Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Insurance Law

Hochgeladen von

WayneLawReviewCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Insurance Law

Hochgeladen von

WayneLawReviewCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

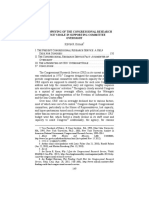

INSURANCE LAW STEPHANIE MARINO ANDERSON AND ANTHONY J. SUKKAR I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 911 II.

DECISIONS BY THE MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS ......................... 913 A. Uninsured-Underinsured Motorists ........................................... 913 B. No-Fault ..................................................................................... 917 1. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3107 Allowable Expenses ................................................................................... 917 2. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3114 Priority of Insurers ................................................................................ 921 3. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 500.3142 Overdue Benefits ...................................................................... 925 4. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3148 Attorney Fees ....... 925 C. Additional Cases from the Michigan Court of Appeals ............. 927 III. DECISIONS OF THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT ............................ 929 IV. DECISIONS OF THE U.S. DISTRICT COURTS ..................................... 937 A. Cases Interpreting Michigan Law .............................................. 937 B. Additional United States District Court Cases........................... 939 V. DECISIONS OF THE U.S. COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT ................................................................................................. 948 A. Cases Interpreting Michigan Law .............................................. 948 B. Additional Cases from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit .................................................................................... 949 VI. DECISIONS OF THE U.S. SUPREME COURT ...................................... 953 VII. CONCLUSION .................................................................................. 954 I. INTRODUCTION In 2011 and 2012, the Michigan Court of Appeals, Michigan Supreme Court, United States District Courts for the Eastern and Western Districts of Michigan, and United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit all issued significant rulings which pertain to the interpretation and enforcement of contractual insurance policies between insureds and insurance companies. Courts typically try to enforce insurance policies as written, and often look to state and federal statutes, legislative intent, and public policy when rendering their decisions.

Shareholder, Harvey Kruse, P.C. B.S., 2001, Michigan State University; J.D., 2004, cum laude, Wayne State University.

911

912

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

The purpose of this Survey is to cite court rulings in which a particular court found that the insured is or is not afforded insurance coverage for a particular act or event and to discuss the reasons why each court reached its decision. Most decisions of the Michigan Court of Appeals that relate to insurance law are unpublished and accordingly do not provide binding precedent in this jurisdiction.1 Unless an unpublished decision is significantly distinct from a prior published opinion, it will not be reported in this Survey review. During this Survey period, the Michigan Legislature introduced House Bill 4936, which proposed a consumer choice to Michigans stringent No-Fault Act.2 This reform bill claimed to address problems with the No-Fault Act, namely Michigan motorists pay the highest autoinsurance rates in the country3 and Michigan is the only state that provides unlimited, lifetime medical care to injured persons in car accidents.4 The proposed reform seeks to change unlimited medical care following an auto accident, allowing drivers to opt for auto insurance with $500,000, $1 million or $5 million limits in bodily injury coverage.5 Payments to health care providers would also be capped.6 This

legislation received immense attention on all fronts with strong lobby groups on both sides of the issue.7 Currently, the bill seems to have stalled in the legislature.8

1. MICH. CT. R. 7.215(C) (2012). 2. H.B. 4936, 96th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Mich. 2011) (introduced by Rep. Lund). See Pete Lund, Michigan House and Senate Introduce Cost-Saving Insurance Reform for (Sept. 14, 2011), Motorists, GOPHOUSE.COM http://www.gophouse.com/readarticle.asp?id=7824&District=36. 3. Car Insurance Costs on the Rise Again, Vermont Leads for Cheapest Rates, MOTOR TREND, Mar. 14, 2011, available at http://wot.motortrend.com/car-insurancecosts-rise-again-vermont-leads-cheapest-rates-37977.html#axzz2IckdDZNs (stating Michigan motorist pay about $1,000 per year more than the national average). CATASTROPHIC CLAIMS ASSOCIATION, 4. See generally MICHIGAN http://www.michigancatastrophic.com/ (last visited Mar. 4, 2013). 5. H.B. No. 4936, 96th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Mich. 2011). 6. Id. 7. Tony Dearing, Michigans No-Fault Car Insurance System Needs Reform, but HB (Nov. 13, 2011), 4936 is Not the Answer, ANNARBOR.COM http://www.annarbor.com/news/opinion/michigans-no-fault-car-insurance-policy-needsreform-but-house-bill-4936-is-not-the-right-way/. 8. See MICH. LEGIS., House Bill 4936 (2011), MICHIGAN LEGISLATIVE WEBSITE, http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(urz11t2f5ztf4q55isfm0geo))/mileg.aspx?page=getobjec t&objectname=2011-HB-4936 (last visited Mar. 4, 2013).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW II. DECISIONS BY THE MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS

913

A. Uninsured-Underinsured Motorists In Dawson v. Farm Bureau Mutual Insurance Co. of Michigan, the court of appeals held that an underinsured motorist insurer was not bound by the verdict in a suit against the at-fault driver when the insurer did not give written consent as required by the insurance policy.9 The plaintiff contended that his policy with Farm Bureau entitled him to payment in the amount of the judgment in excess of the at-fault drivers policy limits.10 Conversely, Farm Bureau argued that it was not bound by the prior judgment because it had not agreed in writing to the prior judgment as required under the terms of the insurance policy.11 The trial court required Farm Bureau to pay the plaintiff $80,000 in underinsured motorist benefits.12 The court also estopped Farm Bureau from relitigating any defense to the underlying action after its dismissal based on a policy provision that precluded suit for underinsured motorist benefits until the insured exhausted all other available judgments or settlements.13 The Dawson court applied the express terms of the insurance policy, which provided that Farm Bureau will not be bound by any judgments for damages or settlements made without [Farm Bureaus] written consent.14 It found that underinsured motorist coverage is not required by the No-Fault Act, and therefore, is purely contractual.15 The court of appeals reversed, holding the plaintiff was not entitled to underinsured motorist benefits merely because he obtained a tort judgment against the at-fault driver in excess of that drivers insurance coverage.16 The court reasoned that this decision protects an insurer, by way of a policy

9. Dawson v. Farm Bureau Mutual Ins. Co., 293 Mich. App. 563, 567; 810 N.W.2d 106 (2011). 10. Id. at 564-65 (noting the at-fault drivers insurance policy limit only covered twenty percent of the judgment). 11. Id. at 566 (stating the at-fault driver did not challenge the plaintiffs claim that she was negligent or the plaintiff suffered an injury that satisfied the serious impairment standard of the No-Fault Act; in fact, the at-fault driver stipulated to the plaintiffs requested damages of $100,000, which exceeded her insurance policy limit by $80,000). 12. Id. 13. Id. at 565-66 (reasoning Farm Bureau could have participated in the underlying action and elected not to). 14. Id. at 568. 15. Dawson, 293 Mich. App. at 568 (citing Rory v. Contl Ins. Co., 473 Mich. 457, 465-66; 703 N.W.2d 23 (2005) (citations omitted)). 16. Id. at 569.

914

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

exclusion, from cases where the drivers insurer chooses not to contest any issues of liability or damages.17 In Pugh v. Zefi, the Michigan Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts denial of the insurers motion for partial summary disposition because the plaintiff did not pay for services while participating in a shared-expense carpool, which is excluded under the policy provisions.18 The underinsured policy with Farmers Insurance Exchange included a policy exclusion stating coverage does not apply when the injury is sustained [w]hile occupying [an] insured car when used to carry persons or property for a charge, [however] [t]his exclusion does not apply to shared-expense car pools.19 The operator drove the plaintiff and a colleague to work daily, and the plaintiff provided the driver with twenty dollars per week to help with the cost of gasoline.20 Because the policy did not define carpool, the court of appeals looked to dictionary definitions and other jurisdictions interpreting analogous policy language.21 The Pugh court found no requirement that a carpool needs to include a sharing of vehicles.22 The court of appeals rejected Farm Insurance Exchanges contention that the Michigan Supreme Courts decision in Burgess v. Holder23 controlled the instant case.24 The court of appeals reasoned that evidence that the plaintiff chip[ped] in the same amount of money each week did not establish that the driver was charging the plaintiff a fixed amount for services, which was at issue in Burgess.25 The Pugh court further rejected the argument that a carpool required the persons involved to be friends or coworkers.26

17. Id. 18. Pugh v. Zefi, 294 Mich. App. 393, 400; 812 N.W.2d 789 (2011). 19. Id. at 395. 20. Id. 21. Id. at 397 (quoting RANDOM HOUSE WEBSTERS COLLEGE DICTIONARY (2d ed. 1997) (defining carpool as an arrangement among automobile owners by which each in turn drives the other to and from a designated place.)); BALLENTINES LAW DICTIONARY (3d ed. 1969) (providing a car pool may be [a]n arrangement whereby two or more persons ride to work . . . on a share-the-expense agreement if only the car of one is used.). But see Gen. Accident Ins. Co. of Am. v. Gonzales, 86 F.3d 673, 674 (7th Cir. 1996) (stating one man drove four of his coworkers every day in a shared-expense arrangement in his own car for a fee of $5 per passenger); Matter of Aetna Cas. & Sur. Co. v. Mevorah, 149 Misc.2d 1011, 1013-15 (1991) (stating operator always drove several individuals to work in his van). 22. Pugh, 294 Mich. App. at 398-99. 23. 362 Mich. 53; 106 N.W.2d 379 (1960). 24. Pugh, 294 Mich. App. at 399. 25. Id. 26. Id. at 399-400.

