Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Syed Ahmad Islam

Hochgeladen von

music2850Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Syed Ahmad Islam

Hochgeladen von

music2850Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Javad-ud Daula, Arif Jang, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, KCSI (October 17, 1817 March 27, 1 898),

, also known as Syed Ahmed Taqvi, commonly known as Sir Syed, was an Indian educator and politician, and an Islamic reformer and modernist. Sir Syed pioneer ed modern education for the Muslim community in India by founding the Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College, which later developed into the Aligarh Muslim Universit y. His work gave rise to a new generation of Muslim entrepreneurs and politician s who composed the Aligarh movement to secure the political future of Muslims of India. In 1842, Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II revived upon Syed Ahmad Khan the title of Javad-ud Daulah, conferred upon Syed Ahmad s grandfather Syed Hadi by Emperor Shah Alam II in about the middle of the 18th century. The Emperor added to it the add itional title of Arif Jang. The conferment of these titles was symbolic of Syed Ahmad Khan s incorporation into the nobility of Delhi. Born into Muslim nobility, Sir Syed earned a reputation as a distinguished schol ar while working as a jurist for the British East India Company. During the Indi an Rebellion of 1857 he remained loyal to the British and was noted for his acti ons in saving European lives. After the rebellion he penned the booklet Asbab-eBaghawat-e-Hind (The Causes of the Indian Mutiny) a daring critique, at the time, of British policies that he blamed for causing the revolt. Believing that the fu ture of Muslims was threatened by the rigidity of their orthodox outlook, Sir Sy ed began promoting Western-style scientific education by founding modern schools and journals and organising Muslim entrepreneurs. Towards this goal, Sir Syed f ounded the Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875 with the aim of promoting s ocial and economic development of Indian Muslims. One of the most influential Muslim politicians of his time, Sir Syed was suspici ous of the Indian independence movement and called upon Muslims to loyally serve the British Raj. He denounced nationalist organisations such as the Indian Nati onal Congress, instead forming organisations to promote Muslim unity and pro-Bri tish attitudes and activities. Sir Syed promoted the adoption of Urdu as the lin gua franca of all Indian Muslims, and mentored a rising generation of Muslim pol iticians and entrepreneurs. Prior to the Hindi Urdu controversy, he was Interested i n the education of Muslims and Hindus both and this was the period in which Sir Syed visualised India as a beautiful bride whose one eye was Hindu and the other Muslim and due to this stance Sir Syed was regarded as a reformer and nationali st leader but there was a sudden change in his policies after the Hindi Urdu controv ersy. His Education and reformist policies became Muslim specific and he fought for the status of Urdu until his last breath.Maulana Hali, in his book Hayat-e-J aved, writes "One day as Sir Syed was discussing educational affairs of Muslims with Mr Shakespeare, the then Commissioner of Banaras. Mr Shakespeare looked sur prised and asked him, This is the first time when I have heard you talking specific ally about Muslims. Before this you used to talk about the welfare of the common Indians.'" He then told him, "Now I am convinced the two communities will not p ut their hearts in any venture together. This is nothing [it is just the beginni ng], in the coming times an ever increasing hatred and animosity appears on the horizon simply because of those who are regarded as educated. Those who will be around will witness it." Therefore in Pakistan, he is hailed as the father of Tw o Nation Theory and one of the founding fathers of Pakistan with Allama Iqbal an d Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Muslim reformer The motto of Aligarh University, Taught man what he did not know. (Qur'an 96:5) Through the 1850s, Syed Ahmed Khan began developing a strong passion for educati on. While pursuing studies of different subjects including European [jurispruden ce], Sir Syed began to realise the advantages of Western-style education, which was being offered at newly established colleges across India. Despite being a de

