Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Mental Disability Rights Immigration Proceedings

Hochgeladen von

marioma12Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

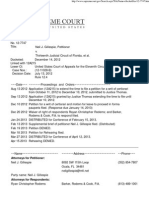

Mental Disability Rights Immigration Proceedings

Hochgeladen von

marioma12Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HearingDifficultVoices:TheDue ProcessRightsofMentallyDisabled IndividualsinRemovalProceedings

ALICECLAPMAN* ABSTRACT

Every day, immigration judges face unrepresented respondents who present signs of severe mental impairment and possible incompetence. They are given no resources for, or guidance on, how to address the situation. Every day, noncitizens with mental impairments are ordered removed from the United States even though, if their stories were actually heard, they might be found eligible for relief. This Article provides both theoreticalandpracticalguidancetothedecisionmakerswhomustaddress the problem. The Article describes the current situation, in which various adjudicators respond to the problem in various ways, often by glossing over it. Next, the Article sets out a legal argument derived from different strands of dueprocess jurisprudence(due process inremoval proceedings, civil due process generally, and due process with respect to mentally impaired litigants) for why additional procedural protections are necessary. Finally, the Article identifies safeguards that would be feasible and adequate, such as setting a clear competency standard requiring both passive and active abilities; imposing disclosure duties on the Department of Homeland Security and investigative duties on the immigration judges; creating an expert panel within the Department of Justice to perform competency evaluations; revising procedural rules to require judges to focus on objective evidence where an applicant is incapable of satisfying the current standards for credible testimony; providing for skilled, court appointed representation where necessary (in some cases in a hybrid,

* Clinical Teaching Fellow, Center for Applied Legal Studies, Georgetown Law; incoming Visiting Assistant Professor & Director, Immigrant Rights Clinic, University of Baltimore School of Law; J.D. Yale Law School; B.A. Princeton University. I am grateful to Daniel Hatcher,GeoffreyHeeren,DavidLuban,AndrewSchoenholtz,andPhilipSchragforvaluable comments and suggestions. This Article was supported in part by a research grant from the UniversityofBaltimoreSchoolofLaw.

373

374

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

guardianadvocate role); and authorizing immigration judges to terminate proceedings in the rare case in which no other safeguard would be adequate.

INTRODUCTION

arlos,1 an immigrant from Latin America who had lived in the United States for 24 years, came to the attention of the immigration authorities when voices in his head told him to set himself on fire.2 This was not the first or last time he would obey these voices and attempt suicide,3butitwasaturningpointinhislife.Thistime,hisactionsresulted in a plea conviction of unlawfully causing a fire.4 Two years later, on the basis of this conviction, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) tookhimintocustodyandbeganremovalproceedingsagainsthim.5 Like most detained respondents (approximately eightyfour percent),6 Carlos was unrepresented. He did not inform the Immigration Judge (IJ) that he suffered from chronic paranoid schizophrenia and frequently hallucinated.7 Nor did the DHS trial attorney inform the IJeven though the DHS was holding him in detention, treating him with increasing dosages of psychotropic medications (which he sometimes refused), and receiving medical treatment reports that Carlos was suffering from acute

1Namechangedtopreserveanonymity. 2See CAPITAL AREA IMMIGRANT RIGHTS (CAIR) COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, PRACTICE MANUAL FOR PRO BONO ATTORNEYS REPRESENTING DETAINED CLIENTS WITH MENTALDISABILITIESINIMMIGRATIONCOURTapp.23,at3,22(2009)[hereinafterCAIRCOAL.& COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP], http://www.caircoalition.org/probonoresources/pro bonomentalhealthmanual/ (publishing a redacted copy of Carloss Motion to Reopen to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA)). As explained below, many facts of this case are also knowntotheauthorfirsthand. 3Seeid.atapp.23,at22. 4Id.atapp.23,at2. 5Id.

Removal proceedings are held before an Immigration Judge (IJ), within the ExecutiveOfficeforImmigrationReview(EOIR)oftheDepartmentofJustice(DOJ).See8 U.S.C. 1229a(a)(1) (2006). These proceedings are adversarial and relatively formal: An attorneyrepresentstheDepartmentofHomelandSecurity(DHS)initseffortstoremovethe respondent. See 8 C.F.R. 1240.2(a) (2010). Respondents are entitled to retain counsel through their own efforts, but if they cannot find counsel they must present their own case. 8 U.S.C. 1229a(b)(4)(A)(statingthatsuchcounselmaybepresentatnoexpensetotheGovernment).

6See NINA SIULC ET AL., VERA INST. FOR JUSTICE, IMPROVING EFFICIENCY AND PROMOTING JUSTICE IN THE IMMIGRATION SYSTEM: LESSONS FROM THE LEGAL ORIENTATION PROGRAM 1 (2008), available at http://www.vera.org/download?file=1780/LOPpercent2BEvaluation_May 2008_final.pdf. 7CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.23, at 3 (publishing aredactedcopyofCarlosMotiontoReopentotheBIA).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

375

psychotic episodes, hearing screaming voices, and unable to eat or sleep.8 (Even more disturbing, knowing all this, the DHS still had Carlos sign a waiver of his right to seek certain benefits.)9 The IJ did not make her own inquiry, or attempt to obtain the state records that would have reflected recentobservationsaboutCarlosssevere,uncontrolledmentalillness.10 Although the regulations forbid accepting concessions of removability from incompetent respondents,11 and although the DHSs allegations of removability were questionable,12 the IJ found Carlos removable based on his own admissions.13 Carlos applied for asylum and other fearbased forms of relief from removal. He submitted a written statement that he feared persecution in his home country for having evaded conscription. The IJ called Carlos to the witness stand. During Carloss testimony, his head was pounding, he was hearing voices, and he did not understand what was happening. When asked whether he was afraid to return to his native country, he answered no. The IJ denied Carloss asylum application basedin large part on the inconsistency between hiswritten statement that hewouldbeindangerandhisapparentoraltestimonytothecontrary.14 Carlos remained in detention awaiting removal. His fellow detainees noticed his delusional, selfdestructive behavior and knew something was very wrong.15 I happened to be in regular contact with one of these detainees at the time, and he told me Carloss story. With help from fellow detainees and a changing coalition of advocates (of which I was one), Carlos appealed his removal order up to the court of appeals, narrowly avoided removal (the DHS had already set his physical transfer in motion when a judicial stay halted it), and was eventually released into his community after having suffered more than two years of immigration detention. Had a concerned fellow detainee not found outside help for Carlos, he would have disappeared into his native country, a country to which he feared returning and in which he may have been locked up in a mentalinstitutionunderhorrificconditions.16 Nadine,17 another mentally disabled citizen, had better luck with the removal system. She was not detained and was well enough to contact the

8Id.atapp.23,at2628. 9Id.atapp.23,at26. 10Id.atapp.23,at3. 118C.F.R.1240.10(c)(2010). 12See CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.23, at 42 (publishingaredactedcopyofCarlosMotiontoReopentotheBIA). 13Id.atapp.23,at3. 14Id. 15Id.atapp.23,at4. 16Seeinfranote207andaccompanyingtext. 17Namechangedtopreserveanonymity.

376

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

Georgetown Law clinic (where I teach) before her immigration case had been decided. Nadine was a political refugee from a dictatorial regime, targeted because of her daughters political activities. The police had imprisoned and raped Nadines daughter. After Nadine had helped her daughter escape the country, the police had returned to Nadines home andbeatenherunconscious. Nadine had severe posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as cognitive limitations that we suspected were manifestations of a traumatic brain injury from the beating. Although she seemed competent to make her own decisions in the case, Nadine was a challenging client for various reasons. Because of her own confusion and fear of recalling the past, she could not help her student representatives frame, polish, or corroborate her story of pastandfearedpersecution.Vitaldetailswouldemergeonlyafterweeksof interviewing; contact information for witnesses would come out accidentally,almosttoolatetobeuseful.Duringinterviews,shecouldonly last for short periods of time before she felt a burning in her head and could no longer respond to questions. The students exhausted themselves trying to piece together a coherent narrative that would hold up at the hearingandtosupportthatnarrativewithwitnessstatementsandphysical andmentalevaluations. At the hearing, the government produced documents contradicting Nadines chronology of the case, and her answers on cross examination made little sense. The judge was troubled by her unreliability as a witness. Although IJs usually rule orally at the end of the hearing, he reserved judgment and asked for written closings. In their closing, the students made a strong factual and legal case for why the IJ should find Nadine credible despite the flaws in her testimony. Ultimately, the IJ did grant Nadine asylum. If all goes well, in a few years, she will be a citizen. I feel certain, though, that if she had appeared unrepresented, she would have losthercaseandbeenorderedremoved. Together,CarlossandNadinesstoriesillustratetheplightofmentally disabled noncitizens in the removal system. Individuals vary greatly in the degree of their incapacitation, from Carlos, who was completely unable to look after his own interests, to Nadine, who simply needed extensive help telling her story. Many are in detentionin 2008 the DHS estimated that somewhere between 7571 and 18,929 immigration detainees suffered from serious mental illness18and some are not. And some, like Nadine,

18HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH & AM. CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT: MENTAL DISABILITY, UNFAIR HEARINGS, AND INDEFINITE DETENTION IN THE US IMMIGRATION SYSTEM 1617 (2010) [hereinafter DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT], available at http://www.hrw.org/ sites/default/files/reports/usdeportation0710webwcover_1_0.pdf. Internal numbers cite a higher figure of 15% of the detained immigrant population on any given day approximately57,000peoplein2008.Id.(citingDanaPriest&AmyGoldstein,SuicidesPointto

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

377

manage to find outside help in time, whereas others, like Carlos, either remain in detention and in legal limbo for years, or worse are removed withouteverhavinghadameaningfulopportunitytobeheard. Even under ordinary circumstances, immigration court proceedings are so rushed that one IJ described them as being like holding death penalty cases in traffic court.19 When mentally disabled individuals appear before IJs, often without representation, those IJs are wholly unable toaffordthemameaningfulhearing.Partoftheproblemisthelackoflegal guidance. Thus far, all the relevant authoritiesCongress, the Board of Immigration Appeals, the Attorney General, and the courts of appeals have avoided setting any minimum standards of fairness in such circumstances. Another part of the problem is a lack of any practical guidance or resources that might enable judges to respond to signs of incompetency. InthisArticle,Ifirstsetoutthecurrent situationinimmigrationcourts with respect to mentally disabled respondents; then I address the legal question of whether additional safeguards are required; and finally I propose how, practically speaking, the courts could provide additional safeguardssufficienttoensuredueprocess. I. CurrentSituation

The Immigration and Nationality Act, in language dating from 1952, directs the Attorney General to prescribe safeguards to protect the rights and privileges of a noncitizen where it is impracticable by reason of an aliens mental incompetency for the alien to be present at the proceeding.20 The Congress that enacted this provision did not specify what it meant for an individual to be present, and in particular whether physical presence was sufficient or whether, in addition, some actual capacitytoparticipatewasnecessary.Norhavetheotherbranchesclarified this statutory issue. The Attorney General has, however, created some limited safeguards for incompetent respondents, including: regulations permitting other representatives to appear on the individuals behalf;21 special service requirements;22 and a requirement that the immigration courtholdahearingonanyissueofremovabilityratherthanacceptingan admission of removability from an unrepresented respondent who is incompetent . . . and is not accompanied by an attorney or legal

GapsinTreatment,WASH.POST,May13,2008,atA1).

19Julia Preston, Lawyers Back Creating New Immigration Courts, N. Y. TIMES, Feb. 9, 2010, at

A14 (quoting Dana L. Marks, Immigration Judge, President, National Association of ImmigrationJudges)(referringtothenatureofasylumcases).

208U.S.C.1229a(b)(3)(2006). 218C.F.R.1240.4(2010). 22Id.103.5a(c)(2).

378

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

representative, a near relative, legal guardian, or friend.23 The regulations do not establish any standard for competence or for doubt as to competency. Nor do they establish procedures for inquiring into competency or provide guidance for how to proceed where an individual, whether represented or unrepresented, is found incompetent or otherwise severely impaired. They do not specify, for example, whether the judge should attempt to secure counsel or other assistance for the individual, or howthejudgeshoulddeveloptherecordifshecannotrelyprimarilyonthe individualstestimonyassheusuallydoes. Legislators and policymakers, it seems, have long been aware that the existing regulations are insufficient. More than a decade ago, the Department of Justice (DOJ) solicited comments on whether to promulgate regulations for appointing guardians ad litem (GALs)24 in removalproceedings.25Veryfeworganizationsrespondedonthesubjectof GALsformentallydisabledrespondents,probablybecauseadvocateswere far more concerned about other contemporaneous changes in the law such as the creation of a oneyear filing deadline for asylum applications.26 Several organizations expressed vague approval of the idea of a GAL program, while a few cautioned that such a program would not in and of itself solve the problem.27 The DOJ subsequently undertookover thirteen yearsagotofurtherexaminethecomplexandsensitiveissue.28 More recently, some members of Congress have expressed concern about the lack of progress on this issue. In February 2009, representatives introduced language into an appropriations bill encouraging the Executive

23Id.1240.10(c). 24Aguardianadlitemis[a]guardian,usu[ally]alawyer,appointedbythecourttoappear

inalawsuitonbehalfofanincompetentorminorparty.BLACKSLAWDICTIONARY774(9th ed.2009).

25See Inspection and Expedited Removal of Aliens; Detention and Removal of Aliens; ConductofRemovalProceedings;AsylumProcedures,62Fed.Reg.444,448(Jan.3,1997). 26Seeid.at463. 27Severalorganizationsfiledcommentsinresponseto62Fed.Reg.444withtheDirectorof PolicyDirectivesandInstructionsBranchoftheINSin1997.Foranexampleofcomments,see Letter from Florence Immigrant & Refugee Rights Project, Inc., to Dir. Policy Directives & Instructions Branch, INS (Jan 31, 1997) (on file with author); Letter from Gay Mens Health Crisis, Inc., to Dir. Policy Directives & Instructions Branch, INS (Jan. 30, 1997) (on file with author); Letter from Lutheran Immigration & Refugee Serv., to Dir. Policy Directives & Instructions Branch, INS (Jan. 31, 1997) (on file with author); Letter from Mass. Law Reform Inst., to Dir. Policy Directives & Instructions Branch, INS (Jan. 31, 1997) (on file with author); Letter from U.S. Comm. For Refugees, to Dir. Policy Directives & Instructions Branch, INS (Jan.29,1997)(onfilewithauthor).

Inspection and Expedited Removal of Aliens; Detention and Removal of Aliens; Conduct of Removal Proceedings; Asylum Procedures, 62 Fed. Reg. 10312, 10322 (Mar. 6, 1997).

28See

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

379

Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) to work with experts and interested parties in developing standards and materials for immigration judges to use in conducting competency evaluations of persons appearing before the courts.29 This language, however, was not included in the final version of the legislation.30 Further, in December of 2009 representatives instructed EOIR to report on what steps [the DOJ] has taken to provide safeguards for the rights of aliens judged to be mentally incompetent, as requiredby8U.S.C.1229a(b)(3),31buteventhishesitantlanguagewasleft out of the final version of that appropriations bill.32 For its part, EOIR recently added a section on mental incompetence to its Immigration Judge Benchbook, suggesting, as best practices, that judges us[e] direct, simple sentences, build a very good record, and consider appropriate and necessary actions such as attempting to recruit representation or grant[] multiple continuances with the goal of securing representation, being mindful, however, of the importance of deciding detained cases expeditiously.33 The Benchbook also suggests that termination might be appropriate in some cases, while acknowledging that the Board of ImmigrationAppeals(BIAorBoard),whichitselfispartofEOIR,has not upheld a case that terminated proceedings based on a theory that the respondent was so incompetent as to render the proceedings unfair.34 These tentative halfmeasures suggest the political branches recognize the problem as significant but lack the consensus, political will, or both to addressit. Every day, meanwhile, individuals who manifestly lack the ability to defend their own rights appear in immigration court. Judges have responded inconsistently.35 Some have contacted nonprofit legal service

29155CONG.REC.H1762(dailyed.Feb.23,2009). 30Compare id., with Omnibus Appropriations Act of 2009, Pub. L. No. 1118, 123 Stat. 524, 570. 31155CONG.REC.H13884(dailyed.Dec.8,2009). 32Compare id., with Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2010, Pub. L. No. 111117, 123 Stat. 3034,3123. 33Exec. Office for Immigration Review, Dept of Justice, Mental Health Issues, IMMIGRATION

JUDGE BENCHBOOK, http://www.justice.gov/eoir/vll/benchbook/tools/MHI/index.html (last visitedApr.8,2011).

34Id. IJs can terminate proceedings at the request of either partyfor example, because a charging document is defective, DHS has not met its burden of establishing removability, or for various other reasons. See Exec. Office for Immigration Review, Dept of Justice, Motions, IMMIGRATION JUDGE BENCHBOOK, http://www.justice.gov/eoir/vll/benchbook/tools/Motions% 20to%20Reopen%20Guide.htm (last visited Apr. 8, 2011). Termination does not necessarily preventDHSfrominitiatingnewproceedingsatanytime,althoughatleastonecourthasheld that the government cannot reopen proceedings based on evidence it could have discovered priortotermination.RamonSepulvedav.INS,743F.2d1307,130910(9thCir.1984). 35How IJs and DHS are treating respondents with mental impairments, and how they should be treating them, are extremely sensitive issues at the moment, in part because the

380

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

providers or individual private attorneys to obtain representation for a potentially incompetent respondent,36 administratively terminated or closed proceedings37 or ordered the DHS to conduct a competency evaluation and/or secure legal representation for the individual.38 Others have granted multiple continuances in the hopes that the respondents mental state will change or that he will miraculously find his own counsel.39 Too many have done nothing and simply treated the individual like any other respondent in proceedingsparticularly when the individuals disability is not noticeably disruptive.40 The DHS, for its part,

respondents are the subject of current and potential litigation and in part because their cases raise thorny issues about how to allocate scarce resources. The author conducted a number of interviews to gather information about the current situation and about the concerns of inside actors, but these individuals were only willing to share their thoughts and information anonymously.

