Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Fredman, Christie y Bear, 2007

Hochgeladen von

Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Fredman, Christie y Bear, 2007

Hochgeladen von

Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry http://ccp.sagepub.

com/

Reflecting Teams with Children: The Bear Necessities

Glenda Fredman, Deborah Christie and Ndibeer Bear Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007 12: 211 DOI: 10.1177/1359104507075922 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ccp.sagepub.com/content/12/2/211

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ccp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ccp.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://ccp.sagepub.com/content/12/2/211.refs.html

>> Version of Record - May 1, 2007 What is This?

Downloaded from ccp.sagepub.com at FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y LETRA on October 15, 2013

SPECIAL SECTION Reecting Teams with Children: The Bear Necessities

GLENDA FREDMAN

Camden and Islington Mental Health and Social Care Trust, London, UK

DEBORAH CHRISTIE

University College London Hospitals, UK

NDIBEER BEAR 1

A B S T R AC T This article weaves research ndings and clinical practice to address ve ethical dilemmas: How to include children in sessions so that they feel listened to, appreciated and not judged; how to attend to childrens feelings without making the focus solely their troubles; how to create a context in which children can express themselves when they cannot nd the words; how to ensure a suitable time, place and relationship for talking; and how to create a safe context for respectful co-ordination between the different views of children and adults. A practical example including transcripts from sessions is presented. The authors show how a toy bear joining two therapists in a reecting team can create opportunities for a 10-year-old girl and her parents to voice their different views and hear the different perspectives of each other. The parents, who generously agreed to share details of their family sessions, offered useful feedback on this write-up, suggesting that this article may be useful for staff and parents who join therapists in a playful approach to reecting teams with children. K E Y WO R D S children in family therapy, play in family therapy, reecting teams, toys in therapy

T E N - Y E A R - O L D L A U R A T I M M S 2 had recovered from treatments for bone cancer that extended over almost a year. One of us (Deborah), a clinical psychologist, had worked with Laura when she was an inpatient on a childrens cancer ward, helping her ght against overwhelming fear and aversion associated with the gruelling effects of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Although the cancer was successfully treated, Laura was left unable to extend her leg from the knee and therefore required further orthopaedic surgery to enable her to walk. Laura had told her parents that she did not want surgery ever again

Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry Copyright 2007 SAGE Publications Vol 12(2): 211222. DOI: 10.1177/1359104507075922 www.sagepublications.com 211

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

and was also refusing to attend the hospital. Wanting the best for Lauras future, her parents were desperate for her to attend an assessment with the orthopaedic surgeon to give her every opportunity to walk. Having appreciated Deborahs work with Laura in the past, they asked for her help.

Since Laura was refusing to come to the hospital, where our team is based, our rst dilemma was how to engage her. Deborah knew that Laura had a yellow bear called Twinkle who had comforted her through previous treatments. She therefore wrote to Laura inviting her to come and meet with her and her team. She explained that we had heard from her parents that she did not want to come to hospital and that one of the team (Glenda) had a blue bear called Ndibeer who had helped another girl with a bent leg. We added that Ndibeer would like to meet Twinkle who was therefore also invited to our meeting.

Laura arrived with her parents and Twinkle. Deborah talked with the family while the team, Glenda and Ndibeer, sat behind her. Deborah began by introducing us all, including Ndibeer. Twinkle (assisted by Laura) waved at Ndibeer. Glenda helped Ndibeer to wave back. Deborah spoke rst with Laura: Deborah: So Laura, lets imagine it is now 4 oclock and you are going away from our meeting today and you say to your mother and father, I am really pleased I went. Things are more sorted out now. What did we talk about here, Laura? What did we sort out? Laura: I want to talk about things going well at school. I dont want to talk about the operation. Deborah: OK. So you want to talk about all the good things at school not the operation. And Mr and Mrs Timms, what about you? What if . . . Mr Timms: We want to talk about the operation. Mrs Timms: Yes we want to start planning. We have an appointment with the surgeon.

G L E N DA F R E D M A N

is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist and accredited Systemic Psychotherapist. She works with sick children and their families at University College London Hospitals. She is director of systemic training and systemic supervisor with Camden and Islington Mental Health and Social Care Trust where she also works with services for adults, elders and people with learning disability.

C O N TA C T : Glenda Fredman, Department of Clinical Psychology (Camden and Islington Mental Health and Social Care Trust), Hunter Street Health Centre, 8 Hunter Street, London WC1N 1BN, UK. [E-mail: glenda.fredman@blueyonder.co.uk] D E B O R A H C H R I S T I E is a Consultant Clinical Psychologist and honorary Senior Lecturer at University College London Hospitals. She has a background in neurobiology, neuropsychology and paediatric clinical psychology. She has specialized in adolescent medicine and has a special interest in how systemic therapies can nd ways to help young people and their families live with chronic conditions. C O N TA C T : Deborah Christie, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychological Services, University College London Hospitals, 250 Euston Road, London, UK. [E-mail: deborah.christie@uclh.nhs.uk] NDIBEER BEAR

was a member of the reecting team.

212

FREDMAN ET AL.: REFLECTING TEAMS WITH CHILDREN

Before Deborah could say anything, Lauras parents began to give an update on the plans for surgery and the problems with Lauras leg. During their talking, Laura groaned and whined, writhing in her wheelchair, I dont want to . . . not my operation . . . noooo . . . oh no . . . I dont . . . not my operation . . . I dont want another operation . . . I (Glenda) found it too distressing to listen and impossible to hear Lauras parents through her groaning and whining. In my inner talks (Andersen, 1998) I was saying I cannot bear this . . . I have to stop Deborah . . . This is awful . . . but will I undermine Deborah? And then what about giving the parents a chance to state their view? I did not know how to go on.

