Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Air Material Wing Savings and Loan Association, Inc. vs. NLRC

Hochgeladen von

Fayda CariagaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Air Material Wing Savings and Loan Association, Inc. vs. NLRC

Hochgeladen von

Fayda CariagaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

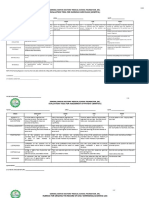

AIR MATERIAL WING SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATION, INC. VS. NLRC G.R. NO. 111870.

June 30, 1994 FACTS: Private respondent Luis S. Salas was appointed "notarial and legal counsel" for petitioner Air Material Wings Savings and Loan Association in 1980. The appointment was renewed for three years in an implementing order dated January 23, 1987. Subsequently, on January 9, 1990, the petitioner issued another order reminding Salas of the approaching termination of his legal services under their contract. This prompted Salas to lodge a complaint against AMWSLAI for separation pay, vacation and sick leave benefits, cost of living allowances, refund of SSS premiums, moral and exemplary damages, payment of notarial services rendered from February 1, 1980 to March 2, 1990, and attorney's fees. Instead of filing an answer, AMWSLAI moved to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction. It averred that there was no employer-employee relationship between it and Salas and that his monetary claims properly fell within the jurisdiction of the regular courts. Salas opposed the motion and presented documentary evidence to show that he was indeed an employee of AMWSLAI. Nevertheless, most of Salas' claims were dismissed by the labor arbiter in his decision dated November 21, 1991. It was there held that Salas was not illegally dismissed and so not entitled to collect separation benefits. His claims for vacation leave, sick leave, medical and dental allowances and refund of SSS premiums were rejected on the ground that he was a managerial employee. He was also denied moral and exemplary damages for lack of evidence of bad faith on the part of AMWSLAI. Neither was he allowed to collect his notarial fees from 1980 up to 1986 because the claim therefore had already prescribed. However, the petitioner was ordered to pay Salas his notarial fees from 1987 up to March 2, 1990, and attorney's fee equivalent to 10% of the judgment award. On appeal, the decision was affirmed in toto by the respondent Commission, prompting the petitioner to seek relief in the Supreme Court, hence, the case at bar. ISSUE: whether or not Salas can be considered an employee of the petitioner company RULING: The Supreme Court had held in a long line of decisions that the elements of an employeremployee relationship are: (1) selection and engagement of the employee; (2) payment of wages; (3) power of dismissal; and (4) employer's own power to control employee's conduct. The terms and conditions set out in the letter-contract entered into by the parties on January 23, 1987, clearly show that Salas was an employee of the petitioner. His selection as the company counsel was done by the board of directors in one of its regular meetings. The petitioner paid him a monthly compensation/retainer's fee for his services. Though his appointment was for a fixed term of three years, the petitioner reserved its power of dismissal for cause or as it might deem necessary for its interest and protection. No less importantly, AMWSLAI also exercised its power of control over Salas by defining his duties and functions as its legal counsel, to wit: (1) To act on all legal matters pertinent to his Office; (2) To seek remedies to effect collection of overdue accounts of members without prejudice to initiating court action to protect the interest of the association; and (3) To defend by all means all suit against the interest of the Association. In the earlier case of Hydro Resources Contractors Corp. vs. Pagalilauan (G.R. No. L-62909, April 18, 1989), the Court observed that: A lawyer, like any other professional, may very well be an employee of a private corporation or even of the government. It is not unusual for a big corporation to hire a staff of lawyers as its in-house counsel, pay them regular salaries, rank them in its table of organization, and otherwise treat them like its other officers and employees. At the same time, it may also contract with a

law firm to act as outside counsel on a retainer basis. The two classes of lawyers often work closely together but one group is made up of employees while the other is not. A similar arrangement may exist as to doctors, nurses, dentists, public relations practitioners and other professionals. The Supreme Court holds, therefore, that the public respondent committed no grave abuse of discretion in ruling that an employer-employee relationship existed between the petitioner and the private respondent. ACCORDINGLY, the appealed judgment of the NLRC is AFFIRMED, with the modification that the award of notarial fees and attorney's fees is disallowed.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Mutants & Masterminds 3e - Power Profile - Death PowersDokument6 SeitenMutants & Masterminds 3e - Power Profile - Death PowersMichael MorganNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50 - Nina Jewelry Manufacturing of Metal Arts Inc. vs. Montecillo, G.R. No.Dokument2 Seiten50 - Nina Jewelry Manufacturing of Metal Arts Inc. vs. Montecillo, G.R. No.Hello123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 3rd Edition e Bruce GoldsteinDokument24 SeitenTest Bank For Cognitive Psychology Connecting Mind Research and Everyday Experience 3rd Edition e Bruce GoldsteinMichaelThomasyqdi100% (49)

