Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Assessing Quality of Student

Hochgeladen von

Samuel Laura HuancaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Assessing Quality of Student

Hochgeladen von

Samuel Laura HuancaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Assessing the Quality of Student Learning in Multimedia-Supported Project-based Learning Symposium Proposal AERA 2000 Creating Knowledge in the

21st Century: Insights from Multiple Perspectives Symposium Participants Barbara Means, SRI International, CHAIR Michael Simkins, Joint Venture: Silicon Valley Gail Britt, Central Middle School, San Carlos, CA Otak Jump, Ohlone Elementary School, Palo Alto, CA Karen A. Cole, Institute for Research on Learning William R. Penuel, SRI International Richard Lehrer, University of Wisconsin-Madison, DISCUSSANT Objective of the Symposium In this symposium we will present diverse approaches to addressing the problem of how to measure the quality of learning in classrooms where students design multimedia products in the context of project-based learning. We share studies conducted as part of the evaluation of the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project, a federally-funded Technology Innovation Challenge Grant now in its fourth year of implementation in California's Silicon Valley region. Through our symposium, we aim to provide promising examples of assessment and evaluation practices that can both help teachers improve student learning and provide researchers and policy makers with knowledge of how the effective use of multimedia technology can impact student achievement. Our symposium draws upon three perspectives: those of program director, classroom teacher, and professional researcher. The program director will present the process by which researchers and project staff jointly developed and implemented a rubric for measuring the quality of student projects exhibited at annual multimedia fairs sponsored by participating teams of schools. Two teachers will describe classroom assessment strategies they developed in partnership with the Institute for Research on Learning (IRL), and a researcher from IRL will discuss the impact of these assessment practices on teaching and learning. Two researchers from SRI International will discuss the development of a performance assessment and scoring rubric used to measure the impact of Multimedia Project participation on classroom learning. Significance of the Problem For many years, educators have noted the deep learning that can happen when students do long projects together. Learning through projects was an important part of Progressive Education in the early part of the twentieth century. The Project Method, as it was sometimes called (Kirkpatrick, 1918), was seen as a tool for engaging students in systematic, student directed inquiry. Dewey (1997) in particular believed that various crafts, including the graphic arts, afford great opportunity for training in self-reliant and

efficient social service (p. 168) and provide students with opportunities to encounter problems that require students to reflect and experiment to solve them. As the popularity of student-centered approaches to teaching and learning has grown in recent years, projects have again become the focus of attention of educators and researchers. Todays examples of project-based learning are similar to earlier practices in that they require students to focus over an extended period of time on the resolution of a real-world problem (Blumenfeld et al., 1991). Typically, through the course of completing a project, learners use multiple sources, collaborate with others, and apply cognitive tools to plan, conduct and evaluate possible solutions to the problem at hand. In this way, projects provide an opportunity for students to develop deep understanding of subject matter as they acquire new information and concepts and apply this new knowledge to a production task. Multimedia technology is a potentially powerful aid for structuring project-based work to engage student learning. Multimedia products create artifacts for teachers and students that can become the basis for ongoing reflection and critique, helping students to develop higher standards for their work over time. For example, Allen and Pea (1992) traced the joint construction of a set of expectations for student learning by teachers and students over the course of an extended student project involving the construction of multimedia presentations. They documented the ways that teachers and students negotiated a balance between a focus on design and content, and came to see the two elements of constructing a presentation as interdependent. In a similar study of projectbased learning using multimedia, Erickson and Lehrer (1998) researched the evolution of critical standards for judging the quality of student work. Over the course of two years involvement in projects, students and teachers came to develop shared representations of what constitutes a good project. In the two case studies cited above, multimedia technology alone was not sufficient to support student learning. In both these projects, teachers played a critical role by fostering and guiding student reflection about the quality of student work, both as it progressed and as students developed final multimedia products. Teachers used ongoing assessment to help drive student collaboration and learning. In our analyses of student learning in the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project, we provide additional examples of assessment tools that can support students' own developing understanding of what constitutes a quality multimedia project. We also go beyond previous case studies of project-based learning using multimedia by considering the ways that formative classroom assessment practices can be coordinated with program design and evaluation, so that the program design can be continuously improved and knowledge of effective practices can be distributed widely to researchers and policy makers. Symposium Presentations Michael Simkins, Joint Venture: Silicon Valley Network, will describe the overall program design and present the tool and method developed to judge the quality of student multimedia projects exhibited at annual, end-of-year fairs. These fairs were a critical component of the program design and were intended to motivate completion of projects, reward student and teacher effort, and foster community awareness of the ways in which multimedia technology can be applied in the classroom. Working together,

