Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Coumadin Necrosis

Hochgeladen von

philsguOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Coumadin Necrosis

Hochgeladen von

philsguCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Case Report

Warfarin-Induced Skin Necrosis

Donald W. Alves, MD

Ian A. Chen, MD

ral anticoagulation therapy with warfarin may with an ejection fraction of approximately 58% and no

O cause injury to the skin. Cutaneous injury

from warfarin begins as localized paresthesias

with an erythematous flush, progresses to

petechiae and hemorrhagic bullae, and may eventually

result in full-thickness skin necrosis. Patients typically

vegetations. Results of an upper-extremity ultrasono-

graphic examination were normal, and a Doppler

examination of the carotid arteries showed only mini-

mal changes, bilaterally. A venous duplex ultrasono-

graphic examination of both lower extremities revealed

experience pain in affected areas. The onset of disease acute right sural and peroneal vein thromboses (ie,

is usually between the third and sixth day of therapy. deep venous thromboses [DVTs]), which supported the

Early recognition and treatment are important to avoid decision to administer heparin to the patient.

substantial morbidity. This article describes the clinical Heparin therapy. Heparin was administered by

course of a patient who developed warfarin-induced using our institution’s protocol of 5000 U administered

skin necrosis (WISN) and discusses the clinical mani- via intravenous bolus, followed immediately by mainte-

festations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of this nance therapy involving the continuous intravenous

condition. infusion of heparin at an initial rate of 1000 U/h.

According to the protocol, adjustments to the infusion

CASE PRESENTATION rate are to be made every 6 hours, until the partial

Emergency Department Evaluation thromboplastin time (PTT) reaches the therapeutic

A 73-year-old woman with a history of hyperten- range; the PTT is in the therapeutic range when it is

sion, glaucoma, and heavy tobacco abuse was brought approximately 2 times the control value.

to the emergency department after being found lying The patient had a difficult course after the initiation

on the floor semiconscious at home. Chest radiogra- of heparin therapy. Because she could not be weaned

phy revealed right middle/lower lobe pneumonia. from the ventilator, a tracheostomy with concurrent per-

Further evaluation revealed atrial fibrillation with a cutaneous gastrostomy was performed. During the next

rapid ventricular response, temperature of 40.2°C few days, the patient’s mental status improved; however,

(104.3°F), leukocyte count of 28.4 × 103/mm3, mild she continued to be dependent on the ventilator.

respiratory distress, and altered mental status. These Warfarin therapy. By the ninth hospital day, the pa-

findings were subsequently attributed to pneumococ- tient continued to have intermittent atrial fibrillation.

cal meningitis after culture of cerebrospinal fluid. She The atrial fibrillation, the lower extremity DVTs, and

was treated with oxygen, intravenous hydration thera- her long-term confinement to bed prompted a deci-

py, antibiotic drugs, and heparin, and she was admitted sion to convert the heparin to warfarin; after the war-

to the hospital for further evaluation and treatment. farin took effect, the heparin was to be discontinued.

The patient initially received 5 mg of warfarin, orally,

Hospital Course each evening for 2 days, and the dose was decreased to

Because of decreasing PaO2, despite the administra- 4 mg the third evening after an initial increase in her

tion of 100% oxygen, the patient was urgently intubated international normalized ratio (INR), from 1.0 to 1.6.

for ventilatory support during her first day in the hospi- Our target for the INR was 2.0 to 2.5 times the control

tal. The neurology department was consulted for assis- value. However, the following morning, the patient’s

tance with the management of her meningitis after she

began to experience seizures and left-sided flaccidity.

Diagnostic studies. An electroencephalogram re-

Dr. Alves is a Clinical Instructor and Emergency Medical Services Fellow,

vealed generalized slowing, secondary to nonspecific Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Maryland Medical

encephalopathy, but no seizure activity. An echocardio- Center, Baltimore, MD. Dr. Chen is an Assistant Professor, Department of

gram showed moderate-to-severe aortic regurgitation Internal Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA.

www.turner-white.com Hospital Physician August 2002 39

Alves & Chen : War farin -Induced Skin Necrosis : pp. 39 – 42

Further treatment. The patient was given 10 mg of vit-

amin K, intravenously, and 2 U of fresh frozen plasma

(FFP) to reverse the effects of the warfarin.1 She was also

given 15,000 U of heparin via intravenous bolus, and

continuous heparin infusion therapy was reinstituted to

prevent hypercoagulability. The maintenance dosage of

the heparin was set according to a weight-based regi-

men, to rapidly increase the PTT to 2 to 3 times the con-

trol value.2 Subsequently, the patient bled superficially at

her tracheostomy site (< 200 mL), and the bleeding was

controlled with direct pressure. The patient was given an

A additional 5 mg of vitamin K, intravenously. The heparin

infusion was discontinued, and a third unit of FFP was

administered. No further bleeding occurred. A dissemi-

nated intravascular coagulopathy panel was negative,

and the patient’s mental status did not deteriorate.

Wound care. Local wound care was provided to pre-

vent bullae rupture, and low-molecular-weight hep-

arin was administered, subcutaneously, for DVT pro-

phylaxis. The bullae fluid, which was cultured at the

request of an infectious disease consultant, was nega-

tive for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, acid-fast bacilli,

and fungi. Consultation with a dermatologist con-

firmed that the lesions were consistent with WISN, and

the dermatologist agreed with the plan of local wound

B care pending a determination of the severity of the pa-

tient’s condition and future definitive care.

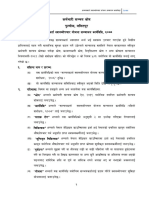

Figure 1. (A) An erythematous skin lesion, approximately

To improve our understanding of the spectrum of

15 cm by 10 cm, on the case patient’s right hip. (B) A similar

tissue damage associated with WISN, the dermatologist

lesion on the patient’s left thigh.

equated the spectrum to that observed with partial to

full-thickness burns and used a grading scale common-

ly used with decubitus ulcers (grade I to IV). However,

INR was greater than 5.6 on repeat analysis, and the the consultant did not know of any formal grading

warfarin was withheld. The INR remained greater scale for WISN.

than 5.4 for 2 days after the warfarin was stopped; at Patient outcome. The intensity of pain experienced

that time, the heparin infusion was also discontinued. by the patient rapidly decreased during the next 3 or

The heparin infusion had previously been maintained 4 days after the start of the wound care, and the skin

with therapeutic PTTs, without difficulty. lesions matured quickly. There was some increase in

Skin lesions. By the sixth day after warfarin had the size of the bullae and only superficial sloughing

first been administered, an erythematous skin lesion, (grade I) in the areas that had encompassed the bullae,

approximately 15 cm by 10 cm, was noted on the pa- leaving clean, well-demarcated margins, with serosan-

tient’s right hip and a similar one was noted on her guinous crusting and granulation tissue at the bases. By

left thigh (Figure 1); the patient reported intense this time, the sizes of the lesions on her legs were as fol-

localized pain bilaterally. An initial concern regard- lows: right leg, 1.5 × 2.5 cm; left leg, 6 × 8 cm. The

ing a possible decubitus variant was dismissed patient was subsequently transferred to a long-term

because of the lesions’ presence in non–weight - ventilator facility with ongoing local wound care consist-

bearing locations, as well as the skin-protective air ing of daily dressing changes and topical antibiotic oint-

mattress used by the patient, peau d’orange skin ment application.

changes, intense pain, and development of ecchymo-

sis and bullae within the lesions within 6 hours. A lit- DISCUSSION

erature search was performed for treatment recom- According to our literature review, skin necrosis

mendations. occurs in 0.01% to 0.1% of patients receiving warfarin,

40 Hospital Physician August 2002 www.turner-white.com

Alves & Chen : War farin -Induced Skin Necrosis : pp. 39 – 42

orally.3 It is more common among middle-aged, peri- Table 1. Differential Diagnosis of Skin Lesions in

menopausal, obese women being treated for DVTs or Patients Receiving Warfarin Therapy

pulmonary emboli.1,3 WISN has been postulated to be

associated with deficiencies of protein C, protein S, fac- Acute necrotizing fasciitis

tor VII, and antithrombin III.1,2,4 Also, there is a case Calciphylaxis (in patients undergoing renal dialysis)

report attributing WISN-like lesions to vitamin K defi- Cellulitis

ciency in the absence of warfarin therapy.5 Cryofibrinogenemia

Clinical Manifestations Decubitus ulcer

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy with purpura

Patients may initially experience local paresthesias

fulminans

with an erythematous flush that is not well demarcated,

followed by intense pain and the rapid development Ecthyma

and coalescence of petechiae, with concomitant accu- Fournier’s gangrene

mulation of subcutaneous edema resulting in a peau Hematoma

d’orange appearance. During the first 24 hours after Heparin-induced antiplatelet antibodies

the first sign of skin lesions, hemorrhagic bullae within Inflammatory breast cancer

the involved area may occur and signal irreversible tis-

Lupus anticoagulation–associated skin necrosis

sue injury. Full-thickness skin necrosis is the end stage

of cutaneous injury. Once the overlying eschar sloughs, Microembolization

the residual defect is revealed. The spectrum of tissue Purple toe cholesterol embolism syndrome

damage ranges from self-limited, superficial tissue loss Pyoderma gangrenosum

capable of healing by spontaneous granulation, to

injury requiring surgical débridement with skin graft-

ing, to extreme tissue sloughing and loss with extensive

deficits occasionally leading to amputation.1 neously or intravenously (depending on patient stabil-

Location of the lesions varies. However, in women, ity and the extent of skin involvement), and FFP, with

the breasts are the most common sites, followed by the the objective of restoring vitamin K–dependent coagu-

buttocks and thighs.1 In men, chest involvement is rare, lation factors depleted by warfarin therapy. Based on a

but sometimes the skin of the penis may be affected.1 In patient’s underlying pathology prompting anticoagula-

addition to these sites, the trunk, face, and extremities tion therapy, many clinicians also recommend resump-

may be involved in both men and women. tion or continuance of heparin therapy by using a

weight-based dosing protocol to maintain the PTT at

Diagnosis 2 to 3 times the control value. Newer short-term thera-

At initial presentation, the lesion(s) of WISN must pies include purified protein C concentrate, for pa-

be differentiated from several conditions, such as gan- tients who are deficient in the protein, and prostacy-

grene,1 decubitus ulcer,3 and a hematoma—a much clin, for which clinical and histologic improvements

more common complication of warfarin therapy.6 The have been reported.1

differential diagnosis of skin lesions in patients receiv- Long-term treatment includes local wound care

ing warfarin therapy is presented in Table 1. WISN is and observation of the wound for signs of granulation

usually diagnosed clinically, based on patient symptoms, tissue and healing. Some injuries require surgical dé-

lesion appearance, clues in the patient’s phenotype (eg, bridement with skin grafting. In severe cases, amputa-

obesity, short stature, stocky build), and history of tion may be necessary.

recent warfarin therapy. Approximately 83% to 90% of Some clinicians have reported the recurrence of

patients develop symptoms between days 3 and 6 of WISN in patients reintroduced to warfarin.2,3 Although

warfarin treatment.7 Although not required for diagno- such recurrence is rare, the cautious resumption of war-

sis, skin biopsy will often reveal subepidermal hemor- farin is recommended for patients with significant need

rhages with adjacent epidermal necrosis and conges- for anticoagulant therapy. Long-term (subcutaneous)

tion and thrombosis of superficial dermal capillaries.7 therapy with heparin is associated with osteoporosis and

thrombocytopenia, as well as a very rare skin necrosis

Treatment syndrome similar to WISN.7 Some clinicians suggest

Short-term treatment recommendations include fractionated (low-molecular-weight) heparin as a more

the use of vitamin K, administered either subcuta- conservative method of anticoagulation therapy.7

www.turner-white.com Hospital Physician August 2002 41

Alves & Chen : War farin -Induced Skin Necrosis : pp. 39 – 42

REFERENCES

Fractionated heparin has a more favorable adverse-

effects profile compared with unfractionated heparin.7 1. Chan YC, Valenti D, Mansfield AO, Stansby G. Warfarin

induced skin necrosis. Br J Surg 2000;87:266–72.

Prevention 2. Sallah S, Abdalah JM, Gagnon GA. Recurrent warfarin-

induced skin necrosis in kindreds with protein S defi-

Several recommendations for preventing WISN

ciency. Haemostasis 1998;28:25–30.

have been advanced: (1) heparin should be continued

3. Gelwix TJ, Beeson MS. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis.

until the INR is near the therapeutic range as a result Am J Emerg Med 1998;16:541–3.

of the warfarin therapy and vitamin K–dependent clot- 4. Goldfrank LR, editor. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergen-

ting factors have been consumed1 – 12; (2) standard or cies. 5th ed. Norwalk (CT): Appleton & Lange; 1994:617.

low-dose warfarin should be used instead of initial 5. Humphries JE, Gardner JH, Connelly JE. Warfarin skin

large loading-doses; and (3) a clinician should be cau- necrosis: recurrence in the absence of anticoagulant

tious when advancing the dosage of warfarin. therapy. Am J Hematol 1991;37:197–200.

In our patient, the heparin remained therapeutic 6. Stewart AJ, Penman ID, Cook MK, Ludlam CA. Warfarin-

during the initiation of warfarin therapy, and the induced skin necrosis. Postgrad Med J 1999;75:233–5.

heparin was discontinued after 2 days of an INR greater 7. Essex DW, Wynn SS, Jin DK. Late-onset warfarin-induced

than 5. The patient received a total of 14 mg of warfarin skin necrosis: case report and review of the literature. Am

over 3 days, which reflected a decrease in dose the third J Hematol 1998;57:233–7.

day after an initial increase in the patient’s INR. 8. Eby CS. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Hematol Oncol

Clin North Am 1993;7:1291–300.

CONCLUSION 9. DeFranzo AJ, Marasco P, Argenta LC. Warfarin-induced

necrosis of the skin. Ann Plast Surg 1995;34:203–8.

Skin necrosis is a rare but serious complication of

10. Jillella AP, Lutcher CL. Reinstituting warfarin in patients

oral anticoagulation therapy with warfarin—there are

who develop warfarin skin necrosis. Am J Hem 1996;52:

only approximately 200 reports. WISN occurred in our 117–9.

patient despite our following literature-recommended 11. Miura Y, Ardenghy M, Ramasastry S, et al. Coumadin

precautions for the administration of warfarin. Practi- necrosis of the skin: report of four patients. Ann Plas

tioners should consider this reaction when suspicious Surg 1996;37:332–7.

skin lesions appear, regardless of the manner in which 12. Sternberg, ML, Pettyjohn FS. Warfarin sodium-induced

warfarin treatment was initiated. HP skin necrosis. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:94–7.

Copyright 2002 by Turner White Communications Inc., Wayne, PA. All rights reserved.

42 Hospital Physician August 2002 www.turner-white.com

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Pediatric Musculoskeletal Summary For Osce ExamDokument53 SeitenPediatric Musculoskeletal Summary For Osce Examopscurly100% (2)

- Structural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969Dokument1 SeiteStructural and Dynamic Bases of Hand Surgery by Eduardo Zancolli 1969khox0% (1)

- 4 Fundamentals of Health Services ManagementDokument23 Seiten4 Fundamentals of Health Services ManagementMayom Mabuong100% (6)

- Nonoperative Management of Femoroacetabular ImpingementDokument8 SeitenNonoperative Management of Femoroacetabular ImpingementRodrigo SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linhart Continuing Dental Education ProgramDokument2 SeitenLinhart Continuing Dental Education ProgramnallatmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perioperative Hemodynamic MonitoringDokument9 SeitenPerioperative Hemodynamic MonitoringjayezmenonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Belo. Nur 192. Session 13 LecDokument3 SeitenBelo. Nur 192. Session 13 LecTam BeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theorists (W/ Their Theory/model) : Faye Glenn Abdellah Dorothy Johnson Imogene KingDokument3 SeitenNursing Theorists (W/ Their Theory/model) : Faye Glenn Abdellah Dorothy Johnson Imogene KingRodel P. Elep IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting The Extent of Compliance of Adolescent Pregnant Mothers On Prenatal Care ServicesDokument29 SeitenFactors Affecting The Extent of Compliance of Adolescent Pregnant Mothers On Prenatal Care ServicesNicole LabradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- सञ्चयकर्ता स्वास्थ्योपचार योजना सञ्चालन कार्यविधि, २०७७-50e1Dokument13 Seitenसञ्चयकर्ता स्वास्थ्योपचार योजना सञ्चालन कार्यविधि, २०७७-50e1crystalconsultancy22Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Dent4060Dokument10 Seiten2019 Dent4060Jason JNoch keine Bewertungen

- S: "Masakit Ang Ulo at Tiyan Niya" As Verbalized byDokument2 SeitenS: "Masakit Ang Ulo at Tiyan Niya" As Verbalized bydenise-iceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delayed Vs Immediate Umbilical Cord ClampingDokument37 SeitenDelayed Vs Immediate Umbilical Cord ClampingAndi DeviriyantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antenatal Care: Muhammad Wasil Khan and Ramsha MazharDokument55 SeitenAntenatal Care: Muhammad Wasil Khan and Ramsha MazharmarviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature ReviewDokument3 SeitenLiterature Reviewapi-609233193Noch keine Bewertungen

- Immune Response To Infectious DiseaseDokument2 SeitenImmune Response To Infectious Diseasekiedd_04100% (1)

- Learning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs)Dokument4 SeitenLearning Area Grade Level Quarter Date I. Lesson Title Ii. Most Essential Learning Competencies (Melcs)Ashly RoderosNoch keine Bewertungen

- N-Ophth Disorders in HIVDokument6 SeitenN-Ophth Disorders in HIVdwongNoch keine Bewertungen

- LINKSERVE Training MaterialsDokument15 SeitenLINKSERVE Training MaterialslisingynnamaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- VTR 214 PDFDokument2 SeitenVTR 214 PDFKimberly AndrzejewskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3in1 Shoulder BlockDokument2 Seiten3in1 Shoulder BlockTejasvi ChandranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impared NursesDokument11 SeitenImpared Nursesapi-240352043Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan Genito UrinaryDokument26 SeitenLesson Plan Genito UrinaryEllen AngelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health and Family Welfare (C) Department: PreambleDokument14 SeitenHealth and Family Welfare (C) Department: PreambleAjish BenjaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- MestastaseDokument10 SeitenMestastaseCahyono YudiantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heroine Source: by Waqas, Email 21waqas@stu - Edu.cnDokument14 SeitenHeroine Source: by Waqas, Email 21waqas@stu - Edu.cnwaqasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Priyanka Sen Final Practice School Internship ReportDokument35 SeitenPriyanka Sen Final Practice School Internship ReportThakur Aditya PratapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutrition Month 2011: Isulong Ang Breastfeeding - Tama, Sapat at Eksklusibo! (Tsek) ProgramDokument22 SeitenNutrition Month 2011: Isulong Ang Breastfeeding - Tama, Sapat at Eksklusibo! (Tsek) Programセル ZhelNoch keine Bewertungen

- MEdication ErrorsDokument6 SeitenMEdication ErrorsBeaCeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sitecore - Media Library - Files.3d Imaging - Shared.7701 3dbrochure UsDokument28 SeitenSitecore - Media Library - Files.3d Imaging - Shared.7701 3dbrochure UsandiNoch keine Bewertungen