Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Clanak 6

Hochgeladen von

Semir1989Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clanak 6

Hochgeladen von

Semir1989Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

(2012) 2:49-55 PROFESSIONAL PAPER

TREATMENT OF MORBID OBESITY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA - OUR EARLY EXPERIENCE

Samir ustovi, Haris Panda, Namik Hadiomerovi, Amina Krupalija, Ranko ovi, Nermin Mahmutovi, Davorka Matkovi, Senada Begi, Mohamad Khazmeh, Asim Alibegovi

ABSTRACT Background: Morbid obesity is becoming a very common problem in western countries. In Bosnia and Herzegovina there have been no publications connected to this issue. There are different surgical procedures in the treatment of morbid obesity. The most common and most efficient is LRYGB. Materials and methods: From October 2010 to June 2012 twenty-one patients with morbid obesity underwent surgery. Twenty patients were treated with LRYGB (laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) and one with LSG (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy). All patients were prepared for operation (preoperative diet, stopping smoking) in order to achieve a good preoperative condition. In this review we analyzed preoperative criteria, introducing standards for this procedure, intraoperative techniques and difficulties and postoperative outcome. Results: The median age of patients was 36.7, BMI 50.5, average operative time was 135.7 minutes, and average hospital stay was 3.14 days. We had one intraoperative complication: the nasogastric probe was stapled and reanasthomosis was performed. Average BMI loss after 6 months was 22.34% (for 11 patients) and after one year 31.59% (for 4 patients) compared to preoperative BMI and 15.17% compared to BMI measured six months after surgery. There were no major complications. Fourteen months after surgery postoperative incisional hernia occurred in one patient. Conclusions: LRYGB is a feasible and very effective method in the treatment of morbid obesity and its comorbidities. It has a considerably longer learning curve compared to cholecystectomy and a multidisciplinary approach is essential to achieve adequate results. As an alternative sleeve gastrectomy may be performed either as a definitive or temporary procedure.

Samir ustovi1 Haris Panda1 Namik Hadiomerovi1 Amina Krupalija1 Ranko ovi1 Nermin Mahmutovi1 Davorka Matkovi1 Senada Begi1 Mohamad Khazmeh1 Asim Alibegovi2

1

General Hospital Prim Dr

Abdulah Naka Sarajevo

INTRODUCTION Morbid obesity is becoming a very common problem in western countries. Approximately onethird of US adults are obese1. Current evidence suggests surgical therapies offer the best hope for substantial and sustainable weight loss. BMI > 40 (>35 and serious comorbidities) reduces excepted lifetime significantly, it is an independent risk factor for diabetes, impaired cardio-

Kranjevieva 12, 71000 Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina

2

Vaxjo Central Hospital, Vaxjo

Sweden E-mail: s_custovic@yahoo.com

49

vascular and respiratory function, physical ability, and fertility, and increases general cancer risk. Weight-loss surgery is the most effective treatment for morbid obesity, producing durable weight loss, improvement or remission of comorbid conditions, and longer life (weight loss in the extremely obese2, with resultant mortality reduction3). These truths, coupled with improved minimally invasive bariatric procedures, have driven a fourfold increase in the population-based rate of bariatric surgery over recent years4. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of a number of comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, degenerative joint disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, reflux esophagitis, stroke, coronary heart disease, venous stasis ulcers, cholelithiasis, erectile dysfunction and polycystic ovary syndrome. It is now generally accepted that bariatric surgery procedures induce long-term weight loss and offer resolution or dramatic improvement in numerous comorbidities of obesity, including type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia5. There are different surgical procedures in the treatment of morbid obesity. The original operation for morbid obesity, the jejunoileal bypass, was first performed in 1954. However, this purely malabsorptive operation led to unacceptable morbidity and mortality related to bacterial overgrowth and liver damage6. Restrictive operations decrease food intake and promote a feeling of fullness (satiety) after meals. Malabsorptive procedures, on the other hand, reduce the absorption of calories, proteins and other nutrients resulting in weight loss. The most common and most efficient is LRYGB, that combines both procedures7. Gastric bypass was introduced by Mason in 19668. The advantages of Roux-en-y gastric-bypass (RYGB) are: better weight loss than after purely restrictive procedures, low incidence of protein-calorie malnutrition and diarrhea as compared to purely malabsorptive procedures, and rapid improvement or resolution of weight-related comorbidities. The disadvantages of RYGBP are: technically more demanding, higher rate of complications compared to restrictive procedures, takes longer to perform7. According to some authors this type of operation is

also efficient in the treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Regression of diabetes mellitus type II (T2DM) was observed in 69.8% of patients while still hospitalized and an additional 19.1% of patients stabilized 12 weeks after surgery, which makes the total regression rate 88.9%. The remaining patients needed less medication for glycaemia control9. Restrictive gastric operations such as gastric banding can improve insulin resistance in proportion to weight loss, while gastrointestinal bypass procedures, such as RYGB and biliopancreatic diversion (BPD), can improve glucose homeostasis even before significant weight loss is reached, suggesting weight-independent mechanisms of action10. In fact, while RYGB does not affect insulin resistance but increases insulin secretion via the stimulation of nutrient-mediated incretin secretion, BPD induces full normalization of insulin resistance and, consequently, a significant reduction of insulin secretion. The insulin resistance reversion is only partially explained by the incretin level changes after BPD11. Among severely obese patients, compared with nonsurgical control patients, the use of RYGB surgery was associated with higher rates of diabetes remission and lower risk of cardiovascular and other health outcomes over 6 years12. The first problem is the fact that there is no financial support for these patients from health security institutions or government. The cost of the operation is too high for most candidates requiring a bariatric procedure. LRYGB is today the most widely spread operation in the treatment of morbid obesity. In B&H and this region until recently there were no reports of the successful introduction of this procedure. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety of introducing the procedure. Several months of theoretic consultation and lectures for all members of the interdisciplinary team should be undertaken before the first operation. Inspection of the diagnostic, surgical and other medical resources and facilities and cautious patient selections are mandatory before the first operation. The patients should have access to all relevant information and unlimited contact with surgeons. Preoperative patient education and preparation should be done to avoid any possible complications. A preoperative multidisciplinary checkup of

50

Figure 1. Access to peritoneal cavity through 10-mm Optiview trocar.

Figure 2. Creation of gastric pouch and gastrojejunal anastomosis.

the patients and proper documentation and checkup lists for all patients are made by the attending surgeon. MATERIAL AND METHODS From October 2010 to June 2012 twenty-one patients with morbid obesity underwent surgery. Twenty patients were treated with LRYGB (laparoscopic Rouxen-Y gastric bypass) and one with LSG (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy). All patients were prepared for operation (preoperative diet, stopping smoking) in order to achieve a good preoperative condition. In this review we analyzed the preoperative criteria, introducing standards for this procedure, intraoperative techniques and difficulties and postoperative outcome. Inclusion criteria: The patients with BMI greater than 40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI greater than 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities were included in the study. The operation was LRYGB for morbid obesity or LSG (laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy) in cases where the first operation could not be performed. A loss of 5% of initial weight was mandatory for all patients prior to surgery. All patients were operated by the surgical team, the operator and leader of the team was an external bariatric surgeon with significant experience who performs routine bariatric surgical procedures in his hospital in Sweden. The local team interviewed the patients and explained the

procedure and preoperative protocol. The surgeon who performed the operations with our team was familiar with all the information collected about the patients by electronic correspondence several weeks before the procedure. All patients received antibiotic and anticoagulant prophylaxis. Postoperatively, the patients were sent to the intensive care unit where vital signs, blood count and CRP were monitored until discharge from hospital. All patients were mobilized 2 hours after the end of the operation and took liquids. LAPAROSCOPIC ROUX-EN-Y GASTRIC BYPASS Preoperative intravenous antibiotics and DVT prophylaxis with unfractionated heparin and sequential compression devices were applied to all patients. Patients were placed in a supine position, legs apart in a steep reverse Trendelenburg. The surgeon stood between the legs. Local anesthesia was used before all skin incisions. An initial 10-mm Optiview trocar was placed in the midline, approximately 15 cm below the xiphoid process. Access to the peritoneal cavity was gained under direct vision (Figure 1). After creation of pneumoperitoneum, three 12 mm trocars were placed into the upper abdomen and one 5mm introduceer for introduction of a Nathanson liver retractor13. The upper stomach was exposed by retracting the liver

51

Figure 3. Creation of jejuno-jejunal anastomosis.

Figure 4. Transection of jejunum between two anastomoses.

with the Nathanson retractor. The angle of His was exposed by ultrasonic scalpel dissection. After opening the gastrohepatic ligament on minor curvature, the nasogastric tube was retracted to the esophagus and the first Endo GIA 60 mm stapler firing was done. Another Endo GIA 60 mm stapler was applied two to three times across the gastric cardia toward the angle of His in order to create a gastric pouch of 20 mm (Figure 2). A small gastrotomy of the pouch was done for future anastomosis. The patient was placed in a horizontal supine position to facilitate access to the jejunum for Roux-limb creation. The omentum was divided from its inferior side to the transverse colon. The first 50 cm of jejunum were measured using an intestinal grasper to determine the place of enterotomy and anastomosis (Figure 3). An Endo GIA 45 mm stapler with blue cartridge was inserted in the enterotomy that was created on the antimesenteric side. The stapler was then moved to the previously created gastrotomy on the pouch and gastrojejunal side to side anastomosis was created (Figure 4). The front side of the anastomosis was finished with an absorbable running suture (Vycril 2-0). Oversewing was done if necessary. The Roux limb measured 120 cm distally from the gastrojejunostomy and approximated to the bilopancre-

atic limb where jejuno-jejunal anastomosis was created using an Endo GIA and the antimesenteric borders of anastomosis were finished with Vycril 2-0 sutures. The jejunum was divided between these anastomoses with an Endo GIA white load stapler. Closure of the mesenteric defect and Petersens defects was performed to prevent internal hernia. An air bubble (Methylene blue) test was done to check for gastroenteric anastomosis. No drains and nasogastric tubes were left after the procedure. Trocars were removed to skin level and eventual bleeding sites were checked. The pneumoperitoneum was relieved, and all trocars were removed. Postoperatively, the patients were transferred to the intensive care unit. Sugar-free, clear liquids were started two hours after the end of the operation. The majority of patients were then discharged home that same day. SLEEVE GASTRECTOMY For sleeve gastrectomy the preoperative preparation and initial technique of trocar placement were identical as for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. In the beginning, the attachments at the Angle of His were divided by using a harmonic scalpel. Dissection of the greater curvature of the stomach was initiated 5cm proximally to the pylorus up to the Angle of His, with preservation of the gastroepiploic vessels. A 34-French (F) bougie

52

Figure 6. Morbidly obese patient with ventral hernia and Figure 5. Dissection of stomach in sleeve gastrectomy adhesions that required conversion from RYGB to sleeve gastrectomy.

was introduced to the esophagus along the lesser curvature and through the pylorus if feasible. The sleeve gastrectomy was created using a 60-mm Echelon (Ethicon Endosurgery) or Covidien Endo GIA multifire stapling device, beginning from a point 5cm proximally to the pylorus and reaching the Angle of His (Figure 5). The staple line was reinforced with running sutures. The resected stomach was extracted through the enlarged 15 mm trocar site, and the fascial defect was closed in order to prevent incisional hernia. Trocars were removed in same manner as in the previous technique. RESULTS The median age of the patients was 36.7, BMI 48.7 kg/ m2, average operative time was 135.7 minutes, and average hospital stay was 3.14 days. The average BMI was 40.2 kg/m2 after six months in 11 patients and 33.9 kg/ m2 after twelve months in 4 patients. We had one intraoperative complication: the nasogastric probe was stapled and reanastomosis was performed. Average BMI loss after 6 months was 22.34% (for 11 patients) and after one year 31.59% (for 4 patients) compared to preoperative BMI and 15.17% compared to BMI measured six months after surgery. There were no major complications. Fourteen months after surgery postoperative incisional hernia occurred in one patient.

DISCUSSION The concept of a learning curve for laparoscopic operations was introduced in the late 1980s. The concept arose after the identification of a higher rate of operative complications among surgeons who were still learning the laparoscopic technique. As new laparoscopic procedures have been developed over the last 1012 years, a significant learning curve for each procedure has been established. Schauers study indicates that LGB is associated with a significant learning curve that is perhaps more pronounced than many other advanced laparoscopic procedures. In this study, complications rates and operating times approached the levels reported for open gastric bypass after an experience of 100 cases14. LRYGB is feasible and very effective in the treatment of morbid obesity and its comorbidities. It has a considerably longer learning curve compared to cholecystectomy, and a multidisciplinary approach is essential to achieve adequate results. As an alternative sleeve gastrectomy may be performed as either a definitive or temporary procedure (Figure 6). Bariatric patients are connected with high operative risks8. The problem with the introduction of this procedure in hospitals is the lack of staff experience. The learning curve for this procedure is much longer than for other laparoscopic procedures. Introduction of bar-

53

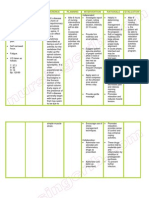

Table 1. BMI of 21 patients before and after surgery

REFERENCES 1. Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents and adults, 19992002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847-2850. 2. Fisher BL, Schauer P. Medical and surgical options in the treatment of severe obesity. Am J Surg. 2002;184(6B):9S-16S. 3. Sjstrm L, Narbro K, Sjstrm CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741-752. 4. Nguyen NT, Root J, Zainabadi K, Sabio A, Chalifoux S, Stevens CM et al. Accelerated growth of bariatric surgery with the introduction of minimally invasive surgery. Arch Surg. 2005;140:1198-1202. 5. Polymeris A. The pluses and minuses of bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: An endocrinological perspective. Hormones (Athens). 2012;11:223-240. 6. Buchwald H, Rucker RD. The rise and fall of jejunoileal bypass. In: Nelson RL, Nyhus LM (eds). Surgery of the small intestine. Appleton Century Crofts, Norwalk, CT. 1987. 529-541. 7. Lakdawala MA, Bhasker A, Mulchandani D, Goel S, Jain S. Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Rouxen-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1 year study. 2010;20:1-6. 8. Buchwald H. Consensus Conference Panel. Consensus conference statement bariatric surgery for morbid obesity: health implications for patients, health professionals and third-party payers. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:593-604. 9. Proczko-Markuszewska M, Stefaniak T, Kaska L, Kobiela J, Sledziski Z. Impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on regulation of diabetes type 2 in morbidly obese patients. Surgical Endoscopy. 2012;26:22022207. 10. Castagneto M, Mingrone G. The Effect of Gastrointestinal Surgery on Insulin Resistance and Insulin Secretion. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14:624-630. 11. Mingrone G. Role of the incretin system in the remission of type 2 diabetes following bariatric surgery. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:574-579.

Preoperative BMI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Average 44.6 47.55 45.68 60.6 66 49.22 43 42.27 66.46 58.4 40.1 45.4 48.4 42.7 42.7 41.8 43.5 52.5 50 51 41.6 48.7

BMI after 6 months 39.52 41.6 32.38 47.14 49.31 37.19 33.43 38.42 48 35.4

BMI after 12 months 31.38 32.8 30.6 40.8

40.2

33,9

iatric procedures is feasible but a serious learning approach and multidisciplinary team work is necessary. The specific protocols connected with the procedure should be strictly followed in order to avoid complications. A surgeon with a great deal of experience should be the leader of the team. According to our first experience after the 21 cases operated with LRYGB at our institution, bariatric surgery can be performed safely at the institutions without previous experience and expertise in this type of surgery. In our view the following were important: invited expertise; education of all members of the multidisciplinary team; rigorous control of the all phases of treatment and cautious patient selection and preoperative preparation.

54

12. Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, Kolotkin RL, LaMonte MJ, Pendleton RC, et al. Health benefits of gastric bypass surgery after 6 years. JAMA. 2012;308:1122-1131. 13. Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Hamad G, Eid GM, Mattar S, Cottam D, et al. Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Surgery: Current Technique. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques. 2003;13:229-239. 14. Schauer P, Ikramuddin S, Hamad G, Gourash W. The learning curve for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric. bypass is 100 cases. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:212215.

55

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Akutni Sindrom 1 PDFDokument59 SeitenAkutni Sindrom 1 PDFSemir1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dijagnoza 1 PDFDokument6 SeitenDijagnoza 1 PDFSemir1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Current Modalities in The Treatment of Non-Insulin Dependent DMDokument6 SeitenCurrent Modalities in The Treatment of Non-Insulin Dependent DMSemir1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fact Sheet - Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012 PDFDokument2 SeitenFact Sheet - Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012 PDFSemir1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pharmacy Code BookDokument162 SeitenPharmacy Code BookSemir1989Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Science: Modified Strategic Intervention MaterialsDokument28 SeitenScience: Modified Strategic Intervention Materialskotarobrother23Noch keine Bewertungen

- Endocrine Glands PDFDokument99 SeitenEndocrine Glands PDFXochitl ZambranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vertex Announces Positive Day 90 Data For The First Patient in The Phase 1 - 2 Clinical Trial Dosed With VX-880, A Novel Investigational Stem Cell-Derived Therapy For The Treatment of Type 1 DiabetesDokument3 SeitenVertex Announces Positive Day 90 Data For The First Patient in The Phase 1 - 2 Clinical Trial Dosed With VX-880, A Novel Investigational Stem Cell-Derived Therapy For The Treatment of Type 1 Diabetesዘረአዳም ዘመንቆረርNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salmon Dna: Introducing Scientific Breaktrough From JapanDokument6 SeitenSalmon Dna: Introducing Scientific Breaktrough From JapanLeonardo100% (1)

- Cacophony BurnTheGroundDokument32 SeitenCacophony BurnTheGroundLeo HurtadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leaflet Preeklamsia BeratDokument6 SeitenLeaflet Preeklamsia BeratSafitriNoch keine Bewertungen

- USMLE Step 1 First Aid 2021-101-230Dokument130 SeitenUSMLE Step 1 First Aid 2021-101-230mariana yllanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- USMLE 1 Hematology BookDokument368 SeitenUSMLE 1 Hematology BookPRINCENoch keine Bewertungen

- Gi SurgeryDokument51 SeitenGi SurgeryViky SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluating Diagnostics: A Guide For Diagnostic EvaluationsDokument5 SeitenEvaluating Diagnostics: A Guide For Diagnostic EvaluationsYanneLewerissaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 4 Environmental Pollution and Impacts On Public HealthDokument10 SeitenGroup 4 Environmental Pollution and Impacts On Public HealthBen KuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caffein Intox PDFDokument3 SeitenCaffein Intox PDFSejahtera SurbaktiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Class NotesDokument3 SeitenMental Health Class Notessuz100% (4)

- MMC 8Dokument27 SeitenMMC 8Neil Patrick AngelesNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Marcelino Campus San Marcelino, Zambales: Ramon Magsaysay Technological UniversityDokument33 SeitenSan Marcelino Campus San Marcelino, Zambales: Ramon Magsaysay Technological UniversityKristine Grace CachoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rizal in DapitanDokument2 SeitenRizal in DapitanMary Nicole PaedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yvonne Farrell Psycho Emotional NotesDokument10 SeitenYvonne Farrell Psycho Emotional Notesபாலஹரிப்ரீதா முத்து100% (2)

- WelcomeDokument74 SeitenWelcomeSagarRathodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zhou Et Al 2024 Mitigating Cross Species Viral Infections in Xenotransplantation Progress Strategies and ClinicalDokument9 SeitenZhou Et Al 2024 Mitigating Cross Species Viral Infections in Xenotransplantation Progress Strategies and ClinicalmnacagavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) : Case Investigation FormDokument2 SeitenCoronavirus Disease (COVID-19) : Case Investigation FormJudeLaxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Care Plan Pott's DiseaseDokument2 SeitenNursing Care Plan Pott's Diseasederic95% (21)

- 7 Chapter 7 T-Cell Maturation, Activation, and DifferentiationDokument34 Seiten7 Chapter 7 T-Cell Maturation, Activation, and DifferentiationMekuriya BeregaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burning Mouth Syndrome 1Dokument16 SeitenBurning Mouth Syndrome 1Mihika BalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- FNCP-Presence of Breeding or Resting Sites of Vectors of DiseasesDokument5 SeitenFNCP-Presence of Breeding or Resting Sites of Vectors of DiseasesAlessa Marie BadonNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDokument3 SeitenNew Microsoft Word Documentnew one10% (1)

- Bite Force and Occlusion-Merete Bakke 2006Dokument7 SeitenBite Force and Occlusion-Merete Bakke 2006Dan MPNoch keine Bewertungen

- Febrele HemoragiceDokument21 SeitenFebrele HemoragiceRotaru MihaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Process Fon Chap 1Dokument20 SeitenNursing Process Fon Chap 1Saqlain M.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Multiple Pulp Polyps Associated With Deciduous TeethDokument4 SeitenMultiple Pulp Polyps Associated With Deciduous TeethJea Ayu YogatamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHN Practice Exam 1Dokument7 SeitenCHN Practice Exam 1Domeyeg, Clyde Mae W.100% (1)