Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Zecchi

Hochgeladen von

mercurymouthCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Zecchi

Hochgeladen von

mercurymouthCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Meghan McCormack

Zecchi

I dont think theyll let me back in the U.S. with a jar of insect blood. The mysterious liquid may cause them think Im carrying a disease or that Im a vampire fanatic or possibly terrorist. So I pack my brown oak gall pigment and my blood ink up in a plastic bag and sadly store them away in the armoire. When my friend and I stopped to visit Stefano, he didnt stop chattering about music. He only paused to slip out of his office at the Cortona Library and disappear into the adjacent room for a second. He returned and, without missing a beat, dropped a book, as thick as a full edition of The Oxford English Dictionary in my lap. Thunk. Then, with no explanation, he tossed some white gloves beside me on the leather couch. He continued to chatter to my friend as I slipped on the gloves, bewildered. When I opened the book, I went into a sort of trance. In red and black medieval lettering, I saw La Divina Commedia di Dante Alighieri scripted on the title page. Nearby, the year 1331was scrolled in small red numbers. It was one of the first manually copied editions of Dantes Divine Comedy! I turned the pages with my gloved fingers. Each page was so thick. Though there were hardly any illustrations, the prose was printed in small brown-black medieval script with elaborate enlarged capitals in red at the beginning of each section. Dante died in September of 1321 and worked on The Divine Comedy from 1308 until the time of his death. His words must have been so fresh at the time the manuscript

was made. The language inscribed on the pages was to become the foundation of standard Italian and there it was in one of its very first incarnations, in my lap, in my hands. I suddenly felt that my body was bolted to the couch, frozen by the knowledge any sudden movement could wreck an 800-year-old work of art. I finally interrupted Stefano and made him explain a thing or two. Oh yeah, there are all kinds of old manuscripts in this place. Use the gloves so the oils in your fingers dont damage the pages. The pages are made of sheep or goat skin or sometimes bladders. His words were clipped, efficient. Then he turned the discussion back to a far more interesting topic in his mind: PJ Harvey. Stefano did not know that I obsess over lettering. I grew up with generic pen and ink sets, something my family was happy to provide for me because it meant I would stop drawing and writing on the walls. With those sets, I discovered what was probably the only thing that ever truly came naturally to me. I felt a kinship to the manuscript in front of me and started letting my imagination go a little bezerk. Maybe I was an illuminator in a past life--an Irish monk even. Maybe I copied and illustrated great prose or great tales, thereby preserving them from becoming defunct. I probably worked in one of those Irish monasteries Thomas Cahill talked about in How the Irish Saved Civilization. I may have rescued great knowledge from the barbaric medieval thugs by copying Aristotle, Plato, and other great thinkers. Or maybe I was one of those women who held a job as a scribe or illuminator at the end of the commercial manuscript era (before the onset of the printing press) who secretly produced my own stories. Or maybe I should stop entertaining this ridiculous and dorky fantasy

and just accept that looking at old manuscripts makes me feel warm and fuzzy and thats just that. I even made money cranking out wedding envelopes for my mothers friends daughters when I was just a teenager. The chore was a bit tedious, but relaxing at the same time. After those wedding projects, I had set my lettering and graphic calligraphy aside, dismissing it as an obsolete art. Who cared? Who made real money doing it? What was the point anyway? Working in Florence a few years after my encounter with Stefano, I started frequenting a store on Via dello Studio that my artist friends talked about. That Dante manuscript was still tickling my mind. Ultimately, I had the Zecchi brothers and their kids to thank for my new red ink and for giving me back my art form. In the 1950s, the Zecchi brothers decided to make the original recipes of Medieval and Renaissance pigments available to the local art community. Some hadnt been available for decades and others for centuries. One brother managed the store while the other traveled the world to capture the organic materials that are alive and well in Giotto, Boticelli and Michelangelo and tons of early paintings, but had become defunct over the centuries, replaced by manufactured chemical paints or acrylics. Lapuz lazuli, for example, an expensive stone was once used primarily for the blues of the Madonna robes in altarpieces. Greens made of crushed malachite, yellows of saffron flower or ochre, warmed the gowns of the angels around her. The Zecchis brought in the royal blue stone from the Middle East, crushed and placed in a jar alongside an array of other colored powders, all from natural plant or mineral sources. They relied heavily on Cenninis craftsmans Handbook from the early 1400s, which lists

important ingredients and practices for artists. Cennini also dishes out advice that artists would surely scoff at today like dont drink too much alcohol if you want to be a good artist. Near the powders stood a shelf stocked with inks. I saw the bottle of Carmine Cochineal and paused and lifted the crimson bottle from the shelf. The thought of using the red ink thrilled me because it contained a traceable, history I had read about. Combined with the art form, using the ink seemed like it would call on some old way of being, like a dead vernacular, that I might be able to revive or at least experience in some small way. I brought it to the counter. My new ink was made of blood of cochineal, an insect found on cacti. It has been used in manuscripts since antiquity it became a common red in illuminated books, court documents, and letters. The carmine-cochineal insect also thrived in the Americas. Native Americans throughout the north and south Americas used to pluck the insect of cacti leaves and dry them. They would then extract the pigment to use in dyes for tapestries and clothing. On a trip through Colca Canyon in Peru, I had actually seen the insects set out on mats to dry in the sun near an indigenous settlement. On some winter nights after I discovered Zecchis, and after I had purchased the appropriate items to accompany my ink, I chose to stay in. I would sit at the oak desk with dip pens, quills, jars of ink, textured paper and a computer full of quotes and prose to copy and music to listen to. I could excuse the fact that it seemed like an entirely pointless pursuit by recognizing that process provided a meditative refuge. Plus now I felt I was participating in the long narrative of languages history.

Italic, gothic, or uncial (a medieval script) alphabet forms flowed cautiously from of my hand as I attempted to keep my rhythm and slant consistent. Florence is famous for resurrecting Roman and Greek knowledge and culture after the Middle Ages. So many statues and books and ideas that had once been considered obsolete have reared their heads from the garbage heap of defunctness in this town. The ink and my craft had done their time on the heap too. On a smaller scale, The Zecchis did many artists what the Medicis did for civilization. Leave it to the Renaissance town to revive what was defunct in me too.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Paalen Life and Work: I. Forbidden Land: The Early and Crucial Years 1905 - 1939Von EverandPaalen Life and Work: I. Forbidden Land: The Early and Crucial Years 1905 - 1939Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Collected Novels Volume One: Chamber Music and The LadiesVon EverandThe Collected Novels Volume One: Chamber Music and The LadiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Notebooks of Honora Gorman: Fairytales, Whimsy, and WonderVon EverandThe Notebooks of Honora Gorman: Fairytales, Whimsy, and WonderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interior Design Philosophy Gives "Carte Blanche" to Alain Pittet - Private View: Bibliotheca MirabilisVon EverandInterior Design Philosophy Gives "Carte Blanche" to Alain Pittet - Private View: Bibliotheca MirabilisNoch keine Bewertungen

- A History of Story-telling: Studies in the development of narrativeVon EverandA History of Story-telling: Studies in the development of narrativeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Top 10 Short Stories - The Edwardian Ghost StoryVon EverandThe Top 10 Short Stories - The Edwardian Ghost StoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- European Trash (Fourteen Ways to Remember a Father)Von EverandEuropean Trash (Fourteen Ways to Remember a Father)Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Hare With The Amber EyesDokument12 SeitenThe Hare With The Amber EyesPierfranco Minsenti100% (3)

- Demoniality or Incubi and SuccubiDokument72 SeitenDemoniality or Incubi and SuccubiMarcus TremblayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Death of PietyDokument10 SeitenThe Death of PietyPaulina EsaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiments in Ethnographic WritingDokument24 SeitenExperiments in Ethnographic WritingKarina ArreolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dead in Their Vaulted Arches by Alan Bradley (Excerpt)Dokument18 SeitenThe Dead in Their Vaulted Arches by Alan Bradley (Excerpt)Random House of Canada100% (1)

- The Hare With Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal Reading GuideDokument12 SeitenThe Hare With Amber Eyes by Edmund de Waal Reading GuideRandomHouseAU100% (1)

- Philip Guston - TalkingDokument7 SeitenPhilip Guston - TalkingdijaforaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jacomo Caracci Pontorno PDFDokument518 SeitenJacomo Caracci Pontorno PDFGuilhermeSarmiento100% (2)

- Anatole France The Mind and The Man.Dokument254 SeitenAnatole France The Mind and The Man.padmaja_v100% (1)

- Barbie Q by Sandra CisnerosDokument4 SeitenBarbie Q by Sandra CisnerosMa Keneth Gabasa Laurentino100% (1)

- Mark On The WallDokument13 SeitenMark On The WallWiveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview With Author Sandra CisnerosDokument11 SeitenInterview With Author Sandra CisnerosCecilia KennedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letters From The Library (II)Dokument56 SeitenLetters From The Library (II)Edgardo CivalleroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Heart of A Living ThingDokument23 SeitenThe Heart of A Living ThingPatrik ŠekutorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Portable Church - The LinksDokument12 SeitenThe Portable Church - The LinksannettegulickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Julie LluchDokument4 SeitenJulie LluchArmando Razon Jr.100% (2)

