Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

RRL Hypertension Compliance

Hochgeladen von

AngelaTrinidadOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

RRL Hypertension Compliance

Hochgeladen von

AngelaTrinidadCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Factors Associated with Treatment Compliance in Hypertension in Southwest Nigeria

Hypertension is an important condition among adults, affecting nearly one billion people worldwide. Treatment with appropriate medication is a key factor in the control of hypertension and reduction in associated risk of complications. However, compliance with treatment is often sub-optimal, especially in developing countries. The present study investigated the factors associated with self-reported compliance among hypertensive subjects in a poor urban community in southwest Nigeria. This community-based cross-sectional study employed a survey of a convenience sample of 440 community residents with hypertension and eight focus-group discussions (FGDs) with a subset of the participants. Of the 440 hypertensiverespondents, 65.2% were women, about half had no formal education, and half were traders. Over 60% of the respondents sought care for their condition from the hospital while only 5% visited a chemist or a patent medicine vendor (PMV). Only 51% of the subjects reported high compliance. Factors associated with high self-reported compliance included: regular clinic attendance, not using non-Western prescription medication, and having social support from family members or friends who were concerned about the respondent's hypertension or who were helpful in reminding the respondent about taking medication. Beliefs about cause of hypertension were not associated with compliance. The findings of the FGDs showed that the respondents believed hypertension is curable with the use of both orthodox and traditional medicines and that a patient who feels well could stop using antihypertensive medication. It is concluded that treatment compliance with antihypertensive medication remains sub-optimal in this Nigerian community. The factors associated with high self-reported compliance were identified. More research is needed to evaluate how such findings can be used for the control of hypertension at the community level. INTRODUCTION Hypertension is an overwhelming global challenge, which ranks third as a means of reduction in disability-adjusted life-years (1). It affects approximately one billion people worldwide (4.5% of the current global burden of disease)340 million of these in economically-developed and 340 million in economically-developing countries. Annually, it causes 7.1 million (or one-third of) global preventable premature deaths (2,3). Due to the fact that hypertension is one of the most important modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (4), treatment that commences once it is recognized reduces the cardiovascular risk of the individual. Therefore, access to treatment with antihypertensive medication and compliance with treatment are key factors in the control of hypertension. Hypertension, the leading cause of mortality and the third largest cause of disability, is poorly controlled worldwide. It is estimated that almost one-half of

patients drop out entirely from treatment within one year (5). The failure to control hypertension takes an unacceptable toll on patients and their families. In addition to the personal cost, to the individual patient, uncontrolled hypertension creates huge, avoidable economic burdens when viewed in terms of the general population.

The total number of estimated deaths resulting from all types of cardiovascular diseases and hypertensive heart disease recorded for Nigeria in 2004 by the World Health Organization (WHO) was 201,500 and 10,700 respectively (6) and placed Nigeria in the 16th position globally. Although these numbers are low compared to 922,700 and 229,000 deaths reported for the USA and the United Kingdom respectively, it is clear that there is a growing health problem that requires an intervention. Uncontrolled blood pressure has been demonstrated to be a major risk factor contributing to more than 500,000 cases of stroke and one million myocardial infarction cases reported each year in the United States alone (7). An estimated 14.55 million people, worldwide, aged 30-80 years, were reported to have died as a result of hypertensionrelated conditions in 2005, of which 7.03% were reported for sub-Saharan Africa (8).

Traditionally, the term compliance has been employed to mean the extent to which the patient, when taking a drug, complies with the clinician's advice and follows the regimen (9). Compliance with treatment is defined and characterized when medical or health advice coincides with the individual's behaviour with regard to the use of medication, recommended changes in lifestyle, and attendance to medical appointments (10). Poor compliance with treatment is the most important cause of uncontrolled blood pressure (11). Results of studies in the United States revealed that long-term compliance with treatment is always a problem in any chronic disease condition, and hypertension is no exception. More than 50% of patients in the United States, who were prescribed antihypertensive medications actually discontinued therapy within 12 months (12). A common reasongiven for stopping medication relates to adverse effects, although the patient's knowledge about the disease, attitudes regarding treatment of an often asymptomatic condition, and personal health beliefs, together with cost of medications and availability of healthcare, are major contributors (12).

Multiple factors contribute to poor compliance with long-term antihypertensive therapy. Many patients have negative attitudes towards taking medication, especially if they feel well (13). According to Jadelson et al., the major reasons for non-complianceare multi-factorial and range from lack of adequate guidance to socioeconomic status (14). Although the socioeconomic status has not consistently been found to be an independent predictor of compliance low

socioeconomic status may put patients in developing countries in the position of having to choose between competing priorities (15). Such priorities include demands to direct the limited resource available to meet the needs of other family members, such as children or parents, for whom they care. Some factors reported to have a significant effect on compliance are: poor socioeconomic status (poverty), low level of education, unemployment, lack of effective social support networks, unstable living conditions, long distance from treatment centre, high cost of transport, cultural and lay beliefs about illness and treatment, and forgetfulness (16).

The present study describes treatment-compliance patterns among hypertensive subjects in a Nigerian community and investigates the factors associated with good compliance, including demographic factors, beliefs about hypertension, and the availability of social support.

The study was conducted in the Idikan community, Ibadan, a city in the southwestern Nigeria, as part of a larger community-based study of the sociological aspects of hypertension. Idikan is located in the indigenous part of the city of Ibadan. Idikan is a densely-populated urban community within Ibadan city, with a population of 7,883 (17). Health facilities in the community include an outreach clinic run by the Department of Community Health of the University of Ibadan, a small dental clinic run by the Dental Centre of the University College Hospital (UCH), and private clinics. There are also registered patent medicine stores (pharmacies) and traditional healing homes in the area, all of which are accessible to members of the community.

The study consisted of two components: a quantitative study using a community-based survey of hypertensive subjects and a qualitative study using focus-group discussions (FGDs) on a subset of the participants. The subjects for the quantitative study were adult (aged above 25 years) residents of Idikan who are known to have hypertension. Previous studies in the community had conducted household screening for hypertension, which facilitated the identification of hypertensive subjects in the community. The subjects for this study were selected from a list of known hypertensive subjects residing in the community that was prepared for one such previous hypertension study (18) and was updated for the present study during visits to the home. Four hundred and forty hypertensive subjects were enrolled using a consecutive sampling method. The inclusion criteria were: (a) adults aged over 25 years, (b) having diagnosed hypertension by blood-pressure measurements, and (c) awareness of the hypertension status. The only exclusion criteria were refusal to participate and recent (less than three years) diagnosis of hypertension since the study required respondents to have experience

living with hypertension to be able to answer the questions. After obtaining informed consent, the subjects were administered a semi-structured questionnaire that had items on several issues, including healthcare-seeking for their hypertension, their beliefs about hypertension, compliance with treatment, and availability of social support (from family and friends).

The goal of the FGDs was to capture in-depth information that is complementary to the quantitative study (survey). This instrument guide had questions on knowledge, beliefs, perceptions, care-seeking behaviour, other experiences, and compliance with treatment for hypertension. Specific probes were included on the reasons (the why and how) for the respondent's beliefs, attitude, and actions regarding hypertension they have. Eight FGDs were carried out. A purposive sampling technique was used for selecting participants for group discussion, and discussants were homogeneous in characteristics within each group. There were four groups of males and four groups of females. Each group comprised 6-8 discussants. The inclusion criteria were individuals who were aged 45-60 years. They would have also been diagnosed of high blood pressure for 3-7 years. This allowed for having experiences living with hypertension while minimizing the forgetfulness of care-seeking over time. The key variable reflected in the composition of the focus groups was gender (male vs female). Gender is important because it reflects a major determinant of life experiences of people in the community and to ensure that the discussion and interaction among the participants in the FGDs is free and open. This provided relatively-homogenous focus groups that facilitated free and open discussion on which theamount of information that was elicited depends.

Analysis of data Management and analysis of the survey questionnaire data were done using the SPSS software (version 14) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Frequencies of the responses to the questions were computed and presented as percentages. The association between categorical variables was tested using the chi-square test. Compliance was defined using the question on how frequently people missed taking their medication. Compliance as a variable was defined and used in two ways. First, compliance was scaled as: high compliance (where the respondent never misses or rarely misses to take his/her medication doses); medium compliance (where the respondent sometimes misses taking medication); and low compliance (where the respondent regularly or fairly regularly misses to take his/her medication. T hese variables were used for identifying the factors associated with compliance in general. Second, since the desired goal of treatment for hypertension is that the patient complies with taking medication for controlling his/her high blood pressure, high compliance (where the respondent never

misses or rarely misses to take his/her medication doses) was used for identifying the variables associated with this goal of therapy.

Qualitative data were transcribed as soon as possible after each FGD session. The first author analyzed the qualitative data, reading through all notes and transcripts of the FGDs and identifying emerging themes relating to treatment compliance. Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS) was also done using the ATLAS.ti software.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the study protocol was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Of the 440 survey respondents, 65.2% were women. About half (51.1%) of the respondents had no formal education. In terms of occupation, 50% were traders, and about 26% were retired or not working while 11% were artisans. The respondents were aged 25-90 years. Their mean age was 60 [standard deviation (SD) 12] years. Dividing the age distribution of the respondents into 10-year bands, the peak age-categories were 46-55 years and 56-65 years comprising 29.3% and 29.1% of the respondents respectively. There was no significant relationship between the gender of the respondents and their age distribution. The large majority (71%) ofthe respondents were married (Table 1). A large proportion (63.4%) of the respondents sought care for their condition from a hospital (the University College Hospital, the community health centre, or a private hospital) while 5% visited a chemist or a patent medicine vendor. About 9.5% of the respondents who visited the hospital also used traditional medicine while 7.3% visited the chemist and used traditional medicine. None visited a traditional healer exclusively.

Factors associated with good compliance

Educational status and religion were two factors that often influenced knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and practices relating to health and other domains of life. The findings showed that high self-reported compliance was not associated with the religion professed by the respondent. Almost equal percentages of Muslims and Christians (57.8% vs 59.2%) showed high

self-reported compliance (2=0.797, p=0.671). Concerning education, there was no clear -cut trend with high self-reported compliance (2=6.683, p=0.245), although those with primary education showed a higher frequency of high self-reported compliance when compared with respondents with other categories of educational levels. Beliefs about the perceived cause of hypertension were not significantly associated with treatment compliance.

There was no association between believing that anxiety or stress is a cause of hypertension and high self-reported compliance. On the other hand, a higher percentage of those whose response to the question on the cause of hypertension was Do not know reported high compliance compared to those who professed to know the cause of hypertension (68.8% vs 56.2%) (Table 2). Keeping regular clinic appointments and use/non-use of non-Western medication were significantly (p<0.0001) associated with high self-reported compliance. Table 3 shows that the respondents who attended clinic appointments every time showed the highest percentage (67.5%) of high self-reported compliance compared to those who attended clinic appointments most times (42.1%) or less frequently. In other words, regularly keeping clinic appointments was positively associated with high self-reported compliance. In addition, the use of non-Western medication was also significantly related to high self-reported compliance: a significantly lower percentage of those who used non-Western medication showed higher selfreported compliance than those who did not (45.3% vs 63.8%, p<0.001).

The relationship between beliefs about hypertension may be important to know how well they comply with treatment. These beliefs include the notions that hypertension is preventable, is curable, is a serious condition, and can lead to complications. For these analyses, their relationships with compliance in general and with high self-reported compliance (as defined above) were explored. Of the other beliefs about hypertension studied, only the belief that hypertension medication can be stopped after a while was significantly (p=0.001) associated with compliance in general (Table 4). DISCUSSION Compliance with treatment is a very important issue in the successful control of hypertension andprevention of complications. In prescribing medication, compliance usually means the extent to which the patient takes the medication as prescribed (19). A number of factors influence compliance. The common belief that patients are solely responsible for taking their treatment is misleading and often reflects a misunderstanding of how other factors affect people's behaviour and capacity to adhere to their treatment.

Belief in the necessity of antihypertensive medication was high among the respondents, and the majority believed that it was necessary to take antihypertensive medication even if one does not feel sick. About 19% believed that one should only take medication when there are symptoms and had strong concerns about the potential adverse effects of taking medication every day or did not see the need for taking medication when one is not feeling ill. This finding also provides a preliminary insight into the mechanism by which beliefs relating to medication might influence compliance. Some of these findings were similar to those reported in previous studies (20,21). Familoni et al., in a 2004 study in Nigeria, reported that only about one-third of patients knew that hypertension should ideally be treated for life, and 58.3% believed that antihypertensive drugs should be used only where there are symptoms while the remaining 6.3% believed that the treatment should be for a period of time and not for life (22). Although it has been suggested that it is sometimes possible to withdraw drug therapy and continue lifestyle-modification after several years (23), the consensus is that almost all who are hypertensive before treatment will become hypertensive again if treatment is stopped. This practice has sometimes resulted in disastrous consequences.

There are many concepts that refer to compliance, for example compliance, adherence, commitment, and concordance. According to Kontz, the most important t hing is how the content of the concept is defined (24). A major factor accounting for the inadequate treatment of hypertension is poor compliance. The findings of this study revealed that almost half of the respondents reported high compliance with treatment with drug, and 86% claimed high compliance with keeping their appointments with doctors. Reasons for compliance with treatment include fear of the complications of hypertension and the desire to control blood pressure. Benson, in 2002, reported that patients comply with medication regimen for various reasons, including perceived benefits of medication, fear of complications associated with hypertension, and feeling better on medication (21). The latter reason is contrary to the generally-held belief among physicians that hypertension is a largely asymptomatic disease (25).

Interestingly, about one-half of the study respondents were non-compliant to their medication. The results of the FGDs suggest that the decision to stop using antihypertensive medication is influenced by the beliefs the respondents hold concerning these medications. The identification of the factors determining non-compliance and a better knowledge about them could allow the implementation of measures that could enable their correction and providing the adequate

control of blood-pressure levels. In this study, reasons for non-compliance with medication are multifactorial and range from low level of knowledge regarding hypertension as a disease and lack of adequate guidance to socioeconomic aspects. The identification of side-effects of treatment used represents another cause of non-compliance with treatment. This finding lays credence to the submission of Hyman and Pavlik that a primary reason given for stopping medication relates to adverse effects, although the patient's knowledge about the disease, attitudes towards treatment of an often asymptomatic condition, and personal health beliefs, together with cost of medications and the availability of healthcare, are major contributors (12). One central theme that runs through the data in this study is the issue of socioeconomic status of the respondents. Financial hardship is a significant barrier to complying with treatment and is a contributory factor to non-compliance. If people are hungry, nothing matters, except food. People either take medication very late when they have had something to eat or forget about it while trying to deal with other problems of poverty. This finding corroborates the observed association among poor compliance, ignorance, and lack of funds for the purchase of drugs reported by Isezuo and Opara (26).

While stress and anxiety were the two most common perceived causes of hypertension among the respondents, the findings showed that those who held these beliefs did not show better compliance than others. However, those who did not know the cause of hypertension showed better compliance with medication than others. This implies that not having preconceived ideas about the cause of hypertension made it more likely that the respondents would comply with treatment. This observation was also common to other beliefs about hypertension (being curable, preventable, serious, leading to complications, and so on) where those who responded Do not know showed a tendency to better compliance. Other studies that have investigated the relationship between beliefs and compliance reported that patient's belief and lack of knowledge, along with other factors, influenced their response to treatment (27,28).

