Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Global Warming

Hochgeladen von

Peter WilliamsCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Global Warming

Hochgeladen von

Peter WilliamsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Greenhouse Effect As early as 1827, the French mathematician and engineer Josephe Fourier had theorised that

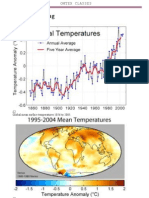

the earths atmosphere plays a crucial part in determining surface temperatures by trapping heat radiated by the sun, thus preventing it from escaping back into space. This greenhouse effect was crucial to the survival of life on earth because, without it, the global average temperature of around 15 degrees C. would drop to minus 18 degrees, creating an intense, world-wide ice age.18 In 1860 John Tyndall, the Irish physicist, reported that only certain gases in the atmosphere had this invaluable property. As the earth is heated by the sun, the commonest gases, nitrogen and oxygen, do not prevent this heat, in the form of infra-red radiation, escaping back into space. But the greenhouse gases do, thus retaining the suns heat. By far the most important of these greenhouse gases is water vapour, contributing around 95 percent of the greenhouse effect. This is followed by carbon dioxide, CO2 (3.62 percent); nitrous oxide (0.95 percent); methane (0.36 percent) and others, including CFCs, or chlorofluorocarbons, (0.07 percent). In 1938, inspired by the rapidly rising temperatures of the 1920s and 1930s, a British meteorologist Guy Callendar suggested that the cause of this rise might be the marked increase in the burning of coal and oil in the age of mass-industrialisation, electricity and the motor car. Far from seeing this as an unqualified disaster, however, he saw it a beneficial to mankind; not least in allowing for greater agricultural production. It might even hold off the return of a new ice age indefinitely. 20 What Callendar was recognising, of course, was that although CO2 makes up only a minuscule proportion of all the gases in the earths atmosphere compared with nitrogen, oxygen and the rest it represents a mere 0.04 percent of the total it plays an absolutely vital role in the survival of life. Of the estimated 186 billion tons of CO2 which enter our atmosphere each year from all sources, only 3.3 percent comes from human activity. More than 100 billion tons (57 percent) is given off by the oceans. 71 billion tons (38 percent) is breathed out by animals, including ourselves. And on that supply of CO2 depends the survival of the entire plant kingdom, without which the rest of life could not exist. Trees and all other plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, transforming it by photosynthesis into the oxygen essential to all animal life. And, as Callendar was aware, an increase in CO2 serves to promote plant growth, which was why he foresaw a higher CO2 level as likely to boost human food production. Scarcely had Callendar made his prediction, however, than the Little Cooling arrived. As temperatures began dropping again, there now seemed little immediate cause for concern over global warming. But the essence of what he and Arrhenius had been on about was not forgotten. This was particularly true when the 1960s saw the rise of the modern environmentalist movement, rooted in a conviction that mans reckless greed in despoiling the planet was threatening to disturb the balance of nature to such an extent that the very survival of life was in doubt. Even at the height of that 1970s panic over a new ice age, the article cited earlier from the Science Digest ended by quoting two geologists that mans tampering with the environment might lead to the opposite effect: a

global heatwave caused by an excess of carbon dioxide emissions. Through the so-called greenhouse effect, they said, this could lead to such a rise in temperatures that the nine million cubic miles of ice covering Greenland and the Antarctic would melt. The worlds sea levels would be raised to such an extent that every coastal city would be flooded. When, shortly afterwards, measurements showed surface temperatures sharply rising again, all might have seemed set for a revival of the belief that the ever-increasing emissions of CO2 resulting from human exploitation of the planets resources were about to lead to a wholly unnatural and potentially catastrophic degree of global warming. This belief was reinforced by the findings of a team of American scientists who, for more than 20 years, had been systematically recording the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere from a weather station on top of a Hawaiian volcano, Mauna Loa. Dr Roger Revelle of the University of Californias Scripps Institution of Oceanography was an outstanding scientist in his field. He and his colleagues were well aware that, as part of the earths climatic regulatory system, the oceans not only give out a huge amount of carbon dioxide but also absorb it from the air above them, By concentrating their attention on CO2 and other manmade contributions to greenhouse gas, they had tended to overlook or to misjudge the part played by far the most important greenhouse gas of all, water vapour, comprising all but a tiny fraction of the total. They had also failed to allow for the negative feedback effect of cloud-cover. 26 In both these respects, the computer models had neither the physics nor the numerical accuracy to come up with findings which were not disturbingly arbitrary. Put these two factors properly into the equation, argued Lindzen, and it could be seen that the greenhouse effect caused by rising CO2 levels had been wildly overstated. What was more, this could be demonstrated by running those same computer models retrospectively, to predict where temperatures should have been throughout the 20 th century. It became glaringly obvious that these over-simplified programmes failed to explain the actual variations which had taken place in 20 th century temperature levels. In the 1920s and 1930s, when greenhouse gas emissions were comparatively low, temperatures had sharply risen,. But in the very years when emissions were rising most steeply, during the Little Cooling between the 1940s and the 1970s, temperatures were in decline. In fact the assumptions on which the models were based would have led them to predict a 20th century warming four times greater than the rise that had been actually recorded (with most of that rise taking place before atmospheric CO2 had reached anything like its present level). On this basis, how could any trust now be placed in their attempts to estimate future rises? Clearly some significant factors were getting missed out by the modellers as they made their extravagant predictions of future warming. But the campaigners were already becoming distinctly impatient with climate sceptics, such as Lindzen, who dared question their thesis. They were attacked in books and in a long article in the New York Times by Senator Gore, who compared true believers such as himself to Galileo, bravely standing for the truth against the blind orthodoxy of his time. And in 1990 the global warming advocates won their most powerful support of all when the UNs Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change produced its First

Assessment Report (FAR). Over the years ahead the IPCC, through a succession of such reports, was to become the central player in the debate. As this initial report exemplified, these emerged from an elaborate two-stage process. The first involved compiling a three-part scientific report, under the main headings of the IPCCs agenda: assessment of climate change, assessment of its impact and recommendations for action. This technical report was compiled by three working groups, made up of many different scientists, economists a nd experts of every kind. These authors contributed to a series of chapters, under the guidance of lead authors and a lead chapter author. The resulting draft was then circulated to hundreds of expert reviewers throughout the world for comment.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth’s ClimateVon EverandThe Long Thaw: How Humans Are Changing the Next 100,000 Years of Earth’s ClimateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Report On Global WarmingDokument45 SeitenTechnical Report On Global WarmingRahul Kumar70% (10)

- The Human Planet: How We Created the AnthropoceneVon EverandThe Human Planet: How We Created the AnthropoceneBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- ParaprosdokianDokument2 SeitenParaprosdokianPeter WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dry Docking QuotationDokument4 SeitenDry Docking Quotationboen jayme100% (1)

- M 3 Nceog 2Dokument110 SeitenM 3 Nceog 2Bharti SinghalNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2005.02.12. New Scientist. Climate ChangeDokument5 Seiten2005.02.12. New Scientist. Climate ChangeSteven RogersNoch keine Bewertungen

- eenhouseOrIceAge #D314Dokument2 SeiteneenhouseOrIceAge #D314boninhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Climate ChangeDokument55 SeitenUnderstanding Climate Changeasofyan2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change HistoryDokument11 SeitenClimate Change HistoryNikiki ElababajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Compulsory MaterialDokument8 SeitenEnglish Compulsory MaterialMaryam ZaidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leading To Urban Heat Islands As Much As 12°C Hotter Than Their SurroundingsDokument1 SeiteLeading To Urban Heat Islands As Much As 12°C Hotter Than Their SurroundingsAmerigo VespucciNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Realization of Global WarmingDokument5 SeitenThe Realization of Global WarmingFaris HamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Index: If There Are Images in This Attachment, They Will Not Be Displayed. Download TheDokument14 SeitenIndex: If There Are Images in This Attachment, They Will Not Be Displayed. Download TheAffNeg.ComNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading MaterialDokument3 SeitenReading Materialperezcarlj1010Noch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: 50 tips about the hot topic many people dismissVon EverandGlobal Warming: 50 tips about the hot topic many people dismissNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Global Warming Affected PeopleDokument5 SeitenHow Global Warming Affected PeopleAlthea Dennise Dela PeñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Global Warming Is A HoaxDokument11 SeitenWhy Global Warming Is A Hoaxme n myself100% (1)

