Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

344 Full

Hochgeladen von

Furaya FuisaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

344 Full

Hochgeladen von

Furaya FuisaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Defending commercial surrogate motherhood against Van Niekerk and Van Zyl.

H V McLachlan J Med Ethics 1997 23: 344-348

doi: 10.1136/jme.23.6.344

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/23/6/344

These include:

References Email alerting service

Article cited in:

http://jme.bmj.com/content/23/6/344#related-urls

Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To order reprints of this article go to:

http://jme.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to Journal of Medical Ethics go to:

http://jme.bmj.com/subscriptions

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Journal ofMedical Ethics 1997; 23: 344-348

Defending commercial surrogate motherhood against Van Niekerk and Van Zyl

Hugh V McLachlan Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow

Abstract

The arguments of Van Niekerk and Van Zyl that, on the grounds that it involves an inappropriate commodification and alienation of women 's labour, commercial surrogate motherhood (CSM) is morally suspect are discussed and considered to be defective. In addition, doubt is cast on the notion that CSM should be illegal.

Introduction

Van Niekerk and Van Zyl give the answer "Yes" to their following two questions. "[Is there] anything intrinsically immoral about surrogacy arrangements from the perspective of the surrogate mother herself'?"' "Is there anything intrinsic to women's reproductive labour that should keep us from commodifying it or turning it into a form of 'alienated labour'?"2 I suspect that when they say "keep us", they are not talking merely about ethical considerations which might keep them from being involved with commercial surrogate motherhood but that they have in mind legislation also affecting the rest of us. Van Niekerk and Van Zyl argue explicitly that commercial surrogate motherhood (CSM) is immoral. The impression might well be given that they present thereby implicitly a case for considering that it should be illegal. I shall suggest that their case for supposing that CSM is immoral is weak and, perhaps more importantly, that even if CSM is immoral, Van Niekerk and Van Zyl have not established that it should be illegal. The actual immorality of things is something other than the possible desirability of making them illegal.

Immorality and illegality

There is nothing intrinsically immoral about many activities which are rightly illegal. For instance, there is nothing intrinsically immoral about driving a motor car on the left side nor on the right side of a road although there are good reasons for passing

Key words

Commercial surrogate motherhood; ethics.

laws concerning such behaviour. It becomes immoral to drive on one or other side of roads when but only when there is a legally supported convention concerning which side of the road should be preferred for normal forward motion. In Scotland, although not in all other countries, it is illegal to be drunk in, to consume alcohol in, and to try to bring alcohol into stadia at which professional football matches are being played. Various and numerous people - and I am one of them - are very much in favour of the legislation. It is, they would say, by and large a very good idea to have such legislation in present-day Scotland. Football matches here are far more pleasant and safer to attend than they used to be and football supporters, when travelling to and from matches, cause less of a nuisance to other people than they used to do. Yet, there is nothing intrinsically immoral about being drunk at a football match nor drinking at a football match nor taking drink into football matches. The legislation might be poor legislation if applied in Scotland to games other than football or if applied in places other than Scotland, with different habits, conventions, attitudes and so forth. Intrinsically, however, such behaviour is no more immoral in Scotland than elsewhere, nor more immoral at football matches than at other sporting activities. It might be desirable to have a law against X even although it might not be immoral, in the absence of such a law, to do X. Even if CSM is not intrinsically immoral, there might be a good case for making it illegal. Even if CSM is immoral, there might be a good case for refraining from making it illegal. It might be undesirable to have a law against X even if, even in the absence of such a law, X is immoral. There are costs and consequences of passing, having and trying to enforce legislation. These costs and consequences are sometimes not worth bearing. They are often unpredicted and unintended. It would be a mistake to assume that the effect of illegalising X will necessarily be to make occurrences of X less frequent. For instance, did prohibition make drinking and drunkenness less common in America? Perhaps not. What it did do, by creating a black market for the production and consumption of