36Telephone Interview with anonymous government official (Oct. 15, 2010) (notes on file with author); Telephone Interview with anonymous private immigration attorney (Aug. 24, 2010) (notes on file with author); see also TEX. APPLESEED, JUSTICE FOR IMMIGRATIONS HIDDEN POPULATION 57 (2010), available at, http://www.texasappleseed.net/index.php?option=com _docman&task=doc_download&gid=313&Itemid= (describing one case in which the court held six hearings with no progress before locating pro bono counsel for the respondent (who wasdetainedallthewhile)). 37See, e.g., First Amended ClassAction Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief

and Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus at 4, FrancoGonzales v. Holder, No. 10CV02211 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 2, 2010) [hereinafter FrancoGonzales Complaint] (on file with author) (describing an administratively closed case in which, after closure, the plaintiff remained in detention nearly five years until, shortly after filing a complaint in federal court, he was released); CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.16, at 23 (publishing a redacted Decision of the Immigration Judge from New York, New York). Administrative closure, in contrast with termination, does not resolve DHSs charges against the respondent but merely removes a case from the judges docket with the consent of both parties. DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at 74. Either party can request that the proceedingsberecalenderedatanytime.Ifarespondentisinimmigrationdetentionwhenhis case is closed, he remains in detention unless he successfully applies for bond. 8 C.F.R. 1003.19 (2010). In certain circumstances, however, the IJ would not have any authority to order him released. See id. 1003.19(h)(2)(i). Some mentally disabled individuals have languished in detention for years because their cases were closed. DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at 74. Although this issue is beyond the scope of the Article, an important regulatoryreformwouldbetogiveIJsgreaterauthoritytoorderrespondentsreleased.

38See, e.g., CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.17, at 3

(publishingaredactedInterimOrderoftheImmigrationJudge,Arlington,VA).

39 One judge, facing a respondent who was previously declared incompetent to stand trial on criminal charges and was appearing by videoconference from a psychiatric hospital, granted the respondent three continuances to find an attorney, and when that failed the IJ proceeded to hold a hearing anyway and order the respondent removed. See Mohamed v. TeBrake, 371 F. Supp. 2d 1043, 1047 (D. Minn. 2005), vacated, Mohamed v. Gonzales, 477 F.3d 522,525(8thCir.2007).

40See,

e.g., Amended Order Re Plaintiffs Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, at 68,

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

381

has disavowed any obligation to raise mental competency issues with the court.41 And in some cases, IJs have even allowed detention and removal officers from the DHS to appear on behalf of disabled individuals (as their custodians)athearingsinwhichaDHSattorneyisarguingforremoval42 as clear a conflict of interest as can be imagined but one expressly authorizedbythecurrentregulations.43 Similarly, the BIA has taken various positions on the issue of incompetency, always in unpublished, non precedential decisions. The Board has: remanded cases where a judge failed to determine competency;44 instructed judges to take reasonable measures to obtain an attorney or other representative to assist a respondent;45 ordered the DHS to appoint an attorney;46 instructed judges to proceed with the sole

FrancoGonzales v. Holder, No. CV 1002211 DMG (DTB) (C.D. Cal. 2010); CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.22, at 410 (publishing a redacted Appeal Brief of Respondent to the BIA, In re RH (seeking appeal based on IJs failure to inquire as to respondents mental capacity)); see also DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at32(quotingaprivateattorneysobservationthat[u]nlesstheyareactuallyyellingatyouor notparticipating,apersonwith mentalillnesswontberecognized).IJs mayfeelconstrained in their response by BIA caselaw holding that they lack any jurisdiction to decide constitutional issues such as whether the current regulations fail to provide adequate safeguards. See In re FuentesCampos, 21 I. & N. Dec. 905, 912 (B.I.A. 1997). And although there is no reason EOIR could not apply the avoidance of constitutional doubt canon when interpreting statutes and regulations, the BIA has never done so in a published opinion. Several BIA Members have, however, joined in dissents citing this canon. See, e.g., In re Rojas, 23 I. & N. Dec. 117, 13839 (B.I.A. 2001) (Rosenberg, Board Member, dissenting); In re Garvin Noble, 21 I. & N. Dec. 672, 699702 (B.I.A. 1997) (Rosenberg, Board Member, dissenting); In re ValdezValdez,21I.&N.Dec.703,718(B.I.A.1997)(Rosenberg,BoardMember,dissenting).

41See Brief for Am. Immigration Council et al., as Amici Curiae Supporting Respondent at 7, In re LT (Sept. 14, 2010) [hereinafter Brief for AIC], available at http://www.legalaction center.org/sites/default/files/docs/lac/MatterofLT91410.pdf; DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at 34; Emily Ramshaw, Mentally Ill Immigrants Have Little Hope for Care When Detained, DALL. MORNING NEWS, July 13, 2009, available at 2009 WLNR 13763431 (noting that, where a detainee is diagnosed with mental illness, its rare for DHS to disclose this diagnosistothecourt). 42Brief for AIC, supra note 41, at 2224; FrancoGonzales Complaint, supra note 37, at 5; Telephone Interview with anonymous government lawyer (Oct. 15, 2010) (notes on file with author). 43See 8 C.F.R. 1240.4 (2010) (stating that where all other representatives may be unavailable the custodian of the respondent shall be requested to appear on behalf of respondent). As many immigrants in removal proceedings are detained, their custodian is a DHSofficer.BriefforAIC,supranote41,at22. 44See,e.g.,InreGreenTatum,2010WL3536700,at*1(B.I.A.Aug.13,2010). 45See, e.g., CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.18, at 2

(publishingaredactedDecisionoftheBoardofImmigrationAppeals).

46See, e.g., id., at app.21, at 3 (publishing a redacted Decision of the Board of Immigration AppealsfromDec.8,2003).

382

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

safeguard of not accepting admissions from an incompetent respondent;47 reversed decisions terminating proceedings (in other words, considered and rejected the position that removal ought to be halted because of competency issues);48 and affirmed removal orders where the judge failed to adapt the hearing in any way.49 Courts of appeals, for their part, have acknowledged in passing that mentally incompetent noncitizens might be entitled to some additional protections, while skirting the issue in various waysfor example, by finding that counsel had effectively presented the petitioners best case in immigration court,50 that a petitioner failed to present sufficient evidence of mental incompetency or of prejudice,51 or

47See, e.g., id., at app.19, at 3 (publishing a redacted Decision of the Board of Immigration AppealsfromFeb.3,2006(remandingthecasetoanIJfornewproceedingsandorderingthat suchproceedingsshouldcomplywith8C.F.R.1240.10(c))).8C.F.R.1240.10(c)requiresthat [t]he immigration judge . . . not accept an admission of removability from an unrepresented respondentwhoisincompetent.8C.F.R.1240.10(c). 48See In re JFF, 23 I. & N. Dec. 912, 91415 (A.G. 2006) (recounting procedural history of case, in which IJ had terminated proceedings based on the respondents mental incompetence and the BIA had reversed); DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at 49 ([T]he DHS and BoardofImmigrationAppealshavebothrebukedIJsforactivelyengaginginfactfindingand addingtotherecordinappellatedecisions,resultingintheassumptionthatjudgeswhoassist an unrepresented person with diminished capacity will have their decisions overturned.); Exec. Office for Immigration Review, Dept of Justice, In re SY, IMMIGRATION JUDGE BENCHBOOK 45 (June 3, 2009), http://www.justice.gov/eoir/vll/benchbook/tools/MHI/ templates/SY%20%28BIA%20June%203,%202009%29.pdf (publishing a redacted decision of the Board of Immigration Appeals reversing a termination order where incompetent respondentwasrepresentedandhadfamilymemberspresent).

Mohamed v. TeBrake, 371 F. Supp. 2d 1043, 1045 (D. Minn. 2005) (noting BIA affirmance of removal order issued against unrepresented, disabled individual with no competency assessment) vacated, Mohamed, 477 F.3d 522, 525 (8th Cir. 2007); CAIR COAL. & COOLEY, GODWARD, KRONISH, LLP, supra note 2, at app.23, at 45 (publishing a redacted Respondents Motion to Reopen to the Board of Immigration Appeals, Mar. 2008 (appealing BIA summary affirmance of IJs decision despite IJs failure to make a competency determination)).

