Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

TPK Reddy

Hochgeladen von

Venugopal PNCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

TPK Reddy

Hochgeladen von

Venugopal PNCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Asian Journal of Development Matters Vol 3 (1), January 2009, 79-85 Special Article

Anthropology and Genomics: Reconsideration Parvathi Kumara Reddy Thavanati1* & A Chandrasekar 2

1

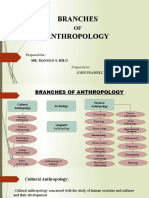

Instituto de Genetica, Departmento de Biologia Molecular y Genomica, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guaadalajara. Jal. Mexico. 2Anthropological Survey of India, Southern Regional Centre, Mysore, India. Introduction Anthropology is a science, which deals with the study of human beings. It tries to understand the socio-cultural and biological aspects of humans in a comprehensive perspective. Strictly speaking in this subject we study about ourselves. Anthropology is neither dead nor dying as pointed out by earlier scholars (Basu and Biswas, 1980; Danda, 1981; Reddy et al., 1993; Rao, 1998), but is progressively growing and developing with its central theme of study of human origin, evolution, migration and spread, and finding the causes of human variations in space and time. The sluggish or worthless anthropologists who entered the discipline accidentally are, unfortunately, trying to triangulate it due to their non-contributive efforts in the discipline.1 Anthropology is often defined as being "holistic" and based on a "four-field" approach. There is an ongoing dispute on this view; supporters (Shore, 1999) consider anthropology holistic in two senses: it is concerned with all human beings across times and places, and with all dimensions of humanity (evolutionary, biophysical, sociopolitical, economic, cultural, psychological, etc.); also many academic programs following this approach take a "four-field" approach to anthropology that encompasses physical anthropology, archeology, linguistics, and cultural anthropology or social anthropology. The

ROAD TRUST 2009

definition of anthropology as holistic and the "four-field" approach are disputed by some leading anthropologists, (Robert, 2002; Robin Fox 1991.) that consider those as artifacts from 19th century social evolutionary thought that inappropriately impose scientific positivism upon cultural anthropology. (Segal, et al 2005) While originating in the US, both the four-field approach and debates concerning it have been exported internationally under American academic influence (Smart 2006). 2 The four fields are: Biological or physical anthropology seeks to understand the physical human being through the study of human evolution and adaptability, population genetics, and primatology. Subfields or related fields include anthropometrics, forensic anthropology, osteology, and nutritional anthropology. Socio-cultural anthropology is the investigation, often through long term, intensive field studies (including participant-observation methods), of the culture and social organization of a particular people: language, economic and political organization, law and conflict resolution, patterns of consumption and exchange, kinship and family structure, gender relations,

Address for correspondence

* Profesory Y Investigador Email: tpkreddy@yahoo.com

Parvathi Kumara Reddy Thavanati & A Chandrasekar

childrearing and socialization, religion, mythology, symbolism, etc. Linguistic anthropology seeks to understand the processes of human communications, verbal and non-verbal, variation in language across time and space, the social uses of language, and the relationship between language and culture. Archaeology studies the contemporary distribution and form of artifacts (materials modified by past human activities), with the intent of understanding distribution and movement of ancient populations, development of human social organization, and relationships among contemporary populations; it also contributes significantly to the work of population geneticists, historical linguists, and many historians. In this paper it is mainly focusing on Molecular Anthropology which emerging and out coming field of Biological Anthropology / Physical Anthropology. What is Molecular Anthropology? Molecular Anthropology is a newly emerging discipline, which synchronizes the theoretical and methodological concepts of physical anthropology and Molecular Genetics in the study of human diseases and promotion of health of human populations. This includes the integral approaches of physical anthropologist with interests in human biology, human genetics, molecular medicine, human growth, development and nutrition, and human being as physical entity, and of a Socio cultural anthropologist whose interests are in the areas of health behavior, medical care (intervention) systems, health planning, psychosomatic illness including mental health, correlation of demographic variables and mainly to trace evolutionary pattern. The

80

contention is that a Molecular Anthropology approach suits the best when it emphasizes the biological basis of health and disease, while at the same time actively incorporating and understanding the socio-cultural and economical constellations involved in the nature of sickness process in the society. In Molecular Anthropology, we use serological and biochemical markers not only in personal identification in forensic science, but also for clinical purposes in prenatal diagnosis of genetic anomalies, genetic counseling, paternity disputes, sports and industry, physiological experiments, etc. Thus, biomedical anthropology has multifaceted applications in diverse fields of science. It is a recent field of academic work called Molecular Anthropology. Molecular because information is derived from large molecules such as proteins and the nucleic acids ribonucleic acids or RNA and deoxyribonucleic acids or DNA. It is Anthropology because we reconstruct the nature of human societies in their pre-literate stages, before industrial life came along. As we are about 150,000 years old and live in industrial society for at most 400 years, molecular anthropology covers most of human history. Traditional Anthropology relied on archaeology (the study of things left behind by humans long after they have perished) as well as paleontology (the study of bones and other anatomical parts) to draw conclusions about human life. Now anthropology draws on additional layer of information provided by molecular biology, which is the study of the structure and function of the large molecules of living organisms. Knowledge of molecules by no means replaces the importance of archaeology or paleontology. It enhances knowledge by introducing another layer, at

Anthropology and Genomics

times confirming what we know from the study of things and bones, and at times questioning it and raising critical debate. Therefore, molecular anthropology stands at the cutting edge of modern biology and the social sciences. UCT human genetics professor Raj Ramesar calls it the crossings' in modern knowledge systems between natural, health and social sciences, as well as the humanities. It is the field that brings to us scientific ancestry testing. A growing business worldwide, everyone is interested in his or her ancestry. Our first curiosity when we meet one another is to decipher where we come from. The study of human genetic polymorphisms is fast and ever-growing branch of Anthropology that holds a great promise for both past and future. Some anthropologists believe that genetic/Molecular Anthropology is a science of future but it must be emphasized that it is a science of the past and present too. DNA is an unbroken link to our ancestors, populations and relatives. Molecular anthropology is useful in estimating the contribution of different gene pools to the make-up of present-day populations and test hypotheses about origin of linguistic and historical population movements. In addition, anthropology is playing a significant role in our understanding of gene-environment interactions and contribution of populations to the detection of genes in common and complex diseases. Anthropologists interested in reconstructing historical population movements and phylogenetic relationships initially used classical genetic data to achieve these aims. Classical genetic data uses proteins and blood groups. The classical genetic data comprehensively provided the basis for the first phase in the development of molecular anthropology, which has been remarkably documented in many international and Indian

81

research compendiums (Bhasin et al., 1994; Bhasin and Walter, 2001; Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994, Mourant et al., 1976, Nei and Roychoudhury, 1988). These large-scale studies have demonstrated that the gene pool is not a simple sum of genes, but is a dynamic system, which is hierarchal organised and which maintains the memory of past events in the history of populations. All genetic information has a historical, anthropological, geographical and statistical context, therefore requires co- operation and collaboration between researchers in different fields. The new or second phase, is utilizing DNA analysis for the reconstruction of human population structure, histories and evolution. The potential benefits from this research are vast and valuable including; a better understanding of the genetic and evolutionary factors that influence populations; an understanding of genetic architecture of common and complex diseases such as diabetes mellitus, dementias, heart and skeletal diseases; and a better understanding of the origin of modern humans. The pattern of genetic variation in modern human populations depends on our demographic history (population migrations, bottlenecks and expansions) as well as gene specific factors such as mutation rates, recombination rates and selection pressure. By examining patterns of genetic polymorphisms we can infer how past demographic events and selection have shaped variation in the genome. Thus, molecular anthropology has important implications for evolutionary biology, disease analyses, and forensics. In this paper, first the anthropological and genomic basis for genetic variation is overviewed followed by some specific empirical research examples highlighting the usage of the molecular anthropological investigations. The focus here is on Indian studies but it cannot be exhaustive due to space considerations (Sarabjit Mastana, 2007).

Parvathi Kumara Reddy Thavanati & A Chandrasekar

Molecular anthropology is able to confirm too that we are the descendents of a single line of human beings and that, at no time have we successfully cross-bred with members of our larger family like the Neanderthals. The idea that we constitute races' is now unquestionably a myth especially as gene flow has reached even the most isolated populations today. History of Molecular Anthropology Structure of human hemoglobin. Hemoglobins from dozens of animals and even plants were sequenced in the 1960s and early 1970s With DNA newly discovered as the genetic material, in the early 1960s protein sequencing was beginning to take off (Wilson and Kaplan 1963). Protein sequencing began on cytochrome C and Hemoglobin. Gerhard Braunitzer sequenced hemoglobin and myoglobin, in total more than 100s of sequences from wide ranging species were done. In 1967 A.C. Wilson began to promote the idea of a "molecular clock". By 1969 molecular clocking was applied to anthropoid evolution and V. Sarich and A.C. Wilson found that albumin and hemoglobin has comparable rates of evolution, indicating chimps and humans split about 4 to 5 million years ago (Wilson, and Sarich (1969). In 1970, Louis Leakey confronted this conclusion with arguing for improper calibration of molecular clocks.(Leakey 1970) By 1975 protein sequencing and comparative serology combined were used to propose that humans closest living relative (as a species) was the chimpanzee.(King and Wilson 1975) In hindsight, the last common ancestor (LCA) from humans and chimps appears to older than the Sarich and Wilson estimate, but not as old as Leakey claimed , either. However, Leakey was correct in the divergence of old and new world monkeys, the value Sarich and wilson used was a significant underestimate. This error in prediction capability highlights a common theme.

82

Advantages of studying molecular Anthropology Two major approaches are used in Molecular anthropology, which involve analyzing DNA. The first and most common approach is to compare the DNA of groups of living organisms, for example, comparing humans to humans or humans to primates. The second approach relies on isolating and analyzing DNA from an ancient source, and comparing it to other ancient DNA or to modern DNA. In both cases, the number of differences between the DNA sequences of the two groups is determined, and these are used to draw conclusions about the relatedness of the two groups, or the time since they diverged from a common ancestor, or both. The essential postulate on which molecular anthropology is based is that closer genetic similarity indicates a more recent common ancestry. All organisms are believed to have evolved from a single ancestor. As different life forms evolved, their DNA began to diverge through the processes of mutation, natural selection, and genetic drift. Even within the same species, populations that do not interbreed will accumulate genetic differences, which increase over time. The number of these differences is proportional to the amount of time since the two groups diverged. There are several advantages to comparing DNA data instead of external physical characteristics (collectively called the phenotype). Environmental factors can shape the phenotype to make two individuals with the same genetic makeup look different. For instance, nutrition has a profound effect on height, and if we used average height to classify humans, we might mistakenly conclude that medieval humans represented different sub-species because they were significantly shorter than modern humans. DNA comparisons, on the other hand, would show no significant difference between these groups. Another advantage is that DNA

Anthropology and Genomics

sequence differences can be easily quantified two base changes in a gene are more different than one. Despite being random events, mutations occur at a fairly steady rate, constituting a "molecular clock," and so the number of differences can be use to estimate the time since the two organisms shared a common ancestor. Finally, since all organisms contain DNA, the sequences of any two organisms can be compared. The same techniques used in molecular anthropology can also be applied to evolutionary questions in other species, to determine the evolutionary relations between different animal species, for instance, or even between bacteria and humans. Critical Progress Critical in the history of molecular anthropology. That molecular phylogenetics could compete with comparative anthropology for determining the proximity of species to humans. Wilson and King realized in 1975, that while there was equity between the levels of molecular evolution branching from chimp to human to putative LCA, that there was an inequity in morphological evolution. Comparative morphology based on fossils could be biased by different rates of change (King M.C.,1975) Realization that in DNA there are multiple independent comparisons. Two techniques, mtDNA and hybridization converge on a single answer, chimps as a species are most closely related to humans. The ability to resolve population sizes based on the 2N rule, proposed by Kimura in the 1950s Kimura M (May 1954). To use that information to compare relative sizes of population and come to a conclusion about abundance that contrasted observations based on the

83

paleontological record. While human fossils in the early and middle stone age are far more abundant than Chimpazee or Gorilla, there are few unambiguous chimpanzee or gorilla fossils from the same period Conclusion Molecular anthropology is a newly emerging discipline, which combines the theoretical and methodological concepts of physical anthropology and Socio cultural anthropology in the study of disease and health of human populations. This includes the integral approaches of physical anthropologist with interests in human biology, human genetics, molecular medicine, human growth and development, nutrition, human being as physical entity and evolutionary biology, and of a Socio cultural anthropologist whose interests are in the areas of health behavior, medical care (intervention) systems, health planning, psychosomatic illness including mental health, correlation of demographic variables and mainly to trace evolutionary pattern.. The contention is that a Molecular anthropological approach functions the best when it emphasizes the biological basis of health and disease, while at the same time actively incorporating and understanding the socio-cultural nature of the sickness process in the society. Molecular anthropologist should move into the design and provision of health services for intervention in improving the health status of certain at risk population groups, extending their life expectancies, lowering morbidity, mortality, arson, sexually transmitted diseases, excessive drinking, and the other like public health issues. The entry of such unique expertise is not only welcome in India, but is imperative also. Thus, the strength of anthropology lies in its analytical potentials, constructive suggestions and practical applications in the society. A Molecular anthropologist has the responsibility to

Parvathi Kumara Reddy Thavanati & A Chandrasekar

Identify him self with the cause and pursue his role and goal with commitment and dedication wherever he is entrusted. I think the study of genetics of various human traits is still a virgin area in anthropology. Deciphering and mapping of genes along with identification of various characters in human genome is a vast unexplored reservoir, with particular reference to Indian lineage. Distribution and spread of various genetic diseases in the world through migrations, admixture and genetic drift, and explaining their concentration in particular geographical and ecological niches is still a challenging task for a Molecular anthropologist in India. Further, using the tools of molecular Anthropology, DNA sequences can be compared among groups to test hypotheses about the evolutionary relatedness of organisms, and about the time that has elapsed since divergence. Molecular anthropology has made major contributions to understanding the migration and mixture patterns of human groups. It has also provided significant new insights into the rise and spread of modern humans and their relation to earlier human groups. As more data becomes available and better models are devised for their interpretation, the results are likely to become less provisional and more certain. Refrences Bhasin, M.K., Walter, H. and Danker-Hopfe, H.: People of India: An Investigation of Biological Variabilityin Ecological, EthnoEconomic and Linguistic Groups. Kamla Raj Enterprises, Delhi (1994). Bhasin, M.K. and Walter, H.: Genetics of Castes and Tribes of India. Kamla Raj Enterprises, Delhi (2001). Basu, A. and Biswas, S.: Is Indian anthropology dead/dying? J. Indian Anthropol. Soc., 5: 1-14 (1980).

84

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P., and Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1994). Danda, A. K.: On the future for anthropology in India. J. Indian Anthropol. Soc., 16: 221230(1981). Han F. Vermeulen, "The German Invention of Vlkerkunde: Ethnological Discourse in Europe and Asia, 1740-1798." In: Sara Eigen and Mark Larrimore, eds. The German Invention of Race. 2006. Kimura M. "Process Leading to QuasiFixation of Genes in Natural Populations Due to Random Fluctuation of Selection Intensities". Genetics 39 (3) (May 1954): 28095. PMID 17247483. PMC: 1209652, http://www.genetics.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view =long&pmid=17247483. King, M.C. & Wilson, A.C.. "Evolution at two levels in humans and chimpanzees". Science 188 (4184): 10716 (April 1975). http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?v iew=long&pmid=1090005 Leakey LS (1970). "The relationship of African apes, man and old world monkeys". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 67 (2): 7468 Mourant, A.E., Kopec, A.C. and Domaniewska-sobczak, K.: The Distribution of the Human Blood Groups and Other Polymorphisms. oxford University Press, London (1976) Rao, V.R.: Physical anthropological research in India and recent advances in recombinant DNA technology: An Approach paper. South Asian Anthropologist, 19: 45- 50 (1998).

Anthropology and Genomics

Reddy, B.M., Vasulu, T.S. and Malhotra, K.C.: Physical anthropology as a science: A commentary. Curr. Sci., 64:17-21 (1993). Ribeiro and Arturo Escobar, eds. World Anthropologies: Disciplinary Transformations in Systems of Power. Pp. 69-85. Oxford: Berg Publishers. Robert Borofsky The Four Subfields: Anthropologists as Mythmakers American Anthropologist June 2002, Vol. 104, No. 2, pp. 463-480 doi:10.1525/aa.2002.104.2.463 Robin Fox (1991) Encounter with Anthropology ISBN 0887388701 pp.14-16 Salzmann, Zdenk. (1993) Language, culture, and society: an introduction to linguistic anthropology. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Sarabjit Mastana,: Molecular Anthropology: Population and Forensic Genetic applications, Anthropologist Special Volume No. 3: 373383 (2007)

