Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Nature and Meaning of The Legal Research

Hochgeladen von

denisedianeOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Nature and Meaning of The Legal Research

Hochgeladen von

denisedianeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

NATURE AND MEANING OF THE LEGAL PROFESSION Wade, Public Responsibilities of the Learned Professions 21 Louisiana Law Review

130, 1960.

I What do we mean when we speak of the learned professionals? Ordinarily we think we are referring to certain common callings of a traditionally dignified character. We think of law, medicine, the ministry and teaching. The concept of learned professionals developed during the middle ages. It came in with the rise of the universities. They had a faculty of arts, and a faculty of theology, law and medicine. Teachers, church officials, lawyers and physicians received prolonged formal training, and after they had completed this training they constituted a class apart. Since that time, there has been a consistent viewpoint that training is necessary to admission to a learned profession, and that the professions are based on an intellectual technique. Sometimes this training is prescribed by the state. That state licenses the admission to the particular learned professions, all that is except ministers, for reasons which are obvious. The control of the state, however, in large measure makes use of the facilities of universities and colleges. State licensing has come about gradually through standards set up by professional organizations. This suggests a second attribute of the learned professions: organization. In the beginning these organizations or associations were like guilds. Now they have a broader function. Lawyers and doctors and to some extent, teachers have through their associations set up code of ethics- codes that are taught by precept and example and made effective by the discipline of an organized profession. To some extent these associations have engaged in protective activities. But this should be a secondary objective. The organizations exist primarily for the advancement of medicine, justice or teaching, not of the individual members, as in the case of trade unions. The third attribute of a learned profession is that its numbers are dedicated to a spirit of public service. Gaining a livelihood is incidental. A professional man offers a certain service and he confers the same diligence and quality of service whether he is paid or not. The lawyer or doctor does not patent his discoveries or exploit them for his personal use, but makes them known to the profession and to the public in general. He practices preventive medicine and law. He does not advertise or compete for customers. He does not seek to create a demand for his services in the fashion that businessman does. To summarize, I quote the definition of Dean Roscoe Pound. A profession is a group of men pursuing a learned art *** in the spirit of a public service. Now in treating the public responsibilities of a member of the learned profession, I think we can consider his relationship (1) to his clientele, (2) to his profession, and (3) to the public in general.

II First we must consider the responsibilities owed to the clientele. The word clientele is a broad, general one. There are specific terms in which are used in connection with each of the professions: lawyer- client, physician-patient, teacherpupil, and minister-church member. Note that there is always a relationship, It is usually contractual, almost a status. The parties to this relationship are not dealing with each other at arms length. There is a relationship of trust and confidence . This is not just a factual relationship; it is imposed as a matter of law, creating fiduciary obligations. To say this in Latin as

members of the learned profession at one time were inclined to do, uberrima fides is required. The professional man is not liable only for outright fraud; his position gives him an opportunity for domination and undue influence, and he is liable for the exercise of these in an improper fashion. He must be frank and open in his dealings with his client. He cannot have any interests of his own, cannot be in a position involving a conflict of interests. If he makes a personal gain through any improper interest, he hold in it trust for the benefit of his client. These are the legal responsibilities. Something more needs to be said here. Perhaps it is suggested by the phrase family doctor or family lawyer. With the increasing peace of the modern times, lack of time and specialization, impersonality and business methods have set in. Practice becomes more like a business; the understanding and tact and sympathy and patience and considerateness which formerly existed are often missing. These qualities, too, a doctor or lawyer owes to his patient or client. III Let me now speak of the responsibilities owed to the profession. All true professional men recognize that they owe a duty to their profession. It is their responsibility to seek to improve it. In my own profession, law, we recognize that there is a continuing duty to seek to improve the administration of justice, to better the procedural rules and substantive rules, to find means to eliminate delay in court, to find better means of selecting judges, of improving the legislative process. With the professions in general there is duty to engage in research, to write articles and treatises. There is the duty to continue the education which was started in the university. The investment by the university and those who have supported it can be justified only if we continue our self- education on a level which compares favorably with our formal instruction. We have a particular duty to promote continuing professional education and to attend institutes and symposia, and not just those which are bread-and-butter ones, but also those which are more cultural in nature. (a) At least six (6) hours shall be devoted to legal ethics equivalent to six (6) credit units. (b) At least four (4) hours shall be devoted to trial and pretrial skills equivalent to four (4) credit units. (c) At least five (5) hours shall be devoted to alternative dispute resolution equivalent to five (5) credit units. (d) At least nine (9) hours shall be devoted to updates on substantive and procedural laws, and jurisprudence equivalent to nine (9) credit units. (e) At least four (4) hours shall be devoted to legal writing and oral advocacy equivalent to four (4) credit units. (f) At least two (2) hours shall be devoted to international law and international conventions equivalent to two (2) credit units. (g) The remaining six (6) hours shall be devoted to such subjects as may be prescribed by the MCLE Committee equivalent to six (6) credit units.

There is a duty to know and to comply with the codes of ethics and to realize the problems that are involved. There is the more difficult duty of seeking to enforce the ethical codes with other members of the profession. This is a responsibility we too often ignore and yet it is so important that it could be the sole topic of this talk and still justify the title. Somewhat related here is the responsibility which arises when a client or a patient seeks to bring a negligence action against a lawyer or a doctor. Many of these actions may be unjustified, and a lawyer owes the duty to his own profession and his fellow profession of investigating carefully before taking the suit. But some are justified. A lawyer distinctly owes the duty to take a case if he concludes it is justified. And the doctor should be available to testify as a witness

for a plaintiff. A so-called conspiracy silence in some areas has done much to impair relations between the professions and the position of the professions in the public mind. The professional man should be ready to provide services to the poor without insisting on fee. We afford justice, health, education, and spiritual well being to all our people. None of these can be rationed, or made available only to those who can pay for them. We should be also be ready to take the lead in making it possible for an impecunious youth to become a member of the profession. Scholarships for study are vitally needed. IV Let me now consider the responsibilities owed to society, to the public in general. I can start this by stating on obvious truth. The members of the learned professions owe the duties which are common to those owed by the citizens as a whole. There is another responsibility, more or less peculiar to the members of the learned professions, or at least imposed upon them with greater force. This I should like to dwell upon at more length. It is the duty to supply intelligent, unselfish leadership to the forming of public opinion, and the determination of important issues. Democracy requires leaders, not in the authoritarian sense of having the power to command, but in the sense of being able to persuade others to follow. De Tocqueville, in his remarkably prescient analysis of democracy in America a century and a quarter ago, declared that lawyers and the influence they exerted were the most powerful existing security against the excesses of democracy, supplying the sobriety and stability which every good society requires. He might accurately have tbroadened this to include the other three learned professions. De Tocqueville suggested that they were the aristocracy of the democracy. The application here of the concept nobles oblige is obvious. In the case of the original ar istocracy, it was their authority which placed upon them the duty to wiled it in the general interest, rather than solely in their own interest. In the case of the member of a learned profession, it is his ability , his trainings, and his talents which palce on him an obligation to our society in general and to our governmental processes in particular. Every on to whom much is given, of him will much be required, and of him to whom men commit much they will demand the more. As a committee from the American Medical Association put it, Doctors, ignorant of history and the problems of society can (despite high professional skills) do more harm than other persons precisely because of their relations to their patients and the way they are regarded in the community. In other words, responsibility in the sense of duty to perform well flows from responsibility in the sense of the actual power to make or influence decisions. If we as members of the learned professions do have the responsibility to afford leadership in forming public opinion- constructive leadership- there are certain duties which accompany that certain responsibility. These are duties which we cannot delegate because of our busy lives. They can, , of course, be evaded, and unlike the duty to our clients, it is easy for us to evade them. The first of these duties is to be thoroughly aware of particular issues at various governmental levels- to seek to learn the facts and factors involved in them in a careful skeptical fashion. The second is to make wise decisions regarding these issues. What do the members of the learned professions do about these two duties? What do you do? Do you take time to peruse regularly several news media? Have you sought to evaluate the accuracy of each particular medium , its leanings, its tendency to color? Have you sought to identify your own prejudices and biases and to discount them as if they belonged to someone else when you reach a decision? Do you discount in the same way your own self-interests and those of your clients?

Are you open minded, careful to consider both sides of an issue, and even after reaching a decision, are you still ready to reassess its validity? These are some of the factors be taken into consideration in forming an opinion: the duty of a professional man is to form an objective opinion on public issues, unharnessed by his own needs and those of his clientele and those of his profession, although they are all entitled to some weight. This is half of the broad responsibility; the other half is to influence the opinions and actions of others. How to do it? There is no standard way. Some professional men will already be in positions of authority. Others should seek such positions- this responsibility should rest upon the conscience many us. Still others will be advisors to policy- makers or in a position to influence their action. And all of us Can have some influence upon public opinion in general. We can also influence the reality of the public discussion by assessing and questioning the accuracy of assertions made. Our training and experience have taught us to express ourselves well. Democracy must therefore have leadership. If we in the learned professions do not supply it., others will, and that leadership is not likely to be a wiser or as unselfish. If they do not supply it, our system may fail. Many democracies have failed. The system is by no means foolproof. COMMENT (1) There is no general agreement as to the essential elements which distinguish a professional from other callings. The following are the suggested as the more important considerations bearing on the question: (a) A profession involves the pursuit of a learned art of mastery of which requires training and superior intellectual ability. There are of course many other activities with similar requirements which are not professional but a calling which can be mastered without trainings and intellectual ability would not be a profession. (b) The services rendered are vital to society and are generally recognized to be so. Services not of social significance cannot qualify as a professional. But again, a calling may fulfill an important social need and yet not be a profession. The lawyers services qualify in this respect. Our economic, political, and social organization requires an extensive and complex system of laws regulating and controlling relations between individuals and between them and the state. It is not enough that these laws be made. They must be also be soundly and effective developed interpreted and applied. This is the essential function of the lawyer. It is through his advice, drafting of legal instruments, negotiations, settlement of disputes and representation in litigation that justice through law is primarily effectuated and applied to the affairs of men. (c) For the majority of the members of a profession, these services are offered to clients who employ them, usually for a fee. They are offered clients who employ them, usually for a fee. They are offered on a competitive, for-hire basis. They are the means by which lawyers, in competition with other lawyers, earn livelihood. (d) The relationship established is by and large a personal one. (e) The responsibility for securing these services to all who need them and in such manner that the public interest will be served is left to the profession itself. By and large, it is not enforced by controls external to the professional group. Codes of professional ethics serve this purpose. In Re Rothman 12, 12 N J 528 97 A. 2d 621, 1953 Chief Justice Vanderbilt observed: The canons of the professional ethics undertake to codify in convenient form the traditions and the practice that have been recognized all over the centuries as part of the common law with respect to the lawyers obligations to the courts

and to the administration of justice, to the public, and his clients, and to his profession and his fellow practitioners. They are as obligatory on him as if cast in statutory form, as indeed there are in large part in many states. Our citizens have the right to expect from the members of a learned profession who are granted by the state privilege to the practice of law that they in return for this privilege will live up to the standards long recognized at common law and in large part codified in the Canons of Professional Ethics . For the most comprehensive study of the subject of legal thics, see drinker, Legal ethics, 1953. Almost every bar association has a committee on legal ethics which renders opinions on questions of appropriate conduct sub mitted by practicing lawyers, considers complaints against individual lawyers and in appropriate cases, may initiate disciplinary proceedings against them. The most authoritative opinions are those rendered and published by the Committee on Professional Ethics of the American Bar Association. States with integrated bar associations frequently are also empowered to conduct hearings on charges of misconduct and t recommend appropriate disciplinary sanctions. Maclver, the Social Significance of Professional Ethics* The spirit and method of the craft, banished from industry, finds a more permanent home in the professions. Here still prevail the long apprenticeship, the distinctive training, and the small scale unit of employment and the intrinsic as distinct from the economic interest alike in the process and the product of the work. The sweep of economic evolution seems at first sight to have passed the professions by. The doctor, the lawyer, the architect, the minister of religion, remain individual practitioners, or at most enter into partnerships of two or three members. Specialization takes place, but in a different way, for the specialist in the professions does not yield his autonomy. He offers his specialism directly to the public and only indirectly to his profession. But this very autonomy is the condition under which the social process brings about another and no less significant integration. The limited corporations of the business world being thus ruled out, the whole profession assumes something of the aspect of a corporation. It supplements the advantage or the necessity of the small-scale, often the one-man, by concerted action to remove its natural disadvantage, the free play of uncontrolled individualism which undermines all essential standards. It achieves integration not of form but of spirit. Of this spirit nothing is more significant than the ethical code which it creates. There is in this respect a marked contrast between the world of business and that of the professions. It cannot be said that business has yet attained a specific code of ethics, resting on considerations broader than the sense of self-interest and supplementing the minimal requirements of the law. Such a code may be in the making, but it has not yet established itself, and there are formidable difficulties to be overcome. When we speak of business ethics, we generally mean the principles of fair play and honorable dealing which men should observe in business. Sharp dealing, unfair competition, the exaction of the pound of flesh, may be reprobated and by the decent majority condemned, but behind such an attitude there is no definite code which businessmen reinforce by their collective sense of its necessity and by their deliberate adoption of it as expressly binding upon themselves. There is no general brotherhood of businessmen from which the offender against these sentiments, who does not at the same time overtly offend against the law of the land, is extruded as unworthy of an honorable calling. There is no effective criticism which sets up a broader standard of judgment than mere success. If we inquire why this distinction should hold between business and professional standards the social significance of the latter is set in a clearer light. It is not that business, unlike medicine or law for example, lacks those special conditions which call for a code of its own. Take, on the one hand, the matter of competitive methods, it is a vital concern of business, leading to numerous agreements of all sorts, but these are mere ad hoc agreements of a particular nature, not as yet deductions from a fully established principle which business, as a self-conscious whole, deliberately and universally accepts. Take, on the other hand, such a problem as that of the duty of the employee to his workpeople. Is not this a subject most apt for the introduction of a special code defining the sense of responsibility involved in that relationship? But where is such a code to be found? The Ideal of Service

Something more than a common technique and a common occupation is evidently needed in order that an ethical code shall result. We might apply here the significant and much misunderstood comparison which Rousseau drew between the will of all, and the general will. In business we have as yet only the will of all, the activity of businessmen, each in pursuit of his own success, not overridden though doubtless tempered by the general will, the activity which seeks first the common interest. The latter can be realized only when the ideal of service controls the ideal of profits. We do not mean that businessmen are in fact selfish while professional men are altruistic. We mean simply that the ideal of the unity of service which business renders is not yet explicitly recognized and proclaimed by itself. It is otherwise with the professions. They assume an obligation and an oath of service. A profession, says the ethical code of the American Medical Association, has for its prime object the service it can render to humanity; reward or financial gain should be a subordinate consideration, and again it proclaims that the principles laid down for the guidance of the profession are primarily for the good of the public. Similar statements are contained in the codes of the other distinctively organized professions. The profession, says the proposed code of the Canadian legal profession, is a branch of the administration of justice and not a mere money - getting occupation. Such professions as teaching, the ministry, the civil service, and social work by their very nature imply like conceptions of responsibility. They imply that while the profession is of necessity a means of livelihood or of financial reward, the devoted service which it inspires is motivated by other considerations. In business there is one particular difficulty retarding any like development of unity and responsibility It may safely be said that so long as within the industrial world the cleavage of interest between capital and labor, employer and employee, retains its present character, - business cannot assume the aspect of a profession. This internal strife reveals a fundamental conflict of acquisitive interests within the business world and not only stresses that interest in both parties to the struggle but makes it impossible for the intrinsic pro-fessional interest to prevail. The professions are in general saved from that confusion, Within the profession there is not, as a rule, the situation where one group habitually employs for gain another group whose function, economic interest, and social position are entirely distinct from its own. The professions have thus been better able to adjust the particular interests of their members to their common interest and so to attain a clearer sense of their relationship to the whole community. Once that position is attained, the problem of occupational conduct takes a new form. It was stated clearly long enough ago by Plato in the Republic. Each art, he pointed out, has a special good or service. Medicine, for example, gives us heal th; navigation, safety at sea, and so on. * * * Medicine is not the artor profession-of receiving pay because a man takes fees while he is engaged in healing. * * * The pay is not derived by the several artists from their respective arts. But the truth is, that while the art of medicine gives health, and the art of the builder builds a house, another art attends them which is the art of pay. Th e ethical problem of the profession, then, is to reconcile the two arts, or, more generally, to ful fill as completely as possible the primary service for which it stands while securing the legitimate economic interest of its members, It is the attempt to effect this reconciliation, to find the due place of the intrinsic and of the extrinsic interest, which gives a profound social significance to professional codes of ethics. Responsibility to the Wider Community We need not assume that these codes originate from altruistic motives, nor yet condemn them because they protect the interest of the profession itself as well as various interests which it serves. To do so would be to misunderstand the nature of any code. An ethical code is something more than the prescription of the duty of an individual towards others; in that very act it prescribes their duty to him and makes his welfare too its aim, refuting the false dis-association of individual and the social. But the general ethical code prescribes simply the duties of the members of a community towards one another. What gives the professional code its peculiar significance is that it prescribes also the duties of the members of a whole group towards those outside the group. It is just here that in the past ethical theory and practice alike has shown the greatest weakness. The code has narrowed the sense of responsibility by refusing to admit the application of its principles beyond the group. Thereby it has weakened its own logic and its sanction, most notably in the se of national groups, which have refused to apply or even to relate their internal codes to the international world. The attempt of professional groups to

coordinate their responsibilities, relating at once the individual to the group itself to the wider community, marks thus an important advance. We must, however, admit that it is in this matter, in the relation of the profession as a whole to the community, that professional codes are still weakest and professional ethics least effectively developed. The service to the community they clearly envisage is the service rendered by individual members of the profession to members of the public. The possibility that there may still be an inclusive professional interest generally but not always economic one that at significant points is not harmonized with the community interest is nowhere adequately recognized. The problem of professional ethics, viewed as the task of coordinating responsibilities, of finding, as it were, a common center for the various circles of interest, wider and narrower, is full of difficulty and far from being completely solved. The magnitude and the social significance of this task appear if we analyze on the one hand the character of the professional interest and on the other the relation of that interest to the general welfare. Professional Interest and General Welfare Every organized profession avows itself to be an association existing primarily to fulfill a definite service within the community. Some codes distinguish elaborately between the various types of obligation incumbent on the members of the profession. The lawyer, for example, is declared to have specific duties to his client, to the public, to the court or to the law, to his professional brethren, and to himself. It would occupy too much space to consider the interactions, harmonies, and potential conflicts of such various duties. Perhaps the least satisfactory reconciliation is that relating the interest of the client to the interest of the public, not merely in the consideration of the particular cases as they arise but still more in the adaptation of the service to the needs of the public as a whole as distinct from those of the individual clients. Thus the medical profession has incurred to many minds a serious liability, in spite of the devotion of its service to actual patients, by its failure for so long to apply the preventive side of medicine, in particular to suggest ways and means for the prevention of the needless loss of life and health and happiness caused by the general medical ignorance and helplessness of the poor. In addition it must suffice to show that the conception of communal service is apt to be obscured alike by the general and by the specific bias of the profession. It is to the general bias that we should attribute such attempts to maintain a vested interest as may be found in the undue restriction of entrants to the profession undue when determined by such professionally irrelevant considerations as high fees and expensive licenses; in the resistance to specialization, whether of tasks or of men, the former corresponding to the resistance to dilution in the trade union field; in the insistence on a too narrow orthodoxy, which would debar from professional practice men trained in a different school; in the unnecessary multiplication of tasks, of which a flagrant example is the English severance of barrister and solicitor. Another aspect of the general bias is found in the shuffling of responsibility under the cloak of the code. This is most marked in the public services, particularly the civil service and the army and navyand incidentally it may he noted that the problem of professional ethics is aggravated when the profession as a whole is in the employ of the state. An official, says Emile Faguet in one of his ruthless criticisms of officialdom,9 is a man whose first and almost only duty is to have no will of his own. Danger of Specific Group Bias This last case brings us near to what we have called the specific bias of the profession. Each profession has a limited field, a special environment, a group psychology. Each profession tends to leave distinctive stamp upon a man, so that it is easier in general to distinguish, say, the doctor and the priest, the teacher and the judge, the writer and the man of science than it is to discern, outside their work, the electrician from the railwayman or the plumber from the machinist. The group environment creates a group bias. The man of law develops his respect for property at the risk of his respect for personal rights. The teacher is apt to make his teaching an over-narrow discipline. The priest is apt to underestimate the costs of the maintenance of sanctity. The diplomat may overvalue good form and neglect the penalty of exclusiveness. The civil servant may make a fetish of the principle of seniority, and the soldier may interpret morality as mere esprit de corps.

All this, however, is merely to say that group ethics will not by themselves suffice for the guidance of the group unless they are always related to the ethical standards of the whole community. This fact has a bearing on the question of the limits of professional self- government though we cannot discuss that here. Professional group codes are, as a matter of fact, never isolated, and thus they are saved from the narrowness and egotism characteristic of racial group ethics. Their dangers are far more easily controlled, and their services to society, the motive underlying all codes, vastly outweigh what risks they bring. They provide a support for ethical conduct less diffused than that inspired by nationality, less exclusive than that derived from the sense of class, and less instinctive than begotten of the family. As they grow they witness to the differentiation of community. Their growth is part of the movement by which the fulfillment of function is substituted as a social force for the tradition of birth or race, by which the activity of service supersedes the passivity of station. For all their present imperfections these codes breathe the inspiration of service instead of the inspiration of mere myth or memory. As traditional and authoritative ethics weaken in the social process, the formulated in the light of function bring to the general standard of the community a continuous and creative reinforcement. Teaching Law as a Social Science* Pacifico A. Agabin** I. INTRODUCTION Before the author was appointed Dean of the U.P. College of Law, University of the Philippines President Jose V. Abueva gave him the rare opportunity to write his philosophy of legal education into the guiding principles of the College as Chairman of the Reorganization Committee of the University of the Philippines Law Complex. After several hearings and meetings, the committee, composed of nine members from the law faculty, the law alumni, the administrative staff, and the students, came up with the following statement of guiding principles which was later approved by the Board of Regents: 1. The study and teaching of law must be integrated with the social sciences. It1 is only thus that law can be viewed as part of the social process, that is, as a system for the making of important decisions by society. 2. Training in the Law Complex must be training in the public interest: it must be a continuous, conscious and systematic effort at policy decision-making, where important values of a democratic society are distributed and shared. 3. The College of Law should aim to train lawyers who are not only superior craftsmen but also socially-conscious leaders who would be more interested in promoting the public interest than in protecting the private property rights of individual clients. 4. To develop the professional skills of students and lawyers, the College of Law should not only impart substantive knowledge but it should also develop the basic working skills necessary for successful law practice, like analytical skills, communication skills, negotiating skills, as well as awareness of their institutional and non-legal environment. 5. In order to enhance training for professional competence, legal education offered by the College of Law should be woven around a sense of Purpose, as it is an accepted pedagogic truth that a sense of purpose eases the path of learning Thus, students of law will more easily master legal doctrines and principles if they see these in relation to a given purpose and as tools for problem solving, instead of just viewing them as diverse and disoriented rules and doctrines existing in a vacuum. There was little or no politics in the framing of these guiding principles. There could not have been much opportunity anyway, since the law creating the Law Complex mandates it to be dedicated to teaching, research, training, information and legal extension services to ensure a just society. It shall be responsive to the challenges of social change, and shall be relevant to the growing legal and other law related needs of the Filipino people. II. IS THE CASE METHOD IN LAW STUDY A SCIENCE? While there was no Opposition in theory to the teaching of law as part of the social sciences, the statement flies in the face of reality.

It also prescribes a method of teaching that departs radically from the method Presently used in the College of Law, which is the case method. In fact, the structure and content of the law curriculum is hardly different from that employed when the College was first founded in 1911. The teaching method harks back to 1870 when Christopher Langdell of the Harvard Law School introduced the case method of law study. The Philosophy behind the case method is stated by Langdell thus: Law Considered as a science, consists of certain principles or doctrines... the growth of which is to be traced in the main through a series of cases; and much the shortest and the best, if not the only, way of mastering the doctrine effectively is by studying the cases in which it is embodied. But the cases which are useful and necessary for this purpose at the present day bear an exceedingly small proportion to any that have been reported. The vast majority are useless, or worse than useless, for any purpose of systematic study... It seems to me, therefore, to be possible to take such a branch of law as Contracts, for example, and without exceeding comparatively moderate limits, to select, classify and arrange all the cases which had contributed in any important degree to the growth, development or establishment of any of its essential doctrines. The Langdellians, eager to jump onto the bandwagon of science hat was then starting to become intellectually fashionable, advanced the theory that law study was science, arrived at through the inductive method. Under this system, wrote one of his disciples, the student must look upon the law as science consisting of a body of principles to be found in adjudged cases, the cases being to him what the specimen is to the geologist.13 It was in the United States, from 1870 to about the 1920s, that the science of the law meant the doctrinal analysis of cases on a given subject. Papers on law were treatises analyzing and even critiquing legal principles laid down in leading cases. But at least by 1870 the study of law had latched on to the scientific method, and the law professors shifted their allegiance from mysticism to science. Before 1870, the study of law was undertaken by a priestly class of scholars and based on a tradition of mysticism. This tradition was derived from the Continental universities in Europe which, in turn, inherited it from the medieval monks. Thus, law study was a ritualistic and mystical exercise which consisted of memorizing codal provisions and laws taught ex cathedra by monkish professors. The relationship between law and religion was emphasized to compel obedience to law through threats of hellfire and brimstone. It is no wonder that one realist professor branded this approach to law as transcendental nonsense. The case method is coupled with the so-called Socratic dialogue between teacher and student. Here the professor leads the student to elicit the principle from each assigned case by asking the latter about the facts of the case, the position taken by the litigants, the issues before the court, the ruling and the reasoning employed by the judge. A famous professor, George Stigler, had observed that originally, the Socratic method involved a teacher sitting on one end of a log, and talking with a student at the other end. But sometimes it is more productive, according to Stigler, to sit on the student and talk to the log. Langdell thought very strongly that a law school should become part of a university and not remain a separate institution. [If] printed books are the ultimate sources of all legal knowledge if every student who would obtain any mastery of the law as a science must resort to these ultimate sources, and if the only assistance which it is possible for the learner to receive is such as can be afforded by teachers who have travelled the same road before him then a university, and a university alone, can afford every possible facility for teaching and learning law. Note that Langdells reason for integrating law study into the university has very little to do with the role of law in the social sciences. While his inductive method placed law at par with the other sciences then emerging in the sense that the study of law became part of the grand experiment in education and learning, it has not located law in the company of the more empirical social sciences. For the fact is that Langdell did not for a moment look at law as part of the social sciences. He looked at law as a selfcontained and independent discipline, saying that unles s law was a package capable

of rational analysis within its own confines it has no business being in the university. It is surprising how an accomplishe d master of logic like Langdell could have committed this non sequitur. That is why there were skeptics who questioned Langdells assumptions. Thorstein Veblen, for one, remarked that law schools belong in the modern university no more than as a school of fencing or dancing. But the objections to the case method in law have nothing to do with the pragmatism of fencing or dancing schools. On the contrary the method is thought to be too abstract and intellectual, too preoccupied with the search for fundamental principles that would bring stability and certainty to the law, with little or no regard for its actual application in real life. And, of course, it has not departed from the Victorian worldview of the positivists that law, finding its basis in reason, is an independent and self-contained discipline unrelated to the other sciences. III. WHY APPROACH LAW AS A SOCIAL SCIENCE? It was the realist movement in law which delivered a signify cant blow to the case method in the arena of legal education. By the 1930s, the realists had come to realize that reason was not such a reliable guide to moral understanding nor a powerful guide to law. According to realists John Chipman Gray and Justice Holmes, the method isolated cases from their social and historical context and failed to take into account the factors that caused the evolution of legal principles. The realists considered law as a process of legal observation, comparison, and criticism instead of an exact science of value-free principles. The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience, said Justice Holmes. The thrust of the realist movement, insisting on scientific prediction of how judges would decide, moved law study closer to the social sciences. As Justice Holmes himself said: No one will ever have a philosophic mastery over the law who does not habitually consider the forces outside of it which have made it what it is. More than that, he must remember that as it embodies the story of the nations development through many centuries, the law finds its philosophy not in self-consistency, which it must always fail in so long as it continues to grow, but in history and the nature of human needs. As a branch of anthropology, law is an object of science; the theory of legislation is a scientific study. Furthermore, the case method of study had a very tenuous hold in civil law countries like the Philippines, except possibly in the University of the Philippines, not only because of the incompatibility of the academic approach with a system based primarily on legislation, but also for lack of materials. The expansion of the law as a result of the progressive movement dealt another blow to the case method, with the trend towards codification and the development of administrative law copied from Continental Europe. As observed by A.V. Dicey, Vinerian Professor of Law at Oxford and Langdells bulldog in England, the social justice movement which emerged at the turn of the century demanded legislation to change the common law so as to solve pressing social problems of society, and each law, in turn, gave rise to a new public opinion, which itself generated stronger demands for more radical legislation. In the universities of the Western Hemisphere, the social sciences may be going out of fashion. They have lost their interest and evangelical fervor, as Allan Bloom has put it.18 Where previously the social sciences, such as economics, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and political science, were august and imperial names in the realm of scientific knowledge, they are now pale shadows in the intellectual landscape, eclipsed by the second coming of the physical and natural sciences. The situation may be slightly different with law, for it was only recently that it has been discovered to be a social science. The stab of enlightenment suddenly hit jurists and law professors so hard that they have been goaded to call law the Queen of Social Sciences 19 in a spirit of partisan hyperbole characteristic of lawyers. One cannot advocate the teaching of law as a social science simply because it is the fad among the law schools in developed countries. It is time for the College of Law to break tradition and deviate from its hidden curriculum of producing an elite professional class catering to the needs of the establishment. The fact remains that in developing countries, especially those that have been colonized by

Western powers, laws have been imported wholesale by the colonial powers and thrust upon the subject people. Sometimes, the result is a gaping disparity between life and the law, between reality and rules. The laws that have been imposed by colonial authorities on the native peoples did not suit the latter. This is what happened in the Philippines and in some other countries. In the Philippines, there is an urgent need to approach law as a social science in view of our colonial past. Law in our country is of course a product of our history. We were colonized for 400 years, and the colonial powers imposed their laws upon us without regard to our customs and traditions as a people. Moreover, our law is written in a foreign language which the majority of our people do not understand. Since we lived under the Spanish rule for 350 years and under American rule for another 50 years, we have to re-examine the roots of our legal culture and see if it accords with the spirit of our people. The laws of any country are the product of its culture and its history; if these are merely imported wholesale into the country, they will not be an effective instrument for social control. The problem in social reform i proving the basic premises. It is in this area where the tools of the social sciences serve us in good stead, for they give us a good grasp on reality. It is only the methodology of the social sciences which can validate the social and political premises on which we base our conclusion that the law always lags behind social and economic development. If utilized properly, this methodology cuts through the fig leaf of legal fictions to reveal the revolting realities in the operation of laws. It is through empirical research that we pierce the veil of traditional legal rules to see if the implementation of laws leads to substantial justice or to injustice. It is only the expertise of the social Sciences which can strip our jurisprudence of its cherished myths adopted from foreign sources and bring it down to earth in touch with the mores of the people whose behavior it seeks to regulate or control. Knowing how laws stand in the way of social reform, or how far it has lagged behind economic and political developments, we can propose adjustments to effect social change. If one perceives that people empowerment is just an empty shibboleth, one can propose legal reform to afford greater distribution of political power. If one sees the effectiveness of groups against the warloads and vested interests, then knowledge of the law can be harnessed by nongovernmental groups to access governmental power or to influence the private business sector. lV. USING THE TOOLS OF SOCIAL SCIENCE IN LAW This approach to the law views it as a multi-disciplinary phenomenon historical, social, economic, political, religious, psychological and anthropological. This will not, of course, merge the study of law with that of the social sciences, for law does not have the precision of methodology that characterizes the other social sciences. But it will broaden the study of law so that it will not be presented as an independent branch of study. Law will cease to exist in a vacuum, and it will be studied with the best insights that the related behavioral sciences can offer. This method will also emphasize to the law student the role of law in the social order, its functions of defining interpersonal relationships and of redefining such relationship in the light of social changes, the legal institutions created for such changes, and how society adapts to social change. This will also give the study of the law a double-focus, so that the students will study not only the tools of the law but also its ends. This will underline the study of the values underpinning the legal system and the relationship of the means to the ends. While the study of values will reveal the lack of precision of the legal method, it will shed light on the ends sought to be attained by the law in the constant tension between stability and change, freedom and security, history and logic, ideal justice and justice in practice." A professor advocating this approach lists seven central problems which circumscribe the main subject matter of the study of law in relation to the social sciences: 1. The relation between law and social type; 2. The functions of law in society; 3. The modes of operation of law; 4. The creation, development, and evolution of law;

5. Law, culture, and the main social institutions; 6. Law and social change; and 7. Law and aw personnel. This list of problems is comprehensive enough to show how law would relate to the social sciences of anthropology, sociology, political science, psychology, and economics. These general prescriptions for the marriage of law and the social sciences, although seemingly elementary, are difficult to achieve. First, members of the law faculty will have to acquaint themselves with the tools of the related social sciences, which will take at least a generation of teachers. Second, the law school must expand beyond mere teaching and research and go into outreach and extension services. Its faculty must be endowed with the necessary empirical outlook and experience which they will transmit to their students.

result is a gaping disparity between life and the law, between reality and rules. The laws that have been imposed by colonial authorities on the native peoples did not suit the latter. This is what happened in the Philippines and in some other countries. In the Philippines, there is an urgent need to approach law as a social science in view of our colonial past. Law in our country is of course a product of our history. We were colonized for 400 years, and the colonial powers imposed their laws upon us without regard to our customs and traditions as a people. Moreover, our law is written in a foreign language which the majority of our people do not understand. Since we lived under the Spanish rule for 350 years and under American rule for another 50 years, we have to re-examine the roots of our legal culture and see if it accords with the spirit of our people. The laws of any country are the product of its culture and its history; if these are merely imported wholesale into the country, they will not be an effective instrument for social control. The problem in social reform i proving the basic premises. It is in this area where the tools of the social sciences serve us in good stead, for they give us a good grasp on reality. It is only the methodology of the social sciences which can validate the social and political premises on which we base our conclusion that the law always lags behind social and economic development. If utilized properly, this methodology cuts through the fig leaf of legal fictions to reveal the revolting realities in the operation of laws. It is through empirical research that we pierce the veil of traditional legal rules to see if the implementation of laws leads to substantial justice or to injustice. It is only the expertise of the social Sciences which can strip our jurisprudence of its cherished myths adopted from foreign sources and bring it down to earth in touch with the mores of the people whose behavior it seeks to regulate or control. Knowing how laws stand in the way of social reform, or how far it has lagged behind economic and political developments, we can propose adjustments to effect social change. If one perceives that people empowerment is just an empty shibboleth, one can propose legal reform to afford greater distribution of political power. If one sees the effectiveness of groups against the warloads and vested interests, then knowledge of the law can be harnessed by nongovernmental groups to access governmental power or to influence the private business sector. lV. USING THE TOOLS OF SOCIAL SCIENCE IN LAW This approach to the law views it as a multi-disciplinary phenomenon historical, social, economic, political, religious, psychological and anthropological. This will not, of course, merge the study of law with that of the social sciences, for law does not have the precision of methodology that characterizes the other social sciences. But it will broaden the study of law

so that it will not be presented as an independent branch of study. Law will cease to exist in a vacuum, and it will be studied with the best insights that the related behavioral sciences can offer. This method will also emphasize to the law student the role of law in the social order, its functions of defining interpersonal relationships and of redefining such relationship in the light of social changes, the legal institutions created for such changes, and how society adapts to social change. This will also give the study of the law a double-focus, so that the students will study not only the tools of the law but also its ends. This will underline the study of the values underpinning the legal system and the relationship of the means to the ends. While the study of values will reveal the lack of precision of the legal method, it will shed light on the ends sought to be attained by the law in the constant tensio n between stability and change, freedom and security, history and logic, ideal justice and justice in practice." A professor advocating this approach lists seven central problems which circumscribe the main subject matter of the study of law in relation to the social sciences: 1. The relation between law and social type; 2. The functions of law in society; 3. The modes of operation of law; 4. The creation, development, and evolution of law; 5. Law, culture, and the main social institutions; 6. Law and social change; and 7. Law and aw personnel. This list of problems is comprehensive enough to show how law would relate to the social sciences of anthropology, sociology, political science, psychology, and economics. These general prescriptions for the marriage of law and the social sciences, although seemingly elementary, are difficult to achieve. First, members of the law faculty will have to acquaint themselves with the tools of the related social sciences, which will take at least a generation of teachers. Second, the law school must expand beyond mere teaching and research and go into outreach and extension services. Its faculty must be endowed with the necessary empirical outlook and experience which they will transmit to their students. While the social sciences are concerned with the behavior of individuals and groups in society, law is concerned with the control and regulation of human conduct and the promulgation of rules to guide behavior in socially beneficial ways. The approach of the social sciences is thus different from that of law. For example, the clinical method or even the case method of law teaching focuses on the particulars of a case at hand. On the other hand, the social sciences focus on the statistics of a class of cases which are in some important ways similar to a particular case at hand. The law teacher looks at the trees; the social scientist looks at the forest. It is easy to guess who will mistake the trees for the forests. Even someone who does not profess to be a social scientist, Vice-President Joseph Estrada, proved to be more adept in following the advice of Felix Cohen who suggested that legal scholars should use statistical methods in analyzing and predicting judicial behavior. Thus, Vice-President Estrada beat the Supreme Court in uncovering the activities of the magnificent seven trial judges in the Makati Regional Trial Court by studying the pattern of judicial decisions in prohibited drug cases and observing the consistency of exonerations of the accused. He saw the big picture because he did not concentrate on the minute details of each case. The most popular example of the use of social science data is the case of Brown v. Board of Education. The issue was complex: Does the segregation of public school children solely on the basis of race deprive them of equal educational opportunities? The U.S. Supreme Court resorted to psychological data and found that: (1) there are psychological harms to black schoolchildren in a segregated environment; (2) there are certain intangible factors which produce superior learning environment in integrated schools; and (3) public schools play a critical role in contemporary society.

The use of field experiments in law could demolish legal assumptions which do not hold water, or establish new factual bases for rule-making. For example, we can question the efficacy of the adversarial system as a means of resolving disputes in the Philippines. The field experiment was used in a project on court referral for mediation conducted last year by the College of Law under the leadership of Professor Alfredo F. Tadiar. This project was undertaken to help the judiciary reduce its case backlog, which was 153,002 as of 1991. Two research sites, one urban and one rural, were selected to represent two social settings for the project. Participating courts were selected, mediators were appointed, and litigants were apprised of the experiment. The experiment was conducted by the project staff for about one year to determine the feasibility of mediation as a mode of alternative dispute resolution. Actual mediation proceedings were conducted regularly by the trained mediators. Of the 236 cases referred for mediation in the provincial project site, 71 were settled. 157 were returned, and 8 were dismissed, showing a success rate of 3 1.14%. In the urban project site, however, of the 17 cases referred, only 2 cases were settled and 15 returned. The following conclusions were arrived at: 1. Mediation is more feasible in the provincial areas than in the urban areas. 2. Litigants usually defer to the mediators age, rank or status in the community. 3. Retired officials make ideal mediators. 4. Elderly women make good mediators. 5. Money claims and those arising from contracts are most susceptible to mediation. 6. Consensus-building is an important part of the mediation process. After the experiment, the College proposed to the Supreme Court an amendment to the Rules of Court to provide for mediation of disputes in provincial areas and for the creation of special courts for disposition of money claims and actions based on contracts. It is always better to test the underlying assumptions of the laws with the standards of the empirical sciences. As two psychologists have noted: Traditionally, the behavioral technology of the law is laid down in legislation in civil law countries and in precedents in common law countries. . . Underlying these rules are assumptions of how individuals behave and how their behavior can be regulated. Since these assumptions are about the behavior of individuals, they are available for empirical research and testing. . . Altogether, however, only scattered and isolated assumptions of the law are tested, usually aiming at direct application in the courtroom. V. EMPIRICISM AND SOCIAL VALUES IN LAW One cannot, however, be so brash as to advocate the teaching of law completely by social science methods. This cannot be done for two reasons. First, the style and form of the current national bar examinations would not permit this, such examinations being a test of the students knowledge of legal doctrines. Se cond, it would be inconsistent with the nature of the law itself, which cannot be studied totally free from values and morals. Law is essentially normative, and a study of law delves into policy considerations behind the law. It cannot be limited by the methodology of value-free empiricism in the social sciences, if we define empiricism in the context of morals and politics. Law must go beyond knowledge gathered by the senses; it must be both descriptive and prescriptive. And there are strong pressures for law reform that impinge on law schools, especially on state-supported institutions. One example is the clinical legal education program. As pointed out by the president of Rutgers University, Professor Edward Bloustein, it was the moral unease of the 1960s and its search for political and social relevance that caused the revival of the clinical legal education program.26 The palpable objective of the program was to extend the law school s responsibilities to society and to decrease the traditional emphasis on preparing students for corporate practice. With respect to the legal aid clinic of the UP College of Law, its objectives are just as sublime: (1) to provide free legal serv ices to those who cannot afford them; (2) to provide law interns practical experience and learning opportunities from actual

handling of problems albeit confined to those faced by the poor; (3) to conscienticize them to the plight of the poor and oppressed sectors in society; (4) to help improve the administration of justice by filing test cases; and (5) to assist in law reform activities. The clinical method of legal education compels law students to focus on the judicial and administrative process and to apply scientific methods to the making and prediction of decisions. Here the students realize that there is a necessity for objective and external observation of the law, that empirical data could be used to assist in solving legal controversies, and that scientific techniques could be useful decisional methods. Ultimately, the conscienticized student who is exposed to reality will soon realize that the law can be a vehicle for social transformation. This method gives the student a proper understanding of the law in the light of social realities and in the context of the social environment. If the sees the law as laudable in theory but oppressive in practice, he will soon agitate for social change. The interface of the instruments of social science with values is most revealing in law because such instruments may demonstrate the inequity behind seemingly neutral legal constructs. For examples, the constitutional ideal of equality is certainly more than a cruel legal fiction in the light of economic realities in our society. As Anatole France once observed, the law, in all its majesty, prohibits the rich and the poor alike to beg on the streets and to sleep under the bridges. We do not even have to use the tools of social science to realize the irony of this delusion. In fact, the studies of social scientists show that in a society based on the principle of legal equality, the bulk of the people actually live under a regime of practical inequality. This is due to four factors working in favor of those who hold economic resources: (1) the different strategic position of the parties; (2) the role of lawyers; (3) the institutional facilities; and (4) the character istics of the legal rules favoring the haves. There are also intellectual traditions in the social sciences that can operate to stimulate social changes. Since legal training is steeped in the tradition of conservatism, dislike for differing views, and adherence to the status quo, it will hardly initiate social change. The masters tools will never dismantle the masters house, said Audrey Lorde. The atmosphere of testing as well as experimentation in the social sciences can be an inspiration for questioning in law that will lead to legal reform. Lawyers have much to learn from social change activists who often work outside the formal legal and political systems to create institutions to address what they think the law ignores, writes a law professor, Martha Minow.28 It is not only the methodology of the social sciences that is useful in law but even the concepts developed therein. For instance, if law is viewed in terms of power, then the students will get to know how law is linked to those who hold the levers of power in our society. This economic interpretation of law, as Dean Pound calls it, sees law in terms of a system of rule s imposed on men by the dominant class in a given society for the furtherance of their interests.29 So when it comes to the development of a corpus juris the ultimate question is what do the dominant forces of the community want and do they want it hard enough to disregard whatever inhibitions stand in the way, Justice Holmes once wrote to Dr. Wu.30 Seen in this light, law becomes a legalizing principle for the imposition of the wants of the dominant groups over the subject classes or the rest of society. For the ruling groups possess what Charles Merriam calls the monopoly of legality which enables them to utilize government tal systems of power for their own ends. In a mass democracy, the more numerous groups can also utilize law as an instrument to pass laws and codes for their own benefit. But first they must get to see law as an instrument of policy, not as an independent body of rules handed down by divine decrees or by the colonial powers. VI. SOCIAL SCIENCE OPPORTUNITIES INTHE CURRICULUM The main obstacle to the introduction of social science courses in the law curriculum in the Philippines is the qualifying bar examinations which are given by the Supreme Court every year. The bar examinations are a test of the students knowledge of the law in almost all areas, divided into subjects civil law, political law, international law, criminal law, commercial law, remedial law, taxation, labor law, and legal ethics.

From this doctrinal classification, one can readily see that law is seen as a set of enduring principles and rules existing independently of any social environment. It is seen as a determinate collection of rules divided as to subject, and which the student is expected to memorize and apply offhand if he is confronted with a legal problem. In view of this requirement of the Supreme Court, all law schools find it irrelevant or unnecessary to include the social study of law in their curricula. The emphasis of the law schools is in the pure study of law, underscoring the analysis and application of the internal structure of the hierarchy of rules classified according to subject. This is a serious obstacle to the development of the social study of law. Nonetheless, the College of Law of the University of the Philippines has a number of courses which focus on the relationship between law and society, and which utilize the tools of the social sciences. Required Courses In their first semester, incoming freshmen are required to take Legal History (Law 115), which traces the development of the worlds legal systems, including Philippine indigenous law, and emphasizes their relation to the basic legal institutions of the Philippines. The approach is a legal-historical one, illustrated by Von Savigny, Maine, and Allen, on the evolution of the law as a creation of cultural norms in a given society, depending on the familiarity of the professor with this approach. it is also in this area of study where the student will realize the relationship between law and social change. Legal Method (Law 116) deals with legal analysis, research techniques, rules of legal interpretation, and other aspects of the legal process. The course commences with deductive and inductive science as tools of legal analysis, then takes up the various research techniques, including those from the other social sciences, including use of empirical data, experiments, measurements, and behavioral analysis. In the second semester, freshmen are required to take Legal Theory (Law 117). This course discusses the main schools of jurisprudential thought, with emphasis on the philosophical influences on the varying conceptions of ideal law and natural law, and their impact on law as an instrument of procedural and substantive justice. This subject touches on the social sciences as ic discusses the various schools of jurisprudence and the different current of thoughts that gave rise to them, like sociology, anthropology, psychology, history, and political science. The study ofjurisprudence cannot be isolated from the social sciences, for these provide the basic ideological framework of the different legal theories. The Legal Profession (Law 120), is a study of the history, sociology, and development of the legal profession. It also discusses the role of the legal profession in Philippine society, and includes study of the Code of Professional Responsibility for lawyers. Emphasis is placed on the education and orientation of lawyers, their social prestige, their monopoly over judicial and legislative positions, their client, their political and other extralegal functions, and the subculture that they have developed.