50SeeNeeHaoWongv.INS,550F.2d521,523(9thCir.1977). 51See MuozMonsalve v. Mukasey, 551 F.3d 1, 6 (1st Cir. 2008); Mohamed, 477 F.3d at 527; Nelson v. INS, 232 F.3d 258, 26162 (1st Cir. 2000). In an unpublished decision, Margaryan v. Mukasey,aNinthCircuitpanelremandedanadversecredibilitydetermination,reasoningthat the petitioners inconsistencies might have been a result of mental impairment or incompetence.261F.Appx44(9thCir.2007).Thecourtalsofoundthat[a]sylumregulations recognize that the interests of an incompetent person involved in adversary proceedings should be represented by a party who possesses adequate discretion and mental capacity, citing to 8 C.F.R. 1240.4, which permits representatives to appear on behalf of a mentally incompetent individual or, in the alternative, provides that the court should request that a custodian appear on his behalf. Id. at 46. The fact that the court reached this result in an unpublished decision and declined to base its remand on any due process or statutory ground, or decide whether, when, and how IJs must hold competency hearings, suggests a reluctance (for whatever reason) to set a precedent that would require massive systemic

49See

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

383

thatapetitionerwasentitledtoremandonothergrounds.52 In other words, there is no agency or judicial consensus as to what evidence casts doubt on competency or how IJs should respond to such evidence. Given the complexity of the problem and the variety of circumstances that may affect the fairness of any particular hearing, a legislative or regulatory response is necessary. On the assumption that such a response will only come with judicial prompting, I now turn to the legalargumentforreform. II. LegalAnalysis Although the particular legal issue of what safeguards are due to incompetent or otherwise disabled individuals in removal proceedings is unresolved, three interrelated strands of law provide guidance: first, the rights of noncitizens in removal proceedings generally; second, the rights of individuals involved in civil matters where fundamental interests are at stake; and third, the rights of individuals in both civil and criminal proceedings who suffer from mental disabilities such that they cannot protecttheirowninterests.53Iwilldiscusstheseinturn.

change. Two district courts have found that mental incompetence, or signs of possible incompetence, does trigger additional requirements, although one of these cases has been vacated and the other has yet to be reviewed by the Court of Appeals. See Mohamed, 371 F. Supp. 2d at 1047(holding, based on the regulations, that it is an abuse of discretion when an immigration judge, faced with evidence of a formal adjudication of incompetence or medical evidence that an alien has been or is being treated for the sort of mental illness that would render him incompetent, fails to make at least some inquiry), vacated, Mohamed, 477 F.3d at 525(explainingthatthedistrictcourttransferredthecasetocircuitcourtbasedon106ofthe Real ID Act of 2005, which stripped the district courts of jurisdiction over the matter); Amended Order Re Plaintiffs Motion for a Preliminary Injunction at 38, FrancoGonzales v. Holder, No. CV 1002211 DMG (DTB) (C.D. Cal. 2010) (holding, based on the Rehabilitation Act,thatEOIRwasrequiredtoprovideQualifiedRepresentativesformentallyincompetent respondentsintheirremovalproceedings).

52Ruiz v. Mukasey, 269 F. Appx 616, 619 (9th Cir. 2007) (declining to reach due process argument because remand was appropriate based on IJ error as to the nature of petitioners conviction).Onedistrictcourtdeniedahabeaspetitionbyamentallyillimmigrationdetainee, finding that the petitioner was not entitled to any additional safeguards because, although plainly delusional at his immigration hearing, he had been competent enough to articulate hisbeliefthathewouldbepersecutedinTurkey.SeeOrderonReportandRecommendation, at8,Gokce v. Ashcroft,No.02CV02568ORD(W.D.Wash.2003).Thecourtsopinion,which is somewhat shocking for its minimalist reading of the due process clause, can be read either asestablishingahollowstandardofcompetencyorasholding,morebroadly,thatwhatever the capacity of an individual respondent, the system complies with due process simply by providing him with various (useless) procedural protections such as the right to present evidence. Id. at 89 (rejecting report and recommendation by magistrate judge that the court appoint counsel under the Criminal Justice Act). Either interpretation is inconsistent with the dueprocesscaselawsetforthininfrasectionII. 53There are statutory arguments

available as well. One would be based on 8 U.S.C.

384

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

A. DueProcessinImmigrationProceedings The principle that removal cases are civil in nature and therefore subject only to limited dueprocess requirements has survived for over a hundredyearseventhoughitwasfirstarticulatedinadecisionthatisnow infamous (atleast amongacademics)for its open xenophobia: thesocalled Chinese Exclusion case.54 The author of that oftquoted opinion, Justice Field, reasoned that the congressional power to exclude noncitizens was inherent in national sovereignty, to protect against aggression and encroachment... from vast hordes of foreigners of a different race crowding in upon us.55 Subsequent decisions such as Nishimura Ekiu v. United States reinforced this principle of national sovereignty, without the inflammatory rhetoric, by tying the executive and congressional powers over immigration to their foreignrelations powers.56 These decisions all assumed without explanation that, for the governments powers to be effective,removalproceedingshadtobecivilratherthancriminalinnature (and therefore subject to minimal standards and minimal judicial oversight). The Court began to moderate its position toward the middle of the twentieth century. Without casting aside the civilcriminal distinction, it nonetheless began scrutinizing executive actions more closely and reading statutoryprotectionsmoreexpansivelyinrecognitionofthedrastic57and grave58 nature of removal, and of the high and momentous stakes in removal proceedings.59 In Bridges v. Wixon, the Court sounded poised to override the criminalcivil distinction when it reversed a deportation order

1229a(b)(4)(B) (2006), which guarantees that respondents have a reasonable opportunity to present their case, and another is based on 1229a(b)(3), which directs the Attorney General to prescribe safeguards to protect mentally incompetent respondents. See 8 U.S.C. 1229a(b)(4)(B), (b)(3) (2006). These provisions, in their vagueness, merely restate the Due Process Clause. See U.S. CONST. amend. XIV 1. Another statutory protection is based on section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and its implementing regulations, which require federal agencies in the course of operating systems such as immigration courts to provide reasonable accommodations to individuals with disabilities. 29 U.S.C. 794(a); see also Amended Order Re Plaintiffs Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, at 2638, FrancoGonzales v. Holder, No. CV 1002211 DMG (DTB) (C.D. Cal. 2010) (finding that the respondents qualified for reasonable accommodations under the Rehabilitation Act). The intricacies of theselegalargumentsarebeyondthescopeofthisArticle.

54SeeChaeChanPingv.UnitedStates(ChineseExclusionCase),130U.S.581(1889). 55Id.at606. 56142U.S.651,659(1892). 57FongHawTanv.Phelan,333U.S.6,10(1948). 58Jordanv.DeGeorge,341U.S.223,231(1951). 59Delgadillov.Carmichael,332U.S.388,391(1947).SeealsoNgFung Hov.White,259U.S.

276,284(1922)(recognizingthatdeportationmayresultalsoinlossofbothpropertyandlife; orofallthatmakeslifeworthliving).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

385

based on unsworn statements about the petitioners alleged communist affiliation,60reasoning:

Here the liberty of an individual is at stake. . . .Though deportation is not technically a criminal proceeding, it visits a great hardship on the individual and deprives him of the right to stay and live and work in this land of freedom. That deportation isapenaltyattimesamostseriousonecannotbedoubted.61

In view of the stakes, the Court warned, [m]eticulous care must be exercised lest the procedure by which [an individual is removed]... not meettheessentialstandardsoffairness.62 Although the civilcriminal distinction survived Bridges v. Wixon (and isinperfecthealth),theCourthascontinuedtorespondtothefundamental interests at stake in removal proceedings. Given that deportation is a drastic measure and at times the equivalent of banishment or exile, the Court has applied a rule of lenity in interpreting removal provisions similar to that in criminal proceedings, construing statutory ambiguities in the noncitizens favor.63 [I]n view of the grave nature of deportation, the Court has also applied the void for vagueness doctrine.64 The Court has adopted a presumption against retroactivity somewhat akin to the ex post facto prohibition in criminal law, to narrowly construe the temporal scope of various criminal bars to discretionary relief from removal.65 And most recently, in Padilla v. Kentucky, the Court acknowledged that deportation is. . . intimately related to the criminal process and, as a consequence, held that noncitizen criminal defendants have a constitutional right to effectivecounselingontheimmigrationconsequencesofaconviction.66 Individual lower courts and appellate judges at times (though not recently) have shown even more willingness to question the categorization of immigration law as an ordinary civil proceeding, at least with respect to legalresidentsfacingremovalasaconsequenceofacriminalconviction.In AguileraEnriquez v. INS, for example, the Sixth Circuit recognized that due process would require appointment of counsel for a noncitizen in removal proceedings if that noncitizen would require counsel to present his positionadequatelytoanimmigrationjudge.67Thecourtnotedpriordicta to the contrary, but dismissed this dicta as rest[ing] largely on the outmodeddistinctionbetweencriminalcases(wheretheSixthAmendment

60326U.S.135,15657(1945). 61Id.at154;seealsoNgFungHo,259U.S.at284. 62Bridges,326U.S.at154. 63FongHawTanv.Phelan,333U.S.6,10(1948)(citingDelgadillo,332U.S.at391). 64Jordanv.DeGeorge,341U.S.223,231(1951). 65INSv.St.Cyr,533U.S.289,31526(2001). 66130S.Ct.1473,148182(2010). 67516F.2d565,568n.3(6thCir.1975).

