Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

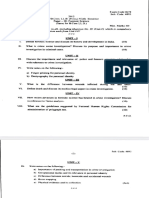

Labor Cases 1

Hochgeladen von

KayeCie RLOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Labor Cases 1

Hochgeladen von

KayeCie RLCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Maternity Childrens Hospital vs. Secretary of Labor G.R. No.

78909 June 30 1984 Labor Law Defined Facts: Petitioner is a semi-government hospital, managed by the Board of Directors of the Cagayan de Oro Women's Club and Puericulture Center, headed by Mrs. Antera Dorado, as holdover President. The hospital derives its finances from the club itself as well as from paying patients, averaging 130 per month. It is also partly subsidized by the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office and the Cagayan De Oro City government. Petitioner has forty-one (41) employees. Aside from salary and living allowances, the employees are given food, but the amount spent therefor is deducted from their respective salaries (pp. 77-78, Rollo). On May 23, 1986, ten (10) employees of the petitioner employed in different capacities/positions filed a complaint with the Office of the Regional Director of Labor and Employment, Region X, for underpayment of their salaries and ECOLAS, which was docketed as ROX Case No. CW-71-86. The Regional Director issued and order based on the reports of the Labor Standard and Welfare Officers, directing payment of P723, 888.58 representing underpayment of wages and ECOLAs to all the petitioners employees. Petitioner appealed to the Minister of Labor and Employment which modified the decision as to the period for the payment ECOLAs only. A motion for reconsideration was filed by petitioner and was denied by the Secretary of Labor. Held: Labor standards refer to the minimum requirements prescribed by existing laws, rules, and regulations relating to wages, hours of work, cost of living allowance and other monetary and welfare benefits, including occupational, safety, and health standards (Section 7, Rule I, Rules on the Disposition of Labor Standards Cases in the Regional Office, dated September 16, 1987).

Calalang vs. Williams Case Digest Calalang vs. Williams [GR 47800, 2 December 1940]

Facts: The National Traffic Commission, in its resolution of 17 July 1940, resolved to recommend to the Director of Public Works and to the Secretary of Public Works and Communications that animal-drawn vehicles be prohibited from passing along Rosario Street extending from Plaza Calderon de la Barca to Dasmarias Street, from 7:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and from 1:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.; and along Rizal Avenue extending from the railroad crossing at Antipolo Street to Echague Street, from 7 a.m. to 11 p.m., from a period of one year from the date of the opening of the Colgante Bridge to traffic. The Chairman of the National Traffic Commission, on 18 July 1940, recommended to the Director of Public Works the adoption of the measure proposed in the resolution, in pursuance of the provisions of Commonwealth Act 548, which authorizes said Director of Public Works, with the approval of the Secretary of Public Works and Communications, to promulgate rules and regulations to regulate and control the use of and traffic on national roads. On 2 August 1940, the Director of Public Works, in his first indorsement to the Secretary of Public Works and Communications, recommended to the latter the approval of the recommendation made by the Chairman of the National Traffic Commission, with the modification that the closing of Rizal Avenue to traffic to animal-drawn vehicles be limited to the portion thereof extending from the railroad crossing at Antipolo Street to Azcarraga Street. On 10 August 1940, the Secretary of Public Works and Communications, in his second indorsement addressed to the Director of Public Works, approved the recommendation of the latter that Rosario Street and Rizal Avenue be closed to traffic of animal-drawn vehicles, between the points and during the hours as indicated, for a period of 1 year from the date of the opening of the Colgante Bridge to traffic. The Mayor of Manila and the Acting Chief of Police of Manila have enforced and caused to be enforced the rules and regulations thus adopted. Maximo Calalang, in his capacity as a private citizen and as a taxpayer of Manila, brought before the Supreme court the petition for a writ of prohibition against A. D. Williams, as Chairman of the National Traffic Commission; Vicente Fragante, as Director of Public Works; Sergio Bayan, as Acting Secretary of Public Works and Communications; Eulogio Rodriguez, as Mayor of the City of Manila; and Juan Dominguez, as Acting Chief of Police of Manila Issues: Whether or not there is a undue delegation of legislative power? Ruling: There is no undue deleagation of legislative power. Commonwealth Act 548 does not confer legislative powers to the Director of Public Works. The authority conferred upon them and under which they promulgated the rules and regulations now complained of is not to determine what public policy demands but merely to carry out the legislative policy laid down by the National Assembly in said Act, to wit, to promote safe transit upon and avoid obstructions on, roads and streets designated as national roads by acts of the National Assembly or by executive orders of the President of the Philippines and to close them temporarily to any or all classes of traffic whenever the condition of the road or the traffic makes such action necessary or advisable in the public convenience and interest. The delegated power, if at all, therefore, is not the determination of what the law shall be, but merely the ascertainment of the facts and circumstances upon which the application of said law is to be predicated. To promulgate rules and regulations on the use of national roads and to determine when and how long a national road should be closed to traffic, in view of the condition of the road or the traffic thereon and the requirements of public convenience and interest, is an administrative function which cannot be directly discharged by the National Assembly. It must depend on the discretion of some other government official to whom is confided the duty of determining whether the proper occasion exists for executing the law. But it cannot be said that the exercise of such discretion is the making of the law.

People vs Vera Reyes G..R. No. L-45748 April 5, 1939 Facts: The defendant was charged in the Court of First Instance of Manila by the assistant city fiscal with a violation of Act No. 2549, as amended by Acts Nos. 3085 and 3958. The information alleged that from September 9 to October 28, 1936, the accused, in his capacity as president and general manager of the Consolidated Mines, having engaged the services of Severa Velasco de Vera as stenographer, at an agreed salary of P35 a month willfully and illegally refused to pay the salary of said stenographer corresponding to the above-mentioned period of time, which was long due and payable, in spite of her repeated demands. After the hearing, the court sustained the demurrer, declaring unconstitutional the last part of section 1 of Act No. 2549 as last amended by Act No. 3958, which considers as an offense the facts alleged in the information, for the reason that it violates the constitutional prohibition against imprisonment for debt, and dismissed the case, with costs de oficio. The fiscal appealed from said order. In the appeal, the Solicitor-General contends that the court erred in declaring Act No. 3958 unconstitutional, and in dismissing the cause. The last part of section 1 of Act No. 2549, as last amended by section 1 of Act No. 3958 considers as illegal the refusal of an employer to pay, when he can do so, the salaries of his employees or laborers on the fifteenth or last day of every month or on Saturday of every week, with only two days extension, and the nonpayment of the salary within the periods specified is considered as a violation of the law. The same Act exempts from criminal responsibility the employer who, having failed to pay the salary, should prove satisfactorily that it was impossible to make such payment. Issue: (a) W/N the last part of section 1 of Act No. 2549 as last amended by Act No. 3958 is constitutional and valid? Held: The court held that this provision is null because it violates the provision of section 1 (12), Article III, of the Constitution, which provides that no person shall be imprisoned for debt. We do not believe that this constitutional provision has been correctly applied in this case. A close perusal of the last part of section 1 of Act No. 2549, as amended by section 1 of Act No. 3958, will show that its language refers only to the employer who, being able to make payment, shall abstain or refuse to do so, without justification and to the prejudice of the laborer or employee. An employer so circumstanced is not unlike a person who defrauds another, by refusing to pay his just debt. In both cases the deceit or fraud is the essential element constituting the offense. The first case is a violation of Act No. 3958, and the second is estafa punished by the Revised Penal Code. In either case the offender cannot certainly invoke the constitutional prohibition against imprisonment for debt. The Court of Appeal held that the last part of section 1 of Act No. 2549, as last amended by section 1 of Act No. 3958, is valid, and reversed the appealed order with instructions to the lower court to proceed with the trial of the criminal case until it is terminated, without special pronouncement as to costs in this instance. So ordered.

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, plaintiffappellee, vs. JULIO POMAR, defendant-appellant. G.R. No. L-22008 November 3, 1924 Facts: The accused being the manager and person in charge of La Flor de la Isabela, a tobacco factory pertaining to La Campania General de Tabacos de Filipinas, a corporation duly authorized to transact business and the petitioner Macaria Fajardo, whom he granted vacation leave which began on the 16th d,y of July, 1923, by reason of her pregnancy, did then and there willfully, unlawfully, and feloniously fail and refuse to pay to said woman the sum of eighty pesos (P80), Philippine currency, to which she was entitled as her regular wages corresponding to thirty days before and thirty days after her delivery and confinement which took place on the 12th day of August, 1923, despite and over the demands made by her, the said Macaria Fajardo, upon said accused, to do so. To said complaint, the defendant contended that the provisions of said Act No. 3071, upon which the complaint was based were illegal, unconstitutional and void. The lower court, found the defendant guilty of the alleged offense described in the complaint, and sentenced him to pay a fine of P50, in accordance with the provisions of section 15 of said Act, to suffer subsidiary imprisonment in case of insolvency, and to pay the costs. From that sentence the defendant appealed, and now makes the following assignments of error: That the court erred in overruling the demurrer; in convicting him of the crime charged in the information; and in not declaring section 13 of Act No. 3071, unconstitutional. Issue: Whether or not the provisions of sections 13 and 15 of Act No. 3071 are a reasonable and lawful exercise of the police power of the state Held: Said section 13 was enacted by the Legislature of the Philippine Islands in the exercise of its supposed police power, with the praiseworthy purpose of safeguarding the health of pregnant women laborers in "factory, shop or place of labor of any description," and of insuring to them, to a certain extent, reasonable support for one month before and one month after their delivery. The statute now under consideration is attacked upon the ground that it authorizes an unconstitutional interference with the freedom of contract including within the guarantees of the due process clause of the 5th Amendment. That the right to contract about one's affairs is a part of the liberty of the individual protected by this clause is settled by the decision of this court, and is no longer open to question. The law takes account of the necessities of only one party to the contract. It ignores the necessities of the employer by compelling him to pay not less than a certain sum, not only whether the employee is capable of earning it, but irrespective of the ability of his business to sustain the burden, generously leaving him, of course, the privilege of abandoning his business as an alternative for going on at a loss. Liberty includes not only the right to labor, but to refuse to labor, and, consequently, the right to contract to labor or for labor, and to terminate such contracts, and to refuse to make such contracts.. Hence, we are of the opinion that this Act contravenes those provisions of the state and Federal constitutions, which guarantee that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law. Clearly, therefore, the law has deprived, every person, firm, or corporation owning or managing a factory, shop or place of labor of any description within the Philippine Islands, of his right to enter into contracts of employment upon such terms as he and the employee may agree upon. The law creates a term in every such contract, without the consent of the parties. Such persons are, therefore, deprived of their liberty to contract. The constitution of the Philippine Islands guarantees to every citizen his liberty and one of his liberties is the liberty to contract. It has been decided in a long line of decisions of

the Supreme Court of the United States, that the right to contract about one's affairs is a part of the liberty of the individual, protected by the "due process of law" clause of the constitution. The rule in this jurisdiction is, that the contracting parties may establish any agreements, terms, and conditions they may deem advisable, provided they are not contrary to law, morals or public policy. (Art. 1255, Civil Code.) For all of the foregoing reasons, we are fully persuaded, under the facts and the law, that the provisions of section 13, of Act No. 3071 of the Philippine Legislature, are unconstitutional and void, in that they violate and are contrary to the provisions of the first paragraph of section 3 of the Act of Congress of the United States of August 29, 1916. (Vol. 12, Public Laws, p. 238.)

CEREZO VS THE ATLANTIC & PACIFIC COMPANYG.R. No. L-10107 Date:February 4, 1916 Plaintiff- appellant:Clara Cerezo Defendant-appellant: The Atlantic Gulf & Pacific Company FACTS: The deceased was an employee of the defendant as a day laborer on the 8th of July, 1913,assisting in laying gas pipes on Calle Herran in the city of Manila. The digging of the trench wascompleted both ways from the cross-trench in Calle Paz, and the pipes were laid therein up to that point.The men of the deceased's gang were filling the west end, and there was no work in the progress at theeast end of the trench. Shortly after the deceased entered the trench at the east end to answer a call ofnature, the bank caved in, burying him to his neck in dirt, where he died before he could be released. Ithas not been shown that the deceased had received orders from the defendant to enter the trench at thispoint; nor that the trench had been prepared by the defendant as a place to be used as a water-closet;nor that did the defendant acquiesce in the using of this place for these purposes. The trench at the placewhere the accident occurred was between 3 and 4 feet deep. Nothing remained to be done there exceptto refill the trench as soon as the pipes were connected. The refilling was delayed at that place until thecompletion of the connection. At the time of the accident the place where the deceased's duty of refillingthe trench required him to be was at the west end. There is no contention that there was any dangerwhatever in the refilling of the trench.An action for damages was instated against the defendant for negligently causing the death of theplaintiff's son, Jorge Ocumen, on the 7th of July, 1913The plaintiff insists that the defendant was negligent in failing to shore or brace the trench at theplace where the accident occurred. While, on the other hand, the defendant urges (1) that it was under noobligation, in so far as the deceased was concerned, to brace the trench, in the absence of a showingthat the soil was of a loose character or the place itself was dangerous, and (2) that although the relationof master and servant may not have ceased, for the time being, to exist, the defendant was under no dutyto the deceased except to do him no intentional injury, and to furnish him with a reasonably safe place to work judgment was entered in a favor of the plaintiff for the sum of 1,250.00, together with interestand costs. Defendant appealed. ISSUES: 1. Whether or not the plaintiff has a right to recover for damages under the Employers Liability Act (Act No. 1874) or the Civil Code; and 2. Whether or not it is necessary to determine the effect of the former upon the law of industrialaccidents in this country? HELD: 1. The Plaintiff cannot recover from neither laws, an overwhelming jurisprudence holds master wasbound to exercise that measure of care which reasonably prudent men take under similarcircumstances. But the master was not an insurer and was not required to provide the safestpossible plant or to adopt the latest improvements or to warrant against latent defects which areasonable inspection did not disclose. It was only necessary that the danger in the work be notenhanced through his fault. It is provided further that;

