Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Wanger Ralph The Ralph Wanger Approach Growth at A Reasonable Price

Hochgeladen von

Glenn HackterOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wanger Ralph The Ralph Wanger Approach Growth at A Reasonable Price

Hochgeladen von

Glenn HackterCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

STOCK ANALYSIS WORKSHOP

hgjhgggghghjghgjhgjhgjhgjhgjhgjgjhgjhghggggjhghgjhgjhgjhgjhg gjhgjhfjhgvhgjvgjuhfygcgiujggigugjkhggigiuggjkhgiggjgyghggyhg gjhjhgjhgjhghggjgjhjhjhhkjhkjhkjh kjhkjhbnbmnbjknbnhbnmnbmnbjbjgvjgjhvgvhvvvnnbv kmlklkvnvjbvvjbvvhjvnhgvnhvnmhhnhnhbbbbnngvbnvbhnbnbv nbvvvhjkkkl hgjhgggghghjghgjhgjhgjhgjhgjhgjgjhgjhghggggjhghgjhgjhgjhgjhg gjhgjhfjhgvhgjvgjuhfygcgiujggigugjkhggigiuggjkhgiggjgyghggyhg gjhjhgjhgjhghggjgjhjhjhhkjhkjhkjh kjhkjhbnbmnbjknbnhbnmnbmnbjbjgvjgjhvgvhvvvnnbv kmlklkvnvjbvvjbvvhjvnhgvnhvnmhhnhnhbbbbnngvbnvbhnbnbv nbvvvhjkkkl

The Ralph Wanger Approach: Growth at a Reasonable Price

By Maria Crawford Scott

In the mutual fund manager horse race, Ralph Wanger thinks of himself as a horse of a different coloractually a zebra, to be more accurate, who must stand apart from the herd to find the choice pickings. And Mr. Wanger certainly has stood apart from the crowd, racking up an impressive track record as portfolio manager of the Acorn Fund, a fund that focuses on smallercapitalization stocks. Mr. Wanger has been a consistent promoter of small-stock investing, and has held to his investment philosophy through the best and worst market environments. Although there are numerous small-cap funds today, the Acorn fund is one of the oldest, having been launched by Mr. Wanger in 1970. Mr. Wanger uses the zebra metaphor to argue his case for investing in smaller-capitalization stocks. It is difficult to find the green grass of opportunity among stocks that have been picked over by the heavy competition of other smart, full-time investors. He therefore prefers to stand apart from the herd, a stance most zebras wont take because of fear of becoming lion lunch, and a stance many investors wont take because of the greater risks. His investment approach primarily focuses on finding the opportunities and limiting the risks of investing in smallercapitalization stocks. It is outlined in his new book A Zebra in Lion Country: Ralph Wangers Investment Survival Guide, published by Simon & Schuster (800/223-2336), which is the primary source for this article. The book reflects Mr. Wangers wellknown wit and humor, which have made his Acorn Fund annual report commentaries entertaining; the book itself is highly readable. Why Small-Cap Stocks: The Philosophy Aside from offering less-exploited opportunities, Mr. Wanger points to several other advantages offered by investing in smaller-capitalization stocks, which he defines as companies below $1 billion in market capitalization (share price times number of shares outstanding). First, smaller companies have more room to grow. No company can sustain a high growth rate forever, and eventually a firms size starts to weigh it down. Large companies simply cannot sustain the high growth rates achievable by a fastgrowing company. In addition, Mr. Wanger likes to focus on long-term trends and change. He notes that change creates opportunities for investors who can perceive them and points out that smaller companies can adapt more readily to change. Dumbo could fly because he was a baby elephant. Adult elephants are aerodynamically unsound, he states. There are also more actions that can cause the prices of smallcap companies to rise. Stock prices will rise due to: earnings growth; acquisition by a larger company at an above-market price; stock repurchases by the company; and an increase in the price the market is willing to pay for one dollar of earnings due to increased institutional interest. Typically, though, large-company stock prices rise only for the first reason, while smaller companies will see prices rise for all of those reasons. And, Mr. Wanger finds smaller companies that are in only one or two lines of business to be more easily understandable than large companies that are in many lines of business. Lastly, Mr. Wanger points to numerous academic studies indicating that smaller-cap stocks have provided higher rates of return over long time periods, even after adjusting for the risk. Nonetheless, Mr. Wanger does acknowledge that investing in small-cap stocks is a riskier strategy, particularly since misjudgments are bound to occur. Risk reduction, in Mr. Wangers view, is in the careful selection of specific stocks. To lower the risk of small-cap investing, he suggests investing in companies that are established, with managements that have proven their capabilities over time, that have a sound balance sheet and a strong position in their industry. For that reason, he suggests avoiding stocks that are 3

Maria Crawford Scott is editor of the AAII Journal. May 1997

start-ups, initial public offerings, and turnarounds. He also warns against overpaying for a stock. Lastly, for individual investors, a small-cap portfolio should have at least 12 stocks. Growth Stocks: Trend-Spotting Mr. Wanger seeks growth potential, and he does so first by determining broad areas for potential future growth. Thus, his approach starts with a top-down outlook: He first identifies general themesstrong social, economic, or technological trends that will last longer than one business cycle (at least five years or more). The advantage of focusing on long-term trends, he says, is that most other investors are focused more on shorter-term predictions of two years or less, and it is difficult to outguess the competition, particularly since most investors are privy to the same information. The other advantage of focusing on long-term trends is that you must be a long-term investor, which is particularly important in the smaller-cap area because of high trading costs. What does Mr. Wanger mean by a trend or long-term theme? One example he points to is underdeveloped countries and their development. These countries have been and still are investing in telephone systems, a trend he says has been obvious for many years and which has already benefited many investors in companies such as Mexicos Telefonos de Mexico. He also notes that individuals in developing countries will have more discretionary spendingand will therefore be buying more discretionary items. Other possible theme areas Mr. Wanger points to: Rebuilding of infrastructure in countries worldwide Expansion of communications and transportation networks worldwide Energy exploration of older marginal oil fields by smaller energy companies Outsourcing of services and jobs that require technological and skilled personnel Money management, particularly as public pension systems are privatized Mr. Wanger says that to identify trends, you must develop an observing mind-set, that can draw generalizations from many different particulars. He suggests that trends can best be spotted from reading and ones everyday general experience, including the work environment. And he notes that it is easyand likelythat mistakes will be made, which is why diversification is important. Once a trend has been spotted, Mr. Wanger selects companies that will benefit from these themes. That doesnt mean that the investment is directly in the theme itself, particularly if it is a strong technological trend. In fact, he points out that most companies that are directly involved in trend-setting are the ones that will least benefit from the trend. His best example is firms that are directly involved in technology, which is certainly the most obvious and strongest long-term trend today. Competition among technology firms is strong, and even though there are many geniuses running these companies, they are competing with other geniuses. 4

Instead, Mr. Wanger prefers to invest in companies that will benefit from the technological advancethe downstream users of technology, rather than the technology companies themselves. Examples include the banking industry, which has been transformed through the use of ATM machines, the credit card industry, and the database and data processing industries. Of course, a trend-spotting approach dictates that you must learn to recognize when the trend is played outit no longer offers growth potential. The signs that a trend is ending include: the stocks of firms in the area become too pricey, there are many new issues coming out, and marginal players are starting to enter the field. While trend-spotting is Mr. Wangers primary source for ideas, he also considers a company to be promising if it is not part of a theme but has a near-monopoly in a special market niche that is likely to last more than one business cycle. That, he says, is a theme in itself. Criteria for Purchase The hardest work, in Mr. Wangers view, is the selection process. Selecting a company consists of understanding the company, its products, its industry position, its financials, and its management. Then, you must make a decision as to whether the market price for the stock fairly reflects the companys real value and its prospects. Finding value is an important part of Mr. Wangers approach he believes in growth investing, but only at a reasonable price. However, to find value, you must have a different perspective than others in the marketplace, and you must bring that fresh perspective with you when analyzing a company. Mr. Wangers selection approach emphasizes three areas: growth potential, financial strength, and fundamental value. The growth potential comes from a companys ability to exploit its long-term theme. Thus, Mr. Wanger looks for companies that have a good product, an expanding market, and the ability to efficiently manufacture and market its products. In addition, it should have a special niche, in an area of the market that is not easily entered by competitors. Boring stocks are more likely to fit this description than glamour stocks. Mr. Wanger focuses considerable attention on management, seeking a team that is capable of fully exploiting the companys niche. However, Mr. Wanger notes that this is a qualitative judgment than cannot be made by looking at statistics. Instead, he prefers talking to competitors, suppliers, and management itself (which he acknowledges is difficult for individual investors to do on their own). The signs of good management include: The management team is small and has considerable knowledge of the industry. Its plans for the companys future are reasonable, but not inflexible, and the management is adaptable to changing market conditions. A large share of company stock is owned by the managers. To reduce the risks of investing in smaller-capitalization stocks, Mr. Wanger seeks companies with financial strength. Usually, companies that have survived various economic environments AAII Journal

