Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Reification of Psychiatric Diagnoses As Defamatory Implications For Ethical Clinical Practice

Hochgeladen von

whackzOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Reification of Psychiatric Diagnoses As Defamatory Implications For Ethical Clinical Practice

Hochgeladen von

whackzCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Ethical Human Psychobgy and Psychiatry, Volume 7, Number I, Spring 2005

Reification of Psychiatric Diagnoses as Defamatory: Implications for Ethical Clinical Practice

Sonja Grover, PhD, CPsych

Lakehead University Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada While the mental health professional generally has beneficent motives and an honest belief in the DSM diagnoses assigned to clients, such diagnoses may yet be defamatory when communicated to third parties. Mental health diagnoses invariably lower the individual's reputation in the eyes of the community. At the same time, DSM diagnoses are but one out of a myriad of possible interpretive frameworks. DSM descriptors for the client's distress thus cannot be said to capture the essence of the client's personhood. When a diagnosis is published as if it captured a definitive truth about an individual psychiatric client, it is, in that important regard, inaccurate. That is, such a communication meets the criterion for a reckless disregard for the truth or an honest belief but without reasonable basis insofar as it is considered to be anything more than a working hypothesis. Hence, in certain cases, DSM labeling may constitute defamation.

Keywords: DSM diagnostic categories, defamation, ethics, clinical practice, mental disorder

hy write an article on whether DSM-IV diagnostic categories (American Psychiatric Association, 1995) might be comprised of terms that are defamatory when communicated beyond the client-therapist context? The answer is that the question of whether the DSM-IV or any subsequent version is potentially defamatory is not a quaint academic intellectual teaser, but rather a fundamental human rights issue. That psychiatric diagnosis is damaging to one's reputation in the community is not generally disputed despite protestations from the progressively minded in some quarters to the contrary: "One could argue that any person who is 'freeze-framed'. .. with an identity as a mental patient finds that identity ultimately damaging" (R.W. Manderscheid, 1993, cited in Susko, 1994, p. 94). Reputation is a vital aspect of personal identity and psychological integrity and one aspect of the human right referred to as "security of the person." When one's reputation is assailed there is generally some level of psychological distress. Birchwood, Mason, and colleagues (1993) found that perceived stigmatization was a significant predictor of depression in persons diagnosed at some point with mental illness. If the assault on one's good name is profound enough there may even ensue a loss of self-esteem and some confusion about self-identity. Further, the loss of reputation can severely impact one's ability to exercise one's liberty rights. This is to say that the diagnosis when published will in all

2005 Springer Publishing Gompany

77

78

Grover

likelihood damage the reputation and interfere with the range and quality of life choices available to the individual so labeled. For instance, should an individual be regarded as untrustworthy and manipulative as a function of their "borderline personality" diagnosis, this may affect employment prospects. If the individual is viewed as volatile and unpredictable given the diagnosis of "anti-social personality disorder," this is likely to affect the potential for successful interpersonal relationships with those who have made such prejudgments based on the diagnosis. The label of "schizophrenic" (even if qualified by the phrase "in remission") may lead to inferences about a potential for future cognitive disintegration and associated lack of mental competence for those who come to know the diagnostic information. This may in turn influence such matters as the individual's bid for political or other responsible office and so on.

CONFIDENTIALITY AND QUALIFIED PRIVILEGE It should be understood that the issue in this paper is not one of breach of confidentiality. Rather, the concern is with the potential defamatory nature of DSM diagnoses even when there is consent for communication of the diagnosis to particular others.^ However, note that the consent may not be truly informed in that the full implications of having the diagnosis and of having it communicated to others may not be adequately understood by the client at the time he or she proffers their consent. Consider in this regard that there is evidence that internalizing the medicalization of one's DSM-defined "mental health problem/disorder" is a strong predictor for depression (White, Bebbington, Pearson, Johnson & Ellis, 2000). Further, it has been found that those who accept explanations of their experience as one of having experienced a "psychotic episode" are also more prone to depression than those who resist integrating the experience in this way (Jackson et al., 1998). One is safe to assume that the client had acceded to the DSM label, to the extent they did, in the hopes that the entire process would alleviate psychological distress. Thus, significant depression as a function of receiving the DSM diagnosis may suggest, at least for some voluntary clients, a lack of full informed consent in subjecting themselves to the diagnostic process and in agreeing to have the diagnosis communicated to certain third parties. (This is aside from the issue of whether the consent to treatment and communication of the diagnosis to others was genuinely voluntary. This is difficult to discern given the societal pressure to cooperate in all respects in the hopes of conforming one's behavior and reports of personal experience to the norm). The client may even have provided consent for the sharing of diagnostic information prior to knowing what diagnosis, if any, would ultimately be communicated. The client may, in some instances, only come to learn the diagnosis at the same time or after the diagnosis is communicated to others, such as a referring physician (as when the client has been referred for psychiatric evaluation as part of the process relating to a personal injury suit which involves a claim for emotional distress). In another example, the client may provide consent for the results of a psychiatric interview to be communicated to an employer as part of the process of substantiating an application for worker's compensation in regard, for instance, to job-related stress. In the latter case, the client may not always fully appreciate the long-term implications (i.e., should the psychiatrist communicate an unexpected diagnosis such as "malingering") (Guriel & Fremouw, 2003). Second, the communication of the diagnosis may be in terms of a definitive statement regarding the essence of the individual, an alleged summary descriptive term, if you will, for the nature of the individual's very personhood. Both of the aforementioned situations meet the

Defamatory Diagnoses

79

criterion for a communication which is not privileged. Although the occasion may be covered by qualified privilege, as when a psychiatrist communicates the diagnosis to the referring family physician, the words written or spoken may yet not be protected. This by virtue of the fact, as mentioned, that there is an absence of truly informed consent authorizing the communication and/or the psychiatric diagnosis constitutes a defamatory statement. It may be defamatory as it reflects a reckless disregard for the truth or a (clinical) belief/presumption without reasonable basis given its reification of both the symptom descriptions and the diagnosis itself without adequate scientific evidence (i.e., there is no consensus on any biological marker and/or the eligibility criteria and/or the disorder as a separable disease or disorder entity). The fallaciousness of reifying DSM diagnostic categories is evidenced, for instance, by the fact that the validity of various long-established DSM categories such as schizophrenia has been attacked in part due to the non-specific nature of many of the attributed symptoms (Gallagher, Gernez, & Baker, 1991). The scientific status of other "conditions" such as "post-traumatic stress disorder" (PTSD) has also been held suspect since there is no certain way to distinguish between the alleged genuine disorder and simple malingering of symptoms. Malingering is a possibility given the subjective nature of the eligibility criteria for disorders such as PTSD, which rely heavily on client selfreports of symptoms. Other diagnoses such as "attention deficit disorder" have been considered by some researchers and clinicians as suspect since there is no biologic marker for the disorder, and no commonly accepted assessment method focusing on symptoms that are not simply continuous with those seen in the non-clinical population (LeFever, Arcona, & Antonuccio, 2003). In addition, the validity of DSM categories in general has been challenged on the basis that often the categories cannot be reliably measured and therefore their validity also cannot be assessed (reliability here referring to mental health workers independently reaching the same conclusions regarding diagnosis when using the same DSM eligibility criteria and the same assessment tools [Kirk, 1994]). Due to such evidence as the foregoing, it is therefore not reasonable to hold DSM categories to be relatively accurate and definitive statements about the nature of the person so diagnosed.

LOSING THE SELF TO THE DSM As a consequence of the DSM diagnosis, is the client, in effect, loses the freedom to redefine him or herself in future. For instance, once a schizophrenic, in practice, always regarded as a schizophrenic (even if "in remission"); once an alcoholic, always considered an alcoholic, but now perhaps a "recovering" alcoholic, and so on. The psychiatric diagnosis thus comes to allegedly reflect something core and always latent in the individual. This notion of continuing risk is sometimes expressed in terms of genetic predisposition to mental disorder even though, as Jacobs (1994) points out, most genetic or biologic disorders do not in fact require a social-environmental contributor in order to become manifest (i.e., the late onset disorders such as Huntington's disease have no identifiable social contributor or trigger). Psychiatric labels impose on the "psychiatrically disordered" individual a self which derives from the story created by the DSM diagnosis. Further, the mental health community is not satisfied until the individual internalizes, to the extent possible, that DSM-defined self (as, for example, schizophrenic). Where the DSM diagnosis is internalized by the client, it is taken to be a sign of at least partial "recovery" and a reason for cautious optimism about the longer-term prognosis. The latter in part since

80

Grover

the client, having acceded to and identified with the assigned DSM diagnosis, will likely also more readily accept the alleged efficacy of particular therapist-preferred treatment modalities, thus ensuring better compliance. The problem is that there is no convincing evidence that DSM categories are anything but one possible interpretive framework among many. Thus the self which is imposed via the DSM story may in fact be fictional and in important ways non-reflective of the lived experience of the subject so named: "The self of narrative identity is the I that tells stories about itself, exists in those stories, and conceives its identity in terms of those stories" (Phillips, 2004, p. 314). Yet, the mentally ill individual often comes to embrace the DSM diagnosis, given the pressure to do so and since the DSM diagnosis provides a unifying framework for interpreting the varied and often confusing experiences which the individual considered "mentally ill" may be undergoing. The fact that providing such a unifying story may be emotionally and intellectually satisfying to those who are doing the labeling of such disturbing phenomena as psychosis (and perhaps also to the client) does not, however, in itself establish that the diagnosis is veridical. Indeed, it may be that the disordered individual is, through their symptomatology, telling their own story. In doing so they may be engaged in constructing a new identity (self), one that others (or even they) may not always apprehend but a story that captures their lived experience more adequately than does the DSM diagnosis. In practice, society regards: "narrative identity . . . as a mark of what it is to be a person or a self (Phillips, p. 326). Hence, the DSM narrative too defines the individual's personhood. The question then becomes just how accurate and useful that DSM story is. DSM categorization has important psychological effects in that "the way in which individuals label their experiences has been associated with perceived quality of life" (Lobban, Barrowclough, & Jones, 2003, p. 178). To the extent that the DSM label robs the individual of his or her self-constructed self and de-contextualizes the experience, psychological damage may ensue. This damage is then additional to any previous distress caused by the symptoms associated with the mental disorder. Thus, for instance, individuals have been found to be more likely to suffer post-psychotic depression when they attribute their psychotic symptoms to something "internal to the self as opposed to contextual factors (Birchwood, Iqbal, Chadwick, & Trower, 2000a, 2000b). This focus on an internal locus for the cause is more likely when a DSM conceptual framework is relied upon to make sense of symptoms given the underlying medical model. Biologic explanations of psychiatric symptoms may relieve stress in the short-term for some by relieving personal responsibility for the "illness." However, such explanations may cause considerable distress in the longer term due to their engendering a sense of lack of internal control and a separate but unwelcome identity as someone constitutionally different from the nonclinical population (McGorry & McConville, 1999). The individual loses not only the freedom to redefine their essence apart from the diagnosis but also the freedom to assign their own meanings to their personal distress and experiences. Rather, these experiences are translated into symptoms devoid of personal meaning and these symptoms into diagnostic categories emanating at the root from some biologic cause over which the client has no control. The choice is to internalize the language of the therapist in assigning any meaning to the experience of "mental illness" or to resist and be left with no one with whom to share any sort of social reality at all: Modern . . . medicine does not typically pay attention to patient's interpretations of their symptoms and illnesses. . . . With naming comes a transfer of ownership of the person's mind and body to the professional. If someone's brain is diseased, that individual ceases

Defamatory Diagnoses

81

to be viewed as a responsible owner of his or her mind/body. (Susko, 1994, p. 93, some emphasis added) In essence, DSM tells its own stories. From the DSM perspective, the client's stories and meanings are but a reflection of illness rather than meaningful to any degree and generally not viewed as a potential vehicle for moving toward self-efficacy.

