Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Inspiring Stories From Gandhiji

Hochgeladen von

Chaitali DesaiCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Inspiring Stories From Gandhiji

Hochgeladen von

Chaitali DesaiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

INSPIRING STORIES FROM GANDHIJI'S LIFE

Uma (For all ages) I The night was very dark and Mohan was frightened. He had always been afraid of ghosts. Whenever he was alone in the dark, he was afraid that a ghost lurking in some dark corner would suddenly spring on him. And tonight it was so dark that one could barely see one's own hand. Mohan had to go from one room to another. As he stepped out of the room, his feet seemed to turn to lead and his heart began to beat like a drum. Rambha, their old maidservant was standing by the door. "What's the matter, son?" she asked with a laugh. "I am frightened, child! Dai," Frightened Mohan of answered. what?" Shankar Joshi

"Frightened,

"See how dark it is! I'm afraid of ghosts!" Mohan whispered in a terrified voice. Rambha patted his head affectionately and said, "Whoever heard of anyone being afraid of dark! Listen to me: Think of Rama and no ghost will dare come near you. No one will touch a hair of your head. Rama will protect you." Rambha's words gave Mohan courage. Repeating the name of Rama, he left the room. And from that day, Mohan was never lonely or afraid. He believed that as long as Rama was with him, he was safe from the danger. This faith gave Gandhiji strength throughout his life, and even when he died the name of Rama was on his lips. III Mohan was very shy. As soon as the school bell rang, he collected his books and hurried home. Other boys chatted and stopped on the way; some to play, others to eat, but Mohan always went straight home. He was afraid that the boys might stop him and make fun of him. One day, the Inspector of Schools, Mr Giles, came to Mohan's school. He read out five English words to the class and asked the boys to write them down. Mohan wrote four words correctly, but he could not spell the fifth word `Kettle'. Seeing Mohan's hesitation, the teacher made a sign behind the Inspector's back that he should copy the word from his neighbour's slate. But Mohan ignored his signs. The other boys wrote all the five words correctly; Mohan wrote only four. After the Inspector left, the teacher scolded him. "I told you to copy from your neighbour," he

said angrily. "Couldn't you even do that correctly?" Every one laughed. As he went home that evening, Mohan was not unhappy. He knew he had done the right thing. What made him sad was that his teacher should have asked him to cheat. III In South Africa Gandhiji set up an ashram at Phoenix, where he started a school for children. Gandhiji had his own ideas about how children should be taught. He disliked the examination system. In his school he wanted to teach the boys true knowledgeknowledge that would improve both their minds and their hearts. Gandhiji had his own way of judging students. All the students in the class were asked the same question. But often Gandhiji praised the boy with low marks and scolded the one who had high marks. This puzzled the children. When questioned on this unusual practice, Gandhiji one day explained, "I am not trying to show that Shyam is cleverer than Ram. So I don't give marks on that basis. I want to see how far each boy has progressed, how much he has learnt. If a clever student competes with a stupid one and begins to think no end of himself, he is likely to grow dull. Sure of his own cleverness, he'll stop working. The boy who does his best and works hard will always do well and so I praise him." Gandhiji kept a close watch on the boys who did well. Were they still working hard? What would they learn if their high marks filled them with conceit? Gandhiji continually stressed this to his students. If a boy who was not very clever worked hard and did well, Gandhiji was full of praise for him. IV This incident occurred when Gandhiji was practising law in the city of Johannesburg in South Africa. His office was three miles from his house. One day a colleague of his, Mr Polak, asked Gandhiji's thirteen-year old son, Manilal to fetch a book from the office. But Manilal completely forgot till Mr Polak reminded him that evening. Gandhiji heard about it and sent for Manilal. He said, "Son, I know the night is dark and the way is long and lonely. You will have to walk nearly six miles but you gave your word to Mr Polak. You promised to fetch his book. Go and fetch it now." Ba and the family were upset when they heard of

Gandhiji's decision. The punishment seemed far too severe. Manilal was only a child, the night was dark and the way lonely. He had only forgotten a book after all. It could be brought the next day. This was what they all felt, but no one had the courage to say anything. They knew that once Gandhiji's mind was made up, nobody could change it. At last Kalyan Bhai plucked up courage. "I'll fetch the book," he offered. Gandhiji was gentle but firm, "But the promise was made by Manilal." "Very well, Manilal will go but let me go with him," Kalyan Bhai pleaded. Gandhiji agreed to this and Manilal set off with Kalyan Bhai to fetch the book. The kind and gentle Gandhiji could be firm as a rock at times. He saw that Manilal kept his word and did as he had promised. V Soon after Gandhiji's return from South Africa, a meeting of the Congress was held in Bombay. Kaka Saheb Kalelkar went there to help. One day Kaka Saheb found Gandhiji anxiously searching around his desk. "What's the matter? What are you looking for?" Kaka Saheb asked. "I've lost my pencil," Gandhiji answered. "It was only so big." Kaka Saheb was upset to see Gandhiji wasting time and worrying about a little pencil. He took out his pencil and offered it to him. "No, no, I want my own little pencil," Gandhiji waste insisted time like looking a for stubborn it child. now." "Well, use it for the time being," said Kaka Saheb. "I'll find your pencil later. Don't "You don't understand. That little pencil is very precious to me," Gandhiji insisted. "Natesan's little son gave it to me in Madras. He gave it with so much love and affection. I cannot bear to lose it." Kaka Saheb didn't argue any more. He joined Gandhiji in the search. At last they found it-a tiny piece, barely two inches long. But Gandhiji was delighted to get it back. To him it was no ordinary pencil. It was the token of a child's love and to Gandhiji a child's love was very precious. VI Children loved visiting Gandhiji. A little boy who was there one day, was greatly distressed to see the way Gandhiji was dressed. Such a great man yet he doesn't even wear a shirt, he wondered. "Why don't you wear a kurta, Gandhiji?" the little boy couldn't help asking finally. "Where's the money, son?" Gandhiji asked gently. "I am very poor. I can't afford a kurta." The boy's heart was filled with pity. "My mother sews well", he said. "She makes all my clothes. I'll ask her to sew a Kurta for you." "How many Kurtas can your mother make?" Gandhiji asked. "How many do you need?" asked the boy. "One, two, three.... she'll make as many as you want." Gandhiji thought for a moment. Then he said, "But I am not alone, son. It

wouldn't be right for me to be the only one to wear a kurta." "How many Kurtas do you need?" the boy persisted. "I'll ask my mother to make as many as you want. Just tell me how many you need." "I have a very large family, son. I have forty crore brothers and sisters," Gandhiji explained. "Till every one of them has a kurta, how can I wear one? Tell me, can your mother make kurtas for all of them? At this question the boy became very thoughtful. Forty crore brothers and sisters! Gandhiji was right. Till every one of them had a kurta to wear how could he wear one himself? After all the whole nation was Gandhiji's family, and he was the head of that family. He was their friend, their companion. What use would one kurta be to him? VII One day Gandhiji and Vallabhbhai Patel were talking in the Yaravada jail when Gandhiji remarked, "At times even a dead snake can be of use." And he related the following story to illustrate his point: Once a snake entered the house of an old woman. The old woman was frightened and cried out for help. Hearing her, the neighbours rushed up and killed the snake. Then they returned to their homes. Instead of throwing the dead snake far away, the old woman flung it onto her roof. Sometime later a kite flying overhead spotted the dead snake. In its beak the kite had a pearl necklace which it had picked up from somewhere. It dropped the necklace and flew away with the dead snake. When the old woman saw a bright, shining object on her roof she pulled it down with a pole. Finding that it was a pearl necklace she danced with joy! When Gandhiji finished his story, Vallabhbhai Patel said he too had a story to tell: One day a bania found a snake in his house. He couldn't find anyone to kill it for him and hadn't the courage to kill it himself. Besides, he hated killing any living creature. So he covered the snake with a pot and left it there. As luck would have it, that night some thieves broke into the bania's house. They entered the kitchen and saw the overturned pot. "Ah," they thought, "the bania has hidden something valuable here." As they lifted the pot, the snake struck. Having come with the object of stealing, they barely left with their lives. VIII Gandhiji went from city to city, village to village collecting funds for the Charkha Sangh. During one of his tours he addressed a meeting in Orissa. After his speech a poor old woman got up. She was bent with age, her hair

was grey and her clothes were in tatters. The volunteers tried to stop her, but she fought her way to the place where Gandhiji was sitting. "I must see him," she insisted and going up to Gandhiji touched his feet. Then from the folds of her sari she brought out a copper coin and placed it at his feet. Gandhiji picked up the copper coin and put it away carefully. The Charkha Sangh funds were under the charge of Jamnalal Bajaj. He asked Gandhiji for the coin but Gandhiji refused. "I keep cheques worth thousands of rupees for the Charkha Sangh," Jamnalal Bajaj said laughingly "yet you won't trust me with a copper coin." "This copper coin is worth much more than those thousands," Gandhiji said. "If a man has several lakhs and he gives away a thousand or two, it doesn't mean much. But this coin was perhaps all that the poor woman possessed. She gave me all she had. That was very generous of her. What a great sacrifice she made. That is why I value this copper coin more than a crore of rupees." IX This incident occurred in Noakhali. After the Hindu-Muslim riots Gandhiji toured the area on foot to reassure and comfort the people. He would set off from a village soon after dawn and arrive at the next village after sunset. On arrival he would first attend to his work then he would take a bath. Gandhiji used a rough stone to clean his feet. Miraben had given this stone to him many years ago and Gandhiji had kept it carefully ever since. He took it with him everywhere. One evening after they had arrived at a village and Manu was getting Gandhiji's bath ready, she noticed that the stone was missing. She looked everywhere but could not find it. She told Gandhiji that the stone was lost and added, "It must have been left behind at the weaver's where we stayed yesterday. What should I do now?" Gandhiji thought for a moment. Then he said, "Go and fetch the stone. If you suffer once, you'll not forget another time." "Can I take someone with me?" Manu asked. "Why?" questioned Gandhiji. Manu was silent. She did not want to admit that she was frightened to go alone. The road to the village lay through forests of betelnut and coconut and it was easy to lose one's way. Besides, Manu was barely sixteen years old and she had never gone anywhere alone. But she could not think of an answer. So Manu took the path they had taken earlier in the day. Carefully following the old footprints she managed to reach the village and find the weaver's house. The old woman who lived there recognised her and welcomed her warmly. Tired and rather irritated Manu told her why she had come. But how was the old woman to have known that that bit of stone was so valuable? She had thrown it

away with the rubbish. They both began to search for it. At last much to Manu's joy they found it. Many had left the house at 7.30 in the morning. By the time she returned it was past one in the afternoon. She had walked nearly fifteen miles. Worn out, hungry and irritated she went straight to Gandhiji and put the stone in the lap. Then she burst into tears. "This stone was a real test for you," Gandhiji told her gently. "Do you know that this stone has been with me for the last twenty-five years. It has gone with me everywhere, from jails to mansions. I can easily get another stone like it, but I wanted you to learn that it is bad to be careless." "I've never prayed as hard as I did today," said Manu. "I want to make women brave and fearless", Gandhiji said. "Today not only you but I too learnt a lesson." Manu did not say anything but she must have thought Gandhiji's methods were very unusual. MAHATMA GANDHI -By (For 5 to 7 Year Old Children) :1: Children, there is not a single country in the whole world where the name of Mahatma Gandhi is not known. Do you know why Gandhiji became so famous? It was because he dedicated his whole life to the service of the motherland, and service of humanity. Today, I am going to tell you in brief, the story of Mahatma Gandhi, the father of the Nation, or Bapuji, as he is affectionately called. In the early days our country was made up of a large number of small Princely Kingdoms. Porbandar in Gujarat was one such Princely Kingdom. Gandhiji's father Karamchand Gandhi, popularly known as Kaba, was a Minister there. Kaba Gandhi was an honest, upright man, a strict disciplinarian, and very hot tempered. His wife Putlibai was a extremely religious person. She would not have her meal until she had worshipped the sun. Hence sometimes in the rainy season, she would go hungry for two-three days at a stretch. She was a very loving person, and immensely hard-working. To these parents a son was born on October 2nd, 1869. He was their youngest son. He was called Mohandas. He was our Gandhiji. The strict discipline of his father, the religious bent of mind of his mother, all influenced Gandhiji greatly. He was deeply attached to his parents and brothers. The values of truthfulness, honesty, integrity were instilled in him from the very beginning. As a child he was not very brave. He was mortally afraid of the dark, of ghosts and spirits, and also of snakes and scorpions. At night he would cry in fear. The maid who looked after him scolded him very often. "You should be ashamed of yourself" she would say. "What will you do when you grow up?" She then told him that everytime he was frightened he should take the name of God Rama. Gandhiji took her advice, and gradually he overcome his fear. Soon it was time for him to go to school. As his father was in Rajkot at that time, he attended the school there. Being extremely shy, he did not mix with the other children. Most of the time he kept to himself. In the beginning he did not like some of the subjects that were taught to him, but with encouragement from his teachers he studied them, and Jyoti Solapurkar