Social support networks are important in the long-term management of chronic conditions, such as hypertension, which requires a radical and life-long change in the lifestyle of the affected person. In the present study, those who had support from friends or family members (concerned about their illness, giving reminders about medication) had better compliance with treatment than those who did not, although this difference was the greatest for those who had the support of friends. This is an important finding and is consistent with what has been reported for multiple chronic diseases in several parts of the world (29). Interestingly, the evidence from the present study shows that support from friends is a stronger factor influencing high self-reported compliance than support from family members. This may be a

reflection of the fact that most people in the community (and in cities in general) see, talk, and interact more with their friends than with their family members who do not live nearby. Another explanation may be that those with hypertension are more likely to discuss their health problems with their friends than with their family members, thereby inadvertently limiting the support they could receive from the latter.

Limitation

A potential limitation of this study is that compliance was measured using self-report and, therefore, suffers from the problems of recall. Inclusion of methods, such as pill-counts or more sophisticated electronic methods, may have helped more accurately assess compliance. However, this was not feasible within the context of a community-based study. Nonetheless, the study provides useful data in this important area of compliance to therapy for a noncommunicable disease.

Conclusions It is concluded that the control of hypertension is still sub-optimal in this community, with only one-half of the affected persons reporting high compliance with treatment. The factors associated with high self-reported compliance included: regular clinic attendance, not using non-Western prescription medication, and having social support from family members or friends who were concerned about the respondent's hypertension or who were helpful in reminding the respondent about taking medication. Most respondents believed that hypertension is curable with the use of both orthodox and traditional medicines and that a patient who feels well could stop using antihypertensive medication. On the other hand, specific beliefs about the cause of hypertension were not associated with compliance.

It is recommended that similar research be conducted in developing countries on factors affecting compliance in hypertension and similar diseases that require life-long medication for control. Furthermore, studies are needed on how such findings can be used for guiding local hypertension-control efforts.

A grounded theory of patient medication noncompliance in men diagnosed with hypertension

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 2011 Dissertation Author: Richard C Edwards

Although research regarding patient noncompliance has increased, no consensus has emerged regarding the superiority of any theory, model, or tool to understand the causes of noncompliant behavior. The purpose of this qualitative, grounded theory study was to use inductive analysis to discover a theory of noncompliance that explains medication noncompliance. Research questions examined respondents perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes towards their medical care; their relationship with their health care provider; and how these factors affected their behavior (taking medications). Twenty five men, ages 30-50 years, who were clinically diagnosed with hypertension and were not regularly taking their medication, participated in the interviews. Semistructured interviews were completed with the men, and open, axial, and selective coding were used to identify emergent themes and patterns in the data. Results showed that noncompliance is not a unitary phenomenon but rather reflects a variety of cognitive and emotional influences. Financial instability, provider trust, and locus of control for medication compliance were concepts that emerged to explain noncompliance. It is recommended that the emergent model be tested in larger samples as well as among those with other health conditions. Implications for social change include improved provider education on factors related to noncompliance, improved communication between patients and health care providers, heightened trust, and recognition that improving compliance is a mutual responsibility of patients and providers. Implications for social change also include improved compliance which can lead to better physical health as well as decreased health care costs for individuals suffering from health conditions. CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW Introduction The purpose of this study was to determine why patients do not comply with a health care providers orders or instructions. In this chapter, I review the literature on patient noncompliance. Reasons for noncompliance and the relevance of grounded theory for a study of this type are reviewed. In grounded theory research, a literature review can serve as part of data collection and as a source of emergent theory. This

review covers patient surveys, adverse drug events, demographics, socioeconomics, providerpatient relationships, communication, and trust. Appendix A includes a summary of peerreviewed research. An initial literature search was conducted using Ovid and PubMed databases. PubMed is accessible from any personal computer with Internet access, but Ovid is only accessible through Area Health Education Center (AHEC) digital libraries located at AHEC facilities. The Ovid search was performed by library staff at the Southern Regional AHEC, and the search results were forwarded to me. Search results that were not available from PubMed or Ovid were furnished through the U.S. Army Medical Command Library at Womack Army Medical Center. The initial search used the following terms: medication, federal patient standards, primary care, adherence, quality patient standards, compliance, noncompliance, physician,and relationship. That search yielded 184 sources. After the initial search results, I conducted a second search using terms more specific to the study: noncompliance, medication, prescriptions, prescription medications, patient noncompliance,and surveys. That search yielded 52 sources. An additional PubMed 14 search using the term medication noncompliance surveys yielded 347 sources, many of which were either disease-specific or confined to a specific component such as cost- benefit ratio or automated drug dispensing monitoring. Patient Surveys and Noncompliance Loghman-Adham (2003) wrote, The study of human behavior in relation to taking medications or following medical advice has not kept pace with scientific breakthroughs. As medicines become more effective, access to health care and patient noncompliance will become the leading causes of treatment failure. (p. 155) The most significant detrimental effect of noncompliance is economic. According to Renal Data Systems, noncompliance has a direct impact on hospitalization, Medicare and Medicaid, and insurance expenditures in excess of $1300 per patient per day (as cited in Loghman-Adham, 2003, p. 155), amounting to $100 billion a year (Wertheimer & Santella, 2003b, p. 207). Chapman (2004) noted that many researchers have attempted to determine risk factors for noncompliance, which range from persistent failure to take the prescribed medication at one extreme or single episodes of noncompliance at the other extreme (p. 782). According to Wertheimer and Santella (2003a), a multiplicity of studies focusing on adherence [compliance] has resulted in conflicting data and contradictory results over the last 25 years (p. 257). No specific noncompliance surveys are discussed in the literature; instead, patient responses regarding noncompliance are included in studies with broader noncompliance themes. Some researchers have speculated that patients who are surveyed may not want to admit they are noncompliant in their medication regimens (Egede, 2003; Taylor, 15

Galbraith, & Mills, 2002). When surveyed patients admit they are noncompliant, they might fear that a health care provider will view their behavior as demonstrating a lack of confidence in the way they comply with the medical recommendations (Waeber, Burnier, & Brunner, 2000, p. S25). Haynes et al. (2007) found several valid reasons for noncompliance, including poor instructions, poor provider-patient relationship, and patients disagreement with the need for treatment (p. 2). One tool for determining noncompliance is the medication possession ratio (MPR), a measurement of the first prescription to the last prescription. The MPR provides some degree of certainty that a patient is taking medications as prescribed (Cooke & Fatodu, 2006). Providers have found, however, that some patients stop and then restart taking a medication, sometimes call the toothbrush effect (Denzii, 2001, p. 44), which suggests there may well be a vacuum of noncompliance that has not been accounted for (p. 44). Most postdischarge patient surveys attempt to assess provider quality and do not include medication noncompliance as a measure of that quality. Provider quality surveys list services rendered, including how patients are greeted when they approach the front desk and how they are treated by staff and nurses (White, 1999). Patient satisfaction surveys show your staff and the community that youre interested in quality (White, para. 2), which becomes a mark eting tool. According to Fromer, If we physicians dont get on board and try to make the data as good as possible and get our scores as high as possible, were going to be hurt in the marketplace. Well be noncompetitive. Thats the biggest reason of all to be doing this. (as cited in White, 1999, para. 3) 16 One popular postdischarge patient survey is the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health care Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). It has a core set of questions that can be combined with customized, hospital-specific items (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2007, para. 2). The HCAHPS does not include any medication noncompliance items. Adverse Drug Events and Noncompliance Cohen (2001) found that patients typically quit their prescribed medication regimens after 1 year. Zyczynski and Coyne (2000) found that after the first 6 months of use, persistence decreased to 84% and after 4.5 years of observation, only 47% of patients persisted with their initially prescribed agent (p. 513). Cohen reviewed data from a Saskatchewan study that revealed a dropout rate of 22% the first year and 54% after 4.5 years. Those researchers determined that patients were receiving adequate medication counseling but that providers relied too heavily on information provided by the Physicians Desk Reference. Patients fear of adverse drug events (ADE) is a factor in noncompliance, but surveys do not specifically address that issue. Dsing (2001) suggested that side effects may directly or indirectly underlie variable compliance and nonpersistence (p. 488) and should be addressed; but, Shenolikar et al. (2004) found that 84% of the patients surveyed did not think their prescribed medication regimen

would have negative side effects. Haynes et al. (2007) cited six studies showing that telling patients about adverse effects of treatment did not affect their adherence (p. 1). 17 Time The length of time a patient spends with a provider and remains with the same provider over multiple visits is directly related to patient satisfaction and health (see Table 5). Table 5 Patient Satisfaction and Provider Relationship Patient- Provider Relationship Remained with Provider Saw Same Provider Trust Level Communication Score Provider Knowledge of Patient Quality of Health > 3 years Most a,c Most a Increased d Increased d Increased d Increased d < 3 years 66% b 95% b ,c Decreased d Decreased d Decreased d Decreased d a Donahue, Ashkin, and Pathman (2005). b Helme and Harrington (2004). c Fan, Burman, McDonell, and Fihn (2005). d Parchman and Burge (2003). Wilson et al. (2007) suggested that developing familiarity with the patient in a long-term relationship could be associated with less vigilance by the physician or less counseling in areas in which the patient may have initially shown resistance (p. 7). Based on the satisfaction and trust achieved in long-term patient-provider relationships, however, it is not unreasonable to expect that fostering long-term relationships between patients and their physicians may help promote the outcome of greater patient satisfaction (Wilson et al., 2007, p. 7). Loghman Adham (2003) found that a strong relationship between the patient and health provider is associated with improved compliance (p. 161). Duration of a patient-provider over time is not the only temporal variable to be considered. The length of consultation time is also important. McGrath (1999) found that 18 some providers voiced concerns that they had insufficient time to counsel patients about their medication regimens and any associated ADEs. Feldman, Murtaugh, Pezzin, McDonald, and Peng (2005) noted that various studies have attempted to trace the impact of changes in practitioner behavior to actual improvements in patients self- management of chronic conditions or to patient outcomes (pp. 865-866); but, most patient surveys do not link a providers behavior to a patients noncompliance. Demographic and Socioeconomic Data Regarding the effect of demographic variables on noncompliance, Schillinger et al. (2000) found no statistically significant differences with regard to gender, race/ethnicity, language capabilities, prior outpatient and inpatient utilization, proportion with attending-level primary care physicians, distance from the hospital (by zip code), or prevalence of chronic medical

conditions (p. 332). On the other hand, Wilson et al. (2007) found that noncompliant patients were more likely to be nonwhite, without health insurance, less educated, *to+ report income of less than $25,000 and . . . [to have] fair to poor health st atus (p. 5). It should be noted that these patients were responding to Medicare prescription drug benefit law changes in 2006. Piette, Heisler, Krein, and Kerr (2005) concluded that although socioeconomic status could be a causal factor in noncompliance, other findings suggest that factors other than cost may either only buffer or accentuate the impact of financial pressures on patients adherence behavior (p. 1749). They only included diabetic patients who used Veterans Health Administration hospitals. 19 Provider-Patient Relationships, Communication, and Trust Schneider et al. (2004) used crosssectional analysis to determine if better provider-patient relationships and verbal communication would reduce noncompliance in patient medication regimens. Participants were from the metropolitan Boston area. They found no relationship between adherence and specific measures of the provider-patient relationship (p. 1096). On the other hand, Chapman (2004) found that patients would like their physicians to teach them [how to take their medications], tell them about new/alternate medications and procedures as they become available, and offer new ways to make their regimen easier (p. 401). Murphy et al. (2001), in a study of insured patients, found that the quality of interpersonal treatment affected patients willingness to comply with medical advice or treatment'' (p. 124). Specifically, the quality of the provider-patient relationship has been associated with outcomes that include patients compliance with medical advice (Murphy et al., 2001, p. 126). Murphy et al. concluded that effective provider-patient communication can do things like build trust and reduce the emotional stress of a patient (p. 126). This in turn can help the provider diagnose and has an effect on both management decisions and ultimately results in a positive health outcome (p. 126). Trust is an important part of the patient-provider relationship. Kerse et al. (2004) found that trust, or concordance, was related to continuity and patient satisfaction (p. 456) and that primary care consultations with higher levels of patient-reported provider-patient concordance were associated with one-third greater medication compliance (p. 455). Krupat et al. (2002) found that trust in the provider-patient relationship reduced noncompliance to prescribed medical regimen recommendations. 20 Wilson et al. (2007) studied provider-patient communication with patients on Medicare and Medicaid. They found a correlation between noncompliance and dialogue between patients and providers. Among patients surveyed with three or more chronic conditions, 24% reported they had not discussed their medication regimens with their provider for over 12 months since their last visit. Also, 38% admitted noncompliance when changing their original prescription

medication to a generic medication and not initially discussing this with their provider. Cline, Bjrck-Linn, Israelsson, Willenheimer, and Erhardt (1999) found that the information given to patients appears uncomplicated and is reinforced by medication charts, thus allowing patients the possibility to refer to it if they were unsure of the verbal instructions (p. 148). When patients were surveyed regarding their prescriptions, only 55% of the patients could correctly name what medication had been prescribed, 50% were unable to state the prescribed doses, and 64% could not account for when the medication was to be taken (Willenheimer & Erhardt, 1999, p. 147). Although providers verbally described appropriate medication regimen instructions, apparently they did not determine patients ability to understand and adhere to the regimen. McGrath (1999) concluded that the nature of provider-patient communication is unclear in particular as there have been no studies that have investigated physicians perspectives and how they might shed light on the problem of noncompliance (p. 732). McGrath added that compliance would improve if patient-provider communication improved (p.732). Larson & Yao (2005) argued that a healing patient-provider relationship and communication were essential to quality healthcare and had a direct impact on compliance

Why hypertensive patients do not comply with the treatment

Results from a qualitative study Juan J Gascna, Montserrat Snchez-Ortuob, Bartolom Llorc, David Skidmored, Pedro J Saturnoa,c and for the Treatment Compliance in Hypertension Study Group

Background. Medical non-compliance has been identified as a major public health problem in the treatment of hypertension. There is a large research record focusing on the understanding of this phenomenon. However, to date, the majority of studies in this field have been focused from the medical care perspective, but few studies have focused on the patients' point of view.

Objective. Our aim was to identify factors related to non-compliance with the treatment of patients with hypertension.

Methods. We use a qualitative study in which data were gathered from seven focus group discussions conducted in MarchMay 2001. Patients were identified as non-compliant, using the MoriskyGreen test, at two primary health care centres of the Spanish National Health Service.

Results. A complex web of factors was identified that influenced non-compliance. Patients had fears and negative images of antihypertensive drugs. The data also revealed a lack of basic background knowledge about hypertension. The clinical encounter was viewed as unsatisfactory because of its length, few explanations given by the physician and low physician patient interaction.