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Hugh VMcLachlan 345

alcohol, was to make the production and consumption of alcohol very profitable and very attractive to criminals. Organised crime was given a huge boost, the results of which still reverberate in American society. Often, more often I would say than not, actions which are immoral happen not to be illegal. Often too, actions which are immoral should not be illegal. Often, perhaps even usually, when we consider that a particular action is immoral, we do not thereby conclude that it should be illegal. Tony Blair recently said, or so I am told, that he considers that it is immoral to vote for the Conservative Party. I am sure that he does not think that it should be illegal to vote for the Conservative Party. I suspect that it is normally immoral (although not hugely so) to fail to use one's vote in a general election. Perhaps I am wrong but I do not think that such failure to vote should be illegal although it is illegal somewhere - in Australia I think. It is immoral for politicians to make promises which they do not have the intention and might not have the ability to keep. Should it be illegal for them to do so? I do not know. I do not think so. Suppose that I promise to meet a friend in town at 8 o'clock on a Tuesday evening. Suppose that as the arranged times approaches, I remember that Brookside is soon to come on the television and that the current story lines are particularly interesting. If I were to choose to fail to turn up in order that I could watch the programme then I would act immorally but I would not be doing anything that is, nor in my view should be, illegal.

Even if CSM is intrinsically immoral it does not follow that it should be illegal. The consequences of making CSM illegal might well be undesirable. Suppose that CSM is made illegal. CSM might still occur. What will be the consequences of illegal CSM? They might be different from the consequences of CSM as such just as, for instance, the consequences of prohibition were different from the consequences of normal, legal alcohol production, sale and consumption. Making, for instance, speeding, illegal similarly does not necessarily reduce instances of speeding but, dissimilarly, it does not produce a black market for speeding whatever other consequences it might have. Of course, the risks of creating a black market for CSM might be worth taking and, overall, it might be a good idea to make CSM illegal but all this would not follow necessarily from the fact, if it were a fact, that CSM is intrinsically immoral.

Van Niekerk and Van Zyl on CSM

Van Niekerk and Van Zyl argue that: "The problem with surrogacy arrangements is therefore that it causes a woman to be pregnant while expecting her not to acknowledge the fact that she is expecting her child. It tries to divorce pregnancy from the conscious knowledge that you are going to give birth to your child. In this way the surrogate becomes a mere 'environment' or 'human incubator' for someone else's child". 3 Their argument is based on the acceptance of the views on commercial surrogate motherhood of Elizabeth Anderson. They write: ". . . Anderson's point is not that surrogacy is immoral because it is a form of alienated labour, but because pregnancy should not become an act of alienated labour. Being denied the legitimacy of one's perspective on one's labour, being alienated from your feelings and having to act against one's emotions is not wrong per se, but only wrong if the labour in question is women's reproductive labour (or another special form of labour). It is in this sense that surrogacy is similar to prostitution: not that both are forms of alienated labour, but that in both cases a physical capacity (sexual intercourse and gestation) that should be afforded special respect is degraded to a form of alienated labour. What lies at the heart of the objection that surrogacy is similar to prostitution, is that women's reproductive labour, like their sexuality, should not be compared to and treated in the same way as other forms of physical labour. Anderson says that '[p]regnancy is not simply a biological process but also a social practice. Many social expectations and considerations surround women's gestational labour, marking it off as an occasion for the parents

The Ten Commandments

Consider the Ten Commandments. In, for instance, Britain, how many of the ten explicitly or implicitly proscribed actions are illegal? Not many of them. How many of them do you think are immoral? How many of them do you think should be illegal? I think that, as a general thing, it is morally wrong, for instance, to bear false witness against your neighbour, to fail to honour your father and mother and to commit adultery. However, I am not thereby logically committed to the view that these actions should be illegal. I think that they should not be illegal. Certain sorts of false witnessing against one's neighbour, for instance, perjury and some libels and slanders should be illegal but not false witness as such. It is morally wrong, say, to say, when he did not, that your neighbour voted Labour but it should not be illegal to do so. One's attitude to one's parents is a matter which the state neither can nor should legislate about. In Scotland, adultery used to be a crime: it used, in fact, to be a capital offence. I do not think that adultery should be a criminal offence nowadays: I am certain that it should not be a capital offence.

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

346 Defending commercial surrogate motherhood against Van Niekerk and Van Zyl

to prepare themselves to welcome a new life into their family"'. 2

Once you become, say, married, you cannot always regard your own body and your own life in the same way you could when you were single. When you voluntarily become pregnant you cannot always regard your own body and your own life in the same way that you could before you were pregnant. If you become party to a contract pregnancy, then you cannot always regard your body and your pregnancy in the same way that you could if you did not involve yourself in such an arrangement. You might change your mind after you have agreed to part with the baby: your feelings about the CSM agreement might develop contrary to your own predictions concerning them. All this is true enough but it does not seem a reason for disfavouring such contractual and quasicontractual arrangements: it is, rather, a sort of description of them and, perhaps, a warning against entering into them too lightly. I am not convinced that commercial surrogate motherhood "commodifies" people nor necessarily, say, undermines the moral autonomy proper to women nor the dignity and respect due to them. To treat reproductive labour as if it were a mere commodity would, no doubt, be to "degrade" it but it is far from clear that CSM need involve treating the reproductive labour, far less the "labourer", as a mere commodity.

because of this possibility and nor do we have reason thereby for saying that commercial surrogate motherhood is immoral. Van Nierkerk and Van Zyl argue that there is something in particular about commercial surrogate motherhood that renders it - unlike otherwise similar contractual arrangements - immoral but their argument is weak. They say that the problem with commercial surrogate motherhood is that ". . . the surrogate becomes a mere 'environment' or 'human incubator' for someone else's child".3

Social meaning

The surrogate mother "becomes" no such thing. In some respects she - or, rather, her body - is, or is like an "environment" and a "human incubator" (as is, in some respects, any potential mother's body). What is immoral about that? In other respects, given that she is a human being, she is quite unlike an inanimate environment or incubator. She never is and never could become a mere "environment" nor a mere "human incubator". Van Niekerk and Van Zyl stress that there is a "social meaning" to pregnancy. They say: "As we have indicated above, the distinguishing feature of human pregnancies is that they may also entail a conscious knowledge of the significance of this physiological state and an active expectation of, and preparation for, the birth of a child. Although it is hardly 'natural' or 'normal' for a person to develop this kind of perspective on her (or his) pregnancy, we can all recognise that it is good. Yet contract pregnancies are geared towards keeping the surrogate from experiencing pregnancy and childbirth in this way. Instead, it asks the surrogate to relinquish her ability to interpret and control the meaning or significance of her reproductive labour".4

Different contexts

People can have a cluster of attitudes towards the same thing or activity: they can value the same thing or activity differently in different contexts; they can value the same thing in similar contexts in different ways. If people pay a woman for her services in, say, carrying a fetus they are, in some respects, treating the service as a "commodified" one but it does not follow that they are necessarily treating it merely as that and it certainly does not follow that they need consider the surrogate mother or the carried child as being - any more than other mothers and other children - commodities. We might pay a taxi-driver to convey a heavy trunk, a mother and a child from one part of town to another: is this necessarily to treat a woman and/or a baby as if it were a trunk or a trunk as if it were a human being? Is it to treat the taxi driver as if she were a mere commodity or a mere aspect of a commodified service? It is possible - though I doubt whether it commonly happens that some people might have a problem in distinguishing between and appreciating the significance of the difference between the commodified service of surrogate motherhood and the non-commodifiable person who provides it but that, I would suggest, is a problem about and for those particular people: we do not require the state to intervene and pass laws against commercial surrogate motherhood merely

Why need there be only one interpretation of one's pregnancy which is appropriate? Might there not be, in particular, feelings, interpretations and meanings appropriate to commercial surrogate motherhood which are different from those appropriate to other pregnancies? Obviously, if someone agrees to become a commercial surrogate mother then she is not "free" to imagine that she has not become a commercial surrogate mother nor "free" to interpret her pregnancy as the pregnancy of a non-surrogate mother. Such is the nature of contracts. That is a reason why such arrangements should be undertaken thoughtfully: it is not a reason for thinking that CSM is immoral nor for wanting to ban it. To make CSM illegal would be to prohibit mothers from making other particular interpretations of their pregnancy which they might (and sometimes do) want to make. Van Niekerk and Van Zyl write:

"Thus, instead of saying that reproductive labour is

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

Hugh VMcLachlan 347 the most integral part of the female identity (as Pateman does), one can rather claim that the bond between a pregnant woman and her child is usually (or should be) an integral part of her pregnancy".3

In the case of commercial surrogate motherhood, perhaps such a bond is not and should not be integral to the pregnancy. Van Niekerk and Van Zyl write:

"Because surrogacy arrangements by definition involve more than two people, all of whom can legitimately claim that s/he is the parent of the child, a conflict can in principle always arise about who should assume parental rights and responsibilities towards the child. It seems that this is a problem inherent to surrogacy arrangements, since one can never be certain that such a conflict will not arise. It is easy to praise a successful arrangement in retrospect, but the danger always exists that an arrangement one is planning would cause moral harm to the surrogate and/or the commissioning parents.... Unless one can ensure the legitimacy of the surrogate's bond with the child and her perspective on her pregnancy without thereby denying that of the commissioning couple, the surrogacy arrangement can always be said to be dehumanising or alienating".5

for the moral goodness concerned. There is no sole criterion of, say, games, knowledge or moral goodness and, even it it turns out that there is, logically, there need not be. The same applies, I think, when "X" stands for those particular actions which should be illegal: there are various factors which can count against the desirability of making particular actions illegal and various factors which can weigh in the other direction. For instance, it can count in favour of making some actions illegal that, even if they have negligible - if any - harmful social consequences, they are inherently not only wrong but very wrong because, say, of the reasons for which they were done and/or the spirit in which they were done. It can count in favour of making some actions illegal, whether or not they are morally wrong in themselves that they are very socially harmful. Sometimes, even when some particular actions are morally wrong and/or are socially harmful, it is wise not to make them illegal because of the overall consequences - and by "consequences" here, I have in mind not merely the amount of happiness and harm produced but the distribution of it - of the illegality, which are something other than the consequences of the actions in

question. For instance too, it can count against the advisability of making an action a crime that the resulting law cannot be or will not be enforced and that deviOne might say that it is easy to praise, for instance, a ations from the resulting law cannot or will not be successful marriage in retrospect, but it is always appropriately punished. Sometimes, the effects of possible that it could have produced misery for the the non-enforcement of particular legislation, husband and/or the wife and/or the children of the including resultant disrespect for other potentially marriage. So what? Is marriage inherently problem- more readily enforceable legislation, is such that its atical and alienating and intrinsically likely to lead to non-existence would be preferable even when the conflicts? Even if it is, so what? Would marriage law would be a very good law were it to be enforced. thereby necessarily be immoral? Whether or not I suspect that much traffic legislation comes into this marriage is inherently problematical in any way category. Perhaps the scarcely enforced and littleand/or immoral, does it follow that it would be a regarded British speed limits should be abolished: good idea to make marriage illegal? Surely not! they could be replaced by recommendations and dangerous and reckless speeding could be prosecuted as dangerous or reckless driving. Yet, the comConclusion plication arises that even when a law is a bad one in I accept the Wittgenstein-inspired notion that those the sense that it would have been better not to have things which are "Xs" - for instance, games - must formulated it in the first place, its repeal, after it has possess some or other of the defining features of Xs been long established, can have bad consequences. but that these features need not be common to all Perhaps the repeal now of the speeding legislation Xs. There is a middle ground between nominalism would lead some people to drive more dangerously and essentialism.6 I think that the theory is applic- than they now do in the erroneous belief that vehicle able to all general terms. It applies to terms like speed was no longer of legal or ethical importance. "knowledge" and "moral goodness" no less than to Legislation is, indeed, a messy business. When, precisely, in general, something is immoral less interesting ones such as games. The features by virtue of which things are, say, known to be true or and when, precisely, in general, something should be are morally good need not be the same in all illegal, I make no pretence to know. Perhaps CSM is instances of knowledge nor the same in all instances immoral. Perhaps, whether or not it is immoral, it of moral goodness. Perhaps, for instance, utilitarian- should be illegal. I do not think that it is immoral ism accounts correctly for the moral wrongness of and nor do I think that it should be illegal. That it some actions and, say, Kantianism correctly should be legal and that it is not immoral is my accounts for the moral goodness of others. There firmly held view. Nothing which Van Niekerk and might be other morally good actions where neither Van Zyl say in the article of theirs which I have disutilitarianism nor Kantianism can correctly account cussed constitutes a reason for slackening my view.

Downloaded from jme.bmj.com on September 13, 2010 - Published by group.bmj.com

348 Defending commercial surrogate motherhood against Van Niekerk and Van Zyl

Van Niekerk and Van Zyl are undoubtedly correct in maintaining that commercial surrogate motherhood can, like many things in life (including normal motherhood), lead to problems and personal distress: people are taking a risk and might well be acting unwisely when they get involved, in any capacity, with surrogate motherhood. What they do not demonstrate is that surrogate motherhood is immoral nor that it should be illegal: that any of the parties involved are doing something which they ought not to do and/or should not be legally entitled to do. Van Niekerk and Van Zyl leave wide open both the independent questions of whether or not CSM is immoral and of whether or not it should be illegal.

Hugh VMcLachlan, MA, PhD, is Lecturer in Sociology in the Department of Social Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow.

References

1 Van Niekerk A, Van Zyl L. The ethics of surrogacy: women's reproductive labour. J'ournal of Medical Ethics 1995; 21: 345. 2 See reference 1: 346. 3 See reference 1: 347. 4 See reference 1: 348. 5 See reference 1: 348-9. 6 McLachlan HV. Wittgenstein, family resemblances and the theory of classification. International J7ournal of Sociology and Social Policy 1981; 1,1: 1-16.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Fixing This Broken Thing...The American Criminal Justice SystemVon EverandFixing This Broken Thing...The American Criminal Justice SystemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Regulation Out of Hand?Dokument10 SeitenIs Regulation Out of Hand?NCVONoch keine Bewertungen

- ProstitutionDokument5 SeitenProstitutionThomas Anthony MarceloNoch keine Bewertungen

- DebateDokument4 SeitenDebateGenelle SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Male Prostitution Research PaperDokument7 SeitenMale Prostitution Research Papermwjhkmrif100% (1)

- The Legalization of ProstitutionDokument6 SeitenThe Legalization of Prostitutionapi-242815652Noch keine Bewertungen

- Libertarianism V AuthoritarianismDokument2 SeitenLibertarianism V Authoritarianismmatthew WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Previous Year Oxford Interview QuestionsDokument12 SeitenLaw Previous Year Oxford Interview QuestionspvbadhranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Statements in Legal ResearchDokument11 SeitenThesis Statements in Legal ResearchNadya Vera SimanjuntakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Term Paper ProstitutionDokument7 SeitenTerm Paper Prostitutionafmzxutkxdkdam100% (1)

- Nudity and The Law in Washington StateDokument11 SeitenNudity and The Law in Washington StateRick100% (3)

- Marriage Equality SubDokument3 SeitenMarriage Equality SubSam HumphreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is An AsboDokument5 SeitenWhat Is An AsboTrân MoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prostitution and EthicsDokument13 SeitenProstitution and EthicshaleyloiaconoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fallacy of Weak InductionDokument5 SeitenFallacy of Weak InductionStephen Bueno100% (1)

- Policy Considerations For SurrogacyDokument22 SeitenPolicy Considerations For SurrogacySatyajeet ManeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper Outline For ProstitutionDokument8 SeitenResearch Paper Outline For Prostitutionafmcgebln100% (1)

- Peter Suber - PaternalismDokument4 SeitenPeter Suber - PaternalismNiCk FirDausNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper About ProstitutionDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper About Prostitutionqxiarzznd100% (1)

- Prostitution Thesis PaperDokument8 SeitenProstitution Thesis PaperSteven Wallach100% (2)

- Why Prostitution Should Not Be LegalizedDokument3 SeitenWhy Prostitution Should Not Be LegalizedDanny SimonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Statement Against Legalizing ProstitutionDokument6 SeitenThesis Statement Against Legalizing ProstitutionWriteMyApaPaperBatonRouge100% (1)

- JurisprudenceDokument2 SeitenJurisprudenceVictory Eniola MatthewNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of The Criminal Defence LawyerDokument5 SeitenThe Role of The Criminal Defence LawyerSebastián MooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On Abortion OutlineDokument7 SeitenResearch Paper On Abortion Outlinenaneguf0nuz3100% (1)

- Dear Fellow Intactivists - Let It Be Known - There Are Intactivist Actions Which Make GOOD SENSE, and There Are Actions Which Do Not Make Sense at All, BUT Are Even Counterproductive.Dokument3 SeitenDear Fellow Intactivists - Let It Be Known - There Are Intactivist Actions Which Make GOOD SENSE, and There Are Actions Which Do Not Make Sense at All, BUT Are Even Counterproductive.Amen Ronald OberhollenzerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prostitution Debate Closing StatementDokument4 SeitenProstitution Debate Closing Statementapi-425380114Noch keine Bewertungen

- Example of Thesis About ProstitutionDokument7 SeitenExample of Thesis About Prostitutiondianamarquezalbuquerque100% (2)

- Persuasive Thesis Statement Against AbortionDokument7 SeitenPersuasive Thesis Statement Against AbortionHelpWithAPaperMiamiGardens100% (2)

- Sample Thesis About ProstitutionDokument8 SeitenSample Thesis About Prostitutiondonnacastrotopeka100% (2)

- Buying & Selling of A Minor For ProstitutionDokument31 SeitenBuying & Selling of A Minor For ProstitutionSadiq Noor100% (1)

- Why Gay Rights Judgment Is WrongDokument7 SeitenWhy Gay Rights Judgment Is WrongSatish MurthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of Prostitution Research PaperDokument8 SeitenConcept of Prostitution Research Papereh041zef100% (1)

- White Collar Crime Survey 2019Dokument48 SeitenWhite Collar Crime Survey 2019Shaikh NavedNoch keine Bewertungen

- BF 03351151Dokument12 SeitenBF 03351151JESSICA GONZALEZ MENDEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 1Dokument8 SeitenAssignment 1Sande DotyeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prostitution Essay Research PaperDokument6 SeitenProstitution Essay Research Papernidokyjynuv2100% (1)

- Example of Term Paper About ProstitutionDokument4 SeitenExample of Term Paper About Prostitutionafmzksqjomfyej100% (1)

- Duty To RescueDokument7 SeitenDuty To RescueIbrahim WagdyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right To Travel Via AutomobileDokument306 SeitenRight To Travel Via AutomobileChristian Bikle89% (18)

- Thesis Paper About RH BillDokument6 SeitenThesis Paper About RH BillWriteMyNursingPaperCanada100% (2)

- A Study On Deeds That Are Legal But UnethicalDokument7 SeitenA Study On Deeds That Are Legal But UnethicalJashim UddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- History and Debate of Legalized ProstitutionDokument6 SeitenHistory and Debate of Legalized ProstitutionAisya FikritamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reply To Anderson and McDougallDokument6 SeitenReply To Anderson and McDougalljazzy075Noch keine Bewertungen

- White Collar Crime Research Paper TopicsDokument7 SeitenWhite Collar Crime Research Paper Topicsgw131ads100% (1)

- Thesis Statement About ProstitutionDokument4 SeitenThesis Statement About Prostitutionallysonthompsonboston100% (2)

- The Great Final Report 2011 PDF DownloadDokument151 SeitenThe Great Final Report 2011 PDF Downloadscullen71869Noch keine Bewertungen

- Running Head: ETHICS 1Dokument5 SeitenRunning Head: ETHICS 1700143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis About ProstitutionDokument5 SeitenThesis About ProstitutionKayla Smith100% (2)

- Speaking of ProstitutionDokument64 SeitenSpeaking of ProstitutionBego VeganEdgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Reading SpeechDokument3 SeitenSecond Reading SpeechPolitical AlertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper - ProstitutionDokument4 SeitenResearch Paper - Prostitutionchanwing100% (1)

- The Street-Law Handbook: Surviving Sex, Drugs, and Petty CrimeVon EverandThe Street-Law Handbook: Surviving Sex, Drugs, and Petty CrimeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (4)

- Sample of Research Paper About ProstitutionDokument7 SeitenSample of Research Paper About Prostitutioncaqllprhf100% (1)

- 20200408-Press Release MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. Issue - Re Constitutional Quarantine Powers, EtcDokument4 Seiten20200408-Press Release MR G. H. Schorel-Hlavka O.W.B. Issue - Re Constitutional Quarantine Powers, EtcGerrit Hendrik Schorel-HlavkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- From The StarDokument3 SeitenFrom The StarJuan DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patrick Devlin, Morals and The Criminal LawDokument9 SeitenPatrick Devlin, Morals and The Criminal LawRikem KM100% (1)

- Thesis Statement On Against AbortionDokument4 SeitenThesis Statement On Against AbortionBestPaperWritersUK100% (2)

- 320 FullDokument4 Seiten320 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jclinpath00256 0014 PDFDokument5 SeitenJclinpath00256 0014 PDFFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 404 FullDokument7 Seiten404 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 605 FullDokument6 Seiten605 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 345 FullDokument6 Seiten345 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Donate Your Body: The Role of The HTA in Body DonationDokument15 SeitenHow To Donate Your Body: The Role of The HTA in Body DonationFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stemcell From KadaverDokument5 SeitenStemcell From KadaverFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 164 1 FullDokument2 Seiten164 1 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 230 FullDokument5 Seiten230 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 61 FullDokument6 Seiten61 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Or Public Wrong? Surrogate Mothers: Private Right: Doi: 10.1136/jme.7.3.153Dokument3 SeitenOr Public Wrong? Surrogate Mothers: Private Right: Doi: 10.1136/jme.7.3.153Furaya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 53 FullDokument5 Seiten53 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 171 FullDokument6 Seiten171 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABN Biorepository Protocols - Revision 4Dokument85 SeitenABN Biorepository Protocols - Revision 4Furaya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 64 FullDokument4 Seiten64 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 35 FullDokument9 Seiten35 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abortion Decisions As Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Involving Pregnant Women and FetusesDokument6 SeitenAbortion Decisions As Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Involving Pregnant Women and FetusesFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- When Should Conscientious Objection Be Accepted?: Morten MagelssenDokument5 SeitenWhen Should Conscientious Objection Be Accepted?: Morten MagelssenFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Clear Case For Conscience in Healthcare Practice: Giles BirchleyDokument6 SeitenA Clear Case For Conscience in Healthcare Practice: Giles BirchleyFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privacy, Confidentiality and Abortion Statistics: A Question of Public Interest?Dokument5 SeitenPrivacy, Confidentiality and Abortion Statistics: A Question of Public Interest?Furaya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 60 FullDokument5 Seiten60 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnostic Misconceptions? A Closer Look at Clinical Research On Alzheimer's DiseaseDokument4 SeitenDiagnostic Misconceptions? A Closer Look at Clinical Research On Alzheimer's DiseaseFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 26 FullDokument6 Seiten26 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 35 FullDokument9 Seiten35 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 48 FullDokument6 Seiten48 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abortion Decisions As Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Involving Pregnant Women and FetusesDokument6 SeitenAbortion Decisions As Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria in Research Involving Pregnant Women and FetusesFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 35 FullDokument9 Seiten35 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 26 FullDokument6 Seiten26 FullFuraya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Privacy, Confidentiality and Abortion Statistics: A Question of Public Interest?Dokument5 SeitenPrivacy, Confidentiality and Abortion Statistics: A Question of Public Interest?Furaya FuisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ingles Junio 17 CanariasDokument5 SeitenIngles Junio 17 CanariaskinkirevolutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenueDokument4 SeitenCase Study For Southwestern University Food Service RevenuekngsniperNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief Introduction of The OperaDokument3 SeitenA Brief Introduction of The OperaYawen DengNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOW OutlineDokument3 SeitenSOW Outlineapi-3697776100% (1)

- Estimating Guideline: A) Clearing & GrubbingDokument23 SeitenEstimating Guideline: A) Clearing & GrubbingFreedom Love NabalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judgments of Adminstrative LawDokument22 SeitenJudgments of Adminstrative Lawpunit gaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- LSG Statement of Support For Pride Week 2013Dokument2 SeitenLSG Statement of Support For Pride Week 2013Jelorie GallegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept Note TemplateDokument2 SeitenConcept Note TemplateDHYANA_1376% (17)

- Enochian Tablets ComparedDokument23 SeitenEnochian Tablets ComparedAnonymous FmnWvIDj100% (7)

- Edu 414-1Dokument30 SeitenEdu 414-1ibrahim talhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cult of Shakespeare (Frank E. Halliday, 1960)Dokument257 SeitenThe Cult of Shakespeare (Frank E. Halliday, 1960)Wascawwy WabbitNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Atlas Including Geography Facts, Maps, Flags - World AtlasDokument115 SeitenWorld Atlas Including Geography Facts, Maps, Flags - World AtlasSaket Bansal100% (5)

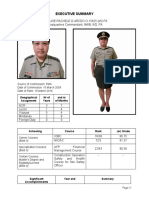

- Executive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Dokument3 SeitenExecutive Summary: Source of Commission: PMA Date of Commission: 16 March 2009 Date of Rank: 16 March 2016Yanna PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecology Block Wall CollapseDokument14 SeitenEcology Block Wall CollapseMahbub KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart Notes Acca f6 2015 (35 Pages)Dokument38 SeitenSmart Notes Acca f6 2015 (35 Pages)SrabonBarua100% (2)

- Option Valuation and Dividend Payments F-1523Dokument11 SeitenOption Valuation and Dividend Payments F-1523Nguyen Quoc TuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sbi Rural PubDokument6 SeitenSbi Rural PubAafrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Item 97952Dokument18 SeitenBook Item 97952Shairah May MendezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The State of Iowa Resists Anna Richter Motion To Expunge Search Warrant and Review Evidence in ChambersDokument259 SeitenThe State of Iowa Resists Anna Richter Motion To Expunge Search Warrant and Review Evidence in ChambersthesacnewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFDokument3 Seiten78 Complaint Annulment of Documents PDFjd fang-asanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Paid Search Advertising - TranscriptDokument4 SeitenIntroduction To Paid Search Advertising - TranscriptAnudeep KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Logistics Specialist NAVEDTRA 15004BDokument970 SeitenLogistics Specialist NAVEDTRA 15004Blil_ebb100% (5)

- Discipline, Number of Vacancies, Educational Qualification and ExperienceDokument8 SeitenDiscipline, Number of Vacancies, Educational Qualification and ExperienceMohammedBujairNoch keine Bewertungen

- SWOT Analysis and Competion of Mangola Soft DrinkDokument2 SeitenSWOT Analysis and Competion of Mangola Soft DrinkMd. Saiful HoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening Practice9 GGBFDokument10 SeitenListening Practice9 GGBFDtn NgaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssignmentDokument25 SeitenAssignmentPrashan Shaalin FernandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.jjeb.g.p 2019Dokument4 SeitenA.jjeb.g.p 2019angellajordan123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Carl Rogers Written ReportsDokument3 SeitenCarl Rogers Written Reportskyla elpedangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anderson v. Eighth Judicial District Court - OpinionDokument8 SeitenAnderson v. Eighth Judicial District Court - OpinioniX i0Noch keine Bewertungen

- StarbucksDokument19 SeitenStarbucksPraveen KumarNoch keine Bewertungen