began to enjoy them. From then onwards he took his studies very seriously. Mohan was very shy. As soon as the school bell rang, he collected his books and hurried home. Other boys chatted and stopped on the way; some to play, others to eat, but Mohan always went straight home. He was afraid that the boys might stop him and make fun of him. One day, the Inspector of Schools, Mr Giles, came to Mohan's school. He read out five English words to the class and asked the boys to write them down. Mohan wrote four words correctly, but he could not spell the fifth word `Kettle'. Seeing Mohan's hesitation, the teacher made a sign behind the Inspector's back that he should copy the word from his neighbour's slate. But Mohan ignored his signs. The other boys wrote all the five words correctly; Mohan wrote only four. After the Inspector left, the teacher scolded him. "I told you to copy from your neighbour," he said angrily. "Couldn't you even do that correctly?" Every one laughed. As he went home that evening, Mohan was not unhappy. He knew he had done the right thing. What made him sad was that his teacher should have asked him to cheat. As was the custom in those days, when he was about 13-14 years old, he got married. His wife's name was Kasturba (and she was as old as him). It was at this time that Gandhiji fell into bad company and picked up many bad habits. It was because of these bad habits, that unknown to his parents, he was once forced to sell a part of his gold bracelet. However, he soon realised his mistake, and amply repented his sinful behaviour. He decided to make a clean breast of everything to his father, but he lacked the courage to face him. So instead, he wrote a letter to his father, mentioning all the sinful deeds he had done. He gave the letter to his father, and stood by his bedside, his face hanging down in shame. At that time Kaba Gandhi was seriously ill. He felt misreable when he read the letter. Tears rolled down his cheeks, but he did not say a single word to his son. It was too much for Gandhiji to bear. Right then he resolved that he would always lead a truthful and honest life, and throughout his life he stuck to his resolution. :2: During his father's illness Gandhiji nursed him with great devotion and care, but unfortunately his father never recovered from his illness. He died soon thereafter. In 1887, two years after his father's death, Gandhiji passed his High School examination. At that time he was 18 years old. Everyone in the family decided that he should go to England and become a Barrister, so that on his return he could become a Dewan like his father. Respecting their wishes, Gandhiji set sail for England in 1888. Life was entirely different in England. The style of dressing, eating habits, everything was all new to him. He was totally confused and bewildered for some time. However, he soon got adjusted to the new environment. He had promised his mother that he would not eat non-vegetarian food, or drink alcohol, and he remained true to his word. Many attempts were made to make Gandhiji accept Christianity as his religion. Gandhiji remained firm. However, he studied the Bible, Geeta and Quran and came to the conclusion that the principle tenets in all religions are the same. So whether the person was Hindu, Muslim or Christian, Gandhiji felt that as long as he followed the religion principles, he attained salvation. He told this to all those who had tried to convert him, and remained a staunch Hindu till the very end. Gandhiji concentrated on his studies thereafter, and successfully passed his Bar examination. He returned to India in 1891, after the completion of his studies. Eagerly he looked forward to meeting his mother, and giving her the good news, but he was to be sorely disappointed. For while he was away in England, his mother had passed away. The news of her death had been withheld from him because his brother thought he would be mentally disturbed, and

his studies would be affected. *** :3: After qualifying as a Barrister, he set up his practice as a lawyer, in Rajkot. As he did not get much work there, he came to Bombay. Even in Bombay he did not get any cases. Finally, he got one case. He prepared well for it, but in court he was unable to present it satisfactorily. Disappointed, he felt he would never make a successful lawyer. Just at that time Gandhiji's elder brother managed to get him a case. He was asked to represent Mr. Abdulla, a rich businessman in South Africa. After much deliberation, Gandhiji agreed to accept the case. He left his homeland and set sail for Africa in 1895. Although there were many Indians staying in Africa at that time, all the power was in the hands of the British people. They considered themselves superior, and treated the Indians and the natives in a most insulting manner. Gandhiji undertook Abdulla's case and handled it very well. The Indians were very much impressed, and wanted Gandhiji to stay on in Africa. In connection with his work, Gandhiji travelled a good deal. However, he was treated very badly by the British people. Wherever he went, he had to face insults and rudeness. At times, he was even physically assaulted. One day, when he was travelling from Durban to Pretoria in the first class compartment of a train, a Britishman boarded the compartment. On seeing Gandhiji, the Britishman got furious. He called the Railway officer, and both ordered him to get out of the train. Since Gandhiji had purchased a first class ticket, he refused to do so. However, they paid no heed to him. Gandhiji also did not budge. Finally the police were summoned. They pushed him out of the compartment and threw his luggage out of the window. Gandhiji had to spend the whole night on the platform. This was only one of the many humiliating experiences Gandhiji had to face. He had decided to return to India on the completion of his work in Africa, but the plight of the Indians there disturbed him greatly. He resolved to stay, and fight the unjust and inhuman laws that were imposed on them. For everywhere there was discrimination. There was one set of rules for the Indians and natives, and a different set for the British people. *** :4: Gandhiji gave considerable thought to the matter. He realised that to fight against injustice it was vital for the people to have unity amongst themselves. He tried very hard to bring about this unity. He organised many meetings, and made the people aware of the situation. In reply, the people appointed him as their leader, and agreed to be guided by him. Since all the power was in the hands of the English people, Gandhiji realised that to fight them it was necessary to use an entirely different method. It was then that he thought of the novel idea of `Satyagraha'. Satyagraha insistance on truth, a non violent protest against injustice. His movement aimed at fighting the many unjust laws that were imposed on them, and for it to be successful, he was prepared to face all hardships and obstacles. It was no easy task. He suffered much humiliation, faced many problems, but he did not give up. It was during this time that a war broke out between the British and the Dutch settlers in Africa. It was known as the Boer War. Gandhiji and other Indians

