Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Case Studies in Educational Research

Hochgeladen von

Raquel CarmonaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case Studies in Educational Research

Hochgeladen von

Raquel CarmonaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case studies in educational research To cite this reference: Hamilton, L.

(2011) Case studies in educational research, British Educational Research Association on-line resource. Available on-line at [INSERT WEB PAGE ADDRESS HERE] Last accessed _[insert date here] Dr Lorna Hamilton, University of Edinburgh April 2011. Contents Summary Why case study? Defining the case to be used Choosing your case Analysing and reporting the case References and further resources Summary Case study is often seen as a means of gathering together data and giving coherence and limit to what is being sought. But how can we define case study effectively and ensure that it is thoughtfully and rigorously constructed? This resource shares some key definitions of case study and identifies important choices and decisions around the creation of studies. It is for those with little or no experience of case study in education research and provides an introduction to some of the key aspects of this approach: from the all important question of what exactly is case study, to the key decisions around case study work and possible approaches to dealing with the data collected. At the end of the resource, key references and resources are identified which provide the reader with further guidance. Why case study? *What does case study do and what kind of data can it provide? *What is the purpose of your research and how can a case study approach help in fulfilling the aims of the project? Firstly, a case study approach is often used to build up a rich picture of an entity, using different kinds of data collection and gathering the views, perceptions, experiences and/or ideas of diverse individuals relating to the case. This approach provides what is termed rich data, as it can give the researcher in-depth insights into participants lived experiences within this particular context.

The use of multiple perspectives and different kinds of data collection is characteristic of high quality case study and lends weight to the validity of the findings. The use of two or more forms of data collection and/or the use of two or more perspectives is known as triangulation. Through triangulating data and/or perspectives, it is possible to gain a fuller and more robust picture of the case, enhancing claims to quality. Clarity over what case study is and what information and insights it might provide should then help to inform further research choices. For example, does the researcher wish to focus on depth of understanding through a single case or a number of cases, or does she/he wish to combine, for example, a wider overview of schools within the Local Authority in conjunction with a case study of one school to provide balance, breadth and depth? The key at this point is to reflect upon the essential qualities of case study and whether it connects with your research purpose and questions. Defining the case to be used Case study, then, focuses on the idea of a bounded unit which is examined, observed, described and analysed in order to capture key components of the case. The case might be, for example, a person, a group of particular professionals, an institution, a local authority etc. Robert Stake (1995) describes this kind of case study as holistic, it captures the essentials of what constitutes this person/this role etc. Stake also offers an alternative form of case study, and this is the model which is used most frequently by those in education: an instrumental or delimited case study (Stake, p3, 1995). In this latter form, the focus is usually on an issue, problem or dilemma etc within the case. The case, therefore, still exists as a bounded unit but the research focus does not attempt to provide a broad inclusive portrait. Instead, research processes are shaped by the particular aspect of the case which is of interest. Further conceptualisations of case study can be found in a forthcoming resource in 2012 (Hamilton, Corbett-Whittier and Fowler). Choosing your case Having determined that case study is right for your research, and having clarified the kind of case study you wish to undertake, the next step is to identify who or what the case will be. For example, if you have decided that your case study will focus upon a school-based issue, the next step will be decide how the school, or schools if more than one case study is desirable, will be chosen. As the case study work in this instance is qualitative in nature and limited in number, it is not possible or desirable to achieve sampling which is representative of a particular population. Instead, a purposive sampling which highlights schools with specific profiles might be helpful. An example of this from my own work illustrates possible choices. My project focused on the constructions of ability in comprehensive and independent schools. Since the focus was on gaining an in-depth picture of the construct of ability in relation to the institutions and the individuals within them, only a small number of schools could be involved in the creation of these

instrumental case studies (Hamilton, 2002). It was necessary to reflect on how schools might be chosen. When considering the two systems, it was clear that the comprehensive schools were operating under the idea of all-comer, equal opportunity institutions but there were some major differences. One key distinction was faith or non-denominational character; the other was the socio-economic status of the families sending children to schools. The schools chosen from the comprehensive system reflected these profiles a catholic comprehensive with a very mixed intake and high number of children entitled to free school meals and a comprehensive with a mixed intake but with a strong middle class intake. A similar review of the varied schools available in the independent system, highlighted key elements such as assessment of performance for entry/ informal interview for entry; highly competitive/ focus on nurture etc Since the project was to investigate constructions of ability, an additional component of this purposive sampling was the exam performance/profile of the school. In turn, this led to 4 schools being identified as having particular profiles. These choices provided case study schools with distinctive profiles and illustrated particular school types.

