Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Puericulture Centers PDF

Hochgeladen von

raul_bsuOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Puericulture Centers PDF

Hochgeladen von

raul_bsuCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

REFERENCE AND RESEARCH BUREAU LEGISLATIVE RESEARCH SERVICE

HISTORY OF PUERICULTURE CENTERS1

EARLY BEGINNING AND PERTINENT LEGISLATION IN DIFFERENT COUNTRIES OF THE WORLD As early as 1860, a French physician advocated a special branch of hygiene devoted to promoting the health of infants and children. Under the term puericulture, knowledge about the nutrition and development of small children was extended in France, Germany and England. In France, infant consultation centers were widely established. These clinics were set up under the authority of local public health agencies. Great Britain enacted a Maternity and Child Welfare Act in 1918. In the United States, the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921 authorized federal grants to the states to finance the establishment of well-baby clinics and pre-natal clinics for expectant mothers. Although this US legislation was terminated in 1929 because of opposition from the organized medical profession, it was reinstated in 1935 as a section of the US Social Security Act.

AS PART OF MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH (MCH) LEGISLATION Recognition of the importance of this maternal and child health (MCH) legislation was underscored by its definition as a special title within the Social Security Act, separate from all the other provisions. Since the end of World War II, MCH legislation has become a standard feature of the health laws of virtually every country. Under official policies, the provision of routine examinations, immunizations, nutritional counselling, and often treatment of minor illness, has become a prominent service given at community health centers and small health stations everywhere. Several countries have enacted legislation defining MCH services very broadly, to encompass not only the health protection of infants and mothers, but also the health of school children, adolescents, the extension of family planning, and the education of health personnel on these matters.

Milton Roemer, National Health Systems of the World, Vol. II, Oxford University Press (1993), p. 193.

In Italy for example, a Regional Law of 1979 calls for general preventive health services to mothers and children, multidisciplinary specialized services, emergency obstetric and neonatological care, refresher training for pediatric personnel, and encouragement of breast feeding. Legislation in Bolivia details requirements for MCH services at primary, secondary and tertiary levels. The quality of care by traditional birth attendants and health promoters is regulated. Agencies providing this care must be licensed and supervised by the Ministry of Health. Mothers are ensured legal protection during their reproductive life and the "internationally recognized rights of children" are protected. ESTABLISHMENT OF PUERICULTURE CENTERS IN THE PHILIPPINES 2 It was the first Secretary of Health, Dr. Jose Fabella, who enlisted women's clubs to help him organize puericulture centers all over the country and help raise funds for the support of the centers. The first actual center to serve babies and mothers was set up in 1905 by a group of women led by Concepcion Felix, wife of Felipe Calderon, author of the Malolos Constitution. The women called the center La Gota de Leche. In 1911 when the Hospicio de San Jose was organized to house orphans, babies were cared for, too. Another organization, Liga Nacional Filipina, was seriously working on the reduction of infant mortality, which was 350 deaths for every 1,000 babies born. Dr. Jesus Gabiera in 1913 organized the first formal puericulture (pueri means child and culture means care of).

ACT NO. 2633 (AN ACT APPROPRIATING THE SUM OF ONE MILLION PESOS FOR CERTAIN WORK IN RELATION TO THE PROTECTION OF EARLY INFANCY IN THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, INCLUDING THE ESTABLISHMENT OF "GOTAS DE LECHE") In 1916, Act No. 2633 was enacted, directing health officials to organize puericulture centers all over the country. By December 21, puericulture centers had been set up in the provinces. In 1921, the Public Welfare Commission was tasked to supervise and organize puericulture centers. It was mandated that all centers should have a doctor, a nurse, a midwife and a social worker, all to be paid by the government. Between 1921 and 1926, Fabella mobilized members of the National Federation of Women's Clubs of the Philippines (NFWCP) and put in place 329 puericulture centers in the country. On February 25, 1961, Paz Mendoza Catolico of the NFWCP, with the support of then President Carlos Garcia, organized the National League of Puericulture and Family Planning Centers at a national convention in San Sebastian College in Manila. After 1961, the World Health Organization, the United Nations Children's Fund,

www.inq7.net.

the Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office and provincial governors funded the construction of puericulture center buildings. When Imelda Marcos was governor of Metro Manila, all the puericulture centers in the area were administered by the Metro Manila Commission. Today, pueriuculture centers and the women who used to run them are surviving, but barely. Politicians took advantage of the disarray after the EDSA revolution of 1986. Some took over the buildings and supervision of the centers, while others removed the name puericulture center on billboards and replaced them with day care and health centers. Today, there are 380 active puericulture centers all over the country, including 80 in Rizal and Metro Manila.

HEALTH:HISTORY OF PUERICULTURE CENTERS RRB/LRS RHAB/JGPC/mti 2.06.03

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Story of the Philippines Natural Riches, Industrial Resources, Statistics of Productions, Commerce and Population; The Laws, Habits, Customs, Scenery and Conditions of the Cuba of the East Indies and the Thousand Islands of the Archipelagoes of India and Hawaii, With Episodes of Their Early History; The Eldorado of the Orient; Personal Character Sketches of and Interviews with Admiral Dewey, General Merritt, General Aguinaldo and the Archbishop of Manila; History and Romance, Tragedies and Traditions of our Pacific Possessions; Events of the War in the West with Spain, and the Conquest of Cuba and Porto RicoVon EverandThe Story of the Philippines Natural Riches, Industrial Resources, Statistics of Productions, Commerce and Population; The Laws, Habits, Customs, Scenery and Conditions of the Cuba of the East Indies and the Thousand Islands of the Archipelagoes of India and Hawaii, With Episodes of Their Early History; The Eldorado of the Orient; Personal Character Sketches of and Interviews with Admiral Dewey, General Merritt, General Aguinaldo and the Archbishop of Manila; History and Romance, Tragedies and Traditions of our Pacific Possessions; Events of the War in the West with Spain, and the Conquest of Cuba and Porto RicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- DWSD - Status of SAP Under Bayanihan 1 & 2Dokument2 SeitenDWSD - Status of SAP Under Bayanihan 1 & 2VERA FilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ManginDokument28 SeitenManginKennethSerpidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Ra 11188Dokument1 SeiteSummary Ra 11188atty. xtc2k112Noch keine Bewertungen

- Socio Political and Economic Condition in The PhilippinesDokument32 SeitenSocio Political and Economic Condition in The PhilippinesJuliean Torres AkiatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction Paper: 2019 General Appropriations Act DelayDokument2 SeitenReaction Paper: 2019 General Appropriations Act DelayRonald OngudaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hacienda Luisita: HistoryDokument16 SeitenHacienda Luisita: HistoryaubreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Perspective On The Bayanihan To Heal As One ActDokument15 SeitenLegal Perspective On The Bayanihan To Heal As One ActJUAN GABONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics 2231Dokument2 SeitenEthics 2231Alrom DonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corazon C. Aquino (1986-1992)Dokument8 SeitenCorazon C. Aquino (1986-1992)Rowena LupacNoch keine Bewertungen

- PCGG, BIR Letters Re Marcos Estate TaxDokument3 SeitenPCGG, BIR Letters Re Marcos Estate TaxNami Buan100% (2)

- BonifacioDokument16 SeitenBonifacioRommel SegoviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speech of President Corazon AquinoDokument10 SeitenSpeech of President Corazon AquinoPaul Vergil100% (1)

- Marcos and SocietyDokument15 SeitenMarcos and SocietyMark Quinto100% (1)

- Historical Timeline of Philippine LiteratureDokument6 SeitenHistorical Timeline of Philippine Literaturejoei_velascoNoch keine Bewertungen

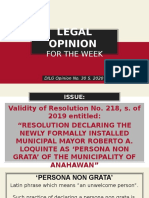

- Persona Non GrataDokument12 SeitenPersona Non GrataQhyle MiguelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Lady of Fatima University Valenzuela S.Y. 2020-2021Dokument2 SeitenOur Lady of Fatima University Valenzuela S.Y. 2020-2021Princess Jovelyn GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Lamut IfugaoDokument4 SeitenHistory of Lamut IfugaoLisa MarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Laws - Part 01 PDFDokument23 SeitenBusiness Laws - Part 01 PDFdarcyNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDAFDokument37 SeitenPDAFeinel dc100% (1)

- Identifying and Diagnosing Problems, The UN's Comparative AdvantageDokument1 SeiteIdentifying and Diagnosing Problems, The UN's Comparative Advantagevivian ternalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Filipino Martyrs (Published 1900)Dokument95 SeitenThe Filipino Martyrs (Published 1900)Bert M Drona100% (2)

- Public Info - FAKE NEWS - 17!10!04 (Reviewed)Dokument263 SeitenPublic Info - FAKE NEWS - 17!10!04 (Reviewed)Calvin Patrick DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fact Sheet On Villar ControversyDokument4 SeitenFact Sheet On Villar ControversyManuel L. Quezon III50% (4)

- Joseph Ejercito Estrada PDFDokument12 SeitenJoseph Ejercito Estrada PDFJealla May Mago TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax Churches DebateDokument19 SeitenTax Churches DebateAnonymous lTXTx1fNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument3 SeitenAnnotated BibliographyraojthsNoch keine Bewertungen

- STEPS Domestic Adoption AM 02 6 02 SCDokument5 SeitenSTEPS Domestic Adoption AM 02 6 02 SCobladi obladaNoch keine Bewertungen

- War On DrugsDokument5 SeitenWar On DrugsBE ALNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Divina PastoraDokument102 SeitenLa Divina PastoraAlvaro M VanEgas100% (1)

- Us Court of Appeals Upholds $354 Million Contempt Award Against Senator Marcos and Imelda MarcosDokument1 SeiteUs Court of Appeals Upholds $354 Million Contempt Award Against Senator Marcos and Imelda MarcosCocoLevyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Independence (Malolos Constitution) By: Ambrosio Rianzares BautistaDokument22 SeitenPhilippine Independence (Malolos Constitution) By: Ambrosio Rianzares BautistaMariah Ray RintNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mejoff Vs Director of PrisonsDokument2 SeitenMejoff Vs Director of PrisonsZMPonayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine Foreign Debt in Times of COVID-19: Choose From Among The Emoticons BelowDokument2 SeitenThe Philippine Foreign Debt in Times of COVID-19: Choose From Among The Emoticons BelowJames ReaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persons Deprived of Liberty A Human Rights Situationer (Hon. Jose Manuel S. Mamauag)Dokument8 SeitenPersons Deprived of Liberty A Human Rights Situationer (Hon. Jose Manuel S. Mamauag)Ham NesyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Indonesian Billionaires Behind TheDokument29 SeitenThe Indonesian Billionaires Behind TheKhristine ArellanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tyco PaperDokument27 SeitenTyco PaperSonia Dwi UtamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LESSON Owen J. Lynch, JR - Land Rights, Land Laws and Land Usurpation PDFDokument30 SeitenLESSON Owen J. Lynch, JR - Land Rights, Land Laws and Land Usurpation PDFLorraine DianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rules and Regulations Governing The Philippine Payment and Settlement System (Philpass)Dokument9 SeitenRules and Regulations Governing The Philippine Payment and Settlement System (Philpass)CPMMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 5 - Kartilya NG Katipunan (ReviewerDokument2 SeitenModule 5 - Kartilya NG Katipunan (ReviewerMj PamintuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine Press Under Martial Law - J. A. LentDokument12 SeitenThe Philippine Press Under Martial Law - J. A. LentliuggiuhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lcasean PaperDokument6 SeitenLcasean Paperkean ebeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tax Cases Nos 1-5Dokument68 SeitenTax Cases Nos 1-5Dimple VillaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1stnycm ResolutionsDokument4 Seiten1stnycm ResolutionspenstalkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Overview of Philippine Indigenous People's RightsDokument8 SeitenLegal Overview of Philippine Indigenous People's RightsJohn Michael BabasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurial StrategiesDokument4 SeitenEntrepreneurial StrategiesPattemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complaints and Grievances PolicyDokument8 SeitenComplaints and Grievances Policyairah jane jocsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Constitutions - Official Gazette of The Republic of The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenPhilippine Constitutions - Official Gazette of The Republic of The Philippinestweezy240% (1)

- Who Owns The Land and The Gold - The Tagean-Tallano Clan or God Thru The Filipino PeopleDokument17 SeitenWho Owns The Land and The Gold - The Tagean-Tallano Clan or God Thru The Filipino PeopleArnulfo Yu Laniba100% (3)

- Sochum Israel Position Paper, BRAINWIZ MUN Dhaka CouncilDokument2 SeitenSochum Israel Position Paper, BRAINWIZ MUN Dhaka CouncilLubzana AfrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rapport Philippines OBS15Dokument52 SeitenRapport Philippines OBS15FIDHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ibon Ccts Position Paper PaperDokument7 SeitenIbon Ccts Position Paper PaperJZ MigoNoch keine Bewertungen

- VP Poll Protest Fact Checks by VFFCDokument1 SeiteVP Poll Protest Fact Checks by VFFCVERA FilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Magellan's VoyageDokument19 SeitenMagellan's VoyageMar Roxas0% (1)

- Philippine ConstitutionDokument17 SeitenPhilippine ConstitutionKhim Ventosa-RectinNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Caricature Grievances Speech AquinoDokument39 SeitenA Caricature Grievances Speech AquinoJessa CañadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Marcos DynastyDokument19 SeitenThe Marcos DynastyRyan AntipordaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cavite Mutiny 1) Compare and Contrast The Accounts On Cavite Mutiny Using The Venn Diagram AboveDokument3 SeitenCavite Mutiny 1) Compare and Contrast The Accounts On Cavite Mutiny Using The Venn Diagram AboveRuth VargasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Development of Social Welfare in The PhilippinesDokument13 SeitenThe Development of Social Welfare in The Philippinespinakamamahal95% (20)

- Doh Historical BackgroundDokument3 SeitenDoh Historical Backgroundannyeong_123Noch keine Bewertungen

- IIEE Event On Dec 6 2014 at The Mills Country ClubDokument1 SeiteIIEE Event On Dec 6 2014 at The Mills Country Clubraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- K FactorDokument6 SeitenK Factorraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 - The Case of The Multimeter MeltdownDokument9 Seiten08 - The Case of The Multimeter Meltdownraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 - What Lies BeneathDokument15 Seiten02 - What Lies Beneathraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- TUP GRADUATE Admission FormDokument1 SeiteTUP GRADUATE Admission Formraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06 - The Case of The Floating NeutralDokument6 Seiten06 - The Case of The Floating Neutralraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAP Cowart NEDRIOverview 2004-07-12Dokument17 SeitenRAP Cowart NEDRIOverview 2004-07-12raul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2V - Light & Lighting FundamentalsDokument6 SeitenModule 2V - Light & Lighting Fundamentalsraul_bsu100% (1)

- Board of Electrical Engineering-Code of EthicDokument2 SeitenBoard of Electrical Engineering-Code of Ethicraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAP MODULE NO. 02B JamesShenot MeasuringAQImpactsofEEModule 2B Nescaum 2012-09-06Dokument50 SeitenRAP MODULE NO. 02B JamesShenot MeasuringAQImpactsofEEModule 2B Nescaum 2012-09-06raul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regulatory Assistance Project Electric Long-Range Planning SurveyDokument4 SeitenRegulatory Assistance Project Electric Long-Range Planning Surveyraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAP Schwartz Transmission EPAregionXworkshop 2012-4-24Dokument56 SeitenRAP Schwartz Transmission EPAregionXworkshop 2012-4-24raul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rap Linvill Euci 2014 May 13Dokument28 SeitenRap Linvill Euci 2014 May 13raul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAP Brown TransmissionPrimer 2004-04-20Dokument24 SeitenRAP Brown TransmissionPrimer 2004-04-20raul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio Management: Design Principles and StrategiesDokument8 SeitenPortfolio Management: Design Principles and Strategiesraul_bsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2 2023Dokument14 SeitenModule 2 2023ubpi eswlNoch keine Bewertungen

- COVID19 Management PlanDokument8 SeitenCOVID19 Management PlanwallyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asking Who Is On The TelephoneDokument5 SeitenAsking Who Is On The TelephoneSyaiful BahriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 Study GuideDokument3 SeitenChapter 6 Study GuidejoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EngDokument12 SeitenWHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EnghNoch keine Bewertungen

- RAN16.0 Optional Feature DescriptionDokument520 SeitenRAN16.0 Optional Feature DescriptionNargiz JolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mysteel IO Daily - 2Dokument6 SeitenMysteel IO Daily - 2ArvandMadan CoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. PinlacDokument7 SeitenPeople vs. PinlacGeenea VidalNoch keine Bewertungen

- A#2 8612 SehrishDokument16 SeitenA#2 8612 SehrishMehvish raniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes of Second English Language Panel Meeting 2023Dokument3 SeitenMinutes of Second English Language Panel Meeting 2023Irwandi Bin Othman100% (1)

- Statis Pro Park EffectsDokument4 SeitenStatis Pro Park EffectspeppylepepperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculam Vitae: Job ObjectiveDokument3 SeitenCurriculam Vitae: Job ObjectiveSarin SayalNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM in NestleDokument21 SeitenHRM in NestleKrishna Jakhetiya100% (1)

- Slavfile: in This IssueDokument34 SeitenSlavfile: in This IssueNora FavorovNoch keine Bewertungen

- WN On LTC Rules 2023 SBDokument4 SeitenWN On LTC Rules 2023 SBpankajpandey1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ulta Beauty Hiring AgeDokument3 SeitenUlta Beauty Hiring AgeShweta RachaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases in Political Law Review (2nd Batch)Dokument1 SeiteCases in Political Law Review (2nd Batch)Michael Angelo LabradorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Report On Salford Estates (No. 2) Limited V AltoMart LimitedDokument2 SeitenCase Report On Salford Estates (No. 2) Limited V AltoMart LimitedIqbal MohammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: WarningDokument3 SeitenAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: Warningمحمد کاشفNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Holy Rosary 2Dokument14 SeitenThe Holy Rosary 2Carmilita Mi AmoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Strategy: MarketingDokument14 SeitenRetail Strategy: MarketingANVESHI SHARMANoch keine Bewertungen

- Account Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceDokument4 SeitenAccount Number:: Rate: Date Prepared: RS-Residential ServiceAhsan ShabirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service ExcellenceDokument19 SeitenService ExcellenceAdipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authors & Abstract Guideline V-ASMIUA 2020Dokument8 SeitenAuthors & Abstract Guideline V-ASMIUA 2020tiopanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 504 Loan Refinancing ProgramDokument5 Seiten504 Loan Refