Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Greve - When PPP Fail

Hochgeladen von

mametosaurusCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Greve - When PPP Fail

Hochgeladen von

mametosaurusCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

WHEN PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FAIL

- THE EXTREME CASE OF THE NPM-INSPIRED LOCAL GOVERNMENT OF FARUM IN DENMARK

Carsten Greve Department of Political Science University of Copenhagen Rosenborggade 15 DK-1130 Copenhagen e-mail: cg@ifs.ku.dk and Niels Ejersbo Department of Politicial Science & Public Management University of Southern Denmark, Odense Campusvej 55 DK-5230 Odense M e-mail: niels@sam.sdu.dk

Paper for Nordisk Kommunalforskningskonference 29 November - 1 December 2002 Odense, Denmark

Abstract: Public-Private Partnerships (PPP's) have been hailed as the latest institutional form of co-operation between the public sector and the private sector. PPP's are defined as co-operation between public and private actors over a longer period of time, where risk, costs and resources are shared in order to produce a service or a product. The paper considers what happens when PPP's fail. The case of Farum local government in Denmark is examined. Farum is known for its radical use of NPM-reforms and PPP arrangements. Farum local government has experienced a series of events in 2002 which is set to be the most spectacular scandal in the history of Danish public administration. The results so far in 2002: The mayor is expelled from office. Income tax for citizens will rise 3,2% in 2002. Farum is put under administration by the Danish Ministry of Interior and cannot decide its own economic fate. Several investigations have been launched, including a police investigation and a Parliamentary investigation. The paper asks whether the scandal in Farum was connected to the use of PPP arrangements?

Number of words: 6397

INTRODUCTION Public-Private Partnerships (PPP's) have been hailed as the latest institutional form of co-operation between the public sector and the private sector (Savas 2000). PPP's can be defined as "co-operation of some durability between public and private actors in which they jointly develop products and services and share risks, costs and resources which are connected with these products or services" (Van Ham & Koppenjan 2001: 598). The institutional forms of PPP's vary from close contracting out cooperative efforts to infrastructure projects for building and operating new physical facilities such as schools, tunnels, bridges or sports arenas. A PPP is still a "contested concept" with many different meanings attached to it (Linder, 1999). PPP's are viewed by private companies as alternatives to "raw" contracting out (ISS, 2002). Others view PPP's as financial arrangements where the utility for the public sector is difficult to see, and which will exclude competition in the long run. PPP's are only beginning to be used in public sectors around the globe. Most experience have been gathered in the UK (IPPR 2000), the USA, and Australia, but other countries have followed suit (Osborne, ed. 2000) PPP's are mostly connected with experimental "front runner" or "best run" local governments that seek to explore new ways to deliver better public service to lower costs. The local government of Farum in Denmark has been one of the world's most active local governments in experimenting with PPP's. In the 1990's, Farum was among the candidates for the title of the "Best Run Local Government in the World" sponsored by the Bertelsmann Foundation in Germany. Winners were Phoenix, Arizona, and Christchurch, New Zealand. Since the 1980's, the charismatic mayor, Mr. Peter Brixtofte, has enjoyed an overall majority in Farum. Brixtofte has followed an active NPM/marketization strategy relying on contracting out and, later, PPP's for delivery of public services. In 2000, Farum local government had contracted out its kindergartens and elderly homes, made a sale-and-lease-back deal for its water supply and school buildings plus entered into BOOT (Build Own Operate Transfer or Build Own Transfer) models for the construction of the sports arena Farum Arena and the soccer stadium Farum Park as well as a nautic center called Farum Marina. In early 2002, a major scandal erupted in Farum with damaging consequences for the local government and its mayor. It was set off by newspaper revelations of excessive wine bills from restaurants, but soon grew much bigger than that. The "casualty list" in November 2002 looks as follows: The mayor has been expelled from office. The local government is in effect administered economically by the Ministry of the Interior. Private companies have paid money to the soccer club in exchange for securing contracts with the local government. There are several investigations going on, including a police investigation and a Parliamentary commission. Farum has changed mayor three times since February 2002. The local government's finances are now in ruins. The local government taxes will be raised by 3,2 % in 2003. The former mayor may face criminal charges. The council will also face possible criminal charges because its members did not control the mayor's actions. The local chapter of the political party, the Liberal Party, has been split into two separate chapters. The wider implications for local democracy in Denmark have yet to be considered. The PPP deal is at the heart of the matter. It was the PPP deal with the construction of the soccer stadium and the sports arena, and the missing money from those deals, that triggered the development, which led to the mayor's fall and the local government scandal. In this paper, the following questions will be examined: Why did PPP's fail in Farum? What are the lessons from Farum for future PPP deals? The main argument of the paper is that a contractual governance perspective will help us to understand why the local government scandal took place. Managing a wide range of contracts is complicated. The mayor and the local council must know what it wants to buy, whom to buy from and to be able to judge what is has bought. The structure of the contractual governance scheme in Farum was too complex for the mayor to oversee. Therefore, an important lesson is to be learned from the Farum case and that is to make PPP deals more transparent and involve the relevant stakeholders more. A further argument is that PPP's were too new politically and legally for the central government level. Central government did not have sufficient rules to deal with experimenting local governments like Farum. There is also an important lesson here to be learned for central government and that lesson is to be better prepared and gear and prepare the legislation for innovative local governments. When the central government did act, it acted more or less in panic and simply stopped the PPP deals overnight.

