Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

ALShumaimeri 2003 Lit Review - From Faculty - Ksu.edu

Hochgeladen von

hoorieOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

ALShumaimeri 2003 Lit Review - From Faculty - Ksu.edu

Hochgeladen von

hoorieCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ch.

3: Review of the related literature

CHAPTER THREE REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE

3.1 INTRODUCTION

This chapter provides the theoretical background of the current study. It contains three main sections. The first section (3.2) presents an overview of the task-based language learning, teaching, and research field. The second section (3.3) explains the relationship between exposure to tasks and motivation by reviewing the related literature. The third (3.4) explains the notion of task-motivation and presents some of the studies conducted to investigate this issue.

3.2

TASK-BASED LANGUAGE LEARNING AND TEACHING

3.2.1 Introduction The use of tasks in language pedagogy has a long tradition, particularly in the communicative approach to language teaching. In fact, in the late 1970s and 1980s, these tasks were often called communicative activities (Crookes, 1986). The term communicative activities has been gradually replaced by tasks (Bygate et al., 2001). The interest in tasks comes from the belief that they are a significant site for learning and teaching (Bygate, 2000: 186). The early research efforts focused on investigating the potential of the task as a unit of organisation in syllabus design or language instruction (e.g., Harper, 1986; Candlin and Murphy, 1987; Prabhu 1987; Breen, 1987, 1989; Long and Crookes, 1993; Willis, 1996 among others). This interest in tasks then shifted to concentrate on the cognitive dimension of the task, and the identification of conditions that affect task performance, in order to inform pedagogy (e.g., Brown and Yule, 1983; Doughty and Pica, 1986; Ellis, 1987; Crookes and Gass, 1993a; Robinson, 1995, 2001; Skehan and Foster, 1997, 1999; Yule, 1997; 34

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

Skehan, 1998; Bygate, 1996, 1999, 2001; Lynch and Maclean, 2000, 2001; Bygate et al., 2001 among others). In this section, a brief summary of task definitions and components is provided in section (3.2.2), and an overview of task-based approaches to syllabus design in (3.2.3). Then, an overview of two approaches to task-based instruction is presented (3.2.4) and some of the contributions to task-based language research are discussed in (3.2.5).

3.2.2

Task definitions

In the literature, numerous definitions of tasks can be found (Breen, 1987; Bygate, 1999; Bygate et al., 2001; Candlin, 1987; Carroll, 1993; Crookes, 1986; Ellis, 2000; Long, 1985; Nunan, 1989; Prabhu, 1987; Richards et al., 1985; Skehan, 1998; Willis, 1996; Wright, 1987; and others). These definitions vary according to the theoretical basis on which they draw. Therefore, it is difficult to find a context-free definition (Bygate, Skehan and Swain, 2001). Two main streams in approaching tasks can be defined here. One is the view of tasks from a pedagogical perspective, i.e. the task as a unit of analysis in syllabus design. The other regards the task as a context for the activation of key processes in language learning (i.e. research-based tasks). The following is a brief summary of some of the definitions found in the literature, in chronological order. For a comprehensive review of task definitions in L2 teaching and research, see, for example Kumaradivelu (1993) and Bygate, Skehan, and Swain (2001). The first definition to appear in the literature is that of Long (1985). Long defines a target task using its everyday nontechnical meaning: A piece of work undertaken for oneself or for others, freely or for some reward. Thus, examples of tasks include painting a face, dressing a child, filling out a form, buying a pair of shoes, making an airline reservation, borrowing a library book, taking a driving test, typing a letter, weighing a patient, sorting letters, taking a hotel reservation, writing a check, finding a street destination and helping someone across a road. In other words, by task is meant the hundred and one things people do in everyday life, at work, at play, and in between. Tasks are the things people will tell you they do if you 35

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

ask them and they are not applied linguists (1985:89).

In this definition, task is broadly defined in plain terms. A task is not necessarily a language learning task for classroom use. For some tasks (e.g. painting a fence), one does not need to use language at all. The emphasis is on the tasks relationship to realworld activities. Crookes (1986) regards a task as: "A piece of work or an activity, usually with a specified objective, undertaken as part of an educational course, at work, or used to elicit data for research" (1986: 1).

Task, once again, is broadly defined. This definition includes different orientations of a task. It encompasses not only pedagogic activities but also job-related work and can be used a means of eliciting data for academic purposes. This definition also emphasises the 'outcome' as an important feature of a task: a ' specified objective'. However, there are more pedagogically oriented definitions of task. Prabhu (1987), for example, defines the 'pedagogical task' as follows: "An activity which required learners to arrive at an outcome from given information through some process of thought, and which allowed teachers to control and regulate that process, was regarded as a task" (1987: 24).

Prabhus definition is oriented towards cognition, process and teacher-fronted pedagogy (Long and Crookes, 1993). The tasks focus upon the learners use and development of their own cognitive abilities through the solution of logical, mathematical, and scientific problems in the target language. Prabhus tasks also focus upon what is to be done in the classroom, and not upon selected language input for learning. The role of the teacher in Prabhu's concept of a task is quite traditional (teacher centred). Prabhu suggests that

36

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

the teacher manipulates the task to control and regulate the learner's cognitive process. Another definition of task with a focus on the language learning process can be found in Breen (1987). Breens focus was and is the learner and learning processes and preferences, not the language or language learning processes (Long and Crookes, 1993). Breen's definition of the task is more oriented to its instructional role, as he defines it as follows: Any structural language learning endeavour which has a particular objective, appropriate content, a specified working procedure, and a range of outcomes for those who undertake the task. Task is therefore assumed to refer to a range of workplans which have the overall purpose of facilitating language learning -from the simple and brief exercise type to more complex and lengthy activities such as group problemsolving or simulations and decision-making (1987c: 23). Breen's definition of task is a broad one, if not the broadest among the various definitions. Its scope allows room for both simple exercises and complex and lengthy activities to be considered as tasks. In addition, a language test can be seen as a type of task, as Breen points out (1987c: 23). This definition demonstrates the instructional focus of Breen's task. Breen sees the task as a workplan, which maps the classroom procedures and arrangement. This definition also reflects a process-based syllabus, which gives more control and involvement to the learners of the task and is concerned also with task design and implementation (see also Candlin, 1987). Another approach to task definition from the perspective of instructional design is Nunan's proposal of what he called 'communicative tasks' tasks that involve communicative language use in which the user's attention is focused on meaning rather than linguistic structure. He defines a communicative task as: A piece of classroom work which involves learners in comprehending, manipulating, producing or interacting in the target language while their attention is principally focused on meaning rather than form (1989: 10). He further argues that the task should have a sense of completeness, being able to stand alone as a communicative act in its own right.

37

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

This definition of communicative task is method-driven, as appears in the key words of the definition, such as comprehension, manipulation, production, interaction and attention to meaning rather than form (Kumaravadivelu, 1993). A key element of the communicative task is the primary focus on meaning, which is an essential characteristic of language learning and teaching tasks. In task-based approaches to language teaching, tasks are explicitly used as units of classroom activity. Two definitions arise here: one given by Willis (1996) and the other provided by Skehan (1998). Willis defines a task as follows: "Tasks are always activities where the target language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose (goal) in order to achieve an outcome" (1996: 23). In this definition, the focus is on achieving an outcome, with the emphasis on meaning, not language. There is also clear indication of the learners role in using the language in a meaningful way to reach an outcome. There is another definition of the task in task-based approaches to language teaching. Skehan (1998) gives a useful definition of tasks within task-based instruction: "A task is an activity in which: - meaning is primary - there is some communication problem to solve - there is some sort of relationship to comparable real-world activities - task completion has some priority - the assessment of the task is in terms of outcome" (1998: 95).

This definition incorporates most of the task features included in other definitions (Bygate et al., 2001). It emphasises meaning-oriented, problem-solving activities which have a real-world relationship. Learner performance is assessed in terms of task completion. This implies that the completeness of a task performed by the learner, not

38

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

the quality of the learner's language per se, will be a major factor in assessing learner performance of a particular task. By this definition, Skehan rules out 'an activity that focuses on language itself' such as a transformation drill, or the consciousness-raising tasks described by Ellis (1997), and many of the tasks in Nunan (1989, 1996) which fall within the categories of tasks that Skehan describes as 'structure-trapping' (Robinson 1998, 2000). From a research-based perspective, Bygate (1999b) offers a useful definition, which is followed in this study as a working definition of task design, as he defines tasks as: "Bounded classroom activities in which learners use language communicatively to achieve an outcome, with the overall purpose of learning language" (1999b: 186).

By bounded is meant that the activities have a starting point, which is the input and an end, which is the outcome. The 'outcome' can be interpreted here as the purpose of the task, which is using the language communicatively. It can also be interpreted as the goal of the task, in terms of either task completion or promoting learners' language development. This broad definition is inclusive of most task characteristics with an emphasis on language development. Finally, Bygate, Skehan, and Swain (2001) propose a series of definitions of tasks with different emphases, which reflect the different uses of the task. They explain that "definitions of task will need to be different for the different purposes to which tasks are used" (Bygate et al., 2001: 11). They first offer a 'basic, all-purpose definition': "A task is an activity which requires learners to use language, with emphasis on meaning, to attain an objective" (2001: 11).

Then, using a framework which Bygate et al. (2001) refer to as a "manner of working with tasks (pragmatic vs. research) and user groups and contexts (teachers, learners, assessment)," they provide six definitions to reflect the different purposes of tasks. For 39

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

example, if the focus is on the learners and learning in the context of 'research', they suggest the following definition: "A task is a focused, well-defined activity, relatable to learner choice or to learning processes, which requires learners to use language, with emphasis on meaning, to attain an objective, and which elicits data which may be the basis for research" (2001: 12).

To summarise, we have seen that various types of definitions of task have been offered, serving different purposes. Drawing on the main features of these definitions, a wellinformed and widely applicable perspective of the concept of task can be obtained, which will aid in understanding this study and the various studies conducted using tasks, some of which will be introduced in the following sections. In the following paragraphs, key elements of a task that arise from the definitions above are presented.

3.2.2.1

Task features

This section provides a brief overview of the key elements that the above definitions have addressed. A set of task features can be identified as follows: Where, (a) Objectives or goals concern the intentions behind performing any task. These goals might be learning goals, such as developing learners skills, or they might Objective (Goal). Input Data. Procedures. Learner Role. Teacher Role. Setting. Real-World Relationship.

40

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

be learners' goals that vary in orientation between 'achievement orientation' and 'survival orientation', as Breen (1987c) has suggested. The objective may be interpreted as the task outcome; several definitions assert that tasks should have a clear outcome. The task outcome may also be interpreted as using the language. Task completion is considered to be a task objective according to Prabhu (1987). However, a distinction should be made between a task outcome and its goal. The goal of the task should address the pedagogical purpose of the task, e.g. development of speaking skills, whereas the outcome should address the specific result of a given task, e.g. describing the way to the library successfully. (b) Input data concern materials used and information given to be used as material. They can be given either in linguistic, oral or written, or non-linguistic form. Examples of input data are texts, newspaper extracts, photographs, and audio and video recordings. (c) Procedures concern the step-by-step procedures to be followed in order to complete a task. These include the way the input data are presented, the type of task, and task complexity. (d) Learner role refers to the role of the learner implied by the task, from being receptive to an active role where he makes decisions regarding his learning and learning activities. Approaches differ as to the roles that learners play in a taskbased approach. The learners' role is closely related to the teachers role, as there is some exchange of roles between them. (e) Teacher role concerns the role of the teacher implied by the task, which differs according to the task orientation and goal, from full control of the learning process to only being an observer of this process. There might be an agreement

41

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

among researchers that the teacher using a task-based approach needs to be more skilled than teachers using traditional approaches (Skehan, 1996). (f) Setting concerns the environment in which the task is to be implemented; this could be the classroom or somewhere outside it. It also concerns the nature of performance required for the task to be undertaken, such as individual work, group work and pair work. (g) Real-World relationship concerns the tasks resemblance to real-world activities outside the classroom. Some tasks, such as those of Long (1985) are real-world activities, e.g. painting a fence, giving a street direction, borrowing a library book. Other tasks, on the other hand, may not have such close relationship to real-world activities, but still have value as pedagogic tasks for classroom use, e.g. spot the difference, telling a story based on pictures, describing a picture for someone to draw, drawing a route on a map and others. Having some sort of relationship to real-world activities (Skehan, 1996) may be the middle ground among the different approaches to identifying tasks.

These are the main features of a task or task components. Their identification helps task designers and researchers to address different issues. This list will be of help in this study as a framework for the design of the 24 tasks and in building the theoretical background of the aspects of tasks that motivate learners. Next, task-based syllabuses and approaches to language teaching are presented.

3.2.3

Task-based syllabuses

In the previous section, it was shown that different definitions of task exist according to the context and the theoretical basis on which they are constructed. In this section, the focus will be on the task-based approaches to syllabus design and language teaching, 42

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

which take the task as a central element around which syllabus content is organised. Syllabus design is thought to be based essentially on a decision about the 'units' of classroom activity, and the sequence in which they are to be performed (Robinson, 1998). Various types of approaches to syllabus design have employed different units; there are structural, functional and notional, skills, communicative, and task-based syllabuses. However, there have been continuous attempts to categorise them into two main strands, synthetic versus analytic (Wilkins, 1976; White, 1988; Long and Crookes, 1992, 1993). A brief overview of these two types of syllabuses is presented in section 3.2.3.1. Other research has been directed to investigate the potential of the task as a unit of organisation in syllabus design or language instruction (e.g., Candlin and Murphy, 1987; Prabhu 1987; Breen, 1987, 1989; Harper, 1986; Long and Crookes, 1993; Willis, 1996). Studies of this type are discussed in section 3.2.3.2.

3.2.3.1

Synthetic vs. Analytic syllabuses

Wilkins (1976) made the classic distinction between synthetic and analytic syllabuses in the language classroom. Synthetic syllabuses, similar to type A syllabuses in White (1988), segment the target language into discrete linguistic items for presentation one at a time: Different parts of language are taught separately and step by step so that acquisition is a process of gradual accumulation of parts until the whole structure of language has been built upAt any one time the learner is being exposed to a deliberately limited sample of language. The language that is mastered in one unit of learning is added to that which has been acquired in the preceding units. (Wilkins, 1976: 2). The language learning process is seen as the steady accumulation of linguistic rules and items, in the ultimate direction of command of the second language. It is assumed that the learner is able to learn language in parts, and to integrate them when the time comes to use them for communicative purposes. Wilkins (1976) indicated that 43

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

the learners role is to re-synthesise the language that has been broken down into a large number of small pieces with the aim of making his learning task easier. Synthetic approaches to syllabus design characterise many traditional or conventional language courses and textbooks. The actual units according to which synthetic syllabuses are organised vary. Structural, lexical, notional and functional, and most situational and topical syllabuses are all synthetic (Long and Crookes, 1992, 1993; Long and Robinson, 1998). Synthetic syllabuses, also called "focus on forms" in Long and Robinson (1998), however, have been criticised for major problems, which include: (a) absence of needs analysis; (b) linguistic grading; (c) lack of support from language learning theory; (d) ignorance of learners' role in language development; (e) tendency to produce boring lessons, despite the best efforts of highly skilled teachers and textbook writers; and (f) production of many more false beginners than finishers (see Long and Robinson 1998 for more detail). The second fundamental type of syllabus distinguished by Wilkins is the analytic. In analytic syllabuses, the prior analysis of the total language system into discrete pieces of language that is a necessary precondition for the adoption of a synthetic approach is largely superfluous Analytic approaches are organised in terms of the purposes for which people are learning language and the kinds of language performance that are necessary to meet those purposes (Wilkins, 1976:13). Here a chunk of language is presented to the learner in the context of a meaning oriented lesson. Analytic refers not to what the syllabus designer does, but to the operations required of the learner to recognise and analyse the linguistic components of the language chunks presented. Long and Crookes (1993: 11) update Wilkins definition, pointing out that analytic syllabuses are those that present the target language whole chunks at a time, in molar

44

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

rather than molecular units, without linguistic interference or control. They rely on (a) the learners presumed ability to perceive regularities in the input and induce rules, and/or (b) the continued availability to learners of innate knowledge of linguistic universals and the ways language can vary, knowledge which can be reactivated by exposure to natural samples of the L2. Procedural, process, and task syllabuses are examples of the analytic syllabus type. In the next section, a brief account of examples of analytic syllabuses, namely, Prabhu (1987); Breen (1987); Breen and Candlin (1984, 1987); Harper (1986); Long (1985, 1998); Long and Crookes (1992, 1993) will be presented. Although arguably "more sensitive to SLA processes and learner variable" than synthetic syllabuses (Robinson, 1998), some types of analytic syllabuses, also called "focus on meaning" in Long and Robinson (1998), have been criticised for, for example, lack of needs analysis, lack of accuracy attained, unlearnability of some grammatical features from positive evidence only, and deprivation of the opportunity to speed up the rate of learning.

3.2.3.2

Task-based syllabus design

According to Long and Crookes (1993), most analytic approaches to syllabus design take the task as the unit of analysis. However, as seen above, definitions of tasks have varied according to the theoretical basis on which they draw. Four approaches to syllabus design are presented next, starting with the procedural syllabus. The procedural syllabus is strongly associated with the work of Prabhu (1984, 1987) in the Bangalore Communicational Teaching Project in India (for evaluation of the Bangalore Project see Beretta, 1989, 1990; Beretta and Davies, 1985; Brumfit, 1984; Long and Crookes, 1992, 1993). Prabhu maintains that the acquisition of linguistic 45

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

items is not a single uncomplicated step from zero knowledge to target mastery. Instead, there is a realisation implicit in procedural syllabuses that linguistic items are acquired subconsciously through the operation of some internal system of abstract rules and principles (Prabhu, 1987: 70) while the learner is focused wholly on meaning. The role of the teacher in Prabhu's procedural syllabus is quite traditional; classes are "teacher centred", and group work is discouraged "because of the fear that learner-learner interaction will promote fossilisation" (Prabhu, 1987: 82). Prabhus pedagogic proposals are strikingly similar to those of the Natural Approach (Krashen and Terrell, 1983). Prabhus characterisation of the procedural syllabus constitutes a fairly radical departure from previous thinking (synthetic syllabuses). In contrast to other forms of communicative language teaching, which teach towards a goal of being able to use the language communicatively, the Bangalore project teaches the language through communication, as Prabhu points out: Communicative teaching in most Western thinking has been training for communication, which I claim involves one in some way or other in preselection; it is a kind of matching of notion and form. Whereas the Bangalore Project is teaching through communication; and therefore the very notion of communication is different (1987: 164). Prabhu's proposal was concerned with the language learning tasks that form the basis of classroom activities for teachers and students. The task should be one which learners perceive as a reasonable challenge, that is a problem which poses difficulty while at the same time being feasible. These tasks may be unrelated to communicative performance in the outside world (Kumaravadivelu, 1993). In contrast to Prabhu's teacher-centred approach, Breen and Candlin (1984) argue instead for a different interpretation of an analytic syllabus. They refer to this as a process syllabus. Breen and Candlin's focus was and is on the learner and learning

46

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

processes and preferences, not the language or language-learning processes (Long and Crookes, 1993). Candlin argues that "targets for language learning are all too frequently set up externally to learners with little reference to the value of such targets in the general educational development of the learner" (1987: 16-17). Instead, Breen and Candlins process syllabus is the subject of continual negotiation and re-interpretation between students and teacher. As Breen (1984) notes, "A Process Syllabus addresses the overall question: Who does what with whom, on what subject-matter, with what resources, when, how, and for what learning purpose(s)? Breen seeks to avoid any prespecification of syllabus content. According to Foley (1990), the process syllabus offers a bridge between content and methodology. It suggests a framework which allows the teacher and the learners to create their own syllabus in an ongoing and adaptive way. In other words, this framework radically gives learners control over choice of materials (tasks) and their use through 'procedural negotiation' aiming at achieving agreement between the classroom participants (learners and the teacher) as to the content, methodology and evaluation of the teaching (Breen, 1987; Breen and Littlejohn, 2000). The proposal of the process syllabus, however, lacks clear theoretical bases to support it. There is little reference to the language learning literature or SLA research; rather it is based on the intuitive ideas of Breen and Candlin (1987) and Breen (1984, 1987a, 1987b, 1987c). Candlin (2001) admits that his early work was speculative, although he asserts its importance for the development of the field, and suggest that speculation should continue beyond the exploratory phase of an endeavour, if only to check our compasses, as it were, and resight some of our objectives" (2001: 230). From a different perspective, Harper and his team at the English Language Centre (ELC) at King AbdulAziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Harper, 1986; Wilson, 1986) propose a task-based syllabus. In the ELC, they carry out ESP courses (such as

47

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

English for medical students) for students at the tertiary level. The students are required to study all or part of their chosen discipline in the medium of English (Wilson 1986). Learning English for its own sake is assumed not to be the students educational purpose. The ELC programme is based on the premise of learning by doing, that is, the more one does something, the better one gets at doing it. The task was chosen to be the unit of the ELC courses, which are based on behavioural objectives set by the faculties the students will be joining. According to these objectives the ELC staff design the bandsheets which are used as criteria for the assessment of student proficiency, and also for grading and sequencing the tasks. The bandsheet consists of nine bands; from band one for a student who is only just beginning to acquire English language skills, to band nine for a student who has achieved a native-like proficiency. It has been suggested that the principles of task-based learning can be most effective only when it is applied within the range of band three to band seven. Students below level three must follow a special foundation programme, where tasks are not employed. However, despite being interesting and innovative, the ELC programme has many problems. Firstly, it has not been thoroughly based on theories of learning. Another problem is connected with the grading of task difficulty; as Wilson (1986: 17) points out, No formula has yet been found which can be applied to all tasks in order to rate difficulty. Therefore, a process of fine tuning is necessary throughout the course. In addition, there is much resemblance to type A syllabuses in some key issues. The fourth approach to course design is task-based language teaching developed by Long (1985, 1991, 1998; Long and Crookes, 1992, 1993). Unlike the above three proposals, Long approaches tasks from a psycholinguistic perspective based on SLA research. The theoretical basis underlying Longs approach to task-based learning is his Interaction Hypothesis, which was prominent in research in the 1980s and continues to

