Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Ethics of Stadium Funding: Naming Rights Schemes and The Public Good

Hochgeladen von

elmauterOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Ethics of Stadium Funding: Naming Rights Schemes and The Public Good

Hochgeladen von

elmauterCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Running head: STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

The Ethics of Stadium Funding: Naming Rights Schemes and the Public Good Erica L. Mauter St. Catherine University ORLD 7100, Professional and Organizational Ethics July 26, 2013

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD The day outdoor Major League Baseball returned to Minnesota

The Minnesota state legislature passed legislation in 2006 authorizing the construction of a new stadium for the Minnesota Twins Major League Baseball team. The Twins began play at Target Field in 2010. The public contributes financing for the stadium via a Hennepin County sales tax. The Twins sold ballpark naming rights to the Target Corporation, subsidizing the teams contributions towards both construction and ongoing operations. The Twins also sold an environmental sponsorship to Pentair, subsidizing some infrastructure costs while helping the team to achieve LEED certification. The intangible benefit of a sports team to its host community is often described in terms of civic identity, creating a non-economic rationale for public funding. Selling naming rights reduces the cost of stadium construction to the teams owner. Public discussion over stadium construction and funding pits the intangible civic benefit to the community against the economic benefit to the team attained at the expense of the community. Michael Sandel, in his book What Money Cant Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets, posits that selling naming rights has an inherent corruptive effect by applying market principles to something that previously was valued in terms other than its utility (2012). However, if a stadium sponsorship is sold to an entity that represents or provides a public benefit, does that balance the corruptive effect of selling the sponsorship in the first place? I will examine this valuation in the case of the Minnesota Twins and the different sponsorships sold to Target and to Pentair. The benefits of sports teams and the economics of stadiums Tangible benefits The argument in favor of a naming rights arrangement is one of economic efficiency. As Sandel explains throughout his book, creating a market and hence letting market forces dictate

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

the allocation of resources is, per an economist, the most efficient way to allocate those resources (2012). In a free market scenario, each participant gets the greatest possible value out of a transaction. When naming rights are for sale, both the property owner and the advertiser freely participate in that market, and market forces ensure that each party is properly compensated. Jordan Rappaport and Chad Wilkerson from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City attempt to define the benefits of hosting a major league sports franchise with economic data (2001). They estimate revenue from job creation and taxes and compare that to the cost of stadium construction, concluding that the cost to the public outstrips the benefit. Marc Edelman cites a number of studies, finding no positive correlation between facility construction and economic development and asserts that the social benefits of building public stadiums skew in favor of the wealthy, whereas the costs skew in favor of the middle- and lower-class. In other words, government spending on sports facilities fails to follow the benefits principle of taxation the principle that each taxpayers contribution to provide for a public service should remain in proportion to the benefits received from that service. Edelman also notes the regressive nature of sales taxes and lotteries, the most common sources of public funds for stadium construction, and that the primary benefit of the subsidygetting to attend gamesis too expensive and thus excludes some members of the community (2008). In the specific case of Target Field, the legislation authorizing the construction of the stadium contained requirements specifically designed to benefit the public. One such requirement was LEED certification, a standardized rating of sustainable building construction and operation. Another requirement was to direct a portion of the new county sales tax to Hennepin Youth Sports and to Hennepin County Libraries. Intangible benefits

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD Rappaport and Wilkerson also attempt to quantify the quality of life benefits derived from the presence of a major league sports team, concluding that such benefits can potentially justify the public outlay (2001). It should be noted that this is, as Sandel warns against, attempting to use market principles to render a nonjudgmental valuation for something that is typically valued by moral principles (2012). Additionally, this analysis does not take into account the decision-making processes surrounding the public outlay and the power (or lack thereof) of non-elite community members to influence it. Rick Eckstein and Kevin Delaney consider the alleged noneconomic benefits of community self-esteem and community collective conscience to be socially constructed by the powerful to achieve the goal of stadium support despite community resistance to the weak economic case. They find that these arguments have more resonance in some places than others, and prey upon peoples fears that their city will some how become a lesser place without this major league sports team (2002). Its the Cold Omaha argument, which has apparently been