the right of the master to shift responsibility for the performance of all or at least most of these personal duties to the shoulders of a subordinate and thereby escape liability for the injuries suffered by his workmen through his non-performance of these duties, was,in England, definitely settled by the House of Lords in the case of Wilson vs. Merry (L.R.1 H.L. Sc. Appl Cas., 326; 19 Eng. Rul. Cas., 132). This was just two years before the enactment of the Employers' Liability Act of 1880, and no doubt the full significance of such a doctrine was one of the impelling causes which expedited the passage of the Act, and chiefly accounts for the presence in it of subsection 1 of section 1. The cause of Ocumen's death was not the weight of the earth which fell upon him, butwas due to suffocation. He was sitting or squatting when the slide gave way. Had he been evenhalf-erect, it is highly probable that he would have escaped suffocation or even serious injury.Hence, the accident was of a most unusual character. Experience and common sensedemonstrate that ordinarily no danger to employees is to be anticipated from such a trench asthat in question. The fact that the walls had maintained themselves for a week, without indicationof their giving way, strongly indicates that the necessity for bracing or shoring the trench wasremote. To require the company to guard against such an accident as the one in question wouldvirtually compel it to shore up every foot of the miles of trenches dug by it in the city of Manila forthe gas mains. Upon a full consideration of the evidence, we are clearly of the opinion thatordinary care did not require the shoring of the trench walls at the place where the deceased methis death. The event properly comes within the class of those which could not be foreseen;and, therefore, the defendant is not liable under the Civil Code (Article 1105, Civil Code). 2. Yes. Act No. 1874 is essentially a copy of the Massachusetts Employers' Liability Act. We nowcome to the consideration of Act No. 1874 for the purpose of determining what effect this Act hashad upon the law of damages in personal injury cases in this country, bearing in mind that theAct is, as we have indicated, essentially a copy of the Massachusetts Employers' Liability Actwhich has "prevailed in the State of Massachusetts some years and upon which interpretationshave been made by the Massachusetts courts, defining the exact meaning of the provision of thelaw." (Special report of the joint committee of the Philippine Legislature on the Employers'Liability Act, Commission Journal 1908, p. 296.) We agree with the Supreme Court ofMassachusetts that the Act should be liberally construed in favor of employees. The mainpurpose of the Act, as its title indicates, was to extend the liability of employers and to renderthem liable in damages for certain classes of personal injuries for which it was thought they wereliable under the law prior to the passage of the Act.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Possession DigestsDokument22 SeitenPossession DigestsKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Possession DigestsDokument22 SeitenPossession DigestsKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- PHYSICS Engineering (BTech/BE) 1st First Year Notes, Books, Ebook - Free PDF DownloadDokument205 SeitenPHYSICS Engineering (BTech/BE) 1st First Year Notes, Books, Ebook - Free PDF DownloadVinnie Singh100% (2)

- Safety Manual For CostructionDokument25 SeitenSafety Manual For CostructionKarthikNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIR Organizational StructureDokument1 SeiteBIR Organizational StructureKayeCie RL100% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDokument7 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- (With Exclusions) - LABOR-Case Digest CompendiumDokument221 Seiten(With Exclusions) - LABOR-Case Digest CompendiumAlyssa Mae Basallo100% (1)

- Part 1 Case Digest of Labor StandardsDokument238 SeitenPart 1 Case Digest of Labor StandardsMoe Barrios75% (20)

- LaborDokument8 SeitenLaborLizzy WayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Case 1 Maximo CalalangDokument9 SeitenLabor Case 1 Maximo CalalangboomboomdiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Law Cases First Set SUMMER 2015Dokument27 SeitenAdministrative Law Cases First Set SUMMER 2015Hv EstokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law 1 - Calalang v. Williams GR No. 47800 02 Dec 1940 70 Phil 727 SC Full TextDokument5 SeitenLabor Law 1 - Calalang v. Williams GR No. 47800 02 Dec 1940 70 Phil 727 SC Full TextJOHAYNIENoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang Vs WilliamsDokument3 SeitenCalalang Vs WilliamsLily CallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang v. Williams, G.R. No. 47800 December 02, 1940Dokument4 SeitenCalalang v. Williams, G.R. No. 47800 December 02, 1940Tin SagmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- LABOR 1 - June 26, 2017Dokument29 SeitenLABOR 1 - June 26, 2017Ratani UnfriendlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- LABOR 1 Cases - June 26, 2017Dokument29 SeitenLABOR 1 Cases - June 26, 2017Ratani UnfriendlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, vs. A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., RespondentsDokument6 SeitenMAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, vs. A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., RespondentsKennethAnthonyMagdamitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang vs. WilliamsDokument6 SeitenCalalang vs. Williams071409Noch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs Vera ReyesDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs Vera ReyesNolaida AguirreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang v. WilliamsDokument5 SeitenCalalang v. WilliamsHannah Plamiano TomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases For Labor Law ReviewDokument165 SeitenCases For Labor Law ReviewVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 People Vs Vera ReyesDokument2 Seiten3 People Vs Vera ReyesRonnie RimandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 47800 December 2, 1940 MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., Respondents. Decision Laurel, J.: Facts of The CaseDokument7 SeitenG.R. No. 47800 December 2, 1940 MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., Respondents. Decision Laurel, J.: Facts of The CaseBesprenPaoloSpiritfmLucenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 47800 December 2, 1940 MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., Respondents. Decision Laurel, J.: Facts of The CaseDokument7 SeitenG.R. No. 47800 December 2, 1940 MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, A. D. WILLIAMS, ET AL., Respondents. Decision Laurel, J.: Facts of The CaseBesprenPaoloSpiritfmLucenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Reyes, G.R. No. 45748, April 5, 1939Dokument2 SeitenPeople v. Reyes, G.R. No. 45748, April 5, 1939Regina ArahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court First Division: PetitionerDokument7 SeitenSupreme Court First Division: PetitionerMandy CayangaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CONSTI2Dokument278 SeitenCONSTI2Graziella AndayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6-12 Calalang vs. Williams, 70 Phil. 726 (1940)Dokument14 Seiten6-12 Calalang vs. Williams, 70 Phil. 726 (1940)Reginald Dwight FloridoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang v. WilliamsDokument3 SeitenCalalang v. WilliamsGem AusteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Cases CompilationDokument34 SeitenAdmin Cases CompilationBenn DegusmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang V WilliamsDokument2 SeitenCalalang V WilliamsshezeharadeyahoocomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Relations Cases IDokument24 SeitenLabor Relations Cases IBelle FabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang Vs WilliamsDokument4 SeitenCalalang Vs WilliamsGeorge PandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Digest 1-6Dokument12 SeitenLabor Digest 1-6Ron AceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, vs. A. D. WILLIAMS, ET: AL., RespondentsDokument70 SeitenMAXIMO CALALANG, Petitioner, vs. A. D. WILLIAMS, ET: AL., RespondentsPio Vincent BuencaminoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Justice: Calalang vs. WilliamsDokument7 SeitenSocial Justice: Calalang vs. WilliamsThea Pabillore100% (1)

- 01 Calalang vs. Williams FlowDokument5 Seiten01 Calalang vs. Williams FlowNichole LanuzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases For FinalsDokument20 SeitenCases For FinalsyjadeleonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Justice - Calalang v. Williams Et Al., 70 Phil., 726 (1940)Dokument2 SeitenSocial Justice - Calalang v. Williams Et Al., 70 Phil., 726 (1940)Aldin Limpao OsopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ccd-Llaw1 (C)Dokument220 SeitenCcd-Llaw1 (C)1AANoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang vs. WilliamsDokument10 SeitenCalalang vs. WilliamsRein SibayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang v. Williams, 70 Phil 726Dokument6 SeitenCalalang v. Williams, 70 Phil 726Kristanne Louise YuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Labor CasesDokument383 SeitenFinal Labor CasesAlianna Arnica MambataoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAXIMO CALALANG Vs A. D. WILLIAMSDokument14 SeitenMAXIMO CALALANG Vs A. D. WILLIAMSryuseiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3calalang Vs Ad WilliamsDokument2 Seiten3calalang Vs Ad WilliamsJohn AmbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CALALANG Vs WILLIAMSDokument5 SeitenCALALANG Vs WILLIAMSAlvin SamonteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax 1 Case DigestsDokument5 SeitenTax 1 Case DigestsMarinel RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carlos vs. VillegasDokument2 SeitenCarlos vs. VillegasJaneen ZamudioNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1940 Calalang - v. - Williams20160213 374 A4cmdg PDFDokument6 Seiten1940 Calalang - v. - Williams20160213 374 A4cmdg PDFChristian VillarNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Vs Tang Ho Case DigestDokument6 SeitenUS Vs Tang Ho Case DigestArgel Joseph CosmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang V WilliamsDokument1 SeiteCalalang V WilliamsCzar Ian AgbayaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- MAXIMO CALALANG Vs A.D. WILLIAMS ET ALDokument8 SeitenMAXIMO CALALANG Vs A.D. WILLIAMS ET ALCharles Roger RayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consti ReviewerDokument39 SeitenConsti ReviewernellafayericoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Vera Reyes, G.R. No. L-45748, April 5, 1939Dokument1 SeitePeople v. Vera Reyes, G.R. No. L-45748, April 5, 1939Digests LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. Vera Reyes G..R. NO. L-45748 APRIL 5, 1939 Imperial, J. FactsDokument2 SeitenPeople vs. Vera Reyes G..R. NO. L-45748 APRIL 5, 1939 Imperial, J. FactsJustin Luis JalandoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalang Vs WilliamsGR 47800 December 2Dokument5 SeitenCalalang Vs WilliamsGR 47800 December 2tere_aquinoluna828Noch keine Bewertungen

- Federal Constitution of the United States of MexicoVon EverandFederal Constitution of the United States of MexicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeVon EverandPatent Laws of the Republic of Hawaii and Rules of Practice in the Patent OfficeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Review Companion: Labor Laws and Social Legislation: Anvil Law Books Series, #3Von EverandBar Review Companion: Labor Laws and Social Legislation: Anvil Law Books Series, #3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Selected Official Documents of the South African Republic and Great Britain: A Documentary Perspective Of The Causes Of The War In South AfricaVon EverandSelected Official Documents of the South African Republic and Great Britain: A Documentary Perspective Of The Causes Of The War In South AfricaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AM No. 18-03-16-SCDokument7 SeitenAM No. 18-03-16-SCKayeCie RL100% (1)

- Honda Recalls Another 4Dokument4 SeitenHonda Recalls Another 4KayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- JURIS Antichresis MortgageDokument2 SeitenJURIS Antichresis MortgageKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brandir International v. CascadeDokument9 SeitenBrandir International v. CascadeKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Childress v. TaylorDokument10 SeitenChildress v. TaylorKayeCie RL100% (1)

- Americaonline V.albaneseDokument4 SeitenAmericaonline V.albaneseKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carpio-Morales Case Digests in Taxation LawDokument6 SeitenCarpio-Morales Case Digests in Taxation Laweneri_Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dept. Order No. 9Dokument50 SeitenDept. Order No. 9KayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cir V Court of Appeals: San Beda College of Law - CLASS 3C-2010-2011Dokument47 SeitenCir V Court of Appeals: San Beda College of Law - CLASS 3C-2010-2011KayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tariff & Customs Code Vol 1Dokument47 SeitenTariff & Customs Code Vol 1cmv mendoza100% (14)

- Corpo Cases 1Dokument251 SeitenCorpo Cases 1KayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 - Petition For Authority To Continue Use of The Firm NameDokument2 Seiten12 - Petition For Authority To Continue Use of The Firm NameKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Memo LegOp Lecture Notes Judge Serrano Lecture With SamplesDokument16 SeitenMemo LegOp Lecture Notes Judge Serrano Lecture With SamplesKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Director of Lands vs. AbelardoDokument1 SeiteDirector of Lands vs. AbelardoKayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 - Reyes Vs Gaa (Pale)Dokument1 Seite11 - Reyes Vs Gaa (Pale)KayeCie RLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitution Project .1Dokument10 SeitenConstitution Project .1gavneet singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kerala Land Assignment Act - James Joseph Adhikarathil Realutionz - Your Property Problem Solver 9447464502Dokument57 SeitenKerala Land Assignment Act - James Joseph Adhikarathil Realutionz - Your Property Problem Solver 9447464502James Joseph AdhikarathilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art. 1323-1330 GAWDokument3 SeitenArt. 1323-1330 GAWChris Gaw100% (1)

- 2020 Stetson IEMCC Clarifications PDFDokument2 Seiten2020 Stetson IEMCC Clarifications PDFCocoy LicarosNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIRC Rem NotesDokument15 SeitenNIRC Rem NotesSherwin LingatingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceniza V Neri 3Dokument5 SeitenCeniza V Neri 3Michael Kevin MangaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper 1: Forensic Science: Unit-IDokument7 SeitenPaper 1: Forensic Science: Unit-IArun GautamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dirtshield 12 - DCM-APR FX 18PVC GlossDokument2 SeitenDirtshield 12 - DCM-APR FX 18PVC GlossMuhammad Anwer100% (1)

- (GR) JM Tuason V Vda de Lumanlan (1968)Dokument5 Seiten(GR) JM Tuason V Vda de Lumanlan (1968)Jethro KoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gaseous StateDokument51 SeitenGaseous StateSal Sabeela RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bonds - Forms & Precedents - Raymond WaltonDokument27 SeitenBonds - Forms & Precedents - Raymond WaltonAmis Nomer100% (3)

- Land ConversionDokument17 SeitenLand ConversionjayrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deed of Undertaking - NewDokument6 SeitenDeed of Undertaking - NewHanna Mae GabrielNoch keine Bewertungen

- STRS Class Action ComplaintDokument16 SeitenSTRS Class Action ComplaintFinney Law Firm, LLCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law II SyllabusDokument19 SeitenCriminal Law II SyllabusJaime Rariza Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Socrates vs. COMELECDokument3 SeitenSocrates vs. COMELECKristine JoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comelec Group 2Dokument26 SeitenComelec Group 2Kenshin Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- UCSPDokument3 SeitenUCSPQueenie Trett Remo MaculaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Form 13A (Request For Availability of Name)Dokument2 SeitenForm 13A (Request For Availability of Name)Zaim Adli100% (1)

- La Draft DocumentDokument2 SeitenLa Draft DocumentDeepak_pethkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- $100 No Deposit Bonus Terms and Conditions: Traders Capital Limited (Herein "Company") Operating Under Trading Name TTCMDokument4 Seiten$100 No Deposit Bonus Terms and Conditions: Traders Capital Limited (Herein "Company") Operating Under Trading Name TTCMSyed IzliNoch keine Bewertungen

- NTPC Limited: Biennial Contract For Monthly Topographical Survey Work For Physical Coal Stock Verification in CHP AreaDokument4 SeitenNTPC Limited: Biennial Contract For Monthly Topographical Survey Work For Physical Coal Stock Verification in CHP AreaMANISH KAPADIYANoch keine Bewertungen

- Maricel Soriano - SM HypermarketDokument2 SeitenMaricel Soriano - SM HypermarketEric SarmientoNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOLE vs. MaritimeDokument2 SeitenDOLE vs. MaritimesoulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lea 1 2023 Post TestDokument6 SeitenLea 1 2023 Post TestHan WinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macasiano vs. Diokno, G.R. No. 97764, August 10, 1992 - Full TextDokument8 SeitenMacasiano vs. Diokno, G.R. No. 97764, August 10, 1992 - Full TextMarianne Hope VillasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLS Aipmt 15 16 XI Che Study Package 2 SET 1 Chapter 5Dokument20 SeitenCLS Aipmt 15 16 XI Che Study Package 2 SET 1 Chapter 5sairaj67% (3)