THE PROMISES AND PROBLEMS OF PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS PPP's can be defined in broad terms or in more narrow terms. In broad terms, it simply means any form of cooperation between organizations in the public sector and the private sector, usually meaning "cooperative ventures between the state and private business (Linder, 1999, 35). Contracting out can be viewed as a form of PPP in this perspective (Savas, 2000). A more narrow conception will look at PPP's as distinct from contracting out. Contracting out means principalagent relationship between public purchasers and private providers. The relationship is characterized by mistrust as principals and agents both seem to maximize their utility. Contracts are usually for shorter periods of maximum five years. PPP's means cooperation based on trust where the parties to the contract are on equal terms. Contract periods are long term, sometimes up to 30 or more years. PPP's have the following elements: a business-like relationship, common decision-making procedures, risks sharing, and long term contractual relations. A PPP can be defined as ""co-operation of some durability between public and private actors in which they jointly develop products and services and share risks, costs and resources which are connected with these products or services" (Van Ham & Koppenjan 2001: 598). PPP's focuses on cooperation of entities: "The hallmark of partnerships is cooperation, not competition; the disciplining mechanism is not customer exit or thin profit margins, but a joint venture that spreads financial risk between private and private sectors" (Linder, 1999: 35). The institutional form of a PPP varies. The institutional form can be a formal joint-venture company, an agreement to cooperate or simply a new organization where both public and private participates. Some include cooperation between public organizations and voluntary organizations as distinct forms of partnerships (Salamon, 1996). Savas (2000) lists a number of possible types of PPPs. This list include infrastructure projects like BOOT, BOT, BOO and other models. These models are highly complex and rest on extensive risk sharing between the parties in the partnership. Central to the definition and understanding of PPP's is risk sharing. The parties to the contract are interested in gain sharing (Domberger, 1998) and they cannot specify all future requirements in a contract. The partnership contract is therefore a relational contract in Williamson's (1996) sense of the term. Some points must be left open to future negotiations as new contingencies arise. Public organizations must confront a number of risks when they enter a PPP: substantive risks financial risks, risk of private discontinuity, democratic risks and political risks (Van Ham & Koppenjan 2001: 599-602). Public organizations must beware that private parties do not transfer their own financial risks to the public sector. Another risk to take for the public organization is not to be able to understand the complex financial deals private parties present to the public sector. Likewise, private parties run risks, especially by entering into a contract with a politically led organization, which may have new leadership by the next local council election. If there are risks, why consider entering into PPP's? PPP's hold certain promises for local governments. The first promise is that PPP's will limit the local governments' financial situation. Either by injecting cash into the local government's finances, or by providing capital, which can be used to build or construct new physical facilities for the use of the local government's citizens. The second promise is that public services can be delivered more effectively and at a lower price. This is of course a highly debatable point. Third, PPP's promise innovation of public service delivery will take place. Access to the expertise of the private sector will be provided through use of PPP's. For the private parties, the attraction lies in gaining new markets and getting new investment opportunities (Van Ham & Koppenjan, 2001: 597). Risk management is a central part of any PPP arrangement, and the partners to the contract must recognize the risks involved, try to reduce them, and allocate the risks to the parties most prepared to take them on (Van Ham & Koppenjan, 2001: 601). PPP's as infrastructure projects have been criticized from several perspectives. First, is the meaning of local government to "manage risk"? Traditionally, public bureaucracy has been risk-adverse almost by definition. Equality before the law, fair treatment for all and legally based decision-making has been the hallmark of what has been called "the traditional model of public administration" (Hughes, 1998). The point is that local governments should avoid risk-related projects and stick to traditional and competent administration. Risk-taking is for private sector companies and not local governments. Second, the democratic accountability of PPP's are not sufficiently worked out yet. "The deal" in PPP in arrangements is not easily transparent (Hodge, 2002). How can a mayor and a local council enter into a 2o or 30-year contract is held accountable? What the mayor does is to constrain future mayors and local council members in their decision-making capabilities. Third, The financial and juridical elements are complex and require insights from a lawyer perspective or a financial analyst perspective. Should the future of local government finances be taken out of traditional economists' hands and be given to contract lawyers and financial investor experts?

PPP'S IN FARUM AND THE FARUM SCANDAL IN 2002 PPP's in Farum PPP's in the broad sense of the term has been a key strategy for Farum local government since the early 1990's. Contracting out has been used extensively. Farum contracted out its kindergartens and elderly homes to the Danish international company, ISS. In the late 1990's, Farum local government was the first local government in Denmark to contract out administrative work at the city hall to a private company (one of the big five auditing companies). In one of the several books the mayor has written (Brixtofte, 2000), the policy of contracting out policy and PPP's was hailed as revolutionary in a Danish public service context. PPP's in the narrow sense of infrastructure projects and deals have been used since the mid-1990's in Farum. Sale-andlease back was a preferred policy instrument. The local government sold its water company, waste water facilities, schools and swimming pools and leased them back. In 2000 the Ministry of the Interior put a stop to the sale-and-leaseback arrangements. The mayor pushed forward three big construction projects in the late 1990's: a 3500 capacity indoor sports arena (Farum Arena), a state-of-the-art soccer stadium (Farum Park) and a nautic marina (Farum Marina). The financing of the projects came from private finance sources. The main finance institution was the FIH-institute, which financed both three major infrastructure projects. The deal was that Farum would obtain loans, let the FIH-institute build, own, and operate the facilities and turn the facilities over the Farum local government after 20 years. The great discussion among politicians, administrators and citizens has been what are the financial risks involved in the deal. The opinion were divided into two camps; Farum local government executives (foremost the mayor) who was enthusiastic about the idea and who had the support of his majority party. The political opposition in Farum plus skeptical citizens' groups. Also business magazines have been skeptical and has examined the foundations of the deal and found them fragile at best In a now famous passage, the business magazine editorial accused the mayor of gambling in the casino with taxpayers money (an accusation that was dismissed by the mayor and his adviser at the time). The Farum Scandal in 2002 On 6 February 2002, the daily tabloid newspaper, BT, carried a headline story on its front-page announcing that mayor Peter Brixtofte of Farum had been picking up huge restaurant bills for red wine for over 8000 DKK a bottle. One bill alone had "red wine" for 64.000 DKK for the mayor and four of his friends for one evening. There had been numerous newspaper stories of the Farum experiment in newspapers before that, but none other story had produced "hard evidence". BT had hard evidence in the form of the restaurant bills and witness statements from former employees at the restaurant. Among politicians and journalists, the drinking habits of Peter Brixtofte had been widely known, but few had acted upon the knowledge, for example by publicly telling Brixtofte to quit drinking. At first therefore, it seemed like "a good news story", but nothing more than that. In the following weeks, the scandal grew at a rapid pace. Further investigations showed that the local government had paid excessive bills, when the bills were actually connected to the soccer club - in which the mayor was also, chairman and shareholder. A civil servant in Farum then disclosed - moved by the opportunity to tell other mismanagement stories - that he had been forced to withhold a payment for a building site in Farum which triggered a bonus check for 325,000 DKK to a close friend of the mayor. According the civil servant, the mayor had made a clear decision and ordered the civil servant to withhold the payment so a check would be issued. Around the same time, the Complaints Council for Contracting Out announced that the tender process in which FHI had won the right to finance the infrastructure-projects of the soccer stadium and the sports arena had not followed EU-rules on tender and contracting out. Farum had claimed it was not the owner of the facilities because FIH had taken them over in the PPP deal. FIH as the owner was not obliged to follow the EU-tender rules. But the Complaints Council for Contracting Out ruled that Farum was, in effect, still the owner (because FIH was not allowed to make alterations to the facilities without the consent of Farum local government). A relatively huge sum of money had to be deposited. Farum local government was not allowed to use the money in its daily running of the local government. Technically speaking, this was not a "sale-and-lease-back" arrangement although it has been called that in the media and by the Complaints Council for Contracting. Instead, the construction of Farum Arena and parts of Farum Park was another PPP-type, the "build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT)"-model. Farum had sold the ground where Farum Arena was to be. FIH build the sports arena, owns it and operates it until it - in 20 years time - will transfer it to Farum local government. FIH finances the deal through a 20-year loan, but Farum local government has to fund it through its lease of the facilities. Because the

Complaints Council ruled that it was not legal according to EU tender rules, the claim from the citizen who made the case is that 20% could have been saved (the rule of thumb for contracting out - disputed by Hodge, 2000). Therefore, the loan could have been 20% cheaper. This piece of news came at a particular bad time for Farum as the mayor had recently bought a disembarked army base with the intention of turning the former base into profitable new housing estates. The mayor needed the money from the PPP deal with FHI because it would take some time to constructing and selling the housing estates. When all this took place, the mayor was located in the Canary Islands in Spain where he was taking a holiday. On 7 February 2002, the day after the "red wine story", the mayor had taken a sick leave, and on 8 February he flew to the Canary Islands.. On the Canary Island of Lanzarote friends surrounded him, as senior citizens in Farum had been given a free trip to the Canary Islands. In the BT newspaper, it was revealed how the senior citizens' trips were "money machines" for the local government, because the Travel Company paid sponsorships to the soccer club where the mayor was chairman. The press soon flew out and for a week or so, Brixtofte conducted interviews and commented on the situation back in Farum, from the poolside of his hotel in the Canary Islands (this lasted until his attorney advised him to come home and face the allegations and his critics). The scandal evolved in a number of surprising ways. The papers from the civil servant who had complained about the mayor were removed when the head of the mayor's secretariat, Steen Gennsmann, on 10 February broke into the office of the civil servant in the middle of the night and removed a number of papers and filing reports that was the proof material. On the evening of the 11 February, the police began an action where the town hall was ransacked and more than 50 removal boxes full of paper were taken away as well as several computers. On 14 February it was revealed how the Farum local government charged too high prices from companies involved in the infrastructure projects only to transfer the money the local soccer club. On 18 February, it was revealed that the mayor had secured a bank loan on 250 million DKK without consulting the local council. Allegedly, the local government's debt had grown so much that the payment of salaries to the employees in Farum local government had been at stake. At first, the mayor denied that he had secured the loan, but later on, the fact was confirmed. Later in February, it was disclosed how the mayor and his chief administrative officer had paid money of up to 9 million DKK to a close friend of the mayor in the building industry. The Ministry of Interior had not been taking any kind of action in the first days of the scandal. But on 20 February, the minister of the interior announced that he would put Farum local government "under administration" because of the disastrous economic situation. The decision was verified later on in the spring. A twist to the minister's ruling is that the minister is a former ally of the mayor. They belong to the same party. They both encouraged market-solutions to the public sector. The minister of the interior was previously vice-mayor in the local government of Grsted-Gilleleje, which is known for its use of market-type mechanisms, and before becoming minister, he was mayor of the regional government of Frederiksborg (where Farum local government is situated). The minister had in his local government days been ardent supporter of public-private partnerships and competitive government. On 21 March, the mayor is finally suspended from office after lengthy negotiations on how to make a suspension, and who to replace him. The cause that is used is the bank loan of 250 million DKK, which the mayor has not told the local council about. A new mayor, Paul Watchell, from a Citizens' List, replaces Brixtofte as mayor, but only for a short while. In his absence in February, Henrik Jerner, a liberal party member, was stand-in mayor for a short period. The minister of the interior confirms the suspension of the mayor on 6 May 2002. As a result of the economic transactions and the disastrous economic situation, the minister of the interior has confirmed Farum's local council's decision to raise personal income tax by 3,2% for 2003. Farum local government will go from being one of the cheapest local governments to live in to be one of the most expensive local governments in Denmark. Various investigations have been launched into the Farum scandal: 1) The police are investigating the mayor's actions. Charges have been brought against the mayor for unlawful obtainment of a bank loan without the knowledge or the consent of the local council 2) An attorney investigation is examining whether anything illegal has been happening in the transactions of the local government in Farum. 3) The opposition parties in the Danish Parliament have decided upon a Parliamentary "investigation commission" which will begin its work in 2003. The purpose of the commission is to make sure that no stone is left unturned in the investigation of what happened in Farum with an explicit aim of preventing a similar scandal to occur in the future (Forslag til Folketingsbeslutning om Undersgelseskommission om Farum, 1. Behandling 20. November 2002 i Folketinget).

WHEN PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS FAIL: LESSONS FROM THE CASE OF FARUM PPP's in Farum has failed in the sense that one arrangement was found in violation of EU-regulations for tender and contracting out, the government (the Ministry of the Interior) effectively banned the sale-and-lease-back arrangements in Farum's version. Both types of PPP arrangements are not working as first intended by the local government. In contracting out, private sector providers have paid money to sponsorships for the soccer team in exchange for contracts for public service delivery. When the company, ISS, declined to pay sponsorships for the soccer club, the mayor stopped cooperation with ISS as a contractor the local government's kindergartens. In a wider perspective, PPP's have contributed to a low moral in the local government. The argument in the following section refers to the points introduced in the theory section. We will look at risk taking and regulation (risk-taking without constraints or risk-taking in a regulated environment?), the nature of the PPP deals (simple or complex?) and democratic accountability (clear accountability structure or insufficient accountability structure?) Clash between central rules and local innovation When Farum began on sale-and-lease-back arrangements, the concept was very little known in the Ministry of the Interior and the State Regulation Council that regulates local government affairs. Suddenly, Farum got all this money in its hands, which it could pay for new public services. The Ministry looked upon the activities with some bewilderment. Gradually, the thought dawned on the Ministry that sale-and-lease-back arrangements could be a potential danger for the national economic policy if local governments were allowed to sell and then lease back their physical assets. More and more local governments were beginning to follow Farum's model in the 1990's. The daily newspaper, Politiken, counted 13 local governments that had experimented with PPP's. The Ministry of the Interior decided in the end that it would not allow sale-and-lease-back arrangements as Farum had introduced them. Instead, local governments had to deposit the money from sale-and-lease-back arrangements thereby making it indifferent to the local government to pursue with sale-and-lease-back arrangements or not. This is a case of central rules not being up to date or geared for an innovative practice in local governments. Instead of designing new rules to meet the challenge of PPP-arrangements, the central government responded with a preemptive strike - to forbid the kind of arrangements that Farum was promoting. In the case of the BOOT-model for constructing the new indoor sports arena and the soccer stadium, central rules again collided with new local government practice. Farum local government had signed a contract with the finance institute FIH that gave FIH the right to a greenfield site in the city of Farum with a clause saying that FIH should construct a new indoor stadium. In another contract, the construction of the new part of the soccer stadium was also handed over to FIH. The controversial issue in this case was if Farum local government then violated the EU tender and contracting out rules because the contract was not put out to tender because Farum had transferred the ownership to FIH by Farum local government. In Farum's argument, the local government was not responsible for the constructing of the sports arena or the stadium, but had left it to FIH to do the work. The missing part is the bidding process, which Farum got out of because it placed FIH as the constructor and owner of the stadium. FIH might have been the winner of the bidding process, but we cannot know if Farum could have got the sports arena and soccer stadium for a cheaper price, because the contract was not put out to tender. Again we see a clash between centrally laid rules and new local government practice. In this case, the rules for EU-tender are reasonably clear, and it could be argued (as the Complaints Council did in its ruling) that Farum was, in effect, the owner of the sports arena and soccer stadium, and therefore a bending of the rules was not acceptable. The two cases raise the broader question of the centrally laid rules and the new local government practice with PPP's. It shows that the rules are not designed to PPP arrangements. PPP arrangements have to be fitted into the traditional set of rules (in the case of EU tender rules), or have to be evaluated in no particular context, as central government has not any previous position or ruling to rely on (in the case of the sale-and-lease-back arrangement). The former mayor of Farum has made the argument several times that the regulatory system is not sufficiently prepared to deal with local governments that introduce new practices in public service delivery. In a certain way, the mayor is right - that adequate regulation is missing. However, this is no excuse for then bending or violating existing rules.

Closed deals The second point relates to the nature of the contract that Farum local government entered into with the finance institute FIH and other contractors. Farum has not led an open doors policy. Access to relevant documents has been hard to get for the opposition in the local councils, for citizens' groups and for journalists. The mayor has not been forthcoming in revealing details and conditions in the contracts that he as a mayor has signed on behalf of the local council The financial and juridical implications of the deals have not been clear. In 1999, the newsmagazine, Brsens Nyhedsmagasin, tried to assess the risk Farum was taking with the new PPP-arrangements. The mayor and his economic adviser defended their contractual construction vigorously. The newsmagazine claimed - also in an editorial that the calculations and the financial forecasts were not safe - and that the mayor was, in effect, gambling with (future) tax payers' money. For non-financial experts, the arguments were hard to follow as it mainly concerned the judgement of future rent developments. These are highly detailed and complex financial arguments, and only a handful of financial experts will be able to penetrate the logic and the construction of the financial PPP arrangements. Lack of attention to democratic accountability The third point is that democratic accountability has not been considered properly in the Farum case. The mayor has been formally accountable to the local council. In local governments, the prospect of being ousted from office by the voters of Election Day has been the primary institution for effective democratic control. But since the mayor has enjoyed an overall majority in several periods in office and had many loyal followers and admirers of his personal charisma, the councilors in his own party did not question the thinking behind the PPP deals. So the formal democratic accountability within the local council was not being effective in regulation the behavior of the mayor and holding him to account for his actions in the Farum case. Other institutions of democratic control through auditing, ombudsman control and regulation of local government activities have been neglected to a certain extent. The bodies the mayor had to give account to have not lived up to their responsibilities. The auditor that audited the finances of the local governments has not detected any wrongdoings or mismanagement in its accountancy reports. The other body is the State Regulatory Council, which is central government institution that regionally have as their duty to oversee matters and regulate at the local government level. Despite a huge number of expressions from concerned citizens and citizens' groups, the State Regulatory Council has not been able to correct the mismanagement and wrongdoings in the local government of Farm. Only recently has the Ombudsman been allowed to handle local government issues. The institutions of auditing at the local level and the regulatory system have been undergoing change or preparing for change while Farm local government experimented with PPP's. Administrative audit ("forvaltningsrevision") only recently has been made compulsory for local governments also (administrative audit has been a feature in the audit of central government for years). Administrative audit had not found its own position in the local government yet. However, the financial audit part should have detected some of the wrongdoings (including unlawful obtainment of bank loans). In the case of the State Regulatory Body, there has been a government white paper on regulation of local governments - and the government has for some time advocated an overhaul of the regulatory structure. In effect, various ministers who made it clear they wanted a new regulatory structure have undermined the work of State Regulatory Body. The State Regulatory Body has not enjoyed sufficient legitimacy for several years. This made it easier for the mayor to dismiss the rulings and judgements of the State Regulatory Body (why bother taking their rulings serious if they are going to be abolished anyway). Farum local government exploited the gap in the regulatory system by pushing forward with reforms that no institution was able to evaluate properly because of insufficient expert knowledge and no legitimacy. Did PPP's lead to low ethics? There is a wider issue that goes beyond the breaking or bending of existing rules. Did partnerships and contracting that implied detailed negotiations with private sector companies lead to low ethical standards and consequently to unacceptable and unethical behavior on the part of the mayor and his close advisers? There is an argument to be made for extensive use of PPP's will lead to too close connections between the local government and private providers. In the case of Farum, the mayor builds up close relationships with private providers of public services in the areas of kindergartens and elderly homes. Negotiations with private providers mean many meetings and close dealings. To secure a contract for a company, company executives might be willing to engage in new relationships.

In the Farum case, private providers agreed to pay for sponsor fees to the soccer club in exchange for contracts with the local government. A close contact was also established with a "big five" auditing company when it started to deliver administrative services to Farum local government. With the infrastructure PPP arrangements, Farum build a close relationship with the finance institution FIH, which have provided the finance for Farum's big projects; the sports arena and the soccer stadium. The Complaints Council's decision showed that the relationship was too close for comfort, and that Farum should have put the tender for building the sports arena and soccer stadium out to the open market. The implication of the argument is that close negotiations for public service delivery for longer periods of time can make the relationship between public sector organizations and private sector organizations too close and the partnership will then end in abuse towards citizens and taxpayers. As Adam Smith once noted, if you put too many people of a profession together in a room, it will not be long before they put their own interests before that of the general public. Against this argument is the fact that the mayor had been in office since the 1980's and had enjoyed an overall majority. "Power corrupts" and the mayor had simply been too long in office. The Farum scandal had more to do with traditional power politics than with PPP's and contracting. The mayor would have shown a similar behavior even if Farum had not collaborated with the financial institution to construct the new stadium. CONCLUSION This paper has considered the spectacular scandal in the Danish local government of Farum in Denmark, which has evolved during 2002 and continues to amaze the public, administrators, and politicians. The scandal is also an embarrassment to the national government, which is promoting marketization and partnerships with the private sector. First, the Farum case has shown that infrastructure PPP's lead to a potential clash between local government ambitions and central government rules. Before an adequate legislation is in place, PPP's are likely to lead to failure in the sense that they cannot be carried out as planned by local governments. Second, the Farum case shows that the financial deals in infrastructure PPP's are complex and requires financial expertise to judge if the deals are healthy for the local government economy. PPP's involves risks and need a risk management effort. In the long run, it is debatable if the fate of local government economy should be left to financial analysts instead of political judgement. Third, the Farum case shows that democratic accountability is fragile in PPP's. Democratic accountability cannot rely solely on election days, but must be supplemented by renewed democratic institutions of control such as auditing, the ombudsman, and regulatory council. All of these institutions must be prepared for local governments that are not only traditional administrative units, but also risk-taking, innovative managerial minded local governments. The control side has to be as dynamic as the innovative side of local government activity. The policy implication is that PPP's must be treated with care. What does the future hold for PPP's? Several authors have noted how a lack of competition is unhealthy for publicprivate co-operation. Van Ham & Koppenjan (2001, 606) asks "how to retain competition in partnership without lapsing into contracting out?" One strategy could be to try "serial organizational monogamy" (Greve & Ejersbo, 2002). Serial organizational monogamy describes a relationship between public and private organizations which is build on trust, but only for a limited period of time. The main challenge in PPP's in their current form is that they are set to last too many years (20 to 50 years), which is difficult to work with for public managers and politicians who usually have much shorter time spans on their mind. Serial organizational monogamy means that public sector organizations and private sector organizations can co-operate - and even enter into institutional forms of partnerships - but not necessarily to "death do them part" - or rather till the 30 or so year contract expires. The contract horizon must be much more focused for public managers and politicians to work with it. As companies start to refer to "raw contracting out" when they want to engage in longterm partnerships with local governments, the local governments must be aware of the danger of tying itself to one professional partner for too long time, which will squeeze out competition. For a market to work, there has be some sort of competition , or at least the prospect of competition. The right way to pursue for local governments is to acknowledge that a partnership can take place, but also make it clear that competitors are waiting in the wings, if the partnership does not turn out as planned. Serial organizational monogamy can be a viable alternative to both traditional contracting out and new arrangements with partnerships.

REFERENCES Brixtofte, Peter.2000. Et opgr med 13 tabuer - en handlingsplan for Danmark. Kbenhavn: Brsens Forlag. Domberger, Simon. 1998. The Contracting Organization. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Ejersbo, Niels & Greve, Carsten. Eds.. 2002. Den offentlige sektor p kontrakt. Brsen, Brsens Forlag. Greve, Carsten & Ejersbo, Niels. 2002. "Serial Organizational Monogamy. Building Trust Into Contractual Relations". International Review of Public Administration Vol. 7. No. 1., pp. 39-51. Hodge, Graeme.2000. Privatization. An International Review of Performance. Westview Press, Boulder, Co. Hodge, Graeme 2002. Contracting Government Services. Some Global Research Insights on Contracting Out and Public-Private Partnerships. Guest lecturer, Copenhagen, September 2002. Huhges, Owen E. 1998. Public Administration and Management 2.edition. London, MacMillan. Institute of Public Policy Research. 2000. Building Better Partnerships. London. Linder, Stephen.1999. "Coming to Terms with the Public-Private Partnership. A Grammar of Multiple Meanings" American Behavioral Scientist Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 35-51 Osborne, Stephen. Ed. 2000. Public-Private Partnerships. London, Routledge. Salamon, Lester. 1996. Partners in Public Service. John Hopkins University Press. Savas, E.S. 2000. Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships. New Jersey, Chatham House. Van Ham, Hans & Koppenjan, Joop. 2001. "Building Public-Private Partnerships" Public Management Review Vol. 4, No. 1. Pp. 593-616. Williamson. Oliver E. 1996. The Mechanisms of Governance. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

On Farum local government. Article Database on Contracting Out from Project on "The Public Sector Under Contract": file on Farum www.dr.dk www.bt.dk

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 2017 - Twenty Years of Ecosystem Services - How Far Have We Come and How Far Do We Still Need To Go PDFDokument16 Seiten2017 - Twenty Years of Ecosystem Services - How Far Have We Come and How Far Do We Still Need To Go PDFStephaDuqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- CIPFA - Leading-Internal-Audit-In-The-Public-Sector (2019)Dokument18 SeitenCIPFA - Leading-Internal-Audit-In-The-Public-Sector (2019)mametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20 Years of MHP in Indonesia and its Future OutlookDokument14 Seiten20 Years of MHP in Indonesia and its Future OutlookmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Hoyos - The Effect of Trade ExpansionDokument26 SeitenDe Hoyos - The Effect of Trade ExpansionmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appelbaum - Performance AppraisalDokument16 SeitenAppelbaum - Performance AppraisalmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Format For Reviewing Journal ArticleDokument2 SeitenSample Format For Reviewing Journal ArticlePiyush Malviya100% (1)

- Sample Format For Reviewing Journal ArticleDokument2 SeitenSample Format For Reviewing Journal ArticlePiyush Malviya100% (1)

- Rich - NAFTA and Chiapas PDFDokument14 SeitenRich - NAFTA and Chiapas PDFmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaoul - Britain PPPDokument12 SeitenShaoul - Britain PPPmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Policy Feedback, Generational Replacement, and Attitudes To State Intervention PDFDokument18 SeitenPolicy Feedback, Generational Replacement, and Attitudes To State Intervention PDFmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bilgin - Historicising Representation PDFDokument27 SeitenBilgin - Historicising Representation PDFmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phumpiu - When Partnership A Viable ToolDokument20 SeitenPhumpiu - When Partnership A Viable ToolmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kotsadam - Laws Affect Attitude PDFDokument13 SeitenKotsadam - Laws Affect Attitude PDFmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cotton - Infrastructure For Urban Poor PDFDokument10 SeitenCotton - Infrastructure For Urban Poor PDFmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crane - Water Market, Result From JakartaDokument13 SeitenCrane - Water Market, Result From JakartamametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaoul - Britain PPPDokument12 SeitenShaoul - Britain PPPmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- The New Governance: Governing Without GovernmentDokument16 SeitenThe New Governance: Governing Without GovernmentmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contesting Global Governance Multilateral Economic Institutions and Global Social MovementsDokument31 SeitenContesting Global Governance Multilateral Economic Institutions and Global Social MovementsmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three New Institutionalisms in Political ScienceDokument22 SeitenThree New Institutionalisms in Political SciencemametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluating Risks of Public Private Partnerships For Infrastructure ProjectsDokument12 SeitenEvaluating Risks of Public Private Partnerships For Infrastructure Projects07223336921Noch keine Bewertungen

- Whose Nation?Dokument11 SeitenWhose Nation?mametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedrich Engels The Great TownDokument22 SeitenFriedrich Engels The Great TownmametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhodes - Understanding GovernanceDokument23 SeitenRhodes - Understanding GovernancemametosaurusNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 51 Raymundo v. Luneta MotorDokument2 Seiten51 Raymundo v. Luneta MotorJul A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Government Gazette - 25th FebruaryDokument8 SeitenGovernment Gazette - 25th FebruaryistructeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commission Chairs Oppose DRC/AC Merger - Beverly Hills Weekly, Issue #659Dokument3 SeitenCommission Chairs Oppose DRC/AC Merger - Beverly Hills Weekly, Issue #659BeverlyHillsWeeklyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law On Cooperatives Gr. 5Dokument7 SeitenLaw On Cooperatives Gr. 5Stephani Cris Vallejos BoniteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pablico vs. VillapandoDokument8 SeitenPablico vs. VillapandoChristine Karen BumanlagNoch keine Bewertungen

- The National Security Agency and The EC-121 Shootdown (S-CCO)Dokument64 SeitenThe National Security Agency and The EC-121 Shootdown (S-CCO)Robert ValeNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Obtain Portuguese NationalityDokument6 SeitenHow To Obtain Portuguese NationalityKarol PadillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Japan China Relations Troubled Water To Calm SeasDokument9 SeitenJapan China Relations Troubled Water To Calm SeasFrattazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industry Security Notice ISN 2014 01 Updated April 2014 UDokument29 SeitenIndustry Security Notice ISN 2014 01 Updated April 2014 UMark ReinhardtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lyndon B Johnson A Colossal Scumbag 2Dokument5 SeitenLyndon B Johnson A Colossal Scumbag 2api-367598985Noch keine Bewertungen

- Frank o Linn JudgementDokument60 SeitenFrank o Linn JudgementAndré Le RouxNoch keine Bewertungen

- WTC Transportation Hall Project 09192016 Interchar 212 +Dokument17 SeitenWTC Transportation Hall Project 09192016 Interchar 212 +Vance KangNoch keine Bewertungen

- 88 Government Vs Colegio de San JoseDokument1 Seite88 Government Vs Colegio de San Josek santosNoch keine Bewertungen

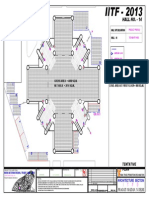

- IITF Hall 14 Layout PlanDokument1 SeiteIITF Hall 14 Layout Plangivens201Noch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Standards 1 - Title, Thesis, Body ParagraphsDokument4 SeitenWriting Standards 1 - Title, Thesis, Body ParagraphsClay BurellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note On Anti-DefectionDokument4 SeitenNote On Anti-DefectionAdv Rohit DeswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Exchange Rates StatisticsDokument25 SeitenFinal Exchange Rates Statisticsphantom_rNoch keine Bewertungen

- Members Contact LoksabhaDokument81 SeitenMembers Contact LoksabhaPankaj Sharma0% (1)

- European Companies in India 2012Dokument290 SeitenEuropean Companies in India 2012India Power Sector Jobs57% (7)

- Alberto Gonzales Files - The Bush Administration V Affirmative ActionDokument10 SeitenAlberto Gonzales Files - The Bush Administration V Affirmative ActionpolitixNoch keine Bewertungen

- M商贸签证所需资料ENGDokument2 SeitenM商贸签证所需资料ENG焦建致Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 of Codralka 1Dokument41 SeitenChapter 9 of Codralka 1Jael LumumbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Ugandan Peacekeeping Troops in Somalia Mark Tarehe Sita' DayDokument6 SeitenNEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Ugandan Peacekeeping Troops in Somalia Mark Tarehe Sita' DayATMISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life of RizalDokument7 SeitenLife of RizalyssaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Disinterested Person - Divina Lane Fullido SitoyDokument1 Seite2 Disinterested Person - Divina Lane Fullido SitoyJaniceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public International Law Project On Use of Force in International LAWDokument23 SeitenPublic International Law Project On Use of Force in International LAWRobin SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Revolution AssessmentDokument11 SeitenAmerican Revolution Assessmentapi-253283187Noch keine Bewertungen

- PINAY Maurice-pseud.-The Secret Driving Force of Communism 1963 PDFDokument80 SeitenPINAY Maurice-pseud.-The Secret Driving Force of Communism 1963 PDFneirotsih75% (4)

- The Great Emu WarDokument1 SeiteThe Great Emu WarSam SamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syariah Islam 3Dokument14 SeitenSyariah Islam 3syofwanNoch keine Bewertungen