used not only in the Twin Cities, but also in Denver and in St. Louis. Similarly, Phoenix is afraid of becoming Tucson, and Cincinnati would hate to become Dayton. This construction deliberately manipulates what Eckstein and Delaney call internal selfesteemIs this city first-rate?and external self-esteemCan this city compete for talent against other cities? Eckstein and Delaney describe the community collective conscience construction as a narrative positioning sports enjoyment as social glue that used to be provided by religion and/or the more frequent personal interactions typical of life in times past (2002). Eckstein and Delaney use the Metrodome as an example of economic development not following behind new stadium construction. They also suggest that these narratives are used to purposely

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD obfuscate inequality issues and note that such issues typically persist even in the presence of a successful team that enjoys good attendance (2002). Naming rights

Target Field is funded by both the Twins and by public dollars. Per the amended ballpark budget, additional infrastructure costs were borne by the Minnesota Department of Transportation, the Minnesota Ballpark Authority, and Target Corporation. (Minnesota Ballpark Authority, n.d.) Targets contribution to construction is separate from the cost of its naming rights deal, in which Target pays the Twins to have the ballpark bear the Target name. Selling naming rights offsets the cost to the team, but not the cost to the public. Sandel has two arguments against selling naming rights. Once is the concept of coercion or fairness. In a coercion scenario, one party to the transaction is not truly free to participate in the transaction. The conditions of the transaction are unfair, often because one party is under economic distress, which influences the choice to participate in the transaction or the agreedupon terms of the transaction (2012). Sandels second argument against selling naming rights is the concept of corruption or degradation. In a corruption scenario, creating a market for an item that was previously valued solely on moral terms fundamentally changes the meaning of that item and hence inherently devalues that item (2012). Josh Boyd describes the corruptive effect of naming rights as destruction of the commemorative function of place names, which alters for the worse the communitys narrative of its team. Replacing commemorative names with corporate ones signals that the sporting event is actually a business transaction and re-positions fans as customers (2000). Additionally, naming is an exercise of political power, is an opaque process, and usually benefits wealthy white men,

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD thus further bestowing them with public goodwill (Bartow, 2007) while excluding large segments of the community. Environmental sponsorships If the availability of naming rights for sale is inherently degrading to the object being named, can a name that represents or provides a public good make up for that degradation?

Cathy Hartman and Edwin Stafford talked about the concept of Market-Based Environmentalism in the late 1990s. They described the objective as creating market incentives that make ecology strategically attractive to businesses, stressing the importance of integrating waste reduction and resource maximization goals with social needs (1997). I will explore this more, using as an example the company GreenMark, "the leading environmental marketing and green sponsorship agency in sports and live entertainment (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010) and an environmental sponsorship GreenMark brokered between the Twins and Pentair, Inc. Case study: The Twins, Pentair, and GreenMark In addition to selling the naming rights of the ballpark to Target, the Twins also sold an environmental sponsorship to Pentair. The GreenMark Company facilitated this sponsorship. This sponsorship had the following benefits: It helped achieve the required LEED certification, which in turn ensures more environmentally friendly stadium operations; it directly offset the cost of LEED certification for the Twins; and it benefits the Minneapolis municipal water system and its other users due to significantly reduced demand on the water system brought about by Pentairs construction contributions. GreenMark purports to solve environmental problems in building projects while repairing the public image of the entity undertaking the project (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010). GreenMark states that green facility design, products, and practices provide both tangible and

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

intangible benefits. GreenMark refers to a sports and entertainment venue as a community icon and states that building and operating such a venue with environmental commitment provides a platform to tell a sponsors sustainability story (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010). Per this description, one could categorize the green design, products, and practices as a tangible benefit for both the public and the ownership, and the platform for storytelling as an intangible benefit for the ownership and the sponsor. GreenMark further describes intangible benefits for the sponsor as category exclusivity, earned news value, increased brand prestige, heartfelt brand connections and community connections, and tangible benefits for the sponsor as suites, tickets, hospitality, player appearances and media buys (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010). Indeed, GreenMarks founder, Mark Andrew, said, I was amazed to learn that many sports venues the world over had significant sustainable elements. However, none had commercially exploited this stewardship (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010). In an interview with the Star Tribune, Andrew again speaks to both the commercial and community aspects of a sports venue. Sports buildings are iconic structures, gigantic billboards that can be testimony to commercialization. And they can be community assets, setting an example to educate the public about the economics of green buildings and environmental stewardship (St. Anthony, 2010). Andrew also acknowledges that, "At the end of the day, the industry will move only if there's money to be made. You can actually make a profit by doing right by the environment" (The Associated Press, 2010). To determine what goods and services are exchanged in a GreenMark environmental sponsorship deal, we can examine GreenMarks case study of the partnership between the Twins and Pentair. (GreenMark Enterprises LLC, 2010).

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

Participant Pentair

Contributes

tap water filtration products in suites, admin offices, training rooms custom built rain water recycling system FOR FREE sponsorship fee information about Pentairs products business services Target Field concourse display space

Receives

title of Official Sustainable Water Provider Target Field concourse display 100 million media impressions

GreenMark Minnesota Twins

sponsorship fee 100 million media impressions sponsorship fee credit toward LEED certification massively reduced municipal water bill tap water filtration products filtered water for staff, athletes, suiteholders free, custom-built rain water recycling system 100 million media impressions reduced demand on municipal water system information about Pentairs products signal from Twins and Pentair that sustainability is important

Public

100 million media impressions continued support for the Twins and Pentair

From this analysis, its clear how tangible and intangible benefits are exchanged between the property owner (the Twins), the sponsor (Pentair), the facilitator of the sponsorship (GreenMark), and the public (people who live in Minneapolis, who see Minneapolis media, and/or who go to Twins games). Lets assume that these benefits were exchanged at the maximum possible value according to the market at the time. In this environmental sponsorship scheme, market efficiency was achieved according to utilitarian principles. Does Sandels coercion argument hold up under this environmental sponsorship scheme? Each of those four entities is free to enter into transactions in which they exchange money, goods, services, time, or attention. Its possible the Twins ownership group needed the sponsorship money from Pentair to finance the overall Target Field project. Also, the Twins may not have been able to achieve LEED certification without this project. If these two things are true, you could argue that the conditions of the transaction were unfair to the Twins organization.

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD Given the fact that the Twins and state and local government had to agree upon financing and many other facets of this project, it is hard to tease out which entity, if any, may have been coerced. However, if there was commitment and agreement that the project would go forward regardless, and government has committed public funds to help to finance the project, it is a benefit to the both the government (and by proxy, the general public) and to the Twins ownership to achieve market efficiency and lower the overall cost of the project. Some citizens are constrained by the cost of attending a Twins game. Some citizens may be exposed to embedded Pentair advertising against their will, but their choice to attend a gameif they can afford itis voluntary. The coercion argument is weak. Does Sandels corruption argument hold up under this environmental sponsorship scheme? Sandels point is that market efficiency is not a virtue in and of itself. An item covered with ads still works as built, but an item covered with ads has new meaning. Sandel concedes that people may disagree about the old meaning and the new meaning, but people can agree that the meaning has changed. Agreeing that this change has occurred is, to Sandel, the proofthe definitionof corruption (2012). However, if people agree that the new meaning is more positivethat a demonstrably sustainably built Target Field is a public benefitthen both tangible and intangible value have been added. Sandels corruption argument is set up such that the selling of naming rights (or environmental sponsorships) is inherently degrading, but that depends on we as a community agreeing that our sense of community is reduced or altered by showing up to a baseball game where were treated to a commercial for Pentair while were standing in line for a hot dog. Our collective opinion on this may change as the sustainability movement evolves.