gave whatever help they could to the British. The British won the war, and taking into consideration the help Gandhiji had rendered to them, they gave the Indians more privileges. They also agreed to abolish the unjust laws that were imposed on them. Gandhiji felt very happy that his stay in Africa had served some useful purpose. Thinking that his work was now over, he decided to return to his motherland. The people were very reluctant to let him go back. They were very keen that he should settle down in Africa itself. Finally Gandhiji told them that he would go to India, but come to Africa whenever they called him. Only then did the people agree to let him go. They gave him a grand farewell, and showed him with many expensive gifts. However Gandhiji did not accept anything. He donated everything to the local organisations. During his long stay in Africa, Gandhiji visited India sometimes, where he met many important leaders and sought their advice. Gopal Krishna Gokhale was one such leader who rendered assistance to Gandhiji in many ways. Gandhiji admired him tremendously, and looked upon him as his mentor. It was largely due to him that Gandhiji joined the mainstream of Indian politics. :5: By the time all these developments took place in Africa, it was 1914. Gandhiji had spent almost 20 years in that country. He returned to India, for he had made up his mind to fight for the freedom of India. He decided that he would not miss a single opportunity that would help him in serving his country and countrymen. As such he toured the whole of India, and brought an awakening in the people living in villages and towns. North of the Ganges, near the boundary of Nepal, was a small place called Champaranya. It was noted for its cultivation of Indigo dye. Unfortunately, the British planters in Champaranya treated the local workers most cruelly. Worse still, the Government paid little heed to the workers cries. With the result that they were utterly disgusted with their employers. Gandhiji heard of this and went to Champaranya to do something for them. He was unable to bear their miserable plight. He began a satyagraha against the injustice done to the workers. Finally the British were compelled to stop their inhuman treatment of the workers. This satyagraha came to be known as the `Champaranya Satyagraha'. After the success of the `Champaranya Satyagraha', Gandhiji felt that he should settle down in one place. He selected a site near the banks of the Sabarmati river in Gujarat, and established his Ashram there. He decided that thereafter he would devote all his time to the service of humanity, and work for the downtrodden. He preached what he practiced. He picked up the cause of the Harijans who were treated most atrociously all over the country. He raised his voice against the inhuman and unjust treatment meted out to them. He started two newspapers `Harijan' and `Young India', and through them he expressed his views and spread social awareness in the people. :6: In the meantime all over India agitations and uprisings against the British rule where on the increase. In 1920, Lokmanya Tilak died, and Gandhiji became the

leader of the Freedom Movement. Under his guidance, the people went on Satyagraha to fight against injustice. He was arrested and imprisoned many times, but that did not deter him and his loyal followers. They continued their fight for freedom with even greater fervour. Gandhiji was greatly respected for his simple living, high thinking, and fearless attitude. The British too were greatly impressed by him, and called him for negotiations regarding India's freedom. Since it had been decided that the freedom struggle would not stop until full freedom was granted, the negotiations did not serve any purpose. Various forms of Satyagraha and Civil Disobedience movements took place at that time. The `Swadeshi Movement' (to use local made goods) was one of them. Gandhiji advised and encouraged the people to use Indian goods and use Khadi (hand spun cloth). He himself wore Khadi clothes, and would sit to spin on his Charkha (Spinning wheel). People stopped buying British made goods. Instead, they lit bornfires of these goods. The Government, with the help of the police and the army, tried its best to put an end to all these demonstrations and agitations, but these were unsuccessful. On the contrary, they became more intense. The Government had imposed a tax on salt, and Gandhiji started the `Salt Satyagraha'. He and many other leaders were imprisoned, but the struggle for freedom continued with greater intensity. While India fought for freedom, in Europe, the second world war had begun. The British looked towards India for help, but Gandhiji started the Non-co-operation Movement. Jawaharlal Nehru and many other Indian leaders joined the movement because they all had immense faith in Gandhiji. The British Government thought it would please the Indians by granting them partial freedom. Once again they began negotiations with Gandhiji, but Gandhiji made it clear that he and his people wanted nothing less than complete freedom (Independence). To make this demand stronger, the Indian National Congress passed the Quit India resolution in 1942, wherein they demanded that the British leave India immediately. Angered by this resolution, the British again imprisoned him and his wife Kasturba. Kasturba died in jail. She was always behind him in his freedom movements and the other leaders. Many secret organisations were formed as a result, and they put a number of obstacles in the regular functioning of the Government. Around this time Netaji Subhashchandra Bose formed his `Azad Hind Fauj' in Japan. Many Indians who were in the British Army, left it and joined the Indian Netaji's Army. The British Government realised that it was now impossible for them to continue their rule in India, They released Gandhiji and other leaders from prison, and once again began negotiations with him. Finally, on 15th August 1947, India attained freedom, and for the first time the Indian tri-colour National flag fluttered on the Red Fort in Delhi. However, in its fight for freedom, India had to pay a heavy price. What was once a large single geographical unit, now comprised of two new nations - India and Pakistan. It was during this period that Hindu Muslim riots took place all over the country. People of both communities were killed brutally, and there was large scale bloodshed all around. Gandhiji put his life in danger, pleaded with the people and made ceaseless efforts to stop this senseless killing. After Independence, Gandhiji concentrated his attention on the betterment of the Downtrodden people. He went from village to village and advised the people that for the good of the country it was necessary for everyone to work together in unity and harmony. Equal opportunities and equal status was what he wanted. Although Gandhiji strived so hard for unity, there were some people who were under the misconception that Gandhiji favoured the Muslims. On 30th January 1948, in Delhi, when Gandhiji set out to attend a prayer meeting, he was shot dead by an assailant. His last words were `Hey Ram'. People all over the world paid rich tribute to Gandhiji. The great Mahatma's life had come to an end! The news shocked everyone. Not only India, but the whole world mourned the