Comprehensive schools Mixed SES of pupils Faith school (Catholic) Limited success in exam league tables

Independent schools Informal interview pupils and parents for entry Comparatively new Success in exam league tables across a broad range of grades

Mixed SES but increasingly middle class Non-denominational

Selection formal / by assessment of ability Long established

High degree of success in exam league High degree of success in exam league tables tables towards upper grades

A summary of key choices/decisions so far 1. Issue/problem 2. Creating a research aim and questions 3. Holistic or instrumental case study approach 4. Who are the key individuals who might participate in order to answer your research questions? 5. Data collection tools which are most likely to provide you with the kind of data which will help you to answer your research questions? Some compromises may be necessary in terms of timescale, accessibility of participants etc 6. Sampling careful consideration of choices and key aspects which might have relevance for the project 7. Risk assessment: potential problems and how you might deal with them. Possible compromises/back up cases Analysing and reporting the case Having collected all the data for the case study and drawing also on any field notes you have made, analysing the data can seem quite daunting. There are certainly a number of ways to approach this and the references at the end of this paper will show authors whose work you will find helpful in this sphere. However, a starting point and straightforward approach might involve going back to your research questions and, taking each in turn, exploring the data and the possible answers, problems and conflicts which participants face in trying to respond. This can be a slightly messy process or at least one where it is necessary to go to and fro between research questions and data many times, exploring the commonalities and differences, the themes and exceptions which emerge (Miles and Hubermann, 1994). To further enhance quality, you might ask a colleague to read your work and access the data from the case in order to review key elements (Bassey, 1999). After developing the analysis further, and having spent some time verifying the validity of the findings, it is important to consider the extent to which this work can be generalised, if at all. One of the weaknesses, it is alleged, of case study is that the focus on depth, does not allow people to generalise findings and so may be of little value. However, this view of generalisation needs to be

questioned with regard to this kind of research. Stake (p7, 1995) argues that case study work may not transform understanding but instead it may refine it. He highlights commonality as a powerful element: [Many find] a commonality of process and situation. It startles us all to find our own perplexities in the lives of others. (Op cit) Basseys work (1999) suggests that fuzzy generalisation might be a means of generalising from a case in terms of typicalities: ... possible, or likely, or unlikely that what was found in the singularity will be found in similar situations elsewhere (op cit, p12) Ensure that there is a clear sense of how the project will deal with such issues when reporting case study, taking care to provide a clear outline of the decisions made and why, so that others can gauge the quality of the work. Reporting the case as a whole is often advised, before looking at the specific groups within the case being researched as this approach helps the reader to gain a sense of the bounded unit in relation to the dilemma etc being investigated. The reporting of case study may take different forms but for the purposes of this resource, consideration is briefly given to descriptive and analytical forms. A descriptive report would be built around a portrait of the case, drawing on rich detail and supported by clear evidence. However, an analytical account of a case builds upon a critical analysis of the stories generated about the people, relationships and purposes of the case. The former suggests a still image captured while the latter reflects an attempt to engage with moving images and actions. References and further resources There are a number of case study specific books available although they usually have a broad remit as they look across social sciences. An exception is the excellent book by Michael Bassey (1999) which focuses on educational settings. Another author, who writes extremely well and gives helpful insights into case study is Robert Stake. Both texts are in bold below. All the issues presented in this resource are discussed in more detail in Hamilton, Corbett-Whittier and Fowler (forthcoming). You may find as you explore the many methods texts available that writers may hold conflicting views which can be confusing. Nonetheless, the important thing to remember is that you will reach a point where you can evaluate the views given and finally establish your own decisions around case study. Case study