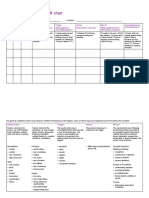

In these rst few minutes of our joint session a number of ethical dilemmas challenged our efforts to work collaboratively and respectfully with both Laura and her parents. Research that invites childrens own accounts of their experience of family therapy echoes these ethical dilemmas and informs the ve questions below that guide our work with children in family sessions. In our work with this family, we found Tom Andersens Reecting Team methods (Andersen, 1987, 1991; Friedman, 1995) a useful vehicle to address these questions:

How can we include children in sessions so they feel listened to, appreciated and not judged?

Research shows that children want to be included and heard in family therapy sessions. Stith, Rosen, McCollum, Coleman, and Herman (1996) interviewed children between the ages of 5 and 13 and found that they preferred to participate through play and activity and that they did not want the focus to be solely on their troubles. The 11- to 17-yearolds in Strickland-Clark, Campbell, and Dalloss (2000) study all emphasized the importance of being listened to and reported that they were unable to listen or express themselves with words when they were experiencing strong emotions, which heightened their feeling of not being heard. The 7- to 12-year-olds in Joness (2003) study also wanted to be included in the therapy room, found it upsetting to be excluded in a session and valued being listened to. Lobatto (2002) found that the children (aged 8 to 12) in her study valued their viewpoint being represented to their family by the therapist. She further found that children felt included when they were not judged or reprimanded and excluded if they felt their feelings were not attended to. Several studies show that children speak far less than parents in family sessions (Friedlander, Highlen, & Lassiter, 1985; Mas, Alexander, & Barton, 1985) and that therapists speak more often to parents than children (Postner, Guttman, Sigal, Epstein, & Rakoff, 1971). Korner and Brown (1990) report that 40% of family therapists never invite children to the session and 31% invited children to the session without involving them in the therapy. McAdam (1995) and Wilson (1998) address how children are more commonly talked about rather talked with in therapy. Jones (1995) distinguishes the need to offer the child the condence to be heard within the family rather than a special condential relationship outside the family with the therapist, and Lewis and Kavanagh (1995) note that play materials are often used in sessions to keep children quiet or occupied while the therapist works with the adults in the presence of the child. Explanations for excluding children from therapeutic conversations include therapists personal discomfort working with children (Lund, Zimmerman, & Haddock, 2002; Rober, 1998); low expectations of children as conversational partners (Cederbrog, 1997) including prejudices about childrens cognitive immaturity, inaccessibility of language or the wish to protect children from talking about upsetting issues (McAdam, 1995) and the difculty developing a working therapeutic alliance or nding a relevant focus in which the child can become actively engaged (Wilson, 1998).

213

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

Later we show how we involve a toy bear, Ndibeer, as a reecting team member to invite Laura to participate with us through play. Following the reecting team method, the team sat in the same room as the family and listened to the therapist (Deborah) talking with the family. Ndibeer was allocated the task of listening respectfully to Laura, throughout holding in mind the question, What does she want me to appreciate about her and her situation? At intervals, the team talked with each other and not directly to the family. Thus we did not look at the parents or Laura when we talked, to free them from the obligation to listen or respond and thereby allow their minds to go other places (Andersen, 1992a). Our intention was to present our reections as offerings rather than obligations to respond, thereby giving the listener the opportunity to turn away or refuse our offers. Since toy bears cannot speak, Glenda reected Ndibeers views as well as her own. In this way we created the opportunity to offer multiple perspectives reecting the views of all family members. Ndibeer was primed to witness and tentatively reect Lauras expressions following his observations with speculative questions. At all times team members were careful to restrain themselves from negative connotations.

How can we show children that we are attending to their feelings without making the focus solely their troubles?

Guided by Tom Andersens (1992b) approach we tried to talk about what people say and not what we believe they mean by what they say (p. 90). We were also careful to comment only on what we heard and not what we did not hear, and to tread carefully with reference to what we saw. Thus we avoided interpreting or ponticating about the hidden meanings of peoples expressions. We tried to start with something people expressed during the conversation rather than drawing from other contexts. Holding in mind questions like What might her groaning voice want to say if it could speak? (Andersen, 1995), Ndibeers task was to attend to and witness Lauras feelings not to interpret them. This is how we went on:

Glenda: Deborah, I am very sorry to interrupt you but Ndibeer keeps groaning in my ear and I cant hear or concentrate on what people are saying. He says he is very upset. He says you have not been listening to Laura. Deborah (facing the team): Oh . . . yes I know . . . (Laura stops groaning and listens carefully focusing her eyes on the bear.) Glenda: Yes. He says that Laura has said she does not want to talk about the operation and now you are talking about the operation. Laura (calling out): Yes you didnt listen. You upset me. I said I did not want to talk about the operation. You didnt listen. Deborah: Thank you. Uhm . . .

How can we create a context in which children can express themselves especially when they cannot nd the words?

Booth and Booth (1996) describe how we can loan words to people who do not have a lot of words, which does not have to involve putting words in their mouths or making them feel incompetent. Above we have shown how the bear enabled Lauras groaning voice and her whining voice to nd the words to communicate what she wanted to say. In the reecting conversation with the team, Ndibeer witnesses Lauras experience by

214

FREDMAN ET AL.: REFLECTING TEAMS WITH CHILDREN

reecting Lauras own words that she does not want to talk about the operation. He adds a few words of his own, upset that he attributes to himself thus taking care not to offer potentially unwanted interpretations of Lauras feelings, and not listening. Laura takes on these words as her own you didnt listen and you upset me and goes on to use them many times in the course of our work with her. By reecting Lauras perspectives, Ndibeer also frees Deborah to take the perspective of the parents:

Deborah (looking at Ndibeer): Does Ndibeer have any ideas about what I can do? Laura does not want to talk about the operation Lauras mum and dad want to talk about the operation . . . Glenda: Well I dont think this is up to Ndibeer, Deborah he is only a bear. He cant make decisions for us. Deborah: No . . . of course . . . Glenda: But we could talk to Laura about talking about the operation.

How can we know this is a suitable time, place and relationship for talking?

We do not assume that everyone present wants to talk about the same things or indeed wants to talk with us at all. Therefore we talk only about what people want to talk about and not what they do not want to talk about (Andersen, 1995). Following Fredmans (1997) approach to talking about talking with children and families, we always talk about whether we should talk and if so, when and who prefers to talk with whom about what. We ask about who has already talked about what with whom. We explore all peoples views on the effects of talking on people and relationships and what they consider the best circumstances for talking. In this way we position the client as the expert (Anderson & Goolishian, 1992) on how we go on with talking. Here is how we go on to talk about talking with Laura and her family:

Glenda: Deborah, Ndibeer is now telling me he has an idea. He says maybe Laura could give you a red card when you must stop talking like in football or she could put up her hand like a trafc policeman to say, Stop? Laura: I could have three cards red, orange and green red is stop talking, amber is be careful what you are saying and green is carry on. Deborah: Thats a great idea. Glenda: I am sorry Deborah, Ndibeer keeps talking in my ear so I cannot concentrate. Deborah: What is he saying now? Glenda: He is asking if Laura can make those cards and he is asking what she will call them. He thinks other children here on the ward would like to use them too. Laura: Lauras Emotion Cards. I want other children to use them. Deborah: That is a wonderful idea Laura. And would you like to make them? I think I know where we have red, orange and green paper. Laura: (Nods in agreement.) Deborah went on to talk with Laura and her parents about talking. She explored what they thought would happen if we carried on talking about the good things at school and if they talked about the operation. Mr and Mrs Timms were adamant that this operation had to be scheduled before the end of the summer holidays and wanted to get on with

215

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

planning. For them, not talking about the operation would mean Laura not walking. We learnt that some talking had been done between Laura and her mother in the bath at home when Laura had told her mother she would have the operation. Laura said if we talked about school she would be happy. She did not want the operation and talking about it made her scared and upset.

In systemic therapy we hold joint meetings with children and adult carers to enable the perspectives of all to be voiced and heard and to create opportunities to go on with them in ways that t with all involved. Wilson (1998) emphasizes the right of all participants in the conversation to speak and listen as they wish. He identies the therapists task to invite each persons views and to offer a link between their different accounts, raising the voice of the child without drowning out the parents. He notes that this is no easy task in a context where adults and children commonly have conicting needs or where blame or criticism interfere with the different accounts people tell. Burnham (1998) calls this process of co-ordination systemic rapport, the process whereby the therapist tries to connect with one person while maintaining the possibility of connecting with the others in the family and enabling those others to connect with each other. Research points to the challenge for the therapist of enabling an even-handed dialogic exchange between parents and children in joint sessions when children and adults have differing levels of linguistic and cultural competence, cognitive ability and power to consent to treatment (Lobatto, 2002). For example several children in Strickland-Clark et al.s (2000) study found it difcult to speak out in sessions because they were concerned about offending other family members, inviting bad reactions or getting things wrong and the children in Lobattos study reported feeling too central at times and at other times excluded. Hence we are pointed towards the next ethical dilemma.

How can we create a safe context for respectful co-ordination between the different views of children and adults?

Systemic practice does not necessitate that everyone involved talk about everything all together at the same time. It is not unusual for systemic practitioners to divide the original group into smaller talking units to enable those who want to, to talk about the issue while excusing those who do not want to talk (Andersen, 1995). Laura agreed that Deborah talk to the parents about the operation while she went outside to create Lauras Emotion Cards. In the following session we also talked with Laura without her parents. In both Strickland-Clark et al.s (2000) and Lobattos (2002) studies children mentioned the advantage afforded by having an advocate present in the sessions, someone to stick up for me . . . say it for me . . .. For some this could be a sibling, while others preferred time alone with the therapist or for the therapist to represent their viewpoint to their family. In our work with the Timms family, Ndibeer advocated for Laura. This freed Deborah to attend to the parents perspectives while Glenda could take a meta-perspective on all their views. We present this process in the following transcript from our second meeting.

Since the family agreed that they preferred to start with separate talk, Laura left the room to supervise both bears, Ndibeer having requested time on his own with his new bear friend. Mr and Mrs Timms then told us that they wanted Laura to have the operation. Mrs Timms said that Laura had been invited to be a bridesmaid and she wanted her to walk down the aisle with the retinue. They said that they wanted Laura to talk to us on her own so she can get it all out of her system like last time . . . but whatever happens she is having the operation and we do not want you to tell Laura that it is her choice.

216

FREDMAN ET AL.: REFLECTING TEAMS WITH CHILDREN

When Laura returned with Ndibeer and Twinkle, the bears were sharing an embrace on her lap. Ndibeer returned to his place with the team. Deborah spoke with Laura about all the good things happening at school and then asked Laura if she knew what we were talking about with her parents: Laura: My operation. Deborah: Yes. And your Mum told us you have been invited to be a bridesmaid. Laura (grinning) Glenda: Deborah, Ndibeer wants to know what colour dress Laura wants to wear? Laura: Yellow. Glenda: Deborah, I am so sorry but Ndibeer is very talkative today he is now getting very excited about this wedding. He wants to know if Laura wants to walk down the aisle or if it is OK to go in her wheelchair. Laura (started to cry and talk at great speed): Thats stupid of course I want to walk I want to walk. I dont want the operation. Nobody is listening to me I keep saying that I dont want the operation and nobody is listening to me. (We sat with Laura as she sobbed.) Glenda: Sorry Deborah but Ndibeer is asking me to ask you if Laura wants the operation to be stopped. Deborah (looking at Glenda as if to say what on earth are you doing!) Laura (began to scream. She threw Twinkle on the oor and wailed): I dont want the operation, I want to walk, I dont want the operation, I want to walk. What am I supposed to do? How can I walk if I dont have the operation? (We sat with Laura as she wept.) Glenda: Ndibeer is very upset Deborah, he says it is not fair. Laura: Its not fair. Why do I have to have another operation? I have already had two operations and I had chemotherapy and I had . . . I had . . . Its not fair. Why cant someone else have an operation? Why should I? Glenda: Deborah, Ndibeer is saying something I dont quite understand, maybe you can work it out? He says none of us are listening to Laura. He says she does not want the operation. Deborah: I know. Laura is being very clear here. She does not want the operation. Glenda: He says that Laura really wants to walk and she understands that to walk she will have to have the operation. Deborah: Yes I see that she wants to walk. Glenda: Ndibeer says that Laura is not saying to stop the operation. She may choose to shout really loud that is our problem and we will have to help the nurses and doctors with that it doesnt bother Laura she may have to shout to let us all know. Ndibeer says Laura wants to walk down the aisle as bridesmaid in her yellow dress. I am not sure I can understand what Ndibeer is going on about? Deborah: I think I do. Laura, what do you think about what Ndibeer says that this is our problem to sort out with the nurses and doctors if you shout it doesnt mean you are not having the operation. It means you do not want the operation?

217

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

Laura (nodding and sobbing lightly): I threw Twinkle on the oor. Deborah (picking up Twinkle and handing him to Laura): I know. Laura (sobbing and kissing Twinkle): Sorry Twinkle . . . sorry Twinkle. Deborah (speaking very softly): I think Twinkle will understand, Laura. Sometimes we have a go at the ones we love most because they are there for us we dont mean to hurt them. When we rejoined with Laura and her parents, Deborah explained that Laura had been very clear with us that she wanted to walk down the aisle as a bridesmaid in a yellow dress. Mrs Timms told us, laughing affectionately, Well I am not sure it can be yellow. Thats not up to us. Deborah went on that Laura was very clear with us that she did not want the operation and we all had to show we had heard that and that we understood that it is not fair. Laura had also said she knows that she has to have an operation to be able to walk so she was not asking us to stop the operation. Laura told her mother tearfully that she had thrown Twinkle on the oor. Her mother was very sympathetic and said she was sure Twinkle understands.

To be able to voice their different views in joint conversations the people involved need a safe therapeutic context marked by respect and appreciation of everyones perspectives. As the children in the previously cited research have shown, being respected includes being heard and listened to. Rober (1998) reminds us that nobody can be as silent as a child, regardless of how much noise she makes and that most people will censor or withhold their talk until they feel safe to express themselves. Our challenge was to create a therapeutic context where Laura could feel safe to express herself competently. Towards this end McAdam (1995) suggests starting with the child and/or inviting someone in the family to talk with the childs voice and entering the childs grammar by trying to see their world as they see it, at their developmental level. Fredman (1997) proposes joining the childs language and acknowledging the childs expertise. Rober offers us guidelines for making a safe therapeutic culture with children which include: Being prepared to tolerate uncertainty, chaos and confusion and our inability to control everything going on in a session; getting to know the positive aspects of the child before addressing the worries of the parents and opening space for the notyet-said through play. Many family therapists identify the value of play. Jones (1995) discusses how play enables people to experiment and explore different ways of relating and being as well as creating opportunities for all participating to take different person positions. Ndibeer gave Glenda the opportunity to talk from the position of therapist and child. Arad (2004) demonstrates how creating a fun, nonthreatening atmosphere can facilitate the engagement and participation of children of all ages in the therapeutic process thereby enabling the expression of conicting feelings and beliefs within a safe context. Through her playful Animal Attribution Storytelling technique she shows how play makes it possible for taboo subjects to be explored in a context of as if thereby opening space for possible new solutions. Play can also protect adults from a tendency to understand too quickly. It is often through just playing with what children bring to therapy that understanding emerges (Rober, 1998). Thus it was only the toy bear Ndibeer who could ask the question, Does Laura want the operation to be stopped? as we all understood that He is only a bear. He cant make decisions for us. By bringing forth the unthinkable or the unsayable (Dowling, 1993) in this way, we were able to enter into Lauras logics of meaning and hence understand that it was crucial that we acknowledge that Laura did not want the operation but that she would have the operation only

218

FREDMAN ET AL.: REFLECTING TEAMS WITH CHILDREN

because she wanted to walk and it was our responsibility to show that we recognized the unfairness of her predicament.

Reecting teams with children

Our intention was to create opportunities for Laura and her parents to voice their different views and for each to hear the different perspectives of the other. We have found that using reecting teams and inviting reecting processes (Andersen, 1992a) facilitate this process. Inviting the people present to shift between listening and talking about the same issues moves them between inner talks while listening and outer talks while talking (Andersen, 1998). These different positions can offer the people present different perspectives. The juxtaposition of these different perspectives can invite the person to make new connections between these different perspectives thereby creating opportunities for new stories to emerge. Thus with the perception of difference, new contexts can evolve, giving new meanings to old ideas (Bateson, 1979). However, because of the emphasis on oral language, family sessions with reecting teams tend to favour the adults and are at risk of marginalizing the child. Conversations between team members can become too abstract or complex thus distancing children who cannot comprehend. Johannesen, Rieber, and Trana (1998) therefore have developed the reecting puppet-show as a tool to talk through problems with children and families. Choosing puppet characters the family would be able to identify with, they perform stories for the children and parents. Their intention is that the child should be able to recognize themselves in the story and that the metaphor conveys hope of a better future. In this way Johanessen et al. have adapted the reecting team approach to the childs level of linguistic competence and mode of expression. Although the teams talking to each other about family members in the third person can free the adults to listen without the obligation to respond, placing the child in the third person can have more marginalizing effects. Children often experience adults (like parents, teachers or doctors) talking about them in evaluating and sometimes criticizing contexts. Therefore talking about the child in front of the child could risk the team creating a context too similar to those contexts in which the child has felt judged or their voice silenced. Giving a toy the opportunity to talk about the child can offer a different positioning from conventional reecting team practice. At the start of our work with this family we noted that Laura paid special attention to the words of Ndibeer and later, during her treatments, her groaning voice (expressing pain frustration or discomfort) would usually still to allow her to listen to the words of the toy animal. Rober (1998) points to the potential for play to connect the worlds of adults, marked by abstract thinking and words, with the more concrete and nonverbal worlds of children. Johannesen et al. (1998) offer the reecting puppet-show approach as a method that addresses children and their parents at the same time. Focusing on childrens resources and catching their attention better than ordinary team reections, the reecting puppetshow more readily involved the children who found this approach less threatening. In their examples, the parents also willingly accepted the invitation to participate in the play and both parents and child responded with great pleasure. Although parents responded enthusiastically to Arads (2004) animal play-stories approach, she also reports the discomfort of some parents with such a nonmedical intervention when the rationale for working this way was unclear. Throughout our sessions Laura showed us that she had engaged well with our bear-talk. Every time Glenda spoke for Ndibeer, Laura listened quietly, focusing intently on the bear as if she were drinking in his every word. At the start of the rst meeting she helped Twinkle to

219

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

wave to Ndibeer and later she created a card, Hi bear! Nice to meet you. Through our playful approach we were co-ordinating well with Laura, who agreed to meet with us again. However, when Mr Timms said, after Laura left the room, This has all been very entertaining, but the bottom line is that Laura has to have that operation. As parents we cannot sit back and see our daughter in a wheelchair for life because we let her decide she did not want this operation, we were concerned that our way of working did not t for the parents. Informed by reecting team guidelines (Andersen, 1992a) we take care that our approach with people is not too unusual. Tom Andersen (1992b) says that this should apply to not only what we talk about but also how we talk. How clients participate in the conversation can point to whether this talking is appropriately unusual or too different. Whereas bear-talk seemed a t for Laura, it could have been too unusual for her parents in the rst session. Johannesen et al. (1998) suggest that the puppet-show has to contain something familiar and something new. Thus it ought to present a difference that makes a difference but not so different from their experience that the family is unable to connect with it. Gross (1995) reminds us that playful techniques can only be introduced in a climate where the therapist has established rapport with the parents in relation to the focus of the work, the meaning of the professionals role and its limits and a shared view about the childs participation in the work. Arad (2004) suggests that for some parents, explaining the therapeutic rationale for a playful approach can promote their engagement. In retrospect we wondered whether it would have helped Mr and Mrs Timms to feel more connected with the rst session if we had spent more time talking with them about the rationale for including Ndibeer in the team.3 However, we were fortunate that both parents were clearly committed throughout our work with them to ensuring the best outcome for their daughter, and in retrospect we were able to see how hard the parents had worked to understand our approach and to join the grammar that was engaging their daughter. For example, as the family was leaving the rst session we overheard Mr Timms asking Laura, Is Ndibeer a girl or a boy? and when she pointed out that the bear was wearing a dress, his seriously pondering aloud, So why are they calling him he? Very strange . . .. We also noted Mrs Timms reassuring Laura that Twinkle understands and Mr Timms calling out, Goodbye Ndibeer at the end of our second session. Lauras parents generous willingness to join the grammar that they could see was engaging their daughter, reassured us that they would become valuable contributors to her team. Arad (2004) discusses how play can facilitate dialogue between family members and provide working metaphors that later become an integral part of the therapy sessions and of family lore. Ndibeer has been incorporated not only into therapy and family conversations with Laura but his presence has emerged in other contexts, for example when the surgeon seemed unable to denitively answer a question about prognosis, Mr Timms reected, to the bemusement of the surgeon, I suppose that is a question for Ndibeer. Ndibeers involvement with Laura has also empowered other toy animals to form reecting teams with other psychologists in our service.

Epilogue

Clinical Psychologist, Ruth Drake and another team member, Ned, a green cloth donkey, continued to work with Laura through two further episodes of orthopaedic surgery and intensive physiotherapy. Talking through Ruth in their reecting conversations, Ned offered different perspectives on the situation, witnessing Lauras experiences and also

220

FREDMAN ET AL.: REFLECTING TEAMS WITH CHILDREN

giving meta-views on the process of therapy when Ruth was unsure how to go on. At rst Laura shouted her way to surgery to show us all that her treatments were not fair. Through the grit and determination of Laura and her parents and the willingness of her doctors and nurses to tolerate the uncertainty, chaos and confusion the situation presented us, Laura went on to dance with her father and grandfather at the family wedding. She is now walking.

Notes

1. Toy member of reecting team. 2. Names have been changed to protect condentiality. 3. Mr Timms stated this more elegantly in his letter giving permission for this publication: The only comment I would make is that my wife and I were quite bemused by the approach when you started using it. While you will know that we played along with this, our feeling is that it would probably be worth brieng the parents on the approach to be taken in advance in order to avoid any misunderstandings.

References

Andersen, T. (1987). The reecting team: Dialogue and metadialogue in clinical work. Family Processes, 26, 415428. Andersen, T. (1991). The reecting team: Dialogues and dialogues about the dialogues. New York, Norton. Andersen, T. (1992a). Reections on reecting with families. In S. McNamee & K.J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as social construction (pp. 5468). London: SAGE Publications. Andersen, T. (1992b). Relationship, language and pre-understanding in the reecting process. A.N. Z. Journal of Family Therapy, 13(2), 8791. Andersen, T. (1995). Reecting processes: Acts of informing and forming you can borrow my eyes, but you must not take them away from me! In S. Friedman (Ed.), The reecting team in action. collaborative practice in family therapy (pp. 137). New York: Guilford Press. Andersen, T. (1998). One sentence of ve lines about creating meaning: In perspective of relationship, prejudice and bewitchment. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 9, 7380. Anderson, H., & Goolishian, H.A. (1992). The client is the expert: A not-knowing approach to therapy. In S. McNamee & K.J. Gergen (Eds.), Therapy as social construction (pp. 2539). London: SAGE Publications. Arad, D. (2004). If your mother were an animal, what animal would she be? Creating play-stories in family therapy: The Animal Attribution Story-telling Technique (AASTT). Family Process, 43, 249263. Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature. London: Wildwood Press. Booth, T., & Booth, W. (1996). Sounds of silence: Narrative research with inarticulate subjects. Disability and Society, 11, 5569. Burnham, J. (1998). Foreword. In J. Wilson (Ed.), Child-focused practice: A collaborative systemic approach (pp. xiixvi). London: Karnac. Cederborg, A.C. (1997). Young childrens participation in family therapy talk. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 25, 2838. Dowling, E. (1993). Are family therapists listening to the young? A psychological perspective. Journal of Family Therapy, 15(4), 403412. Fredman, G. (1997). Death talk: Conversations with children and families. London: Karnac.

221

CLINICAL CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 12(2)

Friedlander, M.L., Highlen, P.S., & Lassiter, W.L. (1985). Content analytic analysis of four expert counselors approaches to family treatment: Ackerman, Bowen, Jackson and Whitaker. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32, 171180. Friedman, S. (Ed.). (1995). The reecting ream in action: Collaborative practice in family therapy. New York: Guilford Press. Gross, V. (1995). A child aware approach in systemic practice. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 6,189200. Johannesen, T.L., Rieber, H., & Trana, H. (1998). The reecting puppet-show: A new way of communication with children in family therapy. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 9, 123138. Jones, A. (1995). The wisdom of childrens ways of wondering. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 6, 201226. Jones, F. (2003). An empirical exploration of childrens descriptions of their experiences in family therapy. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 14, 151166. Korner, S., & Brown, G. (1990). Exclusion of children from family psychotherapy: Family therapists beliefs and practices. Journal of Family Psychology, 3, 420430. Lewis, P., & Kavanagh, C. (1995). Play as dialogue, giving voice to the child in family therapy. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 6, 227240. Lobatto, W. (2002). Talking to children about family therapy: A qualitative research study. Journal of Family Therapy, 24(3), 330343. Lund, L.K., Zimmerman, T.S., & Haddock, S.H. (2002). The theory, structure, and techniques for the inclusion of children in family therapy: A literary review. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28, 445454. McAdam, E. (1995). Tuning into the voice of inuence: The social construction of therapy with children. Human Systems: The Journal of Systemic Consultation and Management, 6, 171188. Mas, C.H., Alexander, J.F., & Barton, C. (1985). Modes of expression in family therapy: A process study of roles and gender. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 11, 411445. Postner, R.S., Guttman, H.A., Sigal, J.J., Epstein, N.B., & Rakoff, V.M. (1971). Process and outcome in conjoint family therapy. Family Process, 10, 451474. Rober, P. (1998). Reections on ways to create a safe therapeutic culture for children in family therapy. Family Process, 3, 201213. Stith, S.M., Rosen, K.H., McCollum, E.E., Coleman, J.U., & Herman, S.A. (1996). The voices of children: Preadolescent childrens experience of family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 22, 6986. Strickland-Clark, L., Campbell, D., & Dallos, R. (2000). Childrens and adolescents views on family therapy. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(3), 324341. Wilson, J. (1998). Child-focused practice: A collaborative systemic approach. London: Karnac.

222

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Conquering Your Child's Chronic Pain: A Pediatrician's Guide for Reclaiming a Normal ChildhoodVon EverandConquering Your Child's Chronic Pain: A Pediatrician's Guide for Reclaiming a Normal ChildhoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Play TherapyDokument6 SeitenThesis Play Therapyafktbwqoqnevso100% (1)

- Child Diagnosis With ADHDDokument28 SeitenChild Diagnosis With ADHDpsiho978Noch keine Bewertungen

- Being There, Experiencing and Creating Space For Dialogue: About Working With Children in Family Therapy by Peter RoberDokument14 SeitenBeing There, Experiencing and Creating Space For Dialogue: About Working With Children in Family Therapy by Peter RoberOlena Baeva0% (1)

- How Well Did I Hear - FinalDokument9 SeitenHow Well Did I Hear - Finalapi-348757120Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cool Hart Ship Man 2017Dokument14 SeitenCool Hart Ship Man 2017Ana MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mansigue, Regie Mark-Clinical Internship Requirements CompilationDokument42 SeitenMansigue, Regie Mark-Clinical Internship Requirements CompilationRegie Mark MansigueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inquiry Paper Third DraftDokument5 SeitenInquiry Paper Third DraftJessicaHernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Right-Brained Children in a Left-Brained World: Unlocking the Potential of Your ADD ChildVon EverandRight-Brained Children in a Left-Brained World: Unlocking the Potential of Your ADD ChildBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (11)

- Play Therapy With Children - Modalities For ChangeDokument279 SeitenPlay Therapy With Children - Modalities For ChangePostitulo Internacional100% (2)

- Not Just Spirited: A Mom's Sensational Journey with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)Von EverandNot Just Spirited: A Mom's Sensational Journey with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (11)

- Overcoming Borderline Personality Disorder - A Family Guide For Healing and ChangeDokument415 SeitenOvercoming Borderline Personality Disorder - A Family Guide For Healing and ChangeMariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How it Feels to be You: Objects, Play and Child PsychotherapyVon EverandHow it Feels to be You: Objects, Play and Child PsychotherapyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greater Expectations: Living with Down Syndrome in the 21st CenturyVon EverandGreater Expectations: Living with Down Syndrome in the 21st CenturyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applications of Family and Group Theraplay PDFDokument317 SeitenApplications of Family and Group Theraplay PDFLarisa Giuris100% (1)

- Drawing A Family MapDokument14 SeitenDrawing A Family MapJack Greene100% (5)

- Raising Freakishly Well-Behaved Kids: 20 Principles for Becoming the Parent your Child NeedsVon EverandRaising Freakishly Well-Behaved Kids: 20 Principles for Becoming the Parent your Child NeedsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Parenting Through Illness: Help for Familes When a Parent Is Seriously IllVon EverandParenting Through Illness: Help for Familes When a Parent Is Seriously IllNoch keine Bewertungen

- Children and Youth Services ReviewDokument6 SeitenChildren and Youth Services ReviewMonika Meilutė-RibokėNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Thearapy byDokument4 SeitenFamily Thearapy byMahammad RafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Care of Sick ChildDokument11 SeitenCare of Sick ChildMiu MiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Spirit Catches YouDokument6 SeitenThe Spirit Catches YouJulia Hart100% (2)

- Raising Great Parents: How to Become the Parent Your Child Needs You to BeVon EverandRaising Great Parents: How to Become the Parent Your Child Needs You to BeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Use of Play For Assessment and Therapy The Case of A Child With Selective MutismDokument13 SeitenThe Use of Play For Assessment and Therapy The Case of A Child With Selective MutismdiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Children: It's Not Always the Parent's FaultVon EverandProblem Children: It's Not Always the Parent's FaultNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Addiction and Recovery Through a Child's Eyes: Hope, Help, and Healing for FamiliesVon EverandUnderstanding Addiction and Recovery Through a Child's Eyes: Hope, Help, and Healing for FamiliesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inclusion ProjectDokument9 SeitenInclusion ProjectEllishya BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Family Therapy: Advanced ApplicationsVon EverandMedical Family Therapy: Advanced ApplicationsJennifer HodgsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper Tigers Film ReflectionDokument4 SeitenPaper Tigers Film Reflectionapi-656458116Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lyle Torrant 2903Dokument4 SeitenLyle Torrant 2903api-352990469Noch keine Bewertungen

- Play Therapy A ReviewDokument17 SeitenPlay Therapy A ReviewAron MautnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Transgender Child: A Handbook for Parents and Professionals Supporting Transgender and Nonbinary ChildrenVon EverandThe Transgender Child: A Handbook for Parents and Professionals Supporting Transgender and Nonbinary ChildrenNoch keine Bewertungen

- (The Guilford Family Therapy) Howard A. Liddle, Douglas C. Breunlin, Richard C. Schwartz - Handbook of Family Therapy Training and Supervision-The Guilford Press (1988)Dokument459 Seiten(The Guilford Family Therapy) Howard A. Liddle, Douglas C. Breunlin, Richard C. Schwartz - Handbook of Family Therapy Training and Supervision-The Guilford Press (1988)Maria Paz Widmer100% (2)

- Tired Teens: Understanding and Conquering Chronic Fatigue and POTSVon EverandTired Teens: Understanding and Conquering Chronic Fatigue and POTSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paul Holmes, Steve Farnfield - The Routledge Handbook of Attachment - Implications and Interventions-Routledge (2014)Dokument205 SeitenPaul Holmes, Steve Farnfield - The Routledge Handbook of Attachment - Implications and Interventions-Routledge (2014)Pamela Fontánez100% (4)

- Now Say This: the right words to solve every parenting dilemmaVon EverandNow Say This: the right words to solve every parenting dilemmaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Play TherapyDokument26 SeitenPlay TherapypastellarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blog Post 12Dokument3 SeitenBlog Post 12Tazeen SiddiquiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waiting and RelatingDokument8 SeitenWaiting and RelatingAnindita MajumdarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buttross, Susan - Understanding ADHDDokument141 SeitenButtross, Susan - Understanding ADHDPete Bilo83% (6)

- Small Wonders: Healing Childhood Trauma With EMDRVon EverandSmall Wonders: Healing Childhood Trauma With EMDRBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Play Therapy in Dealing With Bereavement and Grief in Autistic Child: A Case Study by PrabhaDokument3 SeitenPlay Therapy in Dealing With Bereavement and Grief in Autistic Child: A Case Study by PrabhaSeshan RanganathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rambo Rhoades 2010 Intro Systemic Family TherpayDokument25 SeitenRambo Rhoades 2010 Intro Systemic Family TherpaynanceagrwllNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psilocybin Treatment of Childhood Schizophrenia Utilizing LSD and PsilocybinDokument16 SeitenPsilocybin Treatment of Childhood Schizophrenia Utilizing LSD and PsilocybinIxulescu HaralambieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Therapy Two Case StudiesDokument17 SeitenFamily Therapy Two Case StudiesjadnberbariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feelings Run in The Family: Kin Therapeutics and The Configuration of Cause in ChinaDokument22 SeitenFeelings Run in The Family: Kin Therapeutics and The Configuration of Cause in ChinambadaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strength Based ApproachDokument4 SeitenStrength Based ApproachRonn SerranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Care-Therapy For Children ThePoet016116Dokument257 SeitenCare-Therapy For Children ThePoet016116Emilia Iatica100% (1)

- Running Head: Supporting and Caring For People With DementiaDokument10 SeitenRunning Head: Supporting and Caring For People With DementiaNilavi Singha KaushalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Please Explain Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy To Me: A Complete Guide to Preparing a Child for SurgeryVon EverandPlease Explain Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy To Me: A Complete Guide to Preparing a Child for SurgeryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Paper On AdhdDokument6 SeitenResearch Paper On Adhdapi-212848090Noch keine Bewertungen

- Little Girls Can Be Mean: Four Steps to Bully-proof Girls in the Early GradesVon EverandLittle Girls Can Be Mean: Four Steps to Bully-proof Girls in the Early GradesNoch keine Bewertungen

- David A. Crenshaw PHD - Therapeutic Engagement of Children and Adolescents - Play, Symbol, Drawing, and Storytelling Strategies (2008, Jason Aronson, Inc.)Dokument176 SeitenDavid A. Crenshaw PHD - Therapeutic Engagement of Children and Adolescents - Play, Symbol, Drawing, and Storytelling Strategies (2008, Jason Aronson, Inc.)mamta100% (1)

- How I Provide A Service For Young People With Asperger Syndrome (1) - Let's Get OnDokument2 SeitenHow I Provide A Service For Young People With Asperger Syndrome (1) - Let's Get OnSpeech & Language Therapy in PracticeNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Give Your Kids A Lift: 9 Divine Life Saving ToolsVon EverandHow To Give Your Kids A Lift: 9 Divine Life Saving ToolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- LGBTChildren Family Support BriefDokument12 SeitenLGBTChildren Family Support BriefLina KostarovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reducing Reactive Aggression in Schoolchildren Through Child, Parent, and Conjoint Parent-Child Group Interventions - An Efficacy Study of Longitudinal OutcomesDokument20 SeitenReducing Reactive Aggression in Schoolchildren Through Child, Parent, and Conjoint Parent-Child Group Interventions - An Efficacy Study of Longitudinal OutcomesFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoDokument12 SeitenThe Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applying Resistance Theory To Depression in Black WomenDokument14 SeitenApplying Resistance Theory To Depression in Black WomenFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taking It To The Streets Family Therapy andDokument22 SeitenTaking It To The Streets Family Therapy andFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Systemic About Systemic Therapy? Therapy Models Muddle Embodied Systemic PRDokument17 SeitenWhat Is Systemic About Systemic Therapy? Therapy Models Muddle Embodied Systemic PRFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Presence of The Third Party: Systemic Therapy and Transference AnalysisDokument18 SeitenThe Presence of The Third Party: Systemic Therapy and Transference AnalysisFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relationships, Environment, and The Brain: How Emerging Research Is Changing What We Know About The Impact of Families On Human DevelopmentDokument12 SeitenRelationships, Environment, and The Brain: How Emerging Research Is Changing What We Know About The Impact of Families On Human DevelopmentFausto Adrián Rodríguez López100% (1)

- Eia Asen: Multiple Family Therapy: An OverviewDokument14 SeitenEia Asen: Multiple Family Therapy: An OverviewFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disarming Jealousy in Couples Relationships: A Multidimensional ApproachDokument18 SeitenDisarming Jealousy in Couples Relationships: A Multidimensional ApproachFausto Adrián Rodríguez López100% (2)

- 1467-6427 00198Dokument14 Seiten1467-6427 00198Fausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handwritten Digit Recognition Using Image ProcessingDokument2 SeitenHandwritten Digit Recognition Using Image ProcessingBilal ChoudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards " Asian Paints" (With Reference To Hightech Paint Shopee, Adoni)Dokument7 SeitenA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards " Asian Paints" (With Reference To Hightech Paint Shopee, Adoni)RameshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pe Assignment TopicsDokument2 SeitenPe Assignment Topicsapi-246838943Noch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Writing Professional CommunicationDokument27 SeitenResume Writing Professional CommunicationTalal AwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vice President of Engineering - Shift5Dokument3 SeitenVice President of Engineering - Shift5Shawn WellsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facilitator PDFDokument8 SeitenFacilitator PDFAnand ChoubeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PSYC 4110 PsycholinguisticsDokument11 SeitenPSYC 4110 Psycholinguisticsshakeelkhanturlandi5Noch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Space Lesson PlanDokument5 SeitenPersonal Space Lesson Planapi-392223990Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas ATDokument20 SeitenTugas ATKhoirunnisa OktarianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 3 4th QuarterDokument106 SeitenGrade 3 4th QuarterVivian BaltisotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIE Prospective Students BrochureDokument5 SeitenBIE Prospective Students BrochureparvezhosenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Face To Face Pre-Intermediate Student's Book-Pages-61-99,150-159 PDFDokument49 SeitenFace To Face Pre-Intermediate Student's Book-Pages-61-99,150-159 PDFTruong Nguyen Duy HuuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excretion and HomeostasisDokument31 SeitenExcretion and HomeostasiscsamarinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media and Information Literacy - Lesson 2Dokument1 SeiteMedia and Information Literacy - Lesson 2Mary Chloe JaucianNoch keine Bewertungen

- SASBE Call For PapersDokument1 SeiteSASBE Call For Papersanup8800% (1)

- Lesson PlanDokument2 SeitenLesson PlanSarah AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behaviour Recording Star Chart 1Dokument5 SeitenBehaviour Recording Star Chart 1api-629413258Noch keine Bewertungen

- BSBOPS405 Student Assessment Tasks (Answered)Dokument19 SeitenBSBOPS405 Student Assessment Tasks (Answered)Regine Reyes0% (1)

- Regular Schedule For Senior HighDokument4 SeitenRegular Schedule For Senior HighCecille IdjaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digital Media SyllabUsDokument1 SeiteDigital Media SyllabUsWill KurlinkusNoch keine Bewertungen

- UNIT-III (Gropu Discussion) (MBA-4 (HR)Dokument6 SeitenUNIT-III (Gropu Discussion) (MBA-4 (HR)harpominderNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05.terrace PlanDokument1 Seite05.terrace PlanAnushka ThoratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Katsura PDP ResumeDokument1 SeiteKatsura PDP Resumeapi-353388304Noch keine Bewertungen

- VMGODokument1 SeiteVMGOJENY ROSE QUIROGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Appendix Freud's Use of The Concept of Regression, Appendix A To Project For A Scientific PsychologyDokument2 SeitenProject Appendix Freud's Use of The Concept of Regression, Appendix A To Project For A Scientific PsychologybrthstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Panjab University BA SyllabusDokument245 SeitenPanjab University BA SyllabusAditya SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Lesson Plan SampleDokument13 SeitenScience Lesson Plan SamplePritipriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tpa 1Dokument11 SeitenTpa 1api-501103450Noch keine Bewertungen

- Masuratori Terestre Si CadastruDokument16 SeitenMasuratori Terestre Si CadastruMonika IlunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LKPD SMK Analytical Exposition TextDokument5 SeitenLKPD SMK Analytical Exposition Texthendra khoNoch keine Bewertungen