85

Segal, Daniel A.; Sylvia J. Yanagisako (eds.), James Clifford, Ian Hodder, Rena Lederman, Michael Silverstein (2005). Unwrapping the Sacred Bundle: Reflections on the Duke Disciplining of Anthropology. University Press. Smart, Josephine (2006) "In Search of Anthropology in China: A Discipline Caught in a Web of Nation Building, Socialist Capitalism, and Globalization." in Gustavo Lins Shore, Bradd (1999) Strange Fate of Holism. Anthropology News 40(9): 4-5. Wilson, A.C. and Kaplan, N.O. (1963) Enzymes and nucleic acids in systematics. Proceedings of the XVI International Congress of Zoology Vol.4, pp.125-127. Wilson, A.C., Sarich, V.M (1969). "A molecular time scale for human evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 63 (4): 108893

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Anthropology Is A Science of HumankindDokument2 SeitenAnthropology Is A Science of HumankindSuman BaralNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACFrOgBv3-RA3cFPlNQB9U WA-MaqYiLiRZChgjf48jlB3JyHnVTlTchyPNwPqQFj8GQWdLyR82sKObD6vaOKB BQ5xptMBNd9IJlfg15IokGHDqbN5UgiE8IHSZEgdZNtC9GKAAKtVs748U W5oDokument8 SeitenACFrOgBv3-RA3cFPlNQB9U WA-MaqYiLiRZChgjf48jlB3JyHnVTlTchyPNwPqQFj8GQWdLyR82sKObD6vaOKB BQ5xptMBNd9IJlfg15IokGHDqbN5UgiE8IHSZEgdZNtC9GKAAKtVs748U W5oAdri ChakraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 Anthr-WPS OfficeDokument6 SeitenChapter 9 Anthr-WPS OfficeAdeljonica MesianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surigao Del Sur State University: Jennifer A. YbañezDokument11 SeitenSurigao Del Sur State University: Jennifer A. YbañezJENNIFER YBAÑEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Winget Poly Technique College 1Dokument178 SeitenGeneral Winget Poly Technique College 1Sintayehu DerejeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diss Lesson 2.1Dokument15 SeitenDiss Lesson 2.1elie lucidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction in AnthropologyDokument44 SeitenIntroduction in AnthropologyAlexandru RadNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnthropologyDokument8 SeitenAnthropologyHabib ur RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolutionary Approaches in CultureDokument3 SeitenEvolutionary Approaches in Culturepauline.tiong15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Dokument38 SeitenIntroduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Anna Liese100% (2)

- Introduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Dokument44 SeitenIntroduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Lysander Garcia100% (1)

- Introduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Dokument31 SeitenIntroduction To Anthropology: Study Guide For Module No. - 1Anna LieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is AnthropologyDokument2 SeitenWhat Is Anthropologyrazel100% (1)

- Soc 102 Course Material 1Dokument10 SeitenSoc 102 Course Material 1bensonvictoria830Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural AnthropologyDokument216 SeitenCultural AnthropologyLev100% (7)

- Diss - Topic 3Dokument41 SeitenDiss - Topic 3Jenelle Arandilla LechadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment of Anthropology: Dembel CollegeDokument16 SeitenAssignment of Anthropology: Dembel CollegeBacha TarekegnNoch keine Bewertungen

- HUSSEIN O. INTRODUCTION TO ANTHROPOLOGY Short Note ForDokument37 SeitenHUSSEIN O. INTRODUCTION TO ANTHROPOLOGY Short Note ForHussein OumerNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Essence of AnthropologyDokument30 SeitenThe Essence of AnthropologyJesseb107Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Term Anthropology Has Been Coined From Two Greek Words Anthropos Which MeansDokument2 SeitenThe Term Anthropology Has Been Coined From Two Greek Words Anthropos Which MeansMerry Jacqueline Gatchalian PateñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundation of Education Ka Rodel Comprehensive ReviewerDokument24 SeitenFoundation of Education Ka Rodel Comprehensive ReviewerLodian PetmaluNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOCANTHRODokument11 SeitenSOCANTHROChristine AloyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Power Point Full (1) .@freshexams PDFDokument107 SeitenAnthropology Power Point Full (1) .@freshexams PDFfiker tesfa100% (2)

- History/background of Sociology and Anthropology: Gengania, Hazel N. Abmcb2bDokument3 SeitenHistory/background of Sociology and Anthropology: Gengania, Hazel N. Abmcb2bCha IsidroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Value of Comparative MethodsDokument7 SeitenValue of Comparative Methodsmhartin orsalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Power Point Full (1) .@freshexams PDFDokument107 SeitenAnthropology Power Point Full (1) .@freshexams PDFtsegabaye7Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is AnthropologyDokument10 SeitenWhat Is AnthropologyAniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Objectives: Applied Biological AnthropologyDokument5 SeitenObjectives: Applied Biological AnthropologyAdnil ArcenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology: Study of Human SocietiesDokument4 SeitenAnthropology: Study of Human SocietiesFELTON KAONGANoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary and Conclusion...Dokument14 SeitenSummary and Conclusion...Manas DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science in AnthDokument5 SeitenScience in AnthJm VictorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenIntroduction To AnthropologyEmilia GaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Chapete 1Dokument6 SeitenAnthropology Chapete 1Abel ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenAnthropologybaekhyunee exoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit I. Introduction To AnthroplogyDokument14 SeitenUnit I. Introduction To AnthroplogycrmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report About Disciplines of Social Sciences.Dokument4 SeitenReport About Disciplines of Social Sciences.Kween Thaynna SaldivarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partido State University: Goa, Camarines SurDokument5 SeitenPartido State University: Goa, Camarines SurRalph NavelinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Course Code: Anth101 Credit Hours: 3Dokument25 SeitenAnthropology Course Code: Anth101 Credit Hours: 3Tsegaye YalewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit One Introducing Anthropology and Its Subject Matter 1.1.1 Definition and Concepts in AnthropologyDokument39 SeitenUnit One Introducing Anthropology and Its Subject Matter 1.1.1 Definition and Concepts in AnthropologyhenosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Unit 1 - 0907211459o7Dokument25 SeitenAnthropology Unit 1 - 0907211459o7brightsunNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Physical Anthropology NotesDokument3 SeitenHistory of Physical Anthropology Notesanon_466257925100% (2)

- Branches Anthropology: Prepared ForDokument24 SeitenBranches Anthropology: Prepared ForCDT Kait Vencent Aballe LequinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Culture and Arts Education in Plural SocietyDokument15 SeitenChapter 1 Culture and Arts Education in Plural Societychristianaivanvaldez.bcaedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Study Anthropology - Anthropology@PrincetonDokument2 SeitenWhy Study Anthropology - Anthropology@PrincetonDarshan KanganeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Power PointDokument135 SeitenAnthropology Power PointTesfalem Legese100% (1)

- Module 3Dokument2 SeitenModule 3jenny ibabaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3Dokument2 SeitenModule 3jenny ibabaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology For PPT FullDokument41 SeitenAnthropology For PPT FullHussein OumerNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Anthropology?: ArchaeologyDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Anthropology?: ArchaeologyMike MarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenIntroduction To AnthropologyTahar MeklaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biocultural Approach The Essence of Anthropological Study in The 21 CenturyDokument12 SeitenBiocultural Approach The Essence of Anthropological Study in The 21 CenturyOntologiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle Wrote "The Human Is by Nature A Social Animal": Main DiscussionDokument5 SeitenAristotle Wrote "The Human Is by Nature A Social Animal": Main DiscussionJohn Kelly PaladNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Handout-1Dokument59 SeitenAnthropology Handout-1Lemma Deme ResearcherNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.3 Main Branches of AnthropologyDokument9 Seiten1.3 Main Branches of AnthropologyRohanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ultural Evolution: A General Appraisal: Jean AyonDokument12 SeitenUltural Evolution: A General Appraisal: Jean AyonToniG.EscandellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropology Power Point Chap1-6-1Dokument106 SeitenAnthropology Power Point Chap1-6-1Mengistu AnimawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolutionary Theory and Technology: The Future of AnthropologyDokument4 SeitenEvolutionary Theory and Technology: The Future of AnthropologyBenny Apriariska SyahraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human EvolDokument12 SeitenHuman EvolAbhinav Ashok ChandelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Branches of SociologyDokument32 SeitenBranches of SociologyDani QureshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACE Alu Insertion Polymorphism In: Croatia and Its IsolatesDokument8 SeitenACE Alu Insertion Polymorphism In: Croatia and Its IsolatesVenugopal PNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidemology of Handigodu DiseaseDokument175 SeitenEpidemology of Handigodu DiseaseVenugopal PN100% (1)

- SC Population in KarnatakaDokument23 SeitenSC Population in KarnatakaArun SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prasna Marga IiDokument242 SeitenPrasna Marga Iiapi-1993729375% (8)

- Wedding Salmo Ii PDFDokument2 SeitenWedding Salmo Ii PDFJoel PotencianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- FACIAL NERVE ParalysisDokument35 SeitenFACIAL NERVE ParalysisIgnasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gelernter, David Hillel - The Tides of Mind - Uncovering The Spectrum of Consciousness-Liveright Publishing Corporation (2016)Dokument263 SeitenGelernter, David Hillel - The Tides of Mind - Uncovering The Spectrum of Consciousness-Liveright Publishing Corporation (2016)রশুদ্দি হাওলাদার100% (2)

- Junto, Brian Cesar S.Dokument1 SeiteJunto, Brian Cesar S.Brian Cesar JuntoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal Teori Pertukaran SosialDokument11 SeitenJurnal Teori Pertukaran SosialRhama PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deluxe SolutionDokument6 SeitenDeluxe SolutionR K Patham100% (1)

- Journal of The Neurological Sciences: SciencedirectDokument12 SeitenJournal of The Neurological Sciences: SciencedirectBotez MartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buad 306 HW 2Dokument4 SeitenBuad 306 HW 2AustinNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 92735 Monarch V CA - DigestDokument2 SeitenG.R. No. 92735 Monarch V CA - DigestOjie Santillan100% (1)

- Thesis Report On: Bombax InsigneDokument163 SeitenThesis Report On: Bombax InsigneShazedul Islam SajidNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS ProjectDokument12 SeitenMIS ProjectDuc Anh67% (3)

- Word FormationDokument3 SeitenWord Formationamalia9bochisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentence Structure TypesDokument44 SeitenSentence Structure TypesGanak SahniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation 1Dokument15 SeitenPresentation 1Ashish SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Grammar Book-Final - 2-5-21Dokument42 SeitenEnglish Grammar Book-Final - 2-5-21Manav GaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Economy: Chapter 6: Comparison and Selection Among AlternativesDokument25 SeitenEngineering Economy: Chapter 6: Comparison and Selection Among AlternativesBibhu R. TuladharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 2 Module 8 1Dokument5 SeitenEd 2 Module 8 1Jimeniah Ignacio RoyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pedagogue in The ArchiveDokument42 SeitenPedagogue in The ArchivePaula LombardiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dallas Baptist University Writing Center: Narrative EssayDokument3 SeitenDallas Baptist University Writing Center: Narrative EssayumagandhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rocketology ProjectDokument6 SeitenRocketology ProjectJosue Grana0% (1)

- Broukal Milada What A World 3 Amazing Stories From Around TH PDFDokument180 SeitenBroukal Milada What A World 3 Amazing Stories From Around TH PDFSorina DanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CrimLaw2 Reviewer (2007 BarOps) PDFDokument158 SeitenCrimLaw2 Reviewer (2007 BarOps) PDFKarla EspinosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Intentionality of Sensation A Grammatical Feature GEM Anscombe PDFDokument21 SeitenThe Intentionality of Sensation A Grammatical Feature GEM Anscombe PDFLorenz49Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rectification of Errors - QuestionsDokument6 SeitenRectification of Errors - QuestionsBhargav RavalNoch keine Bewertungen

- D4213Dokument5 SeitenD4213Ferry Naga FerdianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orgl 4361 Capstone 2 Artifact ResearchDokument12 SeitenOrgl 4361 Capstone 2 Artifact Researchapi-531401638Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Black Box Testing?: Black Box Testing Is Done Without The Knowledge of The Internals of The System Under TestDokument127 SeitenWhat Is Black Box Testing?: Black Box Testing Is Done Without The Knowledge of The Internals of The System Under TestusitggsipuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender Roles As Seen Through Wedding Rituals in A Rural Uyghur Community, in The Southern Oases of The Taklamakan Desert (#463306) - 541276Dokument26 SeitenGender Roles As Seen Through Wedding Rituals in A Rural Uyghur Community, in The Southern Oases of The Taklamakan Desert (#463306) - 541276Akmurat MeredovNoch keine Bewertungen

- All IL Corporate Filings by The Save-A-Life Foundation (SALF) Including 9/17/09 Dissolution (1993-2009)Dokument48 SeitenAll IL Corporate Filings by The Save-A-Life Foundation (SALF) Including 9/17/09 Dissolution (1993-2009)Peter M. HeimlichNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Council of Nicaea and The History of The Invention of ChristianityDokument10 SeitenThe Council of Nicaea and The History of The Invention of Christianitybearhunter001Noch keine Bewertungen