Bassey, M. (1999). Case Study Research in educational settings. Buckingham: Open University Press. Brown, P.A. (2008) 'A Review of the Literature on Case Study Research' in Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education 1/1. Hamilton, L.C. 2002. Constructing pupil identity: Personhood and ability. British Educational Research Journal 28, no. 4: 591602. Simon,H. (2009) Case Study Research in Practice. London:Sage. Stake, R. (1988) Case study methods in educational research: Seeking sweet water. In Complementary methods for research in education, ed. R.M. Jaeger and T. Barone, 253300. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association. Stake, R. (1995) The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage. Swanborn,P. (2010) Case Study Research. London:Sage. Thomas,G. (2011) How to do your case study. London:Sage. Yin, R. (2009) Applications of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Research methods Cresswell, J. 1998. Qualitative inquiry and research design. London: Sage. Denzin, N., Lincoln,Y. 1998. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. London: Sage. May, T. (1993) Social Research: Issues, methods and process, Milton Keynes: OUP Miles, M., and A.M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. London: Sage. Silverman, D. (2000) Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook. London: Sage Ethics British Educational Research Association (2004) Revised Ethical Guidelines for Educational

Research. Available online at: www.bera.ac.uk/publications/guides.php Coming in 2012 Hamilton,L., Corbett-Whittier,C., Fowler,Z. Using Case Studies in Education Research. London:Sage.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Defining Case Study in Education ResearchDokument24 SeitenDefining Case Study in Education Research:....Noch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Literature on Summative Assessment <40Dokument6 SeitenReview of Literature on Summative Assessment <40Jessemar Solante Jaron WaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Four Steps of Curriculum DevelopmentDokument4 SeitenFour Steps of Curriculum DevelopmentCarlo Zebedee Reyes GualvezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Management ReportDokument12 SeitenEducational Management ReportKRISTINE HUALDENoch keine Bewertungen

- Document Analysis As A Qualitative Research MethodDokument14 SeitenDocument Analysis As A Qualitative Research MethodJose Maria JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- ComprehensionDokument13 SeitenComprehensionAyush Varshney100% (1)

- Innovation in Educational AdministrationDokument4 SeitenInnovation in Educational AdministrationMLemeren LcrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic and Social Motivational Influences On StudentsDokument1 SeiteAcademic and Social Motivational Influences On StudentsAnujNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing a Framework for Promoting Internal EfficiencyDokument25 SeitenDeveloping a Framework for Promoting Internal EfficiencyiPhone Hacks100% (2)

- Managing The Learning EnvironmentDokument19 SeitenManaging The Learning Environmentjustin may tuyorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative ResearchDokument15 SeitenNarrative Researchapi-257674266Noch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Made TeacherDokument23 SeitenTeacher Made TeacherEducation MJ21Noch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review Educating Educators With Social Media, Charles WankelDokument5 SeitenBook Review Educating Educators With Social Media, Charles WankelEnal EmqisNoch keine Bewertungen

- C&I 6-77001 CurrentDokument30 SeitenC&I 6-77001 CurrentMarlyne VillarealNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education Policies of Pakistan A Critical LanalysisDokument51 SeitenEducation Policies of Pakistan A Critical LanalysisDrSyedManzoorHussain100% (1)

- Action Research Report On Homogeneous Groupings in The Mathematics ClassroomDokument10 SeitenAction Research Report On Homogeneous Groupings in The Mathematics ClassroomMargie BaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender EqualityDokument112 SeitenGender EqualityAnkit KapurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rethinking Education in Pakistan: Perceptions, Practices, and PossibilitiesDokument5 SeitenRethinking Education in Pakistan: Perceptions, Practices, and PossibilitiesKai MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multicultural Teaching Benefits All StudentsDokument9 SeitenMulticultural Teaching Benefits All StudentsIlene Dawn AlexanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Methods in Child PsychologyDokument26 SeitenResearch Methods in Child PsychologyAtthu MohamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formative Assessment OutputDokument56 SeitenFormative Assessment OutputJun JieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality Teaching in Higher EdDokument50 SeitenQuality Teaching in Higher Edsnafarooqi100% (1)

- Banks Dimensions of Multicultural EducationDokument1 SeiteBanks Dimensions of Multicultural Educationapi-252753724Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parent Involvement & Community PartnershipDokument19 SeitenParent Involvement & Community PartnershipMarkkenneth ColeyadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory and Practice of EducationDokument179 SeitenTheory and Practice of EducationAiziel AgonosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational LeadershipDokument4 SeitenEducational LeadershipBuen Saligan100% (1)

