Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Opinion Mamnoon Hussain

Hochgeladen von

Engr TariqCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Opinion Mamnoon Hussain

Hochgeladen von

Engr TariqCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mamnoon and the Lascelles Principles S Iftikhar Murshed Sunday, September 08, 2013 From Print Edition

The ways of providence are mysterious. It has unexpectedly raised Mamnoon Hussain, a political lightweight from Karachi, to the pinnacle. Tomorrow he will be sworn in as the twelfth president of Pakistan but, with the passage of the 18th Amendment of the constitution, he will wield no power. Two of his predecessors, Fazal Ilahi Chaudhry and Muhammad Rafiq Tarar, were also figurehead presidents mere sidekicks to the all-powerful prime ministers of their times. Pakistan is a land of a million myths and one of them is the belief that the 1973 constitution established unfettered parliamentary democracy in the country. But closer to the truth is that it was tailored to cater to the ambitions of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. In fact it was the 1956 constitution that introduced a genuine parliamentary system, and, after it was abrogated in 1958, the country underwent continuous political convulsions. But despite its flaws, the 1973 constitution has served as the basic law of the land for 40 years and this is reason enough for it to be further strengthened and continuously modified if it is to eventually establish a parliamentary system. But in these four decades it was distorted and disfigured by autocratic presidents and prime ministers. It is these mutilations that the 18th Amendment claims to have rectified. The first lines of the Statement of Objects and Reasons, signed by Senator Raza Rabbani, reads: The Constitution of 1973 was not implemented in letter and spirit. The democratic system was derailed at different times. The non-democratic regimes which came to power at different times centralised all authority and thus altered the structure of the constitution from a parliamentary form to a quasi-presidential form of government through the 8th and the 17th constitutional amendments... Last week, at a dinner he hosted for the media, President Asif Ali Zardari said that he would be handing over the baton to his successor with a sense of fulfilment. He had surrendered his powers to parliament and the fortress of democracy had been made impregnable. PPP stalwarts never tire of boasting that their party had restored the 1973 constitution but what they do not readily concede is that the 18th Amendment retains several of the harmful modifications introduced by previous leaders. Constitutional experts are convinced that the basic law enacted in 1973 established a prime ministerial dictatorship and a highly centralised federation. They contend that parliamentary democracy is founded on checks and balances. Central to this is a president powerful enough to restrain an autocratic prime minister but yet not so powerful as to be able to subvert the constitution. This means that the prime minister must also have sufficient powers to foil such attempts by the president to abrogate or suspend the basic law of the land. But Bhutto was obsessed with power and motivated by monstrous ambitions. This was what prompted Mian Mahmud Ali Kasuri, the chairman of the Constitution Committee and the law minister to resign in October 1972. Kasuri, a recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize who served in the Stockholm War Crimes Tribunal established by Bertrand Russell, was committed to a parliamentary form of government with its attendant checks and balances. He saw through Bhuttos game and refused to be a party to it. The constitution that was promulgated the following year vested all powers in the prime minister and

reduced the president to a pathetic figurehead. This structural imbalance, which sticks out like a sore thumb, can be rectified by modifying the 1973 constitution in accordance with those of the major parliamentary democracies. They are all in conformity with the vast corpus of legal opinion recorded by the worlds foremost constitutional experts. Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and India, for instance, recognise the right of the head of state to: (i) be consulted; (ii) demand information; (iii) select a prime minister if elections yield a hung parliament; (iv) dissolve parliament, and; (v) dismiss the prime minister as a last resort if he betrays the trust reposed in him on issues of pivotal national importance. From this, constitutional experts derive the opinion that the head of state is also empowered to dissolve parliament but without dismissing the prime minister thereby compelling him to seek a new electoral mandate. Correspondingly, the prime minister is within his competence to request, but not demand, dissolution. The acceptance or rejection of such a request is the prerogative of the head of state. This principle was enunciated in a letter from a mysterious Senex which was published by The Times of London on May 2, 1950. It has been cited since then in every major work of constitutional law. The author eventually turned out to be none other than Sir Alan Lascelles (1887-1981), Private Secretary to King George VI and, later, Queen Elizabeth II. The Lascelles Principles, as the contents of the letter came to be known, affirm: It is surely indisputable (and common sense) that a prime minister may ask not demand that his sovereign will grant him a dissolution of parliament and that the sovereign, if he so chooses, may refuse to grant this request. Lascelles further explains that no wise sovereign...would deny a dissolution to his prime minister unless he were satisfied that: (1) the existing parliament was still vital, viable, and capable of doing its job; (2) a general election would be detrimental to the national economy; (3) he could rely on finding another prime minister who could carry on his government, for a reasonable period, with a working majority in the House of Commons. A prime minister whose request is rejected has the option to resign and thereby force an election. On the question of the dismissal of the prime minister all constitutional authorities are unanimous in their opinion that the head of state in a parliamentary system has such powers. However in England it has not been exercised by the Crown since 1783. Professor Geoffrey Marshall (1929-2003), who was one of the two British constitutional experts (the other being Lord Blake) regularly consulted by the Queen, was convinced that: Dismissal would be appropriate if a government, by illegal or unconstitutional administrative action, were to violate some basic convention of constitutional behaviour. In entrenched parliamentary democracies the most dramatic application of this norm was the dismissal of the Australian Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, on November 11, 1979, by the Governor General, Sir John Kerr. But the ensuing constitutional crisis the worst the country has ever known was not allowed to destabilise the system. Reason triumphed over emotions, and years were spent in talking through issues under the mechanism of an All-Parties Constitutional Convention. Eventually, in August 1999, the joint select committee of the Australian parliament submitted its Advisory Report on Constitution Alteration (Establishment of Republic) Bill 1999 and Presidential Nominations Committee Bill, 1999. At issue was a determinati on of what powers the president should have in the envisaged republic. The proposal was rejected in the 1999 referendum by 55 percent of the voters and it was decided to

retain the existing system without altering the reserve powers of the governor gen eral. The clumsily worded formulation in paragraph 4.10 of the Advisory Report Bill reads: It is generally accepted that there are only four powers; namely, the power to appoint a prime minister, the power to dismiss a prime minister, the power to refuse to dissolve parliament and the power to force a dissolution of parliament. The reputed scholar A G Noorani, whose writings have prompted this article, believes that for the transformation of Pakistan into a Westminster-type parliamentary democracy, all that is required is a modification of the 1973 constitution by: (i) restoring the powers of the president as embodied in the 1956 constitution, and; (ii) codifying the conventions of the parliamentary system into the basic law to prevent the misuse of power by the president and the prime minister. But this requires political maturity blended with visionary leadership which has never been in evidence through the crisis-saturated history of Pakistan. There is no desire to bring the 1973 constitution in conformity with the norms of parliamentary democracy and Mamnoon Hussain will remain a figurehead president. The writer is the publisher of Criterion Quarterly. Email: iftimurshed@gmail.com

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- World Constitutions PDFDokument534 SeitenWorld Constitutions PDFSamreen Inayatullah60% (5)

- Constitutional Law NCA SummaryDokument59 SeitenConstitutional Law NCA SummaryKC Onuigbo100% (11)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Haythornthwaite - The English Civil War 1642-1651Dokument160 SeitenHaythornthwaite - The English Civil War 1642-1651Paul Gross100% (8)

- Legal System in SingaporeDokument28 SeitenLegal System in SingaporeLatest Laws TeamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adequate Level of Data Protection' in Third Countries Post-Schrems and Under The General Data Protection Regulation, Paul RothDokument20 SeitenAdequate Level of Data Protection' in Third Countries Post-Schrems and Under The General Data Protection Regulation, Paul RothJournal of Law, Information & Science100% (1)

- Annual Development Programme: Board of RevenueDokument15 SeitenAnnual Development Programme: Board of RevenueEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annual Development Programme: Auqaf, Hajj, Religious & Minority AffairsDokument14 SeitenAnnual Development Programme: Auqaf, Hajj, Religious & Minority AffairsEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

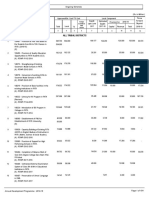

- Annual Development Programme: FinanceDokument5 SeitenAnnual Development Programme: FinanceEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geo Tagging of Monitored Schemes in Mergerd Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 2019-20 Sector Nomenclature/sub Head Cost - M Adp No Code No DistrictDokument6 SeitenGeo Tagging of Monitored Schemes in Mergerd Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 2019-20 Sector Nomenclature/sub Head Cost - M Adp No Code No DistrictEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADP Book 2018-19Dokument154 SeitenADP Book 2018-19Engr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Development Bank Independent Evaluation Department: Sector Assistance Program EvaluationDokument154 SeitenAsian Development Bank Independent Evaluation Department: Sector Assistance Program EvaluationEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report Summary of GZD-Cammand Area (Edited On 8-7-2020)Dokument25 SeitenReport Summary of GZD-Cammand Area (Edited On 8-7-2020)Engr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solar Water Pumping System in Isolated Area To Electricity: The Case of Mibirizi Village (Rwanda)Dokument13 SeitenSolar Water Pumping System in Isolated Area To Electricity: The Case of Mibirizi Village (Rwanda)Engr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asian Development Bank: Project Performance Audit ReportDokument59 SeitenAsian Development Bank: Project Performance Audit ReportEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6th Class HistoryDokument14 Seiten6th Class HistoryEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Great Gift PDFDokument32 SeitenA Great Gift PDFEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation and Monitoring of Learning and AssessmentDokument8 SeitenEvaluation and Monitoring of Learning and AssessmentEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solar Pump Application in Rural Water Supply - A Case Study From EthiopiaDokument7 SeitenSolar Pump Application in Rural Water Supply - A Case Study From EthiopiaEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prevailing Energy Crisis in PakistanDokument8 SeitenPrevailing Energy Crisis in PakistanEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Cut Keys & Run CommandsDokument5 SeitenShort Cut Keys & Run CommandsEngr TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fnmisuri The StuartDokument16 SeitenFnmisuri The StuartSimiuțiu Ilie100% (1)

- History Paper 2 Aminath Saany NaseerDokument9 SeitenHistory Paper 2 Aminath Saany NaseerCrina PoenariuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lire L'intégralité Du Statement de Roshi BadhainDokument3 SeitenLire L'intégralité Du Statement de Roshi BadhainL'express MauriceNoch keine Bewertungen

- US v. Bull 15 PHIL 7Dokument21 SeitenUS v. Bull 15 PHIL 7AnonymousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determinants of Foreign PolicyDokument33 SeitenDeterminants of Foreign PolicyBaaniya NischalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Securency's Nigeria Deal, InvestigationsDokument14 SeitenSecurency's Nigeria Deal, InvestigationsZaneta2009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Procedure of Appointing and Electing Officials: Appointed OfficialDokument3 SeitenProcedure of Appointing and Electing Officials: Appointed OfficialrbNoch keine Bewertungen

- April 08 Dawn Opinion With Urdu TranslationDokument12 SeitenApril 08 Dawn Opinion With Urdu TranslationShahabjan BalochNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of The British ConstitutionDokument7 SeitenDevelopment of The British ConstitutionOmkar ThakurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exhibit A Legal Position On Commonwealth Sovereignty of Her Majesty'S DominionsDokument2 SeitenExhibit A Legal Position On Commonwealth Sovereignty of Her Majesty'S DominionsMarc BoyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compare The Constitutional and Democracy of Britain and China (Autorecovered)Dokument8 SeitenCompare The Constitutional and Democracy of Britain and China (Autorecovered)P. VaishaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Document: Bangsamoro Organic LawDokument47 SeitenFull Document: Bangsamoro Organic LawiagorgphNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shiv Kumar Chadha Case PDFDokument12 SeitenShiv Kumar Chadha Case PDFNarayandas SanjayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Russian Law Back in GeorgiaDokument2 SeitenRussian Law Back in GeorgiaReginfoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TZS 12 Feb 2012Dokument2 SeitenTZS 12 Feb 2012Kamzalian TomgingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edi GeoDokument15 SeitenEdi GeoJtutorialesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parliamentary Debate: Nadya AyuDokument29 SeitenParliamentary Debate: Nadya AyuNadya Ayuning WuryantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Parties Class 10 Revision WorksheetDokument5 SeitenPolitical Parties Class 10 Revision Worksheetvprogamer06Noch keine Bewertungen

- Serengeti Advisers - Media Report October 09-1Dokument8 SeitenSerengeti Advisers - Media Report October 09-1serengeti_advisersNoch keine Bewertungen

- 201335692Dokument72 Seiten201335692The Myanmar TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Level Law SAMsDokument80 SeitenA Level Law SAMscase com100% (1)

- 1000 Companies To Inspire EuropeDokument78 Seiten1000 Companies To Inspire EuropeLe Monde100% (2)

- Checking of Submitted Periodic Safety Update ReportsDokument3 SeitenChecking of Submitted Periodic Safety Update Reportsdopam100% (1)

- Amity University Haryana: Assignment of Constitutional LawDokument9 SeitenAmity University Haryana: Assignment of Constitutional LawAnubhav SinghNoch keine Bewertungen