Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Legal Opinion - Contract Bulk Water - Sept. 27, 2013 Final

Hochgeladen von

Romulo UrciaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Legal Opinion - Contract Bulk Water - Sept. 27, 2013 Final

Hochgeladen von

Romulo UrciaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

September 27, 2013 Hon. Godofredo A.

Estupigan Municipal Hall of Majayjay, Majayjay, Laguna

Re

CONTRACT FOR THE SUPPLY OF BULK WATER DATED AUGUST 1, 2013 BETWEEN MUNICIPALITY OF MAJAYJAY AND ISRAEL BUILDERS AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION (IBDC)

Sir: This refers to your legal query of September 16, 2013 regarding the legality and validity of the above-stated Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water (subject contract for short) dated August 1, 2011. After thoroughly studying the subject contract and the circumstances/ conditions attending to its execution, we opined that the subject contract is inexistent and void from the beginning for reasons described below: 1. The subject contract did not comply with its attached condition.

The subject contract was executed pursuant to the Unsolicited Proposal of IBDC. In the Notice of Acceptance dated May 09, 2011 made by the former Municipal Mayor Teofilo B. Guera of the said Unsolicited Proposal, it is expressly stated therein that the acceptance of IBDCs Unsolicited Proposal is subject to the confirmation and approval of the Indicative Rate of return by the Investment Coordination Committee of the National Economic Development Authority (ICC-NEDA). A copy of the said Notice of Acceptance is hereto attached as Annex A.

However, after the execution of the subject contract, it was discovered that the Indicative Reasonable Rate of Return was not approved by ICC-NEDA because the subject contract and IBDCs Unsolicited Proposal were not received and approved by NEDA as shown in the attached Certifications both dated July 11, 2012 hereto attached as Annexes B and C, respectively. Since the subject contract was executed in violation of the condition provided in the Notice of Acceptance dated May 9, 2011, then it is quite clear that the subject contract is null and void as the consent to it by the Municipality of Majayjay was not produced by the concurrence of the offer and the acceptance. In other words, there is no consent to or acceptance of the Unsolicited Proposal of IBDC for failure of IBDC to comply with the condition prescribed in the said Notice of Acceptance. The Supreme Court has time and again declared that the contract is void when one of the essential requisites of a valid contract as provided for by Article 1318 of the Civil Code is totally wanting.1 The law on contracts provide that consent of the contracting parties is an essential requisite of a valid contract.2 Thus, the absence of consent of a contracting party renders the contract null and void.3 The rule is that if the consent of one of the contracting party is predicated upon the fulfillment of a condition, such condition shall first and foremost be fulfilled before the contracting party actually gives his consent to the contract. The fact that the Municipality of Majayjay gave a condition to IBDC before it (Municipality of Majayjay) can give its acceptance to the Unsolicited Proposal of IBDC, such conditional shall be fulfilled first before it can be said the Municipality of Majayjay has indeed accepted the Unsolicited Proposal of IBDC. In this case, however, IBDC failed to comply with the condition of the Municipality of Majayjay. 2. The subject contract is contrary to BOT Law. A. The PROJECT did not comply with the publication and approval requirement under Section 4 or R.A. No. 7718.

1 2

Francisco vs. Herrera, G.R. No. 139982. November 21, 2002. Article 1318 (1), Civil Code of the Philippines. 3 Spouses Guiang vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 125172, June 26, 1998

The subject contract states that Majayjay treated the Formal Proposal of IBDC as unsolicited proposal in accordance with the issued GUIDELINES on Joint Venture (JVs) pursuant to Section 8 (Joint Venture Agreements) of executive Order (EO) No. 423 dated April 30, 2005. But a closer look of the subject contract will show that the same was entered into pursuant to BOT Law as it involved an unsolicited proposal from IBDC involving important and priority project of Majayjay. The provisions of the BOT Law were never complied with in the execution of the subject contract. The subject matter of the subject contract is the Majayjay Water Project (PROJECT for short) involving the rehabilitation and improvement of Majayjays existing water supply system and the development of a bulk water facilities as well as the operation and management of the water supply distribution system of Majayjay, Laguna. It appears from the Water Contract that the PROJECT is an important and priority project of Majayjay but there was no publication and approval of the same as required under Section 4 of the R.A. No. 7718 which mandates that: SEC. 4. Section 4 of the same act is hereby amended to read as follows: Sec. 4. Priority Projects. - All concerned government agencies, including government-owned andcontrolled corporations and local government units, shall include in their development programs those priority projects that may be nanced, constructed, operated and maintained by the private sector under the provisions of this Act. It shall be the duty of all concerned government agencies to give wide publicity to all projects eligible for nancing under this Act, including publication in national and, where applicable, international newspapers of general circulation once every six (6) months and official notication of project proponents registered with them. The list of all such national projects must be part of the development programs of the agencies concerned. The list of projects costing up to Five hundred million

pesos (P500,000,000)4 shall be submitted to ICC of NEDA for its approval and to the NEDA Board for projects costing more than Five hundred million pesos (P500,000,000)5. The list of projects submitted to ICC of the NEDA Board shall be acted upon within thirty (30) working days. The list of local projects to be implemented by the local government units concerned shall be submitted, for conrmation, to the municipal development council for projects costing up to Twenty million pesos; those costing above Twenty up to Fifty million pesos, to the provincial development council; those costing up to Fifty million, to the city development council; above Fifty million up to Two hundred million pesos, to the regional development councils; and those above Two hundred million pesos, to ICC of NEDA. (Emphasis ours) The PROJECT did not undergo the required publication of the project in national newspaper of general circulation once every six (6) months. Neither is there any record showing that the PROJECT was submitted for confirmation to the Municipal Development Council or to the Provincial Development Council or the Regional Development Council, as the case may be, or the project was submitted to NEDA for its approval. In the first place, the PROJECT could not have been submitted for confirmation by Municipal Development Council or the Provincial Development Council or the Regional Development Council or the approval by NEDA because the Water Contract does not state the COST of the PROJECT. There is a complete absence of PROJECT COST in the Water Contract. Thus, it is quite clear that the PROJECT and the Water Contract were made in gross violation of Section 4 of R. A. No. 7718. B. The PROJECT did not comply with the public bidding requirement under Sections 5 and 6 of R.A. No. 7718.

4 5

As amended by ICC-NEDA As amended by ICC-NEDA

The subject contract was executed pursuant to the Unsolicited Proposal of IBDC but R.A. No. 7718 provides certain requirements to be considered as unsolicited proposal. Further, R.A. No. 7718 requires the publication of the PROJECT and public bidding even for unsolicited proposal. SEC. 5. A new section is hereby added after Section 4 of the same Act and numbered as Section 4-A, to read as follows: "SEC. 4-A. Unsolicited Proposals. - Unsolicited proposals for projects may be accepted by any government agency or local government unit on a negotiated basis: Provided, That, all the following conditions are met: (1) such projects involve a new concept or technology and/or are not part of the list of priority projects, (2) no direct government guarantee, subsidy or equity is required, and (3) the government agency or local government unit has invited by publication, for three (3) consecutive weeks, in a newspaper of general circulation, comparative or competitive proposals and no other proposal is received for a period of sixty (60) working days: Provided, further, That in the event another proponent submits a lower price proposal, the original proponent shall have the right to match that price within thirty (30) working days." (Emphasis ours) SEC. 6. Section 5 of the same Act is hereby amended to read as follows: "SEC. 5. Public Bidding of Projects. - Upon approval of the projects mentioned in Section 4 of this Act, the head of the infrastructure agency or local government unit concerned shall forthwith cause to be published, once every week for three (3) consecutive weeks, in at least two (2) newspapers of general circulation and in at least one (1) local newspaper which is circulated in the region, province, city or municipality in which the project is to be constructed, a notice inviting all prospective

infrastructure or development project proponents to participate in a competitive public bidding for the projects so approved. "In the case of a build-operate-and-transfer arrangement, the contract shall be awarded to the bidder who, having satisfied the minimum financial, technical, organizational and legal standards required by this Act, has submitted the lowest bid and most favorable terms for the project, based on the present value of its proposed tolls, fees, rentals and charges over a fixed term for the facility to be constructed, rehabilitated, operated and maintained according to the prescribed minimum design and performance standards, plans and specifications. For this purpose, the winning project proponent shall be automatically granted by the appropriate agency the franchise to operate and maintain the facility, including the collection of tolls, fees, rentals, and charges in accordance with Section 5 hereof. xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx xxx

"The public bidding must be conducted under a two-envelope/two-stage system: the first envelope to contain the technical proposal and the second envelope to contain the financial proposal. The procedures for this system shall be outlined in the implementing rules and regulations of this Act. "A copy of each contract involving a project entered into under this Act shall forthwith be submitted to Congress for its information." (Emphasis ours) It does not appear from the subject contract that the supposed unsolicited proposal of IBDC was published in a newspaper of general circulation for three (3) consecutive weeks in at least two (2) newspapers of general circulation and one (1) local newspaper which is circulated in the regions, province, city or municipality in which the project is to be constructed. As provided in the subject contract, what has been published on June 22, 2011 in Remate is merely

the Invitation to Apply for Eligibility and to Submit Comparative Proposal. This Invitation to Apply for Eligibility and to Submit Comparative Proposal is not the required public bidding of the alleged unsolicited proposal of IBDC. Even then, the said publication in Remate would not constitute as sufficient compliance with Section 5 of R.A. No. 7718 because what is required therein is publication for three (3) consecutive weeks in newspaper of general circulation. Worse, the period of time provided under Section 5 of R.A. 7718 for the submission of the comparative proposal is for a period of sixty (60) working days but even before the expiration of these sixty (60) working days, Majayjay have already executed the Water Contract with IBDC. The invitation to submit comparative proposal was supposedly published on June 22, 2011 in Remate. Counting the said required period of sixty (60) working days from June 22, 2011, the said sixty (60) working days will expire on September 15, 2011 but the Water Contract was executed on August 1, 2011 or twenty eight (28) working days before the expiration of the said 60 days period. On this score alone, the Water Contract has openly and grossly violated the BOT Law. Further, assuming for the sake of argument without in any way conceding that the alleged publication made on June 22, 2011 in Remate is a publication of the questioned unsolicited proposal, still the same would not be a sufficient compliance with the required publication under Section 6 of R.A. No. 7718 because what is required therein is publication of the unsolicited proposal once every week for three (3) consecutive weeks, in at least two (2) newspaper of general circulation and in at least one (1) local newspaper which is circulated in the region, province, city or municipality in which the project is to be constructed. Clearly then, the Water Contract was executed in flagrant violation of the required publication and public bidding as provided under R. A. No. 7718. C. The PROJECT did not comply with the repayment scheme requirement under Sections 8 of R.A. No. 7718.

Moreover, not only did the subject contract violate Sections 5 and 6 of R.A. No. 7718 but the same has likewise violated Section 8 thereof which provides that: SEC. 8. Section 6 of the same Act is hereby amended to read as follows:

"SEC. 6. Repayment Scheme. - For the financing, construction, operation and maintenance of any infrastructure project undertaken through the BuildOperate-and-Transfer arrangement or any of its variations pursuant to the provisions of this Act, the project proponent shall be repaid by authorizing it to charge and collect reasonable tolls, fees, and rentals for the use of the project facility not exceeding those incorporated in the contract and, where applicable, the proponent may likewise be repaid in the form of a share in the revenue of the project or other non-monetary payments, such as, but not limited to, the grant of a portion or percentage of the reclaimed land, subject to the constitutional requirements with respect to the ownership of land: Provided, That for negotiated contracts, and for projects which have been granted a natural monopoly or where the public has no access to alternative facilities, the appropriate government regulatory bodies, shall approve the tolls, fees, rentals, and charges based on a reasonable rate of return: Provided, further, That the imposition and collection of tolls, fees, rentals, and charges shall be for a fixed term as proposed in the bid and incorporated in the contract but in no case shall this term exceed fifty (50) years: Provided, furthermore, That the tolls, fees, rentals, and charges may be subject to adjustment during the life of the contract, based on a predetermined formula using official price indices and included in the instructions to bidders and in the contract: Provided, also, That all tolls, fees, rentals, and charges and adjustments thereof shall take into account the reasonableness of said rates to the end-users of private sector-built infrastructure: Provided, finally, That during the lifetime of the franchise, the project proponent shall undertake the necessary maintenance and repair of the facility in accordance with standards prescribed in the bidding documents and in the contract. In the case of a Build-and-Transfer arrangement, the repayment scheme is to be effected through amortization payments by the government agency or local government unit concerned to the project

proponent according to the scheme proposed in the bid and incorporated in the contract." (Emphasis ours) Section 8 of R.A. No. 7718 clearly provides that the maximum term of a BOT contract shall not exceed fifty (50) years. But the subject contract provides for a mind boggling term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension. Not only that. The subject contract provides for a term of 100 years and the sharing scheme from the revenues to be generated from the PROJECT in the proportion of ninety percent (90%) in favor of IBDC and ten percent (10%) only in favor of Majayjay but the subject contract does not provide and specifically stipulate the COST of PROJECT. The subject contract is completely silent on the PROJECT Cost which is material and essential not only for the approval of the PROJECT as mentioned-above but also to determine repayment scheme provided under Section 8 of R.A. No. 7718. Without the PROJECT COST, the repayment scheme for the PROJECT cannot be determined. Thus, this is another clear violation of the BOT Law. It is quite ridiculous that the subject contract allowed for a term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension, as well as provide for the stipulation on the sharing of the revenues in the proportion of ninety percent (90%) in favor of IBDC and ten percent (10%) only in favor of Majayjay but it does not specifically stipulate for the PROJECT COST which is the sole responsibility and obligation of IBDC. 3. Section 8 of Executive Order No. 423 dated April 30, 2005 is not applicable to the subject contract and that the subject contract is contrary to the Procurement Law. It may be argued that the subject contract is not based upon the BOT Law because the subject contract provides that the formal proposal of IBDC was treated as an unsolicited proposal in accordance with the aforestated GUIDELINES. However, the said GUIDELINES for JV pursuant to Section 8 of E.O. No. 423 dated April 30, 2005 will find no application to the subject contract because Section 4.0 of E.O. No. 423, sub-paragraph 4.1, explicitly provides that Local Government Units (LGUs) are not covered by these Guidelines.

10

Assuming for the sake of argument without in any way conceding that E.O. No. 423 dated April 30, 2005 is applicable to the subject contract, still, the subject contract is null and void for it was executed in violation of Section 12 of E.O. No. 423 dated April 30, 2005 which explicitly provides that Procurement contracts of local government units, regardless of the source of funds, shall be subject to the provisions of Republic Act No. 9184 and its implementing Rules and Regulations. The subject contract is, without a doubt, in violation of Republic Act No. 9184 because the said law requires certain procedures on competitive bidding. Republic Act No. 9184 requires preparation of bidding documents following the standard forms and manuals prescribed by the GPPB,6 preprocurement conference,7 advertising of invitation to bid,8 pre-bid conference,9 eligibility requirements of a prospective bidder shall be made under oath,10 submission of Bids shall have technical and financial components,11 all Bids shall be accompanied by Bid security, 12 opening of all the Bids publicly at a specified date, time and place,13 Bid evaluation,14 post qualification,15 notice of Award,16 and performing security.17 In awarding the subject contract to IBDC, it appears that there is no record of compliance with the foregoing requirements of Republic Act No. 9184. The subject contract is neither a negotiated procurement as it does not fall to any of the thirteen (13) types of a negotiated procurement applicable in specific and distinct situation enumerated under the Revised Implementing Rules and Regulation of Republic Act No. 9184. 4. The subject contract is contrary to morals and public policy.

The subject contract is contrary to morals and public policy because it virtually granted to IBDC the exclusive right/authority and the sole control to

6 7

Section 17, Republic Act No. 9184. Section 20, Republic Act No. 9184. 8 Section 21, Republic Act No. 9184. 9 Section 22, Republic Act No. 9184. 10 Section 23, Republic Act No. 9184. 11 Section 25, Republic Act No. 9184. 12 Section 27, Republic Act No. 9184. 13 Section 28, Republic Act No. 9184. 14 Article IX, Republic Act No. 9184. 15 Article X, Republic Act No. 9184. 16 Section 37, Republic Act No. 9184. 17 Section 39, Republic Act No. 9184.

11

extract, develop and manage all the water resources of Majayjay for the next 100 years or until 2111. In other words, the subject contract practically limited the rights of Majayjay and its residents/inhabitants to exercise and enjoy its water resources. Not only that. The subject contract explicitly provides for a sharing in revenues generated from the PROJECT under the sharing agreement of 90% in favor of IBDC and only 10% in favor of Majayjay . Yet, the subject contract does not provide and stipulate for the COST of the PROJECT which shall be the sole responsibility of IBDC. It has been held by the Supreme Court that the governing principle is that parties may not contract away applicable provisions of law, especially peremptory provisions dealing with matters heavily impressed with public interest.18 Otherwise, the contract is denied legal existence, deemed inexistent and void from the beginning.19 It is a general rule that agreements against public policy are

illegal and void. Under the principles relating to the doctrine of public policy, as applied to the law of contracts, courts of justice will not recognize or uphold any transaction which, in its object operation, or tendency, is calculated to be prejudicial to the public welfare, to sound morality, or to civic honesty. The test is whether the parties have stipulated for something inhibited by the law or inimical to, or inconsistent with, the public welfare. An agreement is against public policy if it is injurious to the interests of the public, contravenes some established interest of society, violates some public statute, is against good morals, ends to interfere with the public welfare or society, or as it is sometimes put, if it is at war with the interests of society and is in conflict with the morals of the time. An agreement either to do anything which, or not to do anything the omission of which, is in any degree clearly injurious to the public and an agreement of such a nature that it cannot be carried into execution without reaching beyond the parties and exercising an injurious influence over the community at large are against public policy. xxx The question whether a contract is against public policy depends upon its purpose and tendency, and not upon the fact that no harm results from it. In other words all agreements the purpose of which is to create a situation which tends to operate to the detriment of the public interest are against public policy and void , whether in the particular case the purpose of the agreement is or is not effectuated. For a particular

18 19

Ibid. Dacasin vs. Dacasin, G.R. No. 168785, February 5, 2010.

12

undertaking to be against public policy actual injury need not be shown; it is enough if the potentialities for harm are present. (12 Am. Jur., pp. 662664).20

As mentioned above, the subject contract grants sole and exclusive authority to IBDC to extract water from Mangulila, Patak-Patak, Sinabak Spring, Gundala Springs and the surface water of Dalitiwan River . On top of it, the subject contract granted IBDC the right to extract water from all water sources of Majayjay under the principle of right of first refusal. In other words, by virtue of the subject contract, IBDC has the sole and absolute control over all water resources of Majayjay, Laguna for the next 100 years or until 2111. Stated differently, on account of the Water Contract, Majayjay and its residents/inhabitants would be deprived of the rights to use and enjoy all water sources of Majayjay for the next 100 years or until 2111 in favor of IBDC without need of public bidding and even if IBDC did not pay a single centavo to Majayjay for the award of such enormous water rights. The payment to Majayjay will not come from the pocket of IBDC but from the ten percent (10%) share of Majayjay from the revenues to be generated from the PROJECT. As the saying goes in the vernacular, ang Majayjay ay iginisa sa sarili nitong mantika. A true public servant with social conscience will not allow such thing to happen to his beloved town. Also, IBDC does not have any authority under its Articles of Incorporation to engage in water business. The primary and secondary purposes of the Articles of Incorporation of IBDC do not show and indicate of any authority for IBDC to engage in waterworks and/or in the operation, management maintenance and rehabilitation of waterworks and water facilities. IBDC is not a water utility company or company engaged in water business but a company engaged in realty business as stated in the primary purpose of its Articles of Incorporation. More so, IBDC does not have the required experience and technical expertise for water extraction and in the construction, rehabilitation, operation and management of water facilities. A copy each of the original and amended Articles of Incorporation of IBDC are hereto attached as Annex D and E, respectively. However, notwithstanding, the absence of authority and power of IBDC to enter into the business of waterworks and/or in the construction, installation, operation and management of water facilities, IBDC entered into and executed the

20

Sy Suan and Price Incorporated vs. Regala, G.R. No. L-9506, June 30, 1956.

13

subject contract, and the previous administration of Majayjay have knowingly and willingly allowed it. This action of IBDC is an ultra vires act. Ultra vires acts

or acts which are clearly beyond the scope of ones authority are null and void and cannot be given any effect.21 An act of the corporation which is either illegal or outside of express, implied or incidental powers as so provided by law or the charter would be void under Article 5 of the Civil Code, and the act is not susceptible to ratification.22

5. The subject contract is greatly disadvantageous against the Municipality of Majayjay.

The subject contract is greatly disadvantageous and prejudicial against Majayjay and its residents/inhabitants for reasons that: a. For the next 100 years or until 2111, IBDC shall have the exclusive right and authority to extract water not only from Mangulila, Patak-

Patak, Sinabak Spring, Gundala Springs and the surface water of Dalitiwan River but from all water sources of Majayjay.

b.

This exclusive right and authority granted to IBDC was made without any appropriate public bidding and/or in violation of BOT Law and the Procurement Law and without payment of even a single centavo to Majayjay. IBDC was granted such exclusive right and sole authority to extract water from all sources in Majayjay without specifically stipulating in clear term the COST of the PROJECT which is the sole obligation and responsibility of IBDC. In other words, IBDC shall and will enjoy such exclusive water rights without corresponding specific obligation on the COST of the PROJECT.

IBDC was granted the lion share from the revenues to be generated from the PROJECT under the sharing agreement of 90% in favor of IBDC and only 10% in favor of Majayjay but the corresponding

c.

d.

21 22

Acebedo Optical Company, Inc. vs. The Honorable Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 100152. March 31, 2000. Rural Bank of Milaor (Camarines Sur) vs. Ocfemia, G.R. No. 137686, February 8, 2000, Separate Concurring Opinion of Justice Vitug.

14

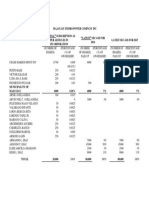

obligation of IBDC for the PROJECT COST is not clearly and specifically stipulated in the Water Contract. e. IBDC was granted the exclusive right to extract water from all water sources of Majayjay beyond its corporate life. A corporation has a corporate life of fifty (50) years only. IBDC was incorporated and registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on May 20, 1993 or its corporate life is only until 2043. So, when it was granted by the Municipality of Majayjay, Laguna of such water rights the remaining corporate life of IBDC was only thirty two (32) years but the term given to IBDC to exercise such right was for 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension, or until 2111. In other words, for the next 100 years or until 2111, or long after the expiration of its corporate life, IBDC shall and will continue to enjoy the exclusive right to extract all water sources of Majayjay. IBDC was granted the exclusive right to extract water from all sources of Majayjay for the period of 100 years and under the sharing agreement of 90% in favor of IBDC and only 10% in favor of the Municipality of Majayjay but it appears from the Financial Statements of IBDC for the years 2010 and 2009 that it does not have the required financial capacity to undertake the PROJECT. As provided in its Balance Sheet (copy of which is enclosed hereto as Annex F) attached to IBDCs Financial Statements for the years 2009 and 2010 submitted to SEC, IBDC has an authorized capitalization of P10,000,000.00 but the Cash on Hand and in Bank of IBDC for 2009 was only P445,567.89, while for 2010 its Cash on Hand and in Bank was only P450,721.35. This clearly shows that, at the time material to the execution of the Water Contract, IBDC does not have the financial capacity to undertake the PROJECT. State differently, IBDC will finance its undertaking under the PROJECT not from its pocket but from the revenues to be generated from the PROJECT. Again, as the saying goes in the vernacular, ang Majayjay ay iginisa sa sarili nitong mantika.

f.

6.

The subject contract is inexistent and void from the beginning.

From the face of the subject contract, it will appear that it has a noble purpose of improving the water distribution facilities of Majayjay at no cost to

15

Majayjay. A closer examination, however, of the subject contract will show that its object or purpose is not noble but devious. It appears that the ultimate and hidden object or purpose of the Water Contract is to enable IBDC to appropriate for itself [and to the great prejudice of Majayjay and its residents/inhabitants] the exclusive water rights and authority to extract all the water resources of Majayjay for the next 100 years or until 2111, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension, without need of public bidding and without paying even a single centavo to Majayjay in consideration for the award of such water rights. This ultimate and hidden object or purpose of the subject contract is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy. This ultimate and hidden objective or purpose of the subject contract is shown from the fact that IBDC filed and submitted to Laguna Lake Development Authority (LLDA) three (3) applications for issuance of water permits to its name in three (3) separate locations in Majayjay, to wit: Brgys. Malinao, Piit and Amonoy, and upon verification from LLDA we have found that you have issued a certification to the effect that you have no objection to said water permit applications of IBDC. A copy each of the said three (3) applications for water permits of IBDC are hereto attached as Annexes G, H and I, respectively. IBDC does not have the authority to apply under its name any water permit from any and all sources of water in Majayjay because the subject contract explicitly provides that such right to apply for water permit exclusively belongs to Majayjay. Under the subject contract, the role of IBDC in the application for water permit is merely to provide assistance in the application of Majayjay. By giving no objection to said three (3) applications of IBDC for water permits, the previous administration of Majayjay have in effect impliedly authorized IBDC to appropriate for itself the water rights over the said three (3) sources of water in Majayjay. Such act is undeniably greatly disadvantageous and prejudicial to Majayjay and its residents/inhabitants. It is a plain and simple betrayal of public trust. On account of which, the inhabitants and residents of Majayjay were put under the whimps and caprices of a private corporation which does not have any authority, experience, technical expertise and financial capacity to operate a water system or water facility. The subject contract is absolutely simulated and fictitious because, as repeatedly mentioned above, it does not specifically stipulate the COST of the PROJECT. The subject contract is also completely silent on the consideration to be paid by IBDC for the award to it of the questioned exclusive water rights over all water resources of Majayjay. What is clear from the subject contract is that

16

payment to Majayjay will not come from the pocket of IBDC but from the ten percent (10%) share of Majayjay from the revenues to be generated from the PROJECT. Thus, the subject contract is absolutely simulated and fictitious as it does not have stipulation on the specific consideration to be paid by IBDC to Majayjay for the award to it of such water rights for a term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension. Moreover, the object or purpose of Water Contract, among other things, is to grant the award of water rights to IBDC over all water resources of Majayjay for the next 100 years inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension. It bears to remind that water rights belong to the State and not to Majayjay. Thus, water right is outside the commerce of men. Only the State can grant and award water rights. In short, water rights are outside the commerce of men. In plain words, the object of subject contract -water rights is beyond the commerce of men, thus, the Water Contract is inexistent and void from the beginning. Article 1409 of the Civil Code mandates that: Art. 1409. The following contracts inexistent and void from the beginning: are

1. Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy; 2. Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious; xxx xxx xxx 4. Those whose object is outside the commerce of men. xxx xxx xxx These contracts cannot be ratified. Neither can the right to set up the defense of illegality be waived. Conclusion: In view of the foregoing discussion, we opine that the subject contract is void and inexistent from the beginning. The subject contract is not an ordinary contract. It is a government contract. Unlike regular contracts and agreements, government contracts should comply with all the requisites provided by laws. Government contract are governed and regulated by special laws, failure to

17

comply with which renders them void.23 The Supreme Court held in COMELEC vs. Quijano-Padilla24 that the contract, as expressly declared by law, is inexistent and void ab initio. This is to say that the proposed contract is without force and effect from the very beginning or from its incipiency , as if it had never been entered into, and hence, cannot be validated either by lapse of time or ratification. The Supreme Court also declared in Tatad vs. Garcia, Jr.25 that any government contract entered into without the required public bidding is null and void and cannot adversely affect the rights of third parties. The Supreme Court has time and again ruled that (a) void or inexistent contract is one which has no force and effect from the very beginningit is as if it has never been entered into and cannot be validated either by the passage of time or ratification.26 It is worth stressing that (a) contract that violates the Constitution and the law is null and void ab initio and vests no rights and creates no obligation.27 Recommendation: Accordingly, we respectfully submit and recommend that the subject water contract can be unilaterally cancelled by the local government of Majayjay as the same is void and inexistent from the beginning. The Sangguniang Bayan of Majayjay may pass a Resolution cancelling and setting aside the subject contract. No judicial action is necessary to set aside a void contract. Such action would be merely declaratory.28 Thus, the Supreme Court declared in E. Razon, Inc. vs. Philippine Ports Authority29 that the Philippine Ports Authority could unilaterally cancel a void management contract. In the same vein, the Municipality of Majayjay can unilaterally cancel the subject contract as the case of E. Razon squarely applies in this case. In both cases, the contract is a government contract which is contrary to law and thus in itself null and void. As the Supreme Court declared in E. Razon case, it was well within the rights of the Philippine Ports Authority to unilaterally cancel and treat as avoided the Management Contract and no arbitrariness may be attached to its exercise of this right.

23 24

Department of Health vs. C.V. Conchela & Associates Architects, 475 SCRA 218 [2005]. 438 Phil. 72 [2002]. 25 243 SCRA 436. 26 Yun Kwan Byung vs. Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation, 608 SCRA 107 [2009]. 27 Chavez vs. Presidential Commission on Good Government, 307 SCRA 394. 28 Aquino, Ramon C., The Civil Code of the Philippines, vol. 2, 1990 ed., p. 492. 29 151 SCRA 233 [1987].

18

Most importantly, we strongly recommend that the Municipality of Majayjay should stop the implementation of the subject water contract. In other words, the Municipality of Majayjay cannot and should not enforce or implement the subject water contract for it will be a blatant violation of the well-established jurisprudence that a void contract cannot be enforced. Thus, the Municipality of Majayjay cannot and should not make any payment to IBDC; otherwise, such payment will most likely be disallowed by the Commission On Audit (COA) and for which the responsible public officers shall be liable to make corresponding reimbursement for whatever payment received by IBDC. The Supreme Court had ruled in numerous occasions that a void contract cannot be enforced. In Dacasin vs. Dacasin,30 the Supreme Court held that the trial court cannot enforce the Agreement which is contrary to law. In Ty vs. Banco Filipino and Savings Bank,31 the Supreme Court declared that a void trust agreement cannot be enforced. In Flores vs. Bagaoisan,32 the Supreme Court declared that the conveyance of a homestead before the expiration of the five-year prohibitory period following the issuance of the homestead patent is null and void and cannot be enforced, for it is not within the competence of any citizen to barter away what public policy by law seeks to preserve. There is, therefore, no doubt that the Deed of Confirmation and Quitclaim, which was executed three years after the homestead patent was issued, is void and cannot be enforced. Finally, once the contract is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order, or public policy, such contract is denied legal existence and it shall be deemed inexistent and void from the beginning and hence cannot be enforced. A void contract is equivalent to nothing and is absolutely wanting in civil effects. It cannot be validated either by ratification or prescription.33 The rationale behind this is that a void contract vests no rights and creates no obligation. If the contract does not create any right and obligation, there is therefore nothing to enforce. Please be guided accordingly.

30 31

G.R. No. 168785, February 5, 2010. G.R. No. 188302, June 27, 2012. 32 G.R. No. 173365, April 15, 2010. 33 Fuentes vs. Roca, G.R. No. 178902, April 21, 2010.

19

Very truly yours,

PATERNO L. ESMAQUEL

MEILINE C. MEDALLA-MAQUILING Cc: Hon. Victorino Z. Rodillas Municipal Mayor Majayjay, Laguna The Sangguniang Bayan of Majayjay, Laguna c/o Hon. Lauro C. Mentilla Vice Mayor Majayjay, Laguna

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- RisingDokument12 SeitenRisingJecky Delos ReyesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comelec vs. Quijano - Shorter VersionDokument2 SeitenComelec vs. Quijano - Shorter VersionMatet VenturaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOJ OPINION 72 s.2003Dokument10 SeitenDOJ OPINION 72 s.2003Katleya Kate BelderolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decree No. 153-2007-ND-CP of October 15 - 2007Dokument11 SeitenDecree No. 153-2007-ND-CP of October 15 - 2007Anonymous 7uoreiQKONoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Bank vs. AtlantaDokument3 SeitenLand Bank vs. AtlantaPrecious AnneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 25.1. Solis v. BarrosoDokument18 Seiten25.1. Solis v. BarrosoJeffrey DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position Paper On Administrative Case Involving The Iloilo City Supplementary Contract Award Before The Ombudsman PDFDokument8 SeitenPosition Paper On Administrative Case Involving The Iloilo City Supplementary Contract Award Before The Ombudsman PDFJacob BlackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obli Digests 3rd ExamDokument21 SeitenObli Digests 3rd ExamelizbalderasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decree 63 2018 ND CPDokument59 SeitenDecree 63 2018 ND CPAnonymous AGI56jqm2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Position Paper On Administrative Case Involving The Iloilo City Supplementary Contract Award Before The OmbudsmanDokument8 SeitenPosition Paper On Administrative Case Involving The Iloilo City Supplementary Contract Award Before The OmbudsmanManuel Mejorada100% (14)

- PNCC V CA, GR 116896, May 5, 1997Dokument3 SeitenPNCC V CA, GR 116896, May 5, 1997Marcial Gerald Suarez III100% (1)

- Abaya vs. Ebdane-CasDokument3 SeitenAbaya vs. Ebdane-CasJose Emmanuel Carodan100% (2)

- 5013 2021 14 1502 31099 Judgement 11-Nov-2021Dokument93 Seiten5013 2021 14 1502 31099 Judgement 11-Nov-2021Kamal AshokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cancellation of Letter of IntentDokument10 SeitenCancellation of Letter of IntentmasoodbhattiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dynamic BuildersDokument2 SeitenDynamic BuildersElaizza ConcepcionNoch keine Bewertungen

- JV Agreement for LGU-Private Reclamation ProjectDokument6 SeitenJV Agreement for LGU-Private Reclamation ProjectBikoy EstoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Basis of Condominiums and Condominium PlanDokument5 SeitenLegal Basis of Condominiums and Condominium PlanELIXABETH LEENoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax 3Dokument12 SeitenTax 3Dennis Aran Tupaz AbrilNoch keine Bewertungen

- (New) 2018-02-26 - PPP Decree 15 Draft - English TranslationDokument41 Seiten(New) 2018-02-26 - PPP Decree 15 Draft - English TranslationV HNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPP - Swiss ChallengeDokument5 SeitenPPP - Swiss ChallengeApple Ke-eNoch keine Bewertungen

- MacMac S NotesDokument92 SeitenMacMac S Notesjetzon2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leandro Verceles V COA - Case DigestDokument7 SeitenLeandro Verceles V COA - Case DigestAnonymous lokXJkc7l7Noch keine Bewertungen

- GenSan PPP-Code-2015Dokument38 SeitenGenSan PPP-Code-2015chelzedecko2146Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pradeep Singh Pahal and Kavita Ahuja Case SummaryDokument3 SeitenPradeep Singh Pahal and Kavita Ahuja Case Summarydk0895Noch keine Bewertungen

- CMS PDFDokument4 SeitenCMS PDFRecordTrac - City of OaklandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaint Affidavit Graft Case Vs Senate President Drilon Et Al Over Anomalous Esplanade II Project in Iloilo City.Dokument7 SeitenComplaint Affidavit Graft Case Vs Senate President Drilon Et Al Over Anomalous Esplanade II Project in Iloilo City.Manuel MejoradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salient Points EO 74 (Reclamation)Dokument12 SeitenSalient Points EO 74 (Reclamation)Marx Earvin TorinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd BatchDokument4 Seiten2nd BatchElmer BarnabusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alternative Dispute Resolution CasesDokument25 SeitenAlternative Dispute Resolution CasesDon So Hiong100% (1)

- Republic Act No. 10884Dokument3 SeitenRepublic Act No. 10884ecbt.subscriptionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Architecture Firm in Payment DisputeDokument483 SeitenSupreme Court Rules in Favor of Architecture Firm in Payment DisputeJustin CebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akash Chakole ZindabadDokument4 SeitenAkash Chakole Zindabadaakash chakoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation Zone Bill Draft - Update.1.31.2021Dokument18 SeitenInnovation Zone Bill Draft - Update.1.31.2021Colton Lochhead100% (4)

- An overview of Real Estate Law in BangladeshDokument6 SeitenAn overview of Real Estate Law in BangladeshSk. Mannaf ShawonNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPP Decree EnglishDokument39 SeitenPPP Decree EnglishV HNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2.phil Export Vs EusebioDokument3 Seiten2.phil Export Vs Eusebiomaria lourdes lopenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rehabilitation of Bridge Barangay DangdanglaDokument32 SeitenRehabilitation of Bridge Barangay DangdanglaJohn Rheynor MayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bid DocsDokument37 SeitenBid DocsAndrew BenitezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Build Lease and Transfer AgreementDokument8 SeitenBuild Lease and Transfer AgreementMunicipal Planning and Development Officer Office0% (1)

- Phil RealtyDokument27 SeitenPhil RealtyKj SantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CASE DIGEST - COMELEC vs. Padilla (G.R. No. 151992 September 18, 2002)Dokument1 SeiteCASE DIGEST - COMELEC vs. Padilla (G.R. No. 151992 September 18, 2002)Aphr100% (1)

- Villanueva Vs Mayor Felix VDokument7 SeitenVillanueva Vs Mayor Felix Vm_ramas2001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Consultancy Sir JakeDokument5 SeitenConsultancy Sir Jakemelchor latinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manish Kumar Vs Union of India UOI and Ors 1901202SC20212001211057171COM112670Dokument169 SeitenManish Kumar Vs Union of India UOI and Ors 1901202SC20212001211057171COM112670xoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC rules Loan Agreement between Japan and PH as executive agreementDokument6 SeitenSC rules Loan Agreement between Japan and PH as executive agreementSharon BakerNoch keine Bewertungen

- EPG Construction Vs VigilarDokument10 SeitenEPG Construction Vs VigilarRelmie TaasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Order 1035 Streamlines Gov't Land AcquisitionDokument5 SeitenExecutive Order 1035 Streamlines Gov't Land Acquisitionahsiri22Noch keine Bewertungen

- RA 7160 Ammendment RA 8150Dokument4 SeitenRA 7160 Ammendment RA 8150gbenjielizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- MC-13-03guidelines For Section 4.2Dokument11 SeitenMC-13-03guidelines For Section 4.2roy rubaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Housing and Land Use Regulatory BoardDokument7 SeitenHousing and Land Use Regulatory Boardroy rubaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resettlement and Compensation for Hydropower ProjectDokument13 SeitenResettlement and Compensation for Hydropower ProjectAbhilekh PaudelNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission Case Against Rohtas Project LtdDokument17 SeitenNational Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission Case Against Rohtas Project LtdTusar KoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Export V EusebioDokument3 SeitenPhilippine Export V EusebiowesleybooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIR Ruling No 455-07Dokument7 SeitenBIR Ruling No 455-07Peggy SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- YU TEK and CO vs. BASILIO GONZALES, G.R. No. L-9935, February 1, 1915 FactsDokument4 SeitenYU TEK and CO vs. BASILIO GONZALES, G.R. No. L-9935, February 1, 1915 FactsStar Salimbo-GandamraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument7 SeitenCase DigestSittie Hayah A. AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act on Contracts to Which a Local Government Is a PartyVon EverandAct on Contracts to Which a Local Government Is a PartyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsVon EverandIntroduction to Negotiable Instruments: As per Indian LawsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- 2017 Davis-Stirling Common Interest DevelopmentVon Everand2017 Davis-Stirling Common Interest DevelopmentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Payments For CompensationDokument1 SeiteSummary of Payments For CompensationRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- COA - 98-002 - Prohibition Against Employment by Local Government Units of Private Lawyers ToDokument3 SeitenCOA - 98-002 - Prohibition Against Employment by Local Government Units of Private Lawyers ToYan Rodriguez DasalNoch keine Bewertungen

- LETTER Dated April 6, 2021Dokument8 SeitenLETTER Dated April 6, 2021Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Opinion No. 04 Series 2014 (Provincial Atty. of Laguna)Dokument4 SeitenLegal Opinion No. 04 Series 2014 (Provincial Atty. of Laguna)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 4 December 2020Dokument2 SeitenLetter Dated 4 December 2020Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 18 December 2020Dokument2 SeitenLetter Dated 18 December 2020Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated August 3, 2020 From COADokument1 SeiteLetter Dated August 3, 2020 From COARomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Dated March 19, 2021 (MCTC Magdalena)Dokument11 SeitenDecision Dated March 19, 2021 (MCTC Magdalena)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position Paper (MHCI-Amando Diaz)Dokument14 SeitenPosition Paper (MHCI-Amando Diaz)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Counter Affidavit of RespondentsDokument32 SeitenCounter Affidavit of RespondentsRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Dated June 17, 2016 (Mentilla Vs OMB, PPP)Dokument13 SeitenDecision Dated June 17, 2016 (Mentilla Vs OMB, PPP)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service of Order And-Or Sobpoena OrderDokument5 SeitenService of Order And-Or Sobpoena OrderRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Dated Feb. 21, 2013 (OMB Administrative Case)Dokument21 SeitenDecision Dated Feb. 21, 2013 (OMB Administrative Case)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated March 19, 2014 (Mayor Rodillas To Atty. Pat)Dokument1 SeiteLetter Dated March 19, 2014 (Mayor Rodillas To Atty. Pat)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position Paper (Mary Rose Almarinez)Dokument30 SeitenPosition Paper (Mary Rose Almarinez)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Dated 17 June 2016 (Majayjay)Dokument13 SeitenDecision Dated 17 June 2016 (Majayjay)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 30 March 2016 From Office of The OmbudsmanDokument1 SeiteLetter Dated 30 March 2016 From Office of The OmbudsmanRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 01 March 2016Dokument11 SeitenLetter Dated 01 March 2016Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Articles of Incorporation (MHCI)Dokument8 SeitenArticles of Incorporation (MHCI)Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 29 April 2016Dokument15 SeitenLetter Dated 29 April 2016Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated March 25, 2013Dokument2 SeitenLetter Dated March 25, 2013Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 27 April 2016 To Brgy. Chairman Darius VitasaDokument2 SeitenLetter Dated 27 April 2016 To Brgy. Chairman Darius VitasaRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 27 April 2016 To The Office of The Municipal MayorDokument3 SeitenLetter Dated 27 April 2016 To The Office of The Municipal MayorRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resolution No. 116 S. 2006 With MOADokument11 SeitenResolution No. 116 S. 2006 With MOARomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name of ProjectDokument1 SeiteName of ProjectRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 31 March 2016 From Atty. GlenDokument2 SeitenLetter Dated 31 March 2016 From Atty. GlenRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter To The Office of The Governor Dated Nov. 11, 2015Dokument7 SeitenLetter To The Office of The Governor Dated Nov. 11, 2015Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breaking News Dated August 26, 2015Dokument4 SeitenBreaking News Dated August 26, 2015Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letter Dated 27 April 2016 To Brgy. Chairman Condrado BrosasDokument2 SeitenLetter Dated 27 April 2016 To Brgy. Chairman Condrado BrosasRomulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Majayjay Hydro Power Comp., Inc.Dokument1 SeiteMajayjay Hydro Power Comp., Inc.Romulo UrciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Survey QuestionnaireDokument5 SeitenSurvey QuestionnaireYour PlaylistNoch keine Bewertungen

- Renew Notary Commission CebuDokument13 SeitenRenew Notary Commission CebuEdsoul Melecio Estorba100% (1)

- Revised Rules On Summary ProcedureDokument9 SeitenRevised Rules On Summary ProcedurerockradarNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDokument25 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- PERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS UNDER PHILIPPINE LAWDokument4 SeitenPERSONS AND FAMILY RELATIONS UNDER PHILIPPINE LAWCathyrine JabagatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The LLP ActDokument13 SeitenThe LLP ActshanumanuranuNoch keine Bewertungen

- in Re - Petition of Al Argosino To Take The Lawyers Oath (1997)Dokument3 Seitenin Re - Petition of Al Argosino To Take The Lawyers Oath (1997)Franch GalanzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Private CaveatDokument1 SeitePrivate CaveatIZZAH ZAHIN100% (2)

- CASE DIGESTS ON ADMINISTRATIVE LAWDokument21 SeitenCASE DIGESTS ON ADMINISTRATIVE LAWSittie Jean M. CanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. Anthony Braithwaite, 4th Cir. (2012)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Anthony Braithwaite, 4th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Rules On Summary Procedure and Judicial Affidavit RuleDokument12 SeitenRevised Rules On Summary Procedure and Judicial Affidavit RuleDis Cat100% (1)

- Corporation Law Case Digest 20 Cases For MergeDokument40 SeitenCorporation Law Case Digest 20 Cases For MergeMa Gabriellen Quijada-Tabuñag100% (1)

- DepEd Central Office RolesDokument20 SeitenDepEd Central Office RolesMae T OlivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cancio Jr. v. IsipDokument1 SeiteCancio Jr. v. IsipRywNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filinvest Land, Inc Vs CADokument2 SeitenFilinvest Land, Inc Vs CAis_still_artNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daan v. Sandiganbayan, GR Nos. 163972-77, March 28, 2008Dokument1 SeiteDaan v. Sandiganbayan, GR Nos. 163972-77, March 28, 2008Jemson Ivan WalcienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copyright Case DoctrinesDokument5 SeitenCopyright Case DoctrinesKarl CabarlesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nuisance DigestDokument21 SeitenNuisance DigestAshAngeLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statutes and Its PartsDokument24 SeitenStatutes and Its PartsShahriar ShaonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kirinyaga County Public Service Board - Vacancies-21st Feb 2015Dokument8 SeitenKirinyaga County Public Service Board - Vacancies-21st Feb 2015Governor Joseph NdathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resolution Trust Corporation, As Receiver For Sioux Valley Savings and Loan Association v. Robert J. Krogh, 982 F.2d 529, 10th Cir. (1992)Dokument2 SeitenResolution Trust Corporation, As Receiver For Sioux Valley Savings and Loan Association v. Robert J. Krogh, 982 F.2d 529, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Access To Buildings For People With DisabilitiesDokument4 SeitenAccess To Buildings For People With DisabilitiesJNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill of Rights 1689Dokument1 SeiteBill of Rights 1689yojustpassingbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Non-Probate Assets ChartDokument1 SeiteNon-Probate Assets ChartseabreezeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 - The Iloilo Ice and Cold Storage Company V, Publc Utility Board G.R. No. L-19857 (March 2, 1923)Dokument13 Seiten4 - The Iloilo Ice and Cold Storage Company V, Publc Utility Board G.R. No. L-19857 (March 2, 1923)Lemuel Montes Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. ChavesDokument2 SeitenPeople vs. ChavesAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0Noch keine Bewertungen

- Agreement Between Author and Publisher MJSDokument4 SeitenAgreement Between Author and Publisher MJSmadhuchikkakall7113Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Truth Commission Case DigestDokument7 SeitenPhilippines Truth Commission Case DigestJf LarongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rodriguez Vs RavilanDokument3 SeitenRodriguez Vs RavilanElerlenne LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fabricator Phil v. EstolasDokument5 SeitenFabricator Phil v. EstolasGilbertNoch keine Bewertungen