The Ralph Wanger Approach in Brief

Philosophy and style Investment in companies in which there is a well-grounded expectation concerning the firms growth prospects, and in which the stock can be bought at a reasonable price. The best area for finding stocks that meet these criteria is in the small-capitalization market, in companies with financial strength and market dominance. Universe of stocks Smaller-capitalization companies (less than $1 billion in market capitalization) that are seasoned; no start-ups or initial public offerings. Criteria for initial consideration Identify general themesstrong social, economic, or technological trendsthat will last five years or longer, and select companies that will benefit from these themes. In addition, a company may be promising if it is not part of a theme, but has a near-monopoly in a special market niche. Criteria for purchase Companies must show evidence of: growth potential, financial strength, and fundamental value: Growth potential: Company should have a special niche and should be in an area of the market that is not easily entered by competitors. Company also should have a good management team capable of fully exploiting that niche. Management is judged by talking to competitors, suppliers and management itself. Signs of good management include: The management team is small, with considerable knowledge of the industry; it has reasonable plans for the future but is adaptable to changing markets; and it owns a large share of company stock. Financial strength: Low debt relative to its industry, adequate working capital and conservative accounting practices. For manufacturing or retail businesses, debt should be less than half of companys total capitalization. Balance sheet should be scrutinized for liabilities other than debt (for instance, pension liabilities) and additional hidden assets (for instance, goodwill or intangibles). Inventories and receivables relative to revenues should be examined for stability; rising ratios may indicate problems with sales and warrant further investigation. Companies that have weathered various economic environments tend to have financial strength; turnarounds, start-ups and initial public offerings are more shaky and therefore should be avoided. Fundamental value: Share price should be cheap relative to indications of earnings-growth prospects such as earnings, sales or cash flow; companies with recognized growth potential will have high multiples no matter which measure is used. Be wary of potential problems with each measurefor instance, price-earnings ratios can be misleading due to accounting manipulations of earnings. Operating profitability is best judged by cash flow (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). Also, price should be cheap relative to companys asset value, which takes everything into consideration including long-term and short-term liabilities, as well as intangibles such as brands and patents; book value (assets less depreciation) is not a useful measure. Valuation To help judge value relative to growth potential, a valuation model is used, based on predicted earnings growth rate (not more than two years out), and a predicted price-earnings multiple (adjusted for the expected level of interest rates, since at high interest rate levels, multiples tend to be lower than when interest rates are at low levels). Model provides a price for stock two years hence, and thus an expected rate of return over two years; this is compared to what most analysts are expecting, and the stock is considered cheap if expectations are higher than consensus analyst expectations. Stock monitoring and when to sell Stocks should be held for the long-term, particularly given high trading costs associated with small caps. For adequate diversification, a small-cap portfolio should hold at least 12 stocks. However, an investors total savings portfolio should not be invested only in small-cap stocks, but should consist of large-capitalization stocks and international stocks. When purchasing a stock, the reason for the purchase should be written down. Stock should be sold when the reason for purchasing the stock is no longer valideither it has acheived its expected potential, or it has failed. However, stocks should be continually reevaluated. If the unexpected occurs, for instance, earnings come in lower than expected or other analysts expectations are markedly different, re-evaluate management and its abilities; if original premise remains and the price has dropped, buy more, but if original premise turns out to be incorrect, sell. In general, let profits run.

have some form of financial strength, and for that reason he avoids start-ups, IPOs, and turnarounds. He avoids companies with high levels of debt and where debt is rising, but notes that debt levels must be judged relative to other companies in the industry. For manufacturing or retail businesses, debt should be less than half of companys total capitalization. He also seeks companies with adequate working capital and firms that use conservative accounting practices. Mr. Wanger also suggests examining other balance sheet May 1997

items to make note of other liabilities (for instance, pension liabilities) and other hidden assets (goodwill and other intangibles and undervalued real estate) and to determine if the company is actually generating cash or if reported earnings are primarily due to an accounting function. Inventories and receivables should be examined relative to revenues to note any changes over time; rising ratios are a warning that inventories are building up. The third leg of Mr. Wangers approach is to seek fundamental valuethe share price should be cheap relative to indications 5

of earnings-growth prospects such as earnings, sales or cash flow, or relative to the asset value of the firm. He notes that companies that are recognized for their growth potential by the market will have high multiples no matter which measure is used. He finds advantages and disadvantages with each measure, and notes that investors who use the different measures should be wary of potential problems with eachfor instance, price-earnings ratios can be misleading due to accounting manipulations of earnings. He suggests that operating profitability is best judged by using cash flow (which he defines as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization). And he says that the share price should be cheap relative to a companys asset value, which takes everything into consideration including long-term and short-term liabilities, as well as intangibles such as brands and patents. Mr. Wangers approach examines many different valuation measures, but he also uses a valuation model that helps judge a stocks value relative to its growth potential. The model is based on his own predicted earnings growth rate (not more than two years out) and a predicted price-earnings multiple that is adjusted for the expected level of interest rates (since at high interest rate levels, multiples tend to be lower than when interest rates are at low levels). The valuation model provides a price for stock two years hence, and thus an expected rate of return over two years. This is compared to what most analysts are expecting, and the stock is considered cheap if expectations are higher than consensus analyst expectations. Unfortunately, Mr. Wanger does not reveal his exact formula. [Interestingly, Benjamin Graham used a similar concept in his valuation model, which was discussed in Value Investing: A Look at the Benjamin Graham Approach, May 1996 AAII Journal; the model appears on page 15 of that issue). Monitoring and Selling Stocks Mr. Wanger is a long-term investor, which is particularly important in the smaller-cap area because their illiquidity tends to drive up trading costs. Therefore, stocks should be purchased with the intent to hold for a long time period that is measured in years; if the stock performs as expected, liquidity will be less of a concern when it comes time to sell. Mr. Wanger suggests that when a stock is purchased, the motivating reason for the purchase should be written down. Stocks should then be carefully monitored to make sure that the

reason for purchasing the stock is still valid. That means continuously revising the expected earnings outlook for the firm. If the unexpected occursfor instance, if earnings come in lower than expected or other analysts expectations turn out to be markedly different from your owna re-evaluation of the stock is in order to find out if you have made an error in judgment, or if you have missed important information. If the original premise remains valid and yet the price has dropped, Mr. Wanger views it as a buying opportunity. Stocks should be sold when the reason for purchasing the stock is no longer valideither it has achieved its expected potential, or it has failed. In general, however, Mr. Wanger prefers to let profits run to avoid the mistake of selling too soon. Wanger in Summary While Mr. Wanger makes a strong case for investing in smallercapitalization stocks, he does not feel that these should be an investors only holdings. Instead, he emphasizes the need to diversify holdings among larger-capitalization stocks. Aside from simply ensuring you get adequate performance at all times, he notes you are more likely to stick with a small-cap approach during lean times if other parts of your portfolio are doing well. Mr. Wanger is also a strong proponent of international investing and, in fact, many of the growth opportunities Mr. Wanger seeks are international in nature. However, he points out that investing in foreign markets directly is very difficult for individual investors to accomplish and he suggests the mutual fund route for most investors who want to invest overseas. Lastly, Mr. Wanger states that his own approach is not necessarily the only approach to successful investing. The most important aspect of investing, he says, is to stick with stocks that you really understand, and to stick with a disciplined approach that suits your needs and personality. The accompanying table provides a brief summary of some of the key points in Ralph Wangers approach. Wanger summarizes his own philosophy: Maintain independence of thought and a healthy degree of skepticism, so you wont be drawn into the herd. Dont overpay, no matter how much you like a company. Invest in themes that will give a company a long-term franchise. Invest downstream from technology. Think and invest globally. Find stocks to own, not trade.

AAII Journal

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Practice of Value Investing - , by Li Lu - LONGRIVERDokument10 SeitenThe Practice of Value Investing - , by Li Lu - LONGRIVERNick SposaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Only the Best Will Do: The compelling case for investing in quality growth businessesVon EverandOnly the Best Will Do: The compelling case for investing in quality growth businessesBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (5)

- Moi201102 Super Investors PRINTDokument170 SeitenMoi201102 Super Investors PRINTbrl_oakcliffNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buffet and Returns On CapitalDokument10 SeitenBuffet and Returns On CapitalJason_Rodgers7904Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pat Dorsey Interview On MoatsDokument11 SeitenPat Dorsey Interview On Moatsitsrahulshah100% (1)

- Full Transcript - Mohnish Pabrai's Speech at GoogleDokument16 SeitenFull Transcript - Mohnish Pabrai's Speech at GoogleSagar Agarwal100% (1)

- Common Stocks and Common Sense: The Strategies, Analyses, Decisions, and Emotions of a Particularly Successful Value InvestorVon EverandCommon Stocks and Common Sense: The Strategies, Analyses, Decisions, and Emotions of a Particularly Successful Value InvestorBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Profit Guru Bill NygrenDokument5 SeitenProfit Guru Bill NygrenekramcalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Klarman Yield PigDokument2 SeitenKlarman Yield Pigalexg6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Active Value Investing Process by Vitaliy Katsenelson, CFADokument16 SeitenActive Value Investing Process by Vitaliy Katsenelson, CFAVitaliyKatsenelsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bruce Greenwald Fall 2015Dokument24 SeitenBruce Greenwald Fall 2015ValueWalk100% (1)

- Moats Part OneDokument9 SeitenMoats Part OnerobintanwhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chuck Akre Value Investing Conference Talk - 'An Investor's Odyssey - The Search For Outstanding Investments' PDFDokument10 SeitenChuck Akre Value Investing Conference Talk - 'An Investor's Odyssey - The Search For Outstanding Investments' PDFSunil ParikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes From Mosaic Perspectives On Investing PDFDokument3 SeitenNotes From Mosaic Perspectives On Investing PDFPrakhar Saxena100% (1)

- Value Investor Insight 12 13 Michael Porter InterviewDokument6 SeitenValue Investor Insight 12 13 Michael Porter InterviewTân Trịnh LêNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investing For GrowthDokument8 SeitenInvesting For GrowthAssfaw KebedeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sayings of Chairman Buffett: Editors' Note: While He Rarely GivesDokument3 SeitenSayings of Chairman Buffett: Editors' Note: While He Rarely Givessrinivasan9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anatomy of The Small-Cap AnomalyDokument22 SeitenAnatomy of The Small-Cap AnomalyPKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Small Cap & Special SituationsDokument3 SeitenSmall Cap & Special SituationsAnthony DavianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Value Investor Insight Play Your GameDokument4 SeitenValue Investor Insight Play Your Gamevouzvouz7127100% (1)

- The Wit and Wid Som of Peter LynchDokument4 SeitenThe Wit and Wid Som of Peter LynchTami ColeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes From A Seth Klarman MBA LectureDokument5 SeitenNotes From A Seth Klarman MBA LecturePIYUSH GOPALNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16 Investing Rules From Walter SchlossDokument6 Seiten16 Investing Rules From Walter SchlossRenz LohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Li-Lu - A Value InvestorDokument316 SeitenLi-Lu - A Value Investoraakash87100% (1)

- GI 2004 LectureDokument17 SeitenGI 2004 LectureMarc F. DemshockNoch keine Bewertungen

- Li Lu Sharing His Value Investing InsightsDokument1 SeiteLi Lu Sharing His Value Investing InsightsGurjeev100% (1)

- Bob Robotti - Navigating Deep WatersDokument35 SeitenBob Robotti - Navigating Deep WatersCanadianValue100% (1)