In the third year, Medical Jurisprudence (Law 118), deals with the intersection between law and medicine. It is in this subject where law students become acquainted with the discipline of medical science. It is in the fourth year that the students take up Law Practicum 1 in the first semester and Law Practicum 2 in the second semester, where they are introduced to clinical legal education as described above. The students, under the direction of a supervisor, run the legal aid clinic and handle actual cases in the courts and in the administrative tribunals and agencies. The courses emphasize not only the different kinds of legal services like interviewing clients, drafting pleadings, trying

cases, negotiating, counseling, field observing, but also alternative means of dispute resolutions, like arbitration, mediation, and conciliation. The two clinical education courses count for 8 units. Elective Courses

What have been discussed above are core or mandatory subjects for all students. Some of the elective subjects, which may be taken by the second, third, and fourth year students for a total of 20 units, approach law from a social science viewpoint. Philippine Indigenous Law (Law 132), is an introduction to legal anthropology with an emphasis on indigenous Philippine custom laws and their relevance to the national legal order. The course also examines how the existing laws of the country affect the ethnic and cultural minorities in the Philippines. In this subject, the student will become aware of the relationship between law and culture and how far law is integrated or dissociated from the native culture. The student will also realize different types of systems of law depending on the different main types of societies. There is an elective course on Law and Poverty, which focuses on the political economy of development and traces continuities in the way power and thus often law and legal institutions have been used by dominant groups to, maintain and legitimize economic relations and the allocation of resources. It inquires into how the legal system contributes to conditions which misallocate resources and cause poverty and marginalization of people. The central problems of social justice, differential access to resources, and legal development are studied. The focus of the course is on the question on what legal resources might be provided to help the poor create self-reliant, participatory structures for their own development. A corollary problem is how structural barriers such as language, illiteracy and ignorance of legal procedures and ones basic rights under the Constitution and labor and social legislation, can be minimized so as to diminish differential access to resource allocation. A course on Human Rights is likewise offered. This course deals with the concept of human rights in different polities, and delves into the three major categories; of personal security, civil and political rights, and basic human needs. In this course, human rights is treated as a legal and social reality, and the constitutional guarantees protecting these rights are examined not only in theory but also in practice with the use of data on human rights violations gathered by non-governmental groups. VII. CONCLUSION Legal education must strive to train law students not only pure legal technicians but also as responsible citizens cognizant of the social, economic and political malaise gripping society at large. As a profession devoted to serving the public interest, a conscious effort must be made to prepare students of law as socially-relevant leaders for both the public and private sectors, whether as policy decision-makers of national standing or as private individuals serving their respective local communities. The teaching of law as a social science addresses this often overlooked dimension of legal training. Viewing law as part of the larger social firmament enables the young lawyer to meet the pressing needs of his society. For the greater challenge of the lawyer lies outside the courtroom rather than within it, where his legal training may be fully utilized to seek novel solutions responsive to the socio-economic problems plaguing his nation. Thus, a social science approach involves not only a continuing process of advancing societal goals but also a noble affirmation of the lawyers role as societys guardian of public interest. Questions:

(1) What is meant by profession in general? (2) What is your concept of the legal profession? (3) How do you distinguish the legal profession from other professions? (4) Why is law profession a social phenomenon? 5. Is compensation of a lawyer essential in the performance of his duty?

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Compare PD 1006, RA 7836 and RA 9293: Item P.D. 1006 R.A. 7836 RA 9293 ObservationDokument4 SeitenCompare PD 1006, RA 7836 and RA 9293: Item P.D. 1006 R.A. 7836 RA 9293 ObservationJerome Varquez84% (19)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Nursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1Dokument17 SeitenNursing Ethics and Jurisprudence 1dmsapostol100% (2)

- Legal Ethics NZDokument77 SeitenLegal Ethics NZShannon Closey100% (1)

- Accountability - Nursing Test QuestionsDokument25 SeitenAccountability - Nursing Test QuestionsRNStudent1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics & ProfessionalismDokument11 SeitenEthics & Professionalismsuzuchan100% (7)

- A Pocket Guide To Business For Engineers and SurveyorsDokument280 SeitenA Pocket Guide To Business For Engineers and SurveyorsZac Francis DaymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pictures of School BuildingsDokument2 SeitenPictures of School BuildingsdenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter HeadDokument2 SeitenLetter HeaddenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part I. Multiple Choice. Choose The Letter That Fits Best On The Given QuestionDokument2 SeitenPart I. Multiple Choice. Choose The Letter That Fits Best On The Given QuestiondenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apostasy in The Legal ProfessionDokument6 SeitenApostasy in The Legal ProfessiondenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint AffidavitDokument1 SeiteComplaint AffidavitdenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lengua EstofadoDokument2 SeitenLengua EstofadodenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest-Usa V Ah ChongDokument1 SeiteDigest-Usa V Ah ChongdenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

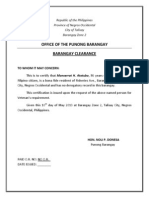

- Office of The Punong Barangay Barangay ClearanceDokument1 SeiteOffice of The Punong Barangay Barangay ClearancedenisedianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tolentino Vs Board of Accountancy FTDokument4 SeitenTolentino Vs Board of Accountancy FTNelia Mae S. VillenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Business Studies Notes CH01 Nature and Significance of ManagementDokument6 Seiten12 Business Studies Notes CH01 Nature and Significance of ManagementAshmita NagpalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rueda ST., Calbayog City 6710 Website: HTTP//WWW - Nwssu.edu - PH Email: Telefax: (055) 2093657Dokument2 SeitenRueda ST., Calbayog City 6710 Website: HTTP//WWW - Nwssu.edu - PH Email: Telefax: (055) 2093657paula marie pallonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profession Vs EthicsDokument7 SeitenProfession Vs Ethicssergiotp1003Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3462-Article Text-16515-1-10-20181112Dokument13 Seiten3462-Article Text-16515-1-10-20181112Marchelyn PongsapanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer Professional Bodies in NigeriaDokument4 SeitenComputer Professional Bodies in Nigeriakanny AkwaowoNoch keine Bewertungen

- COURSE SYLLABUS IN GE8-ETHICS, Second Semester, SY 2022-2023 - REVISION NO. 2022-01 COPY FOR ADOPTION-1Dokument23 SeitenCOURSE SYLLABUS IN GE8-ETHICS, Second Semester, SY 2022-2023 - REVISION NO. 2022-01 COPY FOR ADOPTION-1Duhreen Kate CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cayetano V MonsodDokument6 SeitenCayetano V MonsodGladys BantilanNoch keine Bewertungen