386

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

guarantees indigents appointed counsel) and civil proceedings (where the Fifth Amendment applies).68 (The court denied the petition for review, however,becauseitfoundthatunderthelaw,therewasnoreliefforwhich counsel could have helped AguileraEnriquez apply.)69 The dissent in AguileraEnriquez went even further, rejecting the majoritys casebycase approach and reasoning that [a] deportation proceeding so jeopardizes a resident aliens basic and fundamental right to personal liberty70 that only a per se rule requiring appointment of counsel will assure a resident alien dueprocess oflaw.71 Andin UnitedStatesv. CamposAsencio, another court remanded a case to district court after holding that, depending on how the facts of the case developed, the governments refusal to provide counselforanoncitizeninremovalproceedingsmighthaveamountedtoa dueprocess violation.72 These cases, now decades old, offer a glimpse of whatthelawmightlooklikeifcourtsactuallymeasuredtheprocessduein removalproceedingsbythegravityoftheinterestsatstake. Thus far, however, the special status of immigration proceedings has translated into very few procedural protections. Principally, individuals can reopen proceedings if the representation they received was ineffective;73 the immigration judge has an affirmative duty to develop the record;74 and nonEnglishspeaking respondents have a right to accurate and complete translation during proceedings.75 Whether these protections could be expanded to include counsel under certain circumstances

68Id. 69Id.at569. 70Id.at571(DeMascio,J.,dissenting). 71Id.at573. 72822F.2d506,509(5thCir.1987). 73Courts have limited this right with various qualifications. See Jezierski v. Mukasey, 543 F.3d 886, 890 (7th Cir. 2008) (denying a general right to effective assistance, but recognizing that [t]he complexity of the issues, or perhaps other conditions, in a particular removal proceeding might be so great that forcing the alien to proceed without the assistance of a competent lawyer would deny him due process of law by preventing him from reasonably presenting his case); Khan v. Atty Gen., 448 F.3d 226, 236 (3d Cir. 2006) (holding that to make out an ineffective assistance claim a petitioner must show (1) that he was prevented from reasonably presenting his case (quoting Uspango v. Ashcroft, 289 F.3d 226, 231 (3d Cir. 2002)) and (2) that substantial prejudice resulted (quoting Anwar v. INS, 116 F.3d 140, 144 (5th Cir. 1997))); Hernandez v. Reno, 238 F.3d 50, 55 (1st Cir. 2001) ([W]here counsel does appear for the [alien], incompetence in some situations may make the proceeding fundamentallyunfairandgiverisetoaFifthAmendmentdueprocessobjection.);InreLozada, 19I.&N.Dec.637,639(B.I.A.1988)(settingforthstrictproceduralrequirements). 74The IJs duty to develop the record derives partly from 8 U.S.C. 1229a(b)(1), which authorizesandinstructsIJs toreceiveevidence, andinterrogate, examine,andcrossexamine the alien and any witnesses, but also from the Due Process Clause. See, e.g., Jacinto v. INS, 208F.3d725,72728,732(9thCir.2000)(quoting8U.S.C.1229a(b)(1)(2006)). 75PerezLastorv.INS,208F.3d773,778(9thCir.2000).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

387

dependsonasecondlineofcaselawtowhichInowturn:civildueprocess whereimportantindividualinterestsareatstake. B. CivilDueProcess The Supreme Court has required appointment of counsel in certain highstakes civil proceedings: for example, in involuntarycommitment proceedings76 and in juveniledelinquency proceedings.77 In Lassiter v. Department of Social Services, a divided Court drew a line around these precedents, based on the fact that they all concerned a threatened deprivation of physical liberty.78 The Court held that, unlike individuals at risk of losing their physical liberty, indigent parents facing a stateinitiated proceeding for termination of parental rights were not categorically entitled to counsel.79 Instead, such cases would be evaluated individually under the general Mathews v. Eldridge factors governing what protections are constitutionally required for any particular civil procedure: (1) the private interests at stake; (2) the governments interests; and (3) the risk of an erroneous decision in the absence of the safeguard at issue.80 In a twist on Mathews, however, these factors would be considered against a presumptionthat counsel is not required if physical liberty is notat stake.81 Interestingly, state high courts have proved far more willing than the Lassiter Court to require appointment of counsel in civil proceedings involving parental rights or other fundamental interests, but this is limited consolationforunsuccessfulfederallitigants.82 Lassiter might not apply to removal proceedings because,in contrast to the termination of parental rights, removal arguably implicates physical liberty.83 In Bridges v. Wixon, for example, the Court characterized the

76SeeVitekv.Jones,445U.S.480,49697(1980). 77SeeInreGault,387U.S.1,41(1967). 78452U.S.18,26(1981). 79Id.at31. 80Id.(citingMathewsv.Eldridge,424U.S.319,335(1976)). 81Id. 82See, e.g., In re K.L.J., 813 P.2d 276, 279 (Alaska 1991); State ex rel. Johnson, 465 So.2d 134,

138 (La. Ct. App. 1985); cf. Lavertue v. Niman, 493 A.2d 213, 218 (Conn. 1985) (providing an indigent defendant the right to counsel in paternity proceedings); Corra v. Coll, 451 A.2d 480, 487 (Pa. Super. Ct. 1982) (granting a blanket right to counsel for putative fathers in paternity actions).

83Lassiter comes up only twice in the numerous discussions of due process in removal

proceedings: one Supreme Court case and one court of appeals case, both citing Lassiter in passing for the principle that [t]he constitutional sufficiency of procedures provided in any situation...varieswiththecircumstances.Landonv.Plasencia,459U.S.21,34(1982);accord United States v. BenitezVillafuerte, 186 F.3d 651, 656 (5th Cir. 1999). The holding in Lassiter also might not apply to an incompetent individuals removal proceeding because Lassiter involvedapetitionerwhowascompetenttopresentherowncase.

388

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

noncitizens interest in remaining here as a liberty interest.84 Of course, liberty could mean either physical liberty as the absence of physical coercion or a broader concept of liberty as selfdetermination; Lassiter recognized only the former as giving rise to a blanket right to counsel, and the Court did not specify in Bridges which sort of liberty was at stake in removal proceedings. Regardless, physical coercion has become a routine aspect of the removal process. Over the past twenty or so years, Congress has prescribed detention for an increasing number of noncitizens in removal proceedings, often for long periods of time.85 (the DHS is even authorized to continue detaining individuals who win at the trial level whileitappealsthesedecisionstotheBIA.)86In2009,forexample,theDHS detained approximately 383,000 noncitizens in prisonlike conditions.87 Some immigration detainees spend years in detention.88 Moreover, noncitizens are often physically restricted with shackles or other restraints duringtheremovalprocess.89 Thus,nowmorethanever,removalproceedingsentailadeprivationof physical liberty in some sense. Of course, the DHS would no doubt respond that this argument proves too much: If removal proceedings implicate physical liberty as the Court understands that term, then all noncitizens facing removal, and not just the most vulnerable among them, are entitled to representation. (Though unlikely to attract any court majority anytime soon, this was the dissents view in AguileraEnriquez v. INS.)90Evenifcourtsrejectedtheconceptionofremovalasadeprivationof physical liberty akin to involuntary commitment, they could still take the middle ground presented by Gagnon v. Scarpelli, a probationrevocation case.91 In that case, the Court characterized the interest at stake as conditional liberty and applied a casebycase analysis. Contrary to

