Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Borges y El Tiempo en Rilke

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous I5oA4X59iOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Borges y El Tiempo en Rilke

Hochgeladen von

Anonymous I5oA4X59iCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Borgess Rilkian Temporality Ten years after Rilkes death Jorge Luis Borges wrote his Historia de la Eternidad

in Argentina. Recounting the pagan, Christian and modern understandings of time, Borges reminds the reader of the Gnostic influence upon the Christian understanding of eternity. The Gnostic belief that God the father preceded both the son (the word made flesh) and the spirit nullified the concept of the trinity. The Churchs refutation of this heresy resulted in a new understanding of eternity. Aeternitas est merum hodie, est immediate et lucida fruitio rerum infinitarum (eternity is simply today, it is the immediate and lucid enjoyment of the things of infinity) (27). The reason that this notion of eternity is coupled with the doctrine of the trinity is quite simple. If there is no unity of the three, that is if Christ is not identifiable with God, then Jesus is but an accident of history. He would be incapable of offering divine redemption. The whole notion of Christianity would lose its timeless eternal character. 271 The trinity creates a notion of eternity in which all three divine aspects are an eternal unity not subject to the fleeting nature of time. All three coincide together. There is no vacant God acting before time. Thus eternity is not just the absence of time rather the contemporary and total intuition of all fractions of time (29-30). Borges also connects this to the expression of Yahweh in the Hebrew Scriptures as I am who am, to Boethius notion that aeternitas est interminabilis vitae tota et perfect possession (eternity is all of life perpetual and perfect possession), and to the idea that eternity is an attribute of the unlimited mind of God (31-32). Eternity is a product of Gods perception, or even of his imagination or possible imagination. Borges irony is not lost on the reader when he writes: El universo requiere la eternidad. Los telogos no ignoran que si la atencin del Seor se desviara un solo segundo de mi derecha mano que escribe, sta recaera en la nada, como si la fulminara un fuego sin luz. Por eso afirman que la conservacin de este mundo es una perpetua creacin y que los verbos conservar y crear, tan enemistados aqu, son sinnimos en el Cielo (36). This notion of divine conservation / creation is the same as Rilkes only it has been secularized. The world is a constant creation of God. It never ceases. Eternity is the ceaseless activity of divine intelligence experiencing all things (even the possible) simultaneously. Borges compares this theological notion to the idea that something similar exists for the artist. Eternity is now the contemplation of the artist. This is like Schopenhauers negation of the will (a product of time) through art. It is the Promethean Gnostic wrestling the perpetual creativity away from God and granting it to poetic imagination. This is very similar to Rilkes attempt to make the visible invisible through art, preserving it forever. Gesang ist Dasein and Orpheus is ein zum Rhmen Bestellter. Rilke is conserving the past by bridging it to the immediacy of the present. Rilkes 272 Gnostic duality is the necessity of eternity in his universe. Human eternity is poetic imagination. And that imagination is the unifier (Orpheus) of Sein and Bewutsein. Marquard contends that modern human beings cannot endure the absoluteness of God. Rilkes poetry suggests that the artist cannot do without it. Borges ends his history of eternity by expressing his own idea in terms of a unity of experience. Eternity, which was once the product of the mind of God, is now the product of the poet. Eternity becomes the invisible perception of unity with the world. As Borges says regarding an intense experience of a place that he has not visited in many years:

La escribo, ahora as: Esa pura representacin de hechos homogneos noche en serenidad, parecita lmpida, olor provinciano de la madreselva, barro fundemental no es meramente idntica a la que hubo en esa esquina hace tantos aos; es, sin parecidos ni repeticiones, la misma. El tiempo, si podemos intuir esa identidad, es una delusin: la indiferencia e inseparabilidad de un momento de su aparente ayer y otro de su aparente hoy, bastan para desintegrarlo (43). Borges locates eternity in the ability to unite past, present and future into the immediacy of an intense experience caught in a poetic moment. This is in essence the idea that Rilke conveyed to his Polish translator regarding the elegies eleven years earlier in 1925: Lebens- und Todesbejahung erweist sich als Eines in den Elegien. Das eine zuzugeben ohne das Andere, sei, so wird hier erfahren und gefeiert, eine schlielich alles Unendliche ausschlieende Einschrnkung. Der Tod ist die uns abgekehrte, von uns unbeschienene Seite des Lebens: wir mssen versuchen, das greste Bewutsein unseres Daseins zu leisten, das in beiden unabgegrenzten Bereichen zu Hause ist, aus beiden unerschpflich genhrt...Die wahre Lebensgestalt reicht durch beide Gebiete, das Blut des gresten Kreislaufs treibt durch beide: es gibt weder ein Diesseits noch Jenseits, sondern die groe Einheit, in der die uns bertreffenden Wesen, die Engel, zu Hause sind (Briefe 3: 896). 273 It is clear that Rilke has a two-world dualism at heart that he wishes to unite into one super-polar consciousness. God no longer inhabits the other side of art, only the angels remain. The poet will conjure up Orpheus to join the two. The infinite imagination of God that made the universe whole is now the domain of the artist and the modern individual that can internalize experience and time into personal eternity. Rilkes eternity proves impossible without the Gnostic isolation, a Deus absconditus of personal time.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Tarjuman Al-Quran Vol-IDokument253 SeitenThe Tarjuman Al-Quran Vol-IAdeel MahmoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Document 3Dokument2 SeitenDocument 3Ruby vittoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