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD There is evidence that sustainable practices are highly valued by both consumers and institutions. Albertville and the Savoie region of France sustained significant environmental damage due to hosting the 1992 Olympic Winter Games. The Norwegians championed and

10

implemented a sustainable approach to the 1994 Lillehammer games. Following Norways lead, the International Olympic Committee adopted environmental policy as the third dimension of the Olympic movement, alongside sport and culture, in time for the 1994 Winter Games (Cantelon & Letters, 2000). A study of the effectiveness of environmental advertising in the hotel industry showed that substantive claims around environmental practices elicited positive responses from consumers (Hu, 2012). This finding suggests that Pentairs concourse display describing its rainwater recycling project and filtration systems is critical to conveying such a message to consumers about Target Field. Ethics of funding sports stadiums Further elaborating on the corruptive effect of advertising, Sandel distinguishes between ads on stadium scoreboards and ads embedded in the call of the game (2012). With that distinction, its fair to characterize Pentairs Target Field concourse display as more like a billboard than an unexpected intrusion into the nature of the game itself. That the stadium itself is named for a sponsor creates an expectation that there will be further advertising inside. And while the commercialization of baseball may not be the highest moral ideal, it has become the social norm. Sandel positions municipal marketingthe selling of naming rights on public propertyas somewhat more objectionable because it threatens to bring commercialism into the heart of civic life (2012), which leads one to circle back and question two things: the impact of sponsorships inside a stadium where the intangible benefit of the sporting event within is supposedly the bolstering of civic life, and just how many public dollars need to go into a

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD

11

stadium for it to be considered public property. All that said, while Sandel has arguments against these practices, he does not go so far as to call them unethical. Daniel Mason and Trevor Slack use stakeholder theory to identify the host community as a primary stakeholder and hence frame team owner behavior in terms of business ethics. If the relationship between the team and the host community is reciprocal, then the moral thing to do is to consider the community when making business decisions regarding the team. One dimension Mason and Slack describe is the team in the small market, which exploits government support instead of making business decisions to mutually benefit all stakeholders, and in doing so further burdens its primary stakeholder. This demonstrates a significant power imbalance between a team and the community. Mason and Slack also describe how relocation decisions by team owners undermine the health of the league overall, which demonstrates how owners put their own profit interest above the interests of both the league and the community (1997). This behavior may make sense according to business and legal principles, but per stakeholder theory, it is unethical. The opposite approach is communitarian in nature; theres a shared vision of common good and of core values, cooperation is fostered, the sense of community is continuously affirmed (perhaps through Boyds commemorative naming of places), responsive and accountable government maintains the community, and most importantly, leadership comes from every segment of society (Johnson, 2012). Mason, this time writing with Ernest Buist, analyzed public discourse around one stadium referendum. They found that the voices most heard in the media were those of political and business elites and the media itself, with little or no direct representation of private citizens (2013). Mark Andrew articulated exactly Boyds description of the signaling effect of sponsored

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD naming, that sports are a business and fans are consumers. This indicates that, from the sponsorship brokers point of view, the primary stakeholder is not the sports fan.

12

If a stadium is financed by both team ownership and public dollars, then it could certainly be considered a public-private partnership. Breitenstein and Roberts, writing on public-private partnerships, describe corporations as socially constructed entities, with socially constructed property rights, playing a socially constructed game. As such, they are not merely entitled to a right to profit but may also reasonably bear other obligations as co-constructed with their public partners (2002). This is where a community benefits agreement has power. No such formal agreement is in place, that I could find, for Target Field. This does not preclude the Twins from acting in the interests of the community over their own profit, but it does not require it, either. While the end result of the construction of Target Field is a facility in which Minnesotans take pride and enjoy for its tangible and intangible benefits, the fact is the background conditions that led to the construction and the public financing of the stadium still exist. The end does not justify the means. Team ownership still holds leverage over politicians and business leaders and over the hearts and minds of the community. Politicians and business leaders are still the primary drivers of public narrative about stadium funding. The business and legal environment still encourages team owners to maximize profit at the expense of the league and the community. The economic benefits of public stadium funding still skew in favor of the wealthy and the costs still skew in favor of the lower- and middle-class. Societal inequalities remain unchanged by the existence of a new stadium. Consumers value environmental sustainability, and the environmental sponsorship orchestrated by GreenMark has provided a community benefit. But the corruptive nature of naming rights and the overall atmosphere of commercialization has not been disrupted.

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD References Bartow, A. (2007). Trademarks of Privilege: Naming Rights and the Physical Public Domain. University of California-Davis Law Review, 40(919).

13

Boyd, J. (2000). Selling home: Corporate stadium names and the destruction of commemoration. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 28(4), 330-346. Cantelon, H., & Letters, M. (2000). The making of the IOC environmental policy as the third dimension of the Olympic movement. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 35(3), 294-308. Cook, M. (2010, April 8). Target Field gets LEED certification: Criteria include energy, water efficiency; emissions reductions. MLB.com. Retrieved from: http://minnesota.twins.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20100408&content_id=9142070& vkey=news_min&c_id=min Eckstein, R., & Delaney, K. (2002). New sports stadiums, community self-esteem, and community collective conscience. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 26(3), 235-247. Edelman, M. (2008). Sports and the city: How to curb professional sports teams' demands for free public stadiums. Rutgers Journal of Law and Urban Policy, 6(1). GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). About GreenMark. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/about.html GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). From Undrinkable to Unthinkable: Pentair and Twins Announce Sustainable Water Partnership. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/pdf/GreenMark%20Case%20Study%20-%20Pentair1.pdf

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). GreenMarkSports - Our Founder. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/about/greenmark-founder.html GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). GreenMarkSports - Our Story. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/about/greenmark-story.html

14

GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). Home. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/ GreenMark Enterprises LLC. (2010). Our Sponsorships. Retrieved from: http://www.greenmarksports.com/work.html Hartman, C. L., & Stafford, E. R. (1997). Green alliances: Building new business with environmental groups. Long Range Planning, 30(2), 184-149. Hsin-Hui, H. (2012). The effectiveness of environmental advertising in the hotel industry. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 53(2), 154-164. Johnson, C.E. (2012). Meeting the Ethical Challenges of Leadership: Casting Light or Shadow. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Mason, D. S., & Buist, E. A. (2013). "Domed" to fail? diverging stakeholder interests in a stadium referendum. Journal of Urban History, XX(X), 1-17. Mason, D.S., & Slack, T. (1997). Appropriate Opportunism or Bad Business Practice? Stakeholder Theory, Ethics, and the Franchise Relocation Issue. Marquette Sports Law Review, 7(399). Minnesota Ballpark Authority. Retrieved from: http://www.ballparkauthority.com/Budget.html Nowak, J. (2011, December 13). Target Field earns LEED Silver Certification. MLB.com. Retrieved from: http://minnesota.twins.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20111213&content_id=26154796 &vkey=news_min&c_id=min

STADIUM FUNDING, SPONSORSHIP, AND THE PUBLIC GOOD Rappaport, J., & Wilkerson, C. (2001). What are the benefits of hosting a major league sports franchise? Economic Review, 86(1), 55. Roberts, M. J., Breitenstein, A., & Roberts, C. S. (2002). The ethics of public-private partnerships. Public-Private Partnerships for Public Health, 67-86. Sandel, M.J. (2012). What Money Cant Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

15

St. Anthony, N. (2010, June 22). Mark Andrews environmental firm GreenMark takes the field. Star Tribune. Retrieved from: http://www.startribune.com/business/96852084.html?page=2&c=y

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Intangible Benefits of Sports TeamsDokument26 SeitenThe Intangible Benefits of Sports TeamsIvanakbarPurwamaskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban Power Structures and Publicly Financed Stadiums.Dokument24 SeitenUrban Power Structures and Publicly Financed Stadiums.WestNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Are The Financial Issues Present?Dokument2 SeitenWhat Are The Financial Issues Present?Davis Sagini ArtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economics ReportDokument8 SeitenEconomics Reportapi-664553209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Article - SonicsGateDokument53 SeitenJournal Article - SonicsGateSJBUCFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Garber Revised JuneDokument31 SeitenGarber Revised Junewzheng40Noch keine Bewertungen

- Municipal Bonds: Batter Up: Public Sector Support For Professional Sports FacilitiesDokument35 SeitenMunicipal Bonds: Batter Up: Public Sector Support For Professional Sports FacilitiesMichael OzanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mpeters Final Paper 8-27-14Dokument18 SeitenMpeters Final Paper 8-27-14api-197178125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stadiums ReportDokument26 SeitenStadiums ReportRicardo S AzevedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Public Funds Should Be Used For Building StadiumsDokument12 SeitenWhy Public Funds Should Be Used For Building StadiumsMohd GulzarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CMGT 500 - NFL SponsorshipsDokument27 SeitenCMGT 500 - NFL Sponsorshipsapi-548582952100% (1)

- Commercialization of SportsDokument24 SeitenCommercialization of Sportsmy workNoch keine Bewertungen

- NFL and Stadium FundingDokument10 SeitenNFL and Stadium FundingLUC1F3RNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bidding For The Olympics: Fool's Gold?Dokument40 SeitenBidding For The Olympics: Fool's Gold?prongmxNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Raising of Corporate Sponsorship: A Behavioral Study: Linda BrennanDokument16 SeitenThe Raising of Corporate Sponsorship: A Behavioral Study: Linda BrennanReel LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gambling Sponsorship in Sport Final Edited FileDokument10 SeitenGambling Sponsorship in Sport Final Edited FileRobbe Van EmelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fan Relationship Management Is Key in Professional SportsDokument16 SeitenFan Relationship Management Is Key in Professional SportsNadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dropping The Ball - A Political and Economic Analysis of Public SuDokument69 SeitenDropping The Ball - A Political and Economic Analysis of Public SuWilliam Neilson Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Protecting Detroit's Taxpayers: Stadium Finance Reform Through An Excise TaxDokument3 SeitenProtecting Detroit's Taxpayers: Stadium Finance Reform Through An Excise TaxRoosevelt Campus NetworkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answer To Question No.1Dokument9 SeitenAnswer To Question No.1DJ FahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: Financial Trends of Collegiate Sports 1Dokument9 SeitenRunning Head: Financial Trends of Collegiate Sports 1Vidzone CyberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Identifying The Real Costs and Benefits of Sports FacilitiesDokument3 SeitenIdentifying The Real Costs and Benefits of Sports FacilitiesMühâmmâd Hâššâñ ÂńśãrîNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orlando and Conspicuous Growth - Bates-2Dokument13 SeitenOrlando and Conspicuous Growth - Bates-2Samuel BatesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antitrust Laws' Role in Shaping Pro Sports FinancesDokument7 SeitenAntitrust Laws' Role in Shaping Pro Sports Financesmarinel oroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persuasive Essay Sport Stadium Paper 2Dokument5 SeitenPersuasive Essay Sport Stadium Paper 2Knkighthaw0% (1)

- Advertising Exposure and Portfolio Choice: Estimates Based On Sports SponsorshipsDokument65 SeitenAdvertising Exposure and Portfolio Choice: Estimates Based On Sports SponsorshipspjNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1962 - Esports Media Rights Whitepaper 0921Dokument17 Seiten1962 - Esports Media Rights Whitepaper 0921JoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay 2Dokument19 SeitenEssay 2Hany A AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Sector of Sport (P1)Dokument25 SeitenPublic Sector of Sport (P1)tavsdownerNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSRN Id3640706Dokument36 SeitenSSRN Id3640706L Prakash JenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soccer Sponsor: Fan or Businessman?: Iuliia Naidenova, Petr Parshakov, Alexey ChmykhovDokument13 SeitenSoccer Sponsor: Fan or Businessman?: Iuliia Naidenova, Petr Parshakov, Alexey ChmykhovEstherTanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social OrientationDokument8 SeitenSocial OrientationSunilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Market in Sports-Labor Market of Commercial Clubs: Paper 6Dokument8 SeitenMarket in Sports-Labor Market of Commercial Clubs: Paper 62k2j2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Original ReferencesDokument4 SeitenOriginal ReferencesGirişimci PezevenkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Ambush Marketing and Sponsorship Effects A Football Consumer Response ApproachDokument24 SeitenMeasuring Ambush Marketing and Sponsorship Effects A Football Consumer Response ApproachCheney LinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Casino Gambling As Local Growth GeneratiDokument44 SeitenCasino Gambling As Local Growth GeneratiNG COMPUTERNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums SEDokument4 SeitenThe Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums SETBP_Think_TankNoch keine Bewertungen

- 107 Colum LRev 257Dokument47 Seiten107 Colum LRev 257Liu YuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13.2.2 Vanderleeuw Et AlDokument44 Seiten13.2.2 Vanderleeuw Et AleknaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro To Sport MarketingDokument24 SeitenIntro To Sport MarketingshashankgowdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abratt IJA 1989Dokument13 SeitenAbratt IJA 1989mishrapratik2003Noch keine Bewertungen

- Literature On CSRDokument23 SeitenLiterature On CSRrehanbtariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Event sponsorship as a value creating strategy for brandsDokument12 SeitenEvent sponsorship as a value creating strategy for brandsSamebo ManiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Are New Stadiums Worth the Public CostDokument5 SeitenAre New Stadiums Worth the Public CostMichelleMauricioPaduaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Game On: How The Right of Publicity, Legalised Gambling and Fair Pay To Play Laws Are Changing US Professional and Amateur SportsDokument12 SeitenGame On: How The Right of Publicity, Legalised Gambling and Fair Pay To Play Laws Are Changing US Professional and Amateur SportsVIVEKANANDAN JVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brock Denton StatementDokument1 SeiteBrock Denton StatementWCPO 9 NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review of Corporate Social ResponsibilityDokument25 SeitenLiterature Review of Corporate Social ResponsibilityRatul KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Corporate Social Responsibility DebateDokument37 SeitenThe Corporate Social Responsibility DebateSteve Donaldson100% (1)

- SSRN Id3622662Dokument38 SeitenSSRN Id3622662Eve AthanasekouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sports Sponsorship in AthleteDokument7 SeitenSports Sponsorship in AthleteZulfadhli AtemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Designing A Neighborhood-Based Sports Marketing Model For Small VenuesDokument15 SeitenDesigning A Neighborhood-Based Sports Marketing Model For Small Venuesindex PubNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of Mumbai: Roll No.26Dokument45 SeitenUniversity of Mumbai: Roll No.26Nitesh NagdevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sports Marketing Chapater 5Dokument25 SeitenSports Marketing Chapater 5Louana DavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Competition Law On Intellectual Property LawsDokument21 SeitenImpact of Competition Law On Intellectual Property LawsNikhil KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Myth of Social Investing: Jon EntineDokument17 SeitenThe Myth of Social Investing: Jon EntineRanulfo SobrinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Film Tax CreditDokument12 SeitenFilm Tax CreditThe Capitol PressroomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter6.charitable TrustsAuthor(s) - Rosalind MalcolmDokument25 SeitenChapter6.charitable TrustsAuthor(s) - Rosalind MalcolmRicha KunduNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Social Responsibility: An Economic FrameworkDokument23 SeitenCorporate Social Responsibility: An Economic FrameworkTriadi Akbar WijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Convention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American CitiesVon EverandConvention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American CitiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipVon EverandBusiness Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Just Online Registration Receipt For Transaction - 106682Dokument3 SeitenJust Online Registration Receipt For Transaction - 106682Mohamad Adli AbdullahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agrostar Business Model Canvas Ver 1.1Dokument5 SeitenAgrostar Business Model Canvas Ver 1.1Vircio FintechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview Checklist - Head Butler - Butler Manager - Club Floor ManagerDokument12 SeitenInterview Checklist - Head Butler - Butler Manager - Club Floor ManagerRHTi BDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quality Models CompleteDokument20 SeitenQuality Models CompleteUsama AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internship Report On Vendor Payment OFDokument51 SeitenInternship Report On Vendor Payment OFLakshmi SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economy Book IndexDokument14 SeitenEconomy Book Indexraanaar0% (2)

- STS Product Pitch - Final VersionDokument2 SeitenSTS Product Pitch - Final VersionhelloNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 QuizDokument23 Seiten1 QuizThu Hiền KhươngNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03ebook Energia EngDokument38 Seiten03ebook Energia EngFelipe Adolfo Carrillo AlvaradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proforma Balance Sheet with Financing OptionsDokument6 SeitenProforma Balance Sheet with Financing OptionsJohn Richard Bonilla100% (4)

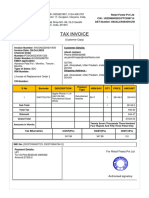

- Tax Invoice: 1 Dwc7Dl7Gv Apple Iphone 11 (4 Gb/128 GB) Refurbished Good White Refurbished Mobiles 8517 1 28149.0 28149.0Dokument2 SeitenTax Invoice: 1 Dwc7Dl7Gv Apple Iphone 11 (4 Gb/128 GB) Refurbished Good White Refurbished Mobiles 8517 1 28149.0 28149.0Nitesh NishantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Index Funds VS StocksDokument46 SeitenIndex Funds VS StocksTim RileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSP - Monetary Board PDFDokument36 SeitenBSP - Monetary Board PDFDwd DinalupihanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ensuring pay equity through job evaluation and compensation plansDokument6 SeitenEnsuring pay equity through job evaluation and compensation plansMichelle Prissila P PangemananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 12 PDFDokument15 SeitenChap 12 PDFTrishna Upadhyay50% (2)

- INVENTORIES AND INVENTORY VALUATIONDokument29 SeitenINVENTORIES AND INVENTORY VALUATIONCarmela BuluranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutorial 02 2Dokument22 SeitenTutorial 02 2Raymond LeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cec - Arellano Letecia PDokument1 SeiteCec - Arellano Letecia PCHE Financial and Accounting Section UP DilimanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peasant MovementsDokument2 SeitenPeasant MovementsD M KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 Are Financial Markets EfficientDokument7 SeitenChapter 6 Are Financial Markets Efficientlasha KachkachishviliNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINA 365 Fall 2016 SyllabusDokument6 SeitenFINA 365 Fall 2016 SyllabusKent NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Behav and Emerg Tech - 2019 - Zhao - Technology and Economic Growth From Robert Solow To Paul RomerDokument4 SeitenHuman Behav and Emerg Tech - 2019 - Zhao - Technology and Economic Growth From Robert Solow To Paul RomerRizki AlfebriNoch keine Bewertungen

- P&G & UnileverDokument61 SeitenP&G & UnileverBindhya Narayanan Nair100% (1)

- Essential Entrepreneurship Skills for Small Business ManagementDokument13 SeitenEssential Entrepreneurship Skills for Small Business ManagementLokesh GargNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final PPT Services MarketingDokument18 SeitenFinal PPT Services MarketingShailendra PratapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caiib-Bfm-Case Studies: Dedicated To The Young and Energetic Force of BankersDokument2 SeitenCaiib-Bfm-Case Studies: Dedicated To The Young and Energetic Force of Bankersssss100% (1)

- The Main Principles of Total Quality Management: Andrei DiamandescuDokument7 SeitenThe Main Principles of Total Quality Management: Andrei DiamandescuipraoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thailand's Digital Future: Data, AI and Smart CitiesDokument247 SeitenThailand's Digital Future: Data, AI and Smart CitiesDavid GalipeauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whyte Chemicals Europe Interview Document-1Dokument4 SeitenWhyte Chemicals Europe Interview Document-1Toni KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- NBP Funds: NBP Aitemaad Mahana Amdani Fund (NAMAF)Dokument1 SeiteNBP Funds: NBP Aitemaad Mahana Amdani Fund (NAMAF)Sajid rasoolNoch keine Bewertungen