- Agrarian ReformDokument40 SeitenAgrarian ReformYannel Villaber100% (2)

- Labor DIGESTDokument9 SeitenLabor DIGESTAdmin DivisionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dee ChuanDokument4 SeitenDee ChuanBurn-Cindy AbadNoch keine Bewertungen

- GREAT PACIFIC LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION vs. HONORATO JUDICO and NLRCDokument3 SeitenGREAT PACIFIC LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION vs. HONORATO JUDICO and NLRCemman2g.2baccayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dy Keh Beng - DigestDokument2 SeitenDy Keh Beng - DigesthaaaaaaaaaayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moro Vs Del CastilloDokument5 SeitenMoro Vs Del CastilloEricson Sarmiento Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Makati Haberdashery Vs NLRCDokument2 SeitenMakati Haberdashery Vs NLRCIda Chua67% (3)

- AVELINO VSNLRCDokument1 SeiteAVELINO VSNLRCJanex Tolinero100% (1)

- Asian Transmission Corp V CADokument2 SeitenAsian Transmission Corp V CAApple MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- (KASAMMA-CCO) - CFW LOCAL 245 Vs CA Case DigestDokument2 Seiten(KASAMMA-CCO) - CFW LOCAL 245 Vs CA Case DigestAtheena Marie PalomariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB vs. PNB Emplyees AssociationDokument3 SeitenPNB vs. PNB Emplyees Associationtalla aldoverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Producers Bank Vs NLRCDokument1 SeiteProducers Bank Vs NLRCCj GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case No. 8 Kasapian NG Malayang Manggagawa Sa Coca Cola Et Al Vs CADokument2 SeitenCase No. 8 Kasapian NG Malayang Manggagawa Sa Coca Cola Et Al Vs CAaerosmith_julio662750% (2)

- Aurora Land Projects Corp. Vs - NLRCDokument3 SeitenAurora Land Projects Corp. Vs - NLRCShiela Padilla50% (2)

- Sorreda V Cambridge Electronics CorpDokument5 SeitenSorreda V Cambridge Electronics CorpClement del RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Digest - Makati Haberdashery and Sentinel CasesDokument3 SeitenLabor Digest - Makati Haberdashery and Sentinel CasesSui100% (1)

- 2 Opulencia Ice Plant and Storage Vs NLRCDokument2 Seiten2 Opulencia Ice Plant and Storage Vs NLRCBryne Boish100% (1)

- Vinoya v. National Labor Relations Commission, G.R. No. 126586Dokument3 SeitenVinoya v. National Labor Relations Commission, G.R. No. 126586Kathryn Nyth KirklandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paringit v. Global Gateway DigestDokument4 SeitenParingit v. Global Gateway DigestBong OrduñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zuellig Pharma Corp. v. Sibal (Digest)Dokument2 SeitenZuellig Pharma Corp. v. Sibal (Digest)Eumir SongcuyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI Employees Union vs. BPI G.R. No. 137863 March 31, 2005 FactsDokument3 SeitenBPI Employees Union vs. BPI G.R. No. 137863 March 31, 2005 FactsRey Almon Tolentino AlibuyogNoch keine Bewertungen

- METRO TRANSIT ORGANIZATION v. NLRCDokument2 SeitenMETRO TRANSIT ORGANIZATION v. NLRCGabriel Literal100% (1)

- 1 College of Immaculate Conception Vs NLRCDokument3 Seiten1 College of Immaculate Conception Vs NLRCMadz Rj MangorobongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Takata Vs BLRDokument2 SeitenTakata Vs BLRChris Ronnel Cabrito CatubaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oliver vs. Macon Hardware Co It Was Held That in Determining Whether A Particular Laborer orDokument1 SeiteOliver vs. Macon Hardware Co It Was Held That in Determining Whether A Particular Laborer orana ortizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law (Prelims) : Prelinary Title Chapter 1 (General Provisions) Art 1. Name of DecreeDokument20 SeitenLabor Law (Prelims) : Prelinary Title Chapter 1 (General Provisions) Art 1. Name of DecreeAllyson LatosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farle P. Almodiel vs. National Labor Relations Commission (First Division), Raytheon Phils., Inc. FactsDokument2 SeitenFarle P. Almodiel vs. National Labor Relations Commission (First Division), Raytheon Phils., Inc. FactsMeki100% (1)

- MAraguinot V Viva Films DigestDokument2 SeitenMAraguinot V Viva Films DigestcattaczNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.E. Automotive Employees V Noriel G.R. No. L-44350Dokument5 SeitenU.E. Automotive Employees V Noriel G.R. No. L-44350Apay Grajo100% (1)

