Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rule 61 Support Pendente Lite

Hochgeladen von

quericzOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rule 61 Support Pendente Lite

Hochgeladen von

quericzCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

RULE 61

Support Pendente Lite

1) G.R. Nos. 175279-80 June 5, 2013 SUSAN LIM-LUA, vs.DANILO Y. LUA, Respondent. Petitioner,

Respondent filed a motion for reconsideration,7 asserting that petitioner is not entitled to spousal support considering that she does not maintain for herself a separate dwelling from their children and respondent has continued to support the family for their sustenance and well-being in accordance with familys social and financial standing. As to the P250,000.00 granted by the trial court as monthly support pendente lite, as well as the P1,750,000.00 retroactive support, respondent found it unconscionable and beyond the intendment of the law for not having considered the needs of the respondent. In its May 13, 2004 Order, the trial court stated that the March 31, 2004 Order had become final and executory since respondents motion for reconsideration is treated as a mere scrap of paper for violation of the threeday notice period under Section 4, Rule 15 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, as amended, and therefore did not interrupt the running of the period to appeal. Respondent was given ten (10) days to show cause why he should not be held in contempt of the court for disregarding the March 31, 2004 order granting support pendente lite.8 His second motion for reconsideration having been denied, respondent filed a petition for certiorari in the CA. On April 12, 2005, the CA rendered its Decision,9 finding merit in respondents contention that the trial court gravely abused its discretion in granting P250,000.00 monthly support to petitioner without evidence to prove his actual income. The said court thus decreed: WHEREFORE, foregoing premises considered, this petition is given due course. The assailed Orders dated March 31, 2004, May 13, 2004, June 4, 2004 and June 18, 2004 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 14, Cebu City issued in Civil Case No. CEB No. 29346 entitled "Susan Lim Lua versus Danilo Y. Lua" are hereby nullified and set aside and instead a new one is entered ordering herein petitioner: a) to pay private respondent a monthly support pendente lite of P115,000.00 beginning the month of April 2005 and every month thereafter within the first five (5) days thereof; b) to pay the private respondent the amount of P115,000.00 a month multiplied by the number of months starting from September 2003 until March 2005 less than the amount supposedly given by petitioner to the private respondent as her and their two (2) children monthly support; and c) to pay the costs. SO ORDERED.10 Neither of the parties appealed this decision of the CA. In a Compliance11 dated June 28, 2005, respondent attached a copy of a check he issued in the amount of P162,651.90 payable to petitioner. Respondent explained that, as decreed in the CA decision, he deducted from the amount of support in arrears (September 3, 2003 to March 2005) ordered by the CA -- P2,185,000.00 -- plus P460,000.00 (April, May, June and July 2005), totaling P2,645,000.00, the advances given by him to his children and petitioner in the sum of P2,482,348.16 (with attached photocopies of receipts/billings).

In this petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45, petitioner seeks to set aside the Decision1 dated April 20, 2006 and Resolution2 dated October 26, 2006 of the Court of Appeals (CA) dismissing her petition for contempt (CA-G.R. SP No. 01154) and granting respondent's petition for certiorari (CA-G.R. SP No. 01315). The factual background is as follows: On September 3, 2003,3 petitioner Susan Lim-Lua filed an action for the declaration of nullity of her marriage with respondent Danilo Y. Lua, docketed as Civil Case No. CEB-29346 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Cebu City, Branch 14. In her prayer for support pendente lite for herself and her two children, petitioner sought the amount of P500,000.00 as monthly support, citing respondents huge earnings from salaries and dividends in several companies and businesses here and abroad.4 After due hearing, Judge Raphael B. Yrastorza, Sr. issued an Order 5 dated March 31, 2004 granting support pendente lite, as follows: From the evidence already adduced by the parties, the amount of Two Hundred Fifty (P250,000.00) Thousand Pesos would be sufficient to take care of the needs of the plaintiff. This amount excludes the One hundred thirty-five (P135,000.00) Thousand Pesos for medical attendance expenses needed by plaintiff for the operation of both her eyes which is demandable upon the conduct of such operation. The amounts already extended to the two (2) children, being a commendable act of defendant, should be continued by him considering the vast financial resources at his disposal. According to Art. 203 of the Family Code, support is demandable from the time plaintiff needed the said support but is payable only from the date of judicial demand. Since the instant complaint was filed on 03 September 2003, the amount of Two Hundred Fifty (P250,000.00) Thousand should be paid by defendant to plaintiff retroactively to such date until the hearing of the support pendente lite. P250,000.00 x 7 corresponding to the seven (7) months that lapsed from September, 2003 to March 2004 would tantamount to a total of One Million Seven Hundred Fifty (P1,750,000.00) Thousand Pesos. Thereafter, starting the month of April 2004, until otherwise ordered by this Court, defendant is ordered to pay a monthly support of Two Hundred Fifty Thousand (P250,000.00) Pesos payable within the first five (5) days of each corresponding month pursuant to the third paragraph of Art. 203 of the Family Code of the Philippines. The monthly support of P250,000.00 is without prejudice to any increase or decrease thereof that this Court may grant plaintiff as the circumstances may warrant i.e. depending on the proof submitted by the parties during the proceedings for the main action for support. 6

Page 1 of 14

In her Comment to Compliance with Motion for Issuance of a Writ of Execution,12 petitioner asserted that none of the expenses deducted by respondent may be chargeable as part of the monthly support contemplated by the CA in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740. On September 27, 2005, the trial court issued an Order13 granting petitioners motion for issuance of a writ of execution as it rejected respondents interpretation of the CA decision. Respondent filed a motion for reconsideration and subsequently also filed a motion for inhibition of Judge Raphael B. Yrastorza, Sr. On November 25, 2005, Judge Yrastorza, Sr. issued an Order14 denying both motions. WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing premises, both motions are DENIED. Since a second motion for reconsideration is prohibited under the Rules, this denial has attained finality; let, therefore, a writ of execution be issued in favor of plaintiff as against defendant for the accumulated support in arrears pendente lite. Notify both parties of this Order. SO ORDERED.15 Since respondent still failed and refused to pay the support in arrears pendente lite, petitioner filed in the CA a Petition for Contempt of Court with Damages, docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 01154 ("Susan Lim Lua versus Danilo Y. Lua"). Respondent, on the other hand, filed CA-G.R. SP No. 01315, a Petition for Certiorari under Rule 65 of the Rules of Court ("Danilo Y. Lua versus Hon. Raphael B. Yrastorza, Sr., in his capacity as Presiding Judge of Regional Trial Court of Cebu, Branch 14, and Susan Lim Lua"). The two cases were consolidated. By Decision dated April 20, 2006, the CA set aside the assailed orders of the trial court, as follows: WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered: a) DISMISSING, for lack of merit, the case of Petition for Contempt of Court with Damages filed by Susan Lim Lua against Danilo Y. Lua with docket no. SP. CA-GR No. 01154; b) GRANTING Danilo Y. Luas Petition for Certiorari docketed as SP. CA-GR No. 01315. Consequently, the assailed Orders dated 27 September 2005 and 25 November 2005 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 14, Cebu City issued in Civil Case No. CEB-29346 entitled "Susan Lim Lua versus Danilo Y. Lua, are hereby NULLIFIED and SET ASIDE, and instead a new one is entered: i. ORDERING the deduction of the amount of PhP2,482,348.16 plus 946,465.64, or a total of PhP3,428,813.80 from the current total support in arrears of Danilo Y. Lua to his wife, Susan Lim Lua and their two (2) children; ii. ORDERING Danilo Y. Lua to resume payment of his monthly support of PhP115,000.00 pesos starting from the time payment of this amount was deferred by him subject to the deductions aforementioned.

