan rarely adds signicant additional information to the assessment of the anterior column it can be helpful in quantifying the degree of injury to the adjacent disc and other soft tissue. The posterior column from occiput to sacrum is readily accessible to the clinician in a patient who is log rolled with in-line stabilisation of the cervical spine. A careful search for localised tenderness, bruising and a gap or step is essential. High quality plain radiography can sometimes demonstrate interspinous distraction and, of course, with gross two-column injury then scoliosis and/or subluxation/dislocation will be seen on anterior posterior X-ray. Two-dimensional CT reconstructions and the MRI scan are powerful modalities for identifying injuries in the posterior column. Dynamic X-rays are rarely used acutely, but if there is a residual question about stability, then clinical assessment of neck and trunk control is very helpful, and should be augmented by erect X-rays. At the end of the assessment, phase of the skeletal injury the clinician should have a good idea of the conguration and magnitude of the injury to the anterior and posterior columns and using the Magerl classication [7] reproducible descriptive terms can be used for this injury and the injury allocated to the numerical hierarchy of this classication. The assessment of spinal cord injury is dealt with elsewhere; essentially, the clinical and radiological assessments, especially, the MRI scan should allow the clinician to identify the anatomical and functional level of the spinal cord injury, the degree of spinal cord injury, i.e. partial or complete and some quantication of the degree of soft tissue damage to the cord, including the presence of spinal shock.

Associated injuries Up to 20% of spinal injuries occur at multiple levels and there is evidence that in the upper cervical spine one

123

S20

Eur Spine J (2010) 19 (Suppl 1):S18S22

1. 2.

3.

An awake patient with no spinal symptoms. An awake patient with localised pain, normal plain imaging, CT scanning and normal exion, extension X-rays of the painful part. The problems arise obtunded or unconscious patient. Patients with a normal X-ray and ne slice CT scan can be said to have a 98% chance of no signicant spinal injury, particularly unstable injuries or subluxation. Even the addition of MRI scanning, however, does not give a 100% clearance and the recommended advice is that if plain X-ray and CT or MRI are normal then the intensive care staff should be instructed that there is only a very low chance of a potential instability in the spinal column, and that they should continue to use a lightweight orthosis and to log roll the patient until criteria one or two above can be met.

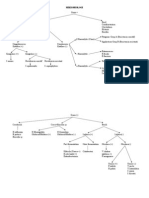

Fig. 2 Two level cervical injury

Steroid protocol There is continued controversy around the role of high dosage Methylprednisolone in reducing the impact of spinal cord injury [2] and these issues will be dealt with in a separate article in this volume. Each hospital, region or country will have their own protocol and accepted standard of care but if the local preference is to use the steroid protocol then this should be instituted as soon as the spinal cord injury has been diagnosed and this may well be very early on in the assessment process.

identied injury is associated with an 80% chance of a second injury in the cervical spine (Fig. 2). The assessing clinician should therefore assume a second injury, and all patients with a signicantly identied skeletal injury in the spinal column should have the whole spinal column examined clinically and assessed radiologically either with plain X-rays from occiput to sacrum or with rapid sequence multidetector CT. This protocol should also be adopted in the unconscious polytraumatised patient where a clinical assessment is unreliable. Injuries of the spinal column are always associated with signicant energy application to the patient and on this basis, as per ATLS protocols [4], careful and repeated search for non-spinal, visceral and other skeletal injuries should be carried out. The experienced spinal clinician should be establishing treatment priorities during the assessment process so that at the end of this process not only are the skeletal, neurological and associated injury are quantied but also an outline treatment plan has been completed.

Treatment principles and specic management of the spinal injured patient The principles of treatment are as follows: decompress neurological structures, restore vertebral column integrity, anterior column and posterior tension band,

avoid and manage complications, and approach and implant

Clearance Clearance is an important concept, which is essential to intensive care physicians managing obtunded or unconscious patients. Management of these patients is simplied if a spinal injury has been excluded and the spinal surgeon is often called upon to review a patient and exclude such an injury. There is good evidence that a spinal injury can only be comprehensively excluded in the following circumstances:

facilitate rehabilitation.

