Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

SPR 05

Hochgeladen von

Muhammad AmerOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

SPR 05

Hochgeladen von

Muhammad AmerCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

1

Figure-Ground Reversal in Linguistic Humour

Tony Veale, School. of Computer Science and Informatics, University College Dublin

1. Introduction

Figure-ground reversal (FGR) is a phenomenon most commonly associated with visual perception, and indeed, few readers will be unfamiliar with the gestalt switches required to process such trick images as the Necker cube (see Fineman, 1996). Nonetheless, FGR is not a phenomenon that is restricted to image processing, and may generally apply to any aspect of cognitive structure where salience can be redistributed from primary to secondary features, that is, from those elements that are highlighted, marked or privileged to those that are not. We thus believe that FGR can play a significant explanatory role in theories of scientific discovery, Gedanken experiments, analogy, metaphor and humour, though prohibitions of space preclude us from considering all but the latter in this abstract. Here we choose to explore the role of FGR in verbal humour, arguing that much of the dynamism, inventiveness and deconstructive playfulness of humour arises from a general cognitive ability to apply FGR at different levels of linguistic and conceptual description.

2. Theories of Humour

The phenomenon of FGR plays a very specific and localized role too localized, we argue in the General Theory of Verbal Humour (GTVH) of Attardo and Raskin (see Attardo and Raskin, 1991; Attardo et al. 2002), a theory which currently dominates the field of humour research. The GTVH essentially offers a script-based incongruityresolution view of verbal humour, in which a narrative may be compatible with multiple scripts, one of which may be more contextually primed than others. Like its progenitor, Raskin's (1985) Semantic Script Theory of Humour (or SSTH) , the GTVH suggests that humour occurs when a listener is deceived into applying a highly primed script that ultimately leads to an incongruity (e.g., see Veale, 2004), an impasse of interpretation that can only be resolved by switching to an apparently less salient script. The GTVH views humorous resolution, whether partial or complete, as the work of a particular logical mechanism (LM) that applies at the level of scripts. Understandably, LMs have proved to be the most enigmatic elements of the GTVH, prompting Attardo et al. (2002) to enumerate a taxonomy of 27 different LMs.

2 For the most part, the GTVH notion of script is grounded in the work of Schank and Abelson (1977), who view scripts as schematic structures that impose a sequential, causal ordering on a narrative and which reflect a single top-down interpretation of events based on an abstracted distillation of relevant episodic memories. GTVH scripts can be activated in one of three ways: lexically (by association with a single word, called the lexical handle of the script); sententially (by a pattern of words and lexical scripts); and inferentially, as a by-product of common-sense reasoning (e.g., as when one intuits that a joke is racist and activates a Racism script). Furthermore, since certain elements in a script will be more salient and foregrounded than others, these elements are marked to distinguish them from less salient background elements. More recently, Attardo et al. (ibid) augment this view with a graph-theoretic account of script representation that views scripts as arbitrarily complex symbolic structures, to which mathematical processes like sub-graph isomorphism can be applied. This representational shift allows the GTVH to encompass even punning as a script-level operation, provided the notion of script is sufficiently generalized to accommodate phonetic as well as semantic information. This generalization, though it increases the descriptive power of scripts, may be purchased at a heavy cost, that of the explanatory power of the GTVH as a theory. We note in passing that a Cognitive-Linguistic alternative to the script-switching account of GTVH is offered by Coulson's (2000) frame-shifting perspective, which situates the process of humour production within the more general framework of Conceptual Integration Networks of Fauconnier and Turner (1998). Coulsons perspective is arguably the more flexible but least developed of the two, since the Cognitive Linguistic notion of frame is more flexible than that of the GTVH notion of script, and so can more easily gain access to the various crevices of language where humour can take root. Since our current focus is the GTVH, we concentrate here on the particular crevices that seem inaccessible to the GTVH but readily accessible to FGR. In the SSTH of Raskin, the incongruities that trigger script switching are purely semantic, based on a fixed catalogue of antonymies like DEATH/LIFE. In contrast, the GTVH offers the possibility that incongruities may arise from a more nuanced spectrum of conceptual and pragmatic concerns. In a further evolution of the SSTH, the GTVH additionally sees humour production as the culmination of a modular process involving a variety of complementary knowledge resources, each determining a different element of a joke, such as narrative structure, logical mechanism, word choice, and so on. As noted earlier, the logical mechanism is the most crucial, and by far the most controversial, modular element of the GTVH. For instance, it is suggested that an LM called falseanalogy is central to jokes whose humour derives from ill-judged comparisons, as in the

