Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Siebel Tastepanel

Hochgeladen von

Antonio ImperiCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Siebel Tastepanel

Hochgeladen von

Antonio ImperiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Taste Panel Pitfalls

By J. J. OLSHAUSEN

J.J. Olshausen is Director of Technical Service, I. E. Siebel Sons' Company, Inc., Chicago. This paper was presented in greater detail at the Joint Convention o f Districts Venezuela and Caribbean, held in Caracas in February, 1969. The paper was also presented at a meeting of District Western Canada, held in Banff, Alberta, in July, 1969. Included here is only Part I of this paper which was presented in two parts. Part II gave illustrations and specific examples from actual taste-panel work. Details of this part of the work may be obtained by writing to the author.

www.probrewer.com

www.siebelinstitute.com

A great deal has been studied, written, and published about taste-testing, and a tremendous amount of suc cessful effort is continually put forth in the system atization of odor and flavor evaluations for all types of food products, as a matter of quality control and as checks on flavor uniformity and improvement, for the ultimate benefit of the consumer. For malt beverages such as beer, many types of tests are in use : tests for difference, tests for similarity, twoglass tests, three-glass or triangular tests, preference tests, etc. Statistical significance ratings worked out in the well-known Bengtsson tables (published in E.B.C. "Analytica") and expressed by 1, 2, or 3 stars, are an additional refinement where taste comparisons are in volved. The present paper will not deal with any of these various approaches, but will rather attempt to present certain aspects and their pitfalls. Smelling and tasting have become a science, but a science dealing with human physiology, and humans do not have built-in spectro photometers or other measuring devices. Plainly self-evident as this is, there are occasions when there is merit and purpose in bringing into focus facts which are so obvious that ordinarily it would seem pointless to dwell on them. Such are the facts that the main pillar of our brewing industry and the intrinsic source of success of the individual brewery, in the final analysis are not governed by such factors as the ana lytical compositions of your beer or the source, type, and price of your brewing materials, nor indeed by any units or components that are measurable and expressable in figures in the laboratory, but exclusively by the utterly subjective, imaginational, easily influenceable, often mood-oriented, and sometimes plain fickle reac tions of several million thirsty mouths whose owners pay good money to gain a sustained flavor sensation which can never he expressed in chromatographic or other figures. This we all know. And because of this obvious truth, members of the technical personnel in a brewery gener ally form taste panels whose job it is to keep an eye on flavor quality, or more succinctly, that kind of beer flavor which is desired because it sells best. Right here, the qualifying words, "sells," in relation to quality, in volves a typical pitfall I may discuss first. Variability of Organoleptic Acceptance Patterns A taste panel can judge the acceptability of a beer purely on the basis of the traditional concepts of purity, pleasurable flavor balance, and absence of defects ; or the panel can judge beer mainly in adaptation to the preference pattern of its consumer territory regardless

of flavor traits which, although perfectly clean and normal as such, are not desired in a different territory, or even regardless of some chronic defect it may have, so long as it sells. Let me give you a typical example i nvolving a defect. In the state or province of XYZ, a regional brewery produces a beer which has a slight musty cellar taste (Hausgeschmack), perhaps coupled with diacetyl in some brews or bottlings. This fault, which is subject to criticism by any discriminating taster, has been in existence for a long time, perhaps 20. or 30 years, and has become a characteristic so deeply i ngrained in the consumer's association with this beer that he is not only not conscious of it but simply does not recognize the defect for what it is, since he is used to it. It has almost become something of a trademark for that particular beer. Why, if the brewery were in a position to make a technically clean, flawless product out of this beer overnight, it is entirely conceivable that a certain percentage of its regular clientele, instead of expressing enthusiasm, will shift its loyalty to another brand because their favorite local brand has "changed." To my recollection, there actually have been experiences of this nature. This immediately raises the question : What shall this brewery do ? Continue brewing musty beer or strive for technical improvement ? What should a re sponsible taste panel recommend ? Endorse the musty beer as acceptable or express justifiable criticism em phatic enough to give the brewer sleepless nights It is my considered opinion, in this situation, that a taste panel by all means has the duty to express its misgivings, but at the same time to cooperate (diplo matically!) with the technical heads of the brewery in finding ways and means to get rid of the abnormality, because any chronic defect, after all, can become inten fied as time goes on and can lead to the day where re gardless of local consumers' "loyalty," the beer is recognized as unappetizing, and economic disaster re sults. We also have had experiences of just this kind. A comparable situation, in a way more problematical than the case of quality defects, involves the evaluation of normal flavors in beers originating from different geographical areas, which in their own territory are the only accepted ones, but very easily can strike an un accustomed taste panel as anywhere from "unusual" or peculiar to outright objectionable, since under the commonly followed "blindfold" testing conditions, the panelist subconsciously will think he is tasting a beer of his own accustomed surroundings with which something went wrong. For example, taste impressions which we i n the United States would classify as "malty," spicyburnt, or syrupy-often associated with oxidation in American beers-in reality may indicate nothing of the sort, but are an intentional and normal characteristic

in a different part of the world. Even a highly experi enced taste panel will hardly be able, under the custom "ablindforcyts,eharlyfind unbiased judgment on beer samples originating from such widely varying regions as, say, Philadelphia, Seattle, Holland, Venezuela, Bolivia, or South Aus tralia. A perfectly normal and fresh Australian beer, which typically possesses a heavy-flavored, bitter-sweet, almost sucrose-like, as well as very hoppy and spicy character, will confound the senses of a taste panel in Milwaukee or Chicago if not geared to its peculiarities. Yet this is precisely what a consulting laboratory often is confronted with. For this reason it is good practice to announce to the panel beforehand that a certain glass poured for testing and identified by its number in a sequence contains a foreign beer, perhaps even giving its geographic origin, or indeed for that matter, an ale as opposed to a lager beer. Continued experience with foreign beers can "precondition" a taste panel into "anticipating" a certain flavor impression which, if an alerting announcement is not made, may well invite un fair and unrealistic responses. This brings us to a fundamental consideration. What is the purpose of a taste panel and to what extent can it be looked upon as a panel of experts? The answer to this question depends on whether the panel functions i n a brewery and is composed of brewery employees, or consists of an independent group of persons as in a consulting laboratory like ours. Either of these groups has an advantage over the other, and at the same time is at a certain disadvantage. Brewery Panels vs. Consulting Panels A taste panel in a brewery has the advantage of knowing its own brand so well that any sudden devia tion from the usual, desired flavor in one brew or tank can be recognized with relative ease and probably can be straightened out if need be. There is the added advantage that the usual taste panel work operating with glasses having been poured with traditionally limited quantities, can be supplemented with larger-scale tests. Any panel member in the brewery generally can take several bottles home to see how much he may really enjoy the contents and how they agree with him. He, like any regular consumer, thus judges by drinking, not by sipping, which actually is a pretty important aspect of taste-testing, often overlooked. Furthermore, a brewery panel is in a position to have daily taste contact with competitive brands and, so, has a valuable opportunity to gauge and adjust its own brand in taste quality, following market and popularity trends. On the other hand, this very closeness to one's own brand has the disadvantage of risking a certain dulling, or even loss, of keenest taste perceptions, potentially resulting over a period of time in immunity toward

gradual, subtle changes in beer character that are not desirable and may eventually be reflected in a change of consumer acceptance in your territory. An outside panel like ours again has the advantage of wide experience in judging all kinds of brands of beer and ale. Since an outside panel has no restrictively close association with any one brand (and its com petitors), taste evaluations are generally free of involuntary bias or locally induced loss of taste acuity occasioned by the constant "closeness" referred to earlier. This circumstance builds up and enhances reputation and trust while at the same time imposing on the panel a tremendous responsibility, especially if the panel's verdict is meant to guide the brewer. The disadvantage to which an outside taste panel is subjected relates to various factors. As pointed out before, an outsider cannot always gauge territorial preferences but is principally guided by his own de tached impressions. This can cause a problem. If I happen to thoroughly dislike a type of beer merely because it registers with my palate as thin, bland, dry, and almost tasteless, but represents a big selling product among a growing and highly appreciative portion of the consuming public (I might think in this instance of ex tremes such as currently popular diet beers or similar products). I would not be justified in expressing my sweeping rejection to the brewmaster who listens to my "expert" judgment, but I must ask myself, "How should the beer he judged from the standpoint of that particular consumer for whom this brand was formu l ated and brewed ?" Then there is the disadvantage that the outside taste panel usually performs its taste test with relatively li mited quantities of beer, without recourse to expand i ng the evaluation by taking some bottles home. Even if sufficient sample material is available, such leisurely expansion of the test is impractical (with rare excep tions where specifically requested), simply for lack of ti me and because of the volume of beer that would have to be consumed-not to mention the fact that a good taster is not necessarily an eager beer drinker in this context. Flavor Changes and Container Variations The overwhelming bulk of all taste panel work is mechanically conducted in the traditional way, namely, a certain number of beer samples whose identities are not disclosed to the panel prior to the test, are poured i nto glasses by a nonparticipating person and presented to the panel for evaluation and/or comparison, which usually is executed in some written form. Pitfalls in this most common of all tasting procedures are so nu merous I could not cover their multitude in many hours of talking. Here, I should make it plain that the great

variety of purely procedural factors such as color and type of glass, testing temperature, time of day, and en vironmental conditions, which vary somewhat from panel to panel, are not intended to he a subject within the framework of this paper. What I want to bring out is the physical, attitude-conscious, and psychological reaction of the taster in this traditional taste test as it is performed the world over by both brewery taste panels and outside panels of consultants ; also, how it can differ from reactions toward the same brands of beer under more informal conditions of leisurely con sumption. Here is an example : In our regular taste panel which might consist of nine persons on a given day. a clear majority of 7 to 2 find a beer sample to have a distinctly yeasty, sulfury, and sharp odor and a similarly objectionable taste. Thereafter, in the desire to estab lish whether this impression is reproducible, an informal double-check is made. Several freshly poured glasses of the same beer are each presented some hours later (at a desirable hour and not immediately after lunch or a coffee break) to the same persons who participated previously. These are not informed of the beer's iden tity. They are requested to pass judgment. In this second test, none of the objections raised in the first taste are repeated. The beer is given a perfectly clean bill of health. This kind of experience, which occurs every once in a while, may, of course, reflect a frailty of the human palate. But it may also suggest the interesting possi bility that one bottle content can differ from the other, even though both came from the same filler and the same bottling run. In view of its annoying implications, we would like to dwell for a few minutes on this problem of variations from bottle to bottle. Of course, to speculate on bottle variations every time a panel member contradicts himself can be made into a pretty excuse for human shortcomings. If the panelist reacts favorably to a beer today and unfavorably to the same beer from a different bottle tomorrow, he might claim "variations among bottles" i n order to hide his own inadequacy. So let us dismiss this "easy way out." Also, let us dismiss the obvious speculation on the possibility of varying air contents in the headspace-unless, of course, there are indications to this effect on the basis of actual tests. However, our experience has been-in my opinion, beyond the shadow of a doubt-that there are more variations among bottles than may commonly he believed. Strictly speak i ng, a bottle variation can be proven only if within one taste-panel session, glasses poured from different bot tles of the same brand, tank, and filling date are exchanged by those participants whose appraisals differ radically. In our taste panel, we generally have two groups of participants, one group lined up on the east

side and the other on the west side of the room. As suming the standard 12 ounce (approx. 360 cc.) con tainer size, the east group receives the contents of one bottle, and the west that of another bottle. If eastsiders and westsiders express significantly different opinions on their return forms, glasses between east and west can profitably be exchanged, the situation discussed, and a verbal agreement reached to the effect that differ ences do exist and are so obvious that they cannot he denied. Not only that, but on some occasions when glasses are exchanged, a difference in color has been observed (if opaque glasses are used, the respective contents then can simply he poured into clear glassees for color com parison). Just what causes the color variation is beside the point in this context. What matters is that it fur nishes the ultimate proof of undeniable bottle-to-bottle variation. In our taste panel, we experience this about once or twice every year. Although the immediate exchange of glasses is the only true proof, there are other situations which can he taken as almost as good a proof for such differences. This occurs, not infrequently, when a beer sample ship ment is to be retasted after several weeks or months of shelf storage for the purpose of evaluating its "flavor stability." As a typical example taken from our long-standing practice, a beer sample tasted at the time of receipt is judged in the most favorable terms and, by our special numerical scoring system, receives a high rating. After 30 days of shelf storage, the same beer is rated poorly, having developed a dull, bready, or "burnt" oxidation taste. Its flavor stability obviously appears to be very mediocre. After another 30 days of shelf storage, the very same is found to be perfectly normal and fresh, almost as good as it was two months ago, this time again inviting a high rating. This reversal evidently does not make sense because beers, although they sometimes become mellower and smoother as the days pass, usually do not get "better," certainly not fresher after several months, once they are oxidized. There was no change in the composition of the taste panel, and the opinion each time was almost unanimous. Now, one or two persons can be wrong or have an off day, but it is difficult to assume that an entire panel of perhaps ten experienced tasters can all be so wrong at the same time, such as indicated at the 30-day in terval in the above example. In this case, there is good substance in speculating that certain bottles withstood flavor deterioration better than others, perhaps due to the preservation of some intramolecular bonds necessary to perpetuate the quality of subtle flavor substances in the beer. Although there is no "proof" of bottle varia-

tions as in the exchange of glasses, one will readily agree that everything points to such a contingency. Significance of Individual Acuities In the example just given, it was mentioned that there was no change in the composition of the taste panel. This reference opens up some noteworthy vistas i nvolving pitfalls of a special kind. We can talk only of our own panel, but inasmuch as we are there to serve the brewing industry, that is you, we know you will be able to appreciate the following. (Besides, you may well have had the same experience.) judges of beer flavor can be good or poor, reliable or unreliable. There probably is no such thing as uni versal excellence embodied in any single taster. The best training of any taster can only go so far in sharpen ing his or her acuity, just as the best training of an athlete will not make him perform beyond his natural resources and limitations. However, there are tasters who are positively uncanny in repeated blindfold recog nition of certain flavors, though they may be absolutely i ncapable of distinguishing other types of flavors. We are able to give you some striking examples. For instance, one problem besetting breweries in certain areas and at certain times is the development of an irregularity known as a phenolic flavor which is very disagreeable. Sources of this defect can be water pollu tion by industrial wastes, certain bacterial developments on activated carbon filter beds, and others of problem atical origin. Not all persons are able to recognize the defect in the taste, and we know of pretty strong, argu mentative disagreements between different taste panels regarding the presence or absence of a phenolic taste in a given beer. In our group we have a limited number of panel members who invariably recognize phenolic flavors, with excellent reproducibility in repeated "blindfold" tests, whereas other participants might refer vaguely to an "odd" or foreign character of no partic ular magnitude, and others again are absolutely immune -so immune that they are apt to express the most favorable comments on the beer in question. You can i magine what it can mean if our best phenolic taste specialists are absent for some reason-traveling or ill -and are replaced by tasters whose specific acuity lies in other directions. It actually suggests that certain tasters in certain circumstances are indispensable. This remarkable faculty, or superiority if you will, of some individuals over others in certain areas of flavor per ception, obliges us, in a wider sense, to appreciate the need for adopting the following general guideline in taste panel work : In coordinating the individual opin ions expressed in a taste panel for a given beer, the final arbiter who eventually is to characterize the beer iii terms that are supposed to mirror a realistic cross-sec tion of the panel as a whole, should be well acquainted with each individual taste panel member, his forte and

his shortcomings, his susceptibilities and idiosyncrasies. The taste impressions of one individual whose acuity i n one certain area is acknowledged sometimes can weigh more than the reactions of any number of his fellow panelists. Conflict of Responses Here we would like to describe one of the most diffi cult situations with which a taste panel can be confronted. With respect to abnormal or off tastes and odors, there is hardly anything so baffling and exasper ating as diacetyl. Speaking only of tasters who are susceptible to this irregularity, we have seen again and again that a diacetyl character can disappear with un believable rapidity. Shortly after pouring the glasses, one sample among several may impart the strong, un mistakable odor and flavor of diacetyl. It is conscien tiously recorded by the panelist. But after a while, perhaps only five minutes later and still before the termi nation of the taste-panel session, the same beer is retasted out of curiosity, as an extra check, and is found to be completely free of the defect. If this experience were the rule, one could "live with it." One could always explain that diacetyl is a labile compound apt to dissipate soon and disintegrate into tasteless com ponents within minutes. But the fact is that the experi ence is not the rule. In other instances, diacetyl remains for any length of time. According to current knowledge, the phenomenon can be explained by the potential existence of a precursor produced during fermentation and presumed to be alpha-aceto lactic acid, possibly also 2, 3-butane-dial and its immediate oxidation product, acetoin. The com bined effect of heat, as in pasteurization, and whatever oxygen is present, transform the precursor into diacetyl. If sufficient precursor is available, the contact with oxy gen when pouring the beer, or upon stirring air into the glass when rotating it, can produce such quantities of diacetyl that it is observed organoleptically for a short ti me. Then it tends to be expelled and disappears from the beer with the release of CO2 gas, if the precursor is used up by now. If sufficient precursor is still available, a constant level of diacetyl will continue to make itself felt in odor and taste and will not disappear in a few minutes at all. This is an exasperating and dis concerting aspect in taste-panel work, because the most i nterested party, the practical brewer, is apt to be thor oughly confused when he gets a report from the taste panel which is so conflicting that it reminds of a magi cian's catch phrase, "Now you see it, now you don't." Almost equally disconcerting is a situation where a beer sample possesses a peculiarity which is voted both good and bad. Generally, this relates more to odor than taste. One or more members of the taste panel may be in agreement that a particular odor has an abnormal,

perhaps medicinal or otherwise objectionable character, which logically downgrades their opinion. In the same panel, equally qualified tasters make it a point to empha size impressions of a fine, fresh hop aroma. Quite ob viously, both parties experience one and the same sen sation, whatever it is, and find it sufficiently prominent to record it; they only differ in their opinion as to whether it is pleasant or unpleasant. There is no ques tion but that such a beer sample does have some dis tinctive property, possibly a mixture of aroma-produc i ng components, but a property which causes entirely opposite reactions in different individuals. And it seems noteworthy that in cases of this kind, the pleasant one of the two opposite sensations happens most frequently to be hoppiness. Quoting typical comments from actual taste panel work, here are a few interesting juxta positions

tasted yesterday when you did not find anything re motely resembling this bitter character. The experience just described can also relate to other basic palate impressions, like sweetness or astringency. There are days when "everything tastes bitter" or sweet, etc. It is almost futile to speculate on the causes for these strange variations which probably many of you have experienced. Of course, we all know that there are disabling conditions that may cause us to have mislead i ng and wrong impressions such as perhaps a cold or some other physical indisposition numbing the taste buds and the olfactory powers. Barring such obvious conditions as these, we may perhaps look for psychological or emotional factors we are not really conscious of but which at times seem to influence our physiological reactions and apparently can affect nose and mouth. If we have had a pleasant experience, the day is bright and emotionally sunny, our mood is friendly and we are given to tolerance. We tend to minimize nega tive impacts and feel generous and will be inclined to express praise rather than criticism. If we are worried or irritated and have had a bad experience, the day is emotionally gloomy, our mood is apt to swing to the negative side and we are prone to withhold praise and express criticism. In our taste panel there is an occa sional little joke that when a participant rates all beer samples highly he is in a "good mood" and vice versa. Speaking specifically of bitterness and sweetness, it is not at all ludicrous to submit that a certain combination of emotional factors will cause all taste perceptions to be bitter or less agreeable, whereas a different set of emo tional factors might accentuate sweetness and more agreeable sensations on the tongue and palate. This cer tainly does not allow for the more or less amusing gen eralization that on bad days everything tastes bitter and disagreeable and on good days everything tastes sweet and good. On the contrary, when we are in the hap piest of moods, we just as well are able to detect and even magnify the most objectionable flavor character istics, whereas on the gloomiest of mornings, we carry the torch for all the beers it is our duty to judge. But it does mean that our physiological reactions are not im mune to the subtle influence of hidden emotional patterns within ourselves from one day to another which very likely create some particular chemical arrangement i n our physiological, and specifically, organoleptic re sponses.

To formulate a correct and fair appraisal in the face of such "expert" contradictions is plainly a hit-or-miss proposition, and next to impossible. [t is like being at an unmarked road fork where you don't know which fork to take. Involuntary Proclivities Finally, let me describe a situation which probably is not unfamiliar to you. Supposing you are presented with four or five samples of beer whose identities are not disclosed but which are known to he of different origin. They are properly poured into glasses at the proper temperature, at your customery hour of the day. The first sample leaves a strong, lingering bitterness in your mouth, sufficient for you to object. You prob ably record this impression in whatever written form your panel uses. The second sample also leaves a linger i ng bitterness, again sufficiently strong for you to take issue with it. You begin to assume that these two samples are perhaps related somehow, maybe a "pair," or simply that you experienced a "carry-over" from the first to the second beer. Then you start tasting the third sample. This sample tastes equally bitter and you begin to wonder, because in the past you rarely found all this bitterness in your daily panel work. When the fourth sample hits your palate in just about the same way, and perhaps even the fifth, you will be bewildered. When the identities of the beers and the recordings of your fellow tasters are disclosed, you are surprised to find, not only that your colleagues detected no particular bitterness, but that the samples were the same ones you

PART II FIGURES 1 to 6, relating to PART II, are located at the end of the text In relation to the subject matter treated in PART I, and as a good means of demonstrating certain human responses in graphical form, the following pages describe our own standard taste panel record method, and its utilization. Each panel member receives a blank record form as illustrated in FIGURE I. ** This form provides for the evaluation of up to 7 beer samples at a time, indicated by the vertical columns, numbered from 1 to 7. A descriptive terminology of taste impressions appears in the left vertical column. Opposite of each term is a space for each beer sample, arranged horizon-

tally, to be filled in by the taster. These spaces contain four dots each and, in addition, in each of the four upper spaces a circle appears among the dots. In using this form the taster marks a cross through one of the dots or circles in the space chosen, to express his opinion, for example as shown in FIGURE 2. These markings are made by the panelist in accordance with the intensity or quality of the taste perception. The taster is under obligation to mark the first four horizontal spaces for

**

This is the latest, improved record form. A similar, older record blank as well as a detailed and descriptive explanation of the entire procedure including the preparation of the "Taste Pattern Chart", which in the present paper is duplicated in condensed form, was published as a separate paper in the BREWERS DIGEST, June 1961, and in SIEBEL CONTRIBUTIONS # 39, July 1961 by J. J. Olshausen.

every sample, as shown in FIGURE 2, whereas the marking of all other taste categories is optional. The reason for this requirement is that the first four indicated properties (degrees of freshness, body fullness, flavor fullness, and smoothness, or their opposites), which are of general or more or less "basic" nature, are usually applicable to every beer. In the first four horizontal spaces just referred to, the position occupied by the circle is to indicate an "average" condition. A mark to the left of the circle indicates the corresponding taste impression shown in the direction of the arrow pointing left, and a mark to the right indicates the opposite taste im pression in the direction of the arrow pointing right. (For "Stale" vs. "Fresh", there is no average in the usual sense since a beer cannot be fresher than fresh, or unoxidized. Hence, by common logic, the circle should really be at the ex treme right. The reason there is still a dot to the right of the "average" circle is to provide for "overly fresh", "green" or possibly worty tastes). Below these four general characterizations, and following a space for odor perception, the taste report form shows detailed and specific flavor categories, phrased and grouped in a certain logical order. Roughly, the upper portion of the listing comprises more or less normal taste perceptions, whereas the lower portion shows taste abnormalities. optional. The intensity of each taste perception is indicated by marking one of the four dots in that category. The first dot to the left indicates a faint or fleeting impression, the second dot a slight but well noticeable perception, the third Marking of any of these specific items is

dot a moderately strong impression, and the fourth dot a very strong impression. Random examples are shown in FIGURE 2. In the example, the panelist marked Beer #1 as normally fresh, on the flavorful side, smoother than average and having a rather intense hop character (third dot) of nice quality. A hoppy odor and a moderate afterbitter also are re-

corded. In Beer #2 a slight but not particularly offensive mustiness is marked. Beer #4, in the opinion of this panelist, is badly oxidized (top line, dot farthest to the left) and imparts a very strong diacetyl flavor. Beer #5 is slightly yeasty, and "green" or overly fresh (top line, fifth dot). At the bottom of each vertical column the respective beers are rated according to a numerical scoring system illustrated in FIGURE 3, which will be selfexplanatory. In FIGURE 2, Beer #1 is rated highly (+3). Beer # 2 is not the best, but acceptable and rated conservatively (+1). Beer #3, being slightly oxidized and "bready" as well as slightly harsh, is accorded a neutral mark (0). Beer #4 received the lowest possible mark of -4, and Beer #5 is rated almost as good as Beer #1 (+ 2 1/2). The findings of the individual panel members are then transferred into a single graph-like form, on a special chart. The procedure must be followed with precision, and with a little practice becomes an easy routine, quite rapidly This "Taste Pattern Chart", shown in FIGURE 4, has four vertical After being filled in, as illustrated in

executed.

columns, each for a different beer.

FIGURE 5, each column shows with perfect accuracy the reactions of all

participating panel members for the beer it represents, permitting to behold its evaluation by the entire taste panel at one glance. The taste categories appearing at left are a duplicate of those on the in dividual taste report forms described before. The top row of the chart consists of small squares, numbered from 1 to 10. These squares represent up to 10 panel members. Each panel member is assigned a permanent personal symbol, perhaps a cross, a triangle, a circle, and the like. In the small blank squares, just below the numbered squares, the corresponding personal symbols are inserted in whatever order the individual taste forms are perused. If inserted in color, perhaps red, the symbols stand out advantageously. The total number of participants (which of course can simply be counted) is conveniently indicated by the figure "10" or "8" etc. to the right of the squares. This done, the obligatory markings by each taster for the first four "basic" taste categories are indicated by inserting the "position" number of the dot he marked for each. If he marked the first dot it is indicated by the numeral 1, the second dot by the numeral 2, and so on, up to 5. For convenience and better clarity, circle markings ("average" conditions) are not considered and the squares left blank. Accordingly, in the category "STALE, OXID. **FRESH" the numeral 4 will never be inserted, since the circle occupies the fourth position. In the other three "basic" categories, the numeral 3 will not be inserted since the circle here occupies the third position. The large square areas to the right of each of these horizontal compilations serve to insert the arithmetical sum for each horizontal line, the sum being based

In our own practice, there is one exception to the rule of representing all cross markings by symbols on the Pattern Chart. For "HOP INTENSITY", markings of the second dot are not symbolized but ignored. Since every beer contains "hops", only markings for low (first dot) or strong (third and fourth dot) intensities are shown. A blank in this category simply indicates, by implication, an average hop intensity. At the bottom of the Pattern Chart the individual numerical ratings are inserted in their proper sequence, added up and divided by the number of participants so as to arrive at the average, or "Collective Panel Rating" for any given beer. Example: for Beer A in FIGURE 5 the individual ratings add up to +16 1/2;

16 1/2 divided by 10 (ten panelists) is +1. 7 (second decimals omitted, rounded off) which is the Collective Panel Rating, or C. P. R. for short, for Beer A. The

small figures at the bottom, such as 9/1/0 for Beer A signify that 9 tasters gave the beer a plus score, 1 taster a "0". and no taster a, minus score. The same procedure applies to all other beer samples. With this in mind, a brief interpretation of the four beers shown on the Pattern Chart in FIGURE 5 would be as follows. Generally, a conspicuous "bunching" of symbols is significant.

on a simple "plus-minus" scale where the circle position counts as 0 (zero). In relation to zero, each dot to the left of the circle has its corresponding "minus" value, and each dot to the right of the circle its corresponding "plus" value. For example, in the "BLAND HFLAVORFUL" category for Beer A shown

in FIGURE 5, four tasters each marked the first dot to the right of the circle (4 times +1 = +4) and one taster used the first dot to the left of the circle (-1), making an average of +3. Accordingly, the beer was rated above average in flavor fullness by the panel as a whole. For any of the other flavor categories, below the top four and below the space for "ODOR", wherever marked by a panelist, this panelist's personal symbol is inserted in the corresponding horizontal line of the Pattern Chart in such a manner that at the same time it also indicates the intensity (dot position) of his flavor marking. For example, if a panelist's symbol is a "v", and he marked on.his taste report form

coupled with properties registering very differently with different individuals. Generally, such an outcome calls for retasting the beer. In loose reference to the comments on Beer B in the foregoing example, the individual whose taste impressions were singled out as significant has a counterpart which I should not fail to mention in this context. It refers to the reticent or "timid" or stereotype panelist. This taster is extremely conservative in his markings. It is his nature to hold back, he is very reluctant to place emphasis on a taste sensation, and more often than not leaves a space unmarked or blank even though he certainly does receive some degree of flavor impact. His taste return frequently is a void. This individual, let us say, in one instance, applies to a, taste category which he normally does not mark at all, a low intensity mark. For any of the other panelists who are routinely more liberal in their ex-

pressions, a marking of this kind would be virtually meaningless. In his case, however, it assumes significance in view of his customarily reticent attitude. In the over-all evaluation of the beer in question, his voice should count, if not decisively, so certainly as weighty support for the impressions of the other panel members for this particular taste category, even if theirs have not been emphatic. Take the example shown in FIGURE 6. Three beers, X, Y, and Z, are judged by "Henry Jones" and "Robert Smith" in one and the same panel session. FIGURE 6 illustrates two individual taste record forms, one for Jones and one for Smith (in juxtaposition, separated by the black center line, for convenient comparison on a single page).

BEER A A highly acceptable product. Only tasters # 2 and # 4 (symbols <

and x) commented on a slightly cooked or bready oxidation flavor, not significant in the over-all picture. The C. P. R. of +1. 7 is generally a very favorable score. BEER B A fresh-tasting, fairly aromatic and estery product, flavorful, having a strong and evidently nice hop character. Only tasters #5 and #7 (symbols 0 However,

and o) suspected a faintly medicinal or phenolic background flavor.

if these two panelists possess acknowledged sensitivity in the detection of phenolic or similar flavors, their impressions, even though representing a small panel minority, may be significant irrespective of the otherwise excellent C. P. R of +2. 2 for the panel as a whole. These two tasters, of course, may be in error, but they also might not be. ER BE C Obviously very objectionable. Diacetyl strongly evident. Badly oxidized

(-12 in top row), fairly harsh (-5 in fourth row), inviting almost unanimous criticism and a C. P. R. of -2. 3 BEER D A controversial sample, causing perplexingly contradictory opinions, very favorable as well as very unfavorable, and resulting in a near-neutral C. P. R. of +0. 2. Evidently there is a strong accent on a malty-sweet- syrupy flavor,

Jones, the reticent and "stereotype" participant, is not given to many or to emphatic markings and customarily uses the mildest form of expression. He never marks the third or fourth dot, and rarely the second. Where Smith is

outspoken and generous in his markings, Jones may leave a blank, even though he may experience the same taste impression. Also the numerical ratings by Jones are conservative and close together, nearly always oscillating between a +2 and a -2, no matter how much he likes or dislikes a beer. In FIGURE 6, Beer Z as compared with Beers X and Y shall serve as a typical example. On the assumption that Jones and Smith are both equally qualified tasters, the habitual restraint of Jones forces u s to acknowledge that if Jones, in one instance, does express himself just slightly more vigorously than usual, where Smith makes bold markings all over the map (as for Beer Z in the example), Jones in his own reticent way lends support to the findings of Smith. In FIGURE 6, corresponding markings by Jones and Smith having significance in this context are shown encircled. The fact that Jones, against his usual habit, goes out of his way and marks, lo and behold, the second dot in the category "Aromatic, Winy", is noteworthy in the light of the much more emphatically expressed markings on the part of Smith for "Winy" and "Fruity". kind illustrated in FIGURE 6 are equally obvious. By the same token, the numerical rating applied by Jones to Beer Z is only very slightly below his other two ratings (+1 as against +1 1/2). Yet the very fact that Jones does apply to Beer Z a lower rating at all, again furnishes added validity to the much stronger misgivings expressed by Smith for the same beer. Jones's Other comparisons of similar

taste return alone would cut no ice. In company with Smith it does. Smith is flexible and, in a way, more "useful" to the reader and interpreter of his markings. His pendulum swings wide. But if the wide swing of his pendulum is

accompanied by only a tiny pendulum swing of his taste panel colleague Jones, Smith's findings acquire an extra measure of support. The coordinator who processes the individual taste returns must know his own taste panel members. If the Smiths are absent from the panel and only the Joneses are present (or vice versa), a correspondingly finer (or rougher) measuring stick must be applied in order to judge a beer as fairly as possible. Occasionally, a. panel participant may have to be disqualified, as in a case where his taste return is obviously out of tune with the rest of the panel and would thereby unduly affect the value of the final over-all panel scoring (always provided that the lone dissenter does not happen to be a taster whose singular faculty to detect special flavors hidden to the other panelists is activated in this instance and, so, carries acknowledged weight ... a contingency dwelt upon in Part I). If a panel member downgrades a beer sample with some radically expressed "minus" rating whereas all other tasters rate it favorably, or vice versa, then such a single gross dissent obviously calls for disqualification. However, certain situations raise the intriguing question as to how far a disqualification is merited, as in the demonstration that follows. For the sake of simplicity the example shown shall merely use the terms "good" and "poor" (the one signifying favorable "plus" ratings, and the other, low "minus" ratings).

Five beer samples numbered from 1 to 5 are judged in one and the same ing in the following evaluations: panel session by eight different tasters designated by the letters A to H, result-

Note that panelist C gives EACH beer, without exception, a POOR rating. Should he be disqualified, and if so, in which case? To arrive at an answer, let us examine two opposing views: (a) Selective disqualification, and (b) Total disqualification. (a)

appears only fair and is self-evident.

1, 2, and 3, where he is the lone dissenter and therefore most likely "wrong",

Selective Disqualification.

To disqualify panelist C for beers samples

With respect to sample 4, however, the negative judgment of taster C concurs with that of all other participants, so there would appear no reason whatsoever to disqualify him. It would seem fair and justified to let his rating count like the rest of the panel. Indeed if sample 4 had been the only beer to be judged by the panel, with no other beers alongside, the question of disqualification would not have arisen in the first place. Besides, and incidentally, beer sample 4 poses no evaluative problem anyway, since it is rated with such unanimity by the

whole panel (namely "poorly" in the example) that in the end result it makes no difference whether panelist C (or any other participant for that matter) is disqualified or not. Beer sample 5 presents a slightly different aspect, but does not alter the principle under consideration. Although taster C is not among the majority, he

certainly is not a lone dissenter but finds himself in the good company of tasters A and B (and, also, mildly supported by the "neutral" taste response of taster G). To disqualify taster C would mean discriminating against him since, after all, two of his fellow tasters, A and B, share his reaction. Consequently there is good

merit in letting the taste response of panelist C stand as recorded, without further questioning.

In short, the governing motive for disqualifying taster C in the case of samples 1, 2, and 3, but not for samples 4 and 5, in essence is no more than a kind of "arithmetical" device which selectively disregards his judgment only then when it happens to be patently out of line. (b) Total Disqualification. The logic of disqualifying taster C for sample

1, 2, and 3 takes into account the strong probability that his judgment was not up to par because he may have had a "bad day", or else his rating would not show up three times as a glaring deviation from all the others. If this premise is accepted, then, by the same reasoning, his "bad day" surely must apply to all beers he judges on that day, and not merely to some. Consequently his opinions and ratings should rightfully be stricken from the entire record,,including, beers 4 and 5,

regardless of whether in these two instances he just happens to be in agreement with some or all of the other tasters. These conflicting avenues of reasoning may seem like splitting hairs. But it is surprising how much in practical taste panel work a disparate judgment of one individual among a group of some seven or ten participants can affect the final and supposedly representative verdict of the panel as a whole (especially if expressed by some numerical rating system, and perhaps intended to be transmitted to an unsuspecting outside party). The dilemma that can arise on these occasions for the individual who processes the panel returns readily invites paraphrasing a well known quotation, "To disqualify or not to disqualify, that is the question" ... , a question which the patient reader perhaps also might be led to ponder now and then, if he is engaged in taste panel work. Good and meaningful exploitation of taste panel work frequently requires a certain dose of psychology blended with common sense. Negligence in this area

or the mere application of blind arithmetic in arriving at some "average opinion" expressed by some figure of a numerical system, involves pitfalls. A beer should not only be evaluated accurately and conscientiously, but also sensibly.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

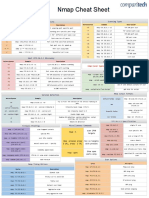

- Nmap Cheat SheetDokument1 SeiteNmap Cheat SheetAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 0 Introduction From Transcendental Magic Its DoctrineDokument23 SeitenChapter 0 Introduction From Transcendental Magic Its DoctrineAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ROUTER OSPF Configuration Some Explaination BY ALEX FOKDokument6 SeitenROUTER OSPF Configuration Some Explaination BY ALEX FOKAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Under The Big Top' Circus CostumesDokument1 SeiteUnder The Big Top' Circus CostumesAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bimbadeen Heights P.S. 5011: Year 6 Term 3 ActivitiesDokument3 SeitenBimbadeen Heights P.S. 5011: Year 6 Term 3 ActivitiesAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Description Part Numb Machine Note: Bad Solenoids 5771-4081 5631-5441 5541-4001 6391-4071 4021-4171Dokument3 SeitenDescription Part Numb Machine Note: Bad Solenoids 5771-4081 5631-5441 5541-4001 6391-4071 4021-4171Antonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bell Times For A 2.30pm FinishDokument1 SeiteBell Times For A 2.30pm FinishAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1870 Anonymous Text Book of FreemasonryDokument205 Seiten1870 Anonymous Text Book of FreemasonryAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combined PDFDokument51 SeitenCombined PDFAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1883 Anonymous Ritual and Illustrations of FreemasonryDokument286 Seiten1883 Anonymous Ritual and Illustrations of FreemasonryAntonio Imperi100% (7)

- Dev ListDokument6 SeitenDev ListAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAQs Freezium (English) - 01Dokument4 SeitenFAQs Freezium (English) - 01Antonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linking Words and PhrasesDokument4 SeitenLinking Words and PhrasesAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SQ L AlchemyDokument1.200 SeitenSQ L AlchemyAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydrostatic Testing ProcedureDokument2 SeitenHydrostatic Testing ProcedureAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SQ L AlchemyDokument1.200 SeitenSQ L AlchemyAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemistry of Beer AgingDokument25 SeitenChemistry of Beer AgingAntonio Imperi100% (1)

- 100 Mandalas BookDokument45 Seiten100 Mandalas BookAntonio Imperi86% (7)

- Sharp Hops AromaDokument31 SeitenSharp Hops AromaAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Date Day Sun in Details Other Aspects Moon Position: November 2013Dokument1 SeiteDate Day Sun in Details Other Aspects Moon Position: November 2013Antonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combrune - 1758 - An Essay On Brewing With A View of Establishing The Principles of The ArtDokument230 SeitenCombrune - 1758 - An Essay On Brewing With A View of Establishing The Principles of The ArtAntonio ImperiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Harry Seidler Revisiting Modernism PDFDokument24 SeitenHarry Seidler Revisiting Modernism PDFBen ShenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Marc Van de Mieroop's "The Ancient Mesopotamian City"Dokument6 SeitenReview of Marc Van de Mieroop's "The Ancient Mesopotamian City"ShamsiNinurtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communal HarmonyDokument27 SeitenCommunal HarmonyBhushan KadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decision Making ProcessDokument11 SeitenDecision Making ProcessLakshayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barabas in Patimile Lui IisusDokument26 SeitenBarabas in Patimile Lui IisusElena Catalina ChiperNoch keine Bewertungen

- TolemicaDokument101 SeitenTolemicaPrashanth KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire On Promotional TechniquesDokument2 SeitenQuestionnaire On Promotional TechniquesrkpreethiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Skenario 4 SGD 23 (English)Dokument16 SeitenSkenario 4 SGD 23 (English)cokdebagusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Converging Lenses Experiment ReportDokument4 SeitenConverging Lenses Experiment ReportCarli Peter George Green100% (1)

- Persuasive Unit Day 1-2 Johnston Middle School: 8 Grade Language ArtsDokument4 SeitenPersuasive Unit Day 1-2 Johnston Middle School: 8 Grade Language Artsbomboy7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conspiracy in New England Politics:The Bavarian Illuminati, The Congregational Church, and The Election of 1800 by Laura PoneDokument17 SeitenConspiracy in New England Politics:The Bavarian Illuminati, The Congregational Church, and The Election of 1800 by Laura PoneAndre MedigueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Babysitters: Vixens & Victims in Porn & HorrorDokument20 SeitenBabysitters: Vixens & Victims in Porn & HorrorNYU Press100% (3)

- Proclamation GiftsDokument17 SeitenProclamation Giftsapi-3735325Noch keine Bewertungen

- DevlinDokument127 SeitenDevlinbrysonruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Key Account ManagementDokument75 SeitenUnderstanding Key Account ManagementConnie Alexa D100% (1)

- Ivine Ance or Erichoresis: Tim Keller, Reason For God, 214-215. D. A. Carson, Exegetirical Fallacies, 28Dokument6 SeitenIvine Ance or Erichoresis: Tim Keller, Reason For God, 214-215. D. A. Carson, Exegetirical Fallacies, 28Bennet Arren LawrenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Do People Believe in Conspiracy Theories - Scientific AmericanDokument4 SeitenWhy Do People Believe in Conspiracy Theories - Scientific Americanapi-3285979620% (1)

- !beginner Basics - How To Read Violin Sheet MusicDokument5 Seiten!beginner Basics - How To Read Violin Sheet Musicrobertho10% (2)

- Microsoft Word - Arbitrary Reference Frame TheoryDokument8 SeitenMicrosoft Word - Arbitrary Reference Frame Theorysameerpatel157700% (1)

- Capital Investment Decisions: Cornerstones of Managerial Accounting, 4eDokument38 SeitenCapital Investment Decisions: Cornerstones of Managerial Accounting, 4eGeorgia HolstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Titus Andronicus and PTSDDokument12 SeitenTitus Andronicus and PTSDapi-375917497Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sahajo Bai AmritVaaniDokument4 SeitenSahajo Bai AmritVaanibaldevram.214Noch keine Bewertungen

- Figurative and Literal LanguageDokument42 SeitenFigurative and Literal LanguageSherry Love Boiser AlvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Graphing The Sine FunctionDokument4 SeitenGraphing The Sine Functionapi-466088903Noch keine Bewertungen

- Manthara and Surpanakha PDFDokument4 SeitenManthara and Surpanakha PDFKavya KrishnakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Media PsychologyDokument8 SeitenWhat Is Media PsychologyMuhammad Mohkam Ud DinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Truth MattersDokument537 SeitenTruth MattersAlexisTorres75% (4)

- Sciography 1Dokument4 SeitenSciography 1Subash Subash100% (1)

- Theory of RelativityDokument51 SeitenTheory of RelativityZiaTurk0% (1)

- How To Harness Youth Power To Rebuild India-Swami Vivekananda's ViewDokument6 SeitenHow To Harness Youth Power To Rebuild India-Swami Vivekananda's ViewSwami VedatitanandaNoch keine Bewertungen