teachers, evaluators, and project staff created a scoring rubric based on the model of project-based learning espoused by the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project. The rubric allowed for projects to be rated on a five-point scale in each of three dimensions: content, collaboration, and multimedia. Scoring was done by panels of college-educated lay judges following 30-minute student interviews. Project scores were used as one source of data for measuring progress of the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project toward its stated goal of infusing the schools of Silicon Valley with an exemplary model of project-based learning supported by multimedia. In the two years the scoring process has been used, the proportion of projects rated "exemplary" has increased dramatically, from 22% to 50%. Gayle Britt, Central Middle School in San Carlos, CA, will describe assessment strategies she developed in partnership with the Institute for Research on Learning aimed at helping students judge the quality of HyperStudio stacks they created as part of a project focused on Chinese dynasties. Initially, Britt helped students create a checklist to judge the quality of their work and found that when students revised their work using this checklist, their comments focused almost exclusively on design issues and not on content. Britt worked with her class again to develop a set of content-focused criteria for judging the quality of their stacks. With the new student-generated checklist, students realized they knew more than they had incorporated into their stacks and recognized the need to incorporate more content into their stacks. In a second assessment laboratory, Britt worked with SRI researchers who were conducting a performance assessment in select Multimedia Project classrooms. Students were asked to develop criteria for assessing the quality of brochures they and other students had created as part of the assessment task. Students watched a video of domain content and design experts from the field before generating a first set of criteria. After scoring one brochure, students revised their checklist, reviewed the original instructions for the task, and scored a second brochure. Britt reports that through this process, students learned to become more specific in generating their checklists and to develop an appreciation of how to use the standards in a rubric or checklist, rather than their first impressions, as the basis for judging the quality of brochures. Otak Jump, Ohlone Elementary School in Palo Alto, CA, will describe a process he developed to help students reflect on their skill in collaboration as they participate in computer-supported project-based learning activities. The process involves a group discussion about the types of behaviors that will help reach the particular learning goals for the project. Students then begin work, and while they are working the teacher records short video segments showing students doing whatever they are doing. Either at the end of the session or at the beginning of the next class period, the group watches five minutes of video, and Jump points out specific behaviors that he wants students to learn from and solicits student comments about the behaviors they have seen. During this debrief, the question of behavior is framed as to which behaviors "helped" the group achieve their learning goals and which behaviors "hindered." The discussion focuses on describing the behaviors, not the people involved in doing the behaviors. Jump employed this process throughout the student multimedia projects this year and worked with the Institute on

Learning to document the effects of these strategies on the collaborative behavior of students. Karen A. Cole, Institute for Research on Learning, will outline the results of her study of the effects of the assessment strategies in Britts and Jumps classrooms. Cole found that ongoing, future-oriented formative assessment was effective improving student learning and extending teacher practice. Assessment was particularly effective in helping to solve problems particular to student-designed multimedia projects. These problems include learning enough academic subject matter, developing language for assessing quality in the new media, and helping students take advantage of the technology (rather than producing an on-line term paper). Video analysis of student work sessions and assessment events, combined with analysis of multiple revisions of students' multimedia projects, allowed us to trace how assessment events affected student work and assessment practices. Student projects became more content-rich as assessment progressed, and project design elements became more content-appropriate. Students developed language for talking about the quality of projects, and changed they way they evaluated a project's quality. As assessment progressed, they became more focused on particular qualities of a project and less focused on numerical scores. Teachers changed their view of assessment's function from measurement to supporting and enhancing learning. William R. Penuel and Barbara Means, SRI International, will describe the design, implementation, and results from a performance assessment aimed at measuring student problem solving skill in constructing products like the ones created by students in the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project. As part of their evaluation of the Multimedia Project, Means and Penuel set out to design a task that would be able to compare the performance of middle-school students in classrooms with experienced Multimedia Project teachers with middle-school students in classrooms where teachers used little technology or project-based learning methods. Two key constraints were addressed in the design: comparison classrooms lack of access to technology, and the need to provide content to classrooms that represented a number of core subject areas. SRI researchers worked in partnership with classroom teachers and their students, in particular Gayle Britt, to develop the outlines of a rubric that was later refined by researchers for scoring. Results showed that Multimedia Project students evidenced greater mastery of content, more sensitivity to their audience, and better design skills. The researchers will discuss the implications of the findings and plans for sharing knowledge of the programs effectiveness beyond the projects teachers. Symposium Format The chair will provide a brief overview of the session, outlining the theoretical and practical significance of the session. Each speaker will be given 10-15 minutes per presentation. The discussant will take 10-15 minutes to provide comments on each of the papers, and the remaining time for the session will be devoted to questions from the audience.

References Allen, C., & Pea, R. (1992). The social construction of genre in multimedia learning environments. Menlo Park, CA: Institute for Research on Learning. Blumenfeld, P.C., Soloway, E., Marx, R.W., Krajcik, J.S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398. Dewey, J. (1997). How we think. Mineola, NY: Dover. Erickson, J., & Lehrer, R. (1998). The evolution of critical standards as students design hypermedia documents. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7, 351-386. Kirkpatrick, W. H. (1918). The Project Method. Teachers College Record. Also reprinted in Schultz, F.(Ed.) Sources: Notable Selections in Education. Guilford, CT: The Dushkin Publishing Group.,Inc. pp.26 - 33.

Assessing the Quality of Student Learning in Multimedia-Supported Project-based Learning Symposium Proposal AERA 2000 Creating Knowledge in the 21st Century: Insights from Multiple Perspectives Symposium Participants Objective of the Symposium In this symposium we will present diverse approaches to addressing the problem of how to measure the quality of learning in classrooms where students design multimedia products in the context of project-based learning. We share studies conducted as part of the evaluation of the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project, a federally-funded Technology Innovation Challenge Grant now in its fourth year of implementation in California's Silicon Valley region. . Through our symposium, we aim to provide promising examples of assessment and evaluation practices that can both help teachers improve student learning and provide researchers and policy makers with knowledge of how the effective use of multimedia technology can impact student achievement. Our symposium draws upon three perspectives: those of program director, classroom teacher, and professional researcher. The program director will present the process by which researchers and project staff jointly developed and implemented a rubric for measuring the quality of student projects exhibited at annual multimedia fairs sponsored by participating teams of schools. Two teachers will describe classroom assessment strategies they developed in partnership with a national research institute, and a researcher from this institute will discuss the impact of these assessment practices on teaching and learning. Two researchers from another national research institute will discuss the development of a performance assessment and scoring rubric used to measure the impact of Multimedia Project participation on classroom learning. Significance of the Problem For many years, educators have noted the deep learning that can happen when students do long projects together. Learning through projects was an important part of Progressive Education in the early part of the twentieth century. The Project Method, as it was sometimes called (Kirkpatrick, 1918), was seen as a tool for engaging students in systematic, student directed inquiry. Dewey (1997) in particular believed that various crafts, including the graphic arts, afford great opportunity for training in self-reliant and efficient social service (p. 168) and provide students with opportunities to encounter problems that require students to reflect and experiment to solve them. As the popularity of student-centered approaches to teaching and learning has grown in recent years, projects have again become the focus of attention of educators and researchers. Todays examples of project-based learning are similar to earlier practices in that they require students to focus over an extended period of time on the resolution of a real-world problem (Blumenfeld et al., 1991). Typically, through the course of