3 old joke where a mad scientist builds a rocket to the sun but plans to embark at night to avoid being cremated. Here a false analogy is created between the sun and a light-bulb, suggesting that when the sun is not shining it is not "turned on", and hence, not hot. The GTVH similarly views figure-ground reversal as a specific logical mechanism or LM that constructs a scenario in which two scripts offer inverted interpretations of the same narrative event. For instance, in the joke How many Xs does it take to change a light bulb? 100 one to hold the bulb and ninety-nine to spin the room around, the primed script ("twist the light-bulb") and the unprimed script ("twist the room") make complementary identifications of figure and ground. A switch from the first script to the second thus results in a figure-ground reversal. FGR is here seen by the GTVH as a specific logical mechanism that is literally realized within the world of the joke: the X's in the above actually perform a physical FGR by twisting the room (the ground) rather than the light-bulb (the figure). Attardo et al. (ibid) enumerate six different reversal-based LMs (of 27 in total), such as chiasmus, role exchange and vacuous reversal. However, one cannot help but feel that the designation of FGR as a particular logical mechanism, and reversal in general as a family of LMs, understates the importance of FGR in humour, reducing the phenomenon to a conceit that can be found in any number of related jokes that each instantiate the same template or Ur-joke (see Hofstadter and Gabora, 1989). This is particularly jarring if, as we shall argue, FGR can operate at many different levels of conceptual description, thereby possessing a granularity of application that transcends the level of a simple conceit or formulaic Ur-skeleton.

3. Figure-Ground Reversal as a Pervasive Mechanism of Humour

Indeed, it seems almost paradoxical to assume that a theory of creativity can be constructed on a relatively static substrate of script structures, no matter how baroque the taxonomy of combination mechanisms. Creative humour is surely resistant to analysis by scripts if, by definition, truly novel events cannot be anticipated. Certainly, one needs more flexible notion of script than the top-down formulation offered by Schank and Abelson, since it is highly unlikely that one would already possess a script for turning a room to screw in a bulb, much less a script for stealing wheelbarrows from a factory by filling them with dirt and pushing them though the front-gate. In these jokes, there is not so much a switch between two different scripts but a switch between a standard script and a creative variation of this script. The latter, as a novel construct, cannot be said to exist in advance, and the GTVH offers no mechanism for its construction. Nonetheless, such a mechanism does exist in the guise of figure-ground reversal. Consider the following witticism from the noted gold-digger, and serial divorcee, Zsa Zsa Gabor:

4 Darlink, actually I am an excellent housekeeper. Whenever I leave a man, I keep the house! The GTVH entreats us to view this joke as a juxtaposition of scripts, but where do these scripts originate? Clearly, one can expect to find a housekeeping script in the lexicon, indexed by its lexical handle housekeeper, but where does the juxtaposed meaning a taker and keeper of houses reside? The most obvious answer is that it is constructed dynamically by the hearer, using FGR to deconstruct the conventional meaning housekeeper into a keeper of houses and to reconstruct a new meaning on the fly. Though one can represent this re-conceptualized meaning as a graph structure, it is hardly a script of the GTVH mould. Furthermore, since the comparison of scripts can only follow the dynamic creation of the new script, the re-conceptualized meaning cannot be constructed by an LM, even if that LM is GTVHs concept of figure-ground reversal. Indeed, linguistic humour stretches the notion of script to breaking point with its deconstructive ability to manipulate even the sub-structure of words. Consider humorous word formations like "manunkind", "copyleft" and "McJob", which would require the GTVH to posit some form of "morphology script" before it could gain any sort of explanatory traction. In contrast, FGR easily explains these morphological jokes, since a complex word is a salient figure that is constructed from a backdrop of smaller lexical units. How often do we use complex words like "seminar", "disseminate" and "seminal" without attaching any prominence to the backgrounded words that give rise to them? Whenever a speaker decomposes a complex word into its component units, a figureground reversal must take place, since decomposition gives greater salience to the parts than to the whole. Once alteration of a particular component is performed, as in "right" to "left" to highlight a more liberal attitude to copying, or "kind" to "unkind" to highlight the essential cruelty of humanity, another FGR is required to recombine these parts and return the modified whole to the foreground. In the blending vocabulary of Fauconnier and Turner, (1998), FGR here performs an "unpacking" of a complex word-blend to reconstruct (via the "web-principle") the input spaces that originally gave rise to it. This deconstructive ability of FGR can, more generally, be used to invert the definitional basis of derived concepts, which are those that depend on a logically prior concept (or set of concepts) for their existence. Consider, for the instance, the one-liner If God wanted us to be vegetarians he wouldnt have made animals out of meat. As an animal product, Meat is a derived concept whose existence requires the existence of animals, or, in language of cognitive grammar, Meat is a profiled figure element of the base concept Animal. The effect of FGR on the definition of a derived concept like Meat

5 is to make the profiled figure appear logically independent from its base concept. Freed from this yoke, an agent can explore a notion of meat that is not derived from animals, to perhaps arrive at a new conceptualization of an idea previously taken for granted. Additionally, the joke suggests a new definition of Vegetarian as simply a person whose diet is not derived from animals but who may eat meat from other sources. In effect, the use of FGR introduces some intellectual wiggle-room between two concepts that were previously so tightly-coupled as to be logically inseparable. One might argue that the above joke is humorous only because it employs a line of faulty reasoning (e.g., as might be argued by Minsky (1980), or by Attardo and Raskin via the logical mechanism of false analogy), though we would pointedly disagree with such a diagnosis. Nonetheless, the point is moot because one can invert the definition of a derived concept without doing violence to its underlying logic, as in the satirical remark Eating is over-rated.. Remember, food is just excrement waiting to happen." By playing with tense, the author succeeds in redefining Food in terms of Excrement without affecting the underlying causal order (i.e., that excrement is derived from food). The FGR strategy employed here is the causal equivalent of topicalization, allowing the satirist to move an oblique concept from the causal background into a foreground position. The effect, a form of metonymic tightening (e.g., see Fauconnier and Turner, 1998; Veale and ODonoghue, 2000), strengthens the connection between Food and Excrement to uncomfortably suggest that when one is eating the former, one is simultaneously eating the latter. This tightening is the opposite effect to that created by the Animal/Meat reversal, whose outcome is instead a form of metonymic loosening.

4. Concluding Remarks

The modularity of the GTVH is intended to foster specialized research on different components of humour production independently, much like research in linguistics is advanced by relatively independent inquiries into phonetics, morphology, syntax and semantics. But this extreme modularity is the basis for our gravest concerns about the GTVH. As a research framework, the GTVH seems to liken the operation of humour to that of a kitchen appliance, in which logical mechanisms are little more than the optional whisks and cutting blades that can be attached in different contexts to meet different production needs. It is surely more compelling to believe that figure-ground reversal, rather than serving a detachable role in humour, is instead an intrinsic part of the appliance, perhaps even the motor that drives the rotation of all other components. In this vein, we have argued that FGR is a general tool for performing creative

6 deconstruction, through which humour can take apart and re-assemble objects at almost any level of linguistic description. When applied directly to the level of concepts, it often leads to humour that is both thought-provoking and insightful, changing the way we think about the world and throwing previously tacit connections between concepts into sharp relief. However, this is a level of operation at which the GTVH notion of script, or any comparably static form of representation, seems entirely inappropriate or misplaced.

References

Attardo, S. and Raskin, V. (1991). Script theory revis(it)ed: joke similarity and joke representational model. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 4-3, 293-347. Attardo, S, Hempelmann, C. F. and Di Maio, S. (2002). Script oppositions and logical mechanisms: Modeling incongruities and their resolutions. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 15-1, 3-46. Coulson, S. (2000). Semantic Leaps: Frame-shifting and Conceptual Blending in Meaning Construction. New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Fauconnier, G. and Turner, M. (1998). Conceptual Integration Networks. Cognitive Science, 22(2):133187. Fineman, M. (1996). The Nature of Visual Illusion. New York: Dover, pp. 25,118. Hofstadter, D. and Gabora, L. (1989). Synopsis of the Workshop on Humor and Cognition. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 2(4),417 440 Minsky, M. (1980). Jokes and the Logic of the Cognitive Unconscious. A.I. memo no. 603, M.I.T. A.I. Laboratory. Raskin, V. (1985). Semantic Mechanisms of Humor. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. Ritchie, G. (1999). Developing the Incongruity-Resolution Theory. In the proc .of the 1999 AISB Symposium on Creative Language: Stories and Humour, Edinburgh, Scotland. Schank, R. C. and Abelson, R. P. (1977). Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding. New York: Wiley. Veale, T. and ODonoghue, D. (2000). Computation and Blending. Cognitive Linguistics, 11(3-4), special issue on Conceptual Blending. Veale, T. (2004). Incongruity in Humor: Root-Cause or Epiphenomenon? The International Journal of Humor 17/4, a Festschrift for Victor Raskin.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Malindoma Somé - of Water and The SpiritDokument324 SeitenMalindoma Somé - of Water and The SpiritAkinjolé Ògíyán100% (38)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- George Synkellos The Chronography of George Synkellos PDFDokument725 SeitenGeorge Synkellos The Chronography of George Synkellos PDFPhillip67% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- CovetousnessDokument2 SeitenCovetousnessChris JacksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sing Learn ArabicDokument15 SeitenSing Learn ArabicUmmu Umar BaagilNoch keine Bewertungen

- PressedDokument22 SeitenPressedMohamad AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarah Mohamed Yahia: Social Worker and Kindergarten TeacherDokument1 SeiteSarah Mohamed Yahia: Social Worker and Kindergarten TeacherMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applying Translation Memory Tools in The PDFDokument20 SeitenApplying Translation Memory Tools in The PDFMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of CartoonsDokument13 SeitenHistory of CartoonsMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

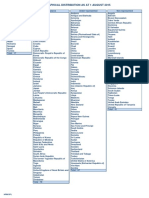

- Geographical DistributionDokument1 SeiteGeographical DistributionMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zoomorphism (Chinese Semiotic Studies) .Pdf20131123 6035 Olrc0a Libre LibreDokument15 SeitenZoomorphism (Chinese Semiotic Studies) .Pdf20131123 6035 Olrc0a Libre LibreMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- English in MindDokument3 SeitenEnglish in MindMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consent To Admission and TreatmentDokument2 SeitenConsent To Admission and TreatmentMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visual Rhetoric: A Situated IntroductionDokument5 SeitenVisual Rhetoric: A Situated IntroductionMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Agreements - SabraDokument627 SeitenCommercial Agreements - SabraMuhammad Amer100% (1)

- Work Statement of Nov. 2012Dokument6 SeitenWork Statement of Nov. 2012Muhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thus, The Research Problem Is Centered On The Following Main QueryDokument5 SeitenThus, The Research Problem Is Centered On The Following Main QueryMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Towards A Definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of The Early Twentieth CenturyDokument30 SeitenTowards A Definition of Islamophobia: Approximations of The Early Twentieth CenturyMuhammad AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lateral Thinking PuzzlesDokument16 SeitenLateral Thinking Puzzlesprabu06051984Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Short Study of The Jataka Atuva Gatapadaya.Dokument2 SeitenA Short Study of The Jataka Atuva Gatapadaya.darshanieratnawalliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poetry Analysis I. MeaningDokument20 SeitenPoetry Analysis I. MeaningDon DeepanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creative Writing Module 4Dokument33 SeitenCreative Writing Module 4Den VerNoch keine Bewertungen

- PENGANTAR TAHAPAN PEMETAAN SISTEMATIS: Bibliometrics Studies, Systematic Mapping Studies, Systematic Literature Review, Dan Scoping Review StudiesDokument7 SeitenPENGANTAR TAHAPAN PEMETAAN SISTEMATIS: Bibliometrics Studies, Systematic Mapping Studies, Systematic Literature Review, Dan Scoping Review StudiesAhmad BaiquniNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitledDokument4 SeitenUntitledGian Reeve DespabiladerasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Midterm Reflective EssayDokument2 SeitenMidterm Reflective EssayAnonymous mMHT6SNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Order of Hermes (1997)Dokument74 SeitenThe Order of Hermes (1997)tyler_durden_480% (5)

- American Literature Between The Wars 1914 - 1945Dokument4 SeitenAmerican Literature Between The Wars 1914 - 1945cultural_mobilityNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECO Heritage 08Dokument160 SeitenECO Heritage 08ParisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anne CarsonDokument3 SeitenAnne CarsonChio Pilar FernándezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jesus at The Center Vocal ChordDokument4 SeitenJesus at The Center Vocal ChordEri CkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beowulf and FosterDokument5 SeitenBeowulf and Fosterapi-241686254Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nirmal VermaDokument8 SeitenNirmal Vermagalena.tsvetkovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Man of La ManchaDokument20 SeitenMan of La ManchakowlarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Higher English Dissertation ThemesDokument8 SeitenAdvanced Higher English Dissertation ThemesCustomPaperWritersUK100% (1)

- Matthew Bible StudyDokument183 SeitenMatthew Bible StudySilvana Ligia100% (1)

- Devdutt Pattanaik-GOD in Indian HistoryDokument3 SeitenDevdutt Pattanaik-GOD in Indian HistoryRejana100% (1)

- Gec 14 UpdatedDokument4 SeitenGec 14 Updatedalyanna dalindinNoch keine Bewertungen

- LiteratureDokument2 SeitenLiteraturewfwefNoch keine Bewertungen

- 'Plutonian Essences' (Or Essences For Plutonian People)Dokument10 Seiten'Plutonian Essences' (Or Essences For Plutonian People)Max Storm100% (4)

- Lacan, J.mirror StageDokument7 SeitenLacan, J.mirror StageGabriel BrahmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Exercise On Tenses Put The Verbs in Brackets Into Their Correct TensesDokument3 SeitenPractice Exercise On Tenses Put The Verbs in Brackets Into Their Correct TensesTrần Minh SơnNoch keine Bewertungen

- U3230366 11388 Grammar-EssayDokument13 SeitenU3230366 11388 Grammar-EssayMỹ Linh TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbos Irregulares en InglesDokument4 SeitenVerbos Irregulares en InglesLorgia Karine Sepulveda PallaresNoch keine Bewertungen