- Formative and Summative TestDokument3 SeitenFormative and Summative TestIcha Shailene Linao OndoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational ResearchDokument12 SeitenEducational ResearchThe Alliance100% (1)

- Philippines Basic Education Sector Transformation Program Independent Program Review ReportDokument76 SeitenPhilippines Basic Education Sector Transformation Program Independent Program Review ReportMarykristine LaudeNoch keine Bewertungen

- OrnekDokument14 SeitenOrnekHendriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences: Structural - FunctionalismDokument27 SeitenDisciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences: Structural - FunctionalismMargielane AcalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rubric For Instructional LeadershipDokument6 SeitenRubric For Instructional LeadershiparudenstineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pedagogical Approaches of Multi-Grade SchoolsDokument51 SeitenPedagogical Approaches of Multi-Grade SchoolsKathlea JaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Phenomenological Study On Reflective Teaching PracticeDokument121 SeitenA Phenomenological Study On Reflective Teaching PracticeTourism with P.KNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Article ReviewDokument4 SeitenEnglish Article ReviewESWARY A/P VASUDEVAN MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Participation RubricDokument1 SeiteClass Participation RubricPeter Jonas DavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Addressing The Future: Curriculum InnovationsDokument44 SeitenAddressing The Future: Curriculum InnovationsAallhiex EscartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Review On Inquiry LearningDokument15 SeitenArticle Review On Inquiry LearningRashyd Shaheed100% (1)

- Effectiveness of Professional Learning Communities at Gretchko Elementary School FinalDokument51 SeitenEffectiveness of Professional Learning Communities at Gretchko Elementary School Finalapi-277190928Noch keine Bewertungen

- Changing School ManagementDokument54 SeitenChanging School ManagementJorge SolarNoch keine Bewertungen

- E Learning. Challenges and Solutions - A Case Study PDFDokument8 SeitenE Learning. Challenges and Solutions - A Case Study PDFberyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Item Analysis BY: Florentina G. Reyes Item Analysis BY: Florentina G. ReyesDokument18 SeitenItem Analysis BY: Florentina G. Reyes Item Analysis BY: Florentina G. ReyesJulius TiongsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Linguistics: Syllabus and Course Information, Fall 2016 BS English: Semester IDokument1 SeiteIntroduction To Linguistics: Syllabus and Course Information, Fall 2016 BS English: Semester IMuhammad Saeed100% (1)

- Division of Leyte Organizational StructureDokument3 SeitenDivision of Leyte Organizational StructureJonas Miranda CabusbusanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment: Formative & Summative: Practices For The ClassroomDokument23 SeitenAssessment: Formative & Summative: Practices For The ClassroomNiaEka1331Noch keine Bewertungen

- PGRI UNIVERSITY ENGLISH EDUCATION SYLLABUSDokument4 SeitenPGRI UNIVERSITY ENGLISH EDUCATION SYLLABUSMiskiah PahruddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Educational Management Theory of BushDokument23 SeitenEducational Management Theory of BushValerie Joy Tañeza CamemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Research 04262018Dokument10 SeitenAction Research 04262018Queen Ann NavalloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8604, Assignment 1Dokument24 Seiten8604, Assignment 1Abdul Wajid100% (1)

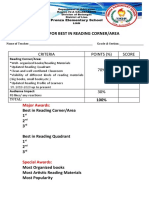

- Best Reading Area CriteriaDokument1 SeiteBest Reading Area CriteriaMelissa B. De Los ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methods of ResearchDokument5 SeitenMethods of Researchanon_794869624Noch keine Bewertungen

- Differences Between Norm-Referenced and Criterion-Referenced TestsDokument4 SeitenDifferences Between Norm-Referenced and Criterion-Referenced TestsKashif FaridNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Participation in Decision-Making in High School Achievement (Case Study On SMU Negeri 1 Manado)Dokument7 SeitenTeacher Participation in Decision-Making in High School Achievement (Case Study On SMU Negeri 1 Manado)inventionjournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trumpeta Report Educational PlanningDokument31 SeitenTrumpeta Report Educational PlanningJoanna Marie TrumpetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of Research on TeachingVon EverandHandbook of Research on TeachingCourtney BellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action Research Guide For Reflective Teachers: Fabian C. Pontiveros, JRDokument97 SeitenAction Research Guide For Reflective Teachers: Fabian C. Pontiveros, JRJun Pontiveros100% (1)