completing a project, learners use multiple sources, collaborate with others, and apply cognitive tools to plan, conduct and evaluate possible solutions to the problem at hand. In this way, projects provide an opportunity for students to develop deep understanding of subject matter as they acquire new information and concepts and apply this new knowledge to a production task. Multimedia technology is a potentially powerful aid for structuring project-based work to engage student learning. Multimedia products create artifacts for teachers and students that can become the basis for ongoing reflection and critique, helping students to develop higher standards for their work over time. For example, Allen and Pea (1992) traced the joint construction of a set of expectations for student learning by teachers and students over the course of an extended student project involving the construction of multimedia presentations. They documented the ways that teachers and students negotiated a balance between a focus on design and content, and came to see the two elements of constructing a presentation as interdependent. In a similar study of projectbased learning using multimedia, Erickson and Lehrer (1998) researched the evolution of critical standards for judging the quality of student work. Over the course of two years involvement in projects, students and teachers came to develop shared representations of what constitutes a good project. In the two case studies cited above, multimedia technology alone was not sufficient to support student learning. In both these projects, teachers played a critical role by fostering and guiding student reflection about the quality of student work, both as it progressed and as students developed final multimedia products. Teachers used ongoing assessment to help drive student collaboration and learning. In our analyses of student learning in the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project, we provide additional examples of assessment tools that can support students' own developing understanding of what constitutes a quality multimedia project. We also go beyond previous case studies of project-based learning using multimedia by considering the ways that formative classroom assessment practices can be coordinated with program design and evaluation, so that the program design can be continuously improved and knowledge of effective practices can be distributed widely to researchers and policy makers. Symposium Presentations The first presenter will describe the overall program design and present the tool and method developed to judge the quality of student multimedia projects exhibited at annual, end-of-year fairs. These fairs were a critical component of the program design and were intended to motivate completion of projects, reward student and teacher effort, and foster community awareness of the ways in which multimedia technology can be applied in the classroom. Working together, teachers, evaluators, and project staff created a scoring rubric based on the model of project-based learning espoused by the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project. The rubric allowed for projects to be rated on a five-point scale in each of three dimensions: content, collaboration, and multimedia. Scoring was done by panels of college-educated lay judges following 30-minute student interviews. Project scores were used as one source of data for measuring progress of the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project toward its stated goal of infusing the schools of Silicon Valley with an exemplary model of project-based learning supported by

multimedia. In the two years the scoring process has been used, the proportion of projects rated "exemplary" has increased dramatically, from 22% to 50%. The second presenter will describe assessment strategies she developed in partnership with the first research institute aimed at helping students judge the quality of HyperStudio stacks they created as part of a project focused on Chinese dynasties. Initially, this presenter helped students create a checklist to judge the quality of their work and found that when students revised their work using this checklist, their comments focused almost exclusively on design issues and not on content. The presenter worked with her class again to develop a set of content-focused criteria for judging the quality of their stacks. With the new student-generated checklist, students realized they knew more than they had incorporated into their stacks and recognized the need to incorporate more content into their stacks. In a second assessment laboratory, the presenter worked with researchers who were conducting a performance assessment in select Multimedia Project classrooms. Students were asked to develop criteria for assessing the quality of brochures they and other students had created as part of the assessment task. Students watched a video of domain content and design experts from the field before generating a first set of criteria. After scoring one brochure, students revised their checklist, reviewed the original instructions for the task, and scored a second brochure. The presenter reports that through this process, students learned to become more specific in generating their checklists and to develop an appreciation of how to use the standards in a rubric or checklist, rather than their first impressions, as the basis for judging the quality of brochures. The third presenter will describe a process he developed to help students reflect on their skill in collaboration as they participate in computer-supported project-based learning activities. The process involves a group discussion about the types of behaviors that will help reach the particular learning goals for the project. Students then begin work, and while they are working the teacher records short video segments showing students doing whatever they are doing. Either at the end of the session or at the beginning of the next class period, the group watches five minutes of video, and the teacher points out specific behaviors that he wants students to learn from and solicits student comments about the behaviors they have seen. During this debrief, the question of behavior is framed as to which behaviors "helped" the group achieve their learning goals and which behaviors "hindered." The discussion focuses on describing the behaviors, not the people involved in doing the behaviors. The presenter employed this process throughout the student multimedia projects this year and worked with the Institute on Learning to document the effects of these strategies on the collaborative behavior of students. The fourth presenter will outline the results of her study of the effects of the assessment strategies in the second and third presenters classrooms. The researcher found that ongoing, future-oriented formative assessment was effective improving student learning and extending teacher practice. Assessment was particularly effective in helping to solve problems particular to student-designed multimedia projects. These problems include learning enough academic subject matter, developing language for

assessing quality in the new media, and helping students take advantage of the technology (rather than producing an on-line term paper). Video analysis of student work sessions and assessment events, combined with analysis of multiple revisions of students' multimedia projects, allowed us to trace how assessment events affected student work and assessment practices. Student projects became more content-rich as assessment progressed, and project design elements became more content-appropriate. Students developed language for talking about the quality of projects, and changed they way they evaluated a project's quality. As assessment progressed, they became more focused on particular qualities of a project and less focused on numerical scores. Teachers changed their view of assessment's function from measurement to supporting and enhancing learning. The fifth and sixth presenters will together describe the design, implementation, and results from a performance assessment aimed at measuring student problem solving skill in constructing products like the ones created by students in the Challenge 2000 Multimedia Project. As part of their evaluation of the Multimedia Project, the presenters set out to design a task that would be able to compare the performance of middle-school students in classrooms with experienced Multimedia Project teachers with middle-school students in classrooms where teachers used little technology or project-based learning methods. Two key constraints were addressed in the design: comparison classrooms lack of access to technology, and the need to provide content to classrooms that represented a number of core subject areas. Researchers worked in partnership with classroom teachers and their students, in particular the second presenter, to develop the outlines of a rubric that was later refined by researchers for scoring. Results showed that Multimedia Project students evidenced greater mastery of content, more sensitivity to their audience, and better design skills. The researchers will discuss the implications of the findings and plans for sharing knowledge of the programs effectiveness beyond the projects teachers. Symposium Format The chair will provide a brief overview of the session, outlining the theoretical and practical significance of the session. Each speaker will be given 10-15 minutes per presentation. The discussant will take 10-15 minutes to provide comments on each of the papers, and the remaining time for the session will be devoted to questions from the audience. References Allen, C., & Pea, R. (1992). The social construction of genre in multimedia learning environments. Menlo Park, CA: Institute for Research on Learning. Blumenfeld, P.C., Soloway, E., Marx, R.W., Krajcik, J.S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26, 369-398.

Dewey, J. (1997). How we think. Mineola, NY: Dover. Erickson, J., & Lehrer, R. (1998). The evolution of critical standards as students design hypermedia documents. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7, 351-386. Kirkpatrick, W. H. (1918). The Project Method. Teachers College Record. Also reprinted in Schultz, F.(Ed.) Sources: Notable Selections in Education. Guilford, CT: The Dushkin Publishing Group.,Inc. pp.26 - 33.

List of Participants

Means, Barbara, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Simkins, Michael, JVSV, 99 Almaden Blvd #700, San Jose, CA 95113 Gail B, Central MS, 828 Chestnut Street, San Carlos, CA 94070 Otak C, Ohlone ES, 950 Amarillo, Palo Alto, CA 94303 Karen A. D, IRL, 66 Willow Pl, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Penuel, William R., SRI Intl, 333 Ravenswood, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Richard Lehrer, WCER, 1025 W. Johnson St., Madison, WI, 53705

List of Participants

Means, Barbara, SRI International, 333 Ravenswood, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Simkins, Michael, JVSV, 99 Almaden Blvd #700, San Jose, CA 95113 Gail B, Central MS, 828 Chestnut Street, San Carlos, CA 94070 Otak C, Ohlone ES, 950 Amarillo, Palo Alto, CA 94303 Karen A. D, IRL, 66 Willow Pl, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Penuel, William R., SRI Intl, 333 Ravenswood, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Richard Lehrer, WCER, 1025 W. Johnson St., Madison, WI, 53705

Information for Index card: Assessing the Quality of Student Learning in Multimedia-Supported Project-based Learning Organizer: Penuel, William R. SRI International 333 Ravenswood, Mailstop BS116 Menlo Park, CA 94025 (650) 859-5001 Means, Barbara SRI International 333 Ravenswood Menlo Park, CA 94025 (650) 859-4004

Chair:

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- FNSACC512 Assessment Student InstructionsDokument20 SeitenFNSACC512 Assessment Student InstructionsHAMMADHRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authentic Assessment PDFDokument4 SeitenAuthentic Assessment PDFMatthewUrielBorcaAplacaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Tasks: Guide To Engaging Students in Meaningful LearningDokument29 SeitenPerformance Tasks: Guide To Engaging Students in Meaningful LearningEmy TalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPST - RP Module7, June2018Dokument32 SeitenPPST - RP Module7, June2018maxy waveNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 - SITXINV002 Maintain The Quality of Perishable Items Student GuideDokument55 Seiten2 - SITXINV002 Maintain The Quality of Perishable Items Student GuidePiyush Gupta0% (2)

- (PDF) (2003) Studying at A Distance A Guide For StudentsDokument201 Seiten(PDF) (2003) Studying at A Distance A Guide For StudentsShady Abuyusuf100% (4)

- TIP Module 3Dokument38 SeitenTIP Module 3Fatima Adil100% (7)

- Literacy Development in The Early Years Helping Children Read And-11-85Dokument75 SeitenLiteracy Development in The Early Years Helping Children Read And-11-85Anabelle Gines ArcillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rubric ExamplesDokument22 SeitenRubric ExamplesSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comunicación Horizontal y Vertical - Simpson 1959Dokument10 SeitenComunicación Horizontal y Vertical - Simpson 1959Samuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- P1434 PDFDokument6 SeitenP1434 PDFSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maturity Method: Atce-IDokument6 SeitenMaturity Method: Atce-ISamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Irregular Verbs ListDokument2 SeitenIrregular Verbs ListSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cam Clay Model STRDokument10 SeitenCam Clay Model STRSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ©+1960+Thomas+Telford +the+originalDokument1 Seite©+1960+Thomas+Telford +the+originalSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LevelsOfAssessment PDFDokument24 SeitenLevelsOfAssessment PDFSamuel Laura Huanca100% (1)

- EPA Hot Mix Asphalt Plants Mineral Products Industry PDFDokument63 SeitenEPA Hot Mix Asphalt Plants Mineral Products Industry PDFMariano David Pons MerinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Special Document For Civil Engineering Theory and Project: 0.1 Geotechnical WorldDokument1 SeiteSpecial Document For Civil Engineering Theory and Project: 0.1 Geotechnical WorldSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portland CementDokument10 SeitenPortland CementSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 15Dokument22 SeitenLecture 15Samuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Levels of AssessmentDokument7 SeitenLevels of AssessmentSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coo 31924003646225-47Dokument1 SeiteCoo 31924003646225-47Samuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 5Dokument14 SeitenCH 5Samuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundations Ch4Dokument62 SeitenFoundations Ch4stevehuppertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis, Design, Testing and Performance of FoundationsDokument23 SeitenAnalysis, Design, Testing and Performance of FoundationsNadim527Noch keine Bewertungen

- Squaring The CircleDokument21 SeitenSquaring The CircleSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3frg DPLDokument5 Seiten3frg DPLSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steel Pipe PilesDokument12 SeitenSteel Pipe PilesSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coo 31924003975681-19Dokument1 SeiteCoo 31924003975681-19Samuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Field Estimates Pile Capacity PDFDokument4 SeitenField Estimates Pile Capacity PDFAniculaesi MirceaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total Credits: 3 Credit Hours: 3 Lectures Per Week: Jhamad@mail - Iugaza.eduDokument2 SeitenTotal Credits: 3 Credit Hours: 3 Lectures Per Week: Jhamad@mail - Iugaza.eduSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SVOFFICE CatalogueDokument2 SeitenSVOFFICE Catalogue정관용Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chemical Reaction in Hydrated OPCDokument14 SeitenChemical Reaction in Hydrated OPCMohdhafizFaiz MdAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter One-Portland CementDokument28 SeitenChapter One-Portland CementRaghu VenkataNoch keine Bewertungen

- CementDokument51 SeitenCementSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CementDokument51 SeitenCementSamuel Laura HuancaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemical Reaction in Hydrated OPCDokument14 SeitenChemical Reaction in Hydrated OPCMohdhafizFaiz MdAliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salwan Public School, Gurgaon Session 2020-21 Classes III-V Term End - 1 Assessment (Datesheet & Syllabus) Dear ParentDokument8 SeitenSalwan Public School, Gurgaon Session 2020-21 Classes III-V Term End - 1 Assessment (Datesheet & Syllabus) Dear ParentSanjeevSinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume FinalDokument2 SeitenResume Finalapi-411104780Noch keine Bewertungen

- TTC Summary Curriculum Framework 2020Dokument70 SeitenTTC Summary Curriculum Framework 2020Florence UfituweNoch keine Bewertungen

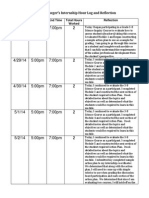

- 4/28/14 5:00pm 7:00pm 2: Lauren Krueger's Internship Hour Log and ReflectionDokument8 Seiten4/28/14 5:00pm 7:00pm 2: Lauren Krueger's Internship Hour Log and Reflectionlauren2260Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy EthicsDokument9 SeitenPhilosophy EthicsLee Somar100% (1)

- Lesson 2 ReflectionDokument1 SeiteLesson 2 Reflectionapi-177886209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Performance Rating (IPR) : Key Result Area (KRA) Actual Results Rating Score Quality Efficiency TimelinessDokument3 SeitenIndividual Performance Rating (IPR) : Key Result Area (KRA) Actual Results Rating Score Quality Efficiency TimelinessArmi Alcantara BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles: Standards: Mathematics and Science Compared To Technological LiteracyDokument9 SeitenArticles: Standards: Mathematics and Science Compared To Technological LiteracyfentjeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mac#4-Ilp - Week 1Dokument13 SeitenMac#4-Ilp - Week 1jhen aguilar100% (1)

- Standard 8 Reflection Continuous Growth Artifact 1Dokument11 SeitenStandard 8 Reflection Continuous Growth Artifact 1api-466313227Noch keine Bewertungen

- Esat ConsolidatorDokument30 SeitenEsat ConsolidatorSta. Rita Elementary School100% (1)

- Maths SymmetryDokument4 SeitenMaths Symmetryapi-360396514Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plugin Career PortfolioDokument18 SeitenPlugin Career PortfolioMie Azmi Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Indicator 1 Indicator 1: Curriculum & Learning Curriculum & LearningDokument11 SeitenIndicator 1 Indicator 1: Curriculum & Learning Curriculum & LearningAngeline MatalangNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Leadership Development Pathways - What Is It? ObjectivesDokument2 SeitenThe Leadership Development Pathways - What Is It? ObjectivesSaidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bagube X Ballera Chapter 1 3Dokument76 SeitenBagube X Ballera Chapter 1 3RODERICK GEROCHENoch keine Bewertungen

- TRF Questions and AnswersDokument8 SeitenTRF Questions and Answersjernalynluzano100% (1)

- Webbneneh 161809 Esh203 At1msDokument14 SeitenWebbneneh 161809 Esh203 At1msapi-296441201Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsDokument9 SeitenAn Analysis of Various Training Evaluation ModelsRajeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- FS 2 ModuleDokument16 SeitenFS 2 ModuleRoldan Agad Saren0% (1)

- FABDokument78 SeitenFABMkhairi HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poetry Lesson Plan-Humpty Dumpty Hey Diddle DiddleDokument3 SeitenPoetry Lesson Plan-Humpty Dumpty Hey Diddle Diddleapi-318070288Noch keine Bewertungen