Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Fundamentals of Academic and Professional Writing

Hochgeladen von

fiahstoneOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Fundamentals of Academic and Professional Writing

Hochgeladen von

fiahstoneCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Introduction to the Course

--Valerie Ross

Focusing on the fundamentals of academic and professional writing, our seminars will sharpen your reasoning and research skills, and teach you how to write with logical precision. Expect an intensive, demanding experience that requires your full participation. Be prepared for a different tempo: the workload is steady rather than coming in mid-term and final spikes. If you keep up, your mid-term and final portfolio essays will be well underway by the time the deadline for them nears. Along with having a steady tempo, this course is structured incrementally. One lesson builds on the next. If you dont grasp the lesson in the first draft, you will have a chance to demonstrate your comprehension and ability to implement it in the next sequence. Critical writing resembles mathematics. It is grounded in logic and problem-solving, and to advance one has to be able to identify and define the problem and have at the ready not only an intellectual understanding of certain concepts, but also an ability to implement them in a variety of situations. The task in this class is to grasp some basic concepts of reasoning and be able to implement these in response to issues and debates that you identify through your ongoing immersion in the seminar topic. You will find that, like learning a new concept in math, you are unlikely to get it right the first time. It takes practice, trial and error. If you dont learn it, you wont be able to move on to the next level. Thus its important to keep up. The work is steady and manageable if you allot sufficient time for it. Among other things this course will teach you is how to organize your time to meet a steady stream of deadlines. We strongly encourage you to set up a calendar, online or paper, whatever youre likeliest to put to use. Insert all of your assignments for this course and the others you are taking. Set aside six hours a week for each course. You will likely use all six for your writing seminar. If you discover that you do not need six in a particular week, you will undoubtedly have things to do with free time. In terms of grades, you are given an opportunity to demonstrate your mastery of various concepts as a particular sequence unfolds. If you do not do well on an assignment in the Justificatory Reasoning sequence, you will have opportunities to revise it, as long as you submitted your drafts on time. For example, if you do not get the hang of Justificatory Two Reasons, but you have your aha moment as youre writing your next assignment, Counterargument, Refutation, Concession, your grade for the first assignment will be adjusted. Grades and feedback on assignments are designed to encourage independent thinking and problem-solving rather than fixing your paper. Feedback will let you know which concepts you have successfully mastered (you can recognize and evaluate them) and implemented (your own writing demonstrates it). This in turn allows you to identify concretely what you need to work on for the next assignment, as well as to build your knowledge and repertoire of writing strategies so that, by the end of class, you will be an independent writer. Thus expect your Critical Writing feedback to differ from the conventions of writing feedback youve likely received in the past. It will be brief, concrete, and quantitative so that you can focus on the structural integrity, the logical and semantic coherence of your writing. In the first half of the course, a series of short formal exercises will give you practice in generating and supporting your own ideas rather than responding to topics and prompts generated by your teachers. Introducing you to the basics of scholarly and professional discourse, the seminar will also emphasize writing to real audiences: your colleagues in the class, your instructor, and your outside readers. Writing to real audiences compels writers to become more strategic, to make decisions and revisions not only on the basis of a topic and purpose, but also on what your readers are likely to find compelling. Persuading an academic audience requires you to become fluent in the rhetoric and arrangement of reasoning. The written expression of informal logic will replaceor more accurately, advancethe thesis-and-topic-sentence mode you likely practiced in high school, where your project was to support a thesis with examples and insure that each paragraph had a topic sentence related to the thesis. In most cases, students in this seminar will be moving away from the more associative, poetic, free-flowing structure of creative nonfiction and literature and toward the formal validity used in mathematical and logical proofs. Scholarly and professional writing is the main way that knowledge is produced and legitimated. Scholarly writers must put an idea through its paces for others to publish and accept the findings. Scholars and professionals,

particularly in the social and natural sciences, business, and engineering, strive for the demonstration of formal validity, logical precision, in their writing. This process of logical validation, adapted to the wiles of language, is used to create, test, and confirm knowledge as well as serve as the basis for much decisionmaking. Thus while a lay reader may be persuaded by a lovely turn of phrase or gorgeous metaphor when reading a piece of creative writing, scholars and professionals are more readily persuaded by solid reasoning concisely expressed. This does not mean that you will abandon or find useless what you have already learned as a writer. Indeed, our method depends on the fact that you have already learned how to write good sentences and know how to cohere these into paragraphs that support a thesis. We expect you to build upon that knowledge. For example, you will learn to support your thesis with strategies that are more pointed and purposeful than a topic sentence. You will learn that a thesis is one term and approach to organizing ones reasoning among many others used by disciplines and professions, and which we gather under the broader term, propositions. Depending on the disciplines particular approach and purpose, it may seek instead of a thesis perhaps a hypothesis, argument, claim, objective, proposal, proposition, statement of purpose or project. You will become adept at the mental abstraction and generalizing processes that produce reasons, which will replace the topic sentences youre currently accustomed to writing. You will learn strategies for organizing your essays that are based upon the dynamics of argumentation and the disposition of your intended readership. You will continue to use your understanding of two major rhetorical forms, the introduction and the conclusion, and will add to these a knowledge of other rhetorical forms used in the rhetoric of reasoning, such as refutation and concession. As you become fluent in the rhetoric of reasoning, you will become capable of producing as well as recognizing strong reasoning when you encounter it. You will also be equipped to identify weak reasoning, logical incoherence, and rhetorical trickery and deception. In order for this knowledge to become secondnature, you will be getting intensive practice in rhetorical analysis by paraphrasing as well as analyzing and identifying the reasoning strategies you and others use (or fail to use) in each sentence. While painstaking, this method of close reading and analysisor more accurately, this awareness of ones logical frameworkis a staple of most scholarly work. The rhetorical outlines will accelerate your fluency in reasoning and allow you to identify and evaluate the reasoning of a colleague or a scholar: whether its a assigned text in another class or a politicians speech, you will readily identify what the rhetor wants you to believe, and how he or she is attempting to persuade you to do so. An evaluation of anothers reasoning strategiesthe means by which they arrived at their conclusionis how scholars determine the validity of others propositions, as well as justify and legitimate their own. The outlines and close reading teach you to be conscious not only of what you are saying, but also of whether your reasoning is sound. In the second half of the seminar, you will turn from argumentation (justificatory reasoning) to explanation, building upon what you have learned as well as considerably expanding your critical writing repertoire and sophistication. Among other things, you will commence the adventure of joining a scholarly debate or discussion specifically related to your course topic. All of the readings, the exercises, the outlines incrementally immerse you in an understanding of the topic as well as in how to communicate, as writers, in that field. You will advance your knowledge of research techniques and resources, and acquire additional strategies for gathering, analyzing, synthesizing, creating and evaluating knowledge and arguments as you are introduced to advanced methods of analysis and creative thinking. This work will prepare you for the final essay you will write in the course, as well as for research-based writing at the college level and beyond. Upon satisfactory completion of the course, you should be able to look at any scholarly book or article, identify its reasoning strategies, issues, forms of evidence, and major players. If you examine two or three of the same genre, same field, same topic, you will be able to identify the features of the genre, major players, and the general contour of the conversation these scholars are having about the topic. You will know what kind of work you will need to do to enter their conversation and participate in their conversation and genre of writing. You will be an independent, or rather, interdependent writer, one who is capable of reading, analyzing, writing, and evaluating reasoned discourse, addressed to real audiences who want to know what you have to say; and you will know whether you have something worth saying. You will also be introduced in two stages to a highly structured, purposeful form of peer review, one that is

professionally oriented and audience-, rather than teacher-based. That means that your job isnt to correct your peers worki.e., clean up sentencesbut rather to see that your partners reasoning is sound, its expression clear and logical, its proposition, reasons, and evidence sufficiently persuasive and inventive. This is not a creative writing course, and thus your focus in the semester will not be on writing ever more beautiful sentences. The highest value in critical writing is the idea, the reasoning, the evidence. Beautiful expression is always a plus, but its frosting rather than the cake for most disciplines. Some frown upon beautiful writing, preferring plain, sober, precise, economical prose that doesnt intrude upon the meaning or clarity of the proposition and reasoning. While we cant prepare you for each stylistic encounter you will have at Penn and beyond, we will equip you with strategies for analyzing a discipline to determine whether it relishes or scorns literary language, and whether, for example, it prefers text-based or data-based evidence. While a few disciplines or subdisciplines, as for example in literary studies, may be be more individualist and even experimental in form, you will find that most, including many subdisciplines in literary studies, regard logical structure as the baseline for credibility in their fields. Our course will prepare you for both ends of the continuum. Research suggests that, in general, the cognitively uninhibitedthe open-mindedlearn more, and more quickly, than the inhibited, resistant person. While you are likely at various points to find our approach frustrating and tedious, just as one finds practicing the scales in music or doing drills in sports, know that every aspect of this seminar is designed to immerse you quickly and efficiently in the art of critical thinking and writing. You can reinforce these lessons by applying what you are learning in your writing seminar to what you are reading in other classes: identify the propositions, reasons, evidence, assumptions, the arrangement of materials. Listen to political debates and everyday conversations and practice identifying their explanations, reasons, evidence; identify logical fallacies. Notice how writing assignments in other courses ask you to perform one or more of the exercises, types and strategies of reasoning, operations of knowledge and research, that you are learning in the seminar. The more you practice these things, the more value you will extract from the experience; the sharper your skills of reasoning and persuasion; and the greater your control over your writing. In fact, the effort you put into this work will result in your being able to help others with their writingadvising them how to organize and develop their propositions rather than being forever the dependent writer, waiting for someone to tell you that your writing is good or to tell you how to fix it. While artists and artisans typically seek feedback, they dont need anyone to tell them how to fix their work. They want to know if it appeals to their audience, if the art hit its mark. Our aim is to move you from Platos category of someone who has a bit of a knack for writingwho now and again manages to pull off a good paper, for reasons mysteriousto an artist versed in the craft.

Why These Short Exercises?

Every culture has a proverb or a joke about breaking big jobs into smaller manageable pieces (How do you eat an elephant? A bite at a time.) My favorite is the African proverb, A little rain each day will fill the rivers to overflowing. As the semester progresses, you will discover that you often have more to say than can fit into those 500 word increments. This is a good thing. It compels you to edit, rather than pack your writing with styrofoam peanuts, those sentences and words that do little more than fill space. By learning how to write a short, concise, naked propositionone that leaves no doubt about what you are going to explain or proveyou will discover how much you have to write about a topic. As one of my mentors advised, the smaller the question, the bigger the answer, a lesson she learned while writing her dissertation. As the demands upon the writer increase, so too the need to set aside the bad habit of binge-writing and learn how to write in chunksthought units that you later cohere and edit, or sometimes find of no use. The linear approach to writing that one sometimes learns in high school and the early years of college is insufficient to address the increasingly complex kinds of writing asked of us as we advance in our college and professional lives. Thus one of our goals is to change your habits of writing so that you plan ahead for papers and learn to research and write in chunks. You begin with a tentative proposition based on whatever knowledge you have already gleaned, and then evolve and refine it as your studies, discussion, and feedback accumulate. You write as you learn and as ideas incubate. Your knowledge grows and your thinking evolves. Indeed, over the course of a few weeks or months you may revise a proposition many

times. Developing an inventive, solid proposition doesnt happen overnight. Waiting until the last week to do your research and writing guarantees second-rate thinking. Learning how to write in chunks in a leisurely, disciplined fashion allows you to capture your research and your ideas as you go along, allowing you to follow hunches and make connections, work that your brain does while you are busy doing something else. This process also allows you to develop a carefully reasoned and well-supported essay that you have built thoughtfully, piece by piece, in a reflective, recursive process. Binge-writing a bookthe longest of all writing assignmentsis of course physically impossible, just as binge-writing articles, chapters, and long papers in the bleary-eyed wee hours of the night is foolhardy and ineffective. Thus nearly all scholars and professional writers, as well as novelists and screenwriters, learn to write in chunks, for good reason: Our brains generally cant handle more than 5 bits of information or 90 minutes of mental work. Thereafter, like any other overworked muscle, the brain forgets, loses connections, makes poor decisions. A 500 word chunk will usually take fewer than 90 minutes to draft and contain no more than 5 significant pieces of information. Writing in chunks teaches you how to write as you research, an interdependent process that helps you stay on track, testing your short pieces against your proposition, recording sources, quotations, ideas, and connections as you have them, rather than attempting to recall and reconstruct them under the pressure of a deadline. Chunk writing reinforces and nourishes working memory, which facilitates concept-formation. Writing reasoned units of thought, as you have been taught, disciplines, clarifies, tests, and organizes your thinking to meet the rhetorical as well as intellectual demands of your readers. It exposes gaps and contradictions in your reasoning or evidence that you will have time to address as your project unfolds, rather than being ambushed by them under deadline pressure. Writing in chunks as you research means that your paper is all but done by the time you finish your research. Your main joba challenge of sorts, but nothing like writing a paper at the last minuteis to cohere the chunks, write your introduction and conclusion, refine your proposition, polish. Writing in chunks is not only a superb approach to incubating and organizing strong ideas, but is also a superb time management strategy (see tips below)

This is why skillful writers think, and write, in these units of thought. This is probably a good time to underscore, once again, that we do not expect that you will write in the strict formats of the three-paragraph exercises, though they will serve you well if you choose to use them. The exercises are meant to immerse you in the basics of reasoning, as well as teach you how to write solid, coherent, unified, well-developed paragraphs that link to each other and to the propositionfundamental to good critical writing While most professionals write in chunksa couple of paragraphs or sometimes a few pagesthey have different ways of storing and working with them. Some create paper or online folders organized by subpropositions or themes related to their propositions. Others maintain a continuous scroll, rereading what came before (or in Joan Didions case, retyping every line of what came before!) to which they then add or insert their next chunk of writing. A former colleague of mine, a prolific writer, prints out each chunk and tapes it to his dining room wall, where he rearranges and inserts new pieces as he goes along. To make this approach to writing a seamless part of your academic life, here are a few tips: Make sure each chunk you write has a subproposition in other words, a purpose related to your proposition-in-progress. Continue to revise your propositionand sometimes your subpropositions--as you go along Time yourself: how long does it take you to write 500 words? By semesters end, it should take you no more than 90 minutes to write an acceptable, reasoned 500 word working draft. Set goals: I will write 250 or 500 words a day.

Start writing before youre ready and stop when youve reached 500 words or when the timer goes off. That will keep you on track, it will insure that youll have more to write the next day, and you will be managing your writing process like a pro.

Using this plan allows your ideas to incubate and your brain to start fresh and nourished each day. It also alerts you to the need for additional research, which you can do as you go along, rather than find yourself spinning your wheels, exhausted, at the eleventh hour.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Writer's Choice Grade 9 Student Edition Grammar and CompositionDokument987 SeitenWriter's Choice Grade 9 Student Edition Grammar and CompositionChristopher Lott89% (9)

- UntitledDokument2.657 SeitenUntitledNindya Isnanda100% (3)

- 161 Basic ConceptsDokument3 Seiten161 Basic Conceptsilham ilahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Core Textbook) Teaching ESL Composition-Purpose, Process, PracticeDokument446 Seiten(Core Textbook) Teaching ESL Composition-Purpose, Process, PracticeDanh Vu100% (2)

- SSES-Letter-of-Intent-jen (AutoRecovered) (AutoRecovered)Dokument16 SeitenSSES-Letter-of-Intent-jen (AutoRecovered) (AutoRecovered)ADELO CANON100% (1)

- School Form 10 SF10 Learner Permanent Academic Record JHS Data Elements DescriptionDokument3 SeitenSchool Form 10 SF10 Learner Permanent Academic Record JHS Data Elements DescriptionJun Rey LincunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orca Share Media1699427701894 7127916407768776920Dokument33 SeitenOrca Share Media1699427701894 7127916407768776920julieannlipata8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Solution Focused Brief CounselingDokument8 SeitenSolution Focused Brief Counselingpreciousrain07Noch keine Bewertungen

- Management ControlDokument304 SeitenManagement ControlBENCHALGONoch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Writing GuideDokument20 SeitenAcademic Writing GuideDherick RaleighNoch keine Bewertungen

- Turning to Research WritingDokument3 SeitenTurning to Research WritingfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Writing Project OverviewDokument14 SeitenResearch Writing Project OverviewfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Do You Write The Discussion Section of A Research PaperDokument5 SeitenHow Do You Write The Discussion Section of A Research Paperfyrgevs3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Is Thesis The Same As Main IdeaDokument4 SeitenIs Thesis The Same As Main IdeaHelpMeWriteMyEssayCambridge100% (2)

- Thesis Driven Essay TemplateDokument6 SeitenThesis Driven Essay Templatetiffanysandovalfairfield100% (2)

- How To Write A Thesis About A BookDokument4 SeitenHow To Write A Thesis About A Booksandysimonsenbillings100% (2)

- Philosophy Research Paper GuidelinesDokument8 SeitenPhilosophy Research Paper Guidelinesfvg7vpte100% (1)

- Define Thesis in LiteratureDokument4 SeitenDefine Thesis in Literatureafcnahwvk100% (2)

- How To Make Perfect Thesis StatementDokument6 SeitenHow To Make Perfect Thesis Statementdonnabutlersavannah100% (2)

- Thesis and Claim DifferenceDokument4 SeitenThesis and Claim Differencesarahmitchelllittlerock100% (2)

- Where Should Your Thesis Statement Be Located in Your PaperDokument6 SeitenWhere Should Your Thesis Statement Be Located in Your Paperbkrj0a1kNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example of Rhetorical Analysis Thesis StatementDokument5 SeitenExample of Rhetorical Analysis Thesis Statementdwndnjfe100% (2)

- Tentative Thesis For Research PaperDokument7 SeitenTentative Thesis For Research Paperxcjfderif100% (1)

- In A Research Paper A Thesis Statement ShouldDokument5 SeitenIn A Research Paper A Thesis Statement Shouldgz9avm26100% (1)

- What Do You Write A Thesis ForDokument4 SeitenWhat Do You Write A Thesis Formeganfosteromaha100% (2)

- Dissertation Structure Chapter 1Dokument7 SeitenDissertation Structure Chapter 1AcademicPaperWritersTucson100% (1)

- Steps Involved in Thesis WritingDokument7 SeitenSteps Involved in Thesis WritingNeedSomeoneWriteMyPaperUK100% (2)

- Term Paper Thesis StatementDokument7 SeitenTerm Paper Thesis StatementSarah Brown100% (2)

- Thesis For Literary AnalysisDokument7 SeitenThesis For Literary Analysislaurabenitezhialeah100% (2)

- Academic Writing StructureDokument9 SeitenAcademic Writing StructureIerdna RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writer Thesis DefinitionDokument4 SeitenWriter Thesis DefinitionPayToDoMyPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Literary Research Paper Thesis StatementsDokument4 SeitenLiterary Research Paper Thesis Statementsrebeccaharriscary100% (2)

- Another Name ThesisDokument6 SeitenAnother Name Thesisbsr6hbaf100% (2)

- What If ThesisDokument4 SeitenWhat If Thesisaswddmiig100% (2)

- Thesis Key TermsDokument6 SeitenThesis Key Termsalissacruzomaha100% (2)

- Course Thesis WritingDokument6 SeitenCourse Thesis WritingPayForSomeoneToWriteYourPaperBillings100% (2)

- Where Does The Thesis Statement Go in An EssayDokument5 SeitenWhere Does The Thesis Statement Go in An EssayPaperWritingCompanyCanada100% (2)

- Writing The Thesis Statement For Research PaperDokument4 SeitenWriting The Thesis Statement For Research Paperaflbmmddd100% (1)

- Thesis Statement Worksheet For Middle SchoolDokument5 SeitenThesis Statement Worksheet For Middle Schooldanaybaronpembrokepines100% (2)

- Design Dissertation StructureDokument4 SeitenDesign Dissertation StructurePayToDoMyPaperDurham100% (1)

- Topic Sentence Thesis OutlineDokument8 SeitenTopic Sentence Thesis Outlinerebeccarogersbaltimore100% (2)

- Can You Use We in Research PaperDokument6 SeitenCan You Use We in Research Papercafygq1m100% (1)

- An Example of A Research Paper Thesis StatementDokument4 SeitenAn Example of A Research Paper Thesis Statementbkxgnsw4100% (2)

- How To Write A Thesis Statement in An EssayDokument4 SeitenHow To Write A Thesis Statement in An Essaydwns3cx2100% (2)

- Examples of Thesis Statements For College EssaysDokument7 SeitenExamples of Thesis Statements For College Essaysmelissalusternorman100% (2)

- How To Write A Good Rhetorical Analysis ThesisDokument7 SeitenHow To Write A Good Rhetorical Analysis Thesislissettehartmanportsaintlucie100% (2)

- How To Start Off A ThesisDokument7 SeitenHow To Start Off A ThesisDereck Downing100% (2)

- Thesis Rhetorical DefinitionDokument4 SeitenThesis Rhetorical Definitionaliciajohnsondesmoines100% (2)

- How Do You Make A Thesis Statement For A Research PaperDokument7 SeitenHow Do You Make A Thesis Statement For A Research Papergw2cy6nxNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Make A Good Introduction For A ThesisDokument5 SeitenHow To Make A Good Introduction For A Thesispenebef0kyh3100% (2)

- A Short Guide To Writing A ThesisDokument5 SeitenA Short Guide To Writing A ThesisAmy Isleb100% (1)

- Writing Thesis Is HardDokument6 SeitenWriting Thesis Is Harderintorresscottsdale100% (2)

- Junior High Research Paper ExamplesDokument4 SeitenJunior High Research Paper Examplesfvesdf9j100% (1)

- Where Should Your Thesis Statement Be in An EssayDokument5 SeitenWhere Should Your Thesis Statement Be in An Essaystephaniewilliamscolumbia100% (1)

- Thesis Directional StatementDokument8 SeitenThesis Directional Statementmandycrosspeoria100% (2)

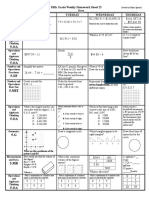

- 5 Guide To Writing Rhetorical OutlinesDokument6 Seiten5 Guide To Writing Rhetorical OutlinesfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A Thesis For An Evaluation EssayDokument7 SeitenHow To Write A Thesis For An Evaluation Essaylhydupvcf100% (2)

- Basic Thesis StructureDokument5 SeitenBasic Thesis Structurecgvmxrief100% (2)

- How To Format A Thesis Statement For A Research PaperDokument8 SeitenHow To Format A Thesis Statement For A Research PaperafmcofxybNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Essays or Expository Writing vs. Research Papers What Is The DifferenceDokument7 SeitenPersonal Essays or Expository Writing vs. Research Papers What Is The DifferenceaflbtcxfcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differentiate Theme From Thesis StatementDokument5 SeitenDifferentiate Theme From Thesis StatementCheapPaperWritingServiceUK100% (2)

- Where Should The Thesis Be in A Research PaperDokument4 SeitenWhere Should The Thesis Be in A Research Paperlelajumpcont1986100% (2)

- Perfect Thesis Statement ExamplesDokument4 SeitenPerfect Thesis Statement Examplesjennycalhoontopeka100% (1)

- Parts of A Academic Research PaperDokument8 SeitenParts of A Academic Research Paperh01fhqsh100% (1)

- What Must A Thesis Statement IncludeDokument5 SeitenWhat Must A Thesis Statement IncludeBrittany Brown100% (2)

- Example Thesis Statements For Research PapersDokument7 SeitenExample Thesis Statements For Research Papersqfsimwvff100% (2)

- Thesis Statement For A Critical AnalysisDokument6 SeitenThesis Statement For A Critical Analysislcdmrkygg100% (2)

- Author Source Synthesis OutlineDokument5 SeitenAuthor Source Synthesis OutlinefiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment: The Research EssayDokument1 SeiteAssignment: The Research EssayfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 32 Coming To Terms - PlagiarismDokument4 Seiten32 Coming To Terms - PlagiarismfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 27 Explanation Versus Justification in The Discipline of EnglishDokument2 Seiten27 Explanation Versus Justification in The Discipline of EnglishfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 22 The Cover LetterDokument6 Seiten22 The Cover LetterfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis: Author and Sources Assignment SequenceDokument1 SeiteSynthesis: Author and Sources Assignment SequencefiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- V Ross Explanatory ReasoningDokument4 SeitenV Ross Explanatory Reasoningfiahstone321Noch keine Bewertungen

- 18 EndingsDokument5 Seiten18 EndingsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28 Known-Item SearchingDokument2 Seiten28 Known-Item SearchingfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 23 Midterm Position Paper InstructionsDokument1 Seite23 Midterm Position Paper InstructionsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise 4. Arrangement: The Nestorian Order: InstructionsDokument4 SeitenExercise 4. Arrangement: The Nestorian Order: Instructionsfiahstone0% (1)

- 17 Refutation Concession InstructionsDokument4 Seiten17 Refutation Concession InstructionsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18 EndingsDokument5 Seiten18 EndingsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Peer Review ProcedureDokument2 Seiten15 Peer Review ProcedurefiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 PropositionsDokument3 Seiten6 PropositionsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19 ArrangementDokument5 Seiten19 ArrangementfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 IntroductionsDokument7 Seiten12 IntroductionsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 Justificatory Reasoning - Two Reasons Excercise & OutlineDokument5 Seiten14 Justificatory Reasoning - Two Reasons Excercise & OutlinefiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16 Refutation and ConcessionDokument2 Seiten16 Refutation and ConcessionfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Analysis and SynthesisDokument7 Seiten8 Analysis and SynthesisfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 PremisesDokument4 Seiten7 PremisesfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 Justificatory Outline InstructionsDokument4 Seiten13 Justificatory Outline InstructionsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 Three Justificatory PropositionsDokument1 Seite11 Three Justificatory Propositionsfiahstone0% (1)

- 10 Reasons Versus EvidenceDokument2 Seiten10 Reasons Versus EvidencefiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Justificatory ReasoningDokument3 Seiten9 Justificatory ReasoningfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Guide To Writing Rhetorical OutlinesDokument6 Seiten5 Guide To Writing Rhetorical OutlinesfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reasoning: Narrative Reasoning: Organizes Raw Data Into A Story Form. The Proposition in Narrative Reasoning IsDokument4 SeitenReasoning: Narrative Reasoning: Organizes Raw Data Into A Story Form. The Proposition in Narrative Reasoning IsfiahstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

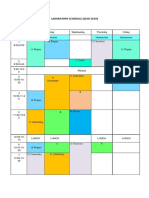

- Laboratory ScheduleDokument3 SeitenLaboratory ScheduleAyu ChristiNoch keine Bewertungen

- School Days Reminiscing CardsDokument9 SeitenSchool Days Reminiscing CardsAnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Jaime Alvarado (Jaime Alvarado)Dokument3 SeitenCurriculum Jaime Alvarado (Jaime Alvarado)yuly aldanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fs 41Dokument38 SeitenFs 41analynNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Mere Word . .To A Global BrandDokument28 SeitenA Mere Word . .To A Global Brandjitinm007100% (1)

- 23-24 School CalendarDokument1 Seite23-24 School Calendarapi-301587209Noch keine Bewertungen

- Veyldframework (1) 2 PDFDokument44 SeitenVeyldframework (1) 2 PDFPauNoch keine Bewertungen

- MINOO - Final ThesisDokument267 SeitenMINOO - Final ThesisDarell SuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue Hat Green Hat by Sandra BoyntonDokument10 SeitenBlue Hat Green Hat by Sandra Boyntontanvi100% (11)

- Esl ProjectDokument24 SeitenEsl Projectapi-252428751100% (1)

- Certfication TambanDokument3 SeitenCertfication TambanPequiro Nioda RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- K Tressler ResumeDokument4 SeitenK Tressler Resumeapi-423519868Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2014 15 GraduateDokument306 Seiten2014 15 GraduateyukmNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHS Work Immersion ExperienceDokument72 SeitenSHS Work Immersion ExperienceCARL JACOB MERCADONoch keine Bewertungen

- ResumeDokument2 SeitenResumeMA. LOWELLA BACOLANDONoch keine Bewertungen

- Gonzales Cannon November 21 IssueDokument34 SeitenGonzales Cannon November 21 IssueGonzales CannonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alex Casili Photobook PDFDokument3 SeitenAlex Casili Photobook PDFHanuren TNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 6 17weekly Homework Sheet Week 23 - 5th Grade - CcssDokument3 Seiten3 6 17weekly Homework Sheet Week 23 - 5th Grade - Ccssapi-328344919Noch keine Bewertungen

- Report On Learner'S Observed Values 1 2 3 4Dokument2 SeitenReport On Learner'S Observed Values 1 2 3 4jussan roaringNoch keine Bewertungen

- NAMA KELOMPOKDokument4 SeitenNAMA KELOMPOKTiara araNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Daily Tar Heel For July 21, 2016Dokument6 SeitenThe Daily Tar Heel For July 21, 2016The Daily Tar HeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- ARF Nursing School 05Dokument7 SeitenARF Nursing School 05Fakhar Batool0% (1)