84326U.S.135,154(1945). 85SeeGeoffreyHeeren,Pulling Teeth:TheStateofMandatoryImmigrationDetention,45HARV. C.R.C.L.L.REV.601,61011(2010)(describingenactmentof mandatorydetentionin1988and gradualexpansionsincethenoftheclassofnoncitizenssubjecttodetention). 86See8U.S.C.1003.6(c)(Supp.2010). 87OFFICE OF IMMIGRATION STATISTICS, IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS 1 (2009), available at http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/enforcement_ar_2009 .pdf; DORA SCHRIRO, DEPT OF HOMELAND SECURITY, IMMIGRATION DETENTION OVERVIEW AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2, 6 (2009) [hereinafter SCHRIRO REPORT], available at http://www.ice.gov/ doclib/about/offices/odpp/pdf/icedetentionrpt.pdf. 88SCHRIROREPORT,supranote87,at6. 89See, e.g., Nina Bernstein, A Mother Deported, and a Child Left Behind, N.Y. TIMES, Nov. 24, 2010, at A1; Meribah Knight, Deportations Brief Adios and Prolonged Anguish, CHI. NEWS COOPERATIVE (May 9, 2010), http://www.chicagonewscoop.org/deportation%E2%80%99s briefadiosandprolongedanguish/. 90AguileraEnriquezv.INS,516F.2d565,57374(6thCir.1975)(DeMascio,J.,dissenting). 91441U.S.778,779(1973).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

389

Lassiter, however, the Court presumed a right to representation for anyone with a colorable claim.92 Lassiter acknowledged this middleground proposal in passing before focusing its analysis on what due process requiresintheabsenceofanyphysicallibertyinterest.93 Even assuming that removal cases fall under Lassiter, that case merely creates a presumption that could well be overcome by the Mathews factors in cases involving mental incompetence.94 As for the first Mathews factor, the interests in having a meaningful hearing and in avoiding removal are significant. For many noncitizens, removal can mean separation from family, friends, and community; loss of a home, employment and a business; or other significant hardships. Individuals often face deportation to a country that they left at a very young age, where they might not even speakthelanguage.Theseindividualsarerelativelyluckycomparedtothe refugees who face persecution, torture, or even death if they are wrongfully removed to the countries from which they fled. As noted in PartII.A,theCourthasacknowledgedthegravityofalloftheseinterests.95 Applying the second Mathews factor, the government has a clear interest in efficiency and economy, but this interest may not militate strongly against providing protections for a highly limited class of noncitizens, particularly because cases involving this class already require extra resources in the form of repeated continuances, prolonged hearings, administrative closures and reopenings, administrative and judicial appeals, remands, prolonged detention, and treatment. Appointed representation, although costly, would allow for more efficient legal resolutions, which would offset some of the cost.96 Moreover, the

92Id.at79091. 93Lassiterv.DeptofSoc.Servs.,452U.S.18,28,31(1981). 94Seeid.at27. 95Admittedly, the interest at stake in Lassiterparental rightsis extremely important as well, as the Lassiter opinion itself acknowledged. Id. at 27. The most significant differences between that case and the situation of mentally impaired individuals in removal proceedings are: (1) mentally impaired individuals are uniquely at risk of losing meritorious claims, and (2) in custodytermination proceedings the main issue generally is the parentchild relationship, a subject on which most parents are uniquely qualified to make their case, whereas immigration law raises all kinds of technical questions about how various convictions should be classified, what bars apply to what forms of relief, and whether the precise criteria for each form of relief are met. In other words, the main differences lie in the thirdMathewsfactor(riskofanerroneousdecision).

AM. BAR ASSN, REFORMING THE IMMIGRATION SYSTEM: PROPOSALS TO PROMOTE INDEPENDENCE, FAIRNESS, EFFICIENCY, AND PROFESSIONALISM IN THE ADJUDICATION OF REMOVAL CASES 510 (2010), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba /migrated/Immigration/PublicDocuments/aba_complete_full_report.authcheckdam.pdf.Inthe context of Legal Orientation Program (by which EOIR funds legal service providers to visit detention facilities and educate detainees about the law), EOIR has recognized that such servicesmorethanpayforthemselvesbecausetheymakeproceedingsmoreefficientandhelp

96See

390

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

government also has an interest in a fair adjudicative system, an interest thatwouldbefurtheredbyblanketrepresentation.97 As for the third Mathews factor, the risk of an erroneous decision is exceptionally high in light of: the trafficcourtlike haste with which many immigrationproceedingsareheard;thecomplexityofimmigrationlaw;the adversarial nature of the proceedings; and the high evidentiary burden on noncitizens seeking any relief from removal.98 To begin with, unrepresented individuals with severe mental impairments are vulnerable to erroneous decisions in any adjudicatory system because they often cannot understand, formulate, and verbally express ideas in a way that most other people can.99 As the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has explained, [d]isorganized thinking, deficits in sustaining attention and concentration, impaired expressive abilities, anxiety, and other common symptoms of severe mental illnesses can impair the defendantsabilitytoplaythesignificantlyexpandedrolerequiredforself representation even if he can play the lesser role of represented defendant.100 Cognitive limitations pose similar problems. As the Court recognized when it held that the Constitution places a substantive restriction on the States power to take the life of a mentally retarded offender, individuals with cognitive limitations are especially at risk for erroneous factfinding becauseeven with counselthey are less able to presentfavorablefactsandlesspersuasiveaswitnesses.101 Individualswithmentalimpairmentsareparticularlyvulnerableinthe immigrationsystem.Becauseofthevolumeofcasestheyconfront,IJsmust

detainees see the strengthsand weaknessesof their case. See SIULC ET AL., supra note 6, at ivv. This analogy is limited, however, because Legal Orientation Programs are less resource intensive (providing group trainings and only limited individual consultations) and because, in the case of individuals with significant mental disabilities, an appointed representative would need to extensively investigate how that individual might be treated in his country of origin, a process that would limit the degree to which proceedings could be expedited. See infranote158.

97Cf.Indianav.Edwards,554U.S.164,17677(2008)(identifyingthisgovernmentalinterest inthecriminalcontext); AmendedOrderRePlaintiffsMotionfor aPreliminaryInjunction,at 42,FrancoGonzalesv.Holder,No.CV1002211DMG(DTB)(C.D.Cal.2010)(Defendantsdo notdisputethatthepublichasastronginterestinaccurateandfairdeterminationsinremoval proceedings.). 98See e.g., 8 U.S.C. 1158(b)(1)(B)(ii) (2006) (providing that in asylum proceedings immigration judges can require any reasonably available corroboration); In re YB, 21 I & N Dec.1136,1139(B.I.A.1998)(settinghighevidentiaryburden). 99Amended Order Re Plaintiffs Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, at 31, Franco Gonzalesv.Holder,No.CV1002211DMG(DTB)(C.D.Cal.2010). 100Brief for the Am. Psychiatric Assn and Am. Acad. of Psychiatry and the Law as Amici

Curiae in Support of Neither Party at 26, Edwards, 554 U.S. 164 (No. 07208), 2008 WL 405546, quotedinEdwards,554U.S.at176.

101Atkinsv.Virginia,536U.S.304,320(2002).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

391

decide approximately four cases a day,102 roughly twice as many as Social Security Judges.103 (This figure is a low estimate; it does not include other resolutions such as transfers or closures, nor does it account for sick days, vacations, or holidays.) Judges must keep this pace with little assistance; if theyareluckyenoughtobeatacourtwithlawclerks,theygenerallyshare aclerkwiththreeotherjudges.104 Four decisions a day might be feasible if these cases were simple, but they are often highly complex. Immigration law has been described as second only to the Internal Revenue Code in complexity.105 To apply it, one must navigate the fine print of thousands of pages of statutory provisions and regulations, not to mention the several hundred published circuit court decisions that are issued each year.106 Compounding the risk of error, a specialized DHS attorney appears in each of these cases, much like a prosecutor, and advocates the DHSs interest in removing the respondent. This makes it alltooeasy for an unrepresented respondent to be overmatched.107 Finally, respondents who apply for relief from removal bear a highevidentiary burden, one that unrepresented, mentally disabled individualscannotmeetregardlessofthemeritsoftheircases.108 Whenalltheseriskfactorsarecombined,thereisanexceptionallyhigh risk that mentally impaired respondents, if unrepresented, will be erroneously removed. Moreover, such error is essentially final. One relatively lucky family was able to locate a mentally disabled individual incidentally, a U.S. citizenerroneously removed to Mexico,109 but countless others, undoubtedly, have disappeared into their home country withnohopeofreenteringorofreopeningtheircasefromabroad.110

102AM. BAR ASSN, supra note 96, at 216 & nn.12124 (citing EXEC. OFFICE FOR IMMIGRATION

REVIEW, U.S. DEPT OF JUSTICE, FY 2008 STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK, at D1 fig.4 (2009), available at http://www.justice.gov/eoir/statspub/fy09syb.pdf).

103Id.at237&n.304. 104Id.at217. 105CastroORyan v. INS, 847 F.2d 1307, 1312 (9th Cir. 1988) (citing ELIZABETH HULL, WITHOUTJUSTICEFORALL:THECONSTITUTIONALRIGHTSOFALIENS107(1985)). 106 For example, one standard edition of the statute is 1015 pages long. See BENDERS IMMIGRATIONANDNATIONALITY ACTSERVICE(2010ed.)Onestandardeditionofimmigration relatedregulationsis1867pages.SeeBENDERSIMMIGRATIONREGULATIONSSERVICE(2010ed.) 107See Lassiter v. Dept of Soc. Servs., 452 U.S. 18, 28 (1981) (noting that our adversary system presupposes [that] accurate and just results are most likely to be obtained through the equalcontestofopposedinterests). 108Seesupranote98andaccompanyingtext. 109See Problems with ICE Interrogation, Detention, and Removal Procedures: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugees, Border Sec., and Intl Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 110th Cong. 3031 & 67 (2008) (statement of James J. Brosnahan, Senior Partner, Morrison&Foerster,LLP). 1108 C.F.R. 1003.2(d) bars noncitizens from filing motions to reopen after they have been

392

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

Under the logic of the Supreme Courts civil dueprocess jurisprudence,then,thereisastrongargumentforrequiringrepresentation for potentially incompetent noncitizens facing removal. Admittedly, it would be a novel application of Lassiter to hold that a whole class of individuals was entitled to representation, since Lassiter itself applies a casebycase analysis. But this modification makes good sense from a judicial administration perspective: courts do not have the resources to analyze the factual nuances of each of these cases on an underdeveloped record without briefing from counsel or even from a competent litigant. Moreover, although Lassiter prescribes a casebycase form, its analysis could be construed as functionally categorical, singling out various special factors,111 all absent in Lassiters case, that would categorically require counsel. Among the factors that might require counsel, Lassiter mentioned the following: a respondents lack of capacity, the potential for criminal liability, the states introduction of expert witnesses, and particular complexity in the proceedings.112 Even if courts refuse to recognize a categorical right to representation under Lassiter, advocates could still build pressure for reform by making casespecific arguments for representationunderLassiter.113 Providing representation or other protections for mentally ill respondents also makes particular sense because, without these protections, they cannot even access their basic civil procedural rights. At the very least, individuals in removal proceedings have the same procedural rights as any civil litigant. These rights include the constitutional right to examine the evidence against them, to present

physically removed from the United States. Courts are divided on the validity of this regulation. Compare William v. Gonzales, 499 F.3d 329, 332 (4th Cir. 2007) (striking down the regulation), with RosilloPuga v. Holder, 580 F.3d 1147, 1156 (10th Cir. 2009) (upholding regulation). For an indepth analysis of this issue, see Rachel E. Rosenbloom, Will Padilla Reach Across the Border?, 45 NEW ENG. L. REV. 327, 34647 (2011). Nonetheless, even in favorable jurisdictions, it is hard to imagine mentally impaired individuals who will be able, fromabroad,tolocatetheprobonolegalassistancenecessarytoargueagainstthe application of1003.2(d).

111The special factors approach to righttocounsel issues is most often associated with Bettsv.Brady,316U.S.455,46365,473(1942);seealsoinfraPartII.C. 112See Lassiter, 452 U.S. at 3033 (discussing relevant factors and applying these factors to AbbyLassiterscase). 113One advantage to this approach is that advocates could highlight the interests of one smallsubgroupofindividualsremovedwithoutdueprocess:U.S.citizensorindividualswith a colorable claim to citizenship, who arguably have a uniquely compelling right not to be physically removed from the country or stripped of various rights of citizenship (such as the right to work or to travel freely in and out of the country). See DEPORTATION BY DEFAULT, supra note 18, at 45 (noting that [s]ome US citizens with mental disabilities may have been deportedtocountriestheydonotknow,andsomeofthesepeoplehavenotbeenorcannotbe found,andcitingspecificinstances).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

393

evidenceontheirownbehalf,andtocrossexaminewitnessesandevidence put on by the government.114 They have the right to: notice of the removal hearing that is reasonably calculated to reach them;115 be advised of the charged grounds for removal;116 retain counsel;117 and appeal an adverse IJ decision.118 In the criminal context at least, the Court has recognized that procedural rights are only real and adequate if an individual is able to exercise them (in that context, with assistance of counsel).119 Advocates can argue by analogy here: Without special assistance, mentally disabled noncitizens cannot exercise the basic civil procedural rights that the Constitutionprotects. C. DueProcesswithRespecttoMentalIncompetence The third relevant area of law is the constitutional significance of mental incompetence per se, regardless of the nature of the proceedings. The issue of mental disability frequently arose during the Courts gradual leadup to finding a constitutional right to counsel for all state criminal defendants in Gideon v. Wainwright.120 Initially, in Betts v. Brady, the Court rejected such a categorical right, reasoning that indigent state defendants were only entitled to counsel under special circumstances to be identified on a casebycase basis.121 Only gradually, over the next twentyone years, did the Court work its way to an absolute right to counsel in criminal proceedings as it became increasingly clear that there could be no fair trial without counsel, no matter how able or eloquent a defendant might be. [F]eeblemindedness,122 mental illness,123 and limited mental capacity124 were instantly recognized as special factorssome of the most quickly accepted and uncontroversialnecessitating counsel. It is easy to see why: if the system employs a lawyer to present evidence and arguments against the defendant, and the defendant lacks the capacity to understand the evidence against him, to test the validity of that evidence, or to present his own evidence, then there is an unacceptably high risk of

114HernandezGuadarramav.Ashcroft,394F.3d674,681(9thCir.2005)(quoting8U.S.C.

1229a(b)(4)(B)(2000)); see Kaur v. Ashcroft, 388 F.3d 734, 73738 (9th Cir. 2004) (finding a due processviolationwheretheIJfailedtoallowanoncitizentotestifyonherownbehalf).

115Seee.g.,FloresChavezv.Ashcroft,362F.3d1150,1155(9thCir.2004). 116Hirschv.INS,308F.2d562,566(9thCir.1962). 1178U.S.C.1362(2006);RiosBerriosv.INS,776F.2d859,862(9thCir.1985). 118GarciaCortezv.Ashcroft,366F.3d749,753(9thCir.2004). 119SeeCooperv.Oklahoma,517U.S.348,364(1996). 120372U.S.335(1963). 121316U.S.455,473(1942). 122Id.at46364(discussingandquotingPowellv.Alabama,287U.S.45,71(1932)). 123McNealv.Culver,365U.S.109,114(1961). 124Wadev.Mayo,334U.S.672,684(1948).

394

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

wrongful conviction. Or, as the Court stated in Massey v. Moore, [n]o trial can be fair that leaves the defense to a man who is insane, unaided by counsel, and who by reason of his mental condition stands helpless and alonebeforethecourt.125 In a twist on Gideon, the Court recently elaborated on the significance of representation in a decision limiting the right of criminal defendants to appear without counsel. In Indiana v. Edwards,126 the Court held that trial courts may impose counsel on unwilling defendants who are competent to be tried but not competent to present their own defense.127 In so doing, the Court recognized that the interests at stake are not only the defendants interest in a fair trial (which potentially, the defendant may be able to waive),butalsothegovernmentsinterestinpreservingtheintegrityofthe judicial system and the guarantee of fairness that it provides to all individuals, whether or not they ever directly encounter the criminal justice system.128 Arguably, there is a direct analogy to the immigration context.Justasitisessentialtoourselfimageasafreenationtoprotectthe integrity of our criminaljustice system, it is also essential to our selfimage as a nation of immigrants to ensure that our immigration system fairly determineswhocanstayhereandwhomustleave. In the civil context, the Court also has recognized the importance of providingGALsformentallyincompetentlitigants.ItpromulgatedFederal RuleofCivilProcedure17(c),whichinstructscourtstoappointaguardian ad litemor issue another appropriate orderto protect a minor or incompetent person who is unrepresented in an action.129 At least one district court has foundbased on a straight Mathews v. Eldridge analysis with no mention of Lassiterthat mentally incompetent publichousing tenants facing housing court proceedings have a dueprocess right to representation, either by a suitable [volunteer] representative or by an appointedadvocateorguardian.130 In addition to these three lines of cases, there are a few decisions that combine the special status of immigration law with the special circumstances of minor respondents. In these decisions, courts have required the Attorney General to appoint GALs to protect the interests of minors involved in removal proceedingswith glancing reference to the serious interest at stake and to the minors limited capacity, but

125348U.S.105,108(1954). 126554U.S.164(2008). 127Id.at17778. 128Id.at17677. 129FED.R.CIV.P.17(c).Rule17(c),however,reliesontheavailabilityofvolunteerguardians adlitem;thereisnofundingavailabletocompensateguardians. 130Blatchv.Hernandez,360F.Supp.2d595,62122(S.D.N.Y.2005).

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

395

unfortunatelywithoutanalysisorspecificinstructions.131 The three distinct areas of case law outlined above provide strong doctrinal support for the proposition that seriously disabled noncitizens in removal proceedings must be afforded special protections beyond the limited protections already prescribed by the regulations. Removal requires a particularly high level of process because it is akin to, and often worse than, penal incarceration. Even in the civil context generally, due process can require representation, at least on a casebycase basis, when fundamentalinterestsareatstake.Andevenacasebycaseanalysiswould suggest prioritizing representation for particularly vulnerable populations (such as the mentally disabled), just as the Court did, preGideon, when it applied the Fifth Amendment to require counsel for mentally disabled defendantsincriminalproceedings. III. ImaginingPossibleSolutions Having explained the legal arguments why the courts must take affirmative measures to protect the rights of potentially incompetent noncitizens in removal proceedings, I turn next to the practical issue of whatmeasuresmightbefeasibleandadequate. A. Standard(s)forCompetence Before immigration courts can implement any new system, they first needaworkabledefinition(ordefinitions)ofincompetence.Inthecriminal context, a defendant is deemed incompetent to stand trial if he lacks either sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding or a rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him.132 In the civil context, the standard is slightly modified because civil litigants may be unrepresented; courts examine a litigants ability to understand the nature of the proceedings, and (if unrepresented) to present his arguments and defenses and defend his rights.133 In other words, incompetence is a broader concept in the civil context, albeit with less dramatic legal implications in that civil cases can go forward with incompetent litigants as long as they are adequately assisted by counsel, a guardian, or both. In both the criminal and civil contexts, competency combines passive ability (put simply, the

131See, e.g., Johns v. Dept of Justice, 624 F.2d 522, 52324 (5th Cir. 1980) (requiring a GAL andcompilingsupportivecases). 132SeeDuskyv.UnitedStates,362U.S.402,402(1960). 133See,e.g.,UnitedStatesv.30.64AcresofLand,795F.2d796,805(9thCir.1986);Blatch,360 F. Supp. 2d at 62122 (requiring appointment of guardian or representative for unrepresented public housing litigants incapable of present[ing] . . . [their] side of the issue); Bowen v. Rubin,213F.Supp.2d220,223(E.D.N.Y.2001)(findingincompetent underrelevant statelaw civillitigantsincapableofadequatelyprosecutingordefending[their]rights).

396

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

ability to understand what is taking place) and active ability (the ability to participate in the proceedings and to make decisions related to the proceedings). In the context of removal hearings, courts should be instructed to determine whether respondents are capable of presenting arguments and defensesagainstremovalaswellasclaimsforanyavailablerelief.134Courts also must determine whether respondents are capable of consulting with counsel and making decisions. For all impaired respondents, courts will needtoassessothercapacitiesaswell,suchasthecapacitytotestify. B. DutiesoftheDHSandIJstoDeveloptheRecord For mentally impaired individuals to be afforded dueprocess protections in removal proceedings, they first must be recognized as impaired. The DHS, which plays a prosecutorial role in removal proceedings and in many cases has custody over respondents, often has accesstoinformationcallingcompetencyintodoubt,suchasmentalhealth treatment records from a respondents time in custody, or information that a respondent has previously been involuntarily committed or adjudged incompetent in prior criminal proceedings or any other context. By contrast, the respondent himself may not be aware that he suffers from a disability (a common feature of mental illness)135 or that his mental status may entitle him to additional protections. He may well be unrepresented (as in the overwhelming majority of detainee cases), and even if he is represented, his attorney may have highly limited access to him if he is detained. Currently, the DHS denies any obligation to bring information relating to competency to the courts attention.136 The DOJ should promulgate regulations requiring DHS attorneys appearing in its courts to disclose competency facts. Courts have required adversaries to volunteer competencyrelated information in other contexts, such as criminal137 and housingcourtproceedings,138anddueprocessrequiresthesamerulehere.

134Cf. Blatch v. Hernandez, No. 97 Civ. 3918(LTS)(HBP), 2008 WL 4826178, at *4 (S.D.N.Y. 2008) (quoting the settlement of litigation over the rights of mentally disabled publichousing tenants in housingcourt proceedings, which defines an incompetent person as someone who as a result of mental disease or defect . . . is unable to (1) understand the nature of the proceedingsor(2)adequatelyprotectandasserthis/herrightsandinterestsinthetenancy). 135See AM. PSYCHIATRIC ASSN, DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS279(4thed.1994). 136Seesupranote41andaccompanyingtext. 137See United States v. Spagnoulo, 960 F.2d 990, 995 (11th Cir. 1992) (holding that prosecutors Brady obligations include the obligation to disclose evidence bearing on competency). 138See, e.g., Blatch, 360 F. Supp. 2d at 632 (finding that New York City had violated tenants due process rights by failing to notify the housing court of their mental disabilities and

2011

Hearing Difficult Voices

397

At the same time, the DHS may havean institutionalincentive to ignore or downplay evidence bearing on competency (to facilitate removal, simplify the removalproceedings,and avoid the cost of additional treatment). Thus an important component of this duty would be a provision allowing for cases to be reopened where a respondent could present evidence that the DHS had material information concerning competency that it failed to disclose. A further question is what obligation the courts may have to investigate potential incompetence. In the civil context generally, some appellate courts have been reluctant to require that district courts inquire into competency whenever a litigants bizarre behavior raises a substantialquestionastocompetency.139Fearingthatsucharequirement would unduly burden trial courts, one appellate court held that courts need not inquire unless they encounter actual documentation or testimony by a mental health professional, a court of record, or a relevant public agency that a plaintiff might not be competent.140 Such a rule would, however, be harshin cases where an individual is forcedinto court proceedings, where liberty and not merely property is at stake, and where a respondent may well be detained, unrepresented, or unaware of his own condition. Moreover, unlike Article III judges, IJs have a particular duty to develop the record in immigration proceedings under domestic and, in some cases, international law. By statute, the IJ shall administer oaths, receive evidence, and interrogate, examine, and crossexamine the alien andany witnesses.141 In other words, the IJ hasa farmore active role than is customary for adjudicators in the adversarial system. The IJs duty has also been tied to the dueprocess rights of noncitizens appearing in immigration court.142 In asylum proceedings, the United Nations Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status, interpreting international law, states that the duty to ascertain and evaluate all the relevant facts is shared between the applicant and the examiner, and that the adjudicators role is to [e]nsure that the applicant presents his case as

potential incompetence to represent themselves); N.Y. C.P.L.R. 1201 cmt. (McKinney 1997) (Where a party has information indicating that another party is incompetent to protect his interests it should be revealed tothe court so that the court can appoint a guardian. Failure to suggest thepartysinadequacytothe court wouldconstituteafraudwhichcould bethebasis foramotiontosetasideanyjudgment.).

139Ferrelli v. River Manor Health Care Ctr., 323 F.3d 196, 201 (2d Cir. 2003); accord McLean v.CMACMortgageCorp.,398F.Appx467,470(11thCir.2010). 140See Ferrelli, 323 F.3d at 201 n.4; cf. United States v. 30.64 Acres of Land, 795 F.2d 796, 806

(9thCir.1986)(holdingthatitwasanerrornottoconsiderappointingGALwherethelitigant presentedarecordofSocialSecurityAdministrationdisabilityfinding).

1418U.S.C.1229a(b)(1)(2006). 142See,e.g.,Jacintov.INS,208F.3d725,734(9thCir.2000).

398

NewEnglandLawReview

v.45|373

fullyaspossibleandwithallavailableevidence.143 Thus, regulators should require judges to inquire into competency whenever a substantial question (or substantial doubt) exists, even if the only evidence giving rise to that doubt is the respondents own behavior (such as extreme listlessness or apathy, confusion, dissociation, or aggression).Bywayofcomparison:inresponsetosuccessfulconstitutional litigation in the public housing context, the New York City Housing Authority is now required to refer tenants in adversarial proceedings for competency evaluations in a range of scenarios, including if the tenant indicates that he has a mental disease or if [he] has exhibited seriously confused or disordered thinking.144 Where doubt exists as to competency, regulatorsshouldalsorequiretheDHStoproducedetainedrespondentsin court rather than by videoconference so that IJs can directly observe and evaluate their behavior.145 And, if a respondent is found marginally competent, courts must periodically revisit the competency question. As theSupremeCourthasrecognized,mentalillnesscanvaryovertimeand interferes with an individuals functioning at different times in different ways.146 Once the issue of competency is raised, the next question is who assesses it. The DHS already has access to evaluators, particularly in the case of detained respondents whom it may already be treating for mental illness.147 However, given the DHSs clearly conflicting interest,148 the DOJ should maintain its own panel of experts who could address the

143U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status paras. 196, 205(b)(i) (Jan. 1992), quoted in, Jacinto, 208 F.3d at 732 33; accord Agyeman v. INS, 296 F.3d 871, 884 (9th Cir. 2002). Although the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Handbook is not binding on U.S. courts, the Supreme Court has recognized it as persuasive authority because of the UNHCRs role in interpreting the refugee treaty on which U.S. law is based. See INS v. CardozaFonseca, 480 U.S.421,43839&n.22(1987).

T. Drapkin, Protecting the Rights of the Mentally Disabled in Administrative Proceedings,39CATH.LAW.317,347(2000).