48

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

attract attention, as Ellis (2000) points out. In its early form (Long 1983), the Interaction Hypothesis claimed that acquisition is facilitated when learners obtain comprehensible input as a result of the opportunity to negotiate meaning when communication breakdown occurs. In its later form (Long 1996), the theory has been extended to take account of other ways in which meaning negotiation can contribute to L2 acquisition, namely through the feedback that learners receive on their own productions when they attempt to communicate and through the modified output that arises when learners are pushed to reformulate their productions to make them comprehensible. In the later version, then, meaning negotiation serves to draw learners attention to linguistic form in the context of a primary focus-on-meaning. This is what Long (1991, 1997) calls focus on form. Focus on form, according to Long (1997), refers to how attentional resources are allocated, and involves briefly drawing the students attention to linguistic elements (words, collocations, grammatical structures, and so on), in context, as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning, or communication, the temporary shifts in focal attention being triggered by students comprehension or production problems. Long (1997) argues that focus on form is learner-centred in a radical, psycholinguistic sense: it respects the learners internal syllabus. It is under the learners control as it occurs just when a learner has a communication problem, and so is likely already at least partially to understand the meaning or function of the new form, and when a learner is attending to input. Doughty and Williams (1998: 04) point out that it should be kept in mind that the fundamental assumption of focus-on-form instruction is that meaning and use must already be evident to the learner at the time that attention is drawn to the linguistic apparatus needed to get the meaning across. As seen above in his definition, Long (1985) distinguishes between target tasks and pedagogic tasks. He (Long & Crookes, 1993) argues that identifying target tasks by

49

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

carrying out a needs analysis would help in identifying the task types relevant to learners. Then, the pedagogical tasks are derived from the target task types. These pedagogic tasks are then sequenced to form a task-based syllabus, which in turn is implemented with appropriate methodology and pedagogy, e.g., focus on form. It is the pedagogical task, as Long (1993) points out, that teachers and learners work on in the classroom. This framework may be appropriate for specific purposes courses, such as the ones at the ELC explained above. However, task-based syllabuses have been criticised by many scholars, on a variety of grounds (Bygate, 2000; Kumaravadivelu, 1994; Robinson, 1998; Sheen, 1994; Skehan, 1998). Apart from Long's work, many proposals have been little informed by theories of learning (Bygate, 2000). They are based on theoretical arguments, rather than on empirical evidence of effectiveness (Sheen, 1994). Skehan (1998) criticises their failure to recognise individual needs, individual differences, and learning styles. However, although these task-based syllabuses were less informed by theories of learning and "were not proposed in the light of systematic evaluative research" (Bygate, 2000: 187), they shed light on the potential of pedagogic tasks. Pica (1997, cited in Ellis, 2000) asserts that task is seen as a construct of equal importance to second language acquisition (SLA) researchers and to language teachers. Therefore, tasks have been evaluated as contexts for the activation of key processes of second language learning and use (Bygate, 2000). In addition, researchers have investigated the effects of tasks on learners and their relationships to second language acquisition and learning (Brown and Yule, 1983; Bygate, 1996; Skehan, 1998; Ellis, 1999; Robinson, 1995; Yule, 1997). In addition, within a post-method condition (Kumaravadivelu, 1994), the use of tasks has been strengthened and broadened throughout the study of language teaching and pedagogy. Bygate (2000) points out that interest has shifted away from a principal

50

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

concern with the packaging of teaching approaches towards understanding the repertoires of different kinds of tasks available to teachers and learners. The interest in tasks has grown immensely, leading to their use in other fields such as teacher development (Cameron, 1997). Before looking at some of the efforts in task-based research, this section presents two task-based instruction models, those of Willis (1996) and Skehan (1996, 1998).

3.2.4 Task-based instruction This section reviews some examples of the efforts to provide teachers and syllabus designers with a methodological framework that uses pedagogic tasks as its principal components. As an alternative to PPP (the traditional approach to language teaching: presentation, practice, and production), different approaches to using tasks have been proposed in the literature (Fotos and Ellis, 1991; Loschky and Bley-Vroman, 1993; Willis, 1993; Skehan, 1996, 1998; Willis, 1996; Long, 1998; Long and Robinson, 1998 among others). Long and Crookes (1991) provide a rationale for using tasks in instruction. They propose that what is important is that instruction (a) enables acquisitional processes to operate, particularly by allowing meaning to be negotiated, and (b) maintains a focus on meaning, as opposed to a focus on form. In this brief review, two approaches are described, those developed by Willis (1996) and Skehan (1998). Willis (1996) was inspired by the work of Prabhu (1987) and claimed to be supported by some of the findings in the field of second language acquisition (SLA). However, Skehan (1998) criticises Williss work for not being connected effectively with theory about second language acquisition such as the role of noticing, acquisitional sequences, and information processing. Critics also indicate that the framework is not based on or

51

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

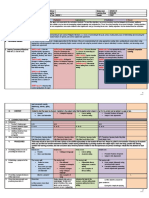

connected to systematic evaluative research (Bygate, 2000). On the other hand, Skehan, from a psycholinguistic perspective, proposes a cognitive, information processing model for task-based instruction grounded in theory and research. Table 3.1.1 presents the principles of both approaches, which inform the design and implementation of a task-based approach.

TABLE 3.1.1: PRINCIPLES OF TASK-BASED INSTRUCTION FROM WILLIS (1996) AND SKEHAN (1998).

WILLIS 1996 1. THERE SHOULD BE EXPOSURE TO WORTHWHILE AND AUTHENTIC LANGUAGE. 2. THERE SHOULD BE USE OF LANGUAGE. SKEHAN 1998 1. CHOOSE A RANGE OF TARGET STRUCTURES. 2. CHOOSE TASKS WHICH MEET THE UTILITY CRITERION IDENTIFIED BY LOCHKY AND BLEY-VROMAN (1993). 3. SELECT AND SEQUENCE TASKS TO ACHIEVE BALANCED GOAL DEVELOPMENT. 4. MAXIMISE THE CHANCES OF A FOCUS ON FORM THROUGH ATTENTIONAL MANIPULATION. 5. USE CYCLES OF ACCOUNTABILITY.

3. TASKS SHOULD MOTIVATE LEARNERS TO ENGAGE IN LANGUAGE USE. 4. THERE SHOULD BE A FOCUS ON LANGUAGE AT SOME POINTS IN A TASK CYCLE. 5. THE FOCUS ON LANGUAGE SHOULD BE MORE OR LESS PROMINENT AT DIFFERENT TIMES.

It can be seen above that both concentrate on the design and procedures of using tasks in the framework. Both also consider focus on language form at some points of the framework to be essential. However, it appears that focus on a balanced development of learners language in terms of accuracy, complexity and fluency dominates Skehans proposal. Skehan starts by identifying a range of target structures to ensure systematicity in language development by keeping track of interlanguage development without falling into a structural method. Then, tasks should avoid what he terms structure trapping by following the utility criterion; that is, it should be useful for learners to perform the target structures, although they are not forced to do so. Principle 3 concerns keeping a balance of focus on fluency, accuracy and complexity through the task framework. The fourth principle concerns the channelling of learners attention to focus on form through the stages of the framework. The last principle concerns

52

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

mobilising students metacognitive resources to keep track of what has been learned through evaluation processes. However, Willis emphasises that tasks should be motivating to the learners and that tasks need to meet some criterion of engagement to be considered worthwhile (Skehan, 1998). Willis points out that motivation is an important condition for language learning to occur. She suggests that learners need motivation for learning; that is, motivation to process the exposure they receive, and motivation to use the target language in order to benefit from exposure and use (Willis, 1996: 14). This point is of interest to this study, as it sheds light on the relationship between tasks and motivation, which will be discussed further later in this chapter (see section 3.3, p.63). Task-based approaches to language teaching all seem to have proposed a model comprising three phases for implementing a task-based lesson, although they differ in the detailed procedures followed in each phase. The first phase is the pre-task phase, which concerns the activities carried out prior to the performance of the actual task, as an introductory or preparation phase. The second is the during-task phase, which concerns the actual performance of the task and may involve other procedures, as will be seen below. The third is the post-task phase, which concerns the activities carried out after the completion of the task. Table 3.1.2 below presents the procedures to be followed in each stage, as proposed by Willis (1996) and Skehan (1998).

53

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

TABLE 3.1.2: SUMMARY OF TASK-BASED FRAMEWORK FROM WILLIS (1996) AND SKEHAN (1998).

TASK PHASE PRE-TASK WILLIS 1996 -exploring the topic with the students to raise the schematic knowledge of it, and to provide a reason for real communication. -Providing a model of similar task to make the language available so noticing can occur (Schmidt, 1990). -brainstorming and mind maps activities SKEHAN 1998 Use of pre-task activities may include providing a model to introduce, mobilise, recycle language, to ease processing load (content focus), and to push learners to try new forms of language (Sato, 1988; Chafe, 1994). Planning: guided with language or content focus, or no planning (Foster and Skehan, 1996; Skehan and Foster, 1997). A number of options, which may influence attentional availability: Time pressure: the speed with which a task needs to be completed (time limit or no time limit) (Yuan and Ellis, 2003). Support: whether to allow students access to the input data while performing the task (Robinson, 1995; Brown et al, 1984; Skehan and Foster, 1997) structured task. Surprise: introducing some surprise element into the task (Foster and Skehan, 1997). Control: giving learners opportunity to choose the way they like to do the task (Kumaravadivelu, 1993; Breen, 1987). Altering attentional balance through post-task activities such as public performance (Samuda et al, 1996), analysing task performance (Lynch, 1998). Reflection and Consolidation: to encourage learners to restructure, and to use the task and its performance as input to help in the process of noticing the gap and to develop language(Willis and Willis, 1996; Johns, 1991). Cycles of task-based activities: repetition (Bygate, 1996, 1999; Lynch and Maclean, 2000, 2001).

DURING TASK

Called task cycle and includes three stages: Task: students perform the task and teacher monitors from a distance. Planning: students prepare to report to the whole class how the did the task (includes rehearsal of public performance). Teacher helps with the language. Report: some groups reports publicly to whole class and results are compared.

POST-TASK

Called language focus: includes consciousness-raising activities and practiceoriented work of words, structures, functions required for a communicative purpose and relevant to learners.

The table presents a brief outline of the main procedures followed in each of the frameworks. It is not the aim here to review the frameworks in detail, but to highlight some of the comparable and interesting points found in them. First of all, the two frameworks seem to agree on the importance of pre-task activities that provide learners with exposure to actual language samples, so as to provide opportunities for a focus on form to be set in motion, and for noticing to occur (Skehan, 1998: 127). Skehan (1998) seems to push this further by an intentional focus on form and by indicating that the pretask activities are important in order to introduce new language, to increase the chances that restructuring will occur in the underlying system, to mobilise language, to recycle

54

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

language, and to push learners to interpret tasks in more demanding ways. All these reasons put forward by Skehan (1998) are primarily concerned with language. The second example of similarity of procedures between the two frameworks is the use of public performance after task completion and the language focus that underlies this option. Willis (1996) includes public performance in the last stage of the during task phase of her framework. The public performance provides an opportunity to focus on form and displays the language focused on in the previous stage of planning the report. Skehan (1998) considers public performance to be an option for post-task activities, which may provide an opportunity to alter learners attention to a greater focus on accuracy. However, Skehan (1998) is cautious in regard to this option as it needs further research. However, the two frameworks differ strikingly in the way focus on form is allocated. Skehan, from a psycholinguistic perspective, tries to address the aim of a balanced focus on form and meaning in his model, to ensure a balanced development of fluency, accuracy and complexity and to ensure longer-term language development. It can be seen in his model that focus on form is seized throughout the three phases of the framework. Willis (1996) recognises the importance of focus on language by allocating the third phase of her task-based framework to focus on language form. The focus is either through language focus analysis using consciousness-raising activities, students analysis of texts, or through explicit form-focused practice of words, phrases, patterns and sentences from the analysis activities, relevant to learners and required for a communicative purpose. Overall then, the two frameworks share some qualities but are different in the procedures followed. Williss framework is well structured, systematic and consistent, with some links to SLA research. The second framework (Skehan, 1998) is a framework

55

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

well-informed by theory and empirical research findings and open to further options. However, neither has been subject to systematic evaluative research.

3.2.5 Task-based language research In task-based research, tasks have been used as basic conceptual units to analyse learning behaviours that lead to second language acquisition (Drnyei and Kormos, 2000: 275). The task can be broken down and analysed, which makes it easier to investigate. For example, some studies investigated some task design variables in relation to language production such as input (e.g. Brown et al., 1984; Berwick, 1993; Robinson, 1995; Swain and Lapkin, 2001), task conditions (e.g. Long, 1989; Newton and Kennedy, 1996; Robinson, 2001), and task outcomes (e.g. Duff, 1986, Brown, 1991; Pica et al., 1993; Bygate, 1999b, Skehan and Foster, 1999). Others have investigated task methodology variables in relation to language production such as planning (e.g. Ellis, 1987; Crookes, 1989, Foster and Skehan, 1996, 1999; Skehan and Foster, 1997, Wendel, 1997; Wigglesworth, 1997, 2001; Yuan and Ellis, 2003), and task repetition (e.g. Bygate, 1996, 2001; Gass et al., 1999; Lynch and Maclean, 2000, 2001). The latter two strands of research focus will be presented as examples of task-based research efforts.

3.2.5.1

Research on the effect of planning on language performance

This section presents an overview of some investigations of the effects of planning on the language performance of language learners as a possible condition of task performance. It reviews previous studies (Crookes, 1989; Foster, 1996, 2001; Foster and Skehan, 1996, 1999; Skehan and Foster, 1997; Wigglesworth, 1997, 2001; Yuan and Ellis, 2003) considering results and research procedure. Crookes (1989) investigated the nature of interlanguage produced by EFL learners who

56

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

performed two tasks with and without planning. The results showed that planning time affected variety of lexis (but not syntax) and complexity of language. On the other hand, planning time did not have a significant effect on accuracy, except for the significant effect on target language use of the (article). Based on the criticisms of the studies of Ellis (1987) and Crookes (1989), Foster and Skehan (1996) and Skehan and Foster (1997) researched the effect of planning time on students oral language performance. They carried out more comprehensive studies by implementing tasks which EFL teachers could use in the classrooms, such as personal, narrative and decision-making tasks, and data were collected during their normal class schedules (Foster, 1996). Their studies also considered the familiarity and cognitive load of the task in relation to planning time in greater detail than any other studies. Nevertheless, these were not investigated in a single task. The personal task (Foster and Skehan, 1996) and the narrative task (Skehan and Foster, 1997) were considered to make use of familiar information, while the narrative (Foster and Skehan, 1996) and decision-making tasks (Skehan and Foster, 1997) were considered less familiar tasks. The following results were found from their studies. Firstly, without planning, there was a relatively even level of performance across the task. On the other hand, planning led to much greater fluency, complexity and accuracy. Secondly, planning resulted in trade off effects on task performance. Lastly, the effects of planning were different, depending on task type. Greater complexity was gained in the narrative task (Foster and Skehan, 1996) and the decision-making task (Skehan and Foster, 1997) than in the personal information exchange task. These two tasks also showed a stronger effect on fluency than did the personal task. It is possible that since the personal information exchange task included familiar and ready-encoded information, it demanded less cognitive processing. Therefore, the effect of planning time may be stronger with more