vout Muslim, Sir Syed criticised the influence of traditional dogma and religiou s orthodoxy, which had made most Indian Muslims suspicious of British influences . Sir Syed began feeling increasingly concerned for the future of Muslim communi ties. A scion of Mughal nobility, Sir Syed had been reared in the finest traditi ons of Muslim lite culture and was aware of the steady decline of Muslim political power across India. The animosity between the British and Muslims before and af ter the rebellion (Independence War) of 1857 threatened to marginalise Muslim co mmunities across India for many generations. Sir Syed intensified his work to pr omote co-operation with British authorities, promoting loyalty to the Empire amo ngst Indian Muslims. Committed to working for the upliftment of Muslims, Sir Sye d founded a modern madrassa in Muradabad in 1859; this was one of the first reli gious schools to impart scientific education. Sir Syed also worked on social cau ses, helping to organise relief for the famine-struck people of North-West Provi nce in 1860. He established another modern school in Ghazipur in 1863. Upon his transfer to Aligarh in 1864, Sir Syed began working wholeheartedly as a n educator. He founded the Scientific Society of Aligarh, the first scientific a ssociation of its kind in India. Modelling it after the Royal Society and the Ro yal Asiatic Society, Sir Syed assembled Muslim scholars from different parts of the country. The Society held annual conferences, disbursed funds for educationa l causes and regularly published a journal on scientific subjects in English and Urdu. Sir Syed felt that the socio-economic future of Muslims was threatened by their orthodox aversions to modern science and technology. He published many wr itings promoting liberal, rational interpretations of In face of pressure from r eligious Muslims, Sir Syed avoided discussing religious subjects in his writings , focusing instead on promoting education. On the pre-colonial system he said "The rule of the former emperors and rajas wa s neither in accordance with the Hindu nor the Mohammadan religion. It was based on nothing but tyranny and oppression; the law of might was that of right; the voice of the people was not listened to" (Bipan Chandra: India's struggle for in dependence).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Make It Short.: CoffeeDokument2 SeitenMake It Short.: Coffeemusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- 'I Don't Believe in Word Senses' - Adam KilgariffDokument33 Seiten'I Don't Believe in Word Senses' - Adam Kilgariffmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Computational Linguistics With The Zen Attitude: Department of Sanskrit StudiesDokument27 SeitenComputational Linguistics With The Zen Attitude: Department of Sanskrit Studiesmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Guardians of LanguageDokument462 SeitenGuardians of Languagemusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Inside The DramaHouseDokument238 SeitenInside The DramaHousemusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Getting To Be Mark TwainDokument146 SeitenGetting To Be Mark Twainmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human NatureDokument287 SeitenHuman Naturemusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Epic Traditions in The Contemporary WorldDokument291 SeitenEpic Traditions in The Contemporary Worldmusic2850100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Fatimid WritingsignsDokument126 SeitenFatimid Writingsignsmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Gender and SalvationDokument289 SeitenGender and Salvationmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Fieldwork Memoirs of BanarasDokument112 SeitenFieldwork Memoirs of Banarasmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Epic Traditions in The Contemporary WorldDokument291 SeitenEpic Traditions in The Contemporary Worldmusic2850100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- At The Heart of The Empire Indians and The Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian BritainDokument230 SeitenAt The Heart of The Empire Indians and The Colonial Encounter in Late-Victorian Britainmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Computational Theory MindDokument314 SeitenComputational Theory Mindmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Descartes ImaginationDokument263 SeitenDescartes Imaginationmusic2850100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Dangerous IntimacyDokument248 SeitenDangerous Intimacymusic2850100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Dangerous IntimacyDokument248 SeitenDangerous Intimacymusic2850100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- California Native StoriesDokument455 SeitenCalifornia Native Storiesmusic2850100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Authors of Their Own LivesDokument418 SeitenAuthors of Their Own Livesmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Aristotle On The Goals and Exactness of EthicsDokument435 SeitenAristotle On The Goals and Exactness of Ethicsmusic2850Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- QJ 03 The Quran HandoutDokument9 SeitenQJ 03 The Quran HandoutamanullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islam Test Review Answer Key 2Dokument6 SeitenIslam Test Review Answer Key 2Abram B. BrosseitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelengkapan Berkas Ijazah SMKN 1 Murung Pudak Kelas Xii Tahun 2021-2022 (Jawaban)Dokument4 SeitenKelengkapan Berkas Ijazah SMKN 1 Murung Pudak Kelas Xii Tahun 2021-2022 (Jawaban)Auriel EelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miracles of ArbaeenDokument3 SeitenMiracles of ArbaeenLuckyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Murtad & HanafiDokument6 SeitenMurtad & HanafiRana MazharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mike Tyson Religion - Google SearchDokument1 SeiteMike Tyson Religion - Google SearchfalqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Santri Yang Tidak Hadir Absen Wajib KedatanganDokument3 SeitenData Santri Yang Tidak Hadir Absen Wajib KedatanganPORSEKA 46Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ideology of PakistanDokument11 SeitenIdeology of PakistanSaima BatoOlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seeking Blessings From TreesDokument2 SeitenSeeking Blessings From TreesSabNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Understanding Arabic Names: The Arabic Naming SystemDokument21 SeitenUnderstanding Arabic Names: The Arabic Naming SystemSteven W ArtNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Asia: Journal of South Asian StudiesDokument35 SeitenSouth Asia: Journal of South Asian Studiesসাদিক মাহবুব ইসলামNoch keine Bewertungen