death of the great man a real Mahatma, who had dedicated his entire life to the service of humanity, and had taught the importance of truth, brotherhood, peace, non-violence, equality and simplicity. The most befitting tribute that we can pay him, is to follow the path he has shown us. All for a Stone Many people know that instead of soap, Gandhiji used a stone to scrub himself. Very few people, however, know how precious this stone, given by Miraben, was to Gandhiji. This happened during the Noakhali march, when Gandhiji and others halted at a village called Narayanpur. During the march, the responsibility of looking after this particular stone, along with other things, lay with Manuben. Unfortunately, though, she forgot the stone at the last halting place. "I want you to go back and look for the stone," said Bapu. "Only then will you not forget it the next time." "May I take a volunteer with me?" "Why?" Poor Manu. She did not have the courage to say that the way back lay through forests of coconut and supari, (betel nut) so dense that a stranger might easily lose his way. Moreover, it was the time of riots. How could she go back alone? But go she did, and alone; after all she had committed the error. Leaving Narayanpur at 9:30 in the morning, Manu trudged along the forest path, taking the name of Ram as she went. On reaching the village she went straight to the weaver's house that had been their last halt. An old woman lived there. And she had thrown the stone away. When Manuben found it after a difficult search her joy knew no bounds. Carrying the precious stone, she returned to Narayanpur by late afternoon. Placing it in Bapu's lap she burst into tears. "You have no idea how happy I feel. This stone has been my cherished companion for the past twenty-five years. Whether in prison or in a palace it has been with me. Had it been lost it would have distressed me and Miraben as well. Now, you have seen that every useful thing is worth taking care of, even a stone." Manuben said, "Bapu, if ever I took Ramanaam with all my heart it was today." Bapu laughed and replied, "Oh yes, one remembers the Lord only when one is in trouble." A Car and a Pair of Binoculars

Here's how a close friend of Gandhiji came to give up two of his possessions. This friend, a German named Kallenbach, was an engineer-architect whose earnings had made him rich. Kallenbach shared the beliefs and principles of Gandhiji and worked closely with him in the struggle against the white South African government. This, however, was not always easy. It was 1908. Gandhiji was being released from jail, having served his sentence for the Satyagraha struggle. At the gate he realised that his friend Kallenbach was so happy at his release that he had actually bought a new car to take him home. Gandhiji refused to enter the car. "It is stupid to spend so much money on a car when other people are suffering. You must return it to the seller before doing anything else." On another occasion, Kallenbach and Gandhiji were returning to South Africa from England by ship. Kallenbach had a well-crafted and expensive pair of binoculars. This led to a serious discussion. What exactly is essential for a good and simple life? And if non-essentials are not required, shouldn't they be discarded? The binoculars were costly, but not essential. Persuaded by Gandhiji, Kallenbach threw them into the sea. And felt greatly relieved. K. S. Narayanaswamy My Master's Master Gandhiji inspired many, but who inspired him? Here's a story that gives hint towards this. This story has to do with Dr. Kumarappa, who had decided to live in a hut in Kallupatti in Madurai District of Tamil Nadu. It was a hut he had built himself. On the inner walls of his hut hung a photograph that would attract anyone's attention. It was a picture that showed a common farmer, with a turban on his head. What was this photograph doing here, in the house of a man such as Dr. Kumarappa? Many an important visitor would ask Dr. Kumarappa about this mysteriously unimportant looking man. "Oh, he's my master's master." Dr. Kumarappa would say. "Master's master?" "You see," Dr. Kumarappa would explain to the puzzled visitor, "my master is Gandhiji, and this villager, indeed every poor person in the land, is his master." Enter the Monkeys Of course you've heard of the three monkeys that are always mentioned along with Gandhi's name. But have you also heard of how they came to be with him in the first place? Find out from this recollection by someone who worked with both Tagore and Gandhi. Most of the people who came to see Gandhi sought his advice on something or the other. But one day came a party of visitors from China. "Gandhiji, we have brought you a small gift," they said. "It is no bigger than a child's toy, but it is famous in our country." To Gandhi's delight it was a set of the three monkeys that were later to

become so well-known and to be kept carefully by him for the rest of his life. (Majorie Sykes was born in 1905, and obtained a Teacher's Diploma from Cambridge in 1927. She came to India to teach at Madras, then went on to Shantiniketan during 1938-47. She came to Sevagram in 1948 to work in the Nai Talim School. Later she worked at Hoshangabad. She passed away in April 1996 in England.) Premchand Quits his Job Did you know that, inspired by the Non-cooperation Movement, the Hindi writer Premchand decided to give up his job? But it wasn't such an easy decision. Here's how it happened, narrated by his wife. It was 1920. Non-cooperation was in the air. Gandhiji came to Gorakhpur. He (Premchand, that is) was ill. Even then, our two sons, Babuji and I went to the meeting. Both of us were deeply affected by Mahatmaji's speech. Of course there was illness. There were compulsions. But from that very time he lost interest in continuing in his government job. When he had recovered from his long illness he said to me one day, "If you agree I will leave this government job." I asked for two to three days time to think it over. We had thought that he would become a professor, that our days would pass in comfort. More so, because his health had not been very good. And now this idea of simply letting go whatever had been attained. At that time he got an overall amount of around Rs. 125. And because he taught in a school, he also got time at home. I kept thinking: what will we do once he gives up his service. Looking at our needs, his prolonged illness, the fact that we had no house of our own, all this made me feel like telling him not to resign. Four to five days later he asked me what I had decided. I thought, now that he is better, I will not worry about his giving up the job. In just those days, too, everyone was seething with anger at the gruesome massacre at Jallianwala Bagh. Perhaps I was too. By the next day I had braced myself to face all those difficulties which were bound to come in the wake of his resignation. I said to him, "Give up the job." I had thought it would be painful leaving a job he had had for twenty-five years. But no, compared to the oppression being wreaked on the country, it was almost no pain at all. Returning his Medals In South Africa, Gandhi had worked shoulder to shoulder with the British on occasions and even received awards for this. However, as soon as he felt he could no longer accept the British government, he returned the awards bestowed upon him. This was how his letter to the Viceroy ran, quoted from Young India dated 4th August, 1920:

It is not without a pang that 1 return the Kaisar-i-Hind gold medal granted to me by your predecessor for my humanitarian work in South Africa, the Zulu War medal granted in South Africa for my services as officer in charge of the Indian volunteer ambulance corps in 1906 and the Boer War medal for my services as assistant superintendent of the Indian volunteer stretcher-bearer corps during the Boer War of 1899-1900. I venture to return these medals in pursuance of the scheme of noncooperation inaugurated today in connection with the Khilafat movement. Valuable as these honours have been to me, I cannot wear them with an easy conscience so long as my Mussalman countrymen have to labour under a wrong done to their religious sentiment. Events that have happened during the past one month have confirmed me in the opinion that the Imperial Government have acted in the Khilafat matter in an unscrupulous, immoral and unjust manner and have been moving from wrong to wrong in order to defend their immorality. I can retain neither respect nor affection for such a Government. Boer and Zulu Wars Like the British Boers were white Europeans who had settled in south Africa. the Boers had come from Holland. In his autobiography, Gandhi writes thus on this war: When the war was declared, my personal sympathies were all with the Boers, but my loyalty to the British rule drove me to participation with the British in that war. I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty, as such to participate in the defence of the British Empire. so I collected together as many comrades as possible, and with very great difficulty got their services accepted as an ambulance corps. In 1906, the Zulu Rebellion broke out in Natal. This was actually a campaign against tax being imposed by the British on the Zulus, who were demanding their rights in their own land. However, the whites declared war against the Zulus. Again, Gandhi's sympathies with the Zulus but he considered it his duty to help the British and he volunteered to form an Indian Ambulance Corps. This Corps had twenty-four men, and was in active service for six weeks, nursing and looking after the wounded. Basic Pen Most people have lost a pen at some time or the other. So did Gandhi. He had a costly fountain pen which was pilfered. The pen was immediately replaced but the theft pained him. Henceforth, he decided, he would not use anything so attractive that it would tempt someone to steal it. He began using a pen-holder and a nib. (Do you know what this was like? Ask your parents if YOU don't.) But even this did not last forever. For the nib once got bent and he had to send Manubehn to get a new one. This was a loss of time when every moment was precious. Even a few minutes' delay could upset a whole day's schedule. When Manubehn returned, she found Bapu sharpening the other end of the wooden holder. "Why"' she wanted to know.

At which Gandhi said, "Now the point of my nib will never get curved. In olden days, people used such kittas for writing purposes. Using them made the handwriting better, and they did not cost a paisa." So he now had a pen that would neither be stolen or spoilt. And do you know to whom the first letter to be penned with this kitta was addressed--Lord Mountbatten. Prisoner No. 1739 When Gandhi was a prisoner of the South African Government in November 1913 in Bloemfontein Gaol, his jail card bore the following among other details: No. : 1739 Name : Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi Religion : Hindu Age : 43 Trade : Solicitor Date of Sentence : 11-11-13 Date of Discharge : 10-11-14 Sentenced : Pounds 20 or 30 months (on each of four counts). Gandhiji was awarded 50 marks for good conduct. As he did not pay the fine, he had to serve the full sentence. The card bears his thumb impressions. About the prison diet supplied to him the card says: "Allowed vegetable diet owing to religious scruples. Diet : 12 bananas, 12 dates, 3 tomatoes and 1 lemon each, 2 ounces of olive oil, and 3 selected groundnuts." Gandhi's White Brother In the vegetarian restaurant where he took his food, Kallenbach would often see a young barrister. This was an Indian lawyer who dressed like an Englishman and had taken up the cause of Indian labourers in South Africa. It was not long before the German engineer and M. K. Gandhi became friends. They had a great deal in common a deep attraction for simple life and working for the good of their fellow beings. At the time Gandhi was struggling for the rights of Indians and Africans in a land dominated by white men. The form of resistance that Gandhiji used was unique: satyagraha. He would patiently appeal to the good sense of the whites while also refusing to follow their laws that he regarded evil. He was willing to suffer punishment for breaking these laws but refused to hate the white men.

Kallenbach was attracted by this method. He and Gandhiji worked together for the poorest of the poor. They changed their own life style and honoured every useful work. They said that a lawyer or an engineer was not superior to a cobbler or a scavenger. In fact they went to a Chinese cobbler in Johannesburg and learnt to make footwear. And they undertook to clean their own latrines, something most people would not do in these days. From Ruskin's book Unto This Last, Kallenbach and Gandhi laid down three principles for themselves: (i) the good of the individual is in the good of all; (ii) all work is noble and all are equal; and (iii) a life of labour is worth living. In 1903 Gandhi's family came over to South Africa. Though Kallenbach became a dear uncle to his three children, Gandhi would not let him buy costly toys for them. They must not feel that they are different from poor people, he would say. In 1910 Kallenbach, who was a rich man, donated to Gandhi a thousand acre farm belonging to him near Johannesburg. This was a very great gift indeed and was used to run Gandhi's famous 'Tolstoy Farm' that housed the families of satyagrahis. With the satyagraha campaign in full swing, Gandhi would often go to prison. During such times, Kallenbach would take up the work of editing Indian Opinion, a weekly paper started by Gandhi. Being white, he could not be punished under the South African laws. This angered the white rulers no end, but Kallenbach carried on as a co-worker with Gandhi. When Gandhi started the Phoenix Ashram near Durban, living as a farmer and labourer, Kallenbach gladly joined in this new life. He built the simple sheds for the inmates, working as a mason and carpenter. In 1915 Gandhi returned to India. The First World War had broken out. England and Germany were at war with each other. Being a German, Kallenbach was refused entry into India and had to return sadly to South Africa, where he continued his work as a satyagrahi. Kallenbach did come to India in 1936, when he visited Gandhi's ashram at Sevagram near Wardha. He was ill at that time. Gandhi nursed him back to health himself. In 1937 the Second World War broke out, Kallenbach was again put into jail by the South African Government. When Kallenbach died of illness a little after this, in 1938, Gandhiji felt he had indeed lost a brother. Who Saw Gandhi? Sometimes old words acquire new meanings, as happened in this incident. Gandhi had arrived at the Harijan Ashram in Delhi. In this ashram ran a workshop to train boys in various vocational skills.

When Gandhi entered this workshop during his round of inspection, the boys working there stopped what they were doing to stare at him curiously. A lone boy, engrossed in making rotis, was so involved in cooking them over the chulha that he did not get to know that Gandhi had just passed from there. As Gandhi came out of the workshop, one of the boys remarked in amazement, "Arrey, the boy making rotis did not see Bapu at all." Bapu responded at once, saying, "If there is anyone who really saw me at all in the whole workshop, it is the boy who was making rotis." An Early School What were schools like a hundred and ten years ago when Gandhi was a child? The Kattyawar High School, Rajkot where Gandhi studied for seven years, was the ninth English school started in Bombay Presidency (find out from your elders what this was) and the first in Kathiawar (now Saurashtra). It had a good building with classrooms that had benches to sit on and desks at which to write (unlike most other schools of the time). Inside the class-room, the teacher had his seat on a raised dais (or platform) facing the boys. Girls did not attend this School. (In fact, there weren't many schools where girls could study.) At the age of 11 years, 2 months and 2 days, the young Mohandas was enrolled in standard l-B. The school's fee for standard I was 8 annas (50 paise) a month. On week days the school worked from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., with a recess of an hour at 23. On Saturdays it worked for half an hour less. The subjects Gandhi had to study in standard I were arithmetic, Gujarati, history and geography. In geography, in fact, his marks in the first terminal examination of standard I were: zero. In English dictation that is, spelling too, he got no marks at all. In the same exam his rank was 32nd among the 34 students of his division. At the annual exam, though, he was able to secure the sixth rank among pupils in both divisions. An Unusual March It was a celebration of sorts. No mithai (sweets) or diyas (lamps) or even flowers. Instead, a march. To observe a hundred and twenty fifth anniversary. This was a march to commemorate Mahatma Gandhi's 125th birthday. And this time it was not at Sabarmati or Porbandar but in England-the very place and the same people against whom he had. The march took place between Birmingham and London, a distance of 125 miles, and lasted from the 22nd of September to the 2nd of October, 1994. At every step, English men and women joined the march, lending support wherever they could. Sometimes, between one halt and another, there would be no place where we could eat. Village folk would then pitch in with boiled potatoes and

tomatoes to keep the march going. Along the way, one of the Indian marchers lost his camera. Later, when he returned home after the march, he was delighted to receive the news that his camera had been found and an English lady was taking the trouble to send it back to him. Prof. Ramjee singh

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Short Stories CollectionDokument39 SeitenShort Stories Collectionsarita panigrahi0% (1)

- A Cosmic Event of Mystic SignificanceDokument50 SeitenA Cosmic Event of Mystic Significance7h09800hNoch keine Bewertungen

- Astrology Print OutDokument22 SeitenAstrology Print OutNaresh BhairavNoch keine Bewertungen

- C. J. Van Vliet - The Coiled Serpent (1939)Dokument470 SeitenC. J. Van Vliet - The Coiled Serpent (1939)muruganaviator100% (1)

- MagusDokument137 SeitenMagusKCarlson1292Noch keine Bewertungen

- CBR Stories From AfricaDokument71 SeitenCBR Stories From AfricaOlmedo Zambrano Cordovez100% (1)

- Mozart SongsDokument6 SeitenMozart Songscostin_soare_2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Booklet 2020 Final PDFDokument44 SeitenBooklet 2020 Final PDFElvie CalledoNoch keine Bewertungen

- StoriesDokument42 SeitenStoriesjuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short StoriesDokument17 SeitenShort StoriesShubham PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal On Islamic Banking 2.Dokument18 SeitenResearch Proposal On Islamic Banking 2.Peter Phillemon75% (8)

- Decolonising The Mind ThiongoDokument5 SeitenDecolonising The Mind ThiongoChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nasreddin: The World Is Going To End TodayDokument10 SeitenNasreddin: The World Is Going To End TodayFebrianto PatabangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kids Play Mahatma GandhiJiDokument10 SeitenKids Play Mahatma GandhiJiGarima Tiwari80% (20)

- A Priori Foundations of Civil LayDokument135 SeitenA Priori Foundations of Civil LayapplicativeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adaptations For Hunting: Flight and FeathersDokument4 SeitenAdaptations For Hunting: Flight and FeathersanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ramna AmDokument81 SeitenRamna AmoshothesecretNoch keine Bewertungen

- All The Ten Stories FinalDokument56 SeitenAll The Ten Stories FinalKaramchedu Vignani VijayagopalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Writing DramaDokument4 SeitenTeaching Writing DramaGold RegalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZGÂRCITULDokument8 SeitenZGÂRCITULAdriana EneNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Autobiography of a 25-year-old: From Prison to Seoul National UniversityVon EverandThe Autobiography of a 25-year-old: From Prison to Seoul National UniversityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spoken English 25 Short StoriesDokument22 SeitenSpoken English 25 Short StoriesAaftabkhan Khanaaftab08Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mothers DayDokument41 SeitenMothers DaymsooflooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short StoryDokument9 SeitenShort Storyapi-276899431Noch keine Bewertungen

- Illustrations: Greystroke: Jaya MadhavanDokument3 SeitenIllustrations: Greystroke: Jaya MadhavanvijayndranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marching to Freedom: Gandhi's Salt MarchDokument20 SeitenMarching to Freedom: Gandhi's Salt MarchFroilan BarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Farmer and His SonsDokument2 SeitenThe Farmer and His SonsAnonymous VP5OJCNoch keine Bewertungen

- General English AssignmentDokument16 SeitenGeneral English Assignmentbertil stefhaniyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANGGOTA KELOMPOK - The Legend of SangkuriangDokument5 SeitenANGGOTA KELOMPOK - The Legend of Sangkuriang11. Duta Dwi SaputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Pond Full of MilkDokument7 SeitenA Pond Full of MilkfizzyshadowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short StoriesDokument5 SeitenShort StoriesumaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerpen InggrisDokument4 SeitenCerpen InggrisAyu FirdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Needle TreeDokument10 SeitenThe Needle Tree惠琳孙100% (1)

- Guess The End JokesDokument10 SeitenGuess The End JokesMoldoveanu Constanta SilviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short StoriesDokument11 SeitenShort StoriesYingJAntoinetteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don't Look Behind, Look Ahead: A Story About Curiosity and AssumptionsDokument7 SeitenDon't Look Behind, Look Ahead: A Story About Curiosity and AssumptionsFitriani AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kumpulan Soal NarrativeDokument21 SeitenKumpulan Soal NarrativePutu Abhihita Sabda100% (1)

- Story Telling of Tangkuban PerahuDokument3 SeitenStory Telling of Tangkuban PerahuNadia Ananda PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Boy Who Broke The BankDokument14 SeitenThe Boy Who Broke The BankRamakrishnan GanesanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sangkuriang in EnglishDokument4 SeitenSangkuriang in EnglishFit100% (1)

- Landi Lonely PorcupineDokument2 SeitenLandi Lonely PorcupineHayyu SafiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Abu Ali Counted His DonkeysDokument4 SeitenWhen Abu Ali Counted His DonkeysKhotia Nur AqshoNoch keine Bewertungen

- National University of Modern Languages Islamabad: Pakistani LiteratureDokument3 SeitenNational University of Modern Languages Islamabad: Pakistani LiteratureAli RazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Story of GandhiDokument20 SeitenThe Story of GandhiRajesh100% (5)

- Teks Drama Tangkuban PerahuDokument5 SeitenTeks Drama Tangkuban PerahuOpie MayozNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Secret of The Golden KeyDokument53 SeitenThe Secret of The Golden KeyAndre SnymanNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Search of RamanandDokument28 SeitenIn Search of RamanandChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

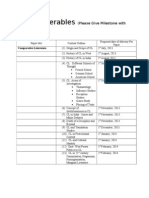

- Deliverable of Research ProjectDokument1 SeiteDeliverable of Research ProjectChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seeing Through The Other Translation TheoryDokument23 SeitenSeeing Through The Other Translation TheoryChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report On Academic TourDokument2 SeitenReport On Academic TourChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Story in Gujarati Dalit LiteratureDokument15 SeitenShort Story in Gujarati Dalit LiteratureChaitali Desai100% (1)

- Confessions of A Marathi Writer Vilas SarangDokument5 SeitenConfessions of A Marathi Writer Vilas SarangChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gross National HappinessDokument16 SeitenGross National HappinessChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Theory TermsDokument2 SeitenCritical Theory TermsHemang A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Pasts and National IdenityDokument9 SeitenCultural Pasts and National IdenityChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comp Lit NotesDokument2 SeitenComp Lit NotesChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uncovering Subaltern VoicesDokument8 SeitenUncovering Subaltern VoicesChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effiminate and Masculine in BengalDokument1 SeiteEffiminate and Masculine in BengalChaitali DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Richelieu and The Growth of French Power (Perkins 1900) ADokument435 SeitenRichelieu and The Growth of French Power (Perkins 1900) Atayl5720Noch keine Bewertungen

- War of The Immortals Daily Quiz QuestionsDokument22 SeitenWar of The Immortals Daily Quiz Questionshyuuuga0% (1)

- Hiranyagarbha - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument6 SeitenHiranyagarbha - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaRajesh PuniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Was Mi-Pham A Dialectical Monist? On A Recent Study of Mi-Pham's Interpretation of The Buddha-Nature EoryDokument24 SeitenWas Mi-Pham A Dialectical Monist? On A Recent Study of Mi-Pham's Interpretation of The Buddha-Nature EoryVajradharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LORD, I WANNA BE MEEK LIKE YOU: Benefits and How to Develop MeeknessDokument4 SeitenLORD, I WANNA BE MEEK LIKE YOU: Benefits and How to Develop Meeknesstre2001Noch keine Bewertungen

- December 9 RelaxDokument4 SeitenDecember 9 RelaxWealtH2013Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shidduch ResumeDokument7 SeitenShidduch Resumetcrmvpdkg100% (1)

- Featured Articles Weekly ColumnsDokument40 SeitenFeatured Articles Weekly ColumnsB. MerkurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concepts and ApproachesDokument12 SeitenConcepts and ApproachesDiego Rosas WellmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joshua - Judges in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPADokument296 SeitenJoshua - Judges in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPADavid F MaasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yama-Ashtakam Kannada PDF File13637Dokument3 SeitenYama-Ashtakam Kannada PDF File13637Shiva BENoch keine Bewertungen

- The Triadic "Politics-Economics-EthicsDokument293 SeitenThe Triadic "Politics-Economics-EthicsLeonidaNeamtuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karnad Folk Strategies PDFDokument5 SeitenKarnad Folk Strategies PDFshivaa111Noch keine Bewertungen

- AOS Discovery TempestDokument20 SeitenAOS Discovery TempestKrishna KannanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winchester by Heath, Sidney, 1872Dokument39 SeitenWinchester by Heath, Sidney, 1872Gutenberg.orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torments of The Grave in IslamDokument9 SeitenTorments of The Grave in IslamCrossMuslimsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Key Event in The Philippine History That I Have Struct in My Life As An Aspirant To Salesian Life Is The First Five Missionaries Here in The PhilippinesDokument3 SeitenThe Key Event in The Philippine History That I Have Struct in My Life As An Aspirant To Salesian Life Is The First Five Missionaries Here in The PhilippinesJeneric LambongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Welcoming New Employees GuideDokument12 SeitenWelcoming New Employees GuideAnggini PangestuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Morality Through MercyDokument39 SeitenUnderstanding Morality Through MercyJohn Feil JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- TimuwayDokument2 SeitenTimuwayGee DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mishnayot תבש תכסמ: ‘Parasha Digest - Acharei-KedoshimDokument2 SeitenMishnayot תבש תכסמ: ‘Parasha Digest - Acharei-KedoshimTheLivingTorahWeeklyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faisalabad Ramadan Calendar 2024 UrdupointDokument2 SeitenFaisalabad Ramadan Calendar 2024 Urdupointchalishahidiqbal380Noch keine Bewertungen