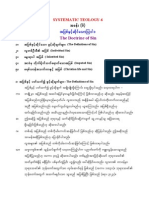

- Systematic Teology 6Dokument4 SeitenSystematic Teology 6Gm Cf67% (3)

- Must Faith Endure For Salvation To Be SureDokument5 SeitenMust Faith Endure For Salvation To Be SureJesus LivesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Khutbatul HaajahDokument2 SeitenKhutbatul HaajahMohammad Twaha Jaumbocus67% (3)

- Book Review Reclaim Your HeartDokument7 SeitenBook Review Reclaim Your HeartShaheer KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 John Bible StudyDokument26 Seiten1 John Bible StudyM. Baxter100% (3)

- Deleuze and Absolute Immanence: Achieving Fully Immanent InquiryDokument10 SeitenDeleuze and Absolute Immanence: Achieving Fully Immanent InquiryStefi GrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unlikely Heroes of The Old Testament JonahDokument2 SeitenUnlikely Heroes of The Old Testament JonahJustin AllisonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solemnity of The Most Holy TrinityDokument3 SeitenSolemnity of The Most Holy TrinityObyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Light in IslamDokument18 SeitenLight in IslamMuhamedOsmanagicNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Attributes of God - David Hocking PDFDokument262 SeitenThe Attributes of God - David Hocking PDFbonzayoyo0% (2)

- Basic Orientation Seminar On Youth Apostolate 2Dokument3 SeitenBasic Orientation Seminar On Youth Apostolate 2Cyrus GerozagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Early Christian ArtDokument8 SeitenEarly Christian ArtVidushiSharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negative Theology and Theological Hermeneutics - The Particularity of Naming God - BoeveDokument13 SeitenNegative Theology and Theological Hermeneutics - The Particularity of Naming God - BoeveMike NicholsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dark Night of The Soul in The Lonergan PerspectiveDokument10 SeitenDark Night of The Soul in The Lonergan Perspectiveemosekho100% (1)

- Entering Into The Realm of Non ExistenceDokument11 SeitenEntering Into The Realm of Non ExistenceAnonymous7891Noch keine Bewertungen

- CBT Exam For Geds 420 Elongated EducationDokument7 SeitenCBT Exam For Geds 420 Elongated EducationdemolaojaomoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living A Godly LifeDokument2 SeitenLiving A Godly LifeOsicran Yggerg GresyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disciple Making Pastoral Care Within Small Groups OriginalDokument15 SeitenDisciple Making Pastoral Care Within Small Groups OriginalRobert C100% (1)

- Gnanasarikai PDFDokument43 SeitenGnanasarikai PDFNadarajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- You're Somebody Special To God - Jerry SavelleDokument11 SeitenYou're Somebody Special To God - Jerry SavelleinacrapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voegelin Eric On Hegel A Study in Sorcery 1Dokument34 SeitenVoegelin Eric On Hegel A Study in Sorcery 1Ryan Vu100% (2)

- Illuminating Faith - An Invitation To TheologyDokument176 SeitenIlluminating Faith - An Invitation To TheologyzimmezummNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romans, Nicnt, MooDokument18 SeitenRomans, Nicnt, Moofauno_ScribdNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Omega Heresy in AdventismDokument16 SeitenThe Omega Heresy in AdventismDERRICK D. GILLESPIE (Mr.)100% (2)

- 4 - The Collected Writings of James Henley ThornwellDokument648 Seiten4 - The Collected Writings of James Henley Thornwellds1112225198Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adventist Muslim RelationsDokument16 SeitenAdventist Muslim Relationsdonodhiambo51100% (1)

- Brian Daley On HumilityDokument20 SeitenBrian Daley On Humilityingmarvazquez0% (1)

- The Compassion of JesusDokument33 SeitenThe Compassion of JesusJosephNoch keine Bewertungen