Many patients can be managed non-operatively and in the cervical spine the options for non-operative treatment range from the application of a lightweight orthosis through to a reduction with halo traction and rigid stabilisation with a halo jacket. There is a gradual change in the acceptability of halo jacket treatment for unstable cervical

123

Eur Spine J (2010) 19 (Suppl 1):S18S22

S21

spinal injuries and much as the management of tibial fractures has migrated from a non-operative treatment approach to operative stabilisation, there is a similar shift in trends for managing unstable cervical spine injuries. Traction applied with a halo rather than tongs, however, can always be used as the emergency treatment in any displaced injury of the cervical spine except a Hangmans type IIA [6] fracture. In the Hangmans type, IIA fracture traction may displace the fracture and adds dramatically to the risk of spinal cord injury and subsequent death. In all patients with a displaced cervical spine injury, in whom a closed reduction by traction is being attempted, the clinician should perform an MRI scan other than when this is impossible to achieve in the treating centre and there is clinical urgency to the reduction. The following injuries can be treated on traction: displaced Jefferson fracture, Hangmans fracture, type II/type III odontoid peg fracture, displaced subaxial fracture and subaxial sub-luxations and dislocations.

Fig. 3 Isolated anterior column injury

In general terms, traction can be used to maintain reduction after reduction is achieved and to let the dust settle in patients who are polytraumatised. The use of a halo jacket can be used for transfer to a specialist unit and for denitive treatment in certain injuries. The fast reduction protocol has been well-described in the literature [5] and involves halo application under local anaesthetic in an awake patient. The patient should be monitored in a high-dependency unit and in-line traction with X-ray control with 2 kg increments every 15 min to a limit of approximately 60 kg. This protocol has been described as reducing nearly all subaxial displaced injuries.

Fig. 4 Complex two-column injury

Surgical indications In determining, which patients are suitable for surgery, the grade of instability as manifested by the degree of injury to the two spinal columns, or any signicant displacement should be considered (Figs. 3, 4). A surgical option should be balanced against the non-surgical option by using an evidence-based approach to predict the likely outcome in relation to neurological sequelae, pain, deformity and degenerative change with one or other treatment method. Early surgical intervention can be considered for partial neurological injury. There is evidence that a surgical decompression and stabilisation within 6 h of a partial spinal cord injury will lead to 70% of patients improving by one or more American Spinal Injuries Association, International Medical Society of Paraplegia (ASIA IMSOP) grades [3]. If, such surgery is delayed beyond 6 h,

there is only a 12% chance of such improvement. In patients with a complete spinal cord injury, the situation is much bleaker but early decompression may allow recovery of one nerve root level and this will have dramatic functional implications in the cervical spine. In the thoracolumbar spine, a systematic review [1] of the literature looking at 275 publications and showed a mean improvement in Frankel grade of 0.64 in the operative group and 0.82 in the non-operative group. One study had a neurological deterioration as a result in the surgical group. The strong conclusion of this paper is that there is no justication in the thoracolumbar spine for early surgical intervention to improve the neurological outcome. Indication for surgical stabilisation in subaxial fractures Failure of closed reduction. Unstable injuries.

123

S22

Eur Spine J (2010) 19 (Suppl 1):S18S22

Initially, e.g. bilateral facet dislocation of more than 25% or 11. Dynamic studies. Progressive neurological deterioration. For early mobilisation in neurologically compromised patient. In patients with a high incidence of late complications, e.g. kyphosis of 30 or loss of height of more than 50%. Established late instability and post-traumatic kyphosis.

The degree of kyphosis and loss of height is an important prognostic factor in type A compression fractures in the cervical spine.

mobilise as soon as they have recovered from the anaesthetic effects and in the absence of spinal cord injury they will be up and walking within a day of the surgery. In patients with a spinal cord injury, there will be a period of acclimatisation to gravitational challenge but most spinal cord injury rehabilitation centres will now commence tilting into an upright position within 48 h of surgical stabilisation. There is still certain inertia around the spinal cord rehabilitation community to commence this ultra early mobilisation programme but one of the main benets of modern surgical stabilisation is to allow such early mobilisation.

Surgical approach The cervical spine can be decompressed and/or stabilised from anterior and/or posterior approaches. In order to some extent, the approach depends upon the following factors: 1. 2. 3. Surgeons preference. Direction of maximum cord compression. Biomechanical factors favour the posterior approach to reconstruct the tension band in single approach surgery. The clinical results, however, favour anterior approaches. Whilst biomechanically inferior, there appears to be a very high clinical success rate with anterior approaches. Most surgeons confronting patients with a severe twocolumn disruption will consider anterior and posterior combined approach and this should certainly be contemplated in patients in whom there is evidence of residual instability after completion of a rst stage either posterior or anterior. This may be assisted by intraoperative stress X-rays. The detail of the surgical approaches and techniques will be covered elsewhere in this volume.

Conclusion The aim of the treating surgeon should be to reverse and certainly prevent deterioration of the neurological injury, to either identify adequate spinal stability to allow early mobilisation or to achieve such stability by the use of modern surgical techniques such that patients can be rapidly rehabilitated to their previous study, social and sporting activities.

Conict of interest statement potential conict of interest. None of the authors has any

4.

References

1. Boerger TO, Limb D, Dickson RA (2000) Does canal clearance affect neurological outcome after thoracolumbar burst fractures. J Bone Joint Surg 85:629635 2. Fehlings MG (2001) Recommendations regarding the use of methylprednisolone in acute spine cord injury. Spine 26:S56S57 3. Fehlings M, Aarabi B, Dvorak M, et al. (2008) A prospective multicenter trial to evaluate the role and timing of decompression in patients with cervical spinal cord injury: initial one-year results of the STASCIS study. Paper presented at the AANS meeting in Chicago 4. Kortbeek JB, Al Turki SA, Ali J et al (2008) Advanced trauma life support, 8th edition, the evidence for change. J Trauma 64:1638 1650 5. Lee AS, MacLean JC, Newton DA (1994) Rapid traction for reduction of cervical spine dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg 76:352 356 6. Levine AM, Edwards CC (1985) The management of traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg 67A:217226 7. Magerl F, Aebi M, Gertzbein SD, Harms J, Nazarian S (1994) A comprehensive classication of thoracic and lumbar injuries. Eur Spine J 3:184201 8. White AA, Panjabi MM (1990) Clinical biomechanics of the spine. J.B. Lippincott Co, Philadelphia

5.

Post-operative care and rehabilitation In the modern world of spinal injury care, there is no expectation of patients lying in bed for weeks or indeed months following trauma. If a spinal injury is not stable enough to allow the patient to mobilise within 2448 h with appropriate bracing, then surgical stabilisation should be considered. After surgery patients should be free to

123

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Article 2Dokument9 SeitenArticle 2105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- UNV Call For Papers On Volunteering and Governance ISTR MuensterDokument1 SeiteUNV Call For Papers On Volunteering and Governance ISTR Muenster105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Apgar ScoreDokument6 SeitenApgar Score105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Guide From International Trauma Life SupportDokument9 SeitenGuide From International Trauma Life Support105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- HemorrhoidsDokument2 SeitenHemorrhoids105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Importance of Trauma Systems and The Vital Role of Nursing in Trauma SystemsDokument2 SeitenThe Importance of Trauma Systems and The Vital Role of Nursing in Trauma Systems105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Principles of Management For Cervical Spine TraumaDokument6 SeitenBasic Principles of Management For Cervical Spine Trauma105070201111009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- CKD Pocket GuideDokument2 SeitenCKD Pocket GuideLutfi MalefoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toxic Epidermal NecrolysisDokument13 SeitenToxic Epidermal NecrolysisHend AbdallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sesion 2 Articulo Caso Clinico 1 Urticaria PDFDokument16 SeitenSesion 2 Articulo Caso Clinico 1 Urticaria PDFQuispe Canares MariangelesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acr 2016 Dxit Exam Sets - WebDokument129 SeitenAcr 2016 Dxit Exam Sets - WebElios NaousNoch keine Bewertungen