- Approaches To Curriculum DevelopmentDokument17 SeitenApproaches To Curriculum DevelopmentSajid AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research MenthodsDokument20 SeitenResearch MenthodsMerlyn SylvesterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content AnalysisDokument55 SeitenContent Analysisemamma hashirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education Research in Belize for Belize by Belizeans: Volume 1Von EverandEducation Research in Belize for Belize by Belizeans: Volume 1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomia ComparadaDokument8 SeitenAnatomia ComparadaRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application of PushDokument22 SeitenApplication of Push123123azxcNoch keine Bewertungen

- WPF Tutorial - Introduction To WPF LayoutDokument4 SeitenWPF Tutorial - Introduction To WPF LayoutRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TabelasDokument6 SeitenTabelaslrralvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 01Dokument13 SeitenCH 01Raquel Carmona100% (1)

- Interaction Curve Mx-My With N 30000 KN (Const) : Bending Moment (Strong Axis) (KNM)Dokument2 SeitenInteraction Curve Mx-My With N 30000 KN (Const) : Bending Moment (Strong Axis) (KNM)Raquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geotechnics in Romania: Case Studies: Technical University of Civil Engineering, BucharestDokument18 SeitenGeotechnics in Romania: Case Studies: Technical University of Civil Engineering, BucharestRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamics of Bridges 08Dokument28 SeitenDynamics of Bridges 08Raquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance Note Bracing Systems No. 1.03: ScopeDokument4 SeitenGuidance Note Bracing Systems No. 1.03: ScopeRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interaction Curve Mx-My With N 30000 KN (Const) : Bending Moment (Strong Axis) (KNM)Dokument2 SeitenInteraction Curve Mx-My With N 30000 KN (Const) : Bending Moment (Strong Axis) (KNM)Raquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Compacting ConcreteDokument87 SeitenSelf Compacting ConcreteLaura Amorim100% (1)

- Guidance Note Bracing and Cross Girder Connections No. 2.03: ScopeDokument5 SeitenGuidance Note Bracing and Cross Girder Connections No. 2.03: ScopeRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic ExcitationsDokument23 SeitenDynamic ExcitationsRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic ExcitationsDokument23 SeitenDynamic ExcitationsRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamics of Bridges 08Dokument28 SeitenDynamics of Bridges 08Raquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance Note Bracing and Cross Girder Connections No. 2.03: ScopeDokument5 SeitenGuidance Note Bracing and Cross Girder Connections No. 2.03: ScopeRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic ExcitationsDokument23 SeitenDynamic ExcitationsRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GN - 2 05 SecureDokument0 SeitenGN - 2 05 SecureCatalin CataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scalable p2pDokument12 SeitenScalable p2pRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torsion of Orthotropic Bars With L-Shaped or Cruciform Cross-SectionDokument15 SeitenTorsion of Orthotropic Bars With L-Shaped or Cruciform Cross-SectionRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GN - 2 04 SecureDokument4 SeitenGN - 2 04 SecureRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Downloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDDokument5 SeitenDownloads Unformal Factores de Carga LRFDRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- StiffenerDokument12 SeitenStiffenergholiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance Note Bracing Systems No. 1.03: ScopeDokument4 SeitenGuidance Note Bracing Systems No. 1.03: ScopeRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S0143974X98000649 MainDokument3 Seiten1 s2.0 S0143974X98000649 MainRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (5hdo $%HG/QHN DQG (0ludpehooDokument8 Seiten(5hdo $%HG/QHN DQG (0ludpehooRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSB07 Model Construction SpecificationDokument56 SeitenMSB07 Model Construction SpecificationCristian BlanaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discussion - Torsion of Rolled Steel Sections in Building StructuresDokument2 SeitenDiscussion - Torsion of Rolled Steel Sections in Building StructuresRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scalable p2pDokument12 SeitenScalable p2pRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slotted Hollow Section Connections Efficiency FactorsDokument0 SeitenSlotted Hollow Section Connections Efficiency FactorsRaquel CarmonaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karakteristik Morfologik Kambing Spesifik Lokal Di Kabupaten Samosir Sumatera UtaraDokument6 SeitenKarakteristik Morfologik Kambing Spesifik Lokal Di Kabupaten Samosir Sumatera UtaraOlivia SimanungkalitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument9 SeitenCase StudySidharth A.murabatteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advantage and Disadvantage Bode PlotDokument2 SeitenAdvantage and Disadvantage Bode PlotJohan Sulaiman33% (3)