- Labor 9 To 12 CasesDokument3 SeitenLabor 9 To 12 CasesbiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranaw Hotels and Resorts Corp Vs CA, SottoDokument1 SeiteMaranaw Hotels and Resorts Corp Vs CA, Sottois_still_artNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maraguinot vs. NLRC Case DigestDokument1 SeiteMaraguinot vs. NLRC Case Digestunbeatable38100% (1)

- 264 Wellington Investment vs. TrajanoDokument1 Seite264 Wellington Investment vs. TrajanoKim CajucomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor CompiledDokument95 SeitenLabor CompiledKarina GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lynvil Fishing Enterprises IncDokument2 SeitenLynvil Fishing Enterprises IncChristineCoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portillo v. Rudolph-Lietz Inc. G.R. 196539, Oct 10, 2012Dokument1 SeitePortillo v. Rudolph-Lietz Inc. G.R. 196539, Oct 10, 2012homestudy buddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vigilla V PH College of Criminology - Labor (JACINTO)Dokument3 SeitenVigilla V PH College of Criminology - Labor (JACINTO)Peter Joshua OrtegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gelmart Industries Phil., Inc., Vs NLRCDokument2 SeitenGelmart Industries Phil., Inc., Vs NLRCNolaida AguirreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davao Fruits Corporation Vs Associated Labor Unions in Behalf of Employees of DAVAO FRUITS CORPORATION and NLRCDokument2 SeitenDavao Fruits Corporation Vs Associated Labor Unions in Behalf of Employees of DAVAO FRUITS CORPORATION and NLRCMaden Agustin100% (1)

- 6 Nitto Enterprises vs. NLRC and Roberto CapiliDokument1 Seite6 Nitto Enterprises vs. NLRC and Roberto CapiliJerome Dela Cruz DayloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tupas v. NLRCDokument14 SeitenTupas v. NLRCWinter WoodsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoemart Inc vs. NLRCDokument6 SeitenShoemart Inc vs. NLRCMonica FerilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palacol Vs Ferrer-CallejaDokument9 SeitenPalacol Vs Ferrer-CallejamjpjoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hocheng Phil. Corp Vs FarralesDokument2 SeitenHocheng Phil. Corp Vs Farraleslovekimsohyun8967% (3)

- Labor Law Case DigestDokument95 SeitenLabor Law Case DigestInter_vivos100% (1)

- JPL Marketing Promotions Vs Ca Case DigestDokument1 SeiteJPL Marketing Promotions Vs Ca Case DigestRouella May AltarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beta Electric Corp To ALU-TUCPDokument7 SeitenBeta Electric Corp To ALU-TUCPNN DDLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law Case SyllabusDokument97 SeitenLabor Law Case Syllabusileen maeNoch keine Bewertungen

- BibosoDokument1 SeiteBibosoKimberly RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Case Digests 7Dokument7 SeitenLabor Case Digests 7Ezra Joy Angagan CanosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 73 Manila Banking Corp Vs NLRCDokument14 Seiten73 Manila Banking Corp Vs NLRCRay Carlo Ybiosa AntonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Federation of Labor Vs NLRCDokument1 SeiteNational Federation of Labor Vs NLRCagvitorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rolando Roxas Surveying Company Vs NLRCDokument2 SeitenRolando Roxas Surveying Company Vs NLRCGraziel Edcel Paulo0% (1)

- Anti-Age Discrimination in Employment ActDokument1 SeiteAnti-Age Discrimination in Employment ActKarissa TolentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- NLRC Creation and Composition (Article 220, PD 442)Dokument10 SeitenNLRC Creation and Composition (Article 220, PD 442)Raiza CuliNoch keine Bewertungen

- B Recruitment and Placement - UnlockedDokument20 SeitenB Recruitment and Placement - UnlockedAthena SalasNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19Dokument2 Seiten19GoodyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRIMINAL LAW 6th Week PDFDokument42 SeitenCRIMINAL LAW 6th Week PDFRhea PolintanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Material Wings V NLRCDokument2 SeitenAir Material Wings V NLRCEds GalinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AmwslaiDokument4 SeitenAmwslaiJackie CalayagNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.M. No. P-08-2458Dokument1 SeiteA.M. No. P-08-2458Fayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases To DigestDokument20 SeitenCases To DigestFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor CasesDokument211 SeitenLabor CasesFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest InsuranceDokument28 SeitenDigest InsuranceFayda Cariaga100% (1)

- PALE Nos 2-19Dokument48 SeitenPALE Nos 2-19Fayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LetterDokument1 SeiteLetterFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Davao Fruits Corporation vs. Associated Labor Unions (Alu)Dokument2 SeitenDavao Fruits Corporation vs. Associated Labor Unions (Alu)Fayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primitivo Siasat Vs IacDokument3 SeitenPrimitivo Siasat Vs IacFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martinez v. Ong Pong CoDokument4 SeitenMartinez v. Ong Pong CoFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AFFIDAVIT NewDokument3 SeitenAFFIDAVIT NewFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anastacio Viaña vs. Alejo Al-LagadanDokument2 SeitenAnastacio Viaña vs. Alejo Al-LagadanFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of CasesaDokument9 SeitenList of CasesaFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ferdinand Marcos Raul Manglapus: Constitutional Law Ii Topic: Liberty of AbodeDokument1 SeiteFerdinand Marcos Raul Manglapus: Constitutional Law Ii Topic: Liberty of AbodeFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Food Authority (NFA) v. IACDokument2 SeitenNational Food Authority (NFA) v. IACFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alfonso Del Castillo vs. Shannon RichmondDokument1 SeiteAlfonso Del Castillo vs. Shannon RichmondFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abante V LamadridDokument1 SeiteAbante V LamadridFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primitivo Siasat Vs IacDokument3 SeitenPrimitivo Siasat Vs IacFayda CariagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acitve and Passive VoiceDokument3 SeitenAcitve and Passive VoiceRave LegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where Is The Love?-The Black Eyed Peas: NBA National KKK Ku Klux KlanDokument3 SeitenWhere Is The Love?-The Black Eyed Peas: NBA National KKK Ku Klux KlanLayane ÉricaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isolated Foundation PDFDokument6 SeitenIsolated Foundation PDFsoroware100% (1)

- Music 10: 1 Quarterly Assessment (Mapeh 10 Written Work)Dokument4 SeitenMusic 10: 1 Quarterly Assessment (Mapeh 10 Written Work)Kate Mary50% (2)

- Sona Koyo Steering Systems Limited (SKSSL) Vendor ManagementDokument21 SeitenSona Koyo Steering Systems Limited (SKSSL) Vendor ManagementSiddharth UpadhyayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Boarding Announcement Skill Focus: ListeningDokument5 SeitenPre-Boarding Announcement Skill Focus: ListeningJony SPdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsDokument2 SeitenCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen PlanusDokument1 SeiteA Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen Planus600WPMPONoch keine Bewertungen

- HSE Induction Training 1687407986Dokument59 SeitenHSE Induction Training 1687407986vishnuvarthanNoch keine Bewertungen

- COSL Brochure 2023Dokument18 SeitenCOSL Brochure 2023DaniloNoch keine Bewertungen

- SATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...Dokument55 SeitenSATYAGRAHA 1906 TO PASSIVE RESISTANCE 1946-7 This Is An Overview of Events. It Attempts ...arquivoslivrosNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEDIA OPD RubricsDokument11 SeitenPEDIA OPD RubricsKylle AlimosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalDokument38 Seiten06 Ankit Jain - Current Scenario of Venture CapitalSanjay KashyapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Vegetation in Western EuropeDokument12 SeitenTypes of Vegetation in Western EuropeChemutai EzekielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Based LearningDokument23 SeitenProblem Based Learningapi-645777752Noch keine Bewertungen

- God Made Your BodyDokument8 SeitenGod Made Your BodyBethany House Publishers56% (9)

- dm00226326 Using The Hardware Realtime Clock RTC and The Tamper Management Unit Tamp With stm32 MicrocontrollersDokument82 Seitendm00226326 Using The Hardware Realtime Clock RTC and The Tamper Management Unit Tamp With stm32 MicrocontrollersMoutaz KhaterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of The Tata Consultancy ServiceDokument20 SeitenAnalysis of The Tata Consultancy ServiceamalremeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrenal Cortical TumorsDokument8 SeitenAdrenal Cortical TumorsSabrina whtNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDokument8 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 61 Point MeditationDokument16 Seiten61 Point MeditationVarshaSutrave100% (1)

- Effect of Innovative Leadership On Teacher's Job Satisfaction Mediated of A Supportive EnvironmentDokument10 SeitenEffect of Innovative Leadership On Teacher's Job Satisfaction Mediated of A Supportive EnvironmentAPJAET JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendix I - Plant TissuesDokument24 SeitenAppendix I - Plant TissuesAmeera ChaitramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Signal&Systems - Lab Manual - 2021-1Dokument121 SeitenSignal&Systems - Lab Manual - 2021-1telecom_numl8233Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2-Emotional Abuse, Bullying and Forgiveness Among AdolescentsDokument17 Seiten2-Emotional Abuse, Bullying and Forgiveness Among AdolescentsClinical and Counselling Psychology ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bio Lab Report GerminationDokument10 SeitenBio Lab Report GerminationOli Damaskova100% (4)

- Indiabix PDFDokument273 SeitenIndiabix PDFMehedi Hasan ShuvoNoch keine Bewertungen