Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Nevada Reports 1972 (88 Nev.) PDF

Hochgeladen von

thadzigsOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Nevada Reports 1972 (88 Nev.) PDF

Hochgeladen von

thadzigsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

88 Nev.

1, 1 (1972)

REPORTS OF CASES

DETERMINED BY THE

SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF NEVADA

____________

Volume 88

____________

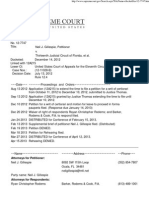

88 Nev. 1, 1 (1972) Memory Gardens v. Pet Ponderosa

MEMORY GARDENS OF LAS VEGAS, INC., a Nevada Corporation, Appellant, v. PET

PONDEROSA MEMORIAL GARDENS, INC., a Nevada Corporation, Respondent.

No. 6461

January 3, 1972 492 P.2d 123

Appeal from an order granting a preliminary injunction by the Eighth Judicial District

Court, Clark County; Clarence Sundean, Judge.

After defendant terminated water supply to plaintiff's pet cemetery, plaintiff commenced

lawsuit for injunctive relief and damages. The district court granted preliminary injunction,

and appeal was taken. The Supreme Court, Batjer, J., held that in light of status quo to be

maintained of growing lawn, plants and trees which could only be accomplished by restoring

water to the land and showing of irreparable injury in rendering pet cemetery barren and

devoid of grass and shrubbery and in keeping it in that condition and very definite possibility

of multiple lawsuits against plaintiff, granting preliminary injunction was proper.

Affirmed.

88 Nev. 1, 2 (1972) Memory Gardens v. Pet Ponderosa

Wiener, Goldwater & Galatz and Herbert L. Waldman, of Las Vegas, for Appellant.

John Peter Lee, of Las Vegas, for Respondent.

1. Injunction.

Where defendant leased to plaintiff approximately ten acres of land to be used as pet cemetery and by

agreement allowed plaintiff to use all available water for two hours each evening in order to develop and

maintain landscaping at pet cemetery but subsequently defendant summarily terminated water supply,

status quo was growing lawn, plants and trees which could only have been accomplished by restoring water

to the land and granting of preliminary injunction against defendant would not be improper on ground that

drying up of grass and shrubbery had been accomplished and there remained no status quo to be

maintained.

2. Injunction.

Even if act causing injury has been completed before action is instituted, a mandatory injunction may be

granted to restore the status quo.

3. Injunction.

Where defendant leased to plaintiff approximately ten acres of land to be used as pet cemetery and agreed

that plaintiff be allowed to use all available water for two hours each evening but summarily thereafter

terminated water supply to plaintiff's property, rendering pet cemetery barren and devoid of grass and

shrubbery and keeping it in that condition was an irreparable physical change and there was a very definite

possibility of multiple lawsuits against plaintiff if pet cemetery continued in barren condition and plaintiffs

showed sufficient irreparable injury so as to support preliminary injunction against defendant.

4. Injunction.

Any act which destroys or results in substantial change in property, either physically or in character in

which it has been held or enjoyed, does irreparable injury which justifies injunctive relief.

5. Injunction.

Where there was nothing in record to show any prejudice to defendant, five-month delay between

termination of water supply to plaintiff under agreement between plaintiff and defendant and filing of

action by plaintiff did not amount to laches.

6. Equity.

Alleged prejudice so that a delay will amount to laches cannot be prospective or illusory.

OPINION

By the Court, Batjer, J.:

On September 2, 1967, the appellant leased to the respondent approximately ten acres of

land to be used as a pet cemetery. This land adjoined the appellant's human cemetery. By

agreement, the appellant allowed the respondent to use all available water for two hours

each evening in order to develop and maintain the landscaping at the pet cemetery.

88 Nev. 1, 3 (1972) Memory Gardens v. Pet Ponderosa

agreement, the appellant allowed the respondent to use all available water for two hours each

evening in order to develop and maintain the landscaping at the pet cemetery.

The record indicates that over 300 pets were buried in the cemetery at the time this action

arose, and each individual who buried a pet paid an initial interment fee plus a fee of $2.50

per year for a period of up to ninety years to finance the maintenance of the property.

On February 1, 1970, the appellant summarily terminated the water supply to the

respondent's property. Within a short period of time the grass, shrubs and trees dried up and

died.

After the water supply had been cut off, the president of the respondent corporation

attempted to renegotiate the lease agreement with the appellant, but to no avail. Attempts

were also made to obtain the services of a water truck to haul water to the pet cemetery but

that proved too expensive. The respondent contacted other water users in the area in an effort

to purchase water from them but they were not able to spare any water from their wells.

On June 7, 1970, more than four months after the water supply had been terminated, the

respondent commenced this lawsuit seeking injunctive relief and damages. After a hearing on

the matter, the trial court entered its findings of fact and conclusions of law and granted a

preliminary injunction requiring the appellant to allow the respondent the use of the entire

water supply available at its cemetery for a period two hours each evening, seven days a

week. The trial court indicated that the preliminary injunction was granted because there was

no readily available source of water and no well could be drilled by the respondent without

the consent of the appellant. It also found that the condition of the pet cemetery was such at

the time of the hearing that many owners of pets interred therein could sue to enforce their

contract rights requiring upkeep of the property, and that such suits were inestimable and

could run into hundreds in number.

The appellant contends that the trial court erred in granting the preliminary injunction

because the drying up of the grass and shrubbery had been accomplished and there remained

no status quo to be maintained, and that the respondent had failed to show, at the time of the

hearing, any irreparable injury.

[Headnote 1]

Relying upon Sherman v. Clark, 4 Nev. 138 (1868) and Berryman v. Int'l. Bhd. Elec.

Workers, 82 Nev. 277, 416 P.2d 387 (1966), the appellant contends that inasmuch as the

grass and shrubbery were dead at the time of the hearing on the motion for a preliminary

injunction, the wrong, if any, had been completed, and if an injury has been completed a

mandatory injunction can have no effect for it cannot be applied correctively so as to

remove the wrong.

88 Nev. 1, 4 (1972) Memory Gardens v. Pet Ponderosa

motion for a preliminary injunction, the wrong, if any, had been completed, and if an injury

has been completed a mandatory injunction can have no effect for it cannot be applied

correctively so as to remove the wrong. The law enunciated in those cases is inapposite for

here the injury was continuing because neither grass nor shrubbery will grow as long as water

is withheld. Furthermore, the respondent would have been subject to a multiplicity of lawsuits

by the owners of pets buried in its cemetery as long as the drought continued.

[Headnote 2]

Status quo in this case was the growing lawn, plants and trees and that could only have

been accomplished by restoring the water to the land. Unless the water was restored to the

land it would lie barren and the injury to the respondent and its lessees would continue. Even

if the act causing the injury has been completed before the action is instituted, a mandatory

injunction may be granted to restore the status quo. City of Reno v. Matley, 79 Nev. 49, 378

P.2d 256 (1963). Injunctions of this type have frequently been employed in cases involving

irrigation and water rights. Grosfield v. Johnson, 39 P.2d 660 (Mont. 1935). See also Sokel v.

Nickoli, 79 N.W.2d 485 (Mich. 1956) (garage had already been built when suit instituted);

Van De Carr v. Schloss, 101 N.Y.S.2d 48 (App. Div. 1950) (erection of boathouse); Harris v.

Pierce, 73 So.2d 330 (La.Ct.App. 1954) (erection of building); Texas Co. v. Watkins, 82

S.W.2d 1079 (Tex.Ct.Civ.App. 1935); Baltimore & P.S. Co. v. Ministers, Etc., Starr

M.P.Church, 130 A. 46 (Md.Ct.App. 1925).

[Headnote 3]

The appellant's contention that the respondent failed to show irreparable injury is also

without merit. Here the trial court found the irreparable injury to be the unavailability of other

sources of water, a continuing barren landscape, and the possibility of multitudinous

litigation.

[Headnote 4]

Any act which destroys or results in a substantial change in property, either physically or

in the character in which it has been held or enjoyed, does irreparable injury which justifies

injunctive relief. See Lackaff v. Bogue, 62 N.W.2d 889 (Neb. 1954); Viestenz v. Arthur Tp.,

54 N.W.2d 572 (N.D. 1952); Armbruster v. Stanton-Pilger Drainage District, 100 N.W.2d

781 (Neb. 1960); Faught v. Platte Valley Public Power & Irr. Dist., 25 N.W.2d 889 (Neb.