- LESSON 1.1.2 - Online PlatformsDokument5 SeitenLESSON 1.1.2 - Online PlatformsAndree Laxamana100% (1)

- LESSON 1 Definition and Functions of ManagementDokument2 SeitenLESSON 1 Definition and Functions of ManagementJia SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adolescent HealthDokument19 SeitenAdolescent Healthhou1212!67% (3)

- Conservation of Arabic ManuscriptsDokument46 SeitenConservation of Arabic ManuscriptsDr. M. A. UmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Tips To Get Fair Skin Naturally PDFDokument2 Seiten15 Tips To Get Fair Skin Naturally PDFLatha SivakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab 7 RC Time ConstantDokument8 SeitenLab 7 RC Time ConstantMalith Madushan100% (1)

- AripiprazoleDokument2 SeitenAripiprazoleKrisianne Mae Lorenzo FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volleyball TermsDokument2 SeitenVolleyball TermskimmybapkiddingNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Petrolo 224252Dokument7 Seiten01 Petrolo 224252ffontanesiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mayans.M.C.S05E03.720p.WEB .x265-MiNX - SRTDokument44 SeitenMayans.M.C.S05E03.720p.WEB .x265-MiNX - SRTmariabelisamarNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbstractDokument23 SeitenAbstractaashish21081986Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arp ReflectionDokument3 SeitenArp Reflectionapi-317806307Noch keine Bewertungen

- LL - Farsi IntroductionDokument13 SeitenLL - Farsi IntroductionPiano Aquieu100% (1)

- Italian Renaissance Art: Prepared by Ms. Susan PojerDokument46 SeitenItalian Renaissance Art: Prepared by Ms. Susan Pojerragusaka100% (12)

- Chong Co Thai Restaurant LocationsDokument19 SeitenChong Co Thai Restaurant LocationsrajragavendraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Communications and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) - Marriage of Convenience or Shotgun WeddingDokument11 SeitenMarketing Communications and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) - Marriage of Convenience or Shotgun Weddingmatteoorossi100% (1)

- Ds Mini ProjectDokument12 SeitenDs Mini ProjectHarsh VartakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guide Number 5 My City: You Will Learn To: Describe A Place Tell Where You in The CityDokument7 SeitenGuide Number 5 My City: You Will Learn To: Describe A Place Tell Where You in The CityLUIS CUELLARNoch keine Bewertungen

- AffirmativedefensemotorvehicleDokument3 SeitenAffirmativedefensemotorvehicleKevinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Management: Amit Pandey +91-7488351996Dokument15 SeitenMarketing Management: Amit Pandey +91-7488351996amit pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Con Men ScamsDokument14 SeitenCon Men ScamsTee R TaylorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Métodos de Reabilitação para Redução Da Subluxação Do Ombro Na Hemiparesia pós-AVC Uma Revisão SistemátDokument15 SeitenMétodos de Reabilitação para Redução Da Subluxação Do Ombro Na Hemiparesia pós-AVC Uma Revisão SistemátMatheus AlmeidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is.14858.2000 (Compression Testing Machine)Dokument12 SeitenIs.14858.2000 (Compression Testing Machine)kishoredataNoch keine Bewertungen

- QP ScriptDokument57 SeitenQP ScriptRitesh SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Technology To Reduce Yarn WastageDokument3 SeitenNew Technology To Reduce Yarn WastageDwi Fitria ApriliantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50 Important Quotes You Should Pay Attention To in Past The Shallows Art of Smart EducationDokument12 Seiten50 Important Quotes You Should Pay Attention To in Past The Shallows Art of Smart EducationSailesh VeluriNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Investigation of The Reporting of Questionable Acts in An International Setting by Schultz 1993Dokument30 SeitenAn Investigation of The Reporting of Questionable Acts in An International Setting by Schultz 1993Aniek RachmaNoch keine Bewertungen