- Capital To Have Four More Socio-Cultural Centres - Delhi - Hindustan TimesDokument7 SeitenCapital To Have Four More Socio-Cultural Centres - Delhi - Hindustan TimesDIVYANoch keine Bewertungen

- Books For WritersDokument2 SeitenBooks For Writerstiarneym100% (1)

- Reading Rocks in Rockford 2019Dokument3 SeitenReading Rocks in Rockford 2019PR.com100% (2)

- The Marlborough Public Library 1870 To 2010 - in Commemoration of The 350th Anniversary of The Founding of MarlboroughDokument20 SeitenThe Marlborough Public Library 1870 To 2010 - in Commemoration of The 350th Anniversary of The Founding of MarlboroughLee WrightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secrets of Successful WritingDokument41 SeitenSecrets of Successful WritingEmma Leer100% (2)

- Mina Bloom ResumeDokument1 SeiteMina Bloom ResumeMina BloomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cae 1 Test 1: Paper 2 WritingDokument22 SeitenCae 1 Test 1: Paper 2 WritingHanhNguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Definition of MagazineDokument2 SeitenDefinition of MagazineJena Javier100% (1)

- MUS 2 Referencing SystemDokument4 SeitenMUS 2 Referencing SystemJuan Sebastian CorreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (James B. Meek) Art of Engraving A Book of Instru PDFDokument208 Seiten(James B. Meek) Art of Engraving A Book of Instru PDFSabrina Anabel VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- UK Fashion Passion and InfluenceDokument14 SeitenUK Fashion Passion and InfluenceBogdan ChirițăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation and Experiment in English Modernist FictionDokument5 SeitenInnovation and Experiment in English Modernist FictionUngureanu IulianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yellow JournalismDokument4 SeitenYellow JournalismemtiazemonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test, PassiveDokument1 SeiteTest, PassiveMirosaki SakimiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of BooksDokument8 SeitenHistory of BooksZoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tribnation 2Dokument1 SeiteTribnation 2Chicago TribuneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Divya BhaskerDokument50 SeitenDivya BhaskerPrs JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Polytechnic University of The Philippines Taguig City CampusDokument4 SeitenPolytechnic University of The Philippines Taguig City CampusRoxane Rivera100% (2)

- A Numismatic Bibliography of The Far East: A Check List of Titles in European Languages / by Howard Franklin BowkerDokument148 SeitenA Numismatic Bibliography of The Far East: A Check List of Titles in European Languages / by Howard Franklin BowkerDigital Library Numis (DLN)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cat in The Rain: Individuality: U.S. Americans Are Encouraged at An Early Age To Be Independent andDokument3 SeitenCat in The Rain: Individuality: U.S. Americans Are Encouraged at An Early Age To Be Independent andKrizza Marie Maglanque BatiNoch keine Bewertungen

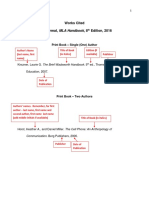

- Works Cited MLA Format, MLA Handbook, 8 Edition, 2016: Print Book - Single (One) AuthorDokument12 SeitenWorks Cited MLA Format, MLA Handbook, 8 Edition, 2016: Print Book - Single (One) AuthorhahjahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media Entertainment ListDokument444 SeitenMedia Entertainment Listjagrati malhotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbal Lang Dev Scale (Mecham, 1958)Dokument2 SeitenVerbal Lang Dev Scale (Mecham, 1958)monica_sagadNoch keine Bewertungen

- HISTORY OF THE PRINT INDUSTRY IN THE PHILIPPINESDokument11 SeitenHISTORY OF THE PRINT INDUSTRY IN THE PHILIPPINESTrisha LucarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instituteof: MoviesDokument73 SeitenInstituteof: MoviesStaten Island Advance/SILive.com100% (4)

- Proiectare Unei Unitati de Invatare La Limba Engleza Clasa A Ixa English My LoveDokument4 SeitenProiectare Unei Unitati de Invatare La Limba Engleza Clasa A Ixa English My LoveCamelia Mihaela GheorghitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Language (English Paper - 1) PDFDokument7 SeitenEnglish Language (English Paper - 1) PDFAyana DeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media Matrix Sexing The New RealityDokument224 SeitenMedia Matrix Sexing The New RealityMalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chi Rho - A LegacyDokument2 SeitenChi Rho - A LegacyRoxy GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen