Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Civ Rev Digests Batch 1

Hochgeladen von

Biz Manzano ManzonCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Civ Rev Digests Batch 1

Hochgeladen von

Biz Manzano ManzonCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

TAADA VS.

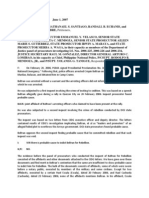

TUVERA FACTS: Petitioners seek a writ of mandamus to compel respondent public officials to publish, and/or cause the publication in the Official Gazette of various presidential decrees, letters of instructions, general orders, proclamations, executive orders, letters of implementation and administrative orders. Respondents, through the Solicitor General would have this case dismissed outright on the ground that petitioners have no legal personality or standing to bring the instant petition. The view is submitted that in the absence of any showing that the petitioner are personally and directly affected or prejudiced by the alleged non-publication of the presidential issuances in question. Respondent further contend that publication in the Official Gazette is not a sine qua non requirement for the effectivity of the law where the law themselves provides for their own effectivity dates. ISSUES: Whether the presidential decrees in question which contain special provisions as to the date they are to take effect, publication in the Official Gazette is not indispensable for their effectivity? RULING: Publication in the Official Gazette is necessary in those cases where the legislation itself does not provide for its effectivity date, for then the date of publication is material for determining its date of effectivity, which is the 15th day following its publication, but not when the law itself provides for the date when it goes into effect. Article 2 does not preclude the requirement of publication in the Official Gazette, even if the law itself provides for the date of its effectivity. The publication of all presidential issuances of a public nature or of general applicability is mandated by law. Obviously, presidential decrees that provide for fines, forfeitures or penalties for their violation or otherwise impose burdens on the people, such as tax revenue measures, fall within this category. Other presidential issuances which apply only to particular persons or class of persons such as administrative and executive orders need not be published on the assumption that they have been circularized to all concern. The Court therefore declares that presidential issuances of general application, which have not been published, shall have no force and effect. FUENTES vs ROCA

Facts: -Sabina Tarrozza owned a titled 358-square meter lot in Zamboanga City. Later on, she sold the same to her son Tarciano Roca under a deed of absolute sale, meanwhile, the latter has failed to register the same. After 6 years, Tarciano offered the lot to the petitioners (Fuentes spouses). An agreement to sell prepared by Atty. Plagata, among others was thereafter signed by the parties, which agreement expressly stated that it was to take effect in six months. -Several conditions were required by such agreement, among others was that within 6 months Tarciano was to clear the lot of structures and occupants and secure the consent of his estranged wife, Rosario Roca to the sale. -As soon as Tarciano has met the other conditions, Atty. Plagata notarized Rosarios affidavit in Zamboanga, thereafter, a deed of absolute sale was executed in favor of the Fuentes spouses. A new title was issued in favor of the spouses who constructed a building on the lot. -In 1997, 8 years after Tarciano and Rosario passed away, their children, together with Tarcianos sister who was represented by her son, filed an action for the annulment of sale and reconveyance of the land against the Fuentes spouses before the RTC of Zamboanga on the ground that the sale was void for Rosarios consent was not secured and her signature on the affidavit was forged. -However the Fuentes spouses argued that the claim of forgery was personal to Rosario and she alone could invoke it and that the 4 year prescriptive period for nullifying the sale on ground of fraud had already lapsed. -RTC- dismissed the case on the ground of prescription CA- reversed the RTCs decision and found sufficient evidence of forgery and that since Tarciano and Rosario had been living separately for 30 years since 1958, it also reinforced the conclusion that her signature had been forged. Issue: Whether or not the Rocas action for the declaration of nullity of that sale to the spouses already prescribed? Held: Contrary to the ruling of the Court of Appeals, the law that applies to this case is the Family Code, not

the Civil Code. Although Tarciano and Rosario got married in 1950, Tarciano sold the conjugal property to the Fuentes spouses on January 11, 1989, a few months after the Family Code took effect on August 3, 1988. When Tarciano married Rosario, the Civil Code put in place the system of conjugal partnership of gains on their property relations. While its Article 165 made Tarciano the sole administrator of the conjugal partnership, Article 166 prohibited him from selling commonly owned real property without his wifes consent. Still, if he sold the same without his wifes consent, the sale is not void but merely voidable. Article 173 gave Rosario the right to have the sale annulled during the marriage within ten years from the date of the sale. Failing in that, she or her heirs may demand, after dissolution of the marriage, only the value of the property that Tarciano fraudulently sold. However, the Family Code took effect on August 3, 1988. Its Chapter 4 on Conjugal Partnership of Gains expressly superseded Title VI, Book I of the Civil Code on Property Relations Between Husband and Wife. Further, the Family Code provisions were also made to apply to already existing conjugal partnerships without prejudice to vested rights. Consequently, when Tarciano sold the conjugal lot to the Fuentes spouses on January 11, 1989, the law that governed the disposal of that lot was already the Family Code. In contrast to Article 173 of the Civil Code, Article 124 of the Family Code does not provide a period within which the wife who gave no consent may assail her husbands sale of the real property. It simply provides that without the other spouses written consent or a court order allowing the sale, the same would be void. But, although a void contract has no legal effects even if no action is taken to set it aside, when any of its terms have been performed, an action to declare its inexistence is necessary to allow restitution of what has been given under it. This action, according to Article 1410 of the Civil Code does not prescribe. Here, the Rocas filed an action against the Fuentes spouses in 1997 for annulment of sale and reconveyance of the real property that Tarciano sold without his wifes written consent. The passage of time did not erode the right to bring such an action. Petition is denied and the CA decision is affirmed with modification directing respondents Roca to pay petitioner spouses Manuel and Leticia Fuentes the P200,000.00 that the latter paid Tarciano T. Roca,

with legal interest from January 11, 1989 until fully paid, chargeable against his estate and to indemnify petitioner spouses Manuel and Leticia Fuentes with their expenses for introducing useful improvements on the subject land or pay the increase in value which it may have acquired by reason of those improvements, with the spouses entitled to the right of retention of the land until the indemnity is made. COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS vs HYPERMIX On 7 November 2003, petitioner Commissioner of Customs issued Memorandum CMO 27-2003. Wheat was classified according to the following: (1) importer or consignee; (2) country of origin; and (3) port of discharge. Depending on these factors, wheat would be classified either as food grade or feed grade. The corresponding tariff for food grade wheat was 3%, for feed grade, 7%. Respondent filed a Petition for Declaratory Relief with the (RTC) of Las Pias City. Respondent contended that CMO 27-2003 was issued without following the mandate of the Revised Administrative Code on public participation, prior notice, and publication or registration with the University of the Philippines Law Center. Respondent also alleged that the regulation summarily adjudged it to be a feed grade supplier without the benefit of prior assessment and examination; thus, despite having imported food grade wheat, it would be subjected to the 7% tariff upon the arrival of the shipment, forcing them to pay 133% more than was proper. TC = ruled in favor of respondent. Trial court found that petitioners had not followed the basic requirements of hearing and publication in the issuance of CMO 27-2003. The appellate court, dismissed the appeal. W/N the basic requirements of hearing & publication was observed? SC = NO. Considering that the questioned regulation would affect the substantive rights of respondent, it therefore follows that petitioners should have applied the pertinent provisions of Book VII, Chapter 2 of the Revised Administrative Code, to wit: Section 3. Filing. (1) Every agency shall file with the University of the Philippines Law Center three (3) certified copies of every rule adopted by it. Rules in force on the date of effectivity of this Code which are not filed within three (3) months from that date shall not thereafter be the bases of any sanction against any party of persons. xxx xxx xxx

Section 9. Public Participation. - (1) If not otherwise required by law, an agency shall, as far as practicable, publish or circulate notices of proposed rules and afford interested parties the opportunity to submit their views prior to the adoption of any rule. (2) In the fixing of rates, no rule or final order shall be valid unless the proposed rates shall have been published in a newspaper of general circulation at least two (2) weeks before the first hearing thereon. (3) In case of opposition, the rules on contested cases shall be observed. When an administrative rule is merely interpretative in nature, its applicability needs nothing further than its bare issuance, for it gives no real consequence more than what the law itself has already prescribed. When the administrative rule goes beyond merely providing for the means that can facilitate or render least cumbersome the implementation of the law but substantially increases the burden of those governed, it behooves the agency to accord at least to those directly affected a chance to be heard, and thereafter to be duly informed, before that new issuance is given the force and effect of law. Because petitioners failed to follow the requirements enumerated by the Revised Administrative Code, the assailed regulation must be struck down. In summary, petitioners violated respondents right to due process in the issuance of CMO 27-2003 when they failed to observe the requirements under the Revised Administrative Code. Petition is DENIED. KASILAG vs RODRIGUEZ PROCEDURAL FACTS: This is an appeal taken by the defendant-petitioner from the decision of the Court of Appeals which modified that rendered by the court of First Instance of Bataan. The said court held: that the contract is entirely null and void and without effect; that the plaintiffs-respondents, then appellants, are the owners of the disputed land, with its improvements, in common ownership with their brother Gavino Rodriguez, hence, they are entitled to the possession thereof; that the defendant-petitioner should yield possession of the land in their favor, with all the improvements thereon and free from any lien SUBSTANTIVE FACTS: The parties entered into a contract of loan to which has an accompanying accessory contract of mortgage. The executed accessory contract involved the improvements on a piece land, the land having been acquired by means of homestead. P for his part accepted the contract of mortgage.

Believing that there are no violations to the prohibitions in the alienation of lands P, acting in good faith took possession of the land. To wit, the P has no knowledge that the enjoyment of the fruits of the land is an element of the credit transaction of Antichresis. ISSUE: Whether or not P is deemed to be a possessor in good faith of the land, based upon Article 3 of the New Civil Code as states Ignorance of the law excuses no one from compliance therewith, the Ps lack of knowledge of the contract of antichresis. HELD: The accessory contract of mortgage of the improvements of on the land is valid. The verbal contract of antichresis agreed upon is deemed null and void. RATIO: Sec 433 of the Civil Code of the Philippines provides Every person who is unaware of any flaw in his title or in the manner of its acquisition by which it is invalidated shall be deemed a possessor of good faith. And in this case, the petitioner acted in good faith. Good faith maybe a basis of excusable ignorance of the law, the petitioner acted in good faith in his enjoyment of the fruits of the land to which was done through his apparent acquisition thereof. DIGEST 2 FACTS: May 16, 1932: Emiliana Ambrosio, owner of a 6.7540 ha land in Limay, Bataan, encumbers the improvements on the said land under mortgage for P1000 and payable to Gavino Rodriguez. The said amount is due after 4 years or on November 16, 1938 with 12% interest per annum, to render the said mortgage null and void. Upon Emilianas failure to pay for the stipulated interest and tax on the land and its improvements, both parties entered into a verbal agreement wherein Emiliana conveyed to Gavino possession of the land by agreeing to no longer collect interest on the loan, pay the land tax, enjoy improvements on the land and introduce improvements on it. ISSUE: Whether or not Gavino Kasilag should be considered a possessor of the land in good faith all the while being ignorant of the law of antichresis? HELD: Affirmative. Gavino Rodriguez, the petitioner, is deemed a possessor in good faith. RATIO: *Good faith as basis for excusable ignorance Mr. Rodriguezs acceptance of the mortgage of the improvements firmly believed that he was not violating prohibition regarding alienation of the land,

and his was ignorant of his consent to possession and enjoyment of the land constituted a contract of atichresis. Article 433 of the Civil Code defines a possessor in good faith who is unaware of any flaw in his title, or in the manner of its acquisition, by which it is invalidated. ELEGADO vs CA FACTS: Warren Taylor Graham, an American national formerly resident in the Philippines, died in Oregon, his son, Ward Graham, filed an estate tax return with the Philippine Revenue Representative in U.S.A. Commissioner of Internal Revenue assessed the decedent's estate an estate tax in the amount of P96,509.35 which was protested by the law firm of Bump, Young and Walker, a foreign law firm, on behalf of the estate. The protest was denied and no further action was taken by the estate in pursuit of that protest. Meanwhile, the decedent's will had been admitted to probate in the Circuit Court of Oregon. Ward Graham, the designated executor, then appointed Ildefonso Elegado as his attorney-in-fact for the allowance of the will in the Philippines, which was eventually allowed with the petitioner as ancillary administrator. As such, he filed a second estate tax return with the BIR. The Commissioner imposed an assessment on the estate in a lower amount of P72,948.87, which was also protested to by the Agrava, Lucero and Gineta Law Office, This time a domestic law firm, on behalf of the estate. Later, the Commissioner filed in the probate proceedings a motion for the allowance of the basic estate tax of P96,509.35 (the first assessment), stating that this liability had not yet been paid although the assessment had long become final and executory. Elegado regarded this motion as an implied denial of the protest filed against the second assessment, and actig on this belief, he filed a petition for review with the Court of Tax Appeals challenging the said assessment. The Commissioner in the end instead cancelled the second protested assessment in a letter to the decedent's estate, which was notified to the Court of Tax Appeals in a motion to dismiss on the ground that the protest had become moot and academic. The motion was granted and the petition dismissed, hence this petition. ISSUE: Whether the appeal filed with the respondent court should be allowed on the ground that the first

assessment is not final and executory because it was based on a return filed by foreign lawyers who had no knowledge of our tax laws HELD: Hells NO. Petition is DENIED, with costs against the petitioner. RATIO: Since no appeal was made within the regulatory period, the same has become final. The petitioner no longer has a cause of action as can be seen from the express cancellation of the second assessment as it was precisely from this assessment that he was appealing. The said assessment had been cancelled by virtue of the letter. The respondent court was on surer ground when it followed with the finding that the said cancellation had rendered the petition moot and academic. There was really no more assessment to review. The petitioner argues that the first assessment is not binding on him because it was based on a return filed by foreign lawyers who had no knowledge of our tax laws or access to the Court of Tax Appeals. The petitioner is clutching at straws. The petitioner cannot be serious when he argues that the first assessment was invalid because the foreign lawyers who filed the return on which it was based were not familiar with our tax laws and procedure. Is the petitioner suggesting that they are excused from compliance therewith because of their ignorance? If our own lawyers and taxpayers cannot claim a similar preference because they are not allowed to claim a like ignorance, it stands to reason that foreigners cannot be any less bound by our own laws in our own country. A more obvious and shallow discrimination than that suggested by the petitioner is indeed difficult to find. As no further action was taken thereon by the decedent's estate, there is no question that the assessment has become final and executory. In view of the finality of the first assessment, the petitioner cannot now raise the question of its validity before this Court any more than he could have done so before the Court of Tax Appeals. What the estate of the decedent should have done earlier, following the denial of its protest on July 7, 1978, was to appeal to the Court of Tax Appeals within the reglementary period of 30 days after it received notice of said denial. It was in such appeal that the petitioner could then have raised the first two issues he now raises without basis in the present petition. The assessment being no longer controversial or renewable, there was no justification for the

respondent court to rule on the petition except to dismiss it. CABALIT vs COA

Ombudsman. Petitioners sought reconsideration of the CA decision, but the CA denied their motions. ISSUES: Whether or not

FACTS: The Philippine Star News (Cebu City) reported that LTO employees in Jagna, Bohol are shortchanging the government by tampering with their income reports. State Auditors Teodocio D. Cabalit and Emmanuel L. Coloma of the Provincial Revenue Audit Group conducted an investigation. Tampering of official receipts of Motor Vehicle Registration during the years 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001 was then discovered by the investigators and a total of 106 receipts were tampered. The difference between the amounts paid by the vehicle owners and the amounts appearing on the file copies were pocketed by the perpetrators and only the lower amounts appearing on the retained duplicate file copies were reported in the Report of Collections. The scheme was perpetrated by LTO employees Leonardo G. Olaivar, Gemma P. Cabalit, Filadelfo S. Apit and Samuel T. Alabat, and resulted in an unreported income totaling P169,642.50. A formal charge for dishonesty was filed against Olaivar, Cabalit, Apit and Alabat before the Office of the Ombudsman-Visayas. Olaivar, Cabalit, Apit and Alabat submitted separate counter-affidavits, all essentially denying knowledge and responsibility for the anomalies. On February 12, 2004, the Office of the Ombudsman-Visayas directed the parties to submit their position papers pursuant to A.O. No. 17, dated September 7, 2003, amending the Rules of Procedure of the Office of the Ombudsman. No cross-examination of State Auditor Cabalit was conducted. The Office of the Ombudsman-Visayas found petitioners liable for dishonesty for tampering the official receipts to make it appear that they collected lesser amounts than they actually collected. Petitioners sought reconsideration of the decision, but their motions were denied by the Ombudsman. Thus, they separately sought recourse from the CA. The CA dismissed the petitions and affirmed with modification the findings of the (1) There was a violation of the right to due process when the hearing officer at the Office of the Ombudsman-Visayas adopted the procedure under A.O. No. 17 notwithstanding the fact that the amendatory order took effect after the hearings had started (2) Cabalit, Apit and Olaivar are administratively liable RULING: (1) No, the petitioners were not denied due process of law because they were afforded every opportunity to defend themselves by allowing them to submit counter-affidavits, position papers, memoranda and other evidence in their defense. They cannot rightfully complain that they were denied due process of law. Section 5(b)(1) Rule 3, of the Rules of Procedure of the Office of the Ombudsman, as amended by A.O. No. 17, plainly provides that the hearing officer may issue an order directing the parties to file, within ten days from receipt of the order, their respective verified position papers on the basis of which the hearing officer may consider the case submitted for decision. It is only when the hearing officer determines that based on the evidence, there is a need to conduct clarificatory hearings or formal investigations under Section 5(b)(2) and Section 5(b)(3) that such further proceedings will be conducted. But the determination of the necessity for further proceedings rests on the sound discretion of the hearing officer. Petitioners failed to show any cogent reason why the hearing officers determination should be overturned, the determination will not be disturbed by the Court. There is no merit in their contention that the new procedures under A.O. No. 17, which took effect while the case was already undergoing trial before the

hearing officer, should not have been applied. One does not have a vested right in procedural rules. In Tan, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, the Court elucidated: Statutes regulating the procedure of the courts will be construed as applicable to actions pending and undetermined at the time of their passage. Procedural laws are retroactive in that sense and to that extent. The fact that procedural statutes may somehow affect the litigants rights may not preclude their retroactive application to pending actions. The retroactive application of procedural laws is not violative of any right of a person who may feel that he is adversely affected. Nor is the retroactive application of procedural statutes constitutionally objectionable. The reason is that as a general rule no vested right may attach to, nor arise from, procedural laws. It has been held that a person has no vested right in any particular remedy, and a litigant cannot insist on the application to the trial of his case, whether civil or criminal, of any other than the existing rules of procedure. The rule admits of certain exceptions, as (a) when the statute itself expressly or by necessary implication provides that pending actions are excepted from its operation or (b) where to apply it would impair vested rights. However, petitioners failed to show that application of A.O. No. 17 to their case would cause injustice to them. There is no merit to Cabalits assertion that she should have been investigated under the old rules of procedure of the Office of the Ombudsman. In Marohomsalic v. Cole, we clarified that the Office of the Ombudsman has only one set of rules of procedure and that is A.O. No. 07, series of 1990, as

amended. There have been various amendments made but it has remained, to date, the only set of rules of procedure governing cases filed in the Office of the Ombudsman. Hence, the phrase as amended is correctly appended to A.O. No. 7 every time it is invoked. A.O. No. 17 is just one example of these amendments. (2) Only questions of law may be brought by the parties and passed upon by the Court in the exercise of its power to review. The Court recognizes the expertise and independence of the Ombudsman and will avoid interfering with its findings absent a finding of grave abuse of discretion. Hence, being supported by substantial evidence, the Court found no reason to disturb the factual findings of the Ombudsman which are affirmed by the CA. WHEREFORE, the petitions for review on certiorari are DENIED. The assailed Decision dated January 18, 2006 and Resolution dated September 21, 2007 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP. Nos. 86256, 86394 and 00047 are AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION. Petitioner Leonardo G. Olaivar is held administratively liable for DISHONESTY and meted the penalty of dismissal from the service as well as the accessory penalties inherent to said penalty. REPUBLIC vs GRANADA Yolanda Cadacio Granada and Cyrus Granada got married in 1993. In 1994 Cyrus went to Taiwan to seek employment. Yolanda claimed that from that time she had not received any communication from her husband notwithstanding efforts to locate him. Her brother testified that he had asked Cyrus relatives regarding the latters whereabouts, to no avail. 9 years later, Yolanda filed a petition to have Cyrus declared presumptively dead. RTC rendered a decision declaring him presumptively dead. The OSG filed an MR that Yolanda failed to exert earnest efforts to locate Cyrus and thus failed to prove her well-founded belief that he was already dead. RTC denied MR. Petitioner filed a notice of appeal to elevate the case to the CA. Yolanda filed an MTD for lack of jurisdiction declaration of presumptive death under rule 41 of the FC is a summary proceeding thus the judgment thereon is immediately final and executor. CA granted the MTD.

ISSUE: WON the CA erred in granting the MTD on the ground that the decision of the RTC in a summary proceeding for the declaration of presumptive death is immediately final and executory hence not subject to appeal. NO. In Republic v. Bermudez-Lorino,[6] the Republic likewise appealed the CAs affirmation of the RTCs grant of respondents Petition for Declaration of Presumptive Death of her absent spouse. The Court therein held that it was an error for the Republic to file a Notice of Appeal when the latter elevated the matter to the CA. In the present case, the Republic argues that Bermudez-Lorino has been superseded by the subsequent Decision of the Court in Republic v. Jomoc,[7] issued a few months later. In Jomoc, the RTC granted respondents Petition for Declaration of Presumptive Death of her absent husband for the purpose of remarriage. Petitioner Republic appealed the RTC Decision by filing a Notice of Appeal. The trial court disapproved the Notice of Appeal on the ground that, under the Rules of Court,[8] a record on appeal is required to be filed when appealing special proceedings cases. The CA affirmed the RTC ruling. In reversing the CA, this Court clarified that while an action for declaration of death or absence under Rule 72, Section 1(m), expressly falls under the category of special proceedings, a petition for declaration of presumptive death under Article 41 of the Family Code is a summary proceeding, as provided for by Article 238 of the same Code. Since its purpose was to enable her to contract a subsequent valid marriage, petitioners action was a summary proceeding based on Article 41 of the Family Code, rather than a special proceeding under Rule 72 of the Rules of Court. Considering that this action was not a special proceeding, petitioner was not required to file a record on appeal when it appealed the RTC Decision to the CA. We do not agree with the Republics argument that Republic v. Jomoc superseded our ruling in Republic v. Bermudez-Lorino. As observed by the CA, the Supreme Court in Jomoc did not expound on the characteristics of a summary proceeding under the Family Code. In contrast, the Court in BermudezLorino expressly stated that its ruling on the impropriety of an ordinary appeal as a vehicle for questioning the trial courts Decision in a summary proceeding for declaration of presumptive death under Article 41 of the Family Code was intended to set the records straight and for the future guidance of the bench and the bar.

At any rate, four years after Jomoc, this Court settled the rule regarding appeal of judgments rendered in summary proceedings under the Family Code when it ruled Republic v. Tango: In sum, under Article 41 of the Family Code, the losing party in a summary proceeding for the declaration of presumptive death may file a petition for certiorari with the CA on the ground that, in rendering judgment thereon, the trial court committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction. From the decision of the CA, the aggrieved party may elevate the matter to this Court via a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court. NOTE: Sorry ang gulo. I think it is about RoC v. FC regarding presumptive death. ACCENTURE vs COMMISSIONER Facts: On July 2004, petitioner Accenture filed with the Department of Finance (DoF) an administrative claim for refund or issuance of a Tax Credit Certificate (in the amount of P35,178,844.21) for having excess or unutilized input VAT credits earned from its zero-rated transactions. DoF did not act on the claim. On August 2004, Petitioner filed a Petition for Review with the First Division of the Court of Tax Appeals. CIR argued that (1) Sale by Accenture of goods and services to its clients are not zero-rated transactions, (2) Claims for refund are construed strictly against the claimant and petitioner has failed to prove that it is entitled to a refund, because its claim has not been fully substantiated or documented. On November 2008, Division denied the petition. It ruled that petitioner failed to present evidence to prove that its foreign clients did business outside the Philippines. It further ruled that petitioners services would qualify for zero-rating under the 1997 NIRC only if recipient of the services was doing business outside the Philippines. Division cited the January 2007 case of Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Burmeister as basis. On Motion for Reconsideration, petitioner argued, among others, that Burmeister, having been promulgated on January 22, 2007 (after petitioner filed with the division) cannot be made to apply to its case, MR was denied. On appeal, CTA En Banc concluded that petitioner failed to discharge the burden of proving the allegation that its clients were foreign-based. Accenture filed a Petition for Review with the CTA En Banc, but it only further affirmed the Divisions Decision and Resolution. Issue: Whether or not the CTA can apply the Burmeister case, even when petitioner had filed

before the aforementioned case was even promulgated. Held: The Court stated that even though Accentures Petition was filed before Burmeister was promulgated, the pronouncements made in the said case may be applied to the case at bar without violating the rule against retroactive application. When the Court decides a case, it does not pass a new law, but merely interprets a pre-existing one. When the Court interpreted Section 102(b) of the 1977 Tax Code in Burmeister, the interpretation became part of the law from the moment abait became effective. The Court also stated that an interpretation of Section 102(b) of the 1977 Tax Code is an interpretation of Section 108 of the 1997 Tax Code, the latter being a mere reproduction of the former. The Court upheld the Decision of the CTA En Banc, concluding that petitioner failed to prove that its clients were doing business outside the Philippines, and merely presented evidence that its clients were foreign entities. UP vs DIZON Facts: On August 30, 1990, the UP, through its then President Jose V. Abueva, entered into a General Construction Agreement with respondent Stern Builders for the construction of the extension building and the renovation of the College of Arts and Sciences Building in the campus of the University of the Philippines in Los Baos (UPLB). In the course of the implementation of the contract, Stern Builders submitted three progress billings corresponding to the work accomplished, but the UP paid only two of the billings. The third billing was not paid due to its disallowance by the Commission on Audit (COA). Despite the lifting of the disallowance, the UP failed to pay the billing, prompting Stern Builders to sue the UP and its corespondent officials to collect the unpaid billing and to recover various damages. After trial, on November 28, 2001, the RTC rendered its decision in favor of the plaintiffs. Following the RTCs denial of its motion for reconsideration on May 7, 2002, the UP filed a notice of appeal on June 3, 2002. Stern Builders opposed the notice of appeal on the ground of its filing being belated, and moved for the execution of the decision. The UP countered that the notice of appeal was filed within the reglementary period because the UPs Office of Legal Affairs (OLS) in Diliman, Quezon City received the order of denial only on May 31, 2002. On September 26, 2002, the RTC denied due course to the notice of appeal for having been filed

out of time and granted the private respondents motion for execution. The RTC issued the writ of execution on October 4, 2002, and the sheriff of the RTC served the writ of execution and notice of demand upon the UP, through its counsel, on October 9, 2002. The UP filed an urgent motion to reconsider the order dated September 26, 2002, to quash the writ of execution dated October 4, 2002, and to restrain the proceedings. However, the RTC denied the urgent motion on April 1, 2003. On June 24, 2003, the UP assailed the denial of due course to its appeal through a petition for certiorari in the Court of Appeals (CA). On February 24, 2004, the CA dismissed the petition for certiorari upon finding that the UPs notice of appeal had been filed late. The UP sought a reconsideration, but the CA denied the UPs motion for reconsideration on April 19, 2004. On May 11, 2004, the UP appealed to the Court by petition for review on certiorari. On June 23, 2004, the Court denied the petition for review. The UP moved for the reconsideration of the denial of its petition for review on August 29, 2004, but the Court denied the motion on October 6, 2004. The denial became final and executory on November 12, 2004. Issue: Whether or not the fresh period rule announced in Neypes v. CA can be given retroactive application? Held: Firstly, the service of the denial of the motion for reconsideration upon Atty. Nolasco of the UPLB Legal Office was invalid and ineffectual because he was admittedly not the counsel of record of the UP. The rule is that it is on the counsel and not the client that the service should be made. That counsel was the OLS in Diliman, Quezon City, which was served with the denial only on May 31, 2002. As such, the running of the remaining period of six days resumed only on June 1, 2002, rendering the filing of the UPs notice of appeal on June 3, 2002 timely and well within the remaining days of the UPs period to appeal. Secondly, even assuming that the service upon Atty. Nolasco was valid and effective, such that the remaining period for the UP to take a timely appeal would end by May 23, 2002, it would still not be correct to find that the judgment of the RTC became final and immutable thereafter due to the notice of appeal being filed too late on June 3, 2002. In so declaring the judgment of the RTC as final against the UP, the CA and the RTC applied the rule contained in the second paragraph of Section 3, Rule 41 of the Rules of Court to the effect that the filing of a motion for reconsideration interrupted the running of the period for filing the appeal; and that the period

resumed upon notice of the denial of the motion for reconsideration. For that reason, the CA and the RTC might not be taken to task for strictly adhering to the rule then prevailing. However, equity calls for the retroactive application in the UPs favor of the fresh-period rule that the Court first announced in mid-September of 2005 through its ruling in Neypes v. Court of Appeals, viz: To standardize the appeal periods provided in the Rules and to afford litigants fair opportunity to appeal their cases, the Court deems it practical to allow a fresh period of 15 days within which to file the notice of appeal in the Regional Trial Court, counted from receipt of the order dismissing a motion for a new trial or motion for reconsideration. The retroactive application of the fresh-period rule, a procedural law that aims "to regiment or make the appeal period uniform, to be counted from receipt of the order denying the motion for new trial, motion for reconsideration (whether full or partial) or any final order or resolution," is impervious to any serious challenge. This is because there are no vested rights in rules of procedure. xxx We have further said that a procedural rule that is amended for the benefit of litigants in furtherance of the administration of justice shall be retroactively applied to likewise favor actions then pending, as equity delights in equality. xxx It is cogent to add in this regard that to deny the benefit of the fresh-period rule to the UP would amount to injustice and absurdity injustice, because the judgment in question was issued on November 28, 2001 as compared to the judgment in Neypes that was rendered in 1998; absurdity, because parties receiving notices of judgment and final orders issued in the year 1998 would enjoy the benefit of the freshperiod rule but the later rulings of the lower courts like that herein would not. PERT/CPM vs VINUYA Facts: Complainants alleged that the agency deployed them to work as aluminum fabricator/installer in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. The respondents employment contracts,4provided for a two-year employment, nine hours a day, salary of 1,350 AED with overtime pay, food allowance, free and suitable housing (four to a room), free transportation, free laundry, and free medical and dental services.

Modern Metal gave the respondents, except Era, appointment letters6 Under the letters of appointment, their employment was increased to three years. The respondents claimed that they were shocked to find out what their working and living conditions were in Dubai. They called up the agency and complained about their predicament. The agency assured them that their concerns would be promptly addressed, but nothing happened. The respondents expressed to Modern Metal their desire to resign. Out of fear, as they put it, that Modern Metal would not give them their salaries and release papers, the respondents, except Era, cited personal/family problems for their resignation.8 Era mentioned the real reason "because I dont (sic) want the company policy"9 for his resignation. For its part, the agency countered that the respondents were not illegally dismissed; they voluntarily resigned from their employment to seek a better paying job. It claimed that the respondents, while still working for Modern Metal, applied with another company which offered them a higher pay. Unfortunately, their supposed employment failed to materialize and they had to go home because they had already resigned from Modern Metal. Labor Arbiter Ligerio V. Ancheta rendered a Decision10 dismissing the complaint, finding that the respondents voluntarily resigned from their jobs. The agency moved for reconsideration, contending that the appeal was never perfected and that the NLRC gravely abused its discretion in reversing the labor arbiters decision. The respondents, on the other hand, moved for partial reconsideration, maintaining that their salaries should have covered the unexpired portion of their employment contracts, pursuant to the Courts ruling in Serrano v. Gallant Maritime Services, Inc.13 The NLRC denied the agencys motion for reconsideration, but granted the respondents motion.14 It sustained the respondents argument that the award needed to be adjusted, particularly in relation to the payment of their salaries, consistent with the Courts ruling in Serrano. The ruling declared unconstitutional the clause, "or for three (3) months for every year of the unexpired term, whichever is less," in Section 10, paragraph 5, of R.A. 8042, limiting the entitlement of illegally

dismissed overseas Filipino workers to their salaries for the unexpired term of their contract or three months, whichever is less. CA dismissed the petition for lack of merit.16 It upheld the NLRC ruling that the respondents were illegally dismissed. The respondents maintain that since they were illegally dismissed, the CA was correct in upholding the NLRCs award of their salaries for the unexpired portion of their employment contracts, as enunciated in Serrano. They point out that the Serrano ruling is curative and remedial in nature and, as such, should be given retroactive application as the Court declared in Yap v. Thenamaris Ships Management.26 Further, the respondents take exception to the agencys contention that the Serrano ruling cannot, in any event, be applied in the present case in view of the enactment of R.A. 10022 on March 8, 2010, amending Section 10 of R.A. 8042. The amendment restored the subject clause in paragraph 5, Section 10 of R.A. 8042 which was struck down as unconstitutional in Serrano. The agency posits that the Serrano ruling has no application in the present case for three reasons. First, the respondents were not illegally dismissed and, therefore, were not entitled to their money claims. Second, the respondents filed the complaint in 2007, while the Serrano ruling came out on March 24, 2009. The ruling cannot be given retroactive application. Third, R.A. 10022, which was enacted on March 8, 2010 and which amended R.A. 8042, restored the subject clause in Section 10 of R.A. 8042, declared unconstitutional by the Court. Issue: Whether the CA erred in affirming the NLRCs award to the respondents of their salaries for the unexpired portion of their employment contracts, pursuant to the Serrano ruling. Held: The agency posits that in any event, the Serrano ruling has been nullified by R.A. No. 10022, entitled "An Act Amending Republic Act No. 8042, Otherwise Known as the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act of 1995, As Amended, Further Improving the Standard of Protection and Promotion of the Welfare of Migrant Workers, Their Families and Overseas Filipinos in Distress, and For Other Purposes."51 It argues that R.A. 10022, which lapsed into law (without the Signature of the

President) on March 8, 2010, restored the subject clause in the 5th paragraph, Section 10 of R.A. 8042. The amendment, contained in Section 7 of R.A. 10022, reads as follows: In case of termination of overseas employment without just, valid or authorized cause as defined by law or contract, or any unauthorized deductions from the migrant workers salary, the worker shall be entitled to the full reimbursement "of" his placement fee and the deductions made with interest at twelve percent (12%) per annum, plus his salaries for the unexpired portion of his employment contract or for three (3) months for every year of the unexpired term, whichever is less.52 (emphasis ours) This argument fails to persuade us. Laws shall have no retroactive effect, unless the contrary is provided.53 By its very nature, the amendment introduced by R.A. 10022 restoring a provision of R.A. 8042 declared unconstitutional cannot be given retroactive effect, not only because there is no express declaration of retroactivity in the law, but because retroactive application will result in an impairment of a right that had accrued to the respondents by virtue of the Serrano ruling entitlement to their salaries for the unexpired portion of their employment contracts. All statutes are to be construed as having only a prospective application, unless the purpose and intention of the legislature to give them a retrospective effect are expressly declared or are necessarily implied from the language used.54 We thus see no reason to nullity the application of the Serrano ruling in the present case. Whether or not R.A. 1 0022 is constitutional is not for us to rule upon in the present case as this is an issue that is not squarely before us. In other words, this is an issue that awaits its proper day in court; in the meanwhile, we make no pronouncement on it. WHEREFORE, premises considered, the petition is DENIED. The assailed Decision dated May 9, 2011 and the Resolution dated June 23, 2011 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 114353 are AFFIRMED. Let this Decision be brought to the attention of the Honorable Secretary of Labor and Employment and the Administrator of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration as a black mark in the deployment record of petitioner Pert/CPM Manpower Exponent Co., Inc., and as a record that should be considered in any similar future violations. NERWIN vs PNOC

FACTS: 1. In 1999, the National Electrification Administration ("NEA") published an invitation to pre-qualify and to bid for a contract, (IPB No. 80), for the supply and delivery of about 60,000 pieces of woodpoles and 20,000 pieces of crossarms needed in the country's Rural Electrification Project. 2. The said contract consisted of four components, namely: PIA, PIB and PIC or woodpoles and P3 or crossarms, necessary for NEA's projected allocation for Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao. 3. In response to the said invitation, bidders, such as private respondent [Nerwin], were required to submit their application for eligibility together with their technical proposals. At the same time, they were informed that only those who would pass the standard pre-qualification would be invited to submit their financial bids. 4. Only four bidders, including private respondent Nerwin, qualified to participate in the bidding for the IPB-80 contract. 5. Qualified bidders submitted their financial bids where private respondent [Nerwin] emerged as the lowest bidder for all schedules/components of the contract. 6. NEA then conducted a pre-award inspection of private respondent's [Nerwin's] manufacturing plants and facilities, including its identified supplier in Malaysia, to determine its capability to supply and deliver NEA's requirements. 7. In the Recommendation of Award for Schedules PIA, PIB, PIC and P3 IBP No. 80 [for the] Supply and Delivery of Woodpoles and Crossarms, the NEA administrator recommended to NEA's Board of Directors the approval of award to private respondent [Nerwin] of all schedules for IBP No. 80 8. However, NEA's Board of Directors passed Resolution No. 32 reducing by 50% the material requirements for IBP No. 80 "given the time limitations for the delivery of the materials. Private respondent [Nerwin] protested the said 50% reduction, alleging that the same was a ploy to accommodate a losing bidder. 9. On the other hand, the losing bidders Tri State and Pacific Synnergy appeared to have filed a complaint, citing alleged false or falsified documents submitted during the

pre-qualification stage which led to the award of the IBP-80 project to private respondent [Nerwin]. 10. Finding a way to nullify the result of the previous bidding, NEA officials sought the opinion of the Government Corporate Counsel who, among others, upheld the eligibility and qualification of private respondent [Nerwin]. Dissatisfied, the said officials attempted to seek a revision of the earlier opinion but the Government Corporate Counsel declared anew that there was no legal impediment to prevent the award of IPB-80 contract to private respondent [Nerwin]. 11. Notwithstanding, NEA allegedly held negotiations with other bidders relative to the IPB-80 contract, prompting private respondent [Nerwin] to file a complaint for specific performance with prayer for the issuance of an injunction, which injunctive application was granted. 12. PNOC-Energy Development Corporation purporting to be under the Department of Energy, issued Requisition No. FGJ 30904R1 or an invitation to pre-qualify and to bid for wooden poles needed for its Samar Rural Electrification Project (O-ILAW PROJECT) 13. Upon learning of the issuance of requistion for the O-ILAW Project, Nerwin filed a civil action in the RTC against PNOC-Energy Development Corporation and Ester R. Guerzon, as Chairman, Bids and Awards Committee, alleging that requisition was an attempt to subject a portion of the items covered by IPB No. 80 to another bidding; and praying that a TRO issue to enjoin respondents' proposed bidding for the wooden poles. 14. Respondents sought the dismissal of the case, stating that the complaint averred no cause of action, violated the rule that government infrastructure projects were not to be subjected to TROs, contravened the mandatory prohibition against non-forum shopping, and the corporate president had no authority to sign and file the complaint. 15. RTC granted a TRO 16. Respondent filed appeal with CA. CA granted petition and annulled and set aside the TRO. ISSUES: I. Whether or not the CA erred in dismissing the case on the basis of Rep. Act 8975 prohibiting the issuance of temporary restraining orders and

preliminary injunctions, except if issued by the Supreme Court, on government projects. HELD: The petition fails. The CA explained why it annulled and set aside the assailed orders of the RTC: It is beyond dispute that the crux of the instant case is the propriety of respondent Judge's issuance of a preliminary injunction, or the earlier TRO, for that matter. Respondent Judge gravely abused his discretion in entertaining an application for TRO/preliminary injunction, and worse, in issuing a preliminary injunction through the assailed order enjoining petitioners' sought bidding for its O-ILAW Project. The same is a palpable violation of RA 8975 which was approved on November 7, 2000, thus, already existing at the time respondent Judge issued the assailed Order. Section 3 of RA 8975 states in no uncertain terms, thus: Prohibition on the Issuance of temporary Restraining Order, Preliminary Injunctions and Preliminary Mandatory Injunctions. No court, except the Supreme Court, shall issue any temporary restraining order, preliminary injunction or preliminary mandatory injunction against the government, or any of its subdivisions, officials, or any person or entity, whether public or private, acting under the government's direction, to restrain, prohibit or compel the following acts: xxx xxx xxx (b) Bidding or awarding of contract/project of the national government as defined under Section 2 hereof; aSCHcA xxx xxx xxx This prohibition shall apply in all cases, disputes or controversies instituted by a private party, including but not limited to cases filed by bidders or those claiming to have rights through such bidders involving such contract/project. This prohibition shall not apply when the matter is of extreme urgency involving a constitutional issue, such that unless a temporary restraining order is issued, grave injustice and irreparable injury will arise. . . . The said proscription is not entirely new. RA 8975 merely supersedes PD 1818 which earlier underscored the prohibition to courts from issuing restraining orders or preliminary injunctions in cases involving infrastructure or National Resources Development projects of, and public utilities operated by, the government. This law was, in fact, earlier upheld to have such a mandatory nature by the Supreme Court in an administrative case against a Judge.

Moreover, to bolster the significance of the said prohibition, the Supreme Court had the same embodied in its Administrative Circular No. 11-2000 which reiterates the ban on issuance of TRO or writs of Preliminary Prohibitory or Mandatory Injunction in cases involving Government Infrastructure Projects. Thus, there is nothing from the law or jurisprudence, or even from the facts of the case, that would justify respondent Judge's blatant disregard of a "simple, comprehensible and unequivocal mandate (of PD 1818) prohibiting the issuance of injunctive writs relative to government infrastructure projects." Respondent Judge did not even endeavor, although expectedly, to show that the instant case falls under the single exception where the said proscription may not apply, i.e., when the matter is of extreme urgency involving a constitutional issue, such that unless a temporary restraining order is issued, grave injustice and irreparable injury will arise. Respondent Judge could not have legally declared petitioner in default because, in the first place, he should not have given due course to private respondent's complaint for injunction. Indubitably, the assailed orders were issued with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction. The CA's decision was absolutely correct. The RTC gravely abused its discretion, firstly, when it entertained the complaint of Nerwin against respondents notwithstanding that Nerwin was thereby contravening the express provisions of Section 3 and Section 4 of Republic Act No. 8975 for its seeking to enjoin the bidding out by respondents of the O-ILAW Project; and, secondly, when it issued the TRO and the writ of preliminary prohibitory injunction. Section 3 and Section 4 of Republic Act No. 8975 provide: Section 3. Prohibition on the Issuance of Temporary Restraining Orders, Preliminary Injunctions and Preliminary Mandatory Injunctions. No court, except the Supreme Court, shall issue any temporary restraining order, preliminary injunction or preliminary mandatory injunction against the government, or any of its subdivisions, officials or any person or entity, whether public or private, acting under the government's direction, to restrain, prohibit or compel the following acts: (a) Acquisition, clearance and development of the right-of-way and/or site or location of any national government project; (b) Bidding or awarding of contract/project of the national government as defined under Section 2 hereof; (c) Commencement, prosecution, execution, implementation, operation of any such contract or project;

(d) Termination or rescission of any such contract/project; and (e) The undertaking or authorization of any other lawful activity necessary for such contract/project. This prohibition shall apply in all cases, disputes or controversies instituted by a private party, including but not limited to cases filed by bidders or those claiming to have rights through such bidders involving such contract/project. This prohibition shall not apply when the matter is of extreme urgency involving a constitutional issue, such that unless a temporary restraining order is issued, grave injustice and irreparable injury will arise. The applicant shall file a bond, in an amount to be fixed by the court, which bond shall accrue in favor of the government if the court should finally decide that the applicant was not entitled to the relief sought. If after due hearing the court finds that the award of the contract is null and void, the court may, if appropriate under the circumstances, award the contract to the qualified and winning bidder or order a rebidding of the same, without prejudice to any liability that the guilty party may incur under existing laws. Section 4. Nullity of Writs and Orders. Any temporary restraining order, preliminary injunction or preliminary mandatory injunction issued in violation of Section 3 hereof is void and of no force and effect. The text and tenor of the provisions being clear and unambiguous, nothing was left for the RTC to do except to enforce them and to exact upon Nerwin obedience to them. The RTC could not have been unaware of the prohibition under Republic Act No. 8975 considering that the Court had itself instructed all judges and justices of the lower courts, through Administrative Circular No. 11-2000, to comply with and respect the prohibition against the issuance of TROs or writs of preliminary prohibitory or mandatory injunction involving contracts and projects of the Government. DM CONSUNJI vs CA and JUEGO Facts: -Jose Juego, a construction worker of DM Consunji, Inc., fell 14 floors from the Renaissance Tower, Pasig City which resulted to his instant death. Jose Juegos widow, Maria, filed in the RTC of Pasig a complaint for damages against the deceaseds employer, D.M. Consunji, Inc. The employer raised, among other defenses, the widows prior availment of the benefits from the State Insurance Fund.

-RTC- rendered a decision in favor of the widow Maria Juego ordering the defendant to pay the plaintiff for the death of Jose, actual, compensatory and moral damages, Joses loss of earning capacity, attorneys fees and the costs of suit. -CA- reversed RTCs decision in toto Issue: Whether or not the injured employee or his heirs in case of death have a right of selection or choice of action between availing themselves of the workers right under the Workmens Compensation Act and suing in the regular courts under the Civil Code for higher damages (actual, moral and exemplary) from the employers by virtue of the negligence or fault of the employers or whether they may avail themselves cumulatively of both actions. Held: As a general rule, the claims for damages sustained by workers in the course of their employment could be filed only under the Workmens Compensation Law, to the exclusion of all further claims under other laws. The Court of Appeals, however, held that the case at bar came under exception because private respondent was unaware of petitioners negligence when she filed her claim for death benefits from the State Insurance Fund. Had the claimant been aware, she wouldve opted to avail of a better remedy than that of which she already had. Waiver of rights The choice of a party between inconsistent remedies results in a waiver by election. Hence, the rule in Florescathat a claimant cannot simultaneously pursue recovery under the Labor Code and prosecute an ordinary course of action under the Civil Code. The claimant, by his choice of one remedy, is deemed to have waived the other. Waiver is the intentional relinquishment of a known right. It is an act of understanding that presupposes that a party has knowledge of its rights, but chooses not to assert them. It must be generally shown by the party claiming a waiver that the person against whom the waiver is asserted had at the time knowledge, actual or constructive, of the existence of the partys rights or of all material facts upon which they depended. Where one lacks knowledge of a right, there is no basis upon which waiver of it can rest. Ignorance of a material fact negates waiver, and waiver cannot be established by a consent given under a mistake or misapprehension of fact.

A person makes a knowing and intelligent waiver when that person knows that a right exists and has adequate knowledge upon which to make an intelligent decision. Waiver requires a knowledge of the facts basic to the exercise of the right waived, with an awareness of its consequences. That a waiver is made knowingly and intelligently must be illustrated on the record or by the evidence. That lack of knowledge of a fact that nullifies the election of a remedy is the basis for the exception in Floresca. Waiver is a defense, and it was not incumbent upon private respondent, as plaintiff, to allege in her complaint that she had availed of benefits from the ECC. It is, thus, erroneous for petitioner to burden private respondent with raising waiver as an issue. On the contrary, it is the defendant who ought to plead waiver, as petitioner did in pages 2-3 of its Answer; otherwise, the defense is waived. It is, therefore, perplexing for petitioner to now contend that the trial court had no jurisdiction over the issue when petitioner itself pleaded waiver in the proceedings before the trial court. There is no showing that private respondent knew of the remedies available to her when the claim before the ECC was filed. On the contrary, private respondent testified that she was not aware of her rights. Ignorance of the Law Petitioner, though, argues that under Article 3 of the Civil Code, ignorance of the law excuses no one from compliance therewith. As judicial decisions applying or interpreting the laws or the Constitution form part of the Philippine legal system (Article 8, Civil Code), private respondent cannot claim ignorance of this Courts ruling inFloresca allowing a choice of remedies. The argument has no merit. The application of Article 3 is limited to mandatory and prohibitory laws. This may be deduced from the language of the provision, which, notwithstanding a persons ignorance, does not excuse his or her compliance with the laws. The rule in Floresca allowing private respondent a choice of remedies is neither mandatory nor prohibitory. Accordingly, her ignorance thereof cannot be held against her. AUJERO vs PHILCOMSAT

Petitioner Hypte Aujero was the Vice President of respondent company Philippine Communications Satellite Corporation (Philcomsat). After 34 years, he applied for an early retirement which was approved. This entitled Aujero to receive his retirement benefits at a rate equivalent to one and a half of his monthly salary for every year of service. Aujero subsequently executed a Deed of Release and Quitclaim in Philcomsats favor following his receipt from the latter of a check in the amount of P9,439,327.91. After 3 years, Aujero filed a complaint for unpaid retirement benefits claiming that the actual amount of his retirement pay is P14,015,055.00. Aujero contends that the significantly deficient amount he previously received was more than an enough reason to declare his quitclaim null and void. Aujero further claimed that he had no choice but to accept the lesser amount as he was in dire need of money. The Labor Arbiter (LA) ruled in favor of Aujero and directed Philcomsat to pay the balance of his retirement pay. The LA maintained that Philcomsat failed to substantiate its claim that the amount received by Aujero was a product of negotiations between the parties. On appeal, the National Labor Relations Commissions (NLRC) reversed the decision of the LA and decided in favor of Philcomsat. The Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the NLRC. W/N the quitclaim executed by the petitioner in Philcomsats favor is valid, thereby foreclosing his right to institute any claim against Philcomsat? SC = YES. While the law looks with disfavor upon releases and quitclaims by employees who are inveigled or pressured into signing them by unscrupulous employers seeking to evade their legal responsibilities, a legitimate waiver representing a voluntary settlement of a laborer's claims should be respected by the courts as the law between the parties. Considering Aujeros claim of fraud and bad faith against Philcomsat to be unsubstantiated, the Court finds the quitclaim in dispute to be legitimate waiver. That Aujero was all set to return to his hometown and was in dire need of money would likewise not qualify as undue pressure sufficient to invalidate the quitclaim. Dire necessity may be an acceptable ground to annul quitclaims if the consideration is unconscionably low and the employee was tricked into accepting it, but is not an acceptable ground for annulling the release when it is not shown that the employee has been forced to execute it. While it is the Courts duty to prevent the exploitation of employees, it also behooves this Court to protect the sanctity of contracts that do not contravene our laws.

Aujeros educational background and employment stature render it improbable that he was pressured, intimidated or inveigled into signing the subject quitclaim. The Court cannot permit the petitioner to relieve himself from the consequences of his act, when his knowledge and understanding thereof is expected. Also, the period of time that Aujero allowed to lapse before filing a complaint to recover the supposed deficiency in his retirement pay clouds his motives, leading to the reasonable conclusion that his claim of being aggrieved is a mere afterthought, if not a mere pretention. Absent any evidence that any of the vices of consent is present, the quitclaim executed by a party constitutes a valid and binding agreement. VILLAREAL vs PEOPLE FF CRUZ vs HR INDUSTRIES F.F. Cruz & Co., Inc. (FFCCI) entered into a contract with the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) for the construction of the Magsaysay Viaduct. FFCCI, in turn, entered into a Subcontract Agreement with HR Construction Corporation (HRCC) for the supply of materials, labor, equipment, tools and supervision for the construction of a portion of the said project. Pursuant to the Subcontract Agreement, HRCC would submit to FFCCI a monthly progress billing which the latter would then pay, subject to stipulated deductions, within 30 days from receipt thereof. The parties agreed that the requests of HRCC for payment should include progress accomplishment of its completed works as approved by FFCCI. Additionally, they agreed to conduct a joint measurement of the completed works of HRCC together with the representative of DPWH and consultants to arrive at a common quantity. HRCC submitted to FFCCI its first progress billing covering the construction works it completed from August 16 to September 15, 2004. However, FFCCI asserted that the DPWH was then able to evaluate the completed works of HRCC only until July 25, 2004. Thus, FFCCI only approved the gross amount assessed by the DPWH during said period, which was far less than that billed by HRCC. FFCCI and the DPWH then jointly evaluated the completed works of HRCC for the period of July 26 to September 25, 2004 as the approved net payment for the said period. FFCCI paid this amount HRCC submitted to FFCCI its second progress billing covering its completed works from September 18 to 25, 2004. FFCCI did not pay the amount stated in the second progress billing, claiming that it had

already paid HRCC for the completed works for the period stated therein. HRCC submitted its third progress billing for its completed works from September 26 to October 25, 2004. FFCCI did not immediately pay the amount stated in the third progress billing, claiming that it still had to evaluate the works accomplished by HRCC. HRCC submitted to FFCCI its fourth progress billing for the works it had completed from October 26 to November 25, 2004. Subsequently, FFCCI, after it had evaluated the completed works approved the payment of a gross amount far less from what HRCC billed (around 6 Million worth of difference) which amount was paid to HRCC. Meanwhile, HRCC sent FFCCI a letter demanding the payment of its progress billings within three days from receipt thereof. Subsequently, HRCC completely halted the construction of the subcontracted project. HRCC, pursuant to an arbitration clause in the Subcontract Agreement, filed with the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC) a Complaint against FFCCI praying for the payment of the overdue obligation and attorney's fees. FFCCI claimed that it no longer has any liability on the Subcontract Agreement as the three payments it made to HRCC already represented the amount due to the latter in view of the works actually completed by HRCC as shown by the survey it conducted jointly with the DPWH. Likewise, FFCCI maintained that HRCC failed to comply with the condition stated under the Subcontract Agreement for the payment of the latter's progress billings, i.e., joint measurement of the completed works, and, hence, it was justified in not paying the amount stated in HRCC's progress billings. The CIAC rendered a Decision in favor of HRCC, holding that the payment method adopted by FFCCI is actually what is known as the "back-to-back payment scheme" which was not agreed upon under the Subcontract Agreement. As such, the CIAC ruled that FFCCI could not impose upon HRCC its valuation of the works completed by the latter. FFCCI then filed a petition for review with CA assailing the foregoing disposition by the CIAC. On appeal, the CA rendered a Decision denying the petition for review filed by FFCCI. FFCCI sought for reconsideration but it was denied. ISSUES: 1.) Whether FFCCI's non-compliance with the stipulation in the Subcontract Agreement requiring a joint quantification of the works

completed by HRCC on the payment of the progress billings submitted by the latter constitutes as a waiver of its right to question HRCCs billings? 2.) Whether there was a valid rescission of the Subcontract Agreement by HRCC? HELD: 1.) YES 2.) NO Decision and Resolution of the Court of Appeals are hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION that the arbitration costs shall be shared equally by the parties herein. RATIO: 1.) First Issue: Effect of Non-compliance with the Joint Quantification Requirement on the Progress Billings of HRCC (IMPLIED WAIVER) The petition by FFCCI is not meritorious. The main question advanced by FFCCI is this: in the absence of the joint measurement agreed upon in the Subcontract Agreement, how will the completed works of HRCC be verified and the amount due thereon be computed? The determination of the foregoing question entails an interpretation of the terms of the Subcontract Agreement vis--vis the respective rights of the parties herein. Basically, the instant issue calls for a determination as to which of the parties' respective valuation of accomplished works should be given credence. The terms of the Subcontract Agreement should prevail. It is the responsibility of FFCCI to call for the joint measurement of HRCC's completed works. The joint measurement contemplated under the Subcontract Agreement should be conducted by the parties herein together with the representative of the DPWH and the consultants. FFCCI, on account of its failure to demand the joint measurement of HRCC's completed works, had effectively waived its right to ask for the conduct of the same as a condition sine qua non to HRCC's submission of its monthly progress billings. In People of the Philippines v. Donato Waiver is defined as "a voluntary and intentional relinquishment or abandonment of a known existing legal right, advantage, benefit, claim or privilege, which except for such waiver the party would have enjoyed; the voluntary abandonment or surrender, by a capable person, of a right known by him to exist, with the intent that such right shall be surrendered and such person forever deprived of its benefit; or such conduct as warrants an inference of the

relinquishment of such right; or the intentional doing of an act inconsistent with claiming it." As to what rights and privileges may be waived, the authority is settled: . . . the doctrine of waiver extends to rights and privileges of any character, and, since the word 'waiver' covers every conceivable right, it is the general rule that a person may waive any matter which affects his property, and any alienable right or privilege of which he is the owner or which belongs to him or to which he is legally entitled, whether secured by contract, conferred with statute, or guaranteed by constitution, provided such rights and privileges rest in the individual, are intended for his sole benefit, do not infringe on the rights of others, and further provided the waiver of the right or privilege is not forbidden by law, and does not contravene public policy; and the principle is recognized that everyone has a right to waive, and agree to waive, the advantage of a law or rule made solely for the benefit and protection of the individual in his private capacity, if it can be dispensed with and relinquished without infringing on any public right, and without detriment to the community at large. . . . Here, it is undisputed that the joint measurement of HRCC's completed works contemplated by the parties in the Subcontract Agreement never materialized. FFCCI did not contest the said progress billings submitted by HRCC despite the lack of a joint measurement of the latter's completed works as required under the Subcontract Agreement. Instead, FFCCI proceeded to conduct its own verification of the works actually completed by HRCC and, on separate dates, made the said payments to HRCC. FFCCI's voluntary payment in favor of HRCC, albeit in amounts substantially different from those claimed by the latter, is a glaring indication that it had effectively waived its right to demand for the joint measurement of the completed works. FFCCI's failure to demand a joint measurement of HRCC's completed works reasonably justified the inference that it had already relinquished its right to do so. FFCCI is already barred from contesting HRCC's valuation of the completed works having waived its right to demand the joint measurement requirement. The joint measurement requirement is a mechanism essentially granting FFCCI the opportunity to verify and, if necessary, contest HRCC's valuation of its completed works prior to the submission of the latter's monthly progress billings. Thus, having relinquished its right to ask for a joint measurement of HRCC's completed works, FFCCI had necessarily waived its right to dispute HRCC's valuation of the works it had accomplished.

2.) Second Issue: Validity of HRCC's Rescission of the Subcontract Agreement (EXPRESS WAIVER) The determination of the validity of HRCC's work stoppage depends on a determination of the following: first, whether HRCC has the right to extrajudicially rescind the Subcontract Agreement; and second, whether FFCCI is already barred from disputing the work stoppage of HRCC. HRCC had waived its right to rescind the Subcontract Agreement. The right of rescission is statutorily recognized in reciprocal obligations as stated in Article 1191 of the Civil Code. However, while the right to rescind reciprocal obligations is implied, that is, that such right need not be expressly provided in the contract, nevertheless the contracting parties may waive the same. HRCC had no right to rescind the Subcontract Agreement in the guise of a work stoppage, the latter having waived such right, the Subcontract Agreement reads: Notwithstanding any dispute, controversy, differences or arbitration proceedings relating directly or indirectly to this SUBCONTRACT Agreement and without prejudice to the eventual outcome thereof, HRCC shall at all times proceed with the prompt performance of the Works in accordance with the directives of FFCCI and this SUBCONTRACT Agreement. In spite of the existence of dispute or controversy between the parties during the course of the Subcontract Agreement, HRCC had agreed to continue the performance of its obligations pursuant to the Subcontract Agreement. The costs of arbitration should, therefore, be shared by the parties equally, applying Section 1, Rule 142 of the Rules of Court. THORNTON vs THORNTON PR (R:45) CAs resolution which dismissed the petition for habeas corpus on the grounds of lack of jurisdiction and lack of substance. FACTS: Petitioner (American) and respondent were married on August 28, 1998. A year later, respondent gave birth to a baby girl, Sequeira Jennifer Delle Francisco Thornton. After 3 years, respondent grew restless and bored as a plain housewife. She wanted to return to her old job as a guest relations officer in a nightclub. Whenever the petitioner was out of

the country, respondent was often out with her friends, leaving her daughter in the care of the househelp. Petitioner admonished respondent about her irresponsibility but she continued her carefree ways. On December 7, 2001, respondent left the family home with her daughter without notifying her husband. She told the servants that she was bringing Sequiera to Lamitan, Basilan Province. Petitioner filed a petition for habeas corpus in the designated Family Court in Makati City but this was dismissed because of the allegation that the child was in Basilan. Petitioner went to Basilan, but did not find them there and the barangay office issued a certification that respondent was no longer residing there. Petitioner gave up his search when he got hold of respondents cellular phone bills showing calls from different places such as Cavite, Nueva Ecija, Metro Manila and other provinces. Petitioner then filed another petition for habeas corpus with the Court of Appeals which could issue a writ of habeas corpus enforceable in the entire country. However, CA denied the petition on the ground that it did not have jurisdiction over the case. It ruled that since RA 8369 (The Family Courts Act of 1997) gave family courts exclusive original jurisdiction over petitions for habeas corpus, it impliedly repealed RA 7902 (An Act Expanding the Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals) and Batas Pambansa 129 (The Judiciary Reorganization Act of 1980). In 1997, RA 8369 otherwise known as Family Courts Act was enacted. 5(b) provides that Family Courts have exclusive original jurisdiction to hear and decide petition cases for guardianship, custody of children, habeas corpus in relation to the latter.

ISSUE: Whether or not RA 8369 impliedly repealed RA 7902 and BP 129, divesting the Court of Appeals to issue writs of habeas corpus in cases involving custody of minors? RULING: The petition is granted. CA should take cognizance of the case since there is nothing in RA 8369 that revoked its jurisdiction to issue writs of habeas corpus involving the custody of minors. SGs COMMENT: