Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Law - Meaning of Acquiscence

Hochgeladen von

PameswaraCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Law - Meaning of Acquiscence

Hochgeladen von

PameswaraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

If2

PLEA

OF

DOMESTIC

JURISDICTION

(10) The special United States fonn of reservation, 'matters essentially within domestic jurisdiction as detennined by the United States', appears to be incompatible with the Statute of the Court. If so, the result is to invalidate the whole submission to jurisdiction in the instrument, not the reservation by itself. In consequence, instruments containing such a reservation appear to provide a basis for establishing jurisdiction on the principle of the forum prorogatum but no more. In general, it seems that the doctrine of the reserved domain, as a limit upon the jurisdiction of legal tribunals, is both artificial and destructive of the avowed object of the acceptance of their jurisdiction. For it confuses jurisdiction with substantive rights and obligations. It tends to give an air of respectability to what is nothing more than a refusal to allow international obligations to be judicially enforced by a spurious appeal to a constitutional doctrine. If given wide scope it tends to emasculate the vital principle of international law that a State may not plead its own domestic law-including its constitutional law-as an excuse for not performing its international obligations. The Nationality Decrees Opinion, by insisting that the reserved domain begins where international law ends, brought these evil tendencies under control. It is devoutly to be hoped that the new Court, by declaring, when occasion arises, the incompatibility of the United States fonn of reservation with the Statute and by refusing to surrender treaty obligations to the reserved domain under the Charter formula, may largely hold the ground won by the Court in that justly renowned Opinion.

THE SCOPE OF ACQUIESCENCE INTERNATIONAL LAW

IN

By I. C. MAcGIBBON, M.A., LL.B. (EDINBURGH) Meaning of the term 'acquiescence' ACQUIESCENCE, in the accepted dictionary sense of tacit agreement or consent, is essentially a negative concept. In the present article it is used to describe the inaction of a State which is faced with a situation constituting a threat to or infringement of its rights: it is not intended to connote the forms in which a State may signify its consent or approval in a positive fashion. Acquiescence thus takes the form of silence or absence of protest in circumstances which generally call for a positive reaction signifying an objection. The scopeof the doctrine of acquiescence Rights which have been acquired in clear conformity with existing law have no need of the doctrine of acquiescence to confirm their validity. However, the line which divides conduct which international law permits from that which it prohibits is in many cases not susceptible of precise delimitation. A course of action which in one period may have been expressly prohibited may, by dint of its continued repetition coupled with the consent of other States, be acceptable under the rules obtaining in a later period. It is not surprising that, in a system of law which is not fully developed, the extent to which a novel practice may be regarded as being in conformity with existing law should be unpredictable. In the absence of a satisfactory compulsory procedure for authoritative judicial ascertainment the legality of such practices may depend upon the measure in which they enjoy the exp~ess approval of other States, or, in the course of time, their acquiescence. Tribunals may be called upon to resolve the conflict inherent in the rival claims to consideration of the maxims ab injuria jus non oritur and ex factis jus oritur. It is the purpose of this article to indicate the circumstances in which the doctrine of acquiescence may assist in this reconciliation. Acquiescence operates in the sphere to which the maxim ex injuria jus non oritur is least applicable, that is, where the vindication of a claim or course of action depends on the consent of the States affected. The presumption of consent which may be raised by silence is strengthened in proportion to the length of the period during which the silence is maintained. The passage of time is an essential element in prescriptive and historic rights; in the fonnation of rules of customary international law it

148 SCOPE OF ACQUIESCENCE

IN INTERNATIONAL

LAW

SCOPE OF ACQUIESCENCE

IN INTERNATIONAL

LAW

'49

elevate the concept of estoppel to the rank of one of the 'general principles of Jaw recognized by civilized nations'. The principle of estoppel featured in the jurisprudence of the Permanent Court of International Justice in the case of the Serbian Loans' and, more prominently, in the case concerning the Legal Status of Eastern Greenland.' The principle was also recognized, although not applied, in the Award in the Tinoco Arbitratwn between Great Britain and Costa Rica.J The main obstacle to the acceptance of the concept of estoppel as a principle of international law may weJl have been the"long-prevalent belief that it was a technical rule of evidence and, .therefore, unsuited to the 'rough jurispsudence of nations'. The changing climate of opinion may be gauged from the reconsideration given to the nature of estoppel by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Canada and Donu'nion Sugar Company, Ltmited v. Canadian National (West IndUs) Steam$hips, Limited.~ The Board quoted with approval Sir Frederick Pollock's description of the doctrine of estoppel as 'a simple and wholly untechnical conception, perhaps the most powerful and flexible instrument to be found in any system of courtjurisprudence',s and went on to state: 'Estoppel is often described as a rule of evidence, as, indeed, it may be so described. But the whole concept is more correctly viewed as a substantive rule of law.'6 The tribunals before which the doctrine was canvassed accepted it by implication and without. comment, approaching the solution of the problem concerned in the way in which counsel had presented it to them. The doctrine has been invoked in varying forms over a period of a century and a half and although there have been occasions on which it has been held to be inapplicable to the facts its jurisprudential basis has been u,nchallenged.'

=gnition of the pn.lciple that a State cannot blpw hot and cold-all.gans contraria non audinrJus "t' (this Y.ar Book, 5 (1914), p. 35). I P.C.J.J., Series A, Nos. 20/21, pp. 38-39. The principle was approved by the Court but the circumstances were not such as to warrant its application. The Court pointed out that 'no sufficient basis has been shown for applying the principle' of estoppel, and drew atteqtion to the lack of constituent elements of estoppel, noting the absence of any 'clear and unequivocal representation by the bondholders upon which the debtor State Was entitled to rely and has relied' and of any 'change in position on the part of the debtor State.' -(Ibid., p. 39.) 2 P.C.I.J., Series A/B, No. 53. Norway maintained that the attitude of Denmark when seeking recognition of her position in Greenland from other States between 1915 and 1911 \vas inconsistent with the possession of sovereignty at that time and that DeIUD8Ik was therefore estopped from alleging a long-established sovereignty over the whole of Greenland (ibid., p. 45). The Court, however, found that the circumstances provided no ground for holding Denmark thus estopped (i6id., p. 61). The Court observed that by accepting as binding several treaties 'Norway reaffirmed tru.t she recognized the whole of Greenland as Danish; and thereby she has debarred herself from ~ntesting Danish sovereignty. . .' (ibid., pp. 68-{)9). The Court further said: 'It follows that, as a result of the understanding involved in the Ihlen declaration of July 22nd, 1919, Norway is under an obligation to refrain from contesting Danish sovereignty over Greenland as a whole, and, a jortwri to refrain from occupying a part of Greenland' (ibid., p. 73). J See AmnicanJournal of International Law, 18 (1924), pp. 155-'7. . [1947] A.C. 46. , Ibid., p. 55. 6 Ibid., p. 56.

7 The United States argued in the Chamizal Arbitration that Mexico was estopped from

In the dispute between Great Britain and the United States concerning the Titk to Islands in Passamaquoddy Bay, the concluding passage of the case of Great Britain observed that, in view of the silence of the United States with regard to the island of Grand Manan for some ~nty-three -years, and the admission by the United States of the fact of British settlement and jurisdiction over the island during that period, 'It may admit of some doubt whether this profound silence. . . ought not now to preclude all further claim to it on their part, even though their pretensions might

.,

originally have had some foundation'; I and the doubt was supported, the

case continued, by the principle laid down by the Agent for the United States in his argument before the Commissioners under Article IV of the Treaty of 1794 (the Treaty of Ghent), in which he contended that, had the State of Massachusetts remained silent spectators of the improvements made upon the British Settlement on territory claimed by the l; nited States, that would have indicated that the State of Massachusetts had no claim to the territory.2 An extract from the draft of a letterJ from Earl Granville to Musurus Pasha in 1884 referring to the disputed right of a British shipping company to operate vessels on the Tigris and Euphrates, in the context of a disagreement concerning the terms of the Agreement of 1846 concerning general rights of navigation, employs a similar argument. The right was claimed by virtue of the terms of a Vizirialletter of 1861. Earl Granville pointed out that the company had enjoyed that privilege ever since 1861 with the knowledge and acquiescence of the Porte. The absence of protest during that period showed, according to Earl Granville, that the attitude of the Porte had not been, as alleged by Musurus Pasha, one of friendly tolerance,4 but one of acquiescence in a claim of right on the faith of which the company had made large capital investments. 'Whatever may be the true construction of the Agreement of 1846 as to the general right of navigation', the letter adds, 'Her Majesty's Government consider that the attitude of the Porte during the last ~enty-two ~rs debars them from now disputing the validity of the rights clatmed and exercised by the Company under the

asserting title by reason of the long 'undisturbed, uninterrupted, and unchallenged possession' of the disputed territory by the United States. Since it was held that in the circumstances of the case the failure of Mexico to protest did not amount to acquiescence, the question of the application of the doctrine of estoppel did not directly arise. Its validity, however, was not quesIioned by Mexico or by the Commissioners. (The Award is printed in American Journal of /nter,wtiOlwl Law, 5 (1911), pp. 785 ff.) I See Moore, /ntematio,w[ Adjudications (Modem Series), vol. vi, p. 195.

1

See below, p. 161.

J Quoted in McNair, Th. Law of T"at~s (1938), pp. 49-50.

. The dissenting Judges in the case concerning Rights of Nationals of the United Statn In Aloroceo held similarly that the conduct of the French Government which knew of the United States claim to exercise capitulatory rights, and, in spite of their knowledge, continued the old practice withou.t any reservation, was not due merely to 'gracious tolerance' (J.G.J. Rrf>orts 11)51, p. 111).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Believing in Allah in The Unseen by Dr. Mohsen El-GuindyDokument4 SeitenBelieving in Allah in The Unseen by Dr. Mohsen El-GuindyPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- ManagementDokument44 SeitenManagementVinod Kumar ChandrasekaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Contemporary ManagementDokument55 SeitenContemporary ManagementOlga GoldenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Fundamental of ManagmentDokument44 SeitenFundamental of ManagmentKuldeep JangidNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- KashfulMahjoob enDokument527 SeitenKashfulMahjoob enAyaz Ahmed KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- 2016 - Irish Govt - Cost Control Price Variation ClausesDokument45 Seiten2016 - Irish Govt - Cost Control Price Variation ClausesPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hazrat Ali - The Revelation of The VeiledDokument7 SeitenHazrat Ali - The Revelation of The VeiledPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Navigant - Concurrent Delay Compare English & US LawDokument13 SeitenNavigant - Concurrent Delay Compare English & US LawPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- 2010 Condition PrecedentsDokument2 Seiten2010 Condition PrecedentsPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Future of Forensic Schedule Delay Analysis PDFDokument5 SeitenFuture of Forensic Schedule Delay Analysis PDFArif ShiekhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A2014 Keating Causation in LawDokument18 SeitenA2014 Keating Causation in LawPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Sufi Ritual The Parallel Universe by Ian Richard NettonDokument116 SeitenSufi Ritual The Parallel Universe by Ian Richard NettonAli Azzali100% (8)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- 93-Methods of Delay Analysis Requirements and DevelopmentsDokument27 Seiten93-Methods of Delay Analysis Requirements and DevelopmentsSalim Yangui100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Navigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1Dokument7 SeitenNavigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1PameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- p2014 - Common Sense Approach To Global ClaimsDokument31 Seitenp2014 - Common Sense Approach To Global ClaimsPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Navigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1Dokument7 SeitenNavigant ConcurrentDelays in Contracts Part1PameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Navigant - ConcurrentDelays & CriticalPathDokument10 SeitenNavigant - ConcurrentDelays & CriticalPathPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jan15 FenElliott43 - Nec3 - Issuing NoticesDokument4 SeitenJan15 FenElliott43 - Nec3 - Issuing NoticesPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Navigant Concurrent Delay South American ExperienceDokument5 SeitenNavigant Concurrent Delay South American ExperiencePameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Construction Delay Analysis TechniquesDokument26 SeitenConstruction Delay Analysis Techniquesengmts1986Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hajj - Inner RealityDokument186 SeitenHajj - Inner RealityPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Presenting A ClaimDokument24 SeitenPresenting A ClaimKhaled AbdelbakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Is The Critical Path Not The Critical PathDokument9 SeitenWhen Is The Critical Path Not The Critical PathDWG8383Noch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Conditions Precedent in Building ContractsDokument5 SeitenEffects of Conditions Precedent in Building ContractsPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4Q 08 VariationDokument9 Seiten4Q 08 Variationqis_qistinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Construction Delay Analysis TechniquesDokument26 SeitenConstruction Delay Analysis Techniquesengmts1986Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2007 Aace - Earned ValueDokument11 Seiten2007 Aace - Earned ValuePameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basis of Schedule ArticleDokument5 SeitenBasis of Schedule ArticleAlex IskandarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Conditions Precedent To Recovery of Loss and ExpensesDokument9 SeitenConditions Precedent To Recovery of Loss and Expenseslengyianchua206Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2007 KC - Lessons From Wembly StadiumDokument3 Seiten2007 KC - Lessons From Wembly StadiumPameswaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- King BellDokument13 SeitenKing BellGovind Raj SutharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory in Search of Practice - The Right of Innocent Passage in THDokument48 SeitenTheory in Search of Practice - The Right of Innocent Passage in THWire WolfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advisory Opinion On The Use of Nuclear Weapon 1996Dokument1 SeiteAdvisory Opinion On The Use of Nuclear Weapon 1996alliqueminaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classification of Law PPT - PrintedDokument22 SeitenClassification of Law PPT - PrintedVANSHIKA CHAUDHARYNoch keine Bewertungen

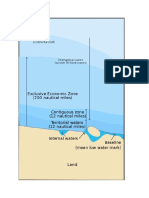

- UNCLOSDokument3 SeitenUNCLOSDiwakar Singh100% (1)

- International Law CSS LnotesDokument16 SeitenInternational Law CSS LnotesIsmail BarakzaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- HP Visa Restrictions Index 141101Dokument4 SeitenHP Visa Restrictions Index 141101HeartisteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 9 Civic Short NoteDokument23 SeitenGrade 9 Civic Short Noteynebeb zelalemNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Oci Sample FormDokument10 SeitenNew Oci Sample Formmegha patelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Untitled Bingo: B I N GDokument9 SeitenUntitled Bingo: B I N GFayna Pallares Freyer VNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964)Dokument22 SeitenBanco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964)Jumen Gamaru TamayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casesse - States - Rise - and - Decline - of - The - Primary - Subjects - of - The - International - Community PDFDokument15 SeitenCasesse - States - Rise - and - Decline - of - The - Primary - Subjects - of - The - International - Community PDFAntoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tzouvala - Capitalism As Civilisation - A History of International Law. 142-Cambridge University Press (2020)Dokument278 SeitenTzouvala - Capitalism As Civilisation - A History of International Law. 142-Cambridge University Press (2020)Catalina100% (1)

- Case Digest For Human Rights-2Dokument20 SeitenCase Digest For Human Rights-2ADNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domiciliary and Situs TheoryDokument1 SeiteDomiciliary and Situs TheoryJohn AlfredNoch keine Bewertungen

- State Responsibility: Serial No. Content Page NoDokument7 SeitenState Responsibility: Serial No. Content Page NoJishnu AdhikariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elelsharkawy Omar Raafat Mabrouk Emgs Approval LetterDokument1 SeiteElelsharkawy Omar Raafat Mabrouk Emgs Approval Letterapi-578454400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Peoples Union of Civil Liberties PUCL Vs Union of0114s970835COM194899Dokument14 SeitenPeoples Union of Civil Liberties PUCL Vs Union of0114s970835COM194899Tania Das KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Valles V Commission On Elections Facts:: ScedatDokument16 SeitenValles V Commission On Elections Facts:: ScedatJohn Lloyd MacuñatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application For National Visa (D-Visa) For Sweden: This Application Form Is FreeDokument2 SeitenApplication For National Visa (D-Visa) For Sweden: This Application Form Is FreeSudipta DuttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- United Nations Treaty Series: SyriaDokument3 SeitenUnited Nations Treaty Series: SyriadipublicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mdec Renewel LetterDokument2 SeitenMdec Renewel Lettersiti aishahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Visa Application Royal Norwegian Embassy DUF: Checklist - C Visa DateDokument2 SeitenVisa Application Royal Norwegian Embassy DUF: Checklist - C Visa DateYared GetachewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decline of The Optional Clause PDFDokument45 SeitenDecline of The Optional Clause PDFCristobal FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of Debrecen NewDokument57 SeitenUniversity of Debrecen Newnabaz rasoulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Police Character Certificate2Dokument1 SeitePolice Character Certificate2zohaibshabir25% (4)

- Korea Application FormDokument3 SeitenKorea Application FormMona Victoria B. PonsaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devolution of Powers in Switzerland and BelgiumDokument33 SeitenDevolution of Powers in Switzerland and BelgiumCentar za ustavne i upravne studijeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiplication of International Courts and Tribunals and Conflicting Jurisdiction - Problems and Possible SolutionsDokument2 SeitenMultiplication of International Courts and Tribunals and Conflicting Jurisdiction - Problems and Possible SolutionsMomal100% (1)

- CEDAW and IndiaDokument26 SeitenCEDAW and IndiaAkashNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaVon EverandFrom Cold War To Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin's RussiaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (23)

- Age of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentVon EverandAge of Revolutions: Progress and Backlash from 1600 to the PresentBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Hunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziVon EverandHunting Eichmann: How a Band of Survivors and a Young Spy Agency Chased Down the World's Most Notorious NaziBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (157)

- Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowVon EverandHeretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation NowBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (57)

- For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoVon EverandFor the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb, and the Murder That Shocked Jazz Age ChicagoBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (97)

- Kilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsVon EverandKilo: Inside the Deadliest Cocaine Cartels—From the Jungles to the StreetsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- The Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Von EverandThe Hundred Years' War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (127)