1947); Hood v. Foster, 13 So.2d 652 {Miss.

88 Nev. 1, 5 (1972) Memory Gardens v. Pet Ponderosa

So.2d 652 (Miss. 1943); and Roseberg v. American Hotel & Garden Co., 121 A. 9 (N.J.Ch.

1923). Rendering the pet cemetery barren and devoid of grass and shrubbery and keeping it in

that condition was an irreparable physical change.

The avoidance of multiple lawsuits is also a justifiable basis for a mandatory injunction.

See Home Finance Co. v. Balcom, 61 Nev. 301, 127 P.2d 389 (1942). Here there was a very

definite possibility of multiple lawsuits against the respondent if the pet cemetery continued

in a barren condition.

[Headnotes 5, 6]

The appellant also claims that the respondent was guilty of laches because of the

five-month delay between termination of the water supply and filing of the action. Such a

delay not causing actual prejudice does not amount to laches. The alleged prejudice cannot be

prospective or illusory. Rheinberger v. Security Life Ins. Co. of America, 51 F.Supp. 188

(N.D.Ill. 1943); McCavic v. DeLuca, 46 N.W.2d 873 (Minn. 1951); Sullivan v. Balestrieri,

298 P.2d 688 (Cal.App. 1956); and Scioscia v. Iovieno, 63 N.E.2d 898 (Mass. 1945). There is

nothing in this record to show any prejudice whatsoever to the appellant, nor do we find any

specific allegation of prejudice by the appellant. As a matter of fact, it appears that the delay

was to appellant's benefit for during that period of time it had an extra volume of water to use

on its cemetery.

The order of the district court is affirmed.

Zenoff, C. J., and Mowbray, Thompson, and Gunderson, JJ., concur.

____________

88 Nev. 5, 5 (1972) Savini Constr. v. A & K Earthmovers

SAVINI CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, a Co-Partnership, Appellant, v. A & K

EARTHMOVERS, INC., a Nevada Corporation, Respondent.

No. 6572

January 3, 1972 492 P.2d 125

Appeal from a judgment of the First Judicial District Court, Churchill County; Richard L.

Waters, Jr., Judge.

Action by prime contractor for state highway construction project against subcontractor for

breach of contract. The district court entered judgment for defendant, and plaintiff appealed.

The Supreme Court held that evidence supported finding that defendant had fully

performed pursuant to oral subcontract, and that substantial evidence test is particularly

applicable where there is conflicting evidence and credibility of witnesses is in issue.

88 Nev. 5, 6 (1972) Savini Constr. v. A & K Earthmovers

finding that defendant had fully performed pursuant to oral subcontract, and that substantial

evidence test is particularly applicable where there is conflicting evidence and credibility of

witnesses is in issue.

Affirmed.

Seymour H. Patt, of Reno, for Appellant.

Diehl, Recanzone, Evans & Smart, of Fallon, for Respondent.

1. Contracts.

Evidence, in action by prime contractor for state highway construction project against subcontractor for

breach of contract, supported finding that subcontractor had fully performed pursuant to oral subcontract

for moving earth from cut in proposed roadway to fills at bridge abutment.

2. Appeal and Error.

Substantial evidence test is particularly applicable where there is conflicting evidence and credibility of

witnesses is in issue.

3. Witnesses.

In absence of showing that resident state engineer had any personal knowledge of provisions of oral

subcontract, any testimony by him regarding terms of subcontract would have been conjecture and

therefore not admissible in action by prime contractor for state highway construction project against

subcontractor for breach of contract.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

The appellant was the prime contractor on the Pinion Hills Bridge, a state highway

construction project. The respondent submitted a bid offer of 35 cents a yard for moving

certain earth on the project from a cut in the proposed roadway to fills at the bridge abutments

and was awarded a subcontract at that price by the appellant. No written contract was ever

executed, but the parties orally agreed concerning the work to be performed under the

subcontract. On November 13, 1969, the respondent left the job claiming that the earth fills at

the bridge abutments had been completed and the contract had been fully performed. The

appellant claims that the roadway excavation had not been completed by the respondent

according to the master contract or the subcontract, and that it was required to do additional

excavation work to complete the project.

Thereafter the appellant filed a complaint against the respondent to recover $3,146.41 that

it alleged it had been required to spend to complete the excavation work left unfinished by

the respondent.

88 Nev. 5, 7 (1972) Savini Constr. v. A & K Earthmovers

required to spend to complete the excavation work left unfinished by the respondent. After a

trial on the merits, the district court found that the appellant was not entitled to recover on its

complaint because the respondent had fully performed pursuant to the oral subcontract. In this

appeal the appellant contends that there was insufficient evidence to support that finding.

[Headnotes 1, 2]

We have reviewed the record and find substantial evidence to support the trial court's

judgment. Kenneth Hiatt, general manager for the respondent, testified that all of the roadway

excavation agreed to under the subcontract had been completed by the respondent at the time

it left the project. The trial judge chose to believe Hiatt's testimony. There is no showing by

the appellant that the judgment of the trial court was clearly erroneous or was not based upon

substantial evidence. Brandon v. Travitsky, 86 Nev. 613, 472 P.2d 353 (1970); Utley v.

Airoso, 86 Nev. 116, 464 P.2d 778 (1970). The substantial evidence test is particularly

applicable here where there is conflicting evidence and the credibility of the witnesses is in

issue. Douglas Spencer v. Las Vegas Sun, 84 Nev. 279, 439 P.2d 473 (1968); Briggs v.

Zamalloa, 83 Nev. 400, 432 P.2d 672 (1967).

[Headnote 3]

It is also asserted by the appellant that the trial court erred in refusing to allow the

testimony of the resident state engineer regarding the provisions of the subcontract. After a

timely objection, the trial court correctly ruled that inasmuch as there had been no showing

that the witness had any personal knowledge of the provisions of the subcontract, any

testimony by him would be merely conjecture and therefore inadmissible. See Deakyne v.

Lewes Anglers, Inc., 204 F.Supp. 415 (D.Del. 1962).

Affirmed.

____________

88 Nev. 7, 7 (1972) Johnston, Inc. v. Weinstein

JOHNSTON, INC. a Texas Corporation, Appellant, v. JACK WEINSTEIN and SANDRA

BANKSTON, dba PLAYMATES BY SAUNDRA, INC., Respondents.

No. 6559

January 11, 1972 492 P.2d 616

Appeal from order setting aside default judgment. Eighth Judicial District Court; William

R. Morse, Judge.

88 Nev. 7, 8 (1972) Johnston, Inc. v. Weinstein

Action for money due from sale of merchandise and for punitive damages as result of

allegedly fraudulent representations. The Supreme Court held that where defendants' motion

to set aside default judgment, and affidavit and supporting document attached thereto,

containing factual assertions to show excusable neglect and what would be a meritorious

defense if proven, in that their business had been sold prior to time plaintiff's suit was filed,

supported defendants' assertions that debt was not theirs, setting aside default judgment was

not an abuse of discretion.

Affirmed.

[Rehearing denied February 23, 1972]

Emilie N. Wanderer, of Las Vegas, for Appellant.

James L. Buchanan II, of Las Vegas, for Respondents.

1. Appeal and Error.

On appeal from order setting aside default judgment, issue is whether setting aside default was an abuse

of discretion, and in absence of clear showing of abuse, action in setting aside default will be affirmed.

2. Judgment.

Where defendants' motion to set aside default judgment, and affidavit and supporting document attached

thereto, containing factual assertions to show excusable neglect and what would be a meritorious defense if

proven, in that their business had been sold prior to time plaintiff's suit for money due from sale of

merchandise was filed, supported defendants' assertions that debt was not theirs, setting aside default

judgment was not an abuse of discretion.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

The appellant filed suit against the respondents for money due from the sale of

merchandise, and for punitive damages as a result of allegedly fraudulent representations.

After service of process upon the respondents and their failure to timely answer the appellant

took a default, and judgment was entered against the respondents on July 29, 1970.

On November 20, 1970, the respondents moved to set aside the judgment. Attached to

their motion was an affidavit containing factual assertions to show excusable neglect and

what would be a meritorious defense if proven. Also attached to the motion was a document

showing that the business of the respondents had been sold prior to the time the appellant's

suit was filed, in support of the assertions of the respondents that the debt was not

theirs.

88 Nev. 7, 9 (1972) Johnston, Inc. v. Weinstein

suit was filed, in support of the assertions of the respondents that the debt was not theirs.

After the appellant's response in opposition to the motion to set aside judgment was filed,

and the parties were heard, the district court entered its order setting aside the judgment and

giving the respondents a time within which to plead further. It is from that order setting aside

the judgment that this appeal is taken.

[Headnote 1]

The sole appellate issue in these circumstances is whether or not the district court abused

its discretion in setting aside the default judgment. In the absence of a clear showing of abuse,

the action of the court below must be affirmed. Hotel Last Frontier v. Frontier Properties,

Inc., 79 Nev. 150, 380 P.2d 293 (1963); Minton v. Roliff, 86 Nev. 478, 471 P.2d 209 (1970).

[Headnote 2]

Upon review of the record on appeal we find that the motion of the respondents to set

aside the default judgment, and the affidavit and supporting document attached thereto, set

forth sufficient facts upon which the district judge could rule that excusable neglect had been

shown, and that they contain allegations which, if proven, would tend to establish a defense to

all or part of the asserted claim for relief. Thus we cannot find such a clear showing of abuse

of discretion as to warrant a reversal of the order setting aside the judgment. Howe v.

Coldren, 4 Nev. 662 (1868); Morris v. Morris, 86 Nev. 45, 464 P.2d 471 (1970).

Affirmed.

____________

88 Nev. 9, 9 (1972) Collins v. State

VARNER RAY COLLINS, Appellant, v. THE STATE

OF NEVADA, Respondent.

No. 6575

January 12, 1972 492 P.2d 991

Appeal from judgment of conviction of robbery by Eighth Judicial District Court, Clark

County; Clarence Sundean, Judge.

The Supreme Court, Mowbray, J., held, inter alia, that arrest at time when there were two

warrants outstanding for such arrest was lawful, and evidence obtained as result thereof was

admissible, though at the time of his arrest the warrants were not in the possession of the

arresting officers, where such officers knew the existence of the warrants.

88 Nev. 9, 10 (1972) Collins v. State

was admissible, though at the time of his arrest the warrants were not in the possession of the

arresting officers, where such officers knew the existence of the warrants.

Affirmed.

Robert G. Legakes, Public Defender, and John C. Ohrenschall, Deputy Public Defender,

Clark County, for Appellant.

Robert List, Attorney General; Roy A. Woofter, District Attorney, and Charles L. Garner,

Chief Deputy of Appeals, Clark County, for Respondent.

1. Arrest; Criminal Law.

Arrest at time when there were two warrants outstanding for such arrest was lawful, and evidence

obtained as result thereof was admissible, though at the time of the arrest the warrants were not in the

possession of the arresting officers, where such officers knew of the existence of the warrants. NRS

171.122, subd, 1.

2. Criminal Law.

Amendment of information immediately prior to trial, at suggestion of the court, to correct misspelling of

defendant's name was not prejudicial. NRS 173.095.

3. Jury.

Absence of any member of defendant's race on petit jury was not error where there was no systematic

exclusion of members of a race or class.

4. Criminal Law.

Fact that witness testified that she believed defendant was the robber but that she was not sure went to the

weight of her testimony, not to its admissibility.

5. Witnesses.

In robbery prosecution, no abuse of discretion was shown in refusal to permit defendant, after the State

had rested its case, to recall officer for purpose of cross-examining him on method used in lifting

fingerprints.

6. Criminal Law.

There was no error in failure to grant defendant's motion for continuance to obtain legal authorities to

challenge the lawfulness of his arrest.

OPINION

By the Court, Mowbray, J.:

Appellant Varner Ray Collins was tried to a jury and convicted of robbery. He has

appealed from his judgment of conviction, and he has assigned numerous assignments of

error, which we reject as meritless and, therefore, affirm the jury's verdict.

88 Nev. 9, 11 (1972) Collins v. State

1. The Facts.

A lone gunman on July 14, 1969, held up the barmaid, Lou Ella Beavers, in the Huddle

Bar located in Las Vegas. The gunman had a beer, minutes before the robbery. He then

produced his weapon and demanded at gunpoint from Lou Ella the contents of the cash

register, which she promptly handed to him. The robber left the premises. Lou Ella

telephoned the police. The Clark County Sheriff's office responded to the call within minutes.

The Sheriff's office had received an anonymous phone call that a late-model, light green

Cougar automobile was seen in the vicinity of the crime. This information was radioed to

Deputy Sheriff Alfred B. Leavitt while he was en route to the crime scene. When the sheriff's

deputies arrived at the Huddle Bar, Lou Ella gave them a description of the robber. Deputy

Sheriff Robert Roderick, in processing the scene of the crime, lifted latent fingerprints from

the beer bottle and glass used by the robber.

The following day, July 15, the sheriff's deputies went to Collins's residence to arrest him

on two pending felony charges (robbery and unlawful possession of narcotics) that had no

connection with the Huddle Bar robbery. As the deputies approached Collins's residence, they

noted in the driveway a vehicle that matched the description of the car that was reported in

the vicinity of the Huddle Bar at the time of the robbery. Upon confronting Collins, the

deputies also observed that his physical appearance matched Lou Ella's description of the

robber. The deputies then arrested Collins and removed him to the county jail, where he was

fingerprinted. The print from appellant's left index finger matched one of the prints taken by

Deputy Roderick at the scene of the crime. The next day, July 16, the officers, upon their

affidavit, obtained a warrant to search Collins's residence. They did so at once and found a

weapon resembling the one used in the robbery. Collins was thereupon charged by criminal

complaint with robbery and later, upon trial, was found guilty thereof.

2. The Arrest and the Search.

A. The Arrest.

[Headnote 1]

First, Collins claims that his arrest was unlawful. His contention is untenable. At the time

he was taken into custody, there were two outstanding warrants for Collins's arrest. It is true

that at the time of the arrest the warrants were not in the deputies' possession, but the deputies

knew of the existence of the warrants.

1

NRS 171.122, subsection 1, is controlling and

dispositive of the arrest issue in this case.

____________________

1

Collins has not attacked the validity of either warrant.

88 Nev. 9, 12 (1972) Collins v. State

NRS 171.122, subsection 1, is controlling and dispositive of the arrest issue in this case. It

provides:

The warrant shall be executed by the arrest of the defendant. The officer need not have

the warrant in his possession at the time of the arrest, but upon request he shall show the

warrant to the defendant as soon as possible. If the officer does not have a warrant in his

possession at the time of the arrest, he shall then inform the defendant of his intention to

arrest him, of the offense charged, the authority to make it and of the fact that a warrant has or

has not been issued. The defendant must not be subjected to any more restraint than is

necessary for his arrest and detention, but if the defendant either flees or forcibly resists, the

officer may use all necessary means to effect the arrest.

B. The Search.

The deputies, in an effort to find the weapon used in the robbery, searched Collins's

residence after his arrest. They first obtained a warrant to do so, based on their affidavit that

Collins's fingerprint matched one found at the scene of the crime. They found a weapon

similar to the one used in the robbery, and it was introduced as evidence during the trial.

Collins challenges the constitutionality of the use of the weapon as evidence, on the ground

that the search was unlawful because his arrest that led to the taking of his fingerprints was

unlawful. Since we have ruled otherwise, i.e., that his arrest was lawful, Collins's contention

on this issue must fail. The weapon was properly received in evidence.

3. The Amendment of the Information.

[Headnote 2]

Immediately prior to trial, the learned trial judge noticed that Collins's name was

misspelled in the information.

2

The judge suggested that the error be corrected on motion by

the district attorney's office. This was done, and Collins claims that it resulted to his

prejudice. NRS 173.095 provides:

The court may permit an information to be amended at any time before verdict or finding

if no additional or different offense is charged and if substantial rights of the defendant are

not prejudiced.

There was no prejudice at all to Collins in this case, and we find this assignment of error

without merit. See Harris v. State, 86 Nev. 197, 466 P.2d 850 (1970).

____________________

2

The trial judge knew Collins and his true name.

88 Nev. 9, 13 (1972) Collins v. State

4. The Composition of the Jury.

[Headnote 3]

Collins next complains that there was no member of his race on the jury that convicted

him and therefore his conviction must be overturned. This may happen in a case. The absence

of members of one's race on a petit jury may occur. If so, it is not error. It is the systematic

exclusion of members of a race or class that spoils the makeup of the jury. Since the record is

void of any such exclusion in this case, the error complained of is meritless. Swain v.

Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, 203-204 (1965); Martin v. Texas, 200 U.S. 316, 320-321 (1906).

5. Lou Ella's Testimony.

[Headnote 4]

Collins complains that, since Lou Ella could not positively identify him as the robber, the

trial judge should have excluded her testimony. Lou Ella testified that she believed Collins

was the robber but that she was not sure. Such an objection goes to the weight of the

testimony, but not to its admissibility. As the court said in People v. Houser, 193 P.2d 937,

941 (Cal. App. 1948):

In order to sustain a conviction it is not necessary that the identification of the defendant

as the perpetrator of the crime be made positively or in a manner free from inconsistencies. It

is the function of the jury to pass upon the strength or weakness of the identification and the

uncertainness of the witness in giving her testimony. [Citation omitted.] See also State v.

Brown, 456 P.2d 368, 370 (Ariz. 1969).

Lou Ella's testimony was properly received and presented to the jury.

6. The Recall of Deputy Roderick.

[Headnote 5]

After the State had rested its case, counsel for Collins sought to recall Deputy Roderick to

the stand for the purpose of cross-examining him on the method he used in lifting the

fingerprints from the beer bottle and glass. Counsel was not permitted to do so, and he asserts

that the trial judge committed reversible error in denying his request. We do not agree. As this

court recently ruled in Casey v. State, 87 Nev. 413, 416, 488 P.2d 546, 548 (1971).

. . . An accused may be permitted to recall a witness for cross-examination after the state

has closed its case. . . . It is, however, for the discretion of the court to disallow such

recross-examination when the party seeking it has had abundant opportunity to draw out

his case.' 3 Wharton's Crim. Ev., 900 {l2th Ed.

88 Nev. 9, 14 (1972) Collins v. State

recross-examination when the party seeking it has had abundant opportunity to draw out his

case.' 3 Wharton's Crim. Ev., 900 (l2th Ed. 1955). On the record in this case, we could not

find that the lower court abused its discretion, even had it refused any additional

cross-examination whatever.

[Headnote 6]

The remaining assignments of error, namely, that the court failed to grant Collins's motion

for a continuance to obtain legal authorities to challenge the lawfulness of his arrest and that

the trial judge denied him a fair trial, are equally unfounded.

The judgment of conviction is affirmed.

Zenoff, C. J., and Batjer, Thompson, and Gunderson, JJ., concur.

____________

88 Nev. 14, 14 (1972) Downey v. Sheriff

JOAN ANN DOWNEY, Appellant, v. SHERIFF,

CLARK COUNTY, NEVADA, Respondent.

No. 6729

January 21, 1972 492 P.2d 989

Appeal from order denying pre-trial petition for writ of habeas corpus. Eighth Judicial

District Court, Clark County; Howard W. Babcock, Judge.

The Supreme Court held that although affidavit by means of which state secured

continuance of a scheduled preliminary examination contained inaccuracies and prosecutor

had been guilty of lack of diligence in preparation of affidavit, accused was not entitled to

writ of habeas corpus discharging her from restraint and prohibiting further prosecution.

Affirmed.

Robert G. Legakes, Public Defender, and Thomas D. Beatty, Deputy Public Defender,

Clark County, for Appellant.

Robert List, Attorney General, Roy A. Woofter, District Attorney, and Charles L. Garner,

Chief Deputy of Appeals, Clark County, for Respondent.

Habeas Corpus.

Although affidavit by means of which state secured a scheduled preliminary examination contained

inaccuracies and prosecutor had been guilty of lack of diligence in preparation of affidavit,

accused was not entitled to writ of habeas corpus discharging her from restraint and

prohibiting further prosecution.

88 Nev. 14, 15 (1972) Downey v. Sheriff

had been guilty of lack of diligence in preparation of affidavit, accused was not entitled to writ of habeas

corpus discharging her from restraint and prohibiting further prosecution. DCR 21.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

The sole issue presented by this appeal is whether or not the appellant is entitled to a writ

of habeas corpus discharging her from restraint and prohibiting further prosecution when the

state secures a continuance of a scheduled preliminary examination by means of an affidavit

1

containing inaccurate statements of fact.

2

Upon the strength of the state's affidavit, the

magistrate granted a two week continuance. The appellant petitioned for a writ of habeas

corpus, which was denied, and this appeal followed.

The issue thus presented must be answered in the negative. While the prosecutor was

guilty of a lack of diligence in the preparation of the affidavit, this is not a case where a

continuance was sought without the required affidavit. Cf. Hill v. Sheriff, supra, and Stockton

v. Sheriff, 87 Nev. 94, 482 P.2d 285 (1971). Neither is it a case where the prosecutor willfully

disregarded important procedural rules. Cf. Maes v. Sheriff, 86 Nev. 317, 468 P.2d 332

(1970). Nor is this a case where the prosecutor exhibited a conscious indifference to rules of

procedure affecting the accused's rights. Cf. State v. Austin, 87 Nev. 81, 482 P.2d 284 (1971).

While the affidavit contained inaccuracies, the record does not reveal that either the

prosecutor or counsel for the appellant were aware of them at the time the continuance was

sought. Because both the motion for a continuance and the supporting affidavit appeared

proper on their face, the magistrate was entitled to rely on them. Consequently, the two week

continuance which was granted upon the strength of the motion and supporting affidavit was

justified, and the district court did not err in denying habeas relief.

Affirmed.

____________________

1

As required by DCR 21 and Hill v. Sheriff, 85 Nev. 234, 452 P.2d 918 (1969).

2

While no contention is made that the state intentionally set forth false statements or that the affidavit was

made in bad faith, it is conceded that the content of the affidavit was inaccurate due to a failure of the prosecutor

to examine all sources of information available to him.

____________

88 Nev. 16, 16 (1972) Las Vegas Ins. Adjusters v. Page

LAS VEGAS INSURANCE ADJUSTERS, a Nevada Corporation, Appellant, v. LEHMANN

M. PAGE, Respondent.

No. 6615

January 24, 1972 492 P.2d 616

Appeal from order of Eighth Judicial District Court, Clark County, granting summary

judgment; Joseph S. Pavlikowski, Judge.

Affirmed.

John Marshall, of Las Vegas, for Appellant.

Denton & Monsey, of Las Vegas, for Respondent.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

We affirm the summary judgment entered below since there is no genuine issue as to any

material fact. NRCP 56(c). The appellant's claim for money from the respondent was

compromised and settled by written agreement between them. The appellant's effort to avoid

the binding effect of that agreement is denied by the record which shows conclusively that the

agreement was entered into with full knowledge of all relevant facts.

Affirmed.

____________

88 Nev. 16, 16 (1972) Jasper v. Sheriff

MARJORIE JASPER, Appellant, v. SHERIFF, CLARK

COUNTY, NEVADA, Respondent.

No. 6694

January 24, 1972 492 P.2d 1305

Appeal from an order denying a pre-trial petition for a writ of habeas corpus. Eighth

Judicial District Court, Clark County; Howard W. Babcock, Judge.

The district court denied petition, and petitioner appealed. The Supreme Court held that

finding of magistrate that affidavit in support of state's motion for continuance failed to show

exercise of due diligence to secure attendance of an absent witness did not operate to preclude

magistrate from granting a continuance and was not a basis for obtaining habeas corpus relief

on ground that magistrate was without power to order a continuance once finding was

made, where magistrate interrogated prosecutor, though not on oath, and ruled on oral

representations made by him that state had complied with requirements of rule; however,

in the future, magistrate must take supplementary testimony from prosecutor by means

of sworn testimony.

88 Nev. 16, 17 (1972) Jasper v. Sheriff

a continuance once finding was made, where magistrate interrogated prosecutor, though not

on oath, and ruled on oral representations made by him that state had complied with

requirements of rule; however, in the future, magistrate must take supplementary testimony

from prosecutor by means of sworn testimony.

Affirmed.

Robert G. Legakes, Public Defender, and Morgan D. Harris, Deputy Public Defender,

Clark County, for Appellant.

Robert List, Attorney General, Roy A. Woofter, District Attorney, and Charles L. Garner,

Chief Deputy of Appeals, Clark County, for Respondent.

1. Criminal Law.

Where preliminary examination was scheduled for April 29, 1971, but on April 28, 1971 prosecutor filed

a motion for a continuance, supported by an affidavit, in which it was alleged that one of state's witnesses

would be out of town until May 15, 1971, and would not be able to testify, where, based on oral

representations made by prosecutor in response to magistrate's inquiry a continuance was ordered until

May 17, 1971, and where record did not reflect granting of any prior continuances, and no contention was

made below, or in appellate proceedings, that petitioner had been denied her right to a preliminary

examination within fifteen days, fifteen day rule was waived. NRS 200.070.

2. Habeas Corpus.

Finding of magistrate that affidavit in support of state's motion for continuance failed to show exercise of

due diligence to secure attendance of an absent witness did not operate to preclude magistrate from

granting a continuance and was not a basis for obtaining habeas corpus relief on ground that magistrate was

without power to order a continuance once finding was made, where magistrate interrogated prosecutor,

though not on oath, and ruled on oral representations made by him that state had complied with

requirements of rule. DCR 21.

3. Criminal Law.

Where, in determining existence of good cause, magistrate supplements information obtained from

affidavit in support of state's motion for continuance by oral representations made by prosecutor in

response to magistrate's inquiry, magistrate must in future take supplementary testimony from prosecutor

by means of sworn testimony. DCR 21.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

By criminal complaint the appellant was charged with two counts of involuntary

manslaughter under NRS 200.070, in that on November 17, 1970, she operated a motor

vehicle while under the influence of intoxicating liquor and failed to stop in obedience to a

traffic control device, colliding with another vehicle and killing two of its occupants.

88 Nev. 16, 18 (1972) Jasper v. Sheriff

that on November 17, 1970, she operated a motor vehicle while under the influence of

intoxicating liquor and failed to stop in obedience to a traffic control device, colliding with

another vehicle and killing two of its occupants.

[Headnote 1]

A preliminary examination was scheduled for April 29, 1971.

1

On April 28, 1971, the

prosecutor filed a motion for a continuance, supported by an affidavit,

2

in which it was

alleged that one of the state's witnesses was out of town until May 15, 1971, and not able to

testify. Neither the motion nor the supporting affidavit have been made a part of the record on

appeal, but from the transcript of the preliminary examination it is evident that no attempt had

been made to secure the attendance of the absent witness until the day before, when a

subpoena was issued but not served. The prosecutor, in response to the magistrate's inquiry,

stated that the reason for the delay in attempting to secure the attendance of the witness was

that the coroner's office did not supply him with the name of the witness

3

until the day

before the scheduled preliminary examination, although at least two prior requests were made

to the coroner's office for the information.

The magistrate denied the state's motion for a continuance upon his finding that the

supporting affidavit failed to show due diligence. However, based upon the oral

representations made by the prosecutor in response to the magistrate's inquiry, a continuance

was ordered until May 17, 1971. The appellant petitioned for a writ of habeas corpus on the

grounds that the magistrate was without power to order a continuance after a finding that

there was not a showing of due diligence in the supporting affidavit. The district court denied

the writ and the appellant appealed.

Without the benefit of the affidavit as part of the record on appeal we are not able to

determine whether or not it met the requirements of DCR 21. The magistrate ruled that it did

not, in that it failed to show the exercise of due diligence to secure the attendance of the

absent witness.

____________________

1

Since the record does not reflect the granting of any prior continuances, and no contention was made below,

or in these appellate proceedings, that the appellant had been denied her right to a preliminary examination

within fifteen days, it is apparent that there had been a waiver of the fifteen day rule under NRS 171.196(2).

2

As required by DCR 21 and Hill v. Sheriff, 85 Nev. 234, 452 p.2d 918 (1969).

3

The absent witness was a physician, apparently the only person available who could testify as to the cause of

death of the accident victims.

88 Nev. 16, 19 (1972) Jasper v. Sheriff

the attendance of the absent witness. However, the magistrate interrogated the prosecutor and

ruled that, upon the oral representations made by him, the state had complied with the

requirements of DCR 21.

While the prosecutor was not sworn by the magistrate, the procedure used by the

magistrate to ascertain facts in addition to those supplied by the affidavit was substantially as

suggested by our opinion in Bustos v. Sheriff, 87 Nev. 622, 491 P.2d 1279 (1971). There we

said . . . [I]t is reasonably clear that the prosecutor could have shown good cause had the

magistrate required his sworn testimony in lieu of affidavit, and since this method of showing

cause has not heretofore been suggested we shall not fault the magistrate for granting a

continuance in this instance. . . .

[Headnotes 2, 3]

The thrust of the habeas petition below, and in these appellate proceedings, was not that

the prosecutor's oral representations failed to show good cause, but simply that upon a failure

of the affidavit to show good cause the magistrate was without power to grant a continuance.

We reject that contention and we approve the procedure used by the magistrate to supplement

the deficiencies of the affidavit.

4

Consequently, upon the record before us we cannot fault

either the magistrate's order for a short continuance, or the district court's denial of habeas.

Affirmed.

____________________

4

Hereafter, however, the magistrate must take supplementary testimony from the prosecutor by means of

sworn testimony.

____________

88 Nev. 19, 19 (1972) Moss v. State

LARRY MAURICE MOSS, Appellant, v. THE STATE

OF NEVADA, Respondent.

No. 6590

January 25, 1972 492 P.2d 1307

Appeal from judgments of conviction of the Second Judicial District Court, Washoe

County; Llewellyn A. Young, Judge.

The district court found defendant guilty of obtaining money by false pretenses and of

attempting to obtain money by false pretenses, and he appealed. The Supreme Court,

Thompson, J., held that the Sixth Amendment was not violated by on-the-scene identification

of defendant by 88-year-old widow (from whom defendant had on previous day obtained

money by false pretenses and who, when he was met by a police officer at victim's door,

was again attempting to obtain money by false pretenses) immediately following

apprehension of defendant by the police.

88 Nev. 19, 20 (1972) Moss v. State

pretenses and who, when he was met by a police officer at victim's door, was again

attempting to obtain money by false pretenses) immediately following apprehension of

defendant by the police.

Affirmed.

James F. Sloan, of Reno, for Appellant.

Robert List, Attorney General, Robert E. Rose, District Attorney, and Kathleen M. Wall,

Deputy District Attorney, Washoe County, for Respondent.

1. Criminal Law.

Sixth Amendment was not violated by on-the-scene identification of defendant by 88-year-old widow

(from whom defendant had on previous day obtained money by false pretenses and who, when he was met

by a police officer at victim's door, was again attempting to obtain money by false pretenses) immediately

following the apprehension of defendant by the police. NRS 205.380, 208.070; U.S.C.A.

Const.Amend. 6.

2. Criminal Law.

Although a pretrial photographic identification of defendant by two bank employees should not have been

conducted in the absence of his counsel, the in-court identification testimony by the bank employees was

properly received, where each employee testified explicitly that his in-court identification was wholly

independent of the photographic identification and was based upon observations of the defendant when he

was in the bank.

3. Criminal Law.

Where counsel for defendant, charged with obtaining money by false pretenses and with attempting to

obtain money by false pretenses, failed to object at trial to several telephone conversations which the victim

had had with Mr. Allen and which linked defendant with the acts constituting the crimes with which he

was charged, defense counsel could not on appeal question the admissibility of testimony relating to those

conversations.

4. Criminal Law.

Prosecutor's comment, during summation to the jury, that the State's evidence was uncontradicted did not

infringe upon defendant's Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 5.

OPINION

By the Court, Thompson, J.:

A jury convicted Moss of obtaining money by false pretenses [NRS 205.380], and

attempting to obtain money by false pretenses [NRS 208.070]. We affirm the convictions

since none of the assigned errors has merit.

88 Nev. 19, 21 (1972) Moss v. State

An 88-year-old widow, Alma Clarke, received a telephone call from a Mr. Allen who

represented himself to be a federal bank inspector. He informed Mrs. Clarke that someone at

the bank was tampering with her account and asked her to withdraw $4,800 to facilitate the

culprit's capture. She did so. Upon returning to her home the telephone rang. The call was

from Mr. Allen who said that his deputy Mr. Baggs would be by shortly to pick up the

money. Mr. Baggs soon arrived, received the money from Mrs. Clarke and departed. Mrs.

Clarke became suspicious, telephoned the bank, and was instructed to contact the police. The

officer requested her to let him know should she receive another call from Allen.

The next day Allen called and informed Mrs. Clarke that her money had been

redeposited, but that another withdrawal was necessary in order to catch the culprit. She

notified the police and her home was placed under surveillance. A sham transaction was

arranged with the bank whereby Mrs. Clarke would go through the motions of withdrawing

$4,500. The police were at her home when she returned from the bank. Within an hour they

observed an automobile drive in to the alley near her home. Two men were in the car. One of

them exited from the car and walked to the front door of Mrs. Clarke's home where he was

confronted by a police officer. Mrs. Clarke came to the door and identified that man, the

appellant here, as the man to whom she had delivered $4,800 the day before using the name

of Baggs. He was thereupon arrested and advised of his rights.

It is apparent that there exists substantial evidence to support each conviction and the

assigned error on that basis is dismissed out of hand. We turn briefly to consider the other

claimed errors.

[Headnote 1]

1. The on-the-scene identification of appellant by the victim, in the absence of counsel, is

challenged as violative of the doctrine announced in United States v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218

(1967), and its companion cases of Gilbert v. California, 388 U.S. 263 (1967), and Stovall v.

Denno, 388 U.S. 293 (1967). In Wade, the accused was exhibited to witnesses before trial at a

post-indictment lineup conducted for identification purposes without notice to and in the

absence of the accused's appointed counsel. In these circumstances the court ruled that the

lineup was a critical stage of the criminal proceeding and the accused had the right to the

assistance of counsel. In Gilbert, the Supreme Court applied the doctrine of Wade to state

court trials. And in Stovall, the court denied retroactivity to Wade and ruled that it would

only be applied to confrontations occurring after June 12, 1967.

88 Nev. 19, 22 (1972) Moss v. State

and ruled that it would only be applied to confrontations occurring after June 12, 1967. None

of those cases involved an on-the-scene identification of the suspect by the victim. In Nevada

we have extended the Wade doctrine to embrace a lineup which occurs before the filing of

formal charges if the prosecutorial process has shifted from the investigatory to the

accusatory stage and has focused upon the accused. Thompson v. State, 85 Nev. 134, 138,

451 P.2d 704 (1969); Lloyd v. State, 85 Nev. 576, 460 P.2d 111 (1969).

We have not, however, had occasion to consider an on-the-scene identification of the

suspect by the victim.

1

We hold that the Sixth Amendment is not violated when the

identification by the victim immediately follows apprehension of the suspect by the police.

Here, the appellant was attempting to commit a criminal act when apprehended and

immediately identified. The proximity of the time of the commission of the crime to the time

of confrontation of the appellant and victim was almost instantaneous. Cf. State v. Meeks,

469 P.2d 302 (Kan. 1970); State v. Jordan, 274 A.2d 605 (Sup.Ct.N.J. 1971). The

confrontation here was neither a lineup within the contemplation of Wade, nor a showup

within the intendment of Stovall. Nor can it realistically be said to be so unnecessarily

suggestive and conducive to irreparable mistaken identification as to deny due process.

Stovall v. Denno, supra; McCray v. State, 85 Nev. 597, 460 P.2d 160 (1969).

[Headnote 2]

2. Two employees of the bank made a pretrial photographic identification of the appellant

in the absence of his counsel, and later identified him in court. Each testified explicitly that

his in-court identification was wholly independent of the photographic identification, and was

based upon observation of the appellant when he was in the bank. The court, at the

conclusion of a hearing in the absence of the jury, found that the identification of each

witness had a solid origin independent of the photographs and that such independent origin

was established by clear and convincing evidence. Although the photographic lineup should

not have been conducted in the absence of counsel, Thompson v. State, 85 Nev. 134, 451

P.2d 704 (1969), the in-court identification testimony was properly received.

____________________

1

See: Riley v. State, 86 Nev. 244, 468 P.2d 11 (1970); Tucker v. State, 86 Nev. 354, 469 P.2d 62 (1970);

McCray v. State, 85 Nev. 597, 460 P.2d 160 (1969); Hamlet v. State, 85 Nev. 385, 455 P.2d 915 (1969);

Hampton v. State, 85 Nev. 720, 462 P.2d 760 (1969); Boone v. State, 85 Nev. 450, 456 P.2d 418 (1969).

88 Nev. 19, 23 (1972) Moss v. State

received. Hernandez v. State, 87 Nev. 553, 490 P.2d 1245 (1971); Corbin v. State, 87 Nev.

214, 484 P.2d 721 (1971); Ridley v. State, 86 Nev. 102, 464 P.2d 500 (1970); Wyand v.

State, 86 Nev. 500, 471 P.2d 216 (1970); Carmichel v. State, 86 Nev. 205, 467 P.2d 108

(1970); Lloyd v. State, 85 Nev. 576, 460 P.2d 111 (1969); Thompson v. State, supra.

[Headnote 3]

3. Defense counsel failed to object to several telephone conversations which the victim

had with Mr. Allen. These conversations linked appellant as Mr. Baggs with the acts

constituting the crimes with which he was charged. His effort to now object comes too late.

Wilson v. State, 86 Nev. 320, 468 P.2d 346 (1970).

[Headnote 4]

4. During summation to the jury the prosecutor commented that the State's evidence was

uncontradicted. The comments were within permissible limits. Fernandez v. State, 81 Nev.

276, 402 P.2d 38 (1965). His comments were factually correct, and did not refer to the

accused specifically. The State's case may be contradicted by witnesses other than the accused

if such witnesses exist. Consequently, we will not construe the comments here involved as an

infringement upon the accused's Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination.

Affirmed.

Zenoff, C. J., and Batjer, Mowbray, and Gunderson, JJ., concur.

____________

88 Nev. 23, 23 (1972) State v. Pashos

STATE OF NEVADA, Appellant, v. MICHAEL PASHOS, NORRIS WAYNE

SANDERS, and CHESTER DAVIS SMITH, Respondents.

No. 6778

January 25, 1972 492 P.2d 1309

Appeal from an order dismissing petition for contempt. Eighth Judicial District Court,

Clark County; Joseph S. Pavlikowski, Judge.

Appeal by state from order of the district court dismissing petition for order to show cause

why officers of union should not be held in contempt for failing to appear before State

Gaming Control Board and testify concerning union activities in the gaming industry.

88 Nev. 23, 24 (1972) State v. Pashos

in the gaming industry. The Supreme Court held that State Gaming Control Board had power

to issue subpoenas to compel testimony regarding union activities in the gaming industry.

Reversed.

[Rehearing denied March 14, 1972]

Robert List, Attorney General, and David C. Polley, Deputy Attorney General, for

Appellant.

Peter L. Flangas, of Las Vegas, for Respondents.

States.

State Gaming Control Board had power to issue subpoenas to compel testimony regarding union

activities in the gaming industry. NRS 463.130, subd. 1, 463.140, subd. 5.

OPINION

Per Curiam:

The State Gaming Control Board issued subpoenas directing respondents, officers of the

Union of Gaming and Affiliated Casino Employees Union of America, Local 711, to appear

before the Board and testify concerning union activities in the gaming industry. Respondents

failed to present themselves at the time specified in the subpoenas. The appellant then filed a

petition for an order to show cause why the respondents should not be held in contempt. This

petition was dismissed. The trial judge was of the opinion that the Board was without

jurisdiction to compel testimony regarding union activities in the gaming industry. We

conclude that the Board did possess the power to issue these subpoenas and accordingly

reverse with directions to the trial court to enforce the subpoenas.

The State Gaming Control Board was created by legislative enactment in 1955. The state

public policy sought to be advanced by this agency is declared in the provisions of NRS

463.130(1). To carry out this expressed policy, the Board is given full authority to issue

subpoenas, compel attendance of witnesses, and require testimony under oath. NRS

463.140(5). The Board is not to be frustrated in its efforts to enforce that policy. The rights of

those subpoenaed may be asserted at the time of questioning.

Reversed.

____________

88 Nev. 25, 25 (1972) Meakin v. Meakin

FRANCIS HARDIE MEAKIN, Appellant, v. MARTHA

JANIS MEAKIN, Respondent.

No. 6609

January 26, 1972 492 P.2d 1304

Appeal from order denying reduction in child support, Eighth Judicial District Court,

Clark County; John F. Mendoza, Judge.

Proceeding on appeal from an order of the district court denying ex-husband's motion for

reduction of child support. The Supreme Court, Gunderson, J., held that affidavit, which was

offered in support of ex-husband's motion for reduction of child support, and in which

husband stated that deterioration of his health prevented his practice of dentistry, that he had

to file bankruptcy, and that he was constrained to work as a hospital orderly earning only

$400 per month and thus was unable to meet $750 monthly child support payments, was

legally insufficient, being a mere conclusion.

Affirmed.

George, Steffen & Simmons, of Las Vegas, for Appellant.

David Canter, of Las Vegas, for Respondent.

1. Divorce.

Affidavit, which was offered in support of ex-husband's motion for reduction of child support, and in

which husband stated that deterioration of his health prevented his practice of dentistry, that he had to file

bankruptcy, and that he was constrained to work as a hospital orderly earning only $400 per month and

thus was unable to meet $750 monthly child support payments, was legally insufficient, being a mere

conclusion.

2. Appeal and Error.

Where appellant had not brought up hearing transcript, nor a substitute therefor, Supreme Court would

assume that evidence supported trial court's implicit determinations.

OPINION

By the Court, Gunderson, J.:

On May 8, 1970, appellant obtained a Nevada divorce which provided, among other

things, for child support payments of $750 per month. In January, 1971, our district court,

without stating its reasons, denied a motion by appellant for reduction of child support. This

appeal follows.

88 Nev. 25, 26 (1972) Meakin v. Meakin

[Headnote 1]

1. Appellant argues our district court's refusal to reduce the child support amounts to an

abuse of discretion, contending (a) the deterioration of his health prevents his practice of

dentistry, (b) he has had to file bankruptcy, and (c) he is now constrained to work as a

hospital orderly earning only $400 per month and thus is unable to meet the $750 monthly

child support payments. Except in his brief, the only place in the record where appellant's

contentions are found is in his affidavit of December 10, 1970. In Green v. Green, 75 Nev.

317, 340 P.2d 586 (1959), we held that a wife's affidavit which alleged that she had

insufficient funds was legally insufficient, being a mere conclusion. Appellant's affidavit

before us is within our holding in Green.

[Headnote 2]

2. As appellant has not brought up the hearing transcript [nor a substitute therefor] we

must assume the evidence supported the trial court's implicit determinations. Leeming v.

Leeming, 87 Nev. 530, 490 P.2d 342 (1971); City of Henderson v. Bentonite, Inc., 87 Nev.

188, 483 P.2d 1299 (1971).

Since the record does not establish that the trial court abused its discretion, the judgment is

affirmed.

Zenoff, C. J., and Batjer, Mowbray, and Thompson, JJ., concur.

____________

88 Nev. 26, 26 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

ROBERT A. MAHEU, Individually and Doing Business as ROBERT A. MAHEU

ASSOCIATES, Petitioner, v. THE EIGHTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT OF THE

STATE OF NEVADA, IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF CLARK, DEPT. NO. 6, and

THE HONORABLE HOWARD W. BABCOCK, Judge Thereof, Respondent.

No. 6663

January 28, 1972 493 P.2d 709

Petition for writs of prohibition and mandamus to the Eighth Judicial District Court, Clark

County; Howard W. Babcock, Judge.

The Supreme Court, Gunderson, J., held that entry of ex parte orders staying depositions

noticed by defendant, thereafter denying defendant's motion to vacate order that stayed

deposition,

88 Nev. 26, 27 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

deposition, and then declining to consider any matter except plaintiff's Motion to Stay

pending its determination, all without motions for protective orders seasonably made by any

party or by the person to be examined and upon notice and for good cause shown, denied

defendant's right to take testimony of any person, including a party, by deposition upon oral

examination or written interrogatories, and entitled defendant to writ of mandamus

commanding vacation of order staying deposition of plaintiff through its managing agent.

Writs of prohibition and mandamus issued in accord with opinion.

Mowbray, J., dissented.

[Rehearing denied March 14, 1972]

Morton Galane, of Las Vegas, for Petitioner.

Davis & Cox, of New York City; Morse, Foley and Wadsworth, of Las Vegas, for

Respondent.

1. Prohibition.

Prohibition will arrest proceedings in aid of an order that is not binding on the petitioner. NRS 34.320.

2. Appeal and Error; Prohibition.

Where defendant posted proper appeal bond in connection with his appeal from preliminary injunction

requiring defendant to return plaintiff 's business records, and moved for an order fixing supersedeas

bond necessary to obtain a stay during appeal, denial of motion was improper, and proceedings on plaintiff

's motion for stay of all proceedings by defendant until defendant complied with the prior order to return

records to plaintiff and for an extension of time to respond to pleadings until after defendant complied with

prior order were in excess of jurisdiction, entitling defendant to writ of prohibition with respect to such

proceedings. NRS 34.320; NRCP 73(d), (d)(2), (d)(4).

3. Motions.

Any special motion involving judicial discretion that affects rights of another, as contrasted to motions

of course, must be made on notice even where no rule expressly requires notice, except when

requirement is statutorily altered to meet extraordinary situations. NRCP 26(a), 65(b).

4. Discovery; Mandamus.

Entry of ex parte orders staying depositions noticed by defendant, thereafter denying defendant's

motion to vacate order that stayed deposition, and then declining to consider any matter except plaintiff's

Motion to Stay pending its determination, all without motions for protective orders seasonably made by

any party or by the person to be examined and upon notice and for good cause shown, denied defendant's

right to take testimony of any person,

88 Nev. 26, 28 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

any person, including a party, by deposition upon oral examination or written interrogatories, was

improper and entitled defendant to writ of mandamus commanding vacation of order staying deposition of

plaintiff through its managing agent. NRS 34.160; NRCP 6(d), 26(a), 30(b), 65(b).

OPINION

By the Court, Gunderson, J.:

In these original proceedings, Robert A. Maheu seeks certain extraordinary writs directed

to the respondent court, in which litigation is pending that involves Maheu, Hughes Tool

Company (HTCo), Howard R. Hughes (HTCo's sole shareholder), and others. Specifically,

Maheu requests these writs:

(1) prohibition arresting proceedings on a Motion for a Stay and for an Extension of

Time, filed by HTCo;

(2) mandamus commanding respondent to vacate an ex parte order that purports to stay the

deposition of HTCo by its managing agent, Howard R. Hughes;

(3) mandamus commanding respondent to furnish Maheu opportunity to file and have

entertained a motion for the imposition of a conditional sanction to ensure the appearance of

Howard R. Hughes for the taking of his deposition; and

(4) mandamus commanding respondent to vacate that provision of an Order Sealing

Exhibit which curtails disclosure of the contents of certain documents.

Of these requests, we grant the first two for reasons stated in this Opinion. With those matters

determined by us, we are confident respondent will promptly consider and decide any motion

for a conditional sanction Maheu may address to it; thus, we believe Maheu will now have a

plain, speedy and adequate remedy concerning the matter involved in his third request;

therefore we deny it, without prejudice. While Maheu's counsel may have acquiesced in the

court's entry of an order precluding disclosure of his exhibit, we have no doubt that, subject to

appropriate safeguards, Maheu's counsel is nonetheless entitled to copies thereof to prepare

his case, and during deposition should be allowed to examine Hughes on the original

documents. However, again, we are confident the court will now allow such access upon

proper application; thus Maheu's fourth request for relief is also denied, without prejudice.

A complaint is pending in the respondent court by Robert A. Maheu, plaintiff, against

Chester C. Davis, Frank William Gay, and C. J. Collier, Jr., as defendants, claiming damages

for wrongful interference with Maheu's alleged right to control certain business properties.

88 Nev. 26, 29 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

certain business properties. Another complaint is pending in the name of HTCo, as plaintiff,

seeking an injunction and damages against Maheu, as defendant, for wrongful refusal to

surrender control of business properties and records. In addition to pleading defenses to

HTCo's complaint, Maheu has stated a counterclaim against Hughes and HTCo.

On December 12, 1970, while conducting combined hearings on motions for preliminary

injunction filed by Maheu and HTCo, the court entered an Order Sealing Exhibit, providing

that a documentary exhibit offered by Maheu be sealed in an envelope, which should not be

reopened except on application to the court, and that Maheu was prohibited from making

any further disclosure, dissemination or other use of the exhibit.

On December 24, 1970, the court entered a preliminary injunction from which Maheu has

taken an appeal, the merits of which are not before us. The injunction contains provisions

requiring Maheu to return records, with which Maheu claims to have complied to the extent

he understands the obligations created thereby.

1

On December 31, 1970, Maheu served HTCo's counsel with notice under NRCP 26(a),

advising them he would take the deposition of HTCo, by its managing agent, Howard R.

Hughes, at 10:00 a.m., January 11, 1971, at the office of Maheu's attorney. No one appeared

pursuant to the notice. Instead, at 10:33 a.m. on January 11, HTCo's counsel filed a paper

styled Motion to Vacate Notice to Take Deposition, asserting that (1) the discovery sought

was premature, (2) the discovery was not in conformity with applicable provisions of the

Nevada Rules of Civil Procedure nor with other applicable rules of law, and (3) HTCo may

not be compelled to produce Howard R. Hughes as its managing agent. The same day, at

10:35 a.m., HTCo's counsel procured an ex parte order, purporting to stay the deposition

until further order of the court following hearing and determination of said Motion. The

motion was never heard.

On January 11, Maheu applied for an order directing the amount of the supersedeas bond

to be posted by him to obtain a stay of the preliminary injunction pending his appeal.

____________________

1

Among other things, the preliminary injunction provides:

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that defendants, their respective agents, servants, employees and attorneys,

and all persons in active concert and participation with any of them, shall forthwith return or cause the return to

plaintiff of all books, documents, records and communications of plaintiff or pertaining directly or indirectly to

the business operations or affairs of plaintiff, including all copies or other reproductions [sic] of same, and all

other property belonging to plaintiff, as may be in the possession, custody or control of defendants directly or

indirectly.

88 Nev. 26, 30 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

amount of the supersedeas bond to be posted by him to obtain a stay of the preliminary

injunction pending his appeal. January 14, the court denied this application.

On January 19, at 5:14 p.m., counsel purporting to act only for HTCo filed the Motion for

a Stay and for an Extension of Time that is the subject of Maheu's application for a writ of

prohibition. This motion asked the court: (1) for a stay of all actions, proceedings,

processes and other activities by or on behalf of Robert A. Maheu. . . other than for

compliance with the prior orders of this court dated December 12 and 24, 1970, relating to

certain documents and other property to be returned to HTCO, until MAHEU has fully

complied with and satisfied the Court as to his compliance with said prior orders of this

court; and (2) for an extension of time for any party to move, answer or otherwise respond

to pleadings until after Maheu shall have fully complied and satisfied the court as to his

compliance with said prior orders of this Court.

2

By ex parte order filed at 5:19 p.m., the

court extended the time of any party to plead, as requested by the motion, and stayed

depositions of Frank W. Gay and Chester C. Davis (respectively noticed by Maheu for

January 25 and February 1) until further order of this Court following hearing and

determination of the Motion to Stay.

On February 5, Maheu served another notice to depose Hughes, and moved the court to

vacate its ex parte stay order of January 11. March 3, the court denied Maheu's motion

without prejudice.

April 1, the court conducted a conference to schedule the order in which pending matters

would be heard. The court decided, over protests by Maheu's counsel, that it would not

consider any other matters until such time as it had heard and determined HTCo's "Motion for

a Stay and for an Extension of Time."

____________________

2

The grounds for this Motion for Stay were:

1. MAHEU has failed and refused to comply with the prior orders of this Court;

2. substantial rights of HTCO in the above cases are materially and adversely affected so long as MAHEU

fails to comply with the prior orders of this Court relating to the return of documents and property belonging to

HTCO;

3. MAHEU is not entitled to the use or protection of the rules, procedures or processes of this Court in

connection with the above cases so long as he is defying the prior orders of this Court; and

4. the conduct of MAHEU is contumacious and tends to make a mockery of the rules, procedures and

orders of this Court. It is not only inequitable but prejudicial to HTCO to require the parties involved in the

above cases to proceed with the litigation of the issues raised by MAHEU so long as MAHEU fails and refuses

to comply with the outstanding orders of this Court.

88 Nev. 26, 31 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

determined HTCo's Motion for a Stay and for an Extension of Time. Thereafter, the court

held hearings at which it permitted HTCo's counsel to call numerous persons to interrogate

them concerning the nature and quantity of records removed from premises of HTCo, where

Maheu and his company had conducted business (including managerial services for HTCo)

until HTCo undertook to terminate its relationship with Maheu. These proceedings continued

from time to time until June 12, when our court stayed them to consider the petition now

before us.

I

[Headnotes 1, 2]

Under NRS 34.320, the writ of prohibition arrests the proceedings of any tribunal,

corporation, board or person exercising judicial functions, when such proceedings are without

or in excess of jurisdiction. As a corollary, prohibition will arrest proceedings in aid of an

order that is not binding on the petitioner. See: State ex rel. Friedman v. Dist. Ct., 81 Nev.

131, 399 P.2d 632 (1965), and Culinary Workers v. Court, 66 Nev. 166, 207 P.2d 990 (1949),

both granting prohibition against proceedings in aid of a restraining order improperly issued

without a bond. Thus, if the injunction's provisions requiring Maheu to return records failed

for any reason to bind him, then prohibition lies against proceedings instituted to enforce

those provisions.

Maheu contends that proceedings predicated upon mandatory provisions of the preliminary

injunction are therefore in excess of the district court's jurisdiction because although he

appealed, posted a proper appeal bond, and moved for an order fixing the supersedeas bond

necessary to obtain a stay during appeal, the district court unlawfully denied his motion. If the

injunction's mandatory provisions are deemed to direct the assignment or delivery of

documents or personal property within the meaning of NRCP 73(d)(2), Maheu urges, then

under that rule he had an absolute right to enter a bond [i]n lieu of assignment and delivery.

However, if NRCP 73(d) does not require a supersedeas bond, Maheu argues, his appeal itself

effected an automatic stay, because NRCP 73(d)(4) states [i]n cases not provided for. . . the

giving of an appeal bond . . . shall stay proceedings in the court below upon the judgment or

order appealed from. As Maheu in fact sought to have the court fix the supersedeas required

of him, we may assume the case is governed by NRCP 73(d)(2).

The pertinent part of that rule was derived from Section 407 of our 1911 Civil Practice

Act, and is in substantially the same form today as when this court decided State ex rel.

88 Nev. 26, 32 (1972) Maheu v. District Court

form today as when this court decided State ex rel. Pacific Reclamation Co. v. Ducker, 35

Nev. 214, 127 P. 990 (1912). There we said: On an appeal from a mandatory injunction

requiring defendants to deliver property to plaintiffs, as in this case, an appeal from the order

entitled the defendants, as a matter of right, upon the filing of a proper stay bond, to a stay of

proceedings under the injunction. In such a case, the fixing of the amount of the stay bond is

not a matter of discretion with the trial court. 35 Nev., at 227; 127 P., at 994; accord, Dodge

Bros. v. General Petroleum Corp., 54 Nev. 245, 10 P.2d 341 (1932). We can hardly depart

from our prior rulings, for they not only appear correct, but have been part of our practice for

more than half a century; the statute they interpreted was re-adopted by our legislature as part

of our 1937 new trials and appeals act (Stat. of Nev. 1937, ch. 32, p. 53, at p. 59); this court

itself adopted those provisions without material change, upon recommendation of our