Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Teachers Development

Hochgeladen von

Antonio M GladinOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Teachers Development

Hochgeladen von

Antonio M GladinCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [187.244.165.

6] On: 17 January 2013, At: 20:06 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Teacher Development: An international journal of teachers' professional development

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtde20

The professional formation of teachers: a case study in reconceptualising initial teacher education through an evolving model of partnership in training and learning

M. Totterdell & D. Lambert

a a a

Institute of Education, University of London, United Kingdom Version of record first published: 20 Dec 2006.

To cite this article: M. Totterdell & D. Lambert (1998): The professional formation of teachers: a case study in reconceptualising initial teacher education through an evolving model of partnership in training and learning, Teacher Development: An international journal of teachers' professional development, 2:3, 351-371 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13664539800200066

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION Teacher Development, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1998

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

The Professional Formation of Teachers: a case study in reconceptualising initial teacher education through an evolving model of partnership in training and learning

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT Institute of Education, University of London, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT The initial training and education of teachers in England has been subject to enormous political interest in recent years, resulting in radical change imposed from the centre. This article offers a case study of how one large postgraduate course in London has responded, although the authors also maintain that reform was already beginning to take place from within. External forces have changed structures, but what is perceived also to be happening is a fundamental change in the ways we (as educators) think and talk about teacher education. The authors identify six key problematics within an evolving partnership model of training which, they argue, mark out a range of complex issues rich in implication both for educational practice and for future course development. They conclude by arguing that such a long overdue reconceptualisation of the Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) is an essential prerequisite of the more effective advocacy of a broad-based teacher education as opposed to a narrower view of training in operational competence.

Introduction The purpose of this article is to set out a deep description of one large postgraduate initial teacher education programme, namely the secondary Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) at the University of London Institute of Education (ULIE). It is in effect a case study in reconceptualisation of the initial training project in that our main aim is to show how continuing concerns about how the PGCE course is structured have now been subsumed by bigger and more difficult questions concerning the ways in which higher education (HE) tutors, teachers and beginning teachers conceptualise initial teacher education and training. We believe that teacher education is, perhaps belatedly, beginning to benefit from rigorous

351

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

challenge and re-examination. This article claims to make a modest contribution to that process. Initial Training: a question of structure or of concept? The ULIE began to move to a new configuration for initial teacher education (ITE) in the early 1990s, following staff conferences and experimental work which demonstrated ever more clearly the inadequacies of the then existing arrangements (broadly, a model of learning-to-teach based upon the university providing the knowledge, methods and skills, the schools providing the setting for practice and the beginning teachers supplying the individual effort to integrate and apply such training). At the same time, internal discussions began to render the then de rigeur principle of reflective practice problematical, challenging what had become a dangerously empty slogan, a hostage to fortune in an increasingly aggressive world of performativity (Ball, 1994). The obstacle to root and branch change, and the achievement of a less constrained way of thinking about such matters, was considered by many to be essentially structural. For example, debates encompassed among other things: x the dominance of quasi-autonomous curriculum departments and method tutors in course design and implementation; x the poor relation status of professional studies, often taught by part-time staff bought in on an ad hoc basis and somehow strangely rootless. The so-called educational issues course component had replaced lecture and seminar courses on the foundation disciplines but despite rhetoric asserting its student-centred and enquiry-based methodology, the component was for many a content-packed, handout-driven seminar course of limited applicability; x teaching practice being seen by ULIE, schools and students alike as something separate from the rest of the course and by many as the only component that really mattered. ULIE deliberations resulted in the so-called Area Based course (Harland, 1992), which was an attempt to devise a structure which would permit and encourage certain ways of working. By organising clusters of schools working with groups of beginning teachers, each with a seconded general tutor supporting beginning teachers both inside the schools and at the ULIE on a professional studies programme (one cluster of 3-4 schools contained one tutor group of 17-23 mixed-subject beginning teachers), a structure was designed which enabled partnership in training the clusters providing the context for experience-based learning. It was soon clear that structural change of this kind cannot, on its own, bring about a resolution of tensions such as those noted earlier and which student evaluations had consistently revealed to be present. It is possible that the reformation of the PGCE had not been radical enough, but the autonomy of the curriculum departments remained (perhaps reinforced by the

352

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

subject-based National Curriculum), student evaluations tending to describe the PGCE course as one consisting of, in at least two senses, separate worlds. Beginning teachers recognised first, the continued discontinuity between curriculum and professional studies components of the course and secondly, the stubborn persistence of the schoolHE divide, characterised by some as the separation of theory and practice. Crucially, however, the area based structure provided the basis for imaginative steps to be taken beyond discussions over the arrangement of predetermined course components. Increasingly, fundamental questions began to emerge in the area teams. Some tutors, for example, conservatively argued, on entitlement grounds, for beginning teachers to be exposed to (to be given) certain ideas and knowledge, which seemed to others tantamount to handing students a canon of literature a tendentious view of postgraduate training. Such critics likened any such move to a literary canon as a step back to discredited models of delivering the foundation disciplines; what initial trainees needed, they argued, was not a cumulative, informational entitlement but access to ways of working and approaches to learning to enable understanding and competence to develop. In this way, debates had begun to move from considerations of structure to reconceptualising ITE and training. Deliberations such as these began to take shape shortly before radical change was instigated from the centre (Department for Education [DfE], 1992; see Wilkin & Sankey, 1994), forcing all PGCE courses to negotiate quasi-contractual partnership structures in which student teachers would spend around two-thirds of their time in schools and instituting a national framework for standards of teaching competence which is subject to accreditation and inspection. As a result, colleagues felt less reactive than perhaps otherwise they may have done, and more responsive to the possibilities of courses recontextualised and reinterpreted under the new regulations. However, the course leaders were also acutely aware that the new, centrally imposed structure of partnership needed to be conceptualised, and the collective thinking that had already been achieved concerning collaboration with schools not only helped guide the adaptation of the course to the new conditions (at the time Circular 9/92, now superseded by Circular 4/98), but served to inaugurate a much more fundamental reconceptualisation than anything previously envisaged. For example, the course leadership was prepared to pursue further basic questions concerning: x the fundamental aims of ITE and the images we hold of what it is to be a teacher; x the ways in which we wanted beginning teachers to work and engage with schools, practising teachers and children; x the manner in which we wished to specify the particular contribution of the HE side of partnership in training and learning [1]; and x the manner in which we wanted to recognise the postgraduate status of our beginning teachers (and the kinds of expectations we could legitimately place on them).

