Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Haney Group: Can Stocks Hold Up Once Tapering Begins?

Hochgeladen von

jolinelindbergCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Haney Group: Can Stocks Hold Up Once Tapering Begins?

Hochgeladen von

jolinelindbergCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Haney Group: Can Stocks Hold Up Once Tapering Begins?

the haney group, Can Stocks Hold Up Once Tapering Begins?

Source

A lot has changed since the boom days that preceded the 2008 financial crisis, but two things remain surprisingly similar: corporate profits and stock prices.

Both have returned to record territory, which has been good news for investors. But their recovery has been so rapid and has benefited so much from the Federal Reserves intervention that it now poses a challenge: How to keep profits and stocks from sagging once the Fed begins slowly to temper its stimulus, possibly starting this week.

Stock prices and corporate profits stand out because most of the economic backdrop doesnt look nearly as lush as it did back when the housing bubble was still inflating. The economy is growing again, but it is still limping. Unemployment remains high. The property market is far from recovered.

Stock prices and corporate profits, however, already have risen so fast that the pace of their gains is slowing. This is something that often happens when an economic recovery has been under way for several years; this one has been going since 2009. Something similar happened before the financial crisis, when stocks and corporate profits began running out of steam as the property bubble was deflating in 2007.

The real-estate boom was a big motor for stock gains last time around, but it is a sideshow today. This time, the Fed is a big motor for the market and worries focus on what will happen to stocks as that stimulus begins to shrink.

Making things worse, the Fed is getting ready to move at a time when the economies of countries such as China and India have been struggling, Europe is generating little growth and the Middle East is in turmoil. Nervous investors have withdrawn billions of dollars from both stock and bond funds since mid-August, both in the U.S. and in emerging markets, according to EPFR Global, which tracks such flows.

All of this provides an unsettled backdrop for the Fed pullback. The Feds announcement of plans to reduce its bond-buying stimulus could come as soon as Wednesday, after its September policy meeting.

The Feds challenge is to carry this off at this delicate moment without provoking an economic slowdown or a selloff in stocks and bonds.

Why has the Fed kept interest rates near zero for so long? asks Bank of America Merrill Lynch co-chief economist Ethan Harris. Weve had an earnings boom, but economic growth has been slow compared to earnings.

Twice before, in 2010 and 2011, the Fed has tried to cut back on stimulus, only to see stocks and the economy shudder. Both times, it was obliged to pump fresh money into financial markets. After the Fed pared stimulus in March 2010, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 14% between April and July. In 2011, the Dow dropped 17%, with part of the decline coming in anticipation of the Fed move. Each time, the market recovered only after the Fed sent signals that it would resume stimulus.

Now, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke believes markets and the economy have recovered enough to accept a letup in Fed aid, which he plans to execute very gradually. But the evidence of a recovery isnt overwhelming. The economy has grown only about 2% a year on average since the recession ended in 2009, Mr. Harris says. Corporate profits have grown 12.7% a year, but that rate has dropped to just 2.1% over the past four quarters.

Corporate profit-growth topped out in a similar way in 2005, before the 2007 stock peak. Today, corporate profits represent 12% of gross domestic profit, the highest level since 1950, Mr. Harris says. It would be exceptional for profits share of GDP to move much higher.

Some of the recent stock selling in August and early September reflects a view that stocks are no longer cheap. The Dow is up 135% from its 2009 low and the Nasdaq Composite Index is up 193% in the same period. Some people have sold to lock in gains.

One way to gauge whether stock prices are high is to measure them in terms of corporate earnings. A widely followed price-earnings ratio is calculated by Yale economics professor Robert Shiller, using a 10-year average of corporate earnings. It shows the S&P 500 index at 24 times earnings, well above the long-term average of about 16, but still below the 2007 high of 27.

Conventional p/e ratios tracked by Birinyi Associates show the S&P 500 at about 16 times the previous 12-months earnings, below the 17.5 level of 2007.

More worrisome are some gauges tracked by Ned Davis Research. One shows margin debt in brokerage accounts, a measure of the use of borrowed money by investors, is back to levels seen at the 2000 and 2007 peaks. That worries some analysts since it suggests riskier investment are back to the extreme that preceded declines in the past. Another shows cash in money-market accounts down near lows of 2006 and 2007, as a percentage of market value. That suggests investors have less cash available to move into stocks.

Perhaps the biggest positive for markets is that the Fed has far more flexibility today than before the crisis, because inflation is subdued. In early 2006, as the housing bubble popped, the Fed was still raising short-term interest rates to fight inflation. It didnt begin cutting rates until June 2007, when mortgage-backed bonds already were in turmoil.

Today, low inflation lets the Fed promise to hold short-term interest rates near zero for months to come. Its current plans to cut stimulus involve only its bond-buying program, not any direct

changes in its target interest rates. And it even could resume the bond-buying if the economy stumbles.

Fed policy is vastly different today. It is still treating the financial system as if it is a patient returning from a near-death experience, says Merrills Mr. Harris. All of this is possible because we dont have an inflation problem, so the Fed can do a gentle exit.

Another positive sign is the passage of market leadership to rejuvenated technology stocks from the stocks of financial companies that still havent fully recovered from the battering of the financial crisis. At the 2007 stock peak, financial stocks represented more than 20% of total market value. Today, although they have rebounded, they account for about 17% while technology represents around 18%, according to Birinyi Associates. Markets tend to do better when dynamic sectors are dominant.

In 2007, the bond market was sending warning signals. Long-term interest rates were lower than short-term rates, signaling fears of economic weakness. Today, long-term rates are rising and the bond market is signaling the opposite.

The stock markets problem today is that it has already come a long way. Further gains depend on the Fed continuing to succeed and the world avoiding blowups in Asia, Europe and the Middle East. None of that is guaranteed. But so far, although stocks sank in August, trading volumes were low and selling was far from panicky. The Dow is only 1.8% off its record.

It is a tired, old advance at this point, but until there is selling pressure I wouldnt want to bet on a big decline, said Phil Roth, an independent analyst who foresaw the 2007 top.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Bonds With Warrants and Embedded OptionsDokument29 SeitenBonds With Warrants and Embedded OptionsjapanshahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISJ020Dokument81 SeitenISJ0202imediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vsa Basics From MTMDokument32 SeitenVsa Basics From MTMabanso100% (1)

- (Centre For Central Banking Studies Bank of EnglandDokument54 Seiten(Centre For Central Banking Studies Bank of Englandmalik naeemNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of The Financial System: © 2005 Pearson Education Canada IncDokument12 SeitenAn Overview of The Financial System: © 2005 Pearson Education Canada IncYasser AlmishalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar 11. Saxo PDFDokument26 SeitenSeminar 11. Saxo PDFTraian ChiriacNoch keine Bewertungen

- State of Microfinance in BhutanDokument45 SeitenState of Microfinance in BhutanasianingenevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blackbook With Formatting - Ridhima Achaliya B001Dokument81 SeitenBlackbook With Formatting - Ridhima Achaliya B001ridhima achaliyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic Hedging - Notes by Nassim TalebDokument51 SeitenDynamic Hedging - Notes by Nassim Talebmniags100% (1)

- 123trading BooksDokument200 Seiten123trading Booksrajesh bhosale33% (3)

- Strategic Analysis of SBIMFDokument19 SeitenStrategic Analysis of SBIMF26amitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Banking and Finance: Guy Hargreaves ACE-102Dokument38 SeitenIntroduction To Banking and Finance: Guy Hargreaves ACE-102Riri FahraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Olam AR 2011Dokument188 SeitenOlam AR 2011MidguardNoch keine Bewertungen

- On IpoDokument24 SeitenOn IpoKaran Jain100% (1)

- Lesson 1: Overview of Financial ManagementDokument33 SeitenLesson 1: Overview of Financial ManagementPhilip Denver NoromorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Derivative'sDokument19 SeitenDerivative'svahid100% (2)

- OECD - Pension Funds Investment in Infrastructure - SurveyDokument162 SeitenOECD - Pension Funds Investment in Infrastructure - SurveySeungjin EunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mini Project Stock BrokingDokument35 SeitenMini Project Stock BrokingKarumanchi VenkateshNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBA PROJECT Sharekhan Online Share TradingDokument101 SeitenMBA PROJECT Sharekhan Online Share Tradinggoyal_aashish024100% (1)

- Final IFM PresentationDokument29 SeitenFinal IFM PresentationSatheash SekarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 8 Test Bank PDFDokument21 SeitenChapter 8 Test Bank PDFCharmaine Cruz100% (1)

- Journal of International Business and EconomicsDokument10 SeitenJournal of International Business and EconomicsAysha LipiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Is Investment Opportunity Different From Trading Opportunity With Examples - Investing - Com IndiaDokument8 SeitenWhy Is Investment Opportunity Different From Trading Opportunity With Examples - Investing - Com IndiasudhakarrrrrrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idbi FortisDokument69 SeitenIdbi Fortisavnish_saraswat100% (1)

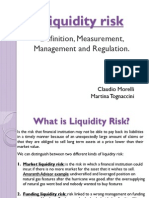

- Liquidity RiskDokument24 SeitenLiquidity RiskTing YangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karnataka Vikas Grameen BankDokument74 SeitenKarnataka Vikas Grameen Bankrangudasar0% (1)

- Glossary 2015 PDFDokument240 SeitenGlossary 2015 PDFNeelanjan BiswasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of Financial Markets and InstitutionsDokument8 SeitenRole of Financial Markets and InstitutionsTabish HyderNoch keine Bewertungen

- MB2 - The Australian Financial System PA 010615Dokument12 SeitenMB2 - The Australian Financial System PA 010615ninja980117Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hedge Funds AustraliaDokument9 SeitenHedge Funds Australiae_mike2003Noch keine Bewertungen