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

915

In Westfield Insurance Co. v. Kens Service,27 the Michigan Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts finding that because the driver was not upon the truck when the accident occurred, he could not have been occupying the truck as required by the underinsured motorist policy provision. The Westfield Insurance policy for underinsured coverage included the provision that the insured be occupying a covered auto, and defined occupying as in, upon, getting in, on, out or off.28 The trial court ruled that the injured person was not covered under the policy because he operated the vehicle as a towing machineoperating the control levels, when the accident occurred.29 Also, the court found that his use was unrelated to being a driver or passenger of the truck, holding coverage depended on the insureds connectedness with the activity of being a driver or passenger.30 The court of appeals looked to the Michigan Supreme Courts decision in Rednour v. Hastings Mutual Insurance Co., which interpreted identical policy language.31 The Westfield court reasoned that while a person is not required to be physically inside a vehicle to be upon it, physical contact alone is insufficient to show that the injured person was upon the vehicle.32 The injured person contended he was upon the truck because he had both hands on it and was leaning against [it] for balance when the vehicle struck him.33 The court of appeals held this was not enough to demonstrate he was occupying the vehicle because he had been out of the vehicle for several minutes and was operating the towing controls of the truck.34 The significance of the Westfield decision is the courts conclusion that physical contact alone is insufficient to demonstrate that a person being upon a vehicle is equivalent to occupying it.35 In Chouman v. Home Owners Insurance Co., the court of appeals reversed a judgment in favor of the insured, vacated case evaluation sanctions, and remanded the case to the trial court.36 The court addressed an evidentiary issue related to evidence used for a claim of no-fault

27. 295 Mich. App. 610; 815 N.W.2d 786 (2012). 28. Id. at 612-13. 29. Id. at 614. 30. Id. 31. Id. at 615. See Rednour v. Hastings Mut. Ins. Co., 468 Mich. 241, 244-45; 661 N.W.2d 562 (2003). 32. Westfield, 295 Mich. App. at 617 (quoting Rednour, 468 Mich. at 250). 33. Id. 34. Id. at 618. 35. Id. at 617. 36. Chouman v. Home Owners Ins. Co., 293 Mich. App. 434, 436; 810 N.W.2d 88 (2011).

916

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

benefits in an underinsured motorist benefits claim as well as issues related to the requisite standard needed to establish a serious impairment of body function.37 First, the court of appeals held that evidence that the insured stopped receiving medical treatment related to her alleged injuries because a third party-payor terminated payments was relevant to refute any argument by the underinsured insurer that medical treatment was no longer necessary.38 Second, the court of appeals held that the defendant insurers consent to plaintiffs settlement for the direct claim for both PIP and third party benefits was not admissible, as it had little tendency to make the existence of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more probable or less probable as set forth in MRE 401.39 The court found no compromise of any dispute because the policy provisions for uninsured motorist coverage required the defendant insurer to consent to the settlement.40 The court of appeals rejected the argument that an insurers consent to a settlement between the at-fault driver and the injured party was itself a compromise of a dispute between the insurer and the injured party for underinsured motorist benefits.41 The court of appeals found this evidence inadmissible under MRE 401 as the danger of unfair prejudice outweighed its probative value for policy reasons.42 The Chouman court further held that a directed verdict was improper because reasonable minds could differ as to the nature and extent of the injuries sustained under MCLA Section 500.3135(7), despite the fact there was no dispute that the insured suffered from a bulging disc in her spine.43 The court of appeals conceded that there could be no dispute that the spine is an important body function; however, there remained a genuine dispute whether the objectively manifested abnormalities in [the plaintiffs] spine and nerve continue to be impairments.44 Defense expert, Dr. DeSantis, offered testimony that she was unable to find an

37. Id. 38. Id. at 437-38. 39. Id. at 439-40 (quoting MICH. R. EVID. 401 (2012)) (failing to find the admission of this evidence to warrant reversal because the settlement was only incidental because the jury knew the defendant had not given its consent because it believed plaintiffs claims to be meritorious, but because defendant had nothing to lose.; finding that the jury never considered this evidence as the trial court granted plaintiffs request for directed verdict). 40. Id. at 439. 41. Id. at 439-40. 42. Chouman, 293 Mich. App. at 439. 43. Id. at 444-45. 44. Id. at 444 (emphasis in original).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

917

objective basis for [the plaintiff] to be restricted in any way based on her examination of the plaintiff and review of diagnostic testing.45 B. No-Fault 1. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3107 Allowable Expenses The Michigan Court of Appeals continues to provide direction as to permissible consideration for determining reasonableness of provider charges in what appears to be an attempt to reduce steeply rising provider charges in the no-fault field to costs similar to areas such as workers compensation and Medicare/Medicaid approved costs. In Hardrick v. Auto Club Insurance Association (ACIA),46 the Michigan Court of Appeals addressed parameters of reasonableness for provider charges given the continuous rise in related suits.47 The court of appeals vacated the jury verdict and remanded the case for a new trial due to the trial courts abuse of discretion in imposing unjust sanctions against ACIA.48 The significant issue was whether agency rates were relevant to a jurys determination of reasonableness regarding the cost of family-provided care.49 The parties disputed the reasonableness of the family-provided attendant-care services valuation prescribed by the plaintiffs psychiatrist.50 The court of appeals held that the market rate for agency-provided attendant-care is relevant51 to determine a rate for family provided services.52 Because no-fault insurers customarily pay

45. Id. (noting the trier of fact may not have accepted Dr. DeSantiss findings; however, a question of fact remained that could not be decided as a matter of law). 46. 294 Mich. App. 651; 819 N.W.2d 28 (2011) appeal denied, 493 Mich. 867; 821 N.W.2d 542 (2012). 47. Id. 48. Id. at 655. The trial court found that ACIA had violated its discovery orders and precluded it from presenting any witnesses or testimony at trial. Id. Thus, ACIA was limited only to cross-examining the plaintiffs witnesses and challenging his experts evidence as to the reasonableness of attendant-care services provided by his family members. Id. at 657. The court of appeals reasoned that the sanction was disproportionate and affected the entirety of the trial. Id. at 664. 49. Id. at 679-80. 50. Id. at 664. ACIA never disputed the amount of hours. Id. at 656. Instead, ACIA classified the plaintiffs parents as home health aides instead of behavioral technicians. Id. 51. Id. at 666-67 (reasoning MRE 401 provides that relevant evidence is evidence having any tendency to make the existence of any fact that is of consequence to the determination of the action more probable or less probable than it would be without the evidence.) (emphasis original). 52. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App. at 665-66 (reasoning that Bonkowski v. Allstate Ins. Co., 281 Mich. App. 154; 761 N.W.2d 784 (2008) does not bind the court because

918

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

agency rates for attendant-care services, the agency rate charged for care provided by a behavioral technician relates to a consequential fact53 and is a piece of evidence that throws some light, however faint, on the reasonableness of a charge for attendant-care services.54 The court of appeals rejected the dissents contention that market rates55 determine what a reasonable charge is under the No-Fault Act.56 The court found no reference to the term market rate in either the No-Fault Act or the immense amount of no-fault case law.57 The court also found the dissents wage-based approach to be inconsistent with the language of the No-Fault Act comparing the scenario to that of reasonable attorney fees.58 The Hardrick court rationalized that prior nofault decisions demonstrated an effort to circumscribe a fact-finders reasonable-charge determination.59 These cases rejected a customary fee by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) as constituting a

Bonkowski acknowledged that its analysis relating to agency rates for attendant care is pure dicta and has no precedent over the court). Bonkowski also implies that it questioned the conclusion reached in Manley v. Detroit Automobile Inter-Insurance Exchange, 127 Mich. App. 444, 455; 339 N.W.2d 205 (1983). However, the court did not address this issue as the defendant did not argue the accuracy of the Manley decision. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App. at 665-66. The Hardrick court disagreed with the Bonkowski ruling that agency rates [were] irrelevant to establish family-care rates. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App. at 666. 53. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App. at 668-69 (citing People v. Crawford, 458 Mich. 376, 390; 582 N.W.2d 785 (1996) (The threshold is minimal: any tendency is sufficient probative force.)). The court of appeals also cited the Michigan Supreme Courts holding in People v. Brooks: It is enough if the item could reasonably show that a fact is slightly more probable than it would appear without that evidence. Even after the probative force of the evidence is spent, the proposition for which it is offered still can seem quite improbable. Thus, the common objection that the inference for which the fact is offered does not necessarily follow is untenable. It poses a standard of conclusiveness that very few single items of circumstantial evidence ever could meet. A brick is not a wall. People v. Brooks, 453 Mich. 511, 519; 557 N.W.2d 106 (1996) (citing CHARLES T. MCCORMICK, 185 MCCORMICK ON EVIDENCE 776 (4th ed. 1992)). 54. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App at 669 (citing Beaubien v. Cicotte, 12 Mich. 459, 484 (1864)). 55. Id. at 691 (Markey, J., dissenting) (defining market rates as either what an individual care provider would be paid or what a health-care agency might pay an independent contractor to provide similar services.). 56. Id. at 670. 57. Id. 58. Id. at 671, 673-74 (citing Smith v. Khouri, 481 Mich. 519, 528; 751 N.W.2d 472 (2008)). 59. Id. at 674.

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

919

reasonable charge60 and found the amount paid by Medicare, Medicaid, workers compensation insurers and BCBSM inadmissible to prove reasonableness.61 The court of appeals viewed the reasonableness inquiry as encompassing any evidence bearing on fair compensation for the particular services rendered, which it determined included evidence of an employees hourly wage.62 In addition, the court decided that evidence of overhead and opportunity costs should be considered in calculating a reasonable charge.63 In Bronson Methodist Hospital. v. Home-Owners Insurance Co.,64 the Michigan Court of Appeals continued to follow Hardrick,65 and provided additional parameters of reasonableness for provider charges.66 The court of appeals reversed summary disposition entered in favor of the plaintiff provider, which it found to be prematurely granted.67 This consolidated appeal arose from disputed charges for surgical implant products provided to defendants insureds after auto-accidents.68 The insurers requested invoices demonstrating the cost to the provider for the surgical implants.69 However, the plaintiff provider refused to offer this information, and the insurer refused to pay for the charges relying on the statutory provision.70 The insurer filed a motion to compel this information after the suit was filed, and the provider filed a motion for summary disposition.71 The trial court determined that the plaintiff was

60. Hardrick, 294 Mich. App. at 674 (citing Hofmann v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 211 Mich. App. 55, 113; 535 N.W.2d 529 (1995)). 61. Id. at 675 (citing Mercy Mt. Clemens Corp. v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 219 Mich. App. 46, 54-55; 555 N.W.2d 871 (1996)). 62. Id. at 675-76. 63. Id. at 676 (citing Sharp v. Preferred Risk Mut. Ins. Co., 142 Mich. App. 499, 51315; 370 N.W.2d 619 (1985); Mira v. Nuclear Measurements Corp., 107 F.3d 466, 472 (7th Cir. 1997)). The court of appeals compared this scenario to the workers compensation case Sokolek v. General Motors Corp., 450 Mich. 133, 145; 538 N.W.2d 369 (1995), noting [m]any considerations may be necessary to make such a determination. Id. 64. 295 Mich. App. 431; 814 N.W.2d 670 (2012). 65. Id. at 651. 66. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. 431, 434; 814 N.W.2d 670, appeal denied, 493 Mich. 880; 821 N.W.2d 784 (2012). 67. Id. 68. Id. at 434-35 (noting the insurers timely paid the portions of plaintiffs bills for all charges other than for the surgical implant products utilized to treat both the insureds). 69. Id. at 435. 70. Id. 71. Id. 437-38 (stating the provider maintained that the insurer attempted to use the discovery process to obtain confidential and proprietary information when defendants are

920

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

not required to provide the cost of surgical implant products, denied the insurers discovery request, and afforded the defendant an opportunity to amend its answer to include a claim that the providers charges were unreasonable.72 After providing payment for reasonable surgical implant charges, the plaintiff again moved for summary disposition, arguing the defendants methods for determining the reasonableness of the charges was improper as a matter of law under MCR 2.116(C)(10) and the only relevant consideration under the No-Fault Act is the providers charges for medical services.73 The trial court granted summary disposition in favor of the plaintiff, including penalty interest, and the insurers appealed.74 The plaintiff appealed the trial courts denial of attorney fees, which is addressed infra at Section II.B.4.75 Continuing the trend of finding the provider holds the burden of proof to justify the amounts charged to no-fault insurers, the court of appeals held summary disposition improper because a factual dispute remained as to the reasonableness of the plaintiffs hospital bills charged to the defendants.76 No-fault insurers are required under the Act to investigate the reasonableness of charges that providers submit, as clearly set forth in MCLA Section 500.3107.77 The court reasoned the plain and ordinary language of [Section] 3107 requiring no-fault insurance carriers to pay no more than reasonable medical expenses, clearly evinces the Legislatures intent to place a check on health care providers who have no incentive to keep the doctor bill at a minimum.78 The court of appeals held the actual cost to the hospital for surgical implant products is discoverable, relevant and admissible to

required to fully process the plaintiffs submittal of charges, and the insurer could only request information related to the cost of treatment to the injured person, not the cost to the provider for providing the treatment.). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3158(2) (West 2012). 72. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. at 439. Given the trial courts ruling, the insurer, through an audit consultant, determined an estimated cost for the surgical implant products utilized and provided payment, which it believed to be reasonable charges for those products. Id. 73. Id. at 440. 74. Id. 75. See infra Section II.B.4. 76. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. at 454-55 (citing U.S. Fid. Ins. & Guar. Co. v. Mich. Catastrophic Claims Assn, 484 Mich. 1, 18; 795 N.W.2d 101 (2009); Hofmann v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 211 Mich. App. 55, 93-94; 535 N.W.2d 529 (1995)). 77. Id. at 448 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3107 (West 2012); Advocacy Org. for Patients & Providers (AOPP) v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 257 Mich. App. 365, 383; 670 NW2d 569 (2003)). 78. Id. (quoting AOPP, 257 Mich. App. at 377-78).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

921

determine the reasonable cost for the product, as it is part of a collage of factors affecting the reasonable rate of a providers charges.79 To do otherwise, would abrogate the cost-policing function of no-fault insurers, contrary to the intention of the Legislature.80 However, the court of appeals cautioned that its ruling is limited to standalone items that may be definitely quantified, recognizing access to a providers cost information could open the door to nearly unlimited inquiry into the business operations of a provider, including into such concerns as employee wages and benefits. 81 The Bronson courts holding only applies to similar types of costs for durable medical-supply products . . . which are billed separately and distinctly from other treatment services and which . . . require little or no handling or storage by a provider.82 2. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3114 Priority of Insurers In Grange Insurance Co. of Michigan v. Lawrence, the Michigan Court of Appeals determined that a child is a resident relative of both parents and each parents insurer is equally liable for the minor childs PIP benefits.83 In this case, the parents shared joint legal custody, but the mother held primary physical custody.84 The court of appeals considered prior Michigan Supreme Court decisions Workman v. Detroit Automobile Inter-Insurance Exchange85 and Dairyland Insurance Co. v. Auto-

79. Id. at 452-54 (quoting Hardick, 294 Mich. App. 651, 678; 819 N.W.2d 28 (2011)). 80. Id. at 449-50 (To limit assessing the reasonableness of provider charges solely to a comparison of such charges among similar providers would be to leave the determination of reasonableness solely in the hands of the providers.). 81. Id. at 451. 82. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. at 451. 83. Grange Insurance Co. of Mich. v. Lawrence., 296 Mich. App. 319, 324; 819 N.W.2d 580 (2012), appeal granted, 493 Mich. 851; 820 N.W.2d 504 (2012). 84. Id. at 321 (emphasis added). 85. 404 Mich. 477; 274 N.W.2d 373 (1979). The Workman court articulated a four factor test to determine whether one is domiciled in the same household: (1) [T]he subjective or declared intent of the person of remaining, either permanently or for an indefinite or unlimited length of time, in the place he contends is his domicile or household; (2) the formality or informality of the relationship between the person and the members of the household; (3) whether the place where the person lives is in the same house, within the same curtilage or upon the same premises; (4) the existence of another place of lodging by the person alleging residence or domicile in the household. Workman, 404 Mich. at 496-97 (citations omitted).

922

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

Owners Insurance Co.,86 which set forth factors for determining whether a minor child is domiciled with a particular parent.87 The court found nothing in MCLA Section 500.3114(1), Workman, or Dairyland that limited a minor child of divorced parents to one domicile.88 There is also no requirement that domicile be defined as a principal residence.89 In this case, the court of appeals found that the minor child was domiciled with both parents for the following reasons: With regard to the Workman factors: (1) there was no evidence of an intention to change the parenting arrangement; (2) the same formal relationship existed between [the minor child], Josalyn, and her two parents; (3) at both homes, Josalyn lived in the house; and (4) as to both homes, Josalyn had another place at which she stayed. With regard to the Dairyland factors: (1) what little mail Josalyn received came to [her mother] Rosinskis home, (2) Josalyn had possessions at both homes, (3) Josalyn primarily used Rosinskis address, (4) Josalyn had a room at both homes, and (5) Josalyn was dependent on both parents for support.90 The court of appeals affirmed the trial courts ruling that Grange Insurance pay for fifty percent of the benefits Farm Bureau previously paid for personal protection benefits.91 In Corwin v. DaimlerChrysler Insurance Co.,92 the court of appeals found that the insurance policy at issue violated the intent of the NoFault Act because it attempted to shift the primary liability for no-fault coverage by reforming the contract so the injured parties became named insureds.93 John Corwin leased the vehicle from Chrysler LLC, who did

86. 123 Mich. App. 675; 333 N.W.2d 322 (1983). The Dairyland court found additional factors particularly helpful for a minor child: Other relevant indicia of domicile include such factors as whether the claimant continues to use his parents home as his mailing address, whether he maintains some possessions with his parents, whether he uses his parents address on his drivers license or other documents, whether a room is maintained for the claimant at the parents home, and whether the claimant is dependent upon the parents for support. Dairyland, 123 Mich. App. at 682. 87. Grange, 296 Mich. App. at 323-24. 88. Id. 89. Id. 90. Id. 91. Id. at 324-25. 92. 296 Mich. App. 242; 819 N.W.2d 68 (2012). 93. Id.

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

923

not give Corwin an option to purchase insurance with another automobile insurer other than DaimlerChrysler Insurance Company (Chrysler Insurance).94 Following an auto accident, a priority dispute involving the injured plaintiffs, John and Vera-Anne Corwin, arose between personal automobile insurance policies for their other vehicles and Chrysler Insurance.95 The Chrysler Corporation and its United States subsidiaries were the named insureds, not the Corwins.96 Under the Chrysler Insurance policy for personal injury protection, benefits may not be paid to anyone entitled to Michigan no-fault benefits as a Named Insured under another policy . . . .97 The Corwins and Auto Club Insurance Association, the insurer of the Corwins no-fault policy for a different vehicle, brought suit against Chrysler Insurance, Foremost Insurance (the insurer of the plaintiffs motor home), and Jackson (the atfault driver) for declaratory judgments regarding the different insurers obligations to pay PIP benefits and the Corwins right to uninsuredmotorist coverage.98 The trial court granted summary disposition to Chrysler Insurance and ordered Foremost Insurance to pay half of the PIP benefits.99 On appeal, Auto Club and Foremost contended that the Chrysler Insurance policy violated public policy under the No-Fault Act and needed reformation.100 The court of appeals held that the lessor and its subsidiaries were not owners or registrants of the [vehicle], did not maintain, operate, or use the [vehicle], and residual liability and property protection coverage did not apply.101 Instead, Chrysler LLC and its United States subsidiaries did not derive any kind of benefit from [a] thing so insured nor [did] they suffer any kind of loss that would be suffered by its damage or destruction.102 Because Chrysler LLC and its United States subsidiaries [did] not have an insurable interest as the named insured in the Chrysler Insurance policy, the policy violates public policy and was void, meaning the owner, Mr. Corwin, violated his statutory duty to maintain security for the payment of No-Fault benefits.103 Thus, the court of appeals held that the Chrysler Insurance

94. Id. at 248. 95. Id. at 247. 96. Id. at 248-49. 97. Id. at 249. 98. Corwin, 296 Mich. App. at 250. 99. Id. at 252. 100. Id. at 253. 101. Id. at 259-60. 102. Id. at 260 (citing Morrison v. Secura Ins., 286 Mich. App. 569, 573; 781 N.W.2d 151 (2009)). 103. Id.

924

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

policy needed to be reformed to comply with public policy so as to not allow the insurer to improperly shift a statutory responsibility for providing no-fault coverage.104 In addition, the Corwin court found that the Chrysler Insurance policy contravened the Legislatures intent of the No-Fault Act, specifically MCLA Sections 500.3114 and 500.3115, because it enabled the insurer to avoid primary liability for PIP benefits payable to insured, injured persons.105 Mr. Corwin owned the vehicle because he leased it for more than thirty days and the insurance premium was deducted from Mr. Corwins monthly lease payment.106 Therefore, under the No-Fault Act, the Chrysler Insurance policy provided no-fault insurance to the Corwin household.107 Because of this, the court of appeals reasoned the fact that Chrysler LLC and its United States subsidiaries were named insureds meant there was a coordination-ofbenefits clause in disguise, which is contrary to the legislative intent that an injured persons personal insurer stand primarily liable for PIP benefits.108 As such, the Corwin court determined that the Chrysler Insurance policy had to be reformed to include both Corwins as named insureds.109 In analyzing whether Chrysler Insurance was responsible for paying any PIP benefits, the court of appeals applied MCLA Section 500.3114(1) and Detroit Auto Inter-Ins. Exchange (DAIIE) v. Home Insurance Co.,110 which held that DAIIE and Home Insurance Company possessed equal priority because they both issued policies that named the insured.111 Thus, the court of appeals held that Auto Club, Foremost, and Chrysler Insurance assumed equal priority for Mr. Corwins PIP benefits because all the policies listed him as a named insured.112 The court noted that Auto-Club and Chrysler Insurance were responsible for Mrs. Corwins PIP benefits, as the Foremost policy did not list her as a named insured pursuant to MCLA Section 500.3114(1).113

104. Corwin, 296 Mich. App. at 260 (citing Morrison, 286 Mich. App. at 572 and State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Enter. Leasing Co., 452 Mich. 25, 40-41; 549 N.W.2d 345 (1996)). 105. Id. at 262. 106. Id. at 262-63 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3101(2)(h)(i) (West 2008)). 107. Id. at 263 (citing Farmers Ins. Exch. v. AAA of Mich., 256 Mich. App. 691, 697; 671 N.W.2d 89 (2003)). 108. Id. (citations omitted). 109. Id. at 264. 110. 428 Mich. 43, 47-48; 405 N.W.2d 85 (1987). 111. Corwin, 296 Mich. App. at 266 (citing Detroit Auto. Inter-Ins. Exch., 428 Mich. at 47-48). 112. Id. at 267. 113. Id. at 267 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3114(1) (West 2002)).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

925

3. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 500.3142 Overdue Benefits In Karmol v. Encompass Property and Casualty Co., the Michigan Court of Appeals held that the no-fault insurer did not delay paying personal protection benefits warranting penalty interest and attorney fees when an ERISA health care plan previously paid the insureds medical expenses.114 The court of appeals reasoned that Michigan law provides that a claimant incurs an expense when she becomes liable for the cost,an out of pocket expense or signing a contract for products or services.115 If benefits are not paid in a timely manner as set forth under MCLA Section 500.3142(3), interest begins to accumulate and attorney fees are recoverable under MCLA Section 500.3148(1).116 At the time of filing suit against her no-fault insurer, the plaintiff did not have any unpaid medical bills, [she] had never been exposed to personal liability for the costs of her sons care, and no evidence suggested a delay in payment for any bills.117 The fact that an ERISA plan rather than a nofault insurer initially paid the medical bills did not demonstrate any delay in payment of benefits.118 The court of appeals found no evidence to demonstrate any delay in paying PIP benefits and reversed and remanded the case for entry of judgment in favor of the insurer.119 4. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. Section 3148 Attorney Fees In Bronson Methodist Hospital v. Auto-Owners Insurance Co., the Michigan Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts denial of attorney fees to the plaintiff because there was no evidence that the insurer unreasonably withheld benefits under MCLA Section 500.3148(1).120 The court of appeals reasoned that the insurer has the burden of justifying its refusal or delay to promptly pay personal protection insurance benefits.121 The insurer contended that its refusal to pay the full amount of the plaintiffs charges for surgical implants was based on a legitimate question of statutory construction and factual uncertainty regarding the reasonableness of those charges, and the trial court found

114. 293 Mich. App. 382, 384; 809 N.W.2d 631 (2011), appeal denied, 491 Mich. 885; 809 N.W.2d 580 (2012). 115. Id. at 389-90. 116. Id. at 390. 117. Id. at 391. 118. Id. 119. Id. at 392. 120. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. at 454, 456 (citing Moore v. Secura Ins., 482 Mich. 507, 517; 759 N.W.2d 833 (2008)). 121. Id. (citing Ross v. Auto Club Grp., 481 Mich. 1, 11; 748 N.W.2d 552 (2008)).

926

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

the refusal proper under the circumstances of the case.122 The court of appeals reasserted that insurers have a duty under the No-Fault Act123 to audit and challenge the reasonableness of a providers charges submitted to the insurer for payment.124 The court of appeals found an absence of case law construing MCLA Section 500.3158(2), requiring a provider to deliver a written report of the . . . costs of treatment of the injured person and produce forthwith and permit inspection and copying of its records regarding costs of treatment.125 The court of appeals decided that the insurers payment for only the undisputed portions of the bills was reasonable under these circumstances, even if it was later determined that the insurer was obligated to pay those charges.126 In sum, the court found that the attorney-fee penalty provision of the No-Fault Act is not triggered when the insurer requests written documentation regarding the cost of treatmenta providers charges for surgical implantsand provides only partial payment when no documentation is produced by the provider.127 In Gentris v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., the Michigan Court of Appeals vacated the trial courts order denying attorney fees and taxable costs.128 The insurer contended it was entitled to attorney fees under MCLA Section 500.3148(2).129 The trial court denied attorney fees because it found no dispute that [the plaintiff] was injured and in need of attendant-care services.130 The trial court also denied the insurers request for taxable costs pursuant to MCR 2.625(G) finding State Farm did not comply with the technical requirements of the court rule.131 The court of appeals found that the trial court abused its discretion in denying State Farms request for attorney fees because the insureds claim for the benefits at issue could

122. Id. at 457. 123. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3107 (West 2012). 124. Bronson Methodist Hosp., 295 Mich. App. at 457 (citing AOPP, 257 Mich. App. at 378, affd, 472 Mich. 91; 693 N.W.2d 358 (2005)). 125. Id. at 458. 126. Id. 127. Id. 128. Gentris v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 297 Mich. App. 354, 361-64; 824 N.W.2d 609 (2012) (noting the jury trial for attendant care services under the No-Fault Act resulted in a no-cause verdict in favor of the insurer, which involved the alleged underpayment and/or nonpayment of attendant care benefits). 129. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3148(2) (West 2012) (providing in pertinent part, [a]n insurer may be allowed by a court an award of reasonable sum against a claimant as an attorneys fee for the insurers attorney in defense against a claim that was in some respect fraudulent or so excessive as to have no reasonable foundation.). 130. Gentris, 297 Mich. App. at 358. 131. Id.

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

927

have been deemed somewhat fraudulent or so excessive to have had no reasonable foundation regardless of the fact that the severity of the insureds injury was not in dispute.132 The court remanded this issue for further proceeding by the trial court.133 As to the request for taxable costs, the court of appeals found that State Farm provided lists and an affidavit by State Farms lead attorney, which satisfied the court rule.134 Thus, the court of appeals directed the trial court to enter an award of taxable costs in favor of State Farm, except for any costs lined out as required or classified as witness fees under MCR 2.625(G)(3).135 C. Additional Cases from the Michigan Court of Appeals In State Treasurer v. Snyder, the court of appeals considered whether a life insurance policy beneficiary may disclaim his interest, after depositing the proceeds of the policy into his prison account, because he knew the insurance proceeds would apply for reimbursement of the costs associated with his incarceration under the State Correctional Facility Reimbursement Act (SCFRA).136 The defendant argued that the insurance proceeds from his mothers insurance policy were not his assets under MCLA Section 800.401a(a) because he disclaimed his interest under the Disclaimer of Property Interest Law (DPIL).137 The court of appeals reasoned that the legislature enacted the SCFRA with the intent to allow recovery of the cost of prison incarceration by seeking and securing assets through all legal means necessary.138 The court found that defendant attempted to avoid his statutory duty under the SCFRA and frustrate the States statutory right to partial reimbursement of incarceration costs, which violates legislative intent.139 The court also reasoned that the SCFRA did not provide a right to disclaim an interest

132. Id. at 363. 133. Id. 134. Id. at 364. See MICH. CT. R. 2.625(G)(1)-(2) (providing in pertinent part, (1) [e]ach item claimed in the bill of costs, except fees of officers for services rendered, must be specified particularily; (2) [t]he bill of costs must be verified and must contain a statement that (a) each item of cost or disbursement claimed is correct and has been necessarily incurred in the action, and (b) the services for which fees have been charged were actually performed). 135. Gentris, 297 Mich. App. at 367. 136. State Treasurer v. Snyder, 294 Mich. App. 641, 643-44; 823 N.W.2d 284 (2011). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 800.404(1) (West 1984). 137. Snyder, 294 Mich. App. at 646 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 800.401a(a) and 700.2902(1) (West 2004)). 138. Id. at 647. 139. Id. at 648 (citing State Treasurer v. Sheko, 218 Mich. App. 185, 189; 553 N.W.2d 654 (1996)).

928

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

in a potential asset to seek reimbursement only after the prisoner accepted an asset.140 In sum, the court held that the SCFRA barred a prisoner from disclaiming insurance proceeds.141 In People v. Allen, the court of appeals affirmed the trial courts holding that the insurer suffered a loss due to the defendants criminal conduct, which entitled the insurer to restitution under the Crime Victims Rights Act.142 The defendant attempted to purchase a controlled substance from a pharmacy using a fraudulent prescription and private information from her employers, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, subscriber.143 The court of appeals found financial harm to the insurer because, Burnett, an employee, maintained numerous other claims open for investigation, but instead spent forty-four hours investigating the defendants fraud.144 The loss was not Burnetts salary or the fraud departments budget, but the loss of time measured by the value of hours spent on the investigation.145 In White v. State Farm Fire and Casualty Co., the Michigan Court of Appeals addressed the issue of whether a MCLA Section 500.2833(1)(m) appraiser who receives a contingency fee is independent as set forth under the Statute.146 The insurer refused to accept appraiser Moss as an independent appraiser because he was not disinterested under its policy; he stood to receive ten percent of any amount recovered.147 The parties filed cross-motions for summary disposition and the trial court found Moss competent and independent as required under MCLA Section 500.2833(1).148 Under the current version of the statute, there is no requirement that the appraiser be impartial or disinterested.149 The court of appeals applied its prior decision in Auto-Owners Insurance Co. v. Allied Adjusters & Appraisers, Inc.,150 which held that an independent appraiser may be biased toward the party who hires and pays him, as long as he retains the ability to base his recommendation on his own

140. Id. at 648-49. 141. Id. at 650. 142. People v. Allen, 295 Mich. App. 277, 280; 813 N.W.2d 806 (2011). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 780.766(2) (West 2009). 143. Allen, 295 Mich. App. at 279. 144. Id. at 282-83. 145. Id. 146. 293 Mich. App. 419, 422; 809 N.W.2d 637 (2011). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.2833(1)(m) (West 1990). 147. White, 293 Mich. App. at 424. 148. Id. at 422. 149. Id. at 424. 150. 238 Mich. App. 394; 605 N.W.2d 685 (1999).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

929

judgment.151 With no published opinions on point, the court of appeals looked to other jurisdictions and followed Rois v. Tri-State Insurance Co.152 The court of appeals held that a contingency-fee agreement does not prevent an appraiser from being independent and found no evidence that Moss was subject to control, restriction, modification, or limitation by anyone involved.153 III. DECISIONS OF THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT In DeFrain v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. the Michigan Supreme Court overruled Bradley v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co.,154 in holding that an unambiguous notice-ofclaim provision in an [uninsured motorist] policy is enforceable without a showing that the failure to comply prejudiced the insurer.155 The Michigan Supreme Court reversed and remanded the decision because the court of appeals improperly applied Koski v. Allstate Insurance Co.156 In DeFrain, the insurer did not receive notice until eighty-six-days after the hit-and-run accident.157 The injured party filed suit after State Farm denied the claim for uninsured motorist benefits because it did not receive timely notice, which the policy provided as a condition precedent.158 Relying on Bradley, the court of appeals indicated that State Farm failed to demonstrate that it suffered prejudice because of the claimants failure to provide timely notice.159 The supreme court granted leave to appeal to provide clarification to contract interpretation, specifically the uninsured motorist policy provisions at issue.160 The supreme court held that its prior application of Jackson v.

151. White, 293 Mich. App. at 425 (citing Auto-Owners Ins. Co., 238 Mich. App. at 401). 152. Id. at 428. See Rois v. Tri-State Ins. Co., 714 So.2d 547 (Fla. App. 1998). 153. White, 293 Mich. App. at 428-30 (rejecting the insurers argument that allowing Moss to serve as an appraiser was a violation of its due-process rights). The court found appraisers to be more similar to attorneys than to judges or umpires and that Moss was not required to be quasi-judicial or impartial. Id. at 429-30. 154. 290 Mich. App. 156; 810 N.W.2d 386 (2010), overruled by DeFrain v. State Farm Auto. Ins. Co., 491 Mich. 359; 817 N.W.2d 504 (2012). 155. DeFrain v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 491 Mich. 359, 376; 817 N.W.2d 504 (2012). See also Jackson v. State Farm Mut. Aut. Ins. Co., 472 Mich. 942; 698 N.W.2d 400 (2005); Rory v. Contl Ins. Co., 473 Mich. 457; 703 N.W.2d 23 (2005). 156. DeFrain, 491 Mich. at 362. See Koski, 456 Mich. 439; 572 N.W.2d 636 (1998). 157. DeFrain, 491 Mich. at 363. 158. Id. at 362. 159. Id. at 366. See Bradley v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co, 290 Mich. App. 156; 810 N.W.2d 385 (2010), overruled by DeFrain v. State Farm Auto. Ins. Co., 491 Mich. 359; 817 N.W.2d 504 (2012). 160. DeFrain, 491 Mich. at 366-67.

930

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co.161 rendered the unambiguous notice-of-claim provision enforceable without a showing that the failure to comply with the provision would prejudice the insurer.162 The DeFrain court rejected the contention that enforcing a 30-day notice provision would violate MCL Section 500.3008 because the plaintiff failed to demonstrate that it was not reasonably possible to give such notice within the thirty-day requirement.163 In Krohn v. Home-Owners Insurance Co., the Michigan Supreme Court held that experimental medical procedures are not reasonably necessary as defined under the No-Fault Act and are not covered without objective and verifiable medical evidence relating to their effectiveness.164 The plaintiff suffered a spinal fracture leaving him a paraplegic and sought PIP benefits related to an experimental surgical procedure performed in Portugal, which the FDA did not approve.165 The plaintiff discussed the procedure with his treating physician, who did not endorse or recommend the procedure, and informed plaintiff that because it was not part of standard clinical care, it was not likely to be covered by insurance.166 The plaintiff also met with a patient who underwent this procedure and claimed he was able to stand and walk on a device.167 The insurer paid for all the postsurgical physical therapy treatment.168 The plaintiff testified that he noticed improvements immediately after the procedure.169 This suit was filed to recover travel expenses to and from Portugal and surgical costs.170

161. Jackson, 472 Mich. at 942. 162. DeFrain, 491 Mich. at 368-71 (citing Mullins v. St. Joseph Mercy Hosp., 480 Mich. 948; 741 N.W.2d 300 (2007)). 163. Id. at 374. See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3008 (West 2012) (requiring liability insurance policies to provide that failure to comply with notice requirements shall not invalidate any claim made by the insured if it shall be shown not to have been reasonably possible to give such notice within the prescribed time and that notice was given as soon as was reasonably possible.). 164. Krohn v. Home-Owners Ins. Co., 490 Mich. 145, 148; 802 N.W.2d 281 (2011). 165. Id. at 147, 149. The Olfactory Ensheathing Glial Cell Transplantation procedure involves transplanting tissue from behind the patients sinus cavities, which contains stem cells, to the injury site with the possibility that the transplanted stem cells could develop into spinal cord nerves. Id. at 149. There was insufficient existing research for clinical trials for FDA evaluation and no one had yet applied for FDA approval of the procedure. Id. 166. Id. at 150. 167. Id. 168. Id. at 151. 169. Id. (noting the plaintiff testified that he could sometimes move his legs, crawl forward and backward, and control bowel and bladder movements, resulting in fewer urinary tract infections.). 170. Krohn, 490 Mich. at 151.

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

931

The plaintiffs doctor, Dr. Hinderer, testified that it was possible that the improvements were the sole result of vigorous physical therapy after the surgery.171 Dr. Hinderer would not conclude that the minor improvements resulted from the surgical procedure.172 Dr. Lima, a member of the neurological team in Portugal, contended that this procedure provides functional recovery of neurons, but did not testify to the efficaciousness of the procedure.173 Dr. Lima testified that this procedure was reasonably necessary for the plaintiff because there were no other treatment options available for his injury.174 The defendant moved for a directed verdict; however, the trial court denied the motion finding the determination of whether the experimental procedure was reasonably necessary was a question for the trier of fact.175 The jury found the procedure reasonably necessary and awarded allowable expenses, plus interest, case-evaluation sanctions, and taxable costs.176 The court of appeals reversed, holding that plaintiff was required to demonstrate that the procedure had gained general acceptance in the medical community.177 The plaintiff filed a leave to appeal, which the court granted in order to determine whether experimental procedures are an allowable expense under MCLA Section 500.3107(1)(a) of the No-Fault Act.178 Following precedent, the supreme court reasoned that MCLA Section 500.3107(1)(a) requires both reasonableness and necessity [as] explicit and necessary elements of a claimants recovery of no-fault benefits.179 The Nasser v. Auto Club Insurance Association court did not provide adequate guidance on how to determine the reasonableness of a necessary expense.180 However, the Krohn court concluded that experimental treatments are not necessarily barred from being compensable under the No-Fault Act, but require evidence that the

171. Id. 172. Id. 173. Id. 174. Id. at 153. 175. Id. at 154. 176. Krohn, 490 Mich. at 154. 177. Id. at 154, 187-88 (Hathaway, J., dissenting) (reasoning the issue was properly submitted to a jury). 178. Id. at 155. 179. Id. at 157 (citing Nasser v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 435 Mich. 33; 457 N.W.2d 637 (1990)). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3107(1)(a) (West 2012) ([A]n insurer is not liable for any medical expense . . . if the product or service itself is not reasonably necessary.) (emphasis in original). 180. Krohn, 490 Mich. at 158. See Nasser, 435 Mich. at 33.

932

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

procedure is reasonably necessary for plaintiffs care, recovery, or rehabilitation.181 In making its determination, the supreme court found no statutory language suggesting that reasonably should be determined on a subjective basis.182 Instead, the court held that an objective standard must be applied to determine whether the service or product was reasonably necessary.183 The supreme court further held that the plaintiff was required to present expert testimony that the experimental surgery may result in care, recovery or rehabilitation.184 In sum, the plaintiff must establish that the surgery is effective.185 In this case, the supreme court found that the plaintiff failed to meet the threshold for recovery because the expert testimony failed to establish whether the procedure performed was efficacious in plaintiffs care, recovery or rehabilitation.186 The supreme court rejected the dissents contention that its decision requires a medical necessity for coverage under the No-Fault Act.187 Instead, the court reiterated that it gave meaning to the clear language of MCLA Section 500.3107, which provides for products and services reasonably necessary . . . for an injured persons care, recovery, or rehabilitation.188 The Krohn decision does not preclude reimbursement for experimental medical treatment.189 However, the injured party holds a high standard to demonstrate that the treatment was reasonable and necessary under the No-Fault Act.190 In Frazier v. Allstate Insurance Co., the Michigan Supreme Court did not permit PIP benefits relating to a slip and fall on a patch of ice while the injured person closed the passenger door of her vehicle.191 In

181. Krohn, 490 Mich. at 158-59. 182. Id. at 163. 183. Id. at 161-62 (citing Allstate Ins. Co. v. McCarn, 471 Mich. 283, 289; 683 N.W.2d 656 (2004); Allstate Ins. Co. v. Freeman, 432 Mich. 656, 672; 443 N.W.2d 734 (1989), declined to follow by Fire Ins. Exch. v. Diehl, 450 Mich. 678; 545 N.W.2d 602 (1996)). 184. Id. at 163. The insured is not required to show that the experimental surgery gained general acceptance in the medical community before its reasonable necessity becomes a question for consideration by a trier of fact. Id. at 165. Expert testimony must be based on sufficient facts or data, the product of reliable principles and methods, and that the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case. Id. at 167. 185. Id. at 163-64. 186. Id. at 168. 187. Krohn, 490 Mich. at 171. 188. Id. at 172. 189. Id. at 164. 190. Id. 191. Frazier v. Allstate Ins. Co., 490 Mich. 381, 387; 808 N.W.2d 450 (2011).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

933

this case, the plaintiff placed a few personal items in the passenger compartment and fell when closing the passenger door.192 The Frazier court held that a door of an automobile is not considered equipment permanently mounted on the vehicle, which shed light on the meaning of alighting as defined in the parked vehicle portion of MCLA Section 500.3106(1).193 There was no dispute that the vehicle was parked and the plaintiff was required to meet one of the requirements set forth in MCLA Sections 500.3106(1)(b)-(c).194 The Frazier court reasoned that the plaintiff was not alighting from or entering her vehicle, so the exception to the exclusion from PIP benefit coverage for parked vehicles did not apply under MCLA Section 500.3106(1)(c) because before her injury, plaintiff had been standing with both feet planted firmly on the ground outside of the vehicle; she was entirely in control of her bodys movement, and she was in no way reliant upon the vehicle itself.195 The court determined that plaintiff already alighted the vehicle before she fell.196 The court refused to classify a door as equipment permanently mounted on [a] vehicle to provide for an exception to the exclusion of PIP coverage pursuant to MCLA Section 500.3106(1)(b).197 In Joseph v. Auto Club Insurance Association, the Michigan Supreme Court overturned its prior ruling in University of Michigan Regents v. Titan Insurance Co.198 relating to the application of the minor/insanity tolling provision199 to the one year back rule of the No192. Id. at 386 (stating the plaintiff placed a few personal items in the passenger compartment using the passenger door, stood up, and stepped out of the way of the door and fell when she closed the passenger door). 193. Id. 194. Id. at 386. 195. Id. at 385 (citing RANDOM HOUSE WEBSTERS COLLEGE DICTIONARY (2d ed.1997); NEW SHORTER OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY). See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3106(1)(b) (West 1987) (providing an exception when one is alighting from the vehicle, which is defined as to dismount from a horse, descend from a vehicle, etc. or to settle or stay after descending; come to rest.). 196. Frazier, 490 Mich. at 385-86. 197. Id. at 384-85. See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3106(1)(c) (West 1987) (requiring the equipment be mounted on a vehicle and indicates that the constituent parts of the vehicle itself are not equipment). 198. Joseph v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 491 Mich. 200, 213-14; 815 N.W.2d 412 (2012), overruling Univ. of Mich. Regents v. Titan Ins. Co., 487 Mich. 289; 791 N.W.2d 897 (2010), rehg denied, 815 N.W.2d 491 (Mich. 2012) (reasoning the Regents holding was erroneous because the clear statutory text of MCLA Sections 500.3145(1) and 600.5851(1) do not support this position). 199. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 600.5851(1) (West 2012) (providing in relevant part, if the person first entitled to make an entry or bring an action under this act is under 18 years of age or insane at the time the claim accrues, the person or those claiming under the person shall have 1 year after the disability is removed through death or otherwise, to

934

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

Fault Act.200 The supreme court reinstated its ruling in Cameron v. Auto Club Insurance Association,201 holding the minor/insanity tolling provision does not affect the one-year back rule.202 The Regents decision provided that a minor is required to bring suit before his nineteenth birthday and those classified as mentally incompetent/insane are required to bring suit no later than one year after the is was removed.203 The supreme court reasoned that the Regents Court contravened the legislative intent set forth in the clear language of MCLA Section 500.3145(1). 204 The Joseph case involved a claim brought thirty-two years after the accident for case-management services provided by the plaintiffs family members.205 Joseph was deemed insane for the past thirty-two years and requested application of the tolling provision of MCLA Section 500.3145.206 The supreme court found that the minority/insanity tolling provision . . . addresses only when an action may be brought, [but] does not preclude the application of the one-year-back rule, which separately limits the amount of benefits that can be recovered.207 The supreme

make the entry or bring the action although the period of limitations has run.). Notably, by its unambiguous terms, this provision concerns when a minor or person suffering from insanity may make the entry or bring the action, and the provision is entirely silent with regard to the amount of damages recoverable once an action has been brought. Id. 200. MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3145(1) (West 2012) (providing a claimant may not recover benefits for any portion of the loss incurred more than [one] year before the date on which suit is filed. This is separate from the one year statute of limitations found in the same Section of the No-Fault Act, which requires a suit for payment of outstanding PIP benefits to be filed no later than one year after the date of the accident causing the injury or one year after the most recent expenses or loss incurred). 201. 476 Mich. 55; 718 N.W.2d 784 (2006). 202. Joseph, 491 Mich. at 203-04. See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3154 (West 2012). 203. Regents, 487 Mich. at 302. See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 600.5851 (West 1994). 204. Joseph, 491 Mich. at 204 (citing Sun Valley Foods Co. v. Ward, 460 Mich. 230, 236; 596 N.W.2d 119 (1999)) (mandating the Michigan Supreme Court to follow the rules of statutory language to give effect to the Legislatures intent).The supreme court discussed the legislatures intent, providing: Although a no-fault action to recover PIP benefits may be filed more than one year after the accident and more than one year after a particular loss has been incurred (provided that notice of injury has been given to the insurer or the insurer has previously paid PIP benefits for the injury), 3145(1) nevertheless limits recovery in that action to those losses incurred within the one year preceding the filing of the action. Devillers v. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 473 Mich. 562, 574; 702 N.W.2d 539 (2005) (emphasis in original). 205. Joseph, 491 Mich. at 204. 206. Id. at 204-05 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3145 (West 2012)). 207. Id. at 203 (emphasis original).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

935

court addressed the doctrine of stare decisis, finding to allow the Regents decision to stand would result in a failure to enforce requirements under the statutes it professes to interpret.208 In Joseph, the supreme court limited recovery for losses incurred one year from the date of filing the plaintiffs complaint.209 As expected, Justice Marilyn Kelly issued a dissenting opinion, standing by her views as set forth in the Regents case.210 In Titan Insurance Co. v. Hyten, the supreme court overruled a line of Michigan cases which held that a party cannot show reasonable reliance on a representation if that party possesses the means to determine the inaccuracy of the representation.211 This case involved an applicant for an auto policy who failed to disclose that her drivers license was suspended at the time she submitted her application.212 The trial court and court of appeals held that the insurer could have easily ascertained this information by checking the record, and thus, estopped from raising the misrepresentation as a basis for rescission of the policy.213 The Titan court overruled Mable Cleary Trust v. EdwardMarlah Muzyl Trust214 to the extent it supported the proposition that a party has an independent duty to investigate and corroborate representations.215 The court also overruled the easily ascertainable rule216 set forth in State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co. v. Kurylowicz.217 Even though MCLA Section 500.3220(a) demonstrates an

208. Id. at 221 (citing Robinson v. Detroit, 462 Mich. 439, 468; 613 N.W.2d 307 (2000) (reasoning that overruling Regents allowed it to return the law, as is our duty, to what we believe the citizens of this state reading these statutes at the time of enactment would have understood [them] to mean.). 209. Id. 210. Id. at 223-26. 211. 491 Mich. 547, 550-51; 817 N.W.2d 562 (2012). 212. Id. at 551-52 (stating the plaintiffs drivers license was suspended when she signed the application for insurance with an expectation that her license was going to be reinstated within days; however, the plaintiffs license was not reinstated until almost a month later). 213. Id. at 551-53. 214. 262 Mich. App. 485; 686 N.W.2d 770 (2004), overruled by Titan Ins. Co. v. Hyten, 491 Mich. 547; 817 N.W.2d 562 (2012). 215. Titan, 491 Mich. at 555 n.4. 216. Id. at 564 (citing Ohio Farmers Ins. Co. v. Mich. Mut. Ins. Co., 179 Mich. App. 355; 455 N.W.2d 228 (1989), overruled by Titan Ins. Co. v. Hyten, 491 Mich. 547; 817 N.W.2d 562 (2012)) (providing that under the easily ascertainable rule, an insurer is not able to avail itself of traditional legal and equitable remedies to avoid liability under an insurance policy on the ground of fraud when that fraud could have been easily determined and the claimant is a third party). 217. 67 Mich. App. 568; 242 N.W.2d 530 (1976), overruled by Titan Ins. Co. v. Hyten, 491 Mich. 547; 817 N.W.2d 562 (2012).

936

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

intent to allow insurers a limited period to reassess the risk after formation of a policy, this principle does not preclude the insurer from pursuing traditional legal and equitable remedies when it does not elect to reassess the risk and later discovers fraud.218 The supreme court found no law to demonstrate a public policy that requires a business to maintain funds to benefit third parties with which it does not share a contractual relationship.219 The Titan court then reaffirmed the principles set forth in Keys v. Pace, holding an insurer is not precluded from availing itself of traditional legal and equitable remedies to avoid liability under an insurance policy on the ground of fraud in the application for insurance, even when the fraud was easily ascertainable and the claimant is a third party.220 An insurer does not have a duty to investigate or verify the representations of potential insureds.221 The appellate court remanded the case for a determination of whether the elements of actionable fraud had been satisfied.222 The Titan decision failed to address an issue related to establishing the fraud requirements.223 The supreme courts definition of fraud failed to recognize prior precedent that a misrepresentation need not be intentional to serve as the basis for rescinding an insurance policy, and there is no necessity to prove intent.224 In sum, the supreme court reinstated its holding in Keys and overruled the Michigan Court of Appeals holding in Kurylowicz.225

218. Titan, 491 Mich. at 566-67 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3220(a) (West 2009) (reasoning risk assessment and uncovering fraud are distinct processes and are not so logically interrelated that would suggest that addressing one would address the other). 219. Id. at 567 (citing Terrien v. Zwit, 467 Mich. 56, 66; 648 N.W.2d 602 (2002)). 220. Id. at 570 (citing Keys v. Pace, 358 Mich. 74; 99 N.W.2d 547 (1959)). 221. Id. at 569. See also Manier v. MIC Gen. Ins. Corp., 281 Mich. App. 485; 760 N.W.2d 293 (2008), overruled by Titan Ins. Co. v. Hyten, 491 Mich. 547; 817 N.W.2d 562 (2012); Hammoud v. Metro. Prop. & Cas. Ins. Co., 222 Mich. App. 485; 563 N.W.2d 716 (1997); United Sec. Ins. Co. v. Commr of Ins., 133 Mich. App. 38; 348 N.W.2d 34 (1984). 222. Titan, 491 Mich. at 572. 223. Id. 224. See U.S. Fid. & Guar. v. Black, 412 Mich. 99, 120; 313 N.W.2d 97 (1981); Lake States Ins. Co. v. Wilson, 231 Mich. App. 327, 331; 586 N.W.2d 113 (1998); Lash v. Allstate Ins. Co., 210 Mich. App. 98, 103; 532 N.W.2d 869 (1995); Legel v. Am. Cmty. Mut. Ins. Co., 201 Mich. App. 617, 618; 506 N.W.2d 530 (1993); THOMAS R. NEWMAN & BARRY R. OSTRANGER, HANDBOOK ON INSURANCE COVERAGE DISPUTES, 3.01(c) (16th ed. 2012). 225. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Kurlyowicz, 67 Mich. App. 568; 242 N.W.2d 530 (1976); Keys v. Pace, 358 Mich. 74; 99 N.W.2d 547 (1959).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW IV. DECISIONS OF THE U.S. DISTRICT COURTS

937

A. Cases Interpreting Michigan Law In Bajraszewski v. Allstate Insurance Co., the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan held that the No-Fault Act and Internal Revenue Code do not justify an insurers denial of attendant care payments if the injured party does not furnish the providers taxpayer identification number.226 Judge Lawson reasoned that [a]bsent a reporting obligation, the insured has no corresponding obligation to furnish taxpayer identification information because both Michigan and Federal law allow an insurance company to make payments directly to the insured.227 Thus, Barjraszewski provides that taxpayer identification information is not part of the reasonable proof necessary to set forth a claim for attendant care.228 In Auto Club Insurance Association v. Great American Insurance Group, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan also held that a drivers claim is not within the scope of the safe harbor exception to unlawfully taken vehicles.229 Here, the injured party was riding a dirt bike when he was struck by a Freightliner semi-truck insured by [the defendant].230 Unbeknownst to the plaintiff, Beuhrle approached him to purchase the dirt bike even though the bike was reported stolen weeks before.231 The injured party did not have a valid license at the time of the accident, and the dirt bike did not have a license plate.232 Because the injured party did not have available insurance, the plaintiff applied for PIP benefits through the Michigan Assigned Claims Facility (MACF).233 The plaintiff paid over $150,000 on behalf of the injured party and sought reimbursement for these payments from the defendant, alleging the defendant was the highest priority insurer according to the motorcycle provision of MCLA Section 500.3114(5).234

226. 825 F. Supp. 2d 873, 881 (2011). 227. Id. at 878-79 (citing 26 U.S.C.A. 6041(a)) (2006); MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3112 (West 2009)). 228. Id. at 881. 229. 800 F. Supp. 2d 877, 884-85 (E.D. Mich. 2011) (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3113 (West 1986)). 230. Id. at 878. 231. Id. at 878-79. 232. Id. at 879. 233. Id. 234. Id. (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3114(5) (West 2009)).

938

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911

District Court Judge Gerald Rosen held that the facts triggered an exclusion from insurance coverage as set forth in MCLA Section 500.3113(a), which provides in pertinent part: A person is not entitled to be paid personal protection insurance benefits for accidental bodily injury if at the time of the accident ... (a) The person was using a motor vehicle or motorcycle which he or she had taken unlawfully, unless the person reasonably believed that he or she was entitled to take and use the vehicle.235 According to the leading Michigan decision of Bronson Methodist Hospital v. Forshee,236 which provides guidance as to what MCLA Section 3113(a) means by taken unlawfully, the district court considered this case distinguishable and found the facts to be similar to those presented in Amerisure Insurance Co. v. Plumb.237 In Plumb, the owner of the dirt bike did not give permission or consent for anyone to use his motorcycle.238 Thus, the district court found that the injured party unlawfully took the dirt bike when the accident occurred.239 The issue then turned on whether the plaintiff established an exclusion from coverage under the safe harbor provision of MCLA Section 500.3113(a),240 which provided that the coverage exclusion does not apply if it is established that the injured party reasonably believe[s] that he or she is entitled to use the vehicle.241 The district court did not find this exclusion applicable because the injured party could not have believed he was entitled to use the dirt bike because he knew his

235. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 800 F. Supp. 2d at 879-80, 885 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3113(a) (West 1986)). 236. Id. at 880. See MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3113(a) (West 1986); Bronson Methodist Hosp. v. Forshee, 198 Mich. App. 617; 499 N.W.2d 423 (1993), overruled by Spectrum Health Hosps. v. Farm Bureau Mut. Ins. Co. of Mich., 492 Mich. 503; 821 N.W.2d 117 (2012). 237. Auto Club Ins. Assn, 800 F. Supp. 2d. at 882 (citing Amerisure Ins. Co. v. Plumb, 282 Mich. App. 417; 766 N.W.2d 878 (2009)). 238. Id. 239. Id. at 883-84 (citing Plumb, 282 Mich. App. at 428-29) (rejecting the plaintiffs argument that the injured party did not participate in a vehicle theft. However, the court again looked to Plumb and found that the injured party took possession and gained control, which [fit] comfortably within the ordinary definition of take.). 240. Id. at 884. 241. Id. (quoting MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3113(a) (West 1986)).

2012]

INSURANCE LAW

939

license had been suspended for several years, which violated MCLA Section 257.301(1).242 In Dugan v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan found that an insurer does not have a duty independent of the insurance policy to provide the insured with information related to what benefits she might be entitled under the No-Fault Act.243 The plaintiff argued that the defendant voluntarily assumed the duty of informing plaintiff of her benefits and provided only partial information about coverage and limited attendant care benefits, and failed to disclose all benefits available under the insurance policy.244 The court determined that the plaintiff did not pinpoint the basis for any assumed duty and thus failed to set forth the proper allegations to create a duty for her claim of negligence and silent fraud.245 Also, the district court did not find evidence to establish a claim for fraudulent concealment and equitable estoppel so as to prevent the application of the one-year-back limitation period under Michigan law.246 Lastly, the district court noted that it was highly unlikely plaintiff would be able to establish insanity under the statute, but did not grant defendants request to bar the claim for benefits outside the oneyear-back rule because an issue of fact remained regarding the allegations of insanity.247 B. Additional United States District Court Cases The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan determined whether there was coverage under a cemeterys insurance policy for the alleged misplacement of a body in Reed v. Netherlands Insurance Co.248 The Reeds alleged that insured, United Memorial Gardens Cemetery, misplaced their mothers remains.249 It was later determined that the body was not misplaced, and the burial took place as scheduled in the plot purchased by the plaintiffs.250 The plaintiffs did not

242. Id. at 885 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 257.301(1) (West 2011)). 243. 845 F. Supp.2d 803, 807-08 (E.D. Mich. 2012). 244. Id. at 807. 245. Id. at 807-08. 246. Id. at 808 (citing MICH. COMP. LAWS ANN. 500.3145(1) (West 2009)). 247. Id. at 808-09. 248. 860 F. Supp. 2d 407 (E.D. Mich. 2012). 249. Id. at 410. 250. Id. at 410-11. In fact, a clerical error reflected the mothers plot was sold to someone else at the time plaintiffs purportedly purchased it. Id. at 411. However, two other recordings demonstrated the actual burial of the mother in the correct plot: (1) the grounds superintendents paperwork and (2) the Cemeterys burial log book. Id.

940

THE WAYNE LAW REVIEW

[Vol. 58: 911