Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Joseph Conrad

Hochgeladen von

liliana_oana3400Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Joseph Conrad

Hochgeladen von

liliana_oana3400Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Jzef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski; 3 December 1857 3 August 1924) was a Polish novelist. Many critics regard him as one of the greatest novelists in the English languagea fact that is remarkable as he did not learn to speak English fluently until he was in his twenties (and always with a Polish accent). Conrad is recognized as a master prose stylist. Some of his works have a strain of romanticism, but more importantly he is recognized as an important forerunner of modernist literature. His narrative style and anti-heroic characters have influenced many writers, including Ernest Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Graham Greene, William S. Burroughs, Joseph Heller, V.S. Naipaul and John Maxwell Coetzee. Writing during the apex of the British Empire, Conrad drew upon his experiences serving in the French and later the British Merchant Navy to create novels and short stories that reflected aspects of a world-wide empire while also plumbing the depths of the human soul. Conrad became a naturalized British citizen in 1886.

Early life

Conrad was born in Berdyczw (now Berdychiv, Ukraine) into a highly patriotic, impoverished Polish noble family bearing the Nacz coat-of-arms. His father Apollo Korzeniowski was a writer of politically themed plays, and a translator of Alfred de Vigny, Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens and Shakespeare from the French and English. He encouraged his son Konrad to read widely in Polish and French. Conrad lived an adventurous life, becoming involved in gunrunning and political conspiracy, which he later fictionalized in his novel The Arrow of Gold, and apparently had a disastrous love affair, which plunged him into despair. His voyage down the coast of Venezuela would provide material for Nostromo. The first mate of Conrad's vessel became the model for Nostromo's hero. In 1878, after a failed suicide attempt in Marseilles by shooting himself in the chest, [2] Conrad took service on his first British ship bound for Constantinople, before its return to Lowestoft, his first landing in Britain. Barely a month after reaching England, Conrad had signed on for the first of six voyages between July and September 1878, from Lowestoft to Newcastle on a coaster misleadingly named Skimmer of the Sea. Crucially for his future career, he 'began to learn English from East Coast chaps, each built to last for ever and coloured like a Christmas card.' In London on 21 September 1881, Conrad set sail for Newcastle as second mate on the small vessel Palestine (13 hands) to pick up a cargo of 557 tons of 'West Hartley' coal bound for Bangkok. From the outset things went wrong. A gale hampered progress (sixteen days to

the Tyne), then the Palestine had to wait a month for a berth - and was finally rammed by a steam vessel. The captain's wife, Mrs Beard, looked after Conrad and sewed his buttons on while he lived on board, moored in the Tyne not far from Percy Main. Palestine sailed from the Tyne at the turn of the year. Then the ship sprang a leak in the Channel and was stuck in Falmouth for a further nine months. After all these misfortunes, Conrad writes: 'Poor old Captain Beard looked like a ghost of a Geordie skipper.' The ship set sail from Falmouth on 17 September 1882 and reached the Sunda Strait in March 1883. Finally, off Java Head, the cargo ignited and fire engulfed the ship. The crew, including Conrad, reached shore safely in open boats. The ship is re-named Judaea in Conrad's famous story 'Youth', which covers all these events. This voyage from the Tyne was Conrad's first fateful contact with the exotic East, the setting for many of his later works. A childhood ambition to visit central Africa was realised in 1889, when Conrad contrived to reach the Congo Free State. He became captain of a Congo steamboat, and the atrocities he witnessed and his experiences there not only informed his most acclaimed and ambiguous work, Heart of Darkness, but served to crystalise his vision of human nature and his beliefs about himself. These were in some measure affected by the emotional trauma and lifelong illness he contracted there. During his stay, he became acquainted with Roger Casement, whose 1904 Congo Report detailed the abuses suffered by the indigenous population. The description of Conrad's protagonist Marlow's journey upriver closely follows Conrad's own, and he appears to have experienced a disturbing insight into the nature of evil. Conrad's experience of loneliness at sea, of corruption and of the pitilessness of nature converged to form a coherent, if bleak, vision of the world. Isolation, self-deception, and the remorseless working out of the consequences of character flaws are threads to be found running through much of his work. Conrad's own sense of loneliness throughout his exile's life would find memorable expression in the 1901 short story, "Amy Foster." In 1891, Conrad stepped down in rank to sail as first mate on the Torrens quite possibly the finest ship ever launched from a Sunderland yard (James Laing's Deptford Yard, 1875). For fifteen years 1875-90, no ship approached her speed for the outward passage to Australia. In her record-breaking run to Adelaide, she covered 16,000 miles in 64 days. Conrad writes of her: 'A ship of brilliant qualities - the way the ship had of letting big seas slip under her did one's heart good to watch. It resembled so much an exhibition of intelligent grace and unerring skill that it could fascinate even the least seamanlike of our passengers.' Conrad made two voyages to Australia aboard her, but in 1894 he had parted from the sea for ever and embarked upon his literary career - having begun writing his first novel Almayer's Folly on board the Torrens.

In March 1896 Conrad married an Englishwoman, Jessie George, and together they moved into a small semi-detached villa in Victoria Road, Stanford le Hope and later to a medieval lath-and-plaster farmhouse, "Ivy Walls," in Billet Lane. He subsequently lived in London and near Canterbury, Kent. The couple had two sons, John and Borys. As the quality of his work declined, he grew increasingly comfortable in his wealth and status. Conrad had a true genius for companionship, and his circle of friends included talented authors such as Stephen Crane and Henry James.

Style

Conrad, an emotional man subject to fits of depression, self-doubt and pessimism, disciplined his romantic temperament with an unsparing moral judgment. As an artist, he famously aspired, in his preface to The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897), "by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel... before all, to make you see. That and no more, and it is everything. If I succeed, you shall find there according to your deserts: encouragement, consolation, fear, charm all you demand and, perhaps, also that glimpse of truth for which you have forgotten to ask." Writing in what to the visual arts was the age of Impressionism, Conrad showed himself in many of his works a prose poet of the highest order: thus, for instance, in the evocative Patna and courtroom scenes of Lord Jim; in the "melancholy-mad elephant" and gunboat scenes of Heart of Darkness; in the doubled protagonists of The Secret Sharer; and in the verbal and conceptual resonances of Nostromo and The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'. The singularity of the universe depicted in Conrad's novels, especially compared to those of near-contemporaries like John Galsworthy, is such as to open him to criticism similar to that later applied to Graham Greene.[10] But where "Greeneland" has been characterised as a recurring and recognisable atmosphere independent of setting, Conrad is at pains to create a sense of place, be it aboard ship or in a remote village. Often he chose to have his characters play out their destinies in isolated or confined circumstances. Conrad's third language remained inescapably under the influence of his first two Polish and French. This makes his English seem unusual. It was perhaps from Polish and French prose styles that he adopted a fondness for triple parallelism, especially in his early works ("all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest, in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men"), as well as for rhetorical abstraction ("It was the stillness of an implacable force brooding over an inscrutable intention"). In Conrad's time, literary critics, while usually commenting favourably on his works, often remarked that his exotic style, complex narration, profound themes and pessimistic ideas put many readers off. Yet as Conrad's ideas were borne out by 20th-century events, in due course

he came to be admired for beliefs that seemed to accord with subsequent times more closely than with his own. Conrad's was, indeed, a starkly lucid view of the human condition a vision similar to that which had been offered in two micro-stories by his ten-years-older Polish compatriot, Bolesaw Prus (whose work Conrad admired): "Mold of the Earth" (1884) and "Shades" (1885). Conrad wrote: Faith is a myth and beliefs shift like mists on the shore; thoughts vanish; words, once pronounced, die; and the memory of yesterday is as shadowy as the hope of to-morrow.... In this world as I have known it we are made to suffer without the shadow of a reason, of a cause or of guilt.... There is no morality, no knowledge and no hope; there is only the consciousness of ourselves which drives us about a world that... is always but a vain and floating appearance.... A moment, a twinkling of an eye and nothing remains but a clot of mud, of cold mud, of dead mud cast into black space, rolling around an extinguished sun. Nothing. Neither thought, nor sound, nor soul. Nothing.

Heart of Darkness

Heart of Darkness is a novella written by Polish-born writer Joseph Conrad (born Jzef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski). Before its 1902 publication, it appeared as a three-part series (1899) in Blackwood's Magazine. It is widely regarded as a significant work of English literature and part of the Western canon. This highly symbolic story is actually a story within a story, or frame narrative. It follows Marlow as he recounts, from dusk through to late night, his adventure into the Congo to a group of men aboard a ship anchored in the Thames Estuary. The story details an incident when Marlow, an Englishman, took a foreign assignment as a ferry-boat captain, employed by a Belgian trading company, on what readers may assume is the Congo River, in the Congo Free State, a private colony of King Leopold II; the country is never specifically named. Marlow is employed to transport ivory downriver; however, his more pressing assignment is to return Kurtz to civilization in a cover up. Kurtz has a reputation throughout the region.

Background

In writing the novella, Conrad drew inspiration from his own experience in the Congo: eight and a half years before writing the book, he had served as the captain of a Congo steamer. However he became ill and returned to Europe. Some of Conrad's experiences in the

Congo, and the story's historic background, including possible models for Kurtz, are recounted in Adam Hochschild's King Leopold's Ghost. It is also alleged that Conrad drew from the adventures of Sir Roger Casement. The story-within-a-story device that Conrad chose for Heart of Darkness one in which an unnamed narrator recounts Marlow's recounting of his journey has many literary precedents. Emily Bront's Wuthering Heights used a similar device, but the best examples of the framed narrative include Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, The Arabian Nights and Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. ]

Motifs and themes

He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath "The horror! The horror!" Africa was known as "The Dark Continent" in the Victorian Era with all the negative attributes of darkness attributed to Africans by the English. One of the possible influences for the Kurtz character was Henry Morton Stanley of "Dr. Livingstone, I presume" fame, as he was a principal explorer of "The Dark Heart of Africa", particularly the Congo. Stanley was infamous in Africa for horrific violence and yet he was honoured by a knighthood. However, an agent Conrad himself encountered when travelling in the Congo, named Georges-Antoine Klein (Klein means 'small' in German, as Kurtz is 'short') could have possibly served as an actual model for the Kurtz that appears in Heart of Darkness. Klein died aboard Conrad's steamer and was interred along the Congo, much like Kurtz in the novel.. Among the people Conrad may have encountered on his journey was a trader called Leon Rom, who was later named chief of the Stanley Falls Station. In 1895 a British traveller reported that Rom had decorated his flower-bed with the skulls of some twenty-one victims of his displeasure, including women and children, resembling the posts of Kurtzs Station.

Themes

The major purpose and theme of Conrad's novella is the exploration of the degradation of human morality through Marlow's symbolic journey towards the "heart of darkness." As Marlow "penetrate[s] deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness," and further and further into the African wilderness, he probes further into the human subconscious and psyche, represented by the jungle. Marlow's experiences in the jungle, and the episodes of barbarism, depict what happens when man crosses the line of civility and gives in to his baser instincts, such as violence. This theme of atavism, or the reversion to more primal or ancestral behaviors and instincts, is featured prominently in the novella. Furthermore, Marlow's symbolic journey can be interpreted with the Sigmund Freud's "psychic apparatus" that involves the id, ego, and super-ego. Most importantly, the id, or the part of the psyche that deals with one's subconscious instincts and basic drives, appears as part of the major theme, where Conrad explores what happens when the id is unleashed.

The reversal of the black and white imagery is also a major theme in the novel. Conrad challenges typical literary associations when he associates "black" with "good" and "white" with "bad" or "evil." The associations of black with good, or at least not with with more moral ambiguity than is typically seen, appear throughout the novel, especially in reference to the African natives and their actions. However, the most prominent example of the white/bad association occurs at the beginning of the novella. When Marlow sets out for Europe to receive his work assignment, he remarks that "I arrived in a city that always makes me think of a whited sepulchre." A sepulchre, or a type of tomb or container for human remains, obviously has bad or morbid connotations. This city, which contains the "Company's offices," can be surmised as a city in Belgium, with which Marlow has notably bad and death-like associations. The synthesis of "whited" and "sepulchre" demonstrates the reversal of black and white connotations that Conrad employes, and uses here to reveal his dislike of the Belgian companies that operated in the Congo where Marlow is sent. To emphasize the theme of darkness within all of mankind, Marlow's narration takes place on a yawl in the Thames tidal estuary. Early in the novella, Marlow recounts how London, the largest, most populous and wealthiest city in the world at the time, was itself a "dark" place in Roman times. The idea that the Romans, at one time, conquered the "savage" Britons parallels Conrad's current tale of the Belgains conquering the "savage" Africans. The theme of darkness lurking beneath the surface of even "civilized" persons appears prominently, and is further explored through the character of Kurtz and through Marlow's passing sense of understanding with the Africans. Themes developed in the novella's later scenes include the navet of Europeans particularly women regarding the various forms of darkness in the Congo; the British traders and Belgian colonialists' abuse of the natives; and man's potential for duplicity. The symbolic levels of the book expand on all of these in terms of a struggle between good and evil (light and darkness), not so much between people as within every major character's soul.

Motifs

In the novel, Conrad uses the river as the vehicle for Marlow to journey further into the "heart of darkness." The descriptions of the river, particularly its depiction as a snake, reveal its symbolic qualities. The river "resembl[es] an immense snake uncoiled" and "it fascinates [Marlow] as a snake would a bird." Not only is Marlow captivated by the river, representing as it does the jungle itself, but its association with a snake gives this "fascination of the abomination" its metaphorical characteristics. The statement that "the snake had charmed me" alludes to both the idea of snake charmer and the snake in the story of Genesis. While typically, a snake charmer would charm the snake, in this case, Marlow is charmed by the snake, a reversal which puts the power in the hands of the river, and thus the jungle wilderness. Furthermore, the allusion to the snake of temptation from the story of Adam and Eve demonstrates how the wilderness itself contains the knowledge of good and evil, and upon

entering that wilderness Marlow will be able to see, or at least explore, the characteristics of humanity as well as good and evil. Throughout the novel Conrad dramatizes a tension in Marlow between the restraint of civilization and the savagery of barbarism. The darkness and amorality which Kurtz exemplifies is argued to be the reality of the human condition, upon which illusory moral structures are draped by civilization. Marlow's confrontation with Kurtz presents him with a 'choice of nightmares' - to commit himself to the savagery of the human condition, or to the lie and veneer of civilized restraint. Though Marlow 'cannot abide a lie' and subsequently cannot perceive civilization as anything but a veneer hiding the savage reality of the human condition, he is also horrified by the darkness of Kurtz he sees in his own heart. After emerging from this experience, his Buddha-like pose aboard the Nellie symbolizes a suspension between this choice of nightmares.

Historical context

The novel is largely autobiographical, based upon Joseph Conrad's six-month journey up the Congo River where he took command of a steamboat in 1890 after the death of its captain. At the time, the river was called the Congo, and the country was the Congo Free State. The area Conrad refers to as the Company Station was an actual location called Matadi, a location two-hundred miles up river from the mouth of the Congo. The Central Station was a location called Kinshasa, and both these locations marked a stretch of river impassable by steamboat, upon which Marlow takes a "two-hundred mile tramp." The Company was in reality the Anglo-Belgium India-Rubber Company formed by King Leopold II of Belgium charged with running the country of the Congo Free State in 1885. The Congo Free State was voted into existence by the Congress of Berlin, which Conrad refers to sarcastically in his novella as "the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs." Leopold II declared the Congo Free State his personal property in 1892, legally permitting the Belgians to take what rubber they wished from the area without having to trade with the African natives. This caused a rise in atrocities perpetrated by the Belgian traders. The Congo Free State was taken out of the personal property of the king and made a regular colony of Belgium, called Belgian Congo, in 1908, after the extent of atrocities committed there became generally known in the West, partially through Conrad's novel. Heart of Darkness is also criticized for its characterization of women. In the novel, Marlow says that "It's queer how out of touch with truth women are." Marlow also suggests that women have to be sheltered from the truth in order to keep their own fantasy world from "shattering before the first sunset."

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- How To Play The GameDokument1 SeiteHow To Play The Gameliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Welcome Wall Decals, International Welcome Words, Welcome Decor, Office Reception Decor, School Welcome, Global Greetings, Welcome SignDokument2 SeitenWelcome Wall Decals, International Welcome Words, Welcome Decor, Office Reception Decor, School Welcome, Global Greetings, Welcome Signliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fear AnxietyDokument1 SeiteFear Anxietyliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Expressing RegretsDokument1 SeiteExpressing Regretsliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Expressing RegretsDokument1 SeiteExpressing Regretsliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Picasso Guernica Its StoryDokument19 SeitenPicasso Guernica Its Storyliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Entitlement Mentality and Its CharacteristicsDokument2 SeitenAn Entitlement Mentality and Its Characteristicsliliana_oana3400100% (1)

- Cooperative-Learning: Essential 5Dokument5 SeitenCooperative-Learning: Essential 5liliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plan de Lectie Glorious FoodDokument4 SeitenPlan de Lectie Glorious FoodAndreeaStanciuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Informal Letter Laura ChiticeanuDokument1 SeiteInformal Letter Laura Chiticeanuliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adversity and Dealing WithDokument140 SeitenAdversity and Dealing Withliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Celtic New Year Festival SamhainDokument1 SeiteCeltic New Year Festival SamhainDaniela GreereNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kinds of Sentences in EnglishDokument1 SeiteKinds of Sentences in Englishliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Expressing RegretsDokument1 SeiteExpressing Regretsliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan AssessmentDokument8 SeitenLesson Plan Assessmentliliana_oana34000% (1)

- Vocab Ular 1Dokument3 SeitenVocab Ular 1liliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Food TipsDokument2 SeitenFood TipsOvidiu VintilăNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 Test Snapshot Units 34 ViithDokument2 Seiten0 Test Snapshot Units 34 ViithvclondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deck The Hall1Dokument1 SeiteDeck The Hall1liliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- White Christmas LyricsDokument1 SeiteWhite Christmas LyricsMiguel Angel Gomez AguadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expressing RegretsDokument1 SeiteExpressing Regretsliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Test EnglezaDokument4 SeitenTest EnglezaAlexandra DincaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deck The Hall1Dokument1 SeiteDeck The Hall1liliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rudolph The Red Nosed Reindee1Dokument2 SeitenRudolph The Red Nosed Reindee1liliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Santa Claus Is Coming To TownDokument1 SeiteSanta Claus Is Coming To TownClaudia SamfiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Superman Exist For RealDokument5 SeitenDoes Superman Exist For Realliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Versuri DisneyDokument1 SeiteVersuri Disneyliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Expressing RegretsDokument1 SeiteExpressing Regretsliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- To Be Going ToDokument1 SeiteTo Be Going Toliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- Forum Idei GradeDokument2 SeitenForum Idei Gradeliliana_oana3400Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Today I Will Tell You About The Chapulin ColoradoDokument1 SeiteToday I Will Tell You About The Chapulin ColoradoCracker YerbesNoch keine Bewertungen

- GatsbyDokument28 SeitenGatsbyVictor V.Noch keine Bewertungen

- English Worksheet 1 Class X1Dokument3 SeitenEnglish Worksheet 1 Class X1Praganya GargNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fifteenth Character by Rosemary BorderDokument9 SeitenThe Fifteenth Character by Rosemary BorderElizabeth Alavez GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sports Killerstrated Issue 2Dokument22 SeitenSports Killerstrated Issue 2Sébastien CosseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Readers: Intermediate 2Dokument6 SeitenOur Readers: Intermediate 2klaraseheultNoch keine Bewertungen

- LP A Day in The CountryDokument4 SeitenLP A Day in The CountryLea Marie CabandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quarter 3-Module 1 - English 6Dokument15 SeitenQuarter 3-Module 1 - English 6Grace Angelie Dale ManulatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conversation QuestionsDokument2 SeitenConversation QuestionsFernanda Pantaleão100% (1)

- Dream Jumper, Book 1: Nightmare Escape (Excerpt)Dokument22 SeitenDream Jumper, Book 1: Nightmare Escape (Excerpt)I Read YA67% (15)

- CNFQ 4 Week 1Dokument3 SeitenCNFQ 4 Week 1Jasper Ycong100% (2)

- Book Review " THE GREAT GATSBY "Dokument5 SeitenBook Review " THE GREAT GATSBY "sayemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Narrative Hooks,.Ppt AGOSDokument12 SeitenNarrative Hooks,.Ppt AGOSAtif MohammadNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Curious Incident of The Dog in The Night Time Discussion QuestionsDokument2 SeitenThe Curious Incident of The Dog in The Night Time Discussion QuestionsElizabeth ZhouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behind The Dune Walk ThroughDokument3 SeitenBehind The Dune Walk Through3amoora42% (26)

- Gish in 3.5 Giant in The Playground ForumsDokument33 SeitenGish in 3.5 Giant in The Playground ForumsMark NabongNoch keine Bewertungen

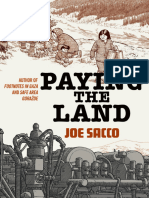

- Paying The Land by Joe SaccoDokument548 SeitenPaying The Land by Joe Saccozsjzi-opossum.difficultNoch keine Bewertungen

- Doris Lessing On Feminism, Communism and 'Space Fiction': Archive - TodayDokument10 SeitenDoris Lessing On Feminism, Communism and 'Space Fiction': Archive - TodayRobertt MosheNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Face of ItDokument1 SeiteOn The Face of Itdheeraj sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bestselling BooksDokument41 SeitenBestselling Bookslisda-ikhwantini-6360Noch keine Bewertungen

- English 1 Student's BookDokument20 SeitenEnglish 1 Student's BookHursepuny Venesia100% (1)

- The Contemporary PeriodDokument25 SeitenThe Contemporary PeriodAlvin GacerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Approaching The Hunger Games Trilogy A Literary and Cultural Analysis (Tom Henthorne)Dokument244 SeitenApproaching The Hunger Games Trilogy A Literary and Cultural Analysis (Tom Henthorne)Adina OstacioaieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hamlet Shakespeare DissertationDokument5 SeitenHamlet Shakespeare DissertationWriteMyPaperCoAtlanta100% (1)

- Reflection 2 Fantasy Sci FiDokument3 SeitenReflection 2 Fantasy Sci Fiapi-531843492Noch keine Bewertungen

- Infinitive, Gerund and Participle Forms ExplainedDokument4 SeitenInfinitive, Gerund and Participle Forms ExplainedSofia So67% (3)

- 500 Greatest Comic BooksDokument7 Seiten500 Greatest Comic BookstwoshoesnotfellowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- TsukumoDokument8 SeitenTsukumoaventurii3453Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poe's Psychological HorrorDokument3 SeitenPoe's Psychological HorrorVanessa RidolfiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kick-Ass 2 Issue #1 - Read Kick-Ass 2 Issue #1 Comic Online in High QualityDokument1 SeiteKick-Ass 2 Issue #1 - Read Kick-Ass 2 Issue #1 Comic Online in High QualitySckakuraNoch keine Bewertungen