DSM AS AN INTERPRETIVE VERSUS OBJECTIVE, EMPIRICAL DIAGNOSTIC SYSTEM The DSM-IV diagnostic categories and any future revisions are better viewed as interpretive frameworks rather than objective descriptive or scientifically confirmed explanatory conceptual systems. As one author has put it: "The caseness approach [referring to DSM categorization] engenders a certain story and meaning, but it is essentially the same story for everyone who is so labeled: 'I have a mental illness caused by a chemical imbalance in my brain . . .'" (Susko, 1994, p. 96, portion in square brackets added for clarity). The point here is not to diminish the possibility of important biological contributors to various behaviors and processes that we might label mental illness or to deny the suffering that is often associated with such states. Rather, what is being highlighted is the tenuous nature of a DSM diagnosis when it is held to capture who this person is or has become. In this regard, consider that even if one were to understand fully the biological contributors to a manifestation of mental illness, one would not necessarily comprehend the personal meaning of the particular form and content of symptoms, nor how they relate to and reflect the individual's history and current concerns (compare Georgaca, 2004) The DSM-IV as currently employed creates the implicit pretense, however, that one can categorize not just "symptoms" but the people who express them. The DSM categories serve to equate the person with the symptoms. For instance, one does not simply have schizophrenia; one is a schizophrenic; one does not just have obsessive-compulsive disorder; one is an obsessive-compulsive. This trend is more pronounced for the "mental illnesses" than for most any other disorders recognized as importantly biologically based even when there are psychiatric correlates or effects associated with the disorder. The DSM categories define who one is and not just what one has in the way of symptom expression or disease entity be the latter regarded as a mental or physical phenomena or both. Yet, it has been shown that even persons with significant psychotic symptomsto use the DSM conceptual frameworkcan often be trained how to modify or reduce their psychiatric symptoms by altering their beliefs about them (Tarrier, Harwood, Yusopoff, Beckett, &. Baker, 1990). Since the expression of many of the mental "disease" categories listed in the DSM can, at times, be altered as a function of the client and the therapist's beliefs about the "condition," there is not necessarily any static truth embedded in the DSM categories. Thus, in communicating a DSM diagnosis, the psychiatrist or other mental health worker errs if the presumption is that the diagnosis captures something fundamental about the core of the client's personhood. In respect of certain DSM categories, such as sociopathy, it is even widely but incorrectly assumed among many in the field that something about moral character and not just personality or cognitive style is being conveyed. The contention here is, in contrast, that there exists no professional or scientific expertise sufficient to define, categorize, or describe the complexities of another's personhood.

82

Grover

Even when the client is psychotic, the DSM does not capture the unchanging essence of that human being. There is in such a case a personhood present as opposed to a vacuum into which the psychiatrist can properly inject his or her own version of the individual's being by attributing to the client the persona defined by a particular DSM diagnosis. Thus it is that cognitive behavior therapy has some efficacy in that psychotics can be assisted in altering belief systems that underlie delusions and such so as to develop a new world view and construct their old or a new persona (i.e., Ghadwick & Birchwood, 1994; Freeman et al., 1998; Lewis et al., 2000; Wykes, Parr, & Landau, 1999). These cognitive behavior therapy approaches have been referred to as "normalizing." This in that they are premised on a notion of a dimensional definition of mental illness where symptoms and complexes of symptoms are viewed as on a continuum existing in both the clinical and non-clinical population, rather than as indices of who has or does not have a disorder (Johns &J. Van Os, 2001, p. 1137). (Distinguishing features between the two groups may thus be in terms of frequency and severity of symptoms or instead ability to cope with the symptoms, or combinations of such factors or the like.) Note also that recovery seems to be facilitated when persons who have experienced what is generally referred to as a psychotic episode "split ofP' the experience rather than integrate it into the self (McGlashan, Levy & Carpenter, 1975). In the latter case, it is as if the individual has come to cope by adopting the view that psychiatric symptoms can occur also in the general non-clinical population but do not define the self. There is also evidence of the potential ability to control to a degree those psychiatric symptoms, even psychotic symptoms, by altering beliefs about the symptoms, their cause, meaning, and controllability. These findings challenge the utility of a view of the severely mentally disordered as manifesting some sort of disease entity that can be treated but symptomatically leaving essentially unaltered the underlying constitutional difference which predisposes the individual to mental illness given the right circumstances.

ON THE VERACITY OF DSM CATEGORIES The veridical quality of the DSM as a means of differentiating "us" from "them" has been undermined given the presence of psychotic traits and symptoms in non-clinical populations. Not only is there a notable prevalence rate of psychotic symptoms such as auditory hallucinations occurring in the non-clinical population at some point in their lives even when not under stress^ (the rate varying depending on the measure used), but there is also an association between various reported psychotic symptoms within individuals in non-clinical groups (Johns & J. Van Os, 2001). Thus mental health symptoms are viewed by some experts in the field as on a continuum with normal experience rather than as indices of a disease entity with symptom clusters that can be categorically defined as in the DSM:

. . . dimensional definitions of symptoms can be less stigmatizing than categorical distinctions, as they imply that patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia [for example] are not distinctly different from non-patients. In contrast, the categorical view of schizophrenia as a qualitatively different disease experience facilitates the frequently observed process of equating the person with his or her illness. (Johns &J. Van Os, 2001, p. 1137)

Thus there is disagreement in the medical and psychological literature about whether "mental illness" (a) represents: a state quite different from that experienced by segments of the non-clinical population or (b) reflects symptoms occurring in the non-clinical

Defamatory Diagnoses

83

population as well but exacerbated due to inadequate coping that may be compounded also by inadequate social support (Jacobs, 1994). DSM diagnosis communicated to a third party is then not covered by the justification defense (truth defense) to the degree that it conveys a notion of some understood highly distinctive disease process of mind and/or body that sets the individual apart in some very fundamental way from the nonclinical population. In fact there is controversy about whether severe mental disorder is biologically based, a function of a combination of biologic and social factors, or (iii) solely the consequence of "imposed suffering" to which such individuals have been exposed for "substantive periods of their formative years" (Jacobs, 1994, p. 17) (the latter perhaps creating psychopharmacological effects within the body such that cause and effect are no longer distinguishable). Regardless of one's theoretical orientation, what is clear is that many mental health experts espouse substantively different conceptions of mental illness. The reality of various DSM categories and the system as a whole is thus highly contentious, as reflected in the following quotes: . . . the recognition of disorder is a social and interactional issue both in the sense that the judgment of disorder is based on social criteria and in the sense that diagnosis is an interpersonal process with its own inherent social order. (Georgaca, 2004, p. 87, commenting on the work of Palmer, 2000) Others argue that diagnosis is not a process of identification or recognition of disorder, but rather a process of active construction of disorder and of transforming the person to a mental patient. (Georgaca, 2004, p. 87) We have argued . . . that research on psychotic speech maintains the concept of thought disorder by ignoring the role of the listener, rater and researcher in the assessment of the intelligibility of speech. (Georgaca, 2004, p. 88) The DSM diagnosis therefore, depending on one's perspective as a mental health theoretician/practitioner, may be grounded to differing degrees, if at all, on the existence of therapist-interpreted actual symptom clusters relating to particular disordered mental processes and/or diseases. "Mental illness" is thus variously considered biologically based with markers yet to be discovered or as a social construction influenced by the sociocultural context in which the symptoms and the diagnostic classificatory scheme emerged (or something in between) (Georgaca, 2004). For a concrete example of mental illness as a social construction, consider the ongoing debate on whether Asperger's syndrome (a diagnostic category included in the DSM-IV) represents a separate diagnostic category or subcategory or in fact does not exist at all (these individuals being rather high-functioning autistics that cannot be differentiated in terms of substantively different eligibility criteria than those used to screen for autism) (Dickerson Mayes, Galhoun, & Grites, 2001). Gommunication of the diagnosis to persons other than the clienteven when covered by qualified privilegecannot then be defended via "justification" (the truth defense). This is due to the wide range of perspectives among mental health professionals on the uniqueness and even very existence of the condition or symptoms referred to by the diagnosis. Who and how one is labeled may have less to do with an accurate scientifically-based description of any unique mental characteristics of the individual than with: (a) who is at highest risk of such labeling having become caught up in the mental health system and (b) who is at highest risk of having their "symptoms" viewed as maladaptive. This once more is not to deny that mental illness may involve suffering but how much of that suffering is maladaptive and/or due to the experience itself and how much is due to society's reaction to it is unclear.

84

Grover

The interpretive nature of the DSM categorization scheme is constantly underplayed or, on occasion, even ignored in much of the mainstream literature. Instead, there is "an empiricist account when describing diagnosis as a process of objectively identifying symptoms independently of the clinician's characteristics and orientation" (Georgaca, 2004, p. 88). In the present context, this is an essential point in that it explains why the notion of a psychiatric diagnosis assigned by a mental health worker is generally not held to be defamatory. Such diagnoses are inappropriately regarded as objective and non-interpretive. As these diagnoses are made in good faith, the contention has been in almost every instance that they are ipso facto non-defamatory even when communicated to third parties and even if unanticipated damage to the client's reputation results. The argument here has been, however, that to the extent that the diagnosis refers to some presumed fundamental truth about the client's "self or "person" (something more than but a theoretical description of interpreted behaviors) then the words spoken or written are defamatory and unprotected. That is, the communication demonstrates a reckless disregard for the truth or a belief without reasonable basis that cannot be saved by qualified privilege and which causes in many instances deep personal injury. That personal injury arises since the diagnosis may be perceived by self and others as a kind of social declaration that the individual has lost the self to some degree or perhaps even completely. Such a perceived "loss of autonomy" and "entrapment in the illness" has been associated with a greater likelihood of feelings of humiliation and depression for individuals diagnosed with psychiatric illness (Birchwood, Iqbal, et al, 2000a, 2000b; Birchwood, Mason, et al., 1993).

CONCLUSION We have considered the possibility that DSM diagnosis may simply be a tool in a tautological process in which the "diagnosis.. . frames which symptoms are noted and reinforced" (Susko, 1994, p.92) and serves to reify the diagnostic category. As a result, the psychiatrist or other mental health worker is often misled into a feeling of confidence regarding the diagnosis given that it is they themselves who have imbued it with such meaning. That meaning derives from the fact that the therapist "discovers" in the client's complex of therapist-interpreted behaviors a set of "symptoms" that are weighted so as to confirm the diagnosis (compare Barrett, 1998). This is much as it is for the reader of personal astrological chart predictions. The reader finds meaning in their astrological personality profile as a consequence of they themselves creating the artificial links between the complex happenings of their personal lives on the one hand and the rather non-specific descriptions and predictions in the astrological reading. To avoid this pitfall, mental health workers must come to regard DSM categories and eligibility criteria as but "working hypotheses" (whether viewed in terms of categories or the dimensional perspective emphasizing symptoms as occurring along a continuum such that there is no dichotomy between clinical and non-clinical groups in terms of the presence or absence of such symptoms in either group). These psychiatric diagnoses are to be assessed then in terms of what good they do for the client in terms of increasing their self-efficacy and joie de vie and revised when they do more harm than good. With that cautious approach DSM categories or a dimensional analysis may be a possible tool for considering certain theoretical perspectives in working with a client rather than defamatory labels that assign an individual a static and damaging persona. Too often mental health clients have been denied the right to be protected from exacerbations of their mental anguish through psychiatric diagnoses which: (a) reduce their

Defamatory Diagnoses

85

complex and dynamic selves to a static reified DSM category and (b) lead to inferences about some profound deficit in the cognitive, affective, and/or moral domain, the origin of which is held to be for the most part internal rather that a function of the dynamic sociocultural context or interplay between the biological and contextual factors. The end result then is a defamatory labeling which negates the individual's autonomous self apart from that self as conceptualized through the lens of the DSM. Justice demands that communication of DSM categorical diagnoses as reified mental disease entities that accurately describe or explain the self of the individual so labeled should result in legal liability for the mental health professional publishing the diagnosis. Afterall, justice is a basic human need, as Taylor explains (2003), which every person is entitled to have met. The psychiatric patient must then not be precluded from using the defamation law to restore his or her dignity, sense of self, and good standing in the community when the circumstances warrant. Hopefully, the language used in conveying interpretations using the DSM will be tentative, as it should be if clinical practice is to meet a higher ethical standard in this regard.

NOTES 1. TTiere are a myriad of ways in which DSM diagnoses are communicated to parties other than the client with or without the client's informed consent. For example, sucb diagnoses may become public when tbe individual is involuntarily committed and the information is communicated to family members who are caretakers or to other physicians as a result of a routine consultative process. Where the client is hospitalized or under court order it may be communicated to the various attorneys and other court officials without the client's consent. Schoolchildren may have sucb diagnoses in their school records to whicb open access is granted to various school personnel witb the records following the child after a school transfer, thus spreading the DSM label to an ever-wider circle. Tbus tbe childtbe actual clienthas not provided consent. It can be argued tbat the legal guardian cannot be presumed in every sucb case to bave provided genuine proxy consent "on bebalf' of tbe child. This is the case since tbe child might not have provided sucb consent bad tbey been competent and understood tbe potential negative implications of baving tbe diagnosis made public. 2. For example, the non-clinical individual may be a new anxious mother wbo clearly hears her baby cry for her mother though the infant has in fact not made a sound, or an adult mourning the loss of a loved one wbo hears tbe deceased's voice while being aroused from a nap.

REFERENCES American Psycbiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic ar\d statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Barrett, R. J. (1998). Clinical writings and tbe documentary construction of schizophrenia. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 12, 265-299.

Birchwood, M., Iqbal, Z., Cbadwick, P., & Trower, P. (2000a). Cognitive approach to depression and suicidal thinking in psycbosis: I. Ontogeny of post-psycbotic depression. British Jouma! of Psychiatry, J77, 516-521. Birchwood, M., Iqbal, Z., Cbadwick, P., & Trower, P (2000b). Cognitive approacb to depression and suicidal thinking in psycbosis: II. Testing the validity of a social ranking model. British

Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 522-528.

Birchwood, M., Mason, R., MacMillan, F, et al. (1993). Depression, demoralization, and control over psychotic illness: A comparison of depressed and non-depressed patients with chronic psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 23, 387-395.

86

Grover

Chadwick, P., &. Birchwood, M. (1994). The omnipotence of voice: A cognitive approach to auditory hallucinations. British Jouma! of Ps;yc/iiacr)i, 164, 190-201. Dickerson Mayes, S., Calhoun, S. L., & Crites, D. L., (2001). Does DSM-IV Asperger's disorder existl]oumcd of Abnomml Child Psychology. 29, 263-271. Freeman, D., Garety, P., Fowler, D., Kuipers, E., Dunn, G., Bebbington, P., et al. (1998). The London-East Anglia randomized control trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for psychosis IV: Selfesteem and persecutory delusions. British ]oumal of Clinical Psychohgy. 37. 415-430. Gallagher, A. G., Gemez, T., & Baker, L. J. V. (1991). Beliefs of psychologists about schizophrenia and their role in its treatment. lrish]oumal of Psychobgy. 12. 393-405. Georgaca, E. (2004). Talk and the nature of delusions: Defending sociocultural perspectives on mental illness. Phibsophy, Psychiatry, arui Psychobgy. 11, 87-94. Guriel, ]., & Fremouw, W. (2003). Assessing malingered post-traumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Clinical Psychobgy Review. 23. 881-904. Jackson, H. J., McGorry, P. D., Edwards, J., Hulbert, C , Henry, L. Francey, S., et al. (1998). Cognitively-oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE): Preliminary results. British Journal of Psychiatry. 172(Suppl. 33), 92-99. Jacobs, D. H. (1994). Environmental-failure-oppression is the only cause of psychopathology. The ]oumd of Mirul and Behavior. 15. 1-19. Johns, L. C , & J. Van O's (2001). The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clinical Psychobgy Review. 21. 1125-1141. Kirk, S. A. (1994). The myth of the reliability of DSM. The Journal of Mind and Behavior. 15. 7186. LeFever, G. B., Arcona, A. P., & Antonuccio, D. O. (2003). ADHD among American schoolchildren. The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice. 2(1). Retrieved April 13, 2004, from http://www.srmhp.org Lewis, S. W., Tarrier, N., Haddock, G., Bentall, R., Kinderman, P., &. Kingdon, D. (2000). A multicentered randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy in first- and secondepisode schizophrenia: The Socrates trial. Schizophrenia Research. 36 (1-3), 329. Lobban, E, Barrowclough, C , & Jones, S. (2003). A review of the role of illness models in severe mental illness. Clinical Psychobgy Review, 23. 171-196. McGorry, P. D., & McConville, S. B. (1999). Insight in psychosis: An elusive target. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40, 131-142. McGlashan, T. H., Levy, S. T. & Carpenter, W. T. (1975). Integration and sealing over: Clinically distinct recovery styles from schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32. 1269-1272. Palmer, D. (2000). Identifying delusional discourse: Issues of rationality, reality and power. Sociobgy of Health and Illness. 22, 661-678. Phillips, J. (2004). Psychopathology and the narrative self. Phibsophy, Psychiatry, and Psychobgy. 10. 313-328. Susko, M. A. (1994). Caseness and narrative: Contrasting approaches to people who are psychiatrically labeled. The Journal of Mirui and Behavior. 15. 87-112. Tarrier, N., Harwood, S., Yusopoff, L., Beckett, R., & Baker, A. (1990). Coping Strategy Enhancement (CSE): A method of treating residual schizophrenic symptoms. Behavioral Psychotherapy. 18, 283-293. Taylor, A. J. W. (2003). Justice as a basic human need. New Ideas in Psychobgy, 21. 209-219. White, R., Bebbington, P., Pearson, J., Johnson, S., & Ellis, D. (2000). The social context of insight in schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 35, 500-507. Wykes, T, Parr, A. M., & Landau, S. (1999). Group treatment of auditory hallucinations: Exploratory study of effectiveness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 180-185. Offprints. Requests for offprints should be directed to Sonja Grover, PhD, CPsych, Lakehead University, 955 Oliver Road, Thunder Bay, Ontario, P7B 5E1, Canada. E-mail: sonja.grover lakeheadu.ca

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- NARCISSISTIC ABUSE RECOVERY: Healing and Reclaiming Your True Self After Narcissistic Abuse (2023 Guide for Beginners)Von EverandNARCISSISTIC ABUSE RECOVERY: Healing and Reclaiming Your True Self After Narcissistic Abuse (2023 Guide for Beginners)Noch keine Bewertungen

- In Roads: A Working Solution to America's War on DrugsVon EverandIn Roads: A Working Solution to America's War on DrugsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Competence in the Law: From Legal Theory to Clinical ApplicationVon EverandCompetence in the Law: From Legal Theory to Clinical ApplicationNoch keine Bewertungen

- SACRED INTIMACY: Navigating the Spiritual Dimensions of Love, Connection, and Sacred Intimacy (2024 Guide for Beginners)Von EverandSACRED INTIMACY: Navigating the Spiritual Dimensions of Love, Connection, and Sacred Intimacy (2024 Guide for Beginners)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: "American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment" by Shane Bauer - Discussion PromptsVon EverandSummary: "American Prison: A Reporter's Undercover Journey into the Business of Punishment" by Shane Bauer - Discussion PromptsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Forensic Psychology: Court, Law Enforcement, and Correctional PracticesVon EverandIntroduction to Forensic Psychology: Court, Law Enforcement, and Correctional PracticesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Offences Act 2003 NotesDokument9 SeitenSexual Offences Act 2003 NotesMahdi Bin MamunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeVon EverandManual on the Character and Fitness Process for Application to the Michigan State Bar: Law and PracticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nolle Prosequi: This is what being brave and disclosing sexual assault really looks like; police seldom prosecute and there is no justice.Von EverandNolle Prosequi: This is what being brave and disclosing sexual assault really looks like; police seldom prosecute and there is no justice.Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Product of Insanity: Understanding Uniform Powers, Uniformity, Futuristic Military Dominancy 21St Century Thesis Ideological Warfare and More......Von EverandA Product of Insanity: Understanding Uniform Powers, Uniformity, Futuristic Military Dominancy 21St Century Thesis Ideological Warfare and More......Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reclaiming Your Power: Overcoming Malignant Narcissism in RelationshipsVon EverandReclaiming Your Power: Overcoming Malignant Narcissism in RelationshipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Business of Policing: Volume I: Crimes & PunishmentsVon EverandThe Business of Policing: Volume I: Crimes & PunishmentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of Expert Testimony On Intimate Partner ViolenceDokument12 SeitenUse of Expert Testimony On Intimate Partner Violencemary engNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of RapeDokument6 SeitenTheories of RapeSaloni GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rizona Ourt of PpealsDokument8 SeitenRizona Ourt of PpealsScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychiatric Aspects ... Sex Offenders - GORDON, 2004Dokument8 SeitenPsychiatric Aspects ... Sex Offenders - GORDON, 2004Armani Gontijo Plácido Di AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 407 Undue Influence A Framework For Recognizing Investigating RespondingDokument59 Seiten407 Undue Influence A Framework For Recognizing Investigating RespondingMohamed NumanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jwnotice of Privacy Practices - Mental Health As of 09 13Dokument8 SeitenJwnotice of Privacy Practices - Mental Health As of 09 13api-281744106Noch keine Bewertungen

- Virtual Voodoo - The Lie Detector LieDokument16 SeitenVirtual Voodoo - The Lie Detector LieRobert F. Smith100% (2)

- Insert Surname 1: Family Court System Fails To Adopt The Fundamental Elements of A Fair TrialDokument13 SeitenInsert Surname 1: Family Court System Fails To Adopt The Fundamental Elements of A Fair TrialBest EssaysNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Common Medical Malpractice Defense ArgumentsDokument5 Seiten10 Common Medical Malpractice Defense ArgumentsDanson NdundaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intentional Infliction of Emotional DistressDokument2 SeitenIntentional Infliction of Emotional DistressLitvin EstheticsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michigan Application For Leave To Appeal From Court of Appeals On Denying Relative AdoptionDokument146 SeitenMichigan Application For Leave To Appeal From Court of Appeals On Denying Relative AdoptionBeverly Tran100% (1)

- The Role of Mental Imagery in The Creation of False Childhood MemoriesDokument17 SeitenThe Role of Mental Imagery in The Creation of False Childhood MemoriesCristina VerguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domestic ViolenceDokument15 SeitenDomestic Violenceapi-356574540Noch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Ethics in Child Custody and Dependency ProceedingsDokument7 SeitenLegal Ethics in Child Custody and Dependency ProceedingsmikmaxinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint - Fed. Court - Amended - SAVE MANUALLY - Accept Not AccepartDokument99 SeitenComplaint - Fed. Court - Amended - SAVE MANUALLY - Accept Not AccepartValS100% (1)

- False Allegations of Child Sexual Abuse by Children Are RareDokument2 SeitenFalse Allegations of Child Sexual Abuse by Children Are Raresmartnews100% (1)

- MTN For Reconsideration of Detention OrderDokument50 SeitenMTN For Reconsideration of Detention OrderTom KirkendallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Issues in Domestic Violence Civil CasesDokument22 SeitenEvidence Issues in Domestic Violence Civil CasesBernice Purugganan Ares100% (1)

- Fathers Count Bill To Fund Men's Custody MovementDokument3 SeitenFathers Count Bill To Fund Men's Custody MovementAnotherAnonymomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Supervised Release Must EndDokument3 SeitenWhy Supervised Release Must EndJabari ZakiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dark Triad Examining Judgement Accuracy The Role of Vulnerability and LinguisticDokument382 SeitenThe Dark Triad Examining Judgement Accuracy The Role of Vulnerability and LinguisticMari Carmen Pérez BlesaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explaining Counterintuitive Victim BehaviorDokument4 SeitenExplaining Counterintuitive Victim BehaviorSharona FabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crilaw ExtortionDokument1 SeiteCrilaw ExtortionAlana ChiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custody Disputes Involving Domestic ViolenceDokument55 SeitenCustody Disputes Involving Domestic ViolenceDr Stephen E DoyneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1998 - Coercion and Punishment in Long-Term Perspectives - McCordDokument405 Seiten1998 - Coercion and Punishment in Long-Term Perspectives - McCordnermal93Noch keine Bewertungen

- AlphabeticalDokument3 SeitenAlphabeticalBrian VispoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mandatory Reporting Requirements: Children: Questions Arkansas Louisiana TexasDokument14 SeitenMandatory Reporting Requirements: Children: Questions Arkansas Louisiana TexasCurtis HeyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Battered Woman SyndromeDokument9 SeitenBattered Woman SyndromeMarie Rose Bautista DeocampoNoch keine Bewertungen

- DePuy Appeals Verdict in California CasesDokument98 SeitenDePuy Appeals Verdict in California CasesLisa BartleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Juvenile Bench Book (Complete)Dokument252 SeitenJuvenile Bench Book (Complete)cookjvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure RulesDokument7 SeitenCivil Procedure RulesTara ShaghafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michigan Governor's Child Abuse Task Force ModelDokument21 SeitenMichigan Governor's Child Abuse Task Force ModelBeverly TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 - 2 - II Removing Parental AuthorityDokument28 Seiten5 - 2 - II Removing Parental Authoritykapr1c0rnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forensic Psychology: Chapter OutlineDokument19 SeitenForensic Psychology: Chapter Outlineprerna9486Noch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint Adultery PDFDokument3 SeitenComplaint Adultery PDFBelners PadsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disability Benefits and Application File July 7, 2015 No Compression by HackersDokument66 SeitenDisability Benefits and Application File July 7, 2015 No Compression by HackersStan J. CaterboneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full List of RecipientsDokument28 SeitenFull List of RecipientsLive 5 NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Rights Petition: THE PEOPLE V THE OFFICERS OF THE USDokument335 SeitenHuman Rights Petition: THE PEOPLE V THE OFFICERS OF THE USSusanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Bond-Motion To Reduce Bond For The Jail Magistrate CouDokument5 SeitenBasic Bond-Motion To Reduce Bond For The Jail Magistrate CouJoshua SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insanity PleaDokument8 SeitenInsanity Pleaapi-545890787Noch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Roman G. Weninger, 624 F.2d 163, 10th Cir. (1980)Dokument8 SeitenUnited States v. Roman G. Weninger, 624 F.2d 163, 10th Cir. (1980)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Brenda Snipes v. Rick Scott - Notice of Constitutional Challenge of StatuteDokument4 SeitenBrenda Snipes v. Rick Scott - Notice of Constitutional Challenge of StatuteLegal InsurrectionNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Attorney's Duty To The Court Against Concealment, Nondisclosure and Suppression of Information As Coextensive With The Duty Not To Allow Fraud To Be Committed Upon The CourtDokument9 SeitenThe Attorney's Duty To The Court Against Concealment, Nondisclosure and Suppression of Information As Coextensive With The Duty Not To Allow Fraud To Be Committed Upon The Courtwhackz100% (1)

- An Attorney's Liability For The Negligent Infliction of Emotional DistressDokument19 SeitenAn Attorney's Liability For The Negligent Infliction of Emotional Distresswhackz100% (1)

- Subject Matter Jurisdiction As A New Issue On Appeal: Reining in An Unruly HorseDokument35 SeitenSubject Matter Jurisdiction As A New Issue On Appeal: Reining in An Unruly Horsewhackz100% (1)

- The True and Invisible Rosicrucian OrderDokument150 SeitenThe True and Invisible Rosicrucian Orderwhackz100% (2)

- The Role of Altered States of Consciousness in Native American HealingDokument11 SeitenThe Role of Altered States of Consciousness in Native American HealingwhackzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Natural Mind - Waking Up VOLUME ONEDokument682 SeitenThe Natural Mind - Waking Up VOLUME ONEOne Big ShiftNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chaos Magick - Phil Hine, PermutationsDokument40 SeitenChaos Magick - Phil Hine, PermutationsRaphael Ciribelly100% (1)

- Christopher Hyatt Undoing Yourself With Energized Meditation PDFDokument351 SeitenChristopher Hyatt Undoing Yourself With Energized Meditation PDFJoCxxxygen100% (4)

- Chaos Sorcery Hall NickDokument65 SeitenChaos Sorcery Hall NickIPDENVER96% (27)

- Shifting, Shamanism and TherianthropyDokument43 SeitenShifting, Shamanism and TherianthropyLupa100% (14)

- CHP Study Guide Level 1Dokument12 SeitenCHP Study Guide Level 1whackzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Western Sex MagicDokument125 SeitenWestern Sex Magicwhackz85% (39)

- Bloomberg Excel Desktop GuideDokument52 SeitenBloomberg Excel Desktop GuidepldevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hedge Fund Book V5Dokument133 SeitenHedge Fund Book V5whackz100% (3)

- The Ultimate Fanspeed Ic Nibitor GuideDokument11 SeitenThe Ultimate Fanspeed Ic Nibitor GuidewhackzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fermi Bios - Nibitor - Fermi Bios Editor GuideDokument12 SeitenFermi Bios - Nibitor - Fermi Bios Editor GuideMihai Marian CenusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Malpractice Damages in A Trial Within A Trial - A Critical Analysis of Unique Concepts: Areas of Unconscionability.Dokument36 SeitenLegal Malpractice Damages in A Trial Within A Trial - A Critical Analysis of Unique Concepts: Areas of Unconscionability.whackz100% (3)

- A Guide To Establishing A Hedge FundDokument44 SeitenA Guide To Establishing A Hedge FundwhackzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrolyte Disturbances Causes and ManagementDokument19 SeitenElectrolyte Disturbances Causes and Managementsuci triana putriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shock SepticDokument35 SeitenShock SepticAkbar SyarialNoch keine Bewertungen

- 209 (8) 6Dokument1 Seite209 (8) 6Rajesh DmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Amnesia ExplanationDokument2 SeitenAmnesia ExplanationMuslim NugrahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Injury Patterns in Danish Competitive SwimmingDokument5 SeitenInjury Patterns in Danish Competitive SwimmingSebastian VicolNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP 1activity Intolerance N C P BY BHERU LALDokument1 SeiteNCP 1activity Intolerance N C P BY BHERU LALBheru LalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Itls 9th Edition Prep Packet Advanced Provider VersionDokument19 SeitenItls 9th Edition Prep Packet Advanced Provider VersionUmidagha BaghirzadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phenylketonuria PkuDokument8 SeitenPhenylketonuria Pkuapi-426734065Noch keine Bewertungen

- Position PaperDokument8 SeitenPosition Paperapi-316749075Noch keine Bewertungen

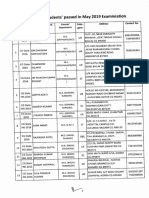

- List of PG Students' Passed in May 2019 ExaminiationDokument4 SeitenList of PG Students' Passed in May 2019 Examiniationyogesh kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- About DysphoriaDokument5 SeitenAbout DysphoriaCarolina GómezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dental HeadpieceDokument10 SeitenDental HeadpieceUnicorn DenmartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Internal Medicine Admission NoteDokument4 SeitenSample Internal Medicine Admission NoteMayer Rosenberg100% (8)

- Some Oncology Tips & Tricks by DR Khaled MagdyDokument8 SeitenSome Oncology Tips & Tricks by DR Khaled MagdyA.h.Murad100% (1)

- Case Reports in The Use of Vitamin C Based Regimen in Prophylaxis and Management of COVID-19 Among NigeriansDokument5 SeitenCase Reports in The Use of Vitamin C Based Regimen in Prophylaxis and Management of COVID-19 Among NigeriansAndi.Thafida KhalisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NMSRC Sample Research PaperDokument4 SeitenNMSRC Sample Research Paperjemma chayocasNoch keine Bewertungen

- FIT HW - Module 2Dokument34 SeitenFIT HW - Module 2Ivan Louis C. ARNOBITNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common Dermatology Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - 6Dokument3 SeitenCommon Dermatology Multiple Choice Questions and Answers - 6Atul Kumar Mishra100% (1)

- Caring For Children Receiving Chemotherapy, Antimicrobial Therapy and Long-Term Insulin TherapyDokument34 SeitenCaring For Children Receiving Chemotherapy, Antimicrobial Therapy and Long-Term Insulin TherapyRubinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Euros Core OrgDokument6 SeitenEuros Core OrgClaudio Walter VidelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Receta Medica InglesDokument2 SeitenReceta Medica InglesHannia RomeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 5. MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY EDUCATIONDokument7 SeitenTopic 5. MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY EDUCATIONSophia GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- OncologyDokument3 SeitenOncologyMichtropolisNoch keine Bewertungen

- So My Cat Has Chronic Kidney DiseaseDokument2 SeitenSo My Cat Has Chronic Kidney DiseaseNur Alisya Hasnul HadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthDokument4 SeitenMaternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthTiffani_Vanessa01Noch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetic NephropathyDokument10 SeitenDiabetic NephropathySindi Nabila PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 68 AdaptiveDokument17 Seiten68 AdaptiveAmit YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brittany 2Dokument4 SeitenBrittany 2Sharon Williams75% (4)

- 10 - Neonaticide, Infanticide and Child HomicideDokument45 Seiten10 - Neonaticide, Infanticide and Child HomicideWala AbdeljawadNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESHRE Guideline EndometriosisDokument27 SeitenESHRE Guideline EndometriosisRodiani MoekroniNoch keine Bewertungen