- G J O Moshay Who Is This Allah PDFDokument92 SeitenG J O Moshay Who Is This Allah PDFIbrahim Zulaikha0% (1)

- Responsibility of Giving EvidenceDokument15 SeitenResponsibility of Giving EvidenceFarah AthirahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muhammad Mohar AliDokument3 SeitenMuhammad Mohar Aliferdousy sarkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- David G. Bromley, J. Gordon Melton - Cults, Religion, and Violence (2002)Dokument271 SeitenDavid G. Bromley, J. Gordon Melton - Cults, Religion, and Violence (2002)aurimia100% (1)

- A Mercy To The WorldsDokument6 SeitenA Mercy To The WorldsAkramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance For The Youth - ML Yunus PatelDokument144 SeitenGuidance For The Youth - ML Yunus PatelKhidr_ibn_SadiqueNoch keine Bewertungen

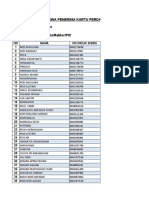

- Daftar Anak Siswa Penerima Kartu Perdana Smartfren Sekolah/Universitas Alamat Nama Kepala Sekola/Rektor/PICDokument20 SeitenDaftar Anak Siswa Penerima Kartu Perdana Smartfren Sekolah/Universitas Alamat Nama Kepala Sekola/Rektor/PICMaha FaathirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Amal ch1Dokument11 SeitenBook of Amal ch1YusufAliBahrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Data Yang Belum Selesai PDM - 11 OKTOBER 2021Dokument195 SeitenData Yang Belum Selesai PDM - 11 OKTOBER 2021Chandra ArisandyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Room ListDokument2 SeitenRoom ListBajri SalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malik Bin DinarDokument17 SeitenMalik Bin DinarRaudhotul MuhibbinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Secret of The Malaysian Success: MahathirDokument17 SeitenThe Secret of The Malaysian Success: MahathircoolkhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- BFDM Volume 37 Issue 37 Pages 356-403Dokument48 SeitenBFDM Volume 37 Issue 37 Pages 356-403draifiasamir83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series No. 84Dokument27 SeitenAsia Research Institute Working Paper Series No. 84Muhammad Nur yusufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biography of Hazrat Mirza Sardar Baig Saheb HyderabadDokument2 SeitenBiography of Hazrat Mirza Sardar Baig Saheb HyderabadMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Markah Uasa RBT Tingkatan 1Dokument15 SeitenMarkah Uasa RBT Tingkatan 1SEKOLAH MENENGAH KEBANGSAAN CENDERAWASIH MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts and Sciences in Abbasid CaliphateDokument3 SeitenArts and Sciences in Abbasid CaliphateAbdul MuqtadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Islamic and Religious Studies 4 2 2Dokument19 SeitenJournal of Islamic and Religious Studies 4 2 2Muhammad DawoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nabuwat Ke Jhoothay Dawedar Aur Qadiani Mazhab by Hazrat Allama Abdul Sattar Hamdani (Maddazillahul Aali)Dokument87 SeitenNabuwat Ke Jhoothay Dawedar Aur Qadiani Mazhab by Hazrat Allama Abdul Sattar Hamdani (Maddazillahul Aali)Gulam-I-Ahmed RazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageVon EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (12)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearVon EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (560)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeVon EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3227)