Conclusions. Most of the factors related to poor compliance have implications for patient management. Knowing patients' priorities regarding the most important aspects of care that have high potential for low compliance may be helpful in improvement of the quality of hypertensive patient care.

Key words Hypertension patient compliance physicianpatient relations Gascn JJ, Snchez-Ortuo M, Llor B, Skidmore D and Saturno PJ for the Treatment Compliance in Hypertension Study Group. Why hypertensive patients do not comply with the treatment. Results from a qualitative study. Family Practice 2004; 21: 125130. Hypertension is the single most common and most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease.1 Despite improvements in the detection and treatment of hypertension since the 1970s, recent survey results illustrate that the condition continues to contribute, significantly, to mortality and morbidity in adults and that it is often poorly controlled in clinical practice.2 Similarly, other studies suggest that the treatment's efficacy, in patients under care, is attenuated mainly by patient non-compliance with medication and lifestyle advice.3 In fact, it has been estimated that only 60% of patients take medication as prescribed.4

Given the broad scope of the problem, ever-increasing attention has been devoted to identifying factors which contribute to non-compliance.5 To date, the majority of studies in this field have been carried out in Anglo-Saxon contexts and have been focused on establishing, from the medical care perspective, the factors related to non-compliance; however, fewer studies have focused on the patients' points of view. The last suggest that patients' noncompliance could be associated with reservations about drugs and lack of necessary knowledge on which to build an understanding of the condition and treatment.68

We, therefore, decided to explore patients' opinions and expectations concerning hypertension and its treatment in another socio-cultural settings. To address this issue, we designed a qualitative study, based on the focus groups technique, intended to provide an in-depth perspective about poor compliance in hypertension.9

Participants The target population comprised non-compliant hypertensive patients who were diagnosed with and receiving treatment for hypertension. Inclusion criteria were: anyone between the ages of 18 and 80 years, being treated with antihypertensives for >3 months, being noncompliant and having sufficiently good physical and mental health to participate. Detailed information about the type of antihypertensive or duration of treatment could not be collected.

Procedure In order to determine whether or not the patient was compliant, a telephone survey was first conducted among 267 hypertensive patients, identified from clinic and computer records from two primary health care centres in Murcia (Spain). The MoriskyGreen test10 was used in this survey. Those patients who scored 1 point in the test were considered to be non -compliant and hence potential participants (n = 146).

Letters were sent to patients, identified as non-compliant, asking them if they would be prepared to help with some research on patients' experiences of hypertension. Approximately 1 week later, they were contacted by telephone in order to ascertain their commitment to attend and to remind them of the session. An average of 20 patients at a time was contacted by telephone to participate in each focus group until no new themes or ideas were emerging (n = 141). A total of 44 patients, 24 men and 20 women, participated in the seven focus groups sessions where conventional consent and confidentiality procedures were followed. Group size varied from three to 11, and sessions lasted 4080 min. We felt that our participants might be diffident in discussing issues related to their health in the presence of the opposite sex and therefore decided to have separate male and female groups. The venues selected for the focus groups were neutral, being located neither in university nor hospital premises.

The focus group interview In order to elicit information on the patient's perspective of their condition, their treatment and the relationship with the provider, pre-determined, open-ended questions were arranged by way of a guided interview. Topics for the guided interview were determined by a review of the relevant literature and in consultation with colleagues (psychologists and GPs). The interview form covered four domains: the diagnosing of hypertension; the patient's understanding of the

condition; perception of the relationship between patient and health care provider; and any difficulties in following the treatment (Box 1).

Box 1 Focus group interviewing guide How did you find out that you had high blood pressure?

How do you feel about having high blood pressure?

What have you been told about high blood pressure and its treatment?

Have you found it easy to follow the instructions?

Is there anything you would like to say about the care you have received whilst attending the surgery?

What do you and the doctor usually talk about in the surgery?

When you have taken medication, how has it been for you?

What kind of problems do you encounter when taking the medication?

All focus groups were facilitated by two of the authors (MSO and PPF) who represent different backgrounds (psychology and medicine).

Each session began with introductions and a brief explanation of the reasons for the study and of its confidentiality. The same set of questions was posed for each group, although not strictly

in the same order. Participants were encouraged to talk freely and, if they brought up relevant points spontaneously, the order of the questions was varied to maintain the flow of the session.

Data analysis With patients' permission, sessions were videotaped and later transcribed verbatim. The analysis was inductive and followed established conventions for ensuring that the process was grounded in the data rather than reflecting a pre-determined analytic framework.11 The analysis followed several stages. (i) In order to obtain an overall impression, the transcripts were read repeatedly by seven researchers (JJG, MSO, BL, DS, PJS, PPF and JJA), who represent three disciplines (medicine, psychology and sociology). (ii) The seven researchers identified, independently, emergent themes. This process was iterative, with new data used to assess the integrity of the developing analysis. (iii) The researchers met to compare analysis and an ongoing dialogue between the researchers contributed to the shaping of the definite categories. (iv) To validate the categories, they were compared with established concepts in published research in this field from the initial literature review. (v) JJG and MSO examined each interview line by line to identify relevant text units to be categorized according to the established underlying categories. To ensure compatibility of text categorizing, the two researchers analysed three transcripts jointly and the others separately. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved by discussion. The analysis was finalized when all relevant text could be categorized.

The researchers checked the plausibility of the data interpretation and ensured that the qualitative data analysis was systematic and verifiable, as recommended by experts.9 As we aimed to find aspects related to non-compliance, our analysis focused on negative rather than positive outcomes.

Factors identified as influencing treatment compliance fell into three categories: beliefs and attitudes about antihypertensive drugs; beliefs and attitudes about hypertension; and clinical encounters.

Beliefs and attitudes towards antihypertensive drugs

Fears were expressed about the long-term use of antihypertensive medication and the possibility of being stuck with it for the rest of one's life. Negative feelings were elicited in many cases, as antihypertensives were perceived as being damaging and not good for the body. The adverse effects of drugs were issues of concern to most subjects. In addition, we identified remarks indicating that the information on medicines provided in leaflets was frightening and difficult to understand. I was afraid of the medication, because I was told that once I started to take it I would have to take it all my life. (Participant 2; focus group 2) I think that has to be damaging to some part of my body. (Participant 6; focus group 7) I don't like them (medicines), they have lots of side effects, they can make you sick I think that I might get worse instead of better. (Participant 1; focus group 2) I read the whole leaflet but I don't understand anything, and even the doctor doesn't explain it. (Participant 1; focus group 4) I don't even want to read the leaflet, if I did I would never take any medication. (Participant 4; focus group 2)

When analysing the accounts participants gave of the medication that they were currently taking, we found that some patients thought that it was perfectly safe not to take it from time to time and some admitted that they did not always take medication as prescribed. Sometimes this was simply because they forgot it, especially if the drug had to be taken at regular intervals throughout the day. We also found that many patients regarded drug taking as conditional to the symptoms they were experiencing and, basically, because they felt well, some claimed that they had tried to gain personal experiences of the medicines by experimenting to see how they felt without them. Associated with this idea was the desire to find out about alternatives such as reducing the prescribed dose or stopping treatment for a while, once the blood pressure seemed to be controlled. In some cases, the length and routine nature of the treatment caused boredom and, consequently, the desire to drop out. Furthermore, it was also suggested that there was more confidence in herbal or natural remedies taken due to common knowledge than in medicines to alleviate hypertension. My problem is that I forget to take my medication during the day when I don't have it right beside me. (Participant 3; focus group 7) I've stopped taking the tablets when I've felt like it, sometimes for a fortnight or three weeks just to see. (Participant 6; focus group 6)

If my blood pressure feels more controlled, I've reduced the dose myself. (Participant 3; focus group 7) I'm really tired I've been taking medication for thirty-one years now and I'm fed up so sometimes I say I'm just going to stop taking it for a while. (Participant 3; focus group 7) I take lemons that's what helps me the most but the doctors don't tell you that: (Participant 5; focus group 4) I only take the medication because it (blood pressure) doesn't go above 14 or 15; if they went any higher I'd just boil up some nettles and take that. (Participant 9; focus group 6)

Beliefs and attitudes about hypertension The fact of having high blood pressure did not seem worrisome for patients and was often associated with certain well-recognized familiar symptoms, as if the absence of them meant that blood pressure was controlled. The doctor told me your blood pressure's a bit high, 1617 but I didn't think that was important . (Participant 6; focus group 3) I have to feel sick, or have a sore neck and then I'll have my blood pressure taken. (Participant 3; focus group 1)

The knowledge which the majority of patients had regarding hypertension had been acquired from sources other than the physician, such as magazines, TV programmes on health or talking to other people. As a result, a strong need for further knowledge, provided by the physician, is identified by many subjects. Anything I know about blood pressure I've read in books, the doctor tells me absolutely nothing I want him to tell me where high blood pressure comes from. (Participant 4; focus group 1)

Clinical encounters The majority of patients complained about the length of the consultation. They claimed that little time was spent with regard to informing; indeed most of the consultation time was used just to get the prescription. In keeping with this, there was the perception of the physician as

always being busy, and this was mentioned in several cases. In many cases, it was stated that physicians did not give any spontaneous information and asked few questions. In addition, it was emphasized that the physician seldom made eye contact during the consultation and spent the time just taking notes. Other statements were made to the effect that it was difficult to understand the physician's language or writing. You only get to see the doctor for five minutes. (Participan t 3; focus group 1) There's not really any conversation, you're there explaining what's wrong with you and he doesn't even look at you, he's just taking notes He sends you away with a few words here is your prescription and that's it. (Participant 7; focus group 6) The doctors could pay a bit more attention at least or explain things, because sometimes they explain it and you just don't understand they should explain it in a different way so that you can understand. (Participant 1; focus group 2) In the chemist they write on the box how I have to take the medication because I can't understand what the doctor wrote. (Participant 4; focus group 5)

Some reported that the encounter with the physician created nervousness and that they did not ask what they wanted to know. It is felt that the physician did not encourage patient interaction and did not help to create the context that elicits the patients' underlying concerns about hypertension and its treatment. Whenever I go to the doctor I would want to ask if I can go running or if it's OK to ride a bicycle or not, but when I go into the surgery I don't feel comfortable and I forget everything I wanted to ask. (Participant 1; focus group 4) He doesn't even give you the chance to tell him anything or to ask questions. (Participant 2; focus group 2)

In the consultation, the most common lifestyle changes recommended were reductions of salt intake and some exercise, but there were no rational explanations provided by the physician on why these changes were beneficial. This information was considered by the patients to be too general and not tailored to the individual. They give you advice: stop smoking and take some physical exercise, but they don't tell you, say, how to go walking or if you can ride a bicycle or not. (Participant 1; focus group 4)

They've told me hundreds of times that I have to lose weight and I just don't know how because they never explain how to do it. (Participant 7; focus group 6)

This study reveals a complex web of factors that can influence compliance behaviour within a group of patients diagnosed with hypertension (Figure 1). Although all the findings are not new with respect to previous literature, these serve to confirm what has been found previously, in the Spanish context. At first glance, the results indicated negative feelings towards medicines, low awareness about the condition and dissatisfaction with clinical encounters as barriers with regard to following treatment advice. Some of these factors were similar to those found in other studies on compliance in hypertension.7,8,12,,13 In the main, these factors can be summarized in two categories: patient and physician context related. Most of them do have clear implications for patient management, as the predominant view that emerges is that there is plenty of room for improvement in the patientphysician communication. First, it is, arguably, surprising to discover that patients with a chronic condition, such as hypertension, lack basic background knowledge about it, such as its potential risks and why it is important to follow the prescribed treatment even in the absence of symptoms. So it does not seem odd that they also have lay knowledge and beliefs on medication that can, consequently, reduce compliance. These must be addressed by the physician and, if this is the case, adequate information should be provided to reduce the fear and anxiety derived from the use of medicines, and hence this will improve compliance. Even so, this study shows that, in the ordinary clinical situation, patients often fail to understand what they are told and, what is more, without this primary basis the patient cannot build up a rationale for the therapy.14 This aspect of the doctorpatient relationship has been visited previously, where it was argued that doctors offer simple instructions on several occasions and yet the patient, due largely to anxiety, does not receive such information.15 This puts the physician in a unique position of responsibility and opportunity to act not only as diagnostician but also as a qualified patient educator. In this respect, participants in the focus groups put the highest emphasis on physician's empathetic qualities, in being interested, listening and devoting time to patients.

An exploration of these issues may help the physician discuss with the patient the appropriateness of the proposed treatment and to find alternatives.

This implies that a new perspective on health care, one which goes beyond the biomedical side of medicine, is needed and that physicians must become more active in their interactions with

the patients and be able to examine the patient's understanding of the world. To achieve this goal, the use of interpersonal skills training among health professionals has been suggested.16

However, it can be argued that the time limits of family physician consultations and resource constraints are an obstacle to addressing the individual needs. We consider that a practical solution could be the integration of group visits into the family practice routine. The meeting of several patients with the family physician at the same time allows a more efficient use of the family physician's consultation time and a better interaction with patients, as the group approach may facilitate communication, sharing concerns with the doctor and, therefore, compliance.17

The study had some limitations. Focus group studies have some potential disadvantages, which the researcher should be aware of. They involve relatively small numbers of people, which means that there is a probability of the findings not being representative of the general population in terms of the opinions voiced. However, this qualitative study was designed to highlight this phenomenon, and not to measure variables. The application of qualitative methods has provided an in-depth view of a complex area of clinical care that can promote more comprehensive and sensitive measurement of factors related to non-compliance.

All of this led to the conclusion that knowing patients' priorities regarding the most important aspects of care that have high potential for low compliance may be helpful in improvement of the quality in the care of the hypertensive patient.

Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod MJ. Source Department of Medicine and Therapeutics, Medical School, University of Aberdeen, Despite many years of study, questions remain about why patients do or do not take medicines and what can be done to change their behaviour. Hypertension is poorly controlled in the UK and poor compliance is one possible reason for this. Recent questionnaires based on the selfregulatory model have been successfully used to assess illness perceptions and beliefs about medicines. This study was designed to describe hypertensive patients' beliefs about their illness and medication using the self-regulatory model and investigate whether these beliefs influence compliance with antihypertensive medication. We recruited 514 patients from our secondary care population. These patients were asked to complete a questionnaire that included the Beliefs about Medicines and Illness Perception Questionnaires. A case note review was also undertaken. Analysis shows that patients who believe in the necessity of medication are more likely to be compliant (odds ratio (OR)) 3.06 (95% CI 1.74-5.38), P<0.001). Other important predictive factors in this population are age (OR 4.82 (2.85-8.15), P<0.001), emotional response to illness (OR 0.65 (0.47-0.90), P=0.01) and belief in personal ability to control illness (OR 0.59 (0.40-0.89), P=0.01). Beliefs about illness and about medicines are interconnected; aspects that are not directly related to compliance influence it indirectly. The self-regulatory model is useful in assessing patients health beliefs. Beliefs about specific medications and about hypertension are predictive of compliance. Information about health beliefs is important in achieving concordance and may be a target for intervention to improve compliance.

Hypertension - Medical and Nursing Management

Hypertension is also called as High blood pressure. Hyper meaning High and Tension meaning Pressure. Pressure is the force generated when the heart contracts and pump blood through the blood vessels that conduct the blood to various parts of the blood. Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a persistent blood pressure above 90 mm Hg between the heart beats (diastolic) or over 140 mm Hg at the beats (systolic).

Hypertension does not in itself give dramatic symptoms, but it is dangerous because it causes a highly increased risk for heart infarction, stroke and renal failure.

There are two major types of hypertension: Essential or primary hypertension and secondary hypertension. Primary hypertension is the most common condition, found in 95 per cent of the cases. It has no definite cause. There are several factors that may act in combination, causing the blood pressure to increase. Secondary hypertension is found in five to ten per cent the cases. Here, the increase in blood pressure is caused by a specific defect in one of the organs in the body. Treating the affected organ can control or cure the hypertension.

The direct mechanisms causing hypertension is one or more of these factors: An increased tension in the blood vessel walls.

An increased blood volume caused by elevated levels of salt and lipids in the blood holding back water. Hardened and inelastic blood vessels caused by arteriosclerosis.

The primary causes behind these mechanisms are not fully understood, but these factors contribute to causing hypertension: A high consume of salt A high fat consume. Stress at work and in the daily life. Smoking. Over-weight Lack of exercise. Kidney failure.

Hypertension Symptoms: Some of the common symptoms of hypertension are: Giddiness, Dizziness and a Feeling of Instability. Palpitations. Insomnia (inability to sleep well). Digestive problems and Constipation.

Hypertension is only determined through a blood pressure measurement equipment and reads the systolic and diastolic of the blood. There is actually no identified sign of hypertension; rather, it varies from one person to another. Some people report to have experienced headaches, fatigue, dizziness, blurring of vision and facial flushing.

Symptoms only surface when signs of end-organ damage are determined or are possible; otherwise, the condition is still considered accelerated hypertension. Malignant hypertension, on the other hand, is caused by increased intracranial pressure. These could be diagnosed through retinal examination.

Medical Management for Hypertension

When lifestyle measures and supplements are not enough to cure the condition, medical treatment must be applied.

Diuretics, or medicines to increase the urine production, are used to decrease the water content in the blood vessels, and thereby reduce the pressure in the vessels. When the water content is lowered, the heart does not need to pump so hard any more, and this will also reduce the pressure.

Beta-adrenergic blockers are another group of medicines to treat hypertension. This group of medicines block the signals that hormones and neurotransmitters give to the vessel walls, and the vessel walls then relax. They also slow down the heart rate to give a lower pressure exerted by the heart upon the blood.

Nursing Management for Hypertension Diet Diet for Hypertension The diet is recommended for patients with hypertension: Moderate salt restriction of 10 g / day to 5 g / day Diets low in cholesterol and low in saturated fatty acids Weight loss Decrease your intake of ethanol

Stopping smoking Physical Exercise Physical Exercise for Hypertension Physical exercise or regular exercise and directed that recommended for patients with hypertension is a sport that has four principles: Various forms of exercise that is isotonic and dynamic such as running, jogging, cycling, swimming, etc. The intensity of exercise is good between 60-80% of aerobic capacity or 72-87% of the maximum pulse-called training zone. The duration of exercise ranged from 20-25 minutes on the exercise zone Frequency should exercise 3 times per week and at least a good 5 x per week Education Psychological Provision of psychological education for hypertensive patients include: Biofeedback techniques - Biofeedback is a technique that is used to indicate the subject of the signs of the state of the body that is consciously by the subject is not considered normal. Application of biofeedback is mainly used to treat somatic disorders such as headaches and migraines, as well as for psychological disorders such as anxiety and tension. Relaxation techniques - Relaxation is a procedure or technique that aims to reduce tension or anxiety, a way to train people to be able to learn to make the muscles in the body to relax Health Education (Extension) The purpose of health education is to increase patient knowledge about hypertension and its management so that patients can maintain life and prevent further complications.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Weekly Requirement OB WardDokument12 SeitenWeekly Requirement OB WardXerxes DejitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAS 7 - Abapo, Aquea B.Dokument3 SeitenSAS 7 - Abapo, Aquea B.Aquea Bernardo AbapoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Nursing Care Plan: Partially AchievedDokument3 SeitenFamily Nursing Care Plan: Partially AchievedENKELI VALDECANTOSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching PlanDokument4 SeitenTeaching PlanDickson,Emilia JadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Quality of Hospital Outpatient Departments: Patients' PerspectiveDokument2 SeitenService Quality of Hospital Outpatient Departments: Patients' Perspectivelouie john abilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family NRSG and The Nursg Process Hand Out Week 11 J.dimayugaDokument25 SeitenFamily NRSG and The Nursg Process Hand Out Week 11 J.dimayugaYanis Emmanuelle LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- ROLES RESPONSIBILITIES OF A MC NURSE IN CHALENGEING SITUATIONS Merged Compressed Merged MergedDokument53 SeitenROLES RESPONSIBILITIES OF A MC NURSE IN CHALENGEING SITUATIONS Merged Compressed Merged MergedYuuki Chitose (tai-kun)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case-Study-Final-1 BOSET NA CASE PRESENTATIONDokument57 SeitenCase-Study-Final-1 BOSET NA CASE PRESENTATIONGiselle EstoquiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociogram and DocumentationDokument6 SeitenSociogram and DocumentationRaidis PangilinanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group #4: Unit Task #1 (Nursing Research I)Dokument11 SeitenGroup #4: Unit Task #1 (Nursing Research I)AriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Framework For Prevention: Nancy MilioDokument9 SeitenFramework For Prevention: Nancy MilioBrenlei Alexis NazarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity # 2 NAME - DATEDokument4 SeitenActivity # 2 NAME - DATEJamie Haravata100% (1)

- Midterm Period Course Task 2 Nurse Researcher Role.Dokument7 SeitenMidterm Period Course Task 2 Nurse Researcher Role.Jhanina CapicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- SAS Session 4 Research 1Dokument6 SeitenSAS Session 4 Research 1Leaflor Ann ManghihilotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research1 Sessions 1 6.docx-1Dokument6 SeitenResearch1 Sessions 1 6.docx-1Sabrina MascardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Health Nursing Journal PDFDokument2 SeitenCommunity Health Nursing Journal PDFRuthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orientation On Community Health - Doh Programs & ServicesDokument11 SeitenOrientation On Community Health - Doh Programs & ServicesAudrey Beatrice ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Swot AnalysisDokument1 SeiteSwot AnalysisKelly Posadas-MesinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RRLDokument4 SeitenRRLAnnalyn MantillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- COMMUNITY-MANUSCRIPT SampleDokument84 SeitenCOMMUNITY-MANUSCRIPT SampleCA SavageNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCLFNP - Mr. Robert McClelland CaseDokument4 SeitenNCLFNP - Mr. Robert McClelland CaseAiresh Lamao50% (2)

- Nursing Informatics Timeline (CENIZA BSN 3E)Dokument1 SeiteNursing Informatics Timeline (CENIZA BSN 3E)FATIMA IVAN S. CENIZANoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Research ReportDokument15 SeitenNursing Research Reportapi-546467833Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hizon 2 NCP 1 Npi I Am SamDokument5 SeitenHizon 2 NCP 1 Npi I Am SamDan HizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Identification and PrioritizationDokument2 SeitenProblem Identification and PrioritizationSheena Mae FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birthing Beliefs in The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenBirthing Beliefs in The PhilippinesJeeyan DelgadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Er Journal HgeDokument3 SeitenEr Journal HgeKit LaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Presenttaion (GRP 1, 3BSN-13) Ra (2NCP)Dokument22 SeitenCase Presenttaion (GRP 1, 3BSN-13) Ra (2NCP)Lorelyn Santos Corpuz100% (1)

- Lecture - Chapter 2Dokument13 SeitenLecture - Chapter 2Lawrence Ryan DaugNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goals & Objectives: I. Patient CareDokument4 SeitenGoals & Objectives: I. Patient CareBhawna PandhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Week 2 NCM 107Dokument21 SeitenWeek 2 NCM 107raise concern100% (1)

- 109lec Week 5Dokument16 Seiten109lec Week 5claire yowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP. MOuth SoreDokument1 SeiteNCP. MOuth SoreChriszanie CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Diagnosis Sample PDFDokument2 SeitenCommunity Diagnosis Sample PDFLisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Pcap CDokument3 SeitenJournal Pcap CKit Lara50% (2)

- Nur 154 P1Dokument16 SeitenNur 154 P1Naomi VirtudazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- José Rizal University College of Nursing and Health SCIENCES S.Y. 2021-2022 / First SemesterDokument84 SeitenJosé Rizal University College of Nursing and Health SCIENCES S.Y. 2021-2022 / First Semesterlea mae andoloyNoch keine Bewertungen

- RHD & H - Mole - Case PresDokument90 SeitenRHD & H - Mole - Case PresGhra CiousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tpo Eo Poa LFDDokument4 SeitenTpo Eo Poa LFDEzra Miguel DarundayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2NF - Grand Case Presentation Written OutputDokument99 Seiten2NF - Grand Case Presentation Written OutputKyra Bianca R. FamacionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buddy WorksDokument3 SeitenBuddy WorksJamaica Leslie NovenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- n320 - Peds - WK 1 - ReflectionDokument2 Seitenn320 - Peds - WK 1 - Reflectionapi-245887979Noch keine Bewertungen

- Activity#1 - Development of CCRNDokument4 SeitenActivity#1 - Development of CCRNJennah JozelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuro Vital SignsDokument3 SeitenNeuro Vital SignsKrissa Lei Pahang Razo100% (1)

- Narrative ReportDokument2 SeitenNarrative ReportJanina Cate D TorrecampoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP Alzheimers DiseaseDokument2 SeitenNCP Alzheimers DiseaseShawn TejanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Honesty in MedicineDokument3 SeitenImportance of Honesty in MedicineSuiweng WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Nursing Care PlanDokument1 SeiteFamily Nursing Care PlanBhaby Che AserdnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liceo de Cagayan University College of Nursing Review of Related Literature and StudiesDokument13 SeitenLiceo de Cagayan University College of Nursing Review of Related Literature and StudiesMiles AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Nursing Care PlanDokument14 SeitenFamily Nursing Care PlanTenth Ann ModanzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HEALTH-TEACHING (Safety)Dokument3 SeitenHEALTH-TEACHING (Safety)Asterlyn ConiendoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apply The HBM and HPM in The Following SituationDokument1 SeiteApply The HBM and HPM in The Following SituationMary Ruth CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tube Reflective EssayDokument2 SeitenChest Tube Reflective EssayAnjae GariandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Case Study ofDokument28 SeitenPulmonary Tuberculosis: A Case Study ofDyanne BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Factors Affecting Nurse Performance in Medical WardDokument6 SeitenFactors Affecting Nurse Performance in Medical Wardifa pannyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHN PTDokument2 SeitenCHN PTYzobel Phoebe ParoanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic ActDokument36 SeitenRepublic ActjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3B GRP 2 Community Health PlanDokument14 Seiten3B GRP 2 Community Health PlanIsabelle Hazel BenemileNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Epidemiology and Global HealthDokument9 SeitenJournal of Epidemiology and Global HealthparameswarannirushanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypertension Protocol JeannineDokument53 SeitenHypertension Protocol JeannineAleile DRNoch keine Bewertungen

- IRB Roles For ReferenceDokument33 SeitenIRB Roles For ReferenceAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application LetterDokument1 SeiteApplication LetterAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Teleconsultation For Filipino CliniciansDokument25 Seiten2 Teleconsultation For Filipino CliniciansTwinkle Salonga0% (1)

- BacterialkeratitisDokument58 SeitenBacterialkeratitisAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pterygium & DacryocystitisDokument45 SeitenPterygium & DacryocystitisAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coronavirus Pandemic Anxiety Scale (CPAS-11) : Development and Initial ValidationDokument9 SeitenCoronavirus Pandemic Anxiety Scale (CPAS-11) : Development and Initial ValidationMarvin M PulaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cream Modern Vision & Mission PosterDokument2 SeitenCream Modern Vision & Mission PosterAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trauma: Patient Name Age/Sex Chief Complaint History of Present IllnessDokument1 SeiteTrauma: Patient Name Age/Sex Chief Complaint History of Present IllnessAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trauma: Patient Name Age/Sex Chief Complaint History of Present IllnessDokument1 SeiteTrauma: Patient Name Age/Sex Chief Complaint History of Present IllnessAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grand Rounds: Andy Chien, MD, PHD University of Washington Division of DermatologyDokument75 SeitenGrand Rounds: Andy Chien, MD, PHD University of Washington Division of DermatologyVaibhav KaroliyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Urinary Tract Infections in ChildrenDokument12 Seiten2018 Urinary Tract Infections in ChildrenYudit Arenita100% (1)

- Chronic DiseasesDokument24 SeitenChronic DiseasesAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ditas Cristina D Decena MD MPH: Recomendation For Preventing Exposure To Toxic ChemicalsDokument29 SeitenDitas Cristina D Decena MD MPH: Recomendation For Preventing Exposure To Toxic ChemicalsAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Case 1Dokument4 SeitenSample Case 1AngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide For Small Intestine and AppendixDokument5 SeitenStudy Guide For Small Intestine and AppendixAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casestudy Gastric CarcinomaDokument53 SeitenCasestudy Gastric CarcinomaAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minimally Invasive Surgery (Mis) : Roberto O. Domingo, M.D.,FPCSDokument51 SeitenMinimally Invasive Surgery (Mis) : Roberto O. Domingo, M.D.,FPCSAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of A Self Rating Scale of Self Directed Learning PDFDokument18 SeitenDevelopment of A Self Rating Scale of Self Directed Learning PDFAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharma - M6L2 - Drug Therapy For OA and Gouty ArthritisDokument8 SeitenPharma - M6L2 - Drug Therapy For OA and Gouty ArthritisAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuroscience Ii: Summary: Nationality (Will Tell You Incidence, For Example, AsiansDokument29 SeitenNeuroscience Ii: Summary: Nationality (Will Tell You Incidence, For Example, AsiansAngelaTrinidad100% (2)

- NeurologicDokument7 SeitenNeurologicFarrah ErmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharma - M6L1 - Drug Therapy For Selected STI'sDokument27 SeitenPharma - M6L1 - Drug Therapy For Selected STI'sAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Beda College of Medicine Batch 2017 Neuro-Pedia ChecklistDokument9 SeitenSan Beda College of Medicine Batch 2017 Neuro-Pedia ChecklistAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pharma - M6L4 - Pediatric Fluid Computation in DehydrationDokument7 SeitenPharma - M6L4 - Pediatric Fluid Computation in DehydrationAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

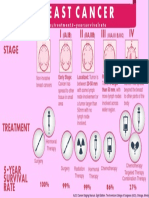

- Breast Cancer InfogrpahicDokument1 SeiteBreast Cancer InfogrpahicAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Varicella Post-ProphylaxisDokument2 SeitenVaricella Post-ProphylaxisAngelaTrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Declaration of Alma AtaDokument3 SeitenDeclaration of Alma AtaJustin James AndersenNoch keine Bewertungen