- 3.13 Why Is There Debate On Climate Change Independent IntroDokument5 Seiten3.13 Why Is There Debate On Climate Change Independent IntroHoly JesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill Mckibben A Very Hot Year NyrbDokument7 SeitenBill Mckibben A Very Hot Year NyrbNoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLIMATE CHANGE: Facts, Details and OpinionsDokument8 SeitenCLIMATE CHANGE: Facts, Details and OpinionsMona VimlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Hyperlinked History of Climate Change ScienceDokument7 SeitenA Hyperlinked History of Climate Change SciencedanieldiazmontoyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Iv Climate ChangeDokument35 SeitenChapter Iv Climate ChangeAminus SholihinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Robinson and RobinsonDokument4 SeitenRobinson and RobinsonHennerre AntipasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Long Hot Year: Latest Science Debunks Global Warming Hysteria, Cato Policy AnalysisDokument16 SeitenLong Hot Year: Latest Science Debunks Global Warming Hysteria, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: Mukesh Kumar, Adnan Zubair Ashwani Anand, Md. ImranDokument12 SeitenGlobal Warming: Mukesh Kumar, Adnan Zubair Ashwani Anand, Md. ImranVivek KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief History of Global Climate ChnageDokument15 SeitenA Brief History of Global Climate ChnageRozi AmjedNoch keine Bewertungen

- English PDFDokument18 SeitenEnglish PDFManikandanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global WarmingDokument13 SeitenGlobal WarmingYagnik Mhatre50% (4)

- BlameDokument4 SeitenBlamesharon gillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final ProjectDokument22 SeitenFinal ProjectritanarkhedeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical Report On Global Warming: Submitted byDokument45 SeitenTechnical Report On Global Warming: Submitted bychirag yadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Global Warming and Climate Change?: EffectDokument23 SeitenWhat Is Global Warming and Climate Change?: Effectmitalidutta2009100% (1)

- Climate Change FactsDokument51 SeitenClimate Change FactsRam Eman OsorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Realistic Look at Global WarmingDokument4 SeitenA Realistic Look at Global Warmingeustoque2668Noch keine Bewertungen

- Climate ChangeDokument20 SeitenClimate ChangeSapnatajbarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: An IntroductionDokument13 SeitenGlobal Warming: An IntroductionSunit SahuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Global Warming A ThreatDokument5 SeitenIs Global Warming A ThreatErin ParkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: Omtex ClassesDokument11 SeitenGlobal Warming: Omtex ClassesAMIN BUHARI ABDUL KHADERNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming EssayDokument9 SeitenGlobal Warming EssayAtifqaisraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicole ReportDokument11 SeitenNicole ReportDesiree Tenorio VillezaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global WarmingDokument4 SeitenGlobal WarmingWahdat HasaandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming Global Warming, The Phenomenon of Increasing Average Air Temperatures Near TheDokument7 SeitenGlobal Warming Global Warming, The Phenomenon of Increasing Average Air Temperatures Near TheOSWALDO KENKY KENYO ESTRADA PACHERRESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming (New)Dokument17 SeitenGlobal Warming (New)AMIN BUHARI ABDUL KHADER100% (1)

- 2010 Was The Warmest Year On Record': ScarewatchDokument7 Seiten2010 Was The Warmest Year On Record': Scarewatchapi-51541764Noch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming ThesisDokument15 SeitenGlobal Warming ThesisSaira Caritan100% (1)

- What Is Climate Change?Dokument27 SeitenWhat Is Climate Change?Basit SaeedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming: An IntroductionDokument16 SeitenGlobal Warming: An IntroductionNeha NigamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rechauffement ClimatiqueDokument8 SeitenRechauffement Climatiquedosso levyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of Global WarmingDokument6 SeitenEffect of Global Warmingdhiren100% (1)

- Revised Research Essay 4 1Dokument11 SeitenRevised Research Essay 4 1api-608875092Noch keine Bewertungen

- Topic B: Global Climate ChangeDokument5 SeitenTopic B: Global Climate ChangeIvan CabroneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition For Global WarmingDokument4 SeitenDefinition For Global Warmingdeep932Noch keine Bewertungen

- Crash Course On Climate ChangeDokument12 SeitenCrash Course On Climate Changeapi-511260715Noch keine Bewertungen

- Global Warming and Climate ChangeDokument10 SeitenGlobal Warming and Climate ChangeMuhammad WaseemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global WarmingDokument13 SeitenGlobal WarmingRam KrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global WarmingDokument10 SeitenGlobal Warmingtusharbooks100% (34)

- University of Duhok College of Engineering Surveying DepartmentDokument34 SeitenUniversity of Duhok College of Engineering Surveying DepartmentAlan ArifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Vapor, Not Carbon Dioxide, Is Major Contributor to the Earth's Greenhouse Effect: Putting the Kibosh on Global Warming AlarmistsVon EverandWater Vapor, Not Carbon Dioxide, Is Major Contributor to the Earth's Greenhouse Effect: Putting the Kibosh on Global Warming AlarmistsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vanishing Peaks: Unveiling the Impact of Climate Change on Global SnowpacksVon EverandVanishing Peaks: Unveiling the Impact of Climate Change on Global SnowpacksNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Bush/Blair Legacy - Tarnished TinDokument1 SeiteOn The Bush/Blair Legacy - Tarnished TinPeter WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crime and PunishmentDokument3 SeitenCrime and PunishmentPeter WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art of Body Spirit Healing by Peter WilliamsDokument17 SeitenArt of Body Spirit Healing by Peter WilliamsvirendhemreNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of ErpDokument2 SeitenList of Erpnavyug vidyapeeth trust mahadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Socratic Pluralism AtomismDokument1 SeitePre-Socratic Pluralism AtomismpresjmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Project Part-3 Marketing PlanDokument8 SeitenFinal Project Part-3 Marketing PlanIam TwinStormsNoch keine Bewertungen

- ns2 LectureDokument34 Seitenns2 LecturedhurgadeviNoch keine Bewertungen

- N Mon Visualizer OverviewDokument27 SeitenN Mon Visualizer OverviewClaudioQuinterosCarreñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perfil Clinico de Pacientes Con Trastornos de La Conducta AlimentariaDokument44 SeitenPerfil Clinico de Pacientes Con Trastornos de La Conducta AlimentariaFrida PandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learn To Write Chapter 1 ProposalDokument52 SeitenLearn To Write Chapter 1 Proposalrozaimihlp23Noch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5, Orders and Cover Letters of Orders For StsDokument13 SeitenUnit 5, Orders and Cover Letters of Orders For StsthuhienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Technical EnglishDokument7 SeitenTechnical EnglishGul HaiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Graphs in ChemDokument10 SeitenGraphs in Chemzhaney0625Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gunnar Fischer's Work On Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal and Wild StrawberriesDokument6 SeitenGunnar Fischer's Work On Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal and Wild StrawberriesSaso Dimoski100% (1)

- Culture NegotiationsDokument17 SeitenCulture NegotiationsShikha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helena HelsenDokument2 SeitenHelena HelsenragastrmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purchase Spec. For Bar (SB425)Dokument4 SeitenPurchase Spec. For Bar (SB425)Daison PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission Prspectus English 2021-2022Dokument9 SeitenAdmission Prspectus English 2021-2022A.B. SiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ESUR Guidelines 10.0 Final VersionDokument46 SeitenESUR Guidelines 10.0 Final Versionkon shireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Far Eastern University Mba - Thesis 060517Dokument2 SeitenFar Eastern University Mba - Thesis 060517Lex AcadsNoch keine Bewertungen

- B2 UNIT 6 Test StandardDokument6 SeitenB2 UNIT 6 Test StandardКоваленко КатяNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brochure Delegation Training For LeadersDokument6 SeitenBrochure Delegation Training For LeadersSupport ALProgramsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Upsa Y5 2023Dokument8 SeitenUpsa Y5 2023Faizal AzrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cottrell Park Golf Club 710Dokument11 SeitenCottrell Park Golf Club 710Mulligan PlusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entropy (Information Theory)Dokument17 SeitenEntropy (Information Theory)joseph676Noch keine Bewertungen

- Former Rajya Sabha MP Ajay Sancheti Appeals Finance Minister To Create New Laws To Regulate Cryptocurrency MarketDokument3 SeitenFormer Rajya Sabha MP Ajay Sancheti Appeals Finance Minister To Create New Laws To Regulate Cryptocurrency MarketNation NextNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 2 Management Perspective Son Leadership MotivationDokument14 SeitenAssignment 2 Management Perspective Son Leadership MotivationHoneyVasudevNoch keine Bewertungen

- RULE 130 Rules of CourtDokument141 SeitenRULE 130 Rules of CourtalotcepilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kibera Mirror JULYDokument8 SeitenKibera Mirror JULYvincent achuka maisibaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daftar PustakaDokument1 SeiteDaftar PustakaUlul Azmi Rumalutur NeinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- D1 001 Prof Rudi STAR - DM in Indonesia - From Theory To The Real WorldDokument37 SeitenD1 001 Prof Rudi STAR - DM in Indonesia - From Theory To The Real WorldNovietha Lia FarizymelinNoch keine Bewertungen