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

353

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

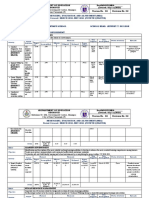

In short, the ULIE team had begun to remodel the PGCE in a way which is summarised rather neatly (though simplistically) by the ITE curriculum cube (Lambert & Totterdell, 1995, reproduced in Figure 1). The idea that the PGCE can be reconceptualised as a curriculum certainly has an ironic ring to it. But it enables a move away from course components (slots to be filled) and closer to a concept of a dynamic and organic whole. This provides a number of avenues for development and the sense of a course (and a course team) being in charge of its own destiny, taking ownership of the quality of the whole course experience of beginning teachers, and being on a forward-facing trajectory but with an increasingly sophisticated understanding of weaknesses and ambiguities present in the whole project not least in how teacher training matters tend to be articulated (see Wilkin, 1996). For example, what does partnership in training and learning claim to achieve? In what ways is the HE side valued and valuable? In what ways are schools the best places for beginning teachers to learn, and what do they tend to achieve less well in the school setting? What do we expect beginning teachers to learn and how are they best supported? In what ways might the training and learning partnership per se act as a catalyst for raising standards in schools to the overall benefit of education in London? (see Collarbone & MacGilchrist, 1996).

100mm

Figure 1. The PGCE curriculum cube.

354

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

The PGCE curriculum is contained inside the box. Choose any one of the three sides as a way into the box and you cut across other concerns. For example, choosing the aspect of the Teacher as Reflective Professional means we must engage with curriculum studies, professional studies and practical teaching. Furthermore, reflective activity will at different times be linked with highly practical and immediate concerns, the wider context affecting teaching and learning and future personal and professional development (source: Lambert & Totterdell, 1995, p. 19). Conceptualising Partnership in Training and Learning Developing an approach to partnership in training and learning, being seen primarily as a conceptual problem, has provided an opportunity for the re-examination of some widely held assumptions concerning how ITE should proceed, and a stimulus for renewed and more sharply focused research activity in the field. Learning, of course, in the professional sphere, like elsewhere, is not some timeless essence. We have chosen to respond to learning as an ever-changing historical phenomenon by identifying six key problematics [2], each of which can be thought of as being contested in some way, or at least as exhibiting tensions which in themselves could be considered as an impetus for growth and a source of creative energy from which the evolving partnership in pedagogy can draw. The six problematics are identified as: x the political situatedness of initial teacher education; x a critique of reflective practice; x notions of a scholarship of teaching; x the role of experience in relation to meaning; x the role of research in the learning community; and x theory, practice and models of learning for professional formation. Each problematic is explored briefly in what follows. We do not claim that we have identified them in their entirety, nor that the ULIE PGCE has fully met the issues described. But where we feel that the ULIE course has a feature which owes its presence to the particular manner in which a problematic has been conceptualised we have attempted to make this explicit. We do not claim that the list is exhaustive. There are other dimensions, some of which may be derived from the aforementioned list, such as the empowerment of colleagues in schools; issues of consistency and comparability across the course and across schools; and reconciling (if that is the correct word) the particular and the general within the whole training experience. These constitute important quality issues with which we assume all initial training partnerships continue to grapple. Our contention is that the analysis of such issues will gain considerably from the guiding light arising from an uninhibited reworking of the conceptual landscape of teacher education. In our view such reconceptualisation is

355

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

imperative if we are to adapt to changes in learning and to equip tomorrows teachers to anticipate likely changes and challenges in the future. The Political Situatedness of ITE An Outline of the Field and Key Questions Teacher education is particularly susceptible to economic, demographic and political pressures. It is clear that these pressures are increasingly global in their configuration and will not go away (cf. Wideen, 1997). Moreover, in England, the assumptions underlying the democratic socialist welfare state have been questioned by recent governments; attempts to reconstruct teacher professionalism and make the teaching force more responsive to the demands of the evaluative state and the market are particularly evident in the attempts to reform teacher education. It is already clear that significant continuities in policy will remain even with the recent change of government (see Department for Education and Employment [DfEE], 1998). How are teacher educators to respond? One response has been for the teacher education community to become defensive, reactionary and reluctant to engage in internally-generated reform, perhaps for fear of being burdened with an ideological guilt by association syndrome, or possibly, as some critics suggest, because the culture of ITE is peculiarly resistant to change. With regard to the latter, it is said that initial training, in both content and structure, has developed a linguistic and cultural affluence which results in those involved being prone to live lives of their own; the original educational purpose is lost to view and a failure to define programme focus follows (Padgham, 1983). Yet, we do well to remind ourselves that as long ago as 1972, the James committee warned that teacher education was in danger of becoming too academic and of losing its roots in professionalism and the improvement of practice in schools (see Porter, 1997). Ever since, polemics have continued to centre on a fundamental disagreement about the priority respectively of operational competence and academic competence (Barnett, 1994), of instrumental action as against cognitive interaction. For us, this raises the question of whether it is possible to find common ground in ITE. Can there be a substantive centrist position between, on the one hand, the rearguard of academics lamenting the loss of a process model of pre-service education linked to constructivist theories of knowledge and an idealisation of the trainee teacher as transformative intellectual, and on the other hand, the vanguard of managerial educators advocating an outcomes model of competence-based professionalism, focusing on skills best learned at the chalkface? If so, it must be a pragmatic middle way movement capable of bearing the responsibility of developing an acceptable, broad and balanced approach. The challenge would be to recover common purpose and so join thought and action as to ensure that competency can fully reside in an independent professionalism capable of sustaining itself under pressure to

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

356

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

raise standards while at the same time assisting to stabilise education around a recuperated sense of positivity. The world of ITE is fast becoming functionally fragmented. To the extent that we still subscribe to Deweys dictum that there can be no intellectual growth without some reconstruction, some reworking, arguably it is time to look seriously at crafting a vigorous centrist position.[3] This would include a reappraisal of government initiatives which would set aside the rhetoric and seek to appropriate the value-added potential for trainee teachers latent within their existing form. Furthermore, it would seek to engender creative professional activity and participatory competencies which reflect a broader conception of educational citizenship particularly in terms of teachers assuming responsibility for continuously enriching and extending their craft both conceptually and practically within educational communities that foster the common good. Relocating the Debate on the Political Positioning of ITE The development of a culture in ITE that will promote collaboration between all stakeholders is imperative. The challenge is to advance an attitudinal context of trust rather than one of suspicion: to avoid polarising national agencies and educationists into communities of educational correction and resistance. We need to synthesise a complex of ideas, assumptions and principles into a more open kind of communicative exercise, responsive to the imperative to forge greater consensus around pressing questions of: x who should teach given that teaching involves the dispensation of knowledge, the cultivation of intelligence and imagination, and also that it incorporates a moral gesture? x what are the best (or better?) ways of preparing those who wish to teach given its inherent complexity derived from the need to hold together understandings of education, instruction, learning and curriculum in interaction with students? x how can their professional preparation better enable them to continue to learn and to adapt in a change rich environment to have the capacity to navigate, survive, not to be surprised, and to cope with the entirely new? (Holland, 1995, p. 2); and x how can they be imbued with a sense of vocation and with broader sensibilities a wider frame of reference and perspective drawn from the interior meanings of education with a sense of its transcendent ends? Relevant Course Framework According to Wilkin (1996), there are professional advantages to be derived from our policy-driven context. Given the current restructuring of ITE, the ULIE has worked with its school partners on so converting the curriculum as to extrude professional and pedagogic benefits from within the new

357

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

framework. Revised course documentation and a series of occasional papers have reinvigorated the course and channelled the impetus of external reform for internal purposes. Critically, through this process of repositioning and refocusing there is an increased capacity to develop, reshape and sustain initiatives without capitulating to external pressure. For example, while we cannot mirror National Curriculum notions of entitlement to a content curriculum, one which is neatly parcelled up between the ULIE and its partner schools for delivery according to predetermined criteria, we can provide an entitlement to certain course principles (which govern the design of the programme, the nature of the partnership and the image of what it means to be a teacher) and to curriculum experiences (ways of working) which act as benchmarks of designed-in-quality. This simply confirms that curriculum planning is best seen not as a technical exercise, but as an artistic and political process (cf. Huebner, 1975).

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

Critique of the Reflective Practitioner Problematising Reflective Practice We have found the reflective practitioner motif (after Schn, 1987) increasingly perplexing. It is not just that beginning teachers soon tire of repeated exhortations involving the R word, seeing it as a rather esoteric diversion from mastering the skills and content of teaching. It is rather that in trying to explicate what we mean by this shorthand, a growing number of questions have been corroding our confidence in its efficacy. For example: x can we say what this thing called reflective practice is (can it be described or its impact felt)? x can we specify when it happens (and under what conditions and within what timeframe)? x can we be certain whether it can be taught/learned (and by whom) and what research evidence is there that it is effective? x do we really know what it is for (is it, inter alia, a necessary condition for becoming a teacher or a criterion for distinguishing professional from non-professional practice)? x do we claim (or imply) (or sound like we claim) that reflective practice provides a theoretical underpinning for ITE? or, that reflective practice provides an epistemology of everyday professional practice? Work with beginning teachers demonstrates the difficulty in specifying reflection in relation to practice. If reflection only results from certain strategic forms of thinking (framing/reframing), then how does reflection in action take place (i.e. under extreme time pressure or in relation to the routine?) What distinguishes reflection in action from good intuition, good common sense or sound judgement based on constructive self-criticism? If it is cued primarily by the unpredictable, can we really accept it as a model for learning how can learners be prepared to deploy it? Does not the traffic it exhorts between action on the one hand and analysis, interpretation and so on, on the other, betoken a rather one-sided emphasis

358

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

on cognition over action and being? Can reflective practice really function as some sort of master metaphor for ITE as set against craft-apprenticeship? Is this not to perpetuate a disparaging view of practical activity as intrinsically an inferior sort of thing; to continue to downgrade local knowledge both inherited and contextualized norms and actual lived experiences, as opposed to ... abstract knowledge and reinforce a culture of critical rationality disembedded from the immediacies of context? (Scott, 1997, p. 21). A Response: the reflective professional Relevant research does suggest that working effectively at a challenging task requires significant amounts of reflection and the development of thoughtfulness (Diamond, 1995); there is also evidence to indicate that the intending professional should be encouraged to develop reflective approaches to demanding situations (Hatton & Smith, 1995). As a function of the wider professional role, beginning teachers learn that they have methods at their disposal which can help them deliberate on their actions, in particular by reflecting inwardly on the basis for their actions (their thinking and decision-making in relation to aims and methodology) and outwardly on the consequences of their actions (the interactions between pedagogy and social context). Such deliberation is likely to be stimulated and sustained by collegial relationships and peer support; indeed, rather than individualistic approaches to reflection premised entirely on notions of self-dialogue, the need for a communal (collaborative-partnership) context for thoughtful discourse is paramount. It can be said to include forms of reflection whereby both critical and creative relationships are discerned between concepts, of thinking about your own thinking, or metacognition (or theorising), involving both strategies that can be learned and sensibilities that can be developed: x how to think strategically about broader issues and aims as well as, but distinct from, thinking about tomorrows lesson; x how to grasp emergent ideas and secure their progressive amplification into patterns of coherence; x how to step back as a specialist and consider to honestly re-evaluate what you are doing from a general perspective and bring personal experience, knowledge and routine under critical scrutiny; x how to identify and describe problems in open and useful ways and in context here the excavation of the hidden is as important as the explication of the given (Abbs, 1994, p. 29); x how to give voice to ones own ideas and also to listen to and understand what others are really saying; x how to talk with children, parents and other teachers with precision and in an effective diagnostic frame; and x a disposition to relate educational values to real life and to develop an ethical stance intellectual honesty, vocational integrity and a wider educational citizenship.

359

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

Relevant Course Features These are designed not just to develop knowledge, understanding and skills, but also to cultivate a thinking that actually works through and on beginning teachers lived experience their existence as teachers-in-the-making and therefore develops their character as professionals. Examples include the following. x Profile Tasks, e.g. The kind of teacher I want to be. Such overtly reflective forms of writing contribute to the beginning teachers portfolio. Their purpose is to catch the minds activity in emergent phases (Abbs, 1994, p. 30) and to use beginning teachers metaphors of teaching to reflect upon their underlying assumptions and to inform their subsequent response to teaching dilemmas. x Structured curriculum planning-implementation-evaluation tasks; based on a context-sensitive needs analysis, beginning teachers work in pairs to produce a trial-run package, which is then publicly evaluated involving descriptive and dialogic reflection on action. x Provision of thinking frameworks introduced and subsequently guided by the beginning teachers tutor and co-tutor (mentor) in school; for example: (a) the challenging review of lessons in which the beginning teacher is shown how to follow a sequence of dialogue with co-tutors, such as: Describe (what happened?) Inform (what were the lessons intentions?) Challenge (why was it done in that way?) Reconstruct (what alternatives are there? When are these more appropriate?) (b) aids to deliberation: practical judgements are: Informed (knowledge/theory/assumptions) Contingent (context/insight/perspective) Developing (can change/be refined) Notions of a Scholarship of Teaching Some Issues Eraut (1994, pp. 102ff.) offers a perceptive observation concerning the primitive state of our methodology for describing and prescribing a professions knowledge base. Many areas of professional knowledge and judgement have not been codified; and it is increasingly recognised that experts often cannot explain the nature of their own expertise ... The field is underconceptualised. On the other hand, it can also be argued that the field suffers from a form of conceptual inflation, claims being made for the scientific underpinnings afforded by curriculum and pedagogic theory which quite outstrip the actual power of various frameworks and viewpoints (see Carr, 1995).

360

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

Furthermore, Ron Barnett (1994) has argued forcibly for an understanding of the limits of competence; definitions of operational competence on the one hand, and academic competence, on the other, carry a narrow conception of human being which is limiting and inappropriate to the modern age. Scholarship and the PGCE Student (beginning teacher) Postgraduate teacher education and training finds itself caught up in this in a particularly intense manner: not only is the purpose of training under critical review, and who should be responsible for supplying it, but the role of the HE institution is strangely difficult to specify or define. We may say it is to offer beginning teachers scholarship, and the opportunity to engage in it, but what actually do we mean by this and in what way is it relevant to their preparation as teachers? Is it worth the blood, sweat and tears, or is it an imposition, and a disingenuous one at that? There needs to be a fresh look at scholarship that takes us beyond the tired old research versus teaching and theory versus practice debates. To be sure, we want our teachers to be scholars (dont we?). The Scholarship of Teaching Reconsidered Scholarship, it is argued, should consist of: x discovering knowledge (an essential university function encapsulated in research); x integrating knowledge (recognising the importance of context and larger representational patterns); x applying knowledge (is knowledge useful ... and in what way? This implies an ethical question: what is knowledge used for?); and x sharing knowledge (the sacred art of teaching ... engaging others, especially the uninitiated and not simply the peer group, through presentation and publication). Thus, Discovery without integration is pedantry, and discovery and integration without application is irrelevance. Scholarship without sharing is discontinuity (Boyer, 1995, p. 19). A concern for truth, wisdom and life, problematic as it continues to be, must remain the animating concern of scholarship in the HE institution if beginners are to understand what educative teaching is for and how that relates to their sense of where they are themselves going in their lives (Smith, 1996, p. 208). This analysis is complemented and given greater conceptual specificity by Rice (1992), who has identified three distinct elements of the scholarship of teaching: x the synoptic capacity ability to draw together strands of a field of study in a way that provides both coherence and meaning, to place what is known in context and open the way for connection to be made between the knower and what is known;

361

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

x pedagogical content knowledge the capacity to represent a subject in ways that transcend the split between intellectual substance (subject matter) and teaching process (application to the teaching context), usually having to do with metaphors, analogies and (thought) experiments that are the particular province of teachers (Shulman, 1986); and x what we know about learning scholarly inquiry into how pupils make meaning and sense out of what teachers say and do. Relevant Course Features At course level, the ULIE has addressed these questions and sought to exhibit the kinds of thinking summarised above in the following ways. 1. By valuing enquiry-based forms of working. In so doing it encourages beginning teachers to pursue both their own questions and those identified by the school through a fusion of interests. 2. Through beginning teachers integrating classroom concerns with wider school needs and considerations, with their own wider knowledge base (as partners, former career holders, etc.) and with other scholarly perspectives (including the educational and subject literature). 3. Through beginning teachers having to demonstrate that they can apply knowledge appropriately to the particular context in which they work, enabling them to make concrete judgements about ends and means. 4. Through beginning teachers sharing effectively: for example, their research and development project (undertaken in the second and third terms) is presented initially to school staff and peers, then (in a more formal format) to tutors. In short, beginning teachers should be able to question, enquire and integrate: question to create better and clearer understanding; enquire for more in-depth knowledge and experience; integrate what is being learned (across the course) with practice and actualisation. They are trained to become critical users of knowledge; to distinguish information from knowledge, to recognise (with John Dewey) that ideas are usually plans of action and (with William James) that they too have to be judged by their cash value in effect, that they must buy purchase in reality. The Role of Experience in Relation to Meaning Questions and Complexities Experience is sometimes presented as a panacea but the fact that we learn from experience and what we learn from experience are different things. Can we characterise what we mean by experience how does it relate to teaching, in what sense is it central to learning, and how does experience correlate with meaning? There are difficulties in identifying and clarifying experience as a concept; it denotes different things in different contexts and has come to carry considerable connotative baggage. In particular, its association in our

362

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

culture with intemperate individualism (in which personal experience is self-validating and unquestionable) is problematic in relation to the notion of a learning community; furthermore, the assumption that unmediated experience contributes the raw material out of which we construct or create meaning, is philosophically naive. A Response: experience as medium but not sole mediator of learning Nicholas Maxwell suggests that experience is best understood in the widest possible sense as human experience, what we acquire as we attempt to do things, partly succeeding and partly failing (Maxwell, 1992, p. 60). As such, it is both a process (necessarily) and an achievement (contingently). In terms of teaching:

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

experience is in general what is [being] learned about how to do relevant and appropriate things of value as a result of actions, policies, principles and programmes being implemented, and in terms of which those same actions, and the policies and aims that they embody, are to be judged. (Maxwell, 1992, p. 58)

As educators committed to lifelong learning, we take the view that genuine learning occurs when people reflect on their experience and test their understanding. This reflection involves drawing upon previous experience, including possibly an already established role and expertise in life (Finnegan, 1992, p. 19), as well as listening and attending to what we are told by those in a position to help us interpret experience. In new contexts we may need support from experts or to consult established authorities in order to know what to make of things and how to learn from them. Thus, though experience is a necessary condition of learning, it is not necessarily a sufficient one. In acquiring professional capacities:

Experience needs to be seen as an antecedent to the two concepts theory and practice and, as such, experiencing plays a key role in our attempts to get to grips with the problem of merging theory and practice. Experience makes practice and practising gives us experience to think about, to reflect on and to begin to either theorise for ourselves or match our experience and practice with the theories of another. (Slater & Rask, 1983, p. 183)

Experience is central to learning, it seems to us, in the sense that it provides the crucible through which theoretical frameworks and repertoires of practice are tested, and then appropriated or discarded. However, the prevalent tendency to couch professional (public) views purely in terms of individual experience arises from a confusion between feeling things and expressing them. We may be meaning-making creatures, but that meaning-creating must go on in a manner appropriate to the sphere in which it is occurring (cf. Sennett, 1986). Of fundamental importance for teacher education is something like Eisners concept of representation: the

363

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

process of transforming the contents of consciousness into a public form so that they can be stabilised, inspected, edited, and shared with others (Eisner, 1993, p. 6). Thus, beginning teachers need a language with which they can share their personal experience and learn from others public experiences (Tann, 1993, p. 68). Moreover, experience is contingent and derivative in the sense that no meaning is entirely immediate to human consciousness, but is always mediated to us symbolically, if only through human language. Especially noteworthy in this respect is the way the developing partnership in training and learning with schools has served to mediate the concept of professional experience and to relocate it semantically in a broader milieu. Relevant Course Features

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

Experience is granted through the careful identification for the beginning teacher of particular ways of working; it is expected that personal experience will provide one horizon of interpretation and understanding and that the traditions of schools and teachers will provide another which are then brought together in an intepretative zone. For example, the assignment based on research and development projects encompasses beginning teachers prior learning and experience, is grounded in a context (Area Based Study), is framed by a getting-in-touch agenda (School Focused Enquiry) and is sanctioned with reference to the learning community and the ethics of research. As such it is refined through being progressively placed in the public arena: deliberation and reflection are fostered through staged proposals and presentations in which experience is stretched in pursuit of inter-subjective confirmation from mentors and peers; finally it is re-presented formally to meet externally validated whole course criteria. The Role of Research in the Learning Community Questions and Qualifications Research is very much in the limelight. While educationists acknowledge that there has been much critical debate about the quality, credibility and impact of educational research (Bassey, 1994, p. 18), HE institutes continue to regard themselves as being research led and as contributing to professional improvement. In a parallel development, under the auspices of the Teacher Training Agency, teaching is currently being postulated as a research-based profession. But what is educational research? What can it tell us? What is it good for? Who are its primary users? We need convincing responses to such questions, ones in which the wider community parents, governors and teachers, as well as beginning teachers can believe. According to Eisner (1993), We do research to understand. Meaning or understanding is constructed on the basis (the bedrock) of experience, ... and that experience in significant degree depends on our ability to get in touch with the qualitative world we inhabit (p. 5). For

364

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

Eisner, getting in touch is a conscious activity and a cognitive event. It concerns construal, not (simply) discovery. It requires mental application and engagement. Of relevance is the fact that, although we may expect to learn from research conducted by others, we may expect to learn a lot more through research undertaken by ourselves or those fairly close to us who share the same or similar qualitative world. Teacher as Researcher As Eisner puts it, We try to understand in order to make our schools better places for both the children and the adults who share their lives there (1993, p. 10). It can be argued that we do this as reflective professionals, for example in our search for more effective ways to teach X. But there are occasions when the careful identification of a deeper or more nuanced question or issue, which may yield to systematic study, is an appropriate action: the teacher becomes researcher and requires the knowledge, dispositions and skills to make good judgements and wise decisions based on evidence. To emphasise the significance of the previous passage: we are not interested solely in a persons capacity to find out something, but also in their ability to organise and exploit it. Furthermore, as Barnett (1994, p. 75) has noted, genuine learning is a sharing and collective activity, in which we test out what we believe we have learnt in the company of others. Teachers who share such an understanding are sceptical of those who offer them a canon of research to be assimilated. They are more in tune with their context, capable of observing and describing it and (to use Eisners term) representing it in ways that make it comprehensible to prospective users. If we believe in the efficacy of this approach and want to enhance the status of research among aspiring teachers, then the place to begin to encourage the attitudes, skills and knowledge which this requires is during their initial education and training. Relevant Course Features Beginning teachers are encouraged, through various means including course documentation and dialogue with tutors, to understand the significance of the term education both generally and in the specific context of the PGCE. To use Eisners words again, Education itself is a mind-making process (1993, p. 5). The course strives to remain anchored in the university setting, but closely tied to the realities and practical problems of schools (Grimmett, 1995, p. 205). The structure of the partnership in training and learning seeks to help beginning teachers understand their own responsibility in acquiring entitlement knowledge: humans do not simply have experience; they have a hand in its creation, and the quality of their creation depends upon the ways they employ their minds (Eisner, 1993, p. 5).

365

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

All beginning teachers undertake a sequence of shared enquiries: Area Based Study; School Focused Enquiry; and Research and Development Project (R & D). The R & D project is often based on a question about organisation, method, motivation, ethos, purpose or achievement suggested by the school. Its outcomes are reported back to the school and in a more elaborate form to tutors. That is, it is both user-directed and user-responsive; while through being systematically stabilised, critically inspected, edited and shared in different public forums with others, it has the potential to challenge (and in our experience) also to change the status quo. Theory, Practice and Models of Learning for Professional Formation. Some (Ongoing) Issues Margaret Wilkin (1996) has recently presented an analysis reiterating the claim that maintaining a proper balance between theory and practice is central to the culture of initial teacher training. Indeed, it is at least arguable that this cultural tenet is the defining preoccupation of teacher trainers. Yet, as David Carr observes, the relevance of theoretical studies to professional practice is by no means as clear as teacher trainers have sometimes supposed (Carr, 1995, p. 311); defences of the professional value of theory in teacher education have inclined to a conceptually inflationary estimate of its involvement in professional practice (Carr, 1995, p. 312). Moreover, if we are appropriately self-critical, we have to acknowledge that teacher educators, under the influence of university culture, tend to have an excessive faith in the power of ideas. Furthermore, this leads them [teacher educators] to under-estimate the enormous problems novices have in integrating theory with practice (Tom, 1995, p. 128). As Kemmis (1995, p. 13) notes, even the reflective practitioner model often seems to presuppose a one-sided, rather rationalistic view of theorising, emphasising the power of ideas to guide or even direct action, rather than the way action and the circumstances of action also shape our ideas. Notwithstanding this, some have argued that effective teaching requires a knowledge of concepts, or variables, and their interrelationships in the form of strong or weak laws, generalisations, or trends; also, the findings of educational research are no longer portrayed as solutions to problems but rather as findings and concepts that teachers must apply flexibly to particular contexts (quoted in Tom, 1995, p. 121). The worry is that an emphasis on practice without the accompanying theory and reflection may not be the reform impetus that will prepare teachers for continuous learning or help schools become learning communities (so, for example, Edwards, 1992). How should the tensions and dichotomies inherent in the theory-practice continuum be reconciled? In theory? In practice? Can we solve the dilemmas with sophistication and subtlety, without dissolving them? Can we find a way of inhabiting theory-practice dualism, by not leaving it as mere abstraction, but revealing it as an inchoate human creation inscribing our relations to gaps, absences and ambiguities in our

366

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

understanding as we endeavour to make our situational appreciation of the complex business of education. Theory and Practice as Mutual Reciprocators in ITE The first thing to say is that perplexities of theory and practice have attracted no shortage of thoughtful contributions from eminent educationists and others we make no claim to boldly go where none have gone before! Effecting a powerful integration of theory and practice has always been an educational ideal. It seems unhelpful to attempt an account of professional formation by reducing theory to practice, or vice versa: both theory and practical experience are needful. But theory and practice should not be thought of as inhabiting separate worlds; many years ago, James Welton (1906, p. 17) postulated that educational theory is practice become conscious of itself, and practice is realised theory. The formulation may be questionable, but the interface he recognised is crucial. Theory and practice are not oppositional or hierarchical; they are better conceived as reciprocal. As Walsh (1993, p. 43) puts it, deliberated, thoughtful (reflective and common-sense) practice is not just the target, but is itself a major source of educational theory. Or, as Ryle (1966, p. 27) observed, Intelligent practice is not a step-child of theory. On the contrary, theorising is one practice amongst others and is itself intelligently or stupidly conducted. There is a growing recognition that theory should be conceived not primarily in terms of underpinning, informing or fashioning practice, but rather more as educating supporting, enriching, and stimulating people engaged in the process of making sense of their professional life-world (Furlong & Smith, 1996, p. 7; and cf. Carr, 1995). The rubric of partnership provides new opportunity for merging theory and practice into the kind of continuum for which Grundy has coined the term practique an interactive and reflexive pedagogical process of authentic professional action presupposing that the relationship between knowledge and action is not direct; rather it is dependent upon deliberation, shared understanding and intention (Grundy, 1987, p. 181). It is then within the province of practitioners to link theory and practice integrally from the outset: to exercise practical judgement, to take initiatives and to control their own practice. Relevant Course Features The ULIE course takes this forward and seeks to promote an understanding which posits greater congeniality, not necessarily congruity, between theory and practice. It recognises that theory, or at least theorising, is a distinctive activity which calls for a certain acuteness of apprehension and conceptual finesse, in turn requiring of the beginning teacher particular skills, attitudes and dispositions. These are cultivated through:

367

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

x ensuring that practical teaching experience is the essential point of integration between educational principles, values and theory and the practice of teaching[4]; x R & D projects, which can increasingly be seen as educational enquiries into a complex of personal puzzles, institutional dark matter and other problems. They require beginning teachers to theorise and to think things through rigorously and in some depth and with imagination for different possibilities, and to examine ... presuppositions (Smith, 1996, p. 197); and x key note lectures, from leaders in the field, which seek to bring research-led state of the art perspectives into contact with state of the practice norms and conventions so as to stimulate a professional conversation between tutors, teachers and beginning teachers.

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

Conclusions As we mentioned in the introduction, the kind of thinking represented under each of our six headings (what we have called problematics) has been the source of a considerable injection of energy and animus into the process of moving to and consolidating a partnership course. Perhaps our overriding concern has been to provide a realistic prospect of productive partnership and hence to fashion the foundations of a course with inner strength, one which we feel is strong enough to withstand the impact of vicarious external pressures, and yet to respond openly and effectively to change. The goal, of course, is to produce new teachers whose capacities to engage intellectually and practically with pupils and colleagues have been maximally expanded and refined. We want to be as ambitious with out student teachers as we wish them to be ambitious with their pupils. However, just as important in our view, is a second goal which has to do with the whole project of initial training in the UK (see, DfEE, 1998) and the context of the extraordinary attacks it has received in recent years. Such attacks have yet to attract a concerted and persuasive counter-argument from the profession at large to the effect that ITE is a necessary precondition to becoming a teacher. In fact rather than argue that the HE component of ITE is indispensable in a way that, for example, Eraut (1985, p. 117) claims, it encompasses enhancing the knowledge creation capacities of individuals and professional communities, there has been a rather noticeable silence on this matter from teachers. We suspect that for there to be more positive and effective advocacy of ITE, the teacher educators need to deploy better arguments. Most importantly, the client group, the beginning teachers, need to understand and to appreciate the value-added effect from their PGCE experience; similarly, the natural laboratory or studio of teacher education, the schools, need to understand and appreciate the professional benefits that accrue from being centrally involved. It is now generally recognised that the teacher is a key figure in the development of a learning society. Such a society, if it is to be motivated by a vision of thoughtfulness

368

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

and human flourishing, will need intelligent schools among aspiring teachers, the capacity for professional independent and innovative practice is likely to be valued ever more highly in tomorrows educational climate. It is in consciously orchestrating a vision of teaching as practically based but intellectually grounded that HE can furnish a context in which it makes good sense to acknowledge that its relationship to teacher education is crucial to the quality and independence of the teaching profession. Perhaps, if far-sighted enough, HE can replenish the academy for those skills and dispositions cultivated by the intellectual virtues that produce the ability to cooperate in ways aimed at knowledge-building and continuous growth within professional communities. This article has case studied one PGCE course as a basis for moving at least part way towards achieving such a goal in a more convincing manner.

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

Correspondence Michael Totterdell, ITE Office, Institute of Education, University of London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL, United Kingdom. Notes

[1] Partnership in training and learning is a formulation which we have adopted to signify a course orientation in which all course participants are seen as both learners and teachers, with skills, insights and knowledge to share and acquire. For detailed accounts, see Heilbronn & Jones (1997). [2] We use the term problematic in its technical sense, as a sensitising concept which provides a rudimentary organisation of a field of study that yields clues as to what is important and what peripheral (Abrams, 1982, p. vx). As such it is like an archaeologists flag, indicating an important site worthy of careful investigation. It leads us to ask some appropriate questions, but cannot in and of itself give the answers. [3] Elsewhere we have argued that a centrist position should help to recover a more perspicacious understanding of the business we are in (Totterdell & Lambert, 1997, p. 181ff). [4] The designation of Practical Teaching Experience is a deliberate move away from Teaching Practice; it reflects the fact that we have chosen the school, rather than the individual classroom, as the venue for training, believing beginning teachers need exposure to the wider culture of the institution in which they are working so that they might better understand the impact of that larger environment on what they do through forms of action research. See Heilbronn & Jones (1997).

References

Abbs, P. (1994) The Educational Imperative: a defence of Socratic and aesthetic learning. London: Falmer Press. Abrams, P. (1982) Historical Sociology. Shepton Mallet: Open Books. Ball, S.J. (1994) Education Reform. Buckingham: Open University Press.

369

M. TOTTERDELL & D. LAMBERT

Barnett, R. (1994) The Limits of Competence: knowledge, higher education and society. Buckingham: Open University Press. Bassey, M. (1994) Why Lord Skidelsky is so wrong, The Times Educational Supplement, 21 January, p. 18. Boyer (1995) Glancing backward, looking forward: traditions of higher education within the USA and their prospects, Reflections on Higher Education, 7, pp. 7-31. Carr, D. (1995) Is understanding the professional knowledge of teachers a theory-practice problem? Journal of Philosophy of Education , 29, pp. 311-331. Collarbone, P. & MacGilchrist, B. (1996) Value-added teacher training: teacher partners mine a rich seam at the chalk face, The Times, 14 June, p. 10. Department for Education (1992) Initial Teacher Training (Secondary Phase), Circular 9/92. London: HMSO. Department for Education and Employment (1998) Teaching: high status, high standards, Circular 4/98. London: HMSO. Diamond, M. (1995) The significance of enrichment, The In Report (July/September). Edwards, T. (1992) Issues and challenges in initial teacher education, Cambridge Journal of Education , 22, pp. 283-291. Eisner, E.W. (1993) Forms of understanding and the future of educational research, Educational Researcher , 22, pp. 5-11. Eraut, M. (1985) Knowledge creation and knowledge use in professional contexts, Studies in Higher Education , 10, pp. 117-133. Eraut, M. (1994) Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Falmer Press. Finnegan, R. (1992) Recovering academic community: what do we mean? Reflections on Higher Education , 4, pp. 7-23. Furlong, J. & Smith, R. (Eds) (1996) The Role of Higher Education in Initial Teacher Training. London: Kogan Page. Grimmett, P. (1995) Reconceptualising teacher education: preparing teachers for revitalized schools, in M. Wideen & P. Grimmett (Eds) Changing Times in Teacher Education: restructuring or reconceptualization? pp. 202-225. London: Falmer Press. Grundy, S. (1987) Curriculum: product or praxis? Lewes: Falmer Press. Harland, J. (1992) PGCE Camden Area Based Scheme 1991-1992: an evaluation. London: ULIE. Hatton, N. & Smith, D. (1995) reflection in teacher education: towards definition and implementation, Teaching and Teacher Education, 11, pp. 33-49. Heilbronn, R. & Jones, C. (Eds) (1997) New Teachers in an Urban Comprehensive School: learning in partnership. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books. Holland, G. (1995) Are we really educating for the 21st century and the needs of tomorrows workforce? Paper read to the Foundation for Manufacturing and Industry, 4 October, pp. 1-7. Huebner, D. (1975) The task of the curricular theorist, in W. Pinar (Ed.) Curriculum Theorising: the reconceptualists. Berkeley: McCutchen. Kemmis, S. (1995) Prologue, in W. Carr, For Education: towards critical educational inquiry, pp. 1-17. Milton Keynes: Open University Press. Lambert, D. & Totterdell, M. (1995) Crossing academic boundaries: clarifying the conceptual landscape in initial teacher education, in D. Blake, V. Hanley, M. Jennings & M. Lloyd

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

370

RECONCEPTUALISING INITIAL TEACHER EDUCATION

(Eds) Researching School-based Teacher Education , pp. 13-25. Aldershot: Avebury Press. Maxwell, N. (1992) What the task of creating civilisation has to learn from the success of modern science: towards a new enlightenment, Reflections on Higher Education , 4, pp. 47-69. Padgham, R.E. (1983) The holographic paradigm and postcritical reconceptualist curriculum theory, Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 5, pp. 132-143. Porter, J. (1996) The James Report and what might have been in English teacher education, in C. Brock (Ed.) Global Perspectives on Teacher Education, pp. 35-46. Wallingford: Triangle Books. Rice, R.E. (1992) Towards a broader conception of scholarship: the American context, in T. Whiston & R. Geiger (Eds) Research and Higher Education: the United Kingdom and the United States, pp. 117-137. Buckingham: Open University Press. Ryle, G. (1966) The Concept of Mind. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. Schn, D. (1987) Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Scott, P. (1997) The crisis of knowledge and the massification of higher education, in R. Barnett & A. Griffin (Eds) The End of Knowledge in Higher Education , pp. 14-26. London: Cassell. Sennett, R. (1986) The Fall of Public Man. London: Faber & Faber. Shulman, L.S. (1986) Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching, Educational Research, 4, pp. 63-76. Slater, F. & Rask, R. (1983) Geography teacher education, European Journal of Teacher Education , 6, pp. 183-189. Smith, R. (1996) Something for the grown-ups, in J. Furlong & R. Smith (Eds) The Role of Higher Education in Initial Teacher Training , pp. 195-212. London: Kogan Page. Tann, S. (1993) Eliciting student teachers personal theories, in J. Calderhead & P. Gates (Eds) Conceptualizing Reflection in Teacher Development , pp. 53-69. London: Falmer Press. Tom, A.R. (1995) Stirring the embers: reconsidering the structure of teacher education programs, in M. Wideen & P. Grimmett (Eds) Changing Times in Teacher Education: restructuring or reconceptualization? pp. 117-131. London: Falmer Press. Totterdell, M. & Lambert, D. (1997) Designing teachers futures: the quest for a new professional climate, in A. Hudson & D. Lambert (Eds) Exploring Futures in Initial Teacher Education , pp. 178-202. London: Bedford Way Papers. Walsh, P. (1993) Education and Meaning: philosophy in practice. London: Cassell. Welton, J. (1906) Principles and Methods of Teaching. London: University Tutorial Press. Wideen, M.F. (1997) Exploring futures in initial teacher education the landscape and the quest; exploring futures in initial teacher education: a fin de millenium perspective, in A. Hudson & D. Lambert (Eds) Exploring Futures in Initial Teacher Education , pp. 3-42 & pp. 429-456. London: Institute of Education, Bedford Way Papers. Wilkin, M. (1996) Initial Teacher Training: the dialogue of ideology and culture. London: Falmer Press. Wilkin, M. & Sankey, D. (1994) Collaboration and Transition in Initial Teacher Training. London: Kogan Page.

Downloaded by [187.244.165.6] at 20:06 17 January 2013

371

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Department of Labor: Errd SWDokument151 SeitenDepartment of Labor: Errd SWUSA_DepartmentOfLaborNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wolof Bu Waxtaan Introductory Conversational WolofDokument15 SeitenWolof Bu Waxtaan Introductory Conversational WolofAlison_VicarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Little Science Big Science and BeyondDokument336 SeitenLittle Science Big Science and Beyondadmin100% (1)

- Marissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Dokument9 SeitenMarissa Mayer Poor Leader OB Group 2-2Allysha TifanyNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Balbharati STD 1 PDFDokument86 SeitenEnglish Balbharati STD 1 PDFSwapnil C100% (1)

- Assignment Form 2Dokument3 SeitenAssignment Form 2api-290458252Noch keine Bewertungen

- ICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalDokument203 SeitenICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalZe OmNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Lesson Plan in GrammarDokument4 SeitenA Lesson Plan in GrammarJhoel VillafuerteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hit ParadeDokument20 SeitenHit ParadeNishant JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- My HanumanDokument70 SeitenMy Hanumanrajeshlodi100% (1)

- The Sound of The Beatles SummaryDokument6 SeitenThe Sound of The Beatles Summaryrarog23fNoch keine Bewertungen

- MTB Mle Week 1 Day3Dokument4 SeitenMTB Mle Week 1 Day3Annie Rose Bondad MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foundation of EducationDokument15 SeitenFoundation of EducationShaira Banag-MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matalino St. DM, Government Center, Maimpis City of San Fernando (P)Dokument8 SeitenMatalino St. DM, Government Center, Maimpis City of San Fernando (P)Kim Sang AhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Program IISMA 2021 KemdikbudDokument8 SeitenProgram IISMA 2021 KemdikbudRizky Fadilah PaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebau Exam 2020Dokument4 SeitenEbau Exam 2020lol dejame descargar estoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of The Nurse in Health Promotion PDFDokument1 SeiteThe Role of The Nurse in Health Promotion PDFCie Ladd0% (1)

- Virginia Spanish 2 SyllabusDokument2 SeitenVirginia Spanish 2 Syllabuskcoles1987Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aiming For Integrity Answer GuideDokument4 SeitenAiming For Integrity Answer GuidenagasmsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building An Effective Analytics Organization PDFDokument9 SeitenBuilding An Effective Analytics Organization PDFDisha JaiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICT Curriculum For Lower Secondary 2Dokument40 SeitenICT Curriculum For Lower Secondary 2Basiima OgenzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feedback Control System SyllabusDokument3 SeitenFeedback Control System SyllabusDamanMakhijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Level 4 UNIT - 07 - Extra - Gram - ExercisesDokument8 SeitenLevel 4 UNIT - 07 - Extra - Gram - ExercisesFabiola Meza100% (1)

- Principles & Procedures of Materials DevelopmentDokument66 SeitenPrinciples & Procedures of Materials DevelopmenteunsakuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mother Tongue: Kwarter 3 - Modyul 4.1Dokument34 SeitenMother Tongue: Kwarter 3 - Modyul 4.1Vicky Bagni MalaggayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Economy and Market IntegrationDokument6 SeitenGlobal Economy and Market IntegrationJoy SanatnderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Second Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)Dokument217 SeitenSecond Final Draft of Dissertation (Repaired)jessica coronelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningDokument22 SeitenThe Impact of Integrating Social Media in Students Academic Performance During Distance LearningGoddessOfBeauty AphroditeNoch keine Bewertungen

- References - International Student StudiesDokument5 SeitenReferences - International Student StudiesSTAR ScholarsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Dokument33 SeitenEligible Candidates List For MD MS Course CLC Round 2 DME PG Counselling 2023Dr. Vishal SengarNoch keine Bewertungen