57

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

difficult tasks requiring more cognitive processing. Wigglesworth (1997) also obtained similar findings to those of Foster and Skehan in a test situation. She found tentative support for the hypothesis that planners are more fluent in a testing situation, although the planning time allowed in this study was only one minute. This planning time led to more complex and accurate language use in the case of the high proficiency learners on the more difficult tasks. In another study, Wigglesworth (2001) investigated the effect of a number of test task variables, one of which was planning, on adult ESL learners performance on five tasks that were routinely used to evaluate achievement in the Australian Adult Migrant Education Programme. In this study, the results for planning were inconsistent with the previous studys findings, as there was no planning effect on accuracy. Wigglesworth (2001) attributed this to the differences in the evaluation measures, as she used external ratings to assess the material rather than analytic measures such as error-free clauses. Foster and Skehan (1999), continuing their investigation of the effect of planning as it relates to language performance, examined different sources of planning and different foci of planning, in an effort to determine best practices for pedagogical purposes. The study involved four groups of learners working on the same task. Source variables were the teacher, the group, solitary planning and no planning at all. Focus variables were focus on form, focus on meaning, and no planning. The no planning and solitary planning groups were established to provide a control group and to allow for comparison to previous studies, since the majority of planning studies have involved solitary planning. The results showed no significant differences in fluency between the groups. However, both complexity and accuracy measures reflected differences in regard to the source variables. Most interesting was the accuracy measure, where scores were much higher

58

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

in the teacher-led planning condition. The solitary planning group showed more complex and more fluent language, whereas the group-based planning group produced less fluent language. The no planning group, other than lacking complexity, did not differ significantly from the others. In regard to the focus of planning condition, the form vs. meaning planning conditions had no differential effect on performance. In conclusion, Foster and Skehan (1999) argued that teacher-based planning provided the most balanced performance, because it produced the greatest accuracy gains without compromising fluency and complexity. They proposed that the role of the teacher in pre-task work can make an important pedagogical contribution. In a rather different approach to investigating planning effect on language performance, Yuan and Ellis (2003), in a study based on Elliss (1987) work, explored and compared the effects of on-line planning and pre-task planning on fluency, accuracy, and complexity of language production. The study consisted of a single task (narrative task) performed by different groups under three different planning conditions (pre-task, online, no planning). In the pre-task planning group, learners were given ten minutes to plan for task performance and then performed the task under time pressure. In the online planning group, the learners were given no chance to plan before task performance, but they were allowed unlimited time to perform the task. The control group (no planning condition) had no pre-task planning time and was required to perform the task under time pressure. The results showed that the pre-task planning group achieved greater fluency than the on-line planning group. In regard to complexity, both pre-task planning and on-line planning appeared to have a positive impact on grammatical complexity. The results for accuracy were compelling; accuracy increased in direct proportion to planning time, as the on-line planning group showed greater accuracy than the pre-task planning group.

59

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

The control group scored lower than the other groups on all measures. Examination of the on-line planning condition showed that the on-line planners spent more planning time than did the pre-task group. The pre-task group produced more speech, but the online group produced more accurate speech. The on-line group utilised more reformulations and self-corrections, slowing down speech rate but improving output, and this is evidence of self-monitoring during a task. Yuan and Ellis (2003) remained cautious as they indicated that the study represented only one very limited learning context, and that more research into on-line planning is needed. Overall, the evidence of the studies reviewed in this section suggests that planning has a significant effect in improving fluency and complexity, but does not have a consistently significant effect on accuracy, across the different planning conditions and task types. These results have potential pedagogical implications that planning conditions can be varied depending on whether fluency, complexity or accuracy is the target aspect of language performance.

3.2.5.2

Effect of task repetition on language performance

This section presents an overview of some of the studies that have investigated the effects of task repetition on language performance (Bygate, 1996, 2001; Gass et al., 1999; and Lynch and Maclean, 2000, 2001). The reviews consider research methodology and results. Bygate (1996) examined the effect of task repetition on the language produced by one learner narrating a video extract (a Tom and Jerry cartoon) on two separate occasions immediately after viewing it. The two occasions were three days apart, and the learner had no prior warning or indication that the task was going to be repeated. In a qualitative analysis, the results showed that task repetition had a strong effect on complexity. 60

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

More specifically, the results for the repeated task were the following: lexical and grammatical selection improved; there were fewer errors; more complex grammartical structures were used; the range of vocabulary items was wider; the earlier oddness of lexical selection was reduced and the subjects speech became more native-like in the repeated task; self-correcting repetitions were more frequent. The use of regular verbs increased over irregular verbs; and the simple past tense was used more. The overall performance in the repeated task was better than the first performance in terms of accuracy, repertoire and fluency. The results suggest that repetition of tasks enables learners to improve their formulation, just as varying planning time can also affect performance (Bygate, 1996: 145). In a larger study, Bygate (2001) investigated the effect of task type, task type practice and task repetition on task performance. The study involved 48 overseas NNS (nonnative speakers) at the University of Reading. The students were allocated randomly to one of three conditions: narrative group, interview group, and control group. The students were of the same level of proficiency; this was proved by an IELTS (International English Language Testing System) speaking test carried out before the study. Two sets of tasks were designed, a narrative set and an interview set. Each set consisted of six versions of the same type of task (identical). Over ten weeks each experimental group worked on one of the task types. But all three groups did a narrative and an interview task at time 1 and repeated them at time 5. In every two weeks, the experimental groups worked on two versions of the task type. The study showed highly significant results for the independent variables task type and repetition on the fluency and complexity measures but not on accuracy. Bygate (2001) explained the latter by the conservativeness of the measure. The study also showed that task repetition had a strong effect on fluency and complexity. One brief

61

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

encounter with a task 10 weeks earlier seems to have been sufficient to affect subsequent performance of the same task. The results also showed that task-type practice affected only the performance of repeated tasks but not of new versions of the same task-type. Overall, the results suggest that previous experience of a task is available for speakers to build on in subsequent performance (Bygate, 2001: 43). Gass et al. (1999) reported similar results in a study that compared learners use of L2 Spanish in tasks with the same and different contents. They found that task repetition resulted in improvement in overall proficiency. However, they indicated that these findings could not be generalised to a new context. Lynch and Maclean (2000, 2001) investigated the effect of immediate task repetition on performance using a rather different approach. The task was one they had designed in the context of an English for Specific Purposes course designed to prepare members of the medical profession to give presentations in English; a poster carousel task. According to the researchers, their aim in using the task within this study was to gain insight into the content and process of learning, learners perceptions of their learning during the task, and whether there was evidence of short-term gains in language performance. The task involved one hour of planning time, in which a pair of learners had to create a poster based on a research article. Two groups of learners were designated. Each learner took turns (six cycles) to visit the others posters, observe them and then ask questions. Each time a new learner observed and asked questions about a poster, the stationed learner had to respond independently of the previous learner. The study (2000, 2001) showed that task recycling resulted in greater accuracy and fluency. Lynch and Maclean noted that different learners appeared to benefit in different ways, with their level of proficiency as the key factor. In the case of more proficient learners, the main benefit of repetition of the task was in making their explanations

62

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

more lucid and succinct, whereas for lower-proficiency learners, the benefits were greater accuracy and improved pronunciation. Learners varied widely in their awareness of the differences they made in their presentations. Lynch and Maclean (2001) assert that, despite the limitations of the study, it was valuable in highlighting the need for learners to be helped to develop self-monitoring skills, and to analyse others L2 performance, in order to maximise the benefit from the task. Overall, the studies reviewed above suggest that task repetition has very positive effects on learner performance. Bygate (2001) notes the potential benefit to both teachers and students of task repetitions, which could facilitate the focusing of attention on the relationship between form and content. When a task is repeated, the message is already somewhat familiar, so attention can be shifted to the way it is expressed. This section has provided an overview of task-based language learning, teaching and research in the literature. This study aims to contribute to the efforts made in this area by studying the relationship between exposure to different amounts of oral tasks and learners oral production and motivation. The next section reviews some of the literature dealing with the relationship between task and motivation.

3.3

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EXPOSURE TO TASKS AND

MOTIVATION

3.3.1 Introduction In task-based language teaching research, the potential of the task as a motivating activity has been widely recognised (e.g. Brumfit 1984; Harper, 1986; Breen 1987; Candlin and Murphy, 1987; Crookes and Schmidt, 1992; Willis, 1996). Candlin (1987), for example, considers motivation to be a criterion for a good task. In addition, Willis (1996) suggests that the use of tasks is justified when they meet the four conditions of

63

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

language learning, including motivation. However, these scholars did not put much effort into investigating the impact of tasks on learners motivation. Research studies in L2 motivation (e.g., Gardner, 1985; Gardner et al., 1997; Drnyei, 1990; Clement et al., 1994; Noels et al., 2000) emphasise the macro-orientation and learners general action and their relationship with basic motivational influences (e.g. how intrinsic motives or the expectancy of success affect achievement behaviour in general) rather than the specific motives that underlie the completion of particular tasks (e.g. how and why a problem-solving or a narrative task differ in their capacity to engage students) (Drnyei and Kormos, 2000: 277). Only a few efforts have been directed to investigate the relationship between tasks and motivation (Crookes and Schmidt, 1991; Winne and Marx, 1989; Julkunen, 1989; Drnyei and Otto, 1998; Drnyei and Kormos, 2000). Among these efforts Crookes and Schmidt (1991) try to illuminate the effects of the classroom and classroom tasks on motivation, as they link tasks and aspects of classroom activities to some motivational factors identified in the literature (e.g. interest, relevance, and expectancy). Drnyei and Kormos (2000) conducted a novel study in which they explored the effects of a number of affective and social variables such as language use anxiety, effort and need for achievement on foreign language (L2) learners engagement in oral argumentative tasks (p.275). Various aspects of L2 motivation such as attitudes

towards the task and group cohesiveness were used as the independent variables. The dependant variables were the learners language output, in terms of the quantity of speech and number of turns in the oral argumentative tasks. The findings show that situation-specific motives (such as attitudes towards the task, and attitudes towards the course) have a strong impact on the extent of learners task engagement. These results imply that there is a strong relationship between task performance and motivation.

64

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

However, it may be suggested that this relationship is mutual in nature; that is, there is an interrelationship between the task and different motivational aspects. There might be some task characteristics or conditions that affect motivation, which is reflected in the learners engagement in the task. In other words, there is something in the oral task that stimulates or motivates the learners, which in turn affects their engagement in the task, leading to a more active response. What is it in the task that motivates learners? To explore this issue is one aim of the study. It also aims to explore the possible relationship between learners exposure to oral tasks and their motivation in the Saudi context. In addition, it is intended to investigate what effects tasks may have in changing learners motivation over a period of time. However, in order to investigate the relationship between tasks and motivation, it is necessary to establish a theoretical background by reviewing some of the related literature on motivation that may have potential links to tasks and task-based learning. In the literature, there are various approaches (e.g., social-psychological perspective, education-oriented) to describing L2 motivation (Gardner, 1985; Clement, 1980; Keller, 1983; Williams & Burden, 1993, 1997; Drnyei, 1990, 1994, 2001). In what follows, I will first present a survey of Gardners approach to L2 motivation from a socialpsychological perspective, as it is considered the most significant work in SLA studies of motivation. Also, it describes the basic aspects of motivation. I will draw on Skehan (1989) and Crookes and Schmidt (1991) for the discussion of Gardners model. Then, I will present Kellers educationoriented model of motivation and try to relate the four conditions that he identifies to tasks and task-based instruction. After that, educationfriendly approaches to motivation such as Crookes and Schmidt (1991) and Drnyei (1994) will be discussed, as they focus on the classroom and show how motivation is interactive and dynamic. Finally, I present an initial account of the relationship between

65

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

task and motivation as a step towards building a framework. This section draws on the work of Keller (1983), Crookes and Schmidt (1991), Drnyei (1994, 2001), Boekaerts (1988, 1992), Julkunen (1989, 2001) and Ladousse (1982).

3.3.2 Gardners Approach to Motivation The dominant contribution to SLA studies of motivation is that of Gardner and his associates. Initially, Gardners model of motivation was concerned with the learners orientation towards the goal of learning a second language. Gardner and Lambert (1959) made the distinction between integrative motivation and instrumental motivation. Gardner and Lambert (1972) described one kind of motivation as wanting to be esteemed and identified in a foreign setting, to be like the foreign people, and to understand their culture and to participate in it, and labelled this concept integrative motivation, the desire and effort to integrate with a target culture and people (Skehan, 1989). In contrast to integrative motivation, Gardner and Lambert (1972) described instrumental motivation as motivation to acquire some advantages by learning a second language, i.e. learning a second language for practical reasons such as getting a better job or a promotion, or to get better grades in examinations (McDonough, 1986). A learner with instrumental motivation regards learning languages as an instrument to get a reward. Although instrumental motivation also influences second language learning, to the extent that an instrumental motive is tied to a specific goal, its influence would tend to be maintained only until that goal is achieved. Once any chance of acquiring a reward disappears, the learner will stop making any more efforts. On the other hand, if the goal is continuous, it seems possible that an instrumental motivation would also continue to be effective in learning (Gardner and MacIntyre, 1991: 70).

66

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

However, in his later version of his motivational model, Gardner included other components in his motivational construct. Crookes and Schmidt note that Gardner (1985, 1988) points out repeatedly that motivation for language learning includes not only goal orientation, but also (1) the desire to learn the language - whatever the reason, (2) attitudes toward the language-learning situation and the activity of language learning, and (3) effort expended achieving such goals (1991: 475). These elements correspond with the components implied by Gardners later definition of motivation. Gardner (1985: 10) defines motivation as the extent to which an individual works or strives to learn the language because of the desire to do so and the satisfaction experienced in this activity. Gardner argues that these three components belong together because the truly motivated individual displays all three (Drnyei, 1998: 122). In his later definition, Gardner links learners goals and desires to their effort (behaviour) to learn a language, irrespective of the setting (i.e. formal instruction in schools as against informal instruction outside the classroom). However, Gardner considers learning languages to be different from any other school subjects, as Crookes and Schmidt note: Gardners socioeducational model continues to stress the idea that languages are unlike other school subjects in that they involve learning aspects of behaviour typical of another cultural group, so that attitudes toward the target language community will at least partially determine success in language learning (1991: 472). This statement highlights the importance of the social dimension of L2 motivation (Drnyei, 1998). It is reflected in Gardners model of motivation, where the starting point is the social milieu in which the learner is situated. Gardner (1985) proposes that cultural beliefs influence learners disposition towards the specific language group, which in turn is bound to influence how successful they will be in 67

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

incorporating aspects of that language. Two implications can be drawn here. The first implication is that integrative motives and attitudes towards the learning situation are rooted in the social milieu, and influence motivation which, in turn, influences achievement in all acquisition contexts (formal instruction in schools, or informal learning outside the classrooms) (Skehan, 1989: 59). This means that learners come to school with certain dispositions (either positive or negative) and expectations with regard to language learning. The second implication is that there is a causal relationship between integrative motivation and achievement, as Gardner suggests. Gardner (1985) hypothesised that integrative motivation is a cause, and SL achievement is the effect. However, many researchers have proposed the opposite; that is, that achievement might be the cause and motivation the result or effect (Burstall, 1975; Savignon, 1972; Schumann, 1978; Hermann, 1980; Ely, 1986; Crookes and Schmidt, 1991). They proposed that successful second language learners might develop positive attitudes towards the target language and the target language community, whereas unsuccessful learners might have negative attitudes. However, Gardner, relying on a large amount of data, indicates that there is no evidence that achievement influences attitudes and motivation (Skehan, 1989: 64-67). One may suggest that both positions are true, if we consider the construct of motivation to be dynamic and interactive. In this chapter, it is possible to notice the role of achievement in motivation and how motivation is affected by learners achievement, as in the case of Kellers factor of motivation labelled satisfaction of outcome (see Keller (1983), Crookes and Schmidt (1991) on feedback and Drnyei (2001) reviewed in this chapter). The interest in Gardners model for this study comes when we as instructional designers (e.g. Keller, 1983; Ladousse, 1982) look at the influence of the learners motivation on

68

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

his perception of and success in language instruction in the classroom. Instructional design may be evaluated by the extent to which it changes learners motivation, positively or negatively. This is one aim of this study, to study the impact of tasks on learners motivation over a period of time. Finally, the importance of Gardners model is such that it has been described as too influential in the field of L2 motivation (Drnyei, 1994). Crookes and Schmidt, for example, describe it as so dominant that alternative concepts have not been seriously considered (1991: 501). However, Gardners model establishes the basis of L2 motivation research. In addition, as discussed earlier, the main emphasis in Gardners model is on general motivational components based in the social milieu rather than the language classroom. However, these general motivational components (such as attitudes toward learning the language) affect, to some extent, learners success in language learning, as indicated earlier. My interest in Gardners model focuses on this aspect, as I intend to study the influence of different levels of task exposure on learners general predispositions towards language learning. I also intend to investigate the relationship between task and motivation by looking at the impact of task exposure on learners motivation, which has been partly described by Gardner.

3.3.3 Kellers education-oriented model of motivation Unlike Gardner, Keller (1983) investigated the concept of motivation within the language classroom (i.e. the formal instructional context in Gardners model). He concentrates on instruction and instruction design, and motivation as a factor that influences them. Keller (1983) realised the importance of the language learning classroom as a context that is affected partly by certain dispositions brought into the classroom (Gardners motivational aspects) and also by other motivational variables

69

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

(that he identified), which interact with classroom aspects. Keller (1983) proposed four main factors which determine motivation, in his educationoriented theory of motivation: "interest" (labelled attention in his later version, 1994), "relevance", "expectancy", and "outcome" (labelled satisfaction in his later version, 1994). He suggested that the instructional designer must understand and respond to these factors in order to produce instruction that is interesting, meaningful and appropriately challenging. Next, I will try to explain Kellers motivational factors in terms of their definition. No further discussion will be presented here, as these factors will be further illuminated in the discussion of Crookes and Schmidts (1991) motivational model. Kellers first factor, interest, is closely related to curiosity and arousal. Crookes and Schmidt (1991) note that "interest is closely related to curiosity, developing curiosity means using less orthodox teaching techniques and/or materials. Also, change is an essential part of maintaining attention, because otherwise habituation will set in" (pp. 488-89). Drnyei (2001) relates interest to intrinsic motivation, which deals with behaviour performed for its own sake to experience pleasure and satisfaction (2001: 27). The second factor, relevance, is basically determined by "instrumental needs" which "are served when the content of a lesson or course matches what students believe they need to learn" (Crookes and Schmidt, 1991: 482). Keller (1983) observes that human beings have three major needs: the need for achievement, the need for affiliation, and the need for power, i.e., people like to be successful, like to be connected with others, and like to have control over situations or other people. Learners who feel materials or tasks to be relevant to their needs and who have an expectancy of success are highly motivated.

70

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

Relevance thus depends on "what students believe they need to learn," and encompasses three categories or values of learning (Keller, 1983): "personal-motive value", "instrumental value" and cultural value. Personal-motive value suggests that increased value or motivation results when a given task is perceived to offer the satisfaction of a particular need or want. As indicated earlier, the need for achievement is one of the needs identified in the literature (e.g., Maslow, 1987) which caught Kellers interest and can be related to relevance. So, the students feelings of achievement are enhanced when he believes success to be a direct consequence of his effort, when there is a little challenge, and when there is feedback attesting to his success. This view supports what Burstall and others (1974) suggested, that achievement might play a role in affecting learners motivation. Instrumental value refers to the increase in motivation to accomplish an immediate goal when it is perceived to be required for attaining a future and desired goal. Cultural value is the influence of parents, friends, organisations, and the culture on motivation (Keller, 1983: 406-08). Kellers third factor, expectancy, refers to the perceived likelihood of success in participating in any classroom activities. It is related to the learners self-confidence and self-efficacy in general. Self-efficacy refers to the personal conviction that one can execute the behaviour required for successful performance (Keller, 1983: 417). In the language classroom situation, expectancy is related to perceived task difficulty, the amount of effort required, the amount of available assistance and guidance, the teachers presentation of the task, and the familiarity of the task type (this will be discussed further, later) (Drnyei, 2001). Lastly, the outcome or satisfaction of an outcome refers to rewards and punishment in extrinsic motivation, and enjoyment and pride in intrinsic motivation (Keller, 1983).

71

Ch.3: Review of the related literature

Kellers motivational factors are interrelated and sequenced concepts that occur in a specific order when learners encounter classroom activities or tasks. Interest and relevance may occur first when tasks are presented to learners. They perceive tasks in terms of how the tasks affect their curiosity, and how relevant the tasks are to their goals, needs, and wants. Then, expectancy of success (i.e. how successful they will be) in performing the tasks occurs when the learners engage in the tasks. Satisfaction of outcomes comes later, when the learners complete the task and reach an outcome. The results will be evaluated partly in terms of how satisfied the learners are with their results. The significance of Kellers model lies in its focus on the classroom situation. Classroom activities or tasks, for example, can be described in relation to Kellers motivational factors. Kellers model shows the importance of language instruction and classroom activities in relation to motivational factors that describe learners motivation, and are affected by classroom activities, including the task. The significance of Kellers model will be shown next when we discuss Crookes and Schmidts model (1991), as they draw on Kellers model to derive some implications for the classroom and language pedagogy in general.