- DC Kit2 ObadiaDokument2 SeitenDC Kit2 ObadiaErnesto KangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety Seal Certification ChecklistDokument2 SeitenSafety Seal Certification ChecklistKathlynn Joy de GuiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acog Embarazo Gemelar 2004 PDFDokument15 SeitenAcog Embarazo Gemelar 2004 PDFEliel MarcanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ketidakseimbangan Elektrolit (Corat Coret)Dokument5 SeitenKetidakseimbangan Elektrolit (Corat Coret)jendal_kancilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiovascular Examination: Preparation of The PatientDokument4 SeitenCardiovascular Examination: Preparation of The PatientLolla SinwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Open Book FractureDokument31 SeitenOpen Book FractureMUHAMMAD ADLI ADNAN BIN JAMIL STUDENTNoch keine Bewertungen

- EUOGS OSCE Booklet 2020Dokument26 SeitenEUOGS OSCE Booklet 2020Amanda Leow100% (1)

- Ma. Lammatao: Trion AKG Marble LLCDokument11 SeitenMa. Lammatao: Trion AKG Marble LLCNasir AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vox Sanguin Mei 2021Dokument159 SeitenVox Sanguin Mei 2021rsdarsono labNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scenar Testimonials (Updated)Dokument10 SeitenScenar Testimonials (Updated)Tom Askew100% (1)

- Toxicology-Handbook PDFDokument2 SeitenToxicology-Handbook PDFssb channelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tipos de SuturasDokument5 SeitenTipos de SuturasLeandro PeraltaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quisted en P Menopausicas Guias GTG - 34 PDFDokument32 SeitenQuisted en P Menopausicas Guias GTG - 34 PDFAdela Marìa P LNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peptic Ulcer DiseaseDokument22 SeitenPeptic Ulcer DiseaseJyoti Prem UttamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dumitrita Rodica Bagireanu U4 Assessment Feedback2 (PASS)Dokument4 SeitenDumitrita Rodica Bagireanu U4 Assessment Feedback2 (PASS)Rodica Dumitrita0% (1)

- Mci Ayn Muswil PtbmmkiDokument49 SeitenMci Ayn Muswil PtbmmkiLucya WulandariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Extrapyramidal System DisordersDokument41 SeitenExtrapyramidal System DisordersAyshe SlocumNoch keine Bewertungen

- B-Blood Banking History 2-4-21: RequiredDokument5 SeitenB-Blood Banking History 2-4-21: RequiredFlorenz AninoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asbestos Awareness Quiz #1: AnswersDokument2 SeitenAsbestos Awareness Quiz #1: AnswersMichael NcubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MyxedemaDokument3 SeitenMyxedemaBobet ReñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commentaries: PEDIATRICS Vol. 113 No. 4 April 2004Dokument5 SeitenCommentaries: PEDIATRICS Vol. 113 No. 4 April 2004Stephen AttardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mikrobiologi DiagramDokument2 SeitenMikrobiologi Diagrampuguh89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using A Dense PTFE Membrane Without Primary Closure To Achieve Bone and Tissue RegenerationDokument5 SeitenUsing A Dense PTFE Membrane Without Primary Closure To Achieve Bone and Tissue RegenerationDiego SiqueiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pem Quiz: Respiratory Emergencies Peter S. Auerbach, MDDokument3 SeitenPem Quiz: Respiratory Emergencies Peter S. Auerbach, MDPhanVHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flagile X SyndromeDokument2 SeitenFlagile X Syndromeapi-314093325Noch keine Bewertungen

- DrowningDokument22 SeitenDrowningNovie GarillosNoch keine Bewertungen