- Chuck Akre Interview ROIICDokument6 SeitenChuck Akre Interview ROIICKen_hoangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tweedy, Browne Company LLC Investment AdvisersDokument20 SeitenTweedy, Browne Company LLC Investment AdviserspothishahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Austrian Economics & InvestingDokument20 SeitenAustrian Economics & InvestingRaj KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Security I Like BestDokument7 SeitenThe Security I Like Bestneo269100% (4)

- 2 Value Investing Lecture by Joel Greenblatt With Strategies of Warren Buffett and Benjamin GrahamDokument5 Seiten2 Value Investing Lecture by Joel Greenblatt With Strategies of Warren Buffett and Benjamin GrahamFrozenTundraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SchlossDokument188 SeitenSchlossEduardo FreitasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proven Strategies of The Worlds Greatest Investors 2012 PDFDokument6 SeitenProven Strategies of The Worlds Greatest Investors 2012 PDFcreat1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Interview With Bill Nygren of Oakmark FundsDokument9 SeitenInterview With Bill Nygren of Oakmark FundsExcessCapitalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Li Lu Top ClassDokument12 SeitenLi Lu Top ClassHo Sim Lang Theophilus100% (1)

- Jan Issue Vii TrialDokument21 SeitenJan Issue Vii TrialDavid TawilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chuck Akre On The Search For Compounding MachinesDokument5 SeitenChuck Akre On The Search For Compounding MachinesHedge Fund ConversationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aquamarine - 2013Dokument84 SeitenAquamarine - 2013sb86Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Identify Wide MoatsDokument18 SeitenHow To Identify Wide MoatsInnerScorecardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohnish Pabrai Chicago Meeting 2009 NotesDokument3 SeitenMohnish Pabrai Chicago Meeting 2009 NotesalexprywesNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Tepper S 2007 Presentation at Carnegie Mellon PDFDokument7 SeitenDavid Tepper S 2007 Presentation at Carnegie Mellon PDFPattyPattersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chuck Akre Transcript VIC 2011Dokument13 SeitenChuck Akre Transcript VIC 2011harishbihaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contrarian Value Bill Miller's Investment Approach Ben HobsonDokument3 SeitenContrarian Value Bill Miller's Investment Approach Ben Hobsonkljlkhy9Noch keine Bewertungen

- Interview With Guy Spier PDFDokument10 SeitenInterview With Guy Spier PDFanandbajaj0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Li Lu WSJ TranscriptDokument2 SeitenLi Lu WSJ TranscriptJames HuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outstanding Investor DigestDokument6 SeitenOutstanding Investor DigestSudhanshuNoch keine Bewertungen

- David WintersDokument8 SeitenDavid WintersRui BárbaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arithmetic of EquitiesDokument5 SeitenArithmetic of Equitiesrwmortell3580Noch keine Bewertungen

- Value Investing (Santos, Greenwald, Eveillard) SP2016Dokument4 SeitenValue Investing (Santos, Greenwald, Eveillard) SP2016darwin12Noch keine Bewertungen

- WSJ - Li Lu ProfileDokument5 SeitenWSJ - Li Lu ProfilezemblaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SRVP OwnerManualDokument33 SeitenSRVP OwnerManualS100% (1)

- Warren Buffett - 50% ReturnDokument4 SeitenWarren Buffett - 50% ReturnKevin SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Years PAt Dorsy PDFDokument32 Seiten10 Years PAt Dorsy PDFGurjeevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dangers of DCF MortierDokument12 SeitenDangers of DCF MortierKitti WongtuntakornNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pabrai Spier Shearn TranscriptDokument27 SeitenPabrai Spier Shearn TranscriptKunalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tesis Sobre David MarksonDokument99 SeitenTesis Sobre David MarksonAlexander Gribenchenko100% (1)

- A Search For Global Value Traps!: Valuex VailDokument30 SeitenA Search For Global Value Traps!: Valuex VailVitaliyKatsenelsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Currency War Has Started: Updated February 4, 2013, 8:44 P.M. ETDokument3 SeitenCurrency War Has Started: Updated February 4, 2013, 8:44 P.M. ETGlenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of Economic Perspectives - Law of One Price in Financial Markets (2003)Dokument12 SeitenJournal of Economic Perspectives - Law of One Price in Financial Markets (2003)casefortrilsNoch keine Bewertungen

- NDF FX FowardsDokument5 SeitenNDF FX FowardsNirav GosarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harmonic Waves The Brief Daily ForecasterDokument1 SeiteHarmonic Waves The Brief Daily ForecasterGlenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

- NDF FX FowardsDokument5 SeitenNDF FX FowardsNirav GosarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viewpoint How Not To Invest1Dokument8 SeitenViewpoint How Not To Invest1Glenn Hackter100% (1)

- EdelweissDokument6 SeitenEdelweissZerohedge100% (1)

- JP Morgan Global Research June 2013Dokument44 SeitenJP Morgan Global Research June 2013Glenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art em Is Capital CurrencyCSCM NOV2011 FinalDokument35 SeitenArt em Is Capital CurrencyCSCM NOV2011 FinalAnonymous i8ErYPNoch keine Bewertungen

- SP500 Update 13AUG11Dokument7 SeitenSP500 Update 13AUG11AndysTechnicalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Freedom of The World MAPDokument1 SeiteEconomic Freedom of The World MAPGlenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

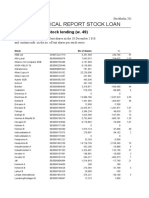

- Statistical Report Stock LoanDokument6 SeitenStatistical Report Stock LoanGlenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Freedom of The World MAPDokument1 SeiteEconomic Freedom of The World MAPGlenn HackterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market Prospect RatiosDokument4 SeitenMarket Prospect RatiosDarlene SarcinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Report of Share KhanDokument117 SeitenProject Report of Share KhanbowsmikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Report On Mutual Funds in IndiaDokument43 SeitenProject Report On Mutual Funds in Indiapednekar_madhuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA FinanceDokument11 SeitenMBA Financeranjithc240% (1)

- Chief Operating Officer CFO in New York City Resume Mark YoungDokument3 SeitenChief Operating Officer CFO in New York City Resume Mark YoungMarkYoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete C7Dokument15 SeitenComplete C7tai nguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- List The Elements of A New-Venture Team?Dokument11 SeitenList The Elements of A New-Venture Team?Amethyst OnlineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Dis Trip Arks ProspectusDokument250 SeitenGlobal Dis Trip Arks ProspectusSandeepan ChaudhuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wealth Builder PDFDokument14 SeitenWealth Builder PDFrajran07Noch keine Bewertungen

- Doubling Up On MomentumDokument48 SeitenDoubling Up On MomentumcastjamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial DerivativesDokument108 SeitenFinancial Derivativesramesh158Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ten Year Treasury YieldsDokument1 SeiteTen Year Treasury YieldsCLORIS4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Classic Securities RegulationDokument58 SeitenClassic Securities RegulationhstansNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1979 Letter To Shareholders - Berkshire HathawayDokument9 Seiten1979 Letter To Shareholders - Berkshire HathawayYashNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Year Performance of Present Gold Trading ContractDokument27 SeitenA Year Performance of Present Gold Trading Contractbalki123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise MahSingvsUEM Financial AnalysisDokument7 SeitenExercise MahSingvsUEM Financial AnalysisAtlantis Ong100% (1)

- How To Attract Investors From SwedenDokument2 SeitenHow To Attract Investors From Swedensinteza_pressNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Ipo in IndiaDokument81 SeitenFinal Ipo in IndiaSumit YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Continued Progress Despite Challenging Economic ConditionsDokument47 SeitenContinued Progress Despite Challenging Economic ConditionsAngie K. EdwardsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Governance in NigeriaDokument20 SeitenCorporate Governance in NigeriaNajar Rim0% (1)

- Prospectus: El Tucuche Fixed Income FundDokument34 SeitenProspectus: El Tucuche Fixed Income FundDillonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wealth Management AssignmentDokument6 SeitenWealth Management AssignmentRakesh MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- H G Infra Engineering LTD: Subscribe For Long Term Price Band: INR 263 - 270Dokument8 SeitenH G Infra Engineering LTD: Subscribe For Long Term Price Band: INR 263 - 270SachinShingoteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hedge Fund Business PlanDokument86 SeitenHedge Fund Business PlanBernardTeunissen50% (2)

- LIC Mutual FundDokument127 SeitenLIC Mutual FundShikha PradhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Private Placement Memorandum Template 07Dokument38 SeitenPrivate Placement Memorandum Template 07charliep8100% (1)

- Acquisition Leveraged Finance (한성원)Dokument18 SeitenAcquisition Leveraged Finance (한성원)Claire Jingyi Li100% (5)

- Introduction of Steel Futures Contracts On The Commodity Futures Market: Effects of Hedging and Speculation On Commodity PricesDokument14 SeitenIntroduction of Steel Futures Contracts On The Commodity Futures Market: Effects of Hedging and Speculation On Commodity PricesSaumil Sharma50% (2)

- MultibaggersDokument33 SeitenMultibaggersgbcoolguyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambodia (Lease Law)Dokument5 SeitenCambodia (Lease Law)jacqNoch keine Bewertungen

- These are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaVon EverandThese are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- Finance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Von EverandFinance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (32)

- Ready, Set, Growth hack:: A beginners guide to growth hacking successVon EverandReady, Set, Growth hack:: A beginners guide to growth hacking successBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (93)

- 2019 Business Credit with no Personal Guarantee: Get over 200K in Business Credit without using your SSNVon Everand2019 Business Credit with no Personal Guarantee: Get over 200K in Business Credit without using your SSNBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (3)

- Summary of The Black Swan: by Nassim Nicholas Taleb | Includes AnalysisVon EverandSummary of The Black Swan: by Nassim Nicholas Taleb | Includes AnalysisBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (6)

- John D. Rockefeller on Making Money: Advice and Words of Wisdom on Building and Sharing WealthVon EverandJohn D. Rockefeller on Making Money: Advice and Words of Wisdom on Building and Sharing WealthBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (20)

- The Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursVon EverandThe Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (8)

- Burn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialVon EverandBurn the Boats: Toss Plan B Overboard and Unleash Your Full PotentialBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (32)

- The Masters of Private Equity and Venture Capital: Management Lessons from the Pioneers of Private InvestingVon EverandThe Masters of Private Equity and Venture Capital: Management Lessons from the Pioneers of Private InvestingBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (17)

- These Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaVon EverandThese Are the Plunderers: How Private Equity Runs—and Wrecks—AmericaBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (8)

- The Caesars Palace Coup: How a Billionaire Brawl Over the Famous Casino Exposed the Power and Greed of Wall StreetVon EverandThe Caesars Palace Coup: How a Billionaire Brawl Over the Famous Casino Exposed the Power and Greed of Wall StreetBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Venture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistVon EverandVenture Deals, 4th Edition: Be Smarter than Your Lawyer and Venture CapitalistBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (73)

- 7 Financial Models for Analysts, Investors and Finance Professionals: Theory and practical tools to help investors analyse businesses using ExcelVon Everand7 Financial Models for Analysts, Investors and Finance Professionals: Theory and practical tools to help investors analyse businesses using ExcelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanVon EverandFinancial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (79)

- Financial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionVon EverandFinancial Risk Management: A Simple IntroductionBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (7)

- Private Equity and Venture Capital in Europe: Markets, Techniques, and DealsVon EverandPrivate Equity and Venture Capital in Europe: Markets, Techniques, and DealsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Applied Corporate Finance. What is a Company worth?Von EverandApplied Corporate Finance. What is a Company worth?Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- Creating Shareholder Value: A Guide For Managers And InvestorsVon EverandCreating Shareholder Value: A Guide For Managers And InvestorsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (8)

- Startup CEO: A Field Guide to Scaling Up Your Business (Techstars)Von EverandStartup CEO: A Field Guide to Scaling Up Your Business (Techstars)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- Joy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerVon EverandJoy of Agility: How to Solve Problems and Succeed SoonerBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Financial Modeling and Valuation: A Practical Guide to Investment Banking and Private EquityVon EverandFinancial Modeling and Valuation: A Practical Guide to Investment Banking and Private EquityBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (4)

- The Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursVon EverandThe Six Secrets of Raising Capital: An Insider's Guide for EntrepreneursBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (34)

- Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinanceVon EverandValue: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate FinanceBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (18)

- Corporate Finance Formulas: A Simple IntroductionVon EverandCorporate Finance Formulas: A Simple IntroductionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (8)