iii. DIRECTING the issuance of a permanent writ of preliminary injunction. SO ORDERED.16 The appellate court said that the trial court should not have completely disregarded the expenses incurred by respondent consisting of the purchase and maintenance of the two cars, payment of tuition fees, travel expenses, and the credit card purchases involving groceries, dry goods and books, which certainly inured to the benefit not only of the two children, but their mother (petitioner) as well. It held that respondents act of deferring the monthly support adjudged in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740 was not contumacious as it was anchored on valid and justifiable reasons. Respondent said he just wanted the issue of whether to deduct his advances be settled first in view of the different interpretation by the trial court of the appellate courts decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740. It also noted the lack of contribution from the petitioner in the joint obligation of spouses to support their children. Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration but it was denied by the CA. Hence, this petition raising the following errors allegedly committed by the CA: I. THE HONORABLE COURT ERRED IN NOT FINDING RESPONDENT GUILTY OF INDIRECT CONTEMPT. II. THE HONORABLE COURT ERRED IN ORDERING THE DEDUCTION OF THE AMOUNT OF PHP2,482,348.16 PLUS 946,465.64, OR A TOTAL OF PHP3,428,813.80 FROM THE CURRENT TOTAL SUPPORT IN ARREARS OF THE RESPONDENT TO THE PETITIONER AND THEIR CHILDREN.17 The main issue is whether certain expenses already incurred by the respondent may be deducted from the total support in arrears owing to petitioner and her children pursuant to the Decision dated April 12, 2005 in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740. The pertinent provision of the Family Code of the Philippines provides: Article 194. Support comprises everything indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. The education of the person entitled to be supported referred to in the preceding paragraph shall include his schooling or training for some profession, trade or vocation, even beyond the age of majority. Transportation shall include expenses in going to and from school, or to and from place of work. (Emphasis supplied.) Petitioner argues that it was patently erroneous for the CA to have allowed the deduction of the value of the two cars and their maintenance costs from the support in arrears, as these items are not indispensable to the sustenance of the family or in keeping them

Page 2 of 14

alive. She points out that in the Decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740, the CA already considered the said items which it deemed chargeable to respondent, while the monthly support pendente lite (P115,000.00) was fixed on the basis of the documentary evidence of respondents alleged income from various businesses and petitioners testimony that she needed P113,000.00 for the maintenance of the household and other miscellaneous expenses excluding the P135,000.00 medical attendance expenses of petitioner. Respondent, on the other hand, contends that disallowing the subject deductions would result in unjust enrichment, thus making him pay for the same obligation twice. Since petitioner and the children resided in one residence, the groceries and dry goods purchased by the children using respondents credit card, totallingP594,151.58 for the period September 2003 to June 2005 were not consumed by the children alone but shared with their mother. As to the Volkswagen Beetle and BMW 316i respondent bought for his daughter Angelli Suzanne Lua and Daniel Ryan Lua, respectively, these, too, are to be considered advances for support, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. Respondent stressed that being children of parents belonging to the upper-class society, Angelli and Daniel Ryan had never in their entire life commuted from one place to another, nor do they eat their meals at "carinderias". Hence, the cars and their maintenance are indispensable to the childrens day-to-day living, the value of which were properly deducted from the arrearages in support pendente lite ordered by the trial and appellate courts. As a matter of law, the amount of support which those related by marriage and family relationship is generally obliged to give each other shall be in proportion to the resources or means of the giver and to the needs of the recipient.18 Such support comprises everything indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. Upon receipt of a verified petition for declaration of absolute nullity of void marriage or for annulment of voidable marriage, or for legal separation, and at any time during the proceeding, the court, motuproprio or upon verified application of any of the parties, guardian or designated custodian, may temporarily grant support pendente lite prior to the rendition of judgment or final order. 19 Because of its provisional nature, a court does not need to delve fully into the merits of the case before it can settle an application for this relief. All that a court is tasked to do is determine the kind and amount of evidence which may suffice to enable it to justly resolve the application. It is enough that the facts be established by affidavits or other documentary evidence appearing in the record.20 In this case, the amount of monthly support pendente lite for petitioner and her two children was determined after due hearing and submission of documentary evidence by the parties. Although the amount fixed by the trial court was reduced on appeal, it is clear that the monthly support pendente lite of P115,000.00 ordered by the CA was intended primarily for the sustenance of petitioner and her children, e.g., food, clothing, salaries of drivers and house helpers, and other household expenses. Petitioners testimony also mentioned the cost of regular therapy for her scoliosis and vitamins/medicines. ATTY. ZOSA: x xxx Q How much do you spend for your food and your two (2) children every month?

A Presently, Sir? ATTY. ZOSA: Yes. A For the food alone, I spend not over P40,000.00 to P50,000.00 a month for the food alone. x xxx ATTY. ZOSA: Q What other expenses do you incur in living in that place? A The normal household and the normal expenses for a family to have a decent living, Sir. Q How much other expenses do you incur? WITNESS: A For other expenses, is around over a P100,000.00, Sir. Q Why do you incur that much amount? A For the clothing for the three (3) of us, for the vitamins and medicines. And also I am having a special therapy to straighten my back because I am scoliotic. I am advised by the Doctor to hire a driver, but I cannot still afford it now. Because my eyesight is not reliable for driving. And I still need another househelp to accompany me whenever I go marketing because for my age, I cannot carry anymore heavy loads. x xxx ATTY. FLORES: x xxx Q On the issue of the food for you and the two (2) children, you mentioned P40,000.00 to P50,000.00? A Yes, for the food alone. Q Okay, what other possible expenses that you would like to include in those two (2) items? You mentioned of a driver, am I correct? A Yes, I might need two (2) drivers, Sir for me and my children. Q Okay. How much would you like possibly to pay for those two (2) drivers? A I think P10,000.00 a month for one (1) driver. So I need two (2) drivers. And I need another househelp. Q You need another househelp. The househelp nowadays would charge you something between P3,000.00 to P4,000.00. Thats quite

Page 3 of 14

A Right now, my househelp is receiving P8,000.00. I need another which I will give a compensation of P5,000.00. Q Other than that, do you still have other expenses? A My clothing. COURT: How about the schooling for your children? WITNESS: A The schooling is shouldered by my husband, Your Honor. COURT: Everything? A Yes, Your Honor. x xxx ATTY. FLORES: Q Madam witness, let us talk of the present needs. x xx. What else, what specific need that you would like to add so I can tell my client, the defendant. WITNESS: A I need to have an operation both of my eyes. I also need a special therapy for my back because I am scoliotic, three (3) times a week. Q That is very reasonable. [W]ould you care to please repeat that? A Therapy for my scoliotic back and then also for the operation both of my eyes. And I am also taking some vitamins from excel that will cost P20,000.00 a month. Q Okay. Lets have piece by piece. Have you asked the Doctor how much would it cost you for the operation of that scoliotic? A Yes before because I was already due last year. Before, this eye will cost P60,000.00 and the other eyes P75,000.00. Q So for both eyes, you are talking of P60,000.00 plus P75,000.00 is P135,000.00? A Yes. x xxx Q You talk of therapy? A Yes. Q So how much is that?

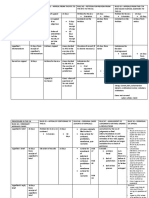

A Around P5,000.00 a week.21 As to the financial capacity of the respondent, it is beyond doubt that he can solely provide for the subsistence, education, transportation, health/medical needs and recreational activities of his children, as well as those of petitioner who was then unemployed and a full-time housewife. Despite this, respondents counsel manifested during the same hearing that respondent was willing to grant the amount of only P75,000.00 as monthly support pendente lite both for the children and petitioner as spousal support. Though the receipts of expenses submitted in court unmistakably show how much respondent lavished on his children, it appears that the matter of spousal support was a different matter altogether. Rejecting petitioners prayer for P500,000.00 monthly support and finding the P75,000.00 monthly support offered by respondent as insufficient, the trial court fixed the monthly support pendente lite at P250,000.00. However, since the supposed income in millions of respondent was based merely on the allegations of petitioner in her complaint and registration documents of various corporations which respondent insisted are owned not by him but his parents and siblings, the CA reduced the amount of support pendente lite to P115,000.00, which ruling was no longer questioned by both parties. Controversy between the parties resurfaced when respondents compliance with the final CA decision indicated that he deducted from the total amount in arrears (P2,645,000.00) the sum of P2,482,348.16, representing the value of the two cars for the children, their cost of maintenance and advances given to petitioner and his children. Respondent explained that the deductions were made consistent with the fallo of the CA Decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740 ordering him to pay support pendente lite in arrears less the amount supposedly given by him to petitioner as her and their two childrens monthly support. The following is a summary of the subject deductions under Compliance dated June 28, 2005, duly supported by receipts22: Car purchases Suzanne and Daniel Ryan for Angelli Php1,350,000.00 613,472.86

Car Maintenance fees of Angelli - 51,232.50 Suzanne Credit card statements of Daniel 348,682.28 Ryan Car Maintenance fees of Daniel 118,960.52 Ryan Php2,482,348.16 After the trial court disallowed the foregoing deductions, respondent filed a motion for reconsideration further asserting that the following amounts, likewise with supporting receipts, be considered as additional advances given to petitioner and the children23: Medical expenses of Susan Lim- Php 42,450.71 Lua Dental Expenses of Daniel Ryan Travel expenses of Susan Lim-Lua 11,500.00 14,611.15

Credit card purchases of Angelli 408,891.08 Suzanne

Page 4 of 14

Salon and travel expenses of 87,112.70 Angelli Suzanne School expenses of Daniel Ryan 260,900.00 Lua Cash given to Daniel and Angelli TOTAL GRAND TOTAL 121,000.00 Php 946,465.64 Php 3,428,813.80

Sec. 3. Child Support.The common children of the spouses shall be supported from the properties of the absolute community or the conjugal partnership. Subject to the sound discretion of the court, either parent or both may be ordered to give an amount necessary for the support, maintenance, and education of the child. It shall be in proportion to the resources or means of the giver and to the necessities of the recipient. In determining the amount of provisional support, the court may likewise consider the following factors: (1) the financial resources of the custodial and non-custodial parent and those of the child; (2) the physical and emotional health of the child and his or her special needs and aptitudes; (3) the standard of living the child has been accustomed to; (4) the non-monetary contributions that the parents will make toward the care and well-being of the child. The Family Court may direct the deduction of the provisional support from the salary of the parent. Since the amount of monthly support pendente lite as fixed by the CA was not appealed by either party, there is no controversy as to its sufficiency and reasonableness. The dispute concerns the deductions made by respondent in settling the support in arrears. On the issue of crediting of money payments or expenses against accrued support, we find as relevant the following rulings by US courts. In Bradford v. Futrell,25 appellant sought review of the decision of the Circuit Court which found him in arrears with his child support payments and entered a decree in favor of appellee wife. He complained that in determining the arrearage figure, he should have been allowed full credit for all money and items of personal property given by him to the children themselves, even though he referred to them as gifts. The Court of Appeals of Maryland ruled that in the suit to determine amount of arrears due the divorced wife under decree for support of minor children, the husband (appellant) was not entitled to credit for checks which he had clearly designated as gifts, nor was he entitled to credit for an automobile given to the oldest son or a television set given to the children. Thus, if the children remain in the custody of the mother, the father is not entitled to credit for money paid directly to the children if such was paid without any relation to the decree. In the absence of some finding of consent by the mother, most courts refuse to allow a husband to dictate how he will meet the requirements for support payments when the mode of payment is fixed by a decree of court. Thus he will not be credited for payments made when he unnecessarily interposed himself as a volunteer and made payments direct to the children of his own accord. Wills v. Baker, 214 S. W. 2d 748 (Mo. 1948); Openshaw v. Openshaw, 42 P. 2d 191 (Utah 1935). In the latter case the court said in part: "The payments to the children themselves do not appear to have been made as payments upon alimony, but were rather the result of his fatherly interest in the welfare of those children. We do not believe he should be permitted to charge them to plaintiff. By so doing he would be determining for Mrs. Openshaw the manner in which she should expend her allowances. It is a very easy thing for children to say their mother will not give them money, especially as they may realize that such a plea is effective in attaining their ends. If she is not treating them right the courts are open to the father for redress."26

The CA, in ruling for the respondent said that all the foregoing expenses already incurred by the respondent should, in equity, be considered advances which may be properly deducted from the support in arrears due to the petitioner and the two children. Said court also noted the absence of petitioners contribution to the joint obligation of support for their children. We reverse in part the decision of the CA. Judicial determination of support pendente lite in cases of legal separation and petitions for declaration of nullity or annulment of marriage are guided by the following provisions of the Rule on Provisional Orders24 Sec. 2. Spousal Support.In determining support for the spouses, the court may be guided by the following rules: (a) In the absence of adequate provisions in a written agreement between the spouses, the spouses may be supported from the properties of the absolute community or the conjugal partnership. (b) The court may award support to either spouse in such amount and for such period of time as the court may deem just and reasonable based on their standard of living during the marriage. (c) The court may likewise consider the following factors: (1) whether the spouse seeking support is the custodian of a child whose circumstances make it appropriate for that spouse not to seek outside employment; (2) the time necessary to acquire sufficient education and training to enable the spouse seeking support to find appropriate employment, and that spouses future earning capacity; (3) the duration of the marriage; (4) the comparative financial resources of the spouses, including their comparative earning abilities in the labor market; (5) the needs and obligations of each spouse; (6) the contribution of each spouse to the marriage, including services rendered in home-making, child care, education, and career building of the other spouse; (7) the age and health of the spouses; (8) the physical and emotional conditions of the spouses; (9) the ability of the supporting spouse to give support, taking into account that spouses earning capacity, earned and unearned income, assets, and standard of living; and (10) any other factor the court may deem just and equitable. (d) The Family Court may direct the deduction of the provisional support from the salary of the spouse.

Page 5 of 14

In Martin, Jr. v. Martin,27 the Supreme Court of Washington held that a father, who is required by a divorce decree to make child support payments directly to the mother, cannot claim credit for payments voluntarily made directly to the children. However, special considerations of an equitable nature may justify a court in crediting such payments on his indebtedness to the mother, when such can be done without injustice to her. The general rule is to the effect that when a father is required by a divorce decree to pay to the mother money for the support of their dependent children and the unpaid and accrued installments become judgments in her favor, he cannot, as a matter of law, claim credit on account of payments voluntarily made directly to the children. Koon v. Koon, supra; Briggs v. Briggs, supra. However, special considerations of an equitable nature may justify a court in crediting such payments on his indebtedness to the mother, when that can be done without injustice to her. Briggs v. Briggs, supra. The courts are justifiably reluctant to lay down any general rules as to when such credits may be allowed.28 (Emphasis supplied.) Here, the CA should not have allowed all the expenses incurred by respondent to be credited against the accrued support pendente lite. As earlier mentioned, the monthly support pendente lite granted by the trial court was intended primarily for food, household expenses such as salaries of drivers and house helpers, and also petitioners scoliosis therapy sessions. Hence, the value of two expensive cars bought by respondent for his children plus their maintenance cost, travel expenses of petitioner and Angelli, purchases through credit card of items other than groceries and dry goods (clothing) should have been disallowed, as these bear no relation to the judgment awarding support pendente lite. While it is true that the dispositive portion of the executory decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740 ordered herein respondent to pay the support in arrears "less than the amount supposedly given by petitioner to the private respondent as her and their two (2) children monthly support," the deductions should be limited to those basic needs and expenses considered by the trial and appellate courts. The assailed ruling of the CA allowing huge deductions from the accrued monthly support of petitioner and her children, while correct insofar as it commends the generosity of the respondent to his children, is clearly inconsistent with the executory decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740. More important, it completely ignores the unfair consequences to petitioner whose sustenance and well-being, was given due regard by the trial and appellate courts. This is evident from the March 31, 2004 Order granting support pendente lite to petitioner and her children, when the trial court observed: While there is evidence to the effect that defendant is giving some forms of financial assistance to his two (2) children via their credit cards and paying for their school expenses, the same is, however, devoid of any form of spousal support to the plaintiff, for, at this point in time, while the action for nullity of marriage is still to be heard, it is incumbent upon the defendant, considering the physical and financial condition of the plaintiff and the overwhelming capacity of defendant, to extend support unto the latter. x x x29 On appeal, while the Decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 84740 reduced the amount of monthly support fixed by the trial court, it nevertheless held that considering respondents financial resources, it is but fair and just that he give a monthly support for the sustenance and basic necessities of petitioner and his children. This would imply that any amount respondent seeks to be credited as monthly support should only cover those incurred for sustenance and household expenses.1avvphi1

In the case at bar, records clearly show and in fact has been admitted by petitioner that aside from paying the expenses of their two (2) childrens schooling, he gave his two (2) children two (2) cars and credit cards of which the expenses for various items namely: clothes, grocery items and repairs of their cars were chargeable to him which totaled an amount of more than One Hundred Thousand (P100,000.00) for each of them and considering that as testified by the private respondent that she needs the total amount of P113,000.00 for the maintenance of the household and other miscellaneous expenses and considering further that petitioner can afford to buy cars for his two (2) children, and to pay the expenses incurred by them which are chargeable to him through the credit cards he provided them in the amount of P100,000.00 each, it is but fair and just that the monthly support pendente lite for his wife, herein private respondent, be fixed as of the present in the amount of P115,000.00 which would be sufficient enough to take care of the household and other needs. This monthly support pendente lite to private respondent in the amount of P115,000.00 excludes the amount of One Hundred ThirtyFive (P135,000.00) Thousand Pesos for medical attendance expenses needed by private respondent for the operation of both her eyes which is demandable upon the conduct of such operation. Likewise, this monthly support of P115,000.00 is without prejudice to any increase or decrease thereof that the trial court may grant private respondent as the circumstances may warrant i.e. depending on the proof submitted by the parties during the proceedings for the main action for support. The amounts already extended to the two (2) children, being a commendable act of petitioner, should be continued by him considering the vast financial resources at his disposal.30 (Emphasis supplied.) Accordingly, only the following expenses of respondent may be allowed as deductions from the accrued support pendente lite for petitioner and her children: 1wphi1 Medical expenses of Susan Lim-Lua Dental Expenses of Daniel Ryan Credit card purchases of Angelli Php 42,450.71 11,500.00 365,282.20

(Groceries and Dry Goods) 228,869.38 Credit Card purchases of Daniel Ryan TOTAL Php 648,102.29

As to the contempt charge, we sustain the CA in holding that respondent is not guilty of indirect contempt. Contempt of court is defined as a disobedience to the court by acting in opposition to its authority, justice, and dignity. It signifies not only a willful disregard or disobedience of the courts order, but such conduct which tends to bring the authority of the court and the administration of law into disrepute or, in some manner, to impede the due administration of justice.31 To constitute contempt, the act must be done willfully and for an illegitimate or improper purpose. 32 The good faith, or lack of it, of the alleged contemnor should be considered.33 Respondent admittedly ceased or suspended the giving of monthly support pendente lite granted by the trial court, which is immediately executory. However, we agree with the CA that respondents act was

Page 6 of 14

not contumacious considering that he had not been remiss in actually providing for the needs of his children. It is a matter of record that respondent continued shouldering the full cost of their education and even beyond their basic necessities in keeping with the familys social status. Moreover, respondent believed in good faith that the trial and appellate courts, upon equitable grounds, would allow him to offset the substantial amounts he had spent or paid directly to his children. Respondent complains that petitioner is very much capacitated to generate income on her own because she presently maintains a boutique at the Ayala Center Mall in Cebu City and at the same time engages in the business of lending money. He also claims that the two children have finished their education and are now employed in the family business earning their own salaries. Suffice it to state that the matter of increase or reduction of support should be submitted to the trial court in which the action for declaration for nullity of marriage was filed, as this Court is not a trier of facts. The amount of support may be reduced or increased proportionately according to the reduction or increase of the necessities of the recipient and the resources or means of the person obliged to support.34 As we held in Advincula v. Advincula35 Judgment for support does not become final. The right to support is of such nature that its allowance is essentially provisional; for during the entire period that a needy party is entitled to support, his or her alimony may be modified or altered, in accordance with his increased or decreased needs, and with the means of the giver. It cannot be regarded as subject to final determination.36 WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTLY GRANTED. The Decision dated April 20, 2006 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP Nos. 01154 and 01315 is hereby MODIFIED to read as follows: "WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered: a) DISMISSING, for lack of merit, the case of Petition for Contempt of Court with Damages filed by Susan Lim Lua against Danilo Y. Lua with docket no. SP. CA-G.R. No. 01154; b) GRANTING IN PART Danilo Y. Lua's Petition for Certiorari docketed as SP. CA-G.R. No. 01315. Consequently, the assailed Orders dated 27 September 2005 and 25 November 2005 of the Regional Trial Court, Branch 14, Cebu City issued in Civil Case No. CEB-29346 entitled "Susan Lim Lua versus Danilo Y. Lua, are hereby NULLIFIED and SET ASIDE, and instead a new one is entered: i. ORDERING the deduction of the amount of Php 648,102.29 from the support pendente lite in arrears of Danilo Y. Lua to his wife, Susan Lim Lua and their two (2) children; ii. ORDERING Danilo Y. Lua to resume payment of his monthly support of PhP115,000.00 pesos starting from the time payment of this amount was deferred by him subject to the deduction aforementioned.

iii. DIRECTING the immediate execution of this judgment. SO ORDERED."

2) G.R. NO. 165166 - August 15, 2012] CHARLES GOTARDO,Petitioner, v.DIVINA BULING,Respondent. We resolve the Petition for Review on certiorari, 1 filed by petitioner Charles Gotardo, to challenge the March 5, 2004 decision 2 and the July 27, 2004 resolution3 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA GR CV No. 76326. The CA decision ordered the petitioner to recognize and provide legal support to his minor son, Gliffze 0. Buling. The CA resolution denied the petitioner's subsequent motion for reconsideration. FACTUAL BACKGROUND On September 6, 1995, respondent DivinaBuling filed a complaint with the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Maasin, Southern Leyte, Branch 25, for compulsory recognition and support pendente lite, claiming that the petitioner is the father of her child Gliffze.4rll In his answer, the petitioner denied the imputed paternity of Gliffze. 5 For the parties failure to amicably settle the dispute, the RTC terminated the pre-trial proceedings.6 Trial on the merits ensued. The respondent testified for herself and presented Rodulfo Lopez as witness. Evidence for the respondent showed that she met the petitioner on December 1, 1992 at the Philippine Commercial and Industrial Bank, Maasin, Southern Leyte branch where she had been hired as a casual employee, while the petitioner worked as accounting supervisor.7 The petitioner started courting the respondent in the third week of December 1992 and they became sweethearts in the last week of January 1993.8 The petitioner gave the respondent greeting cards on special occasions, such as on Valentine s Day and her birthday; she reciprocated his love and took care of him when he was ill.9rll Sometime in September 1993, the petitioner started intimate sexual relations with the respondent in the former s rented room in the boarding house managed by Rodulfo, the respondent s uncle, on Tomas Oppus St., Agbao, Maasin, Southern Leyte. 10 The petitioner rented the room from March 1, 1993 to August 30, 1994. 11 The sexual encounters occurred twice a month and became more frequent in June 1994; eventually, on August 8, 1994, the respondent found out that she was pregnant.12 When told of the pregnancy, the petitioner was happy and made plans to marry the respondent. 13 They in fact applied for a marriage license.14 The petitioner even inquired about the costs of a wedding reception and the bridal gown. 15 Subsequently, however, the petitioner backed out of the wedding plans.16rll The respondent responded by filing a complaint with the Municipal Trial Court of Maasin, Southern Leyte for damages against the petitioner for breach of promise to marry.17 Later, however, the petitioner and the respondent amicably settled the case.18rll The respondent gave birth to their son Gliffze on March 9, 1995. 19 When the petitioner did not show up and failed to provide support to Gliffze, the respondent sent him a letter on July 24, 1995 demanding recognition of and support for their child.20 When the petitioner did not answer the demand, the respondent filed her complaint for compulsory recognition and support pendente lite.21rll The petitioner took the witness stand and testified for himself. He denied the imputed paternity,22 claiming that he first had sexual contact with the respondent in the first week of August 1994 and she could not have been pregnant for twelve (12) weeks (or three (3)

Page 7 of 14

months) when he was informed of the pregnancy on September 15, 1994.23rll During the pendency of the case, the RTC, on the respondent s motion,24 granted a P2,000.00 monthly child support, retroactive from March 1995.25rll THE RTC RULING In its June 25, 2002 decision, the RTC dismissed the complaint for insufficiency of evidence proving Gliffze s filiation. It found the respondent s testimony inconsistent on the question of when she had her first sexual contact with the petitioner, i.e., "September 1993" in her direct testimony while "last week of January 1993" during her cross-testimony, and her reason for engaging in sexual contact even after she had refused the petitioner s initial marriage proposal. It ordered the respondent to return the amount of support pendente lite erroneously awarded, and to pay P10,000.00 as attorney s fees.26rbl r l l lbrr The respondent appealed the RTC ruling to the CA.27rll chanrobles virtual law library THE CA RULING In its March 5, 2004 decision, the CA departed from the RTC's appreciation of the respondent s testimony, concluding that the latter merely made an honest mistake in her understanding of the questions of the petitioner s counsel. It noted that the petitioner and the respondent had sexual relationship even before August 1994; that the respondent had only one boyfriend, the petitioner, from January 1993 to August 1994; and that the petitioner s allegation that the respondent had previous relationships with other men remained unsubstantiated. The CA consequently set aside the RTC decision and ordered the petitioner to recognize his minor son Gliffze. It also reinstated the RTC order granting a P2,000.00 monthly child support.28rll When the CA denied29 the petitioner s motion for reconsideration,30 the petitioner filed the present Petition for Review on Certiorari . THE PETITION The petitioner argues that the CA committed a reversible error in rejecting the RTC s appreciation of the respondent s testimony, and that the evidence on record is insufficient to prove paternity. THE CASE FOR THE RESPONDENT The respondent submits that the CA correctly explained that the inconsistency in the respondent s testimony was due to an incorrect appreciation of the questions asked, and that the record is replete with evidence proving that the petitioner was her lover and that they had several intimate sexual encounters during their relationship, resulting in her pregnancy and Gliffze s birth on March 9, 1995. THE ISSUE The sole issue before us is whether the CA committed a reversible error when it set aside the RTC s findings and ordered the petitioner to recognize and provide legal support to his minor son Gliffze. OUR RULINGrbl r l l lbrr We do not find any reversible error in the CA s ruling. chanrobles virtual law library We have recognized that "[f]iliation proceedings are usually filed not just to adjudicate paternity but also to secure a legal right associated with paternity, such as citizenship, support (as in this case) or inheritance. [In paternity cases, the burden of proof] is on the person who alleges that the putative father is the biological father of the child."31rll One can prove filiation, either legitimate or illegitimate, through the record of birth appearing in the civil register or a final judgment, an admission of filiation in a public document or a private handwritten

instrument and signed by the parent concerned, or the open and continuous possession of the status of a legitimate or illegitimate child, or any other means allowed by the Rules of Court and special laws.32 We have held that such other proof of one's filiation may be a "baptismal certificate, a judicial admission, a family bible in which [his] name has been entered, common reputation respecting [his] pedigree, admission by silence, the [testimonies] of witnesses, and other kinds of proof [admissible] under Rule 130 of the Rules of Court."33rll In Herrera v. Alba,34 we stressed that there are four significant procedural aspects of a traditional paternity action that parties have to face: a prima faciecase, affirmative defenses, presumption of legitimacy, and physical resemblance between the putative father and the child.35 We explained that a prima faciecase exists if a woman declares supported by corroborative proof that she had sexual relations with the putative father; at this point, the burden of evidence shifts to the putative father.36 We explained further that the two affirmative defenses available to the putative father are: (1) incapability of sexual relations with the mother due to either physical absence or impotency, or (2) that the mother had sexual relations with other men at the time of conception.37rll In this case, the respondent established a prima faciecase that the petitioner is the putative father of Gliffze through testimony that she had been sexually involved only with one man, the petitioner, at the time of her conception.38Rodulfo corroborated her testimony that the petitioner and the respondent had intimate relationship.39rll On the other hand, the petitioner did not deny that he had sexual encounters with the respondent, only that it occurred on a much later date than the respondent asserted, such that it was physically impossible for the respondent to have been three (3) months pregnant already in September 1994 when he was informed of the pregnancy. 40 However, the petitioner failed to substantiate his allegations of infidelity and insinuations of promiscuity. His allegations, therefore, cannot be given credence for lack of evidentiary support. The petitioner s denial cannot overcome the respondent s clear and categorical assertions. The petitioner, as the RTC did, made much of the variance between the respondent s direct testimony regarding their first sexual contact as "sometime in September 1993" and her cross-testimony when she stated that their first sexual contact was "last week of January 1993," as follows:rbl r l l lbrr ATTY. GO CINCO:rl When did the defendant, according to you, start courting you?chanroblesvirtualawlibrary A Third week of December 1992. Q And you accepted him?chanroblesvirtualawlibrary A Last week of January 1993. Q And by October you already had your sexual intercourse?chanroblesvirtualawlibrary A Last week of January 1993. COURT: What do you mean by accepting?chanroblesvirtualawlibrary A I accepted his offer of love.41rll chanrobles virtual law library We find that the contradictions are for the most part more apparent than real, having resulted from the failure of the respondent to comprehend the question posed, but this misunderstanding was later corrected and satisfactorily explained. Indeed, when confronted for her contradictory statements, the respondent explained that that portion of the transcript of stenographic notes was incorrect and she had brought it to the attention of Atty. Josefino Go Cinco (her former counsel) but the latter took no action on the matter.42rll

Page 8 of 14

Jurisprudence teaches that in assessing the credibility of a witness, his testimony must be considered in its entirety instead of in truncated parts. The technique in deciphering a testimony is not to consider only its isolated parts and to anchor a conclusion based on these parts. "In ascertaining the facts established by a witness, everything stated by him on direct, cross and redirect examinations must be calibrated and considered."43 Evidently, the totality of the respondent's testimony positively and convincingly shows that no real inconsistency exists. The respondent has consistently asserted that she started intimate sexual relations with the petitioner sometime in September 1993.44rll Since filiation is beyond question, support follows as a matter of obligation; a parent is obliged to support his child, whether legitimate or illegitimate.45 Support consists of everything indispensable for sustenance, dwelling, clothing, medical attendance, education and transportation, in keeping with the financial capacity of the family. 46 Thus, the amount of support is variable and, for this reason, no final judgment on the amount of support is made as the amount shall be in proportion to the resources or means of the giver and the necessities of the recipient.47 It may be reduced or increased proportionately according to the reduction or increase of the necessities of the recipient and the resources or means of the person obliged to support.48rll In this case, we sustain the award of P2,000.00 monthly child support, without prejudice to the filing of the proper motion in the RTC for the determination of any support in arrears, considering the needs of the child, Gliffze, during the pendency of this case. WHEREFORE, we hereby DENY the petition for lack of merit. The March 5, 2004 decision and the July 27, 2004 resolution of the Court of Appeals in CA GR CV No. 76326 are hereby AFFIRMED. Costs against the petitioner. SO ORDERED.

tuition fees which the defendant has agreed to defray, plus expenses for books and other school supplies), the sum of P42,292.50 per month, effective May 1, 1998, as his share in the monthly support of the children, until further orders from this Court. The first monthly contribution, i.e., for the month of May 1998, shall be given by the defendant to the plaintiff within five (5) days from receipt of a copy of this Order. The succeeding monthly contributions of P42,292.50 shall be directly given by the defendant to the plaintiff without need of any demand, within the first five (5) days of each month beginning June 1998. All expenses for books and other school supplies shall be shouldered by the plaintiff and the defendant, share and share alike. Finally, it is understood that any claim for support-in-arrears prior to May 1, 1998, may be taken up later in the course of the proceedings proper. x xx SO ORDERED.5rl1 The aforesaid order and subsequent orders for support pendente lite were the subject of G.R. No. 139337 entitled "Ma. Carminia C. Roxas v. Court of Appeals and Jose Antonio F. Roxas" decided by this Court on August 15, 2001.6 The Decision in said case declared that "the proceedings and orders issued by the trial court in the application for support pendente lite (and the main complaint for annulment of marriage) in the re-filed case, that is, in Civil Case No. 97-0608 were not rendered null and void by the omission of a statement in the certificate of non-forum shopping regarding the prior filing and dismissal without prejudice of Civil Case No. 97-0523 which involves the same parties." The assailed orders for support pendente lite were thus reinstated and the trial court resumed hearing the main case. On motion of petitioners counsel, the trial court issued an Order dated October 11, 2002 directing private respondent to give support in the amount of P42,292.50 per month starting April 1, 1999 pursuant to the May 19, 1998 Order.7rl1 On February 11, 2003, private respondent filed a Motion to Reduce Support citing, among other grounds, that the P42,292.50 monthly support for the children as fixed by the court was even higher than his then P20,800.00 monthly salary as city councilor.8rl1 After hearing, the trial court issued an Order9 dated March 7, 2005 granting the motion to reduce support and denying petitioners motion for spousal support, increase of the childrens monthly support pendente lite and support-in-arrears. The trial court considered the following circumstances well-supported by documentary and testimonial evidence: (1) the spouses eldest child, Jose Antonio, Jr. is a SangguniangKabataan Chairman and is already earning a monthly salary; (2) all the children stay with private respondent on weekends in their house in Pasay City; (3) private respondent has no source of income except his salary and benefits as City Councilor; (4) the voluminous documents consisting of official receipts in payment of various billings including school tuition fees, private tutorials and purchases of childrens school supplies, personal checks issued by private respondent, as well as his own testimony in court, all of which substantiated his claim that he is fulfilling his obligation of supporting his minor children during the pendency of the action; (5) there is no proof presented by petitioner that she is not gainfully employed, the spouses being both medical doctors; (6) the unrebutted allegation of private respondent that petitioner is already in the United States; and (7) the alleged arrearages of private respondent was not substantiated by petitioner with any evidence while private

3) G.R. No. 185595 : January 9, 2013 MA. CARMINIA C. CALDERON represented by her AttorneyIn-Fact, Marycris V. Baldevia, Petitioner, v.JOSE ANTONIO F. ROXAS and COURT OF APPEALS, Respondent. Before us is a petition for review on certiorari under Rule 45 assailing the Decision1 dated September 9, 2008 and Resolution2 dated December 15, 2008 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CV No. 85384. The CA affirmed the Orders dated March 7, 2005 and May 4, 2005 of the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Paraaque City, Branch 260 in Civil Case No. 97-0608. Petitioner Ma.Carminia C. Calderon and private respondent Jose Antonio F. Roxas, were married on December 4, 1985 and their union produced four children. On January 16, 1998, petitioner filed an Amended Complaint3 for the declaration of nullity of their marriage on the ground of psychological incapacity under Art. 36 of the Family Code of the Philippines. On May 19, 1998, the trial court issued an Order4 granting petitioners application for support pendente lite. Said order states in part:cralawlibrary Accordingly, the defendant is hereby ordered to contribute to the support of the above-named minors, (aside from 50% of their school

Page 9 of 14

respondent had duly complied with his obligation as ordered by the court through his overpayments in other aspects such as the childrens school tuition fees, real estate taxes and other necessities. Petitioners motion for partial reconsideration of the March 7, 2005 Order was denied on May 4, 2005.10rl1 On May 16, 2005, the trial court rendered its Decision 11 in Civil Case No. 97-0608 decreeing thus:cralawlibrary WHEREFORE, judgment (sic):cralawlibrary is hereby rendered declaring

executory. The CA further noted that petitioner failed to avail of the proper remedy to question an interlocutory order. Petitioners motion for reconsideration was likewise denied by the CA. Hence, this petition raising the following issues:cralawlibrary A. DID THE CA COMMIT A GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION and/or REVERSIBLE ERROR WHEN IT RULED THAT THE RTC ORDERS DATED MARCH 7, 2005 AND MAY 4, 2005 ARE MERELY INTERLOCUTORY? B. DID THE CA COMMIT A GRAVE ABUSE OF DISCRETION and/or REVERSIBLE ERROR WHEN IT DISMISSED OUTRIGHT THE APPEAL FROM SAID RTC ORDERS, WHEN IT SHOULD HAVE DECIDED THE APPEAL ON THE MERITS?14rl1rbl rl l lbrr The core issue presented is whether the March 7, 2005 and May 4, 2005 Orders on the matter of support pendente lite are interlocutory or final. This Court has laid down the distinction between interlocutory and final orders, as follows:cralawlibrary x xx A "final" judgment or order is one that finally disposes of a case, leaving nothing more to be done by the Court in respect thereto, e.g., an adjudication on the merits which, on the basis of the evidence presented at the trial, declares categorically what the rights and obligations of the parties are and which party is in the right; or a judgment or order that dismisses an action on the ground, for instance, of res judicata or prescription. Once rendered, the task of the Court is ended, as far as deciding the controversy or determining the rights and liabilities of the litigants is concerned. Nothing more remains to be done by the Court except to await the parties next move (which among others, may consist of the filing of a motion for new trial or reconsideration, or the taking of an appeal) and ultimately, of course, to cause the execution of the judgment once it becomes "final" or, to use the established and more distinctive term, "final and executory." x xx Conversely, an order that does not finally dispose of the case, and does not end the Courts task of adjudicating the parties contentions and determining their rights and liabilities as regards each other, but obviously indicates that other things remain to be done by the Court, is "interlocutory" e.g., an order denying a motion to dismiss under Rule 16 of the Rules, or granting a motion for extension of time to file a pleading, or authorizing amendment thereof, or granting or denying applications for postponement, or production or inspection of documents or things, etc. Unlike a "final" judgment or order, which is appealable, as above pointed out, an "interlocutory" order may not be questioned on appeal except only as part of an appeal that may eventually be taken from the final judgment rendered in the case.15 [Emphasis supplied] The assailed orders relative to the incident of support pendente lite and support in arrears, as the term suggests, were issued pending the rendition of the decision on the main action for declaration of nullity of marriage, and are therefore interlocutory. They did not finally dispose of the case nor did they consist of a final adjudication of the

1. Declaring null and void the marriage between plaintiff Ma.Carmina C. Roxas and defendant Jose Antonio Roxas solemnized on December 4, 1985 at San Agustin Convent, in Manila. The Local Civil Registrar of Manila is hereby ordered to cancel the marriage contract of the parties as appearing in the Registry of Marriage as the same is void; 2. Awarding the custody of the parties minor children Maria Antoinette Roxas, Julian Roxas and Richard Roxas to their mother herein petitioner, with the respondent hereby given his visitorial and or custodial rights at [sic] the express conformity of petitioner. 3. Ordering the respondent Jose Antonio Roxas to provide support to the children in the amount of P30,000.00 a month, which support shall be given directly to petitioner whenever the children are in her custody, otherwise, if the children are in the provisional custody of respondent, said amount of support shall be recorded properly as the amounts are being spent. For that purpose the respondent shall then render a periodic report to petitioner and to the Court to show compliance and for monitoring. In addition, the respondent is ordered to support the proper schooling of the children providing for the payment of the tuition fees and other school fees and charges including transportation expenses and allowances needed by the children for their studies. 4. Dissolving the community property or conjugal partnership property of the parties as the case may be, in accordance with law. Let copies of this decision be furnished the Office of the Solicitor General, the Office of the City Prosecutor, Paranaque City, and the City Civil Registrar of Paranaque City and Manila. SO ORDERED.12rl1 On June 14, 2005, petitioner through counsel filed a Notice of Appeal from the Orders dated March 7, 2005 and May 4, 2005. In her appeal brief, petitioner emphasized that she is not appealing the Decision dated May 16, 2005 which had become final as no appeal therefrom had been brought by the parties or the City Prosecutor or the Solicitor General. Petitioner pointed out that her appeal is "from the RTC Order dated March 7, 2005, issued prior to the rendition of the decision in the main case", as well as the May 4, 2005 Order denying her motion for partial reconsideration. 13rl1 By Decision dated September 9, 2008, the CA dismissed the appeal on the ground that granting the appeal would disturb the RTC Decision of May 16, 2005 which had long become final and

Page 10 of 14

merits of petitioners claims as to the ground of psychological incapacity and other incidents as child custody, support and conjugal assets. The Rules of Court provide for the provisional remedy of support pendente lite which may be availed of at the commencement of the proper action or proceeding, or at any time prior to the judgment or final order.16 On March 4, 2003, this Court promulgated the Rule on Provisional Orders17 which shall govern the issuance of provisional orders during the pendency of cases for the declaration of nullity of marriage, annulment of voidable marriage and legal separation. These include orders for spousal support, child support, child custody, visitation rights, hold departure, protection and administration of common property. Petitioner contends that the CA failed to recognize that the interlocutory aspect of the assailed orders pertains only to private respondents motion to reduce support which was granted, and to her own motion to increase support, which was denied. Petitioner points out that the ruling on support in arrears which have remained unpaid, as well as her prayer for reimbursement/payment under the May 19, 1998 Order and related orders were in the nature of final orders assailable by ordinary appeal considering that the orders referred to under Sections 1 and 4 of Rule 61 of the Rules of Court can apply only prospectively. Thus, from the moment the accrued amounts became due and demandable, the orders under which the amounts were made payable by private respondent have ceased to be provisional and have become final. We disagree. The word interlocutory refers to something intervening between the commencement and the end of the suit which decides some point or matter but is not a final decision of the whole controversy. 18 An interlocutory order merely resolves incidental matters and leaves something more to be done to resolve the merits of the case. In contrast, a judgment or order is considered final if the order disposes of the action or proceeding completely, or terminates a particular stage of the same action.19 Clearly, whether an order or resolution is final or interlocutory is not dependent on compliance or noncompliance by a party to its directive, as what petitioner suggests. It is also important to emphasize the temporary or provisional nature of the assailed orders. Provisional remedies are writs and processes available during the pendency of the action which may be resorted to by a litigant to preserve and protect certain rights and interests therein pending rendition, and for purposes of the ultimate effects, of a final judgment in the case. They are provisional because they constitute temporary measures availed of during the pendency of the action, and they are ancillary because they are mere incidents in and are dependent upon the result of the main action.20 The subject orders on the matter of support pendente lite are but an incident to the main action for declaration of nullity of marriage. Moreover, private respondents obligation to give monthly support in the amount fixed by the RTC in the assailed orders may be enforced by the court itself, as what transpired in the early stage of the proceedings when the court cited the private respondent in contempt of court and ordered him arrested for his refusal/failure to comply with the order granting support pendente lite.21 A few years later, private respondent filed a motion to reduce support while petitioner filed her own motion to increase the same, and in addition sought spousal support and support in arrears. This fact underscores the

provisional character of the order granting support pendente lite. Petitioners theory that the assailed orders have ceased to be provisional due to the arrearages incurred by private respondent is therefore untenable. Under Section 1, Rule 41 of the 1997 Revised Rules of Civil Procedure, as amended, appeal from interlocutory orders is not allowed. Said provision reads:cralawlibrary SECTION 1.Subject of appeal. - An appeal may be taken from a judgment or final order that completely disposes of the case, or of a particular matter therein when declared by these Rules to be appealable. No appeal may be taken from:cralawlibrary (a) An order denying a motion for new trial or reconsideration; (b) An order denying a petition for relief or any similar motion seeking relief from judgment; (c) An interlocutory order; (d) An order disallowing or dismissing an appeal; (e) An order denying a motion to set aside a judgment by consent, confession or compromise on the ground of fraud, mistake or duress, or any other ground vitiating consent; (f) An order of execution; (g) A judgment or final order for or against one or more of several parties or in separate claims, counterclaims, cross-claims and thirdparty complaints, while the main case is pending, unless the court allows an appeal therefrom; and (h) An order dismissing prejudice;rbl rl l lbrr an action without

In all the above instances where the judgment or final order is not appealable, the aggrieved party may file an appropriate special civil action under Rule 65. (Emphasis supplied.) The remedy against an interlocutory order not subject of an appeal is an appropriate special civil action under Rule 65 provided that the interlocutory order is rendered without or in excess of jurisdiction or with grave abuse of discretion. Having chosen the wrong remedy in questioning the subject interlocutory orders of the RTC, petitioner's appeal was correctly dismissed by the CA. WHEREFORE, the petition for review on certiorari is DENIED, for lack of merit. The Decision dated September 9, 2008 and Resolution dated December 15, 2008 of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 85384 are AFFIRMED. With costs against the petitioner.SO ORDERED.

Page 11 of 14

4) A.M. NO. RTJ-08-2146 : November 14, 2008] (Formerly OCA-I.P.I. No. 07-2742-RTJ) MELY HANSOR MAGPALI,Complainant, v.JUDGE MOISES M. PARDO, Regional Trial Court of Cabarroguis, Quirino, Branch 31,Respondent. We pass upon the verified Complaint dated September 25, 2007 filed by MelyHansorMagpali (Complainant) charging Judge MoisesPardo (respondent judge, Presiding Judge, Regional Trial Court, Branch 31, Cabarroguis, Quirino) with violation of the Code of Judicial Conduct in the handling of Civil Case No. 659-2007 entitled "MelyHansorMagpali v. MoisesMagpali." The complaint originated from the civil case filed on June 12, 2007 by the complainant against her husband MoisesMagpali for support and alimony pendente lite. She alleged that she was initially discouraged when she learned that the case was raffled to the sala of the respondent judge because her husband and the respondent judge were friends. She decided, however, to give the respondent judge the benefit of the doubt, hoping that he would be sympathetic to her situation as an abandoned wife with no means of livelihood. The complainant further alleged that since the filing of the case and after the filing of her husband's answer dated July 23, 2007, the case had not been set for pre-trial or for a hearing on her prayer for support pendente lite notwithstanding her obvious need for support. The complainant also alleged that in one of her visits to the court to follow-up the status of her case, she spoke with a member of the court's staff (a certain Mr. Jose Enriquez) and with the respondent judge who inquired about the purpose of her visit. On learning that she is the wife of MoisesMagpali, the respondent judge allegedly became hostile and commented that she has no right to claim any property from her husband because these properties were acquired prior to their marriage. She explained that the properties were acquired during their marriage, while Mr. Enriquez told the respondent judge that the complaint was for support from her husband. This information elicited the remark from the respondent judge that the complainant has no right to claim support. The complainant interpreted this incident to be a manifestation of the respondent judge's extreme bias, partiality in her husband's favor, and pre-judgment of the case. The complaint lastly alleged that respondent judge had delayed the hearing of the case notwithstanding its urgency; in fact, the case had not been set for hearing since it was filed. The respondent judge filed on November 29, 2007 his comment to the complaint in compliance with the directive of the Office of the Court Administrator (OCA). He disclosed in his Comment that there are two (2) related cases involving the complainant: (a) a Support with Alimony Pendente Lite case filed by complainant against her husband; and (b) an Annulment of Marriage case instituted by MoisesMagpali against the complainant. The respondent judge denied the charge that he violated the Code of Judicial Conduct. To prove his point, he contended that: he had not issued any order or document in connection with either of the two cases showing his partiality or bias towards MoisesMagpali; the annulment case was scheduled ahead because the party asked for its scheduling, whereas the complainant did not in any manner request that her petition for support be scheduled for hearing; under Rule 18,

par. 1, of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, the complaining party should request for the setting of the case for pre-trial. The respondent judge likewise denied the remarks attributed to him by the complainant and submitted the affidavit of the Clerk of Court Officer-in-Charge who was present when he talked with the complainant. The affidavit clarified that the respondent judge did not utter the statements attributed to him. Finally, to convince the complainant of the absence of any bias against her, the respondent judge issued an Order inhibiting himself from handling the two cases. The OCA informed the Court that the case was already ripe for resolution in a Report dated April 24, 2008 signed by then Court Administrator Zenaida N. Elepao (now retired) and Deputy Court Administrator Reuben P. De la Cruz. The Report likewise presented a brief factual background of the case. The OCA recommended that the respondent judge be fined in the amount of P10,000.00 for gross ignorance of the law with a stern warning that a repetition of the same offense shall be dealt with more severely. The recommendation was based on an evaluation which reads: EVALUATION: A close examination of the records of this administrative case shows that there is no solid evidence to substantiate the complainant's allegation of bias and partiality against the respondent Judge. Bias and partiality can never be presumed. Bare allegations of partiality will not suffice in the absence of clear and convincing proof that will overcome the presumption that the judge dispensed justice according to law and evidence, without fear and favor (Chin v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 144618, August 15, 2003). Settled is the rule that in administrative proceedings, the burden of proof that the respondent committed the acts complained of rests on the complainant. The complainant must be able to show this by substantial evidence, or such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion, otherwise, the complaint must be dismissed (Adajar v. Develos, A.M. No. P-052056, [18 November 2005]). The basic rule is that mere allegation is not evidence, and is not equivalent to proof (Philippine National Bank v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 116181 [6 January 1997]). In this case, complainant failed to substantiate the allegation that the respondent Judge exhibited extreme bias and has already pre-judged her case. Other than her bare allegations, there is nothing in the records that would prove that the respondent Judge was hostile and made the remarks that she has no right to claim for support. Complainant could have gathered evidence to support the alleged bias or partiality of the respondent Judge. On the other hand, respondent Judge was able to submit an affidavit executed by Mr. Enriquez that no such remark was made or the cited incident actually occurred. On the whole, the evidence on record deals only with evidently self-serving statements of complainant vis - -vis that of the denial of the respondent Judge. However, respondent Judge should be sanctioned when he disregarded a fundamental rule. The New Code of Judicial Conduct for the Philippine Judiciary requires judges to be embodiments of judicial competence and diligence. Those who accept this exalted position owe to the public and this Court the ability to be proficient in the law and the duty to maintain professional competence at all times (Lim v. Dumlao, 454 SCRA 196, March 31, 2005). Indeed, competence is a mark of a good judge. This exalted position entails a

Page 12 of 14

lot of responsibilities, foremost of which is proficiency in the law. Once cannot seek refuge in a mere cursory knowledge of statues and procedural rules (Ualat v. Judge Ramos, 333 Phil. 175, December 6, 1996). Respondent Judge fell short of these standards when he failed in his duties to follow elementary law and to keep abreast with prevailing jurisprudence. His claim that the party did not in any manner request that the case be scheduled for hearing as provided under Rule 18, par 1 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, and that it should be the party who will ask an ex-parte setting/scheduling of the case for its pre-trial is not exactly correct. A.M. No. 03-1-09-SC, 16 August 2004 (Rule on Guidelines to be Observed by Trial Court Judges and Clerks of Court in the Conduct of Pre-trial and Use of Deposition-Discovery Measures) provides that within 5 days from date of filing of reply, the plaintiff must promptly move ex-parte that the case be set for pre-trial conference. If the plaintiff fails to file said motion within the given period, the Branch COC shall issue a notice of pre-trial. The respondent Judge should be conversant therewith. The case has not been set for pre-trial or at least for a hearing after the filing of the Answer dated 23 July 2007. He must know the laws and apply them properly. Service in the judiciary involves continuous study and research from beginning to end (Grieve v. Jaca, 421 SCRA 117, January 27, 2004). We concur with the finding of the OCA that the respondent judge is answerable for gross ignorance of the law. Indeed, we find that the respondent judge mishandled the complainant's case, mainly because of his lack of a full understanding of the procedural rules applicable to the case. Without doubt, respondent judge had been remiss in the performance of his duties by failing to keep himself updated on the current law, jurisprudence, and the rules of procedure. As we held in fairly recent administrative cases,1 a magistrate owes to the public and to this Court the duty to be proficient in the law and to be abreast of legal developments. The respondent judge failed to come up to this exacting standard and this, we cannot countenance. We approve as well the OCA's recommendation that a fine of P10,000.00 be imposed on the respondent judge. This level of fine stresses upon all the need to be legally proficient and competent, while taking into account the level of harm the judge's gross ignorance wrought on the complainant. WHEREFORE, premises considered, Judge Moises M. Pardo, RTC, Branch 31, Cabarroguis, Quirino is hereby FINED in the amount of P10,000.00 for gross ignorance of the law, with a STERN WARNING that a repetition of the same offense shall be dealt with more severely. SO ORDERED.

Cheryl caught Edward in a very compromising situation with the midwife of Chua Giak. After a violent confrontation with Edward, Cheryl left the Forbes Park residence on October 14, 1990. She subsequently sued, for herself and her children, Edward, Edwards parents, and Edwards grandparents for support. In a judgment rendered on January 31, 1996, the regional trial court ordered Edward and his parents to jointly provide P40,000 monthly support to Cheryl and her children, with Edward shouldering P6,000 and Edwards parents the balance of P34,000 subject to Chua Giaks subsidiary liability. Edwards parents appealed to the Court of Appeals. They argued that while Edwards income is insufficient, the law itself sanctions its effects by providing that legal support should be in keeping with the financial capacity of the family under Article 194 of the Civil Code, as amended by Executive Order No. 209 (The Family Code of the Philippines). In its Decision dated 28 April 2003, the Court of Appeals affirmed the regional trial court.The Court of Appeals ruled: The law on support under Article 195 of the Family Code is clear on this matter. Parents and their legitimate children are obliged to mutually support one another and this obligation extends down to the legitimate grandchildren and great grandchildren. In connection with this provision, Article 200 paragraph (3) of the Family Code clearly provides that should the person obliged to give support does not have sufficient means to satisfy all claims, the other persons enumerated in Article 199 in its order shall provide the necessary support. This is because the closer the relationship of the relatives, the stronger the tie that binds them. Thus, the obligation to support is imposed first upon the shoulders of the closer relatives and only in their default is the obligation moved to the next nearer relatives and so on The Court of Appeals denied the motion for reconsideration filed by Edwards parents, who appealed to the Supreme Court. On the issue of whether Edwards parents are concurrently liable with Edward to provide support to Cheryl and her children, the Supreme Court ruled in the affirmative but modified the appealed judgment by limiting liability of Edwards parents to the amount of monthly support needed by Cheryls children. According to the Supreme Court, Edwards parents are liable to provide support but onl y to their grandchildren: By statutory and jurisprudential mandate, the liability of ascendants to provide legal support to their descendants is beyond cavil. Petitioners themselves admit as much they limit their petition to the narrow question of when their liability is triggered, not if they are liable. Relying on provisions found in Title IX of the Civil Code, as amended, on Parental Authority, petitioners theorize that their liability is activated only upon default of parental authority, conceivably either by its termination or suspension during the childrens minority. Because at the time respondents sued for support, Cheryl and Edward exercised parental authority over their children, petitioners submit that the obligation to support the latters offspring ends with them. Neither the text of the law nor the teaching of jurisprudence supports this severe constriction of the scope of familial obligation to give

5) G.R. No. 163209, October 30, 2009 Cheryl married Edward Lim sometime 1979 and they have three children. Cheryl, Edward and their children lived at the house of Edwards parents, Prudencio and Filomena, in Forbes Park, Makati City, together with Edwards ailing grandmother, Chua Giak and her husband Mariano. Edward was employed with the family business, which provided him with a monthly salary of P6,000 and shouldered the family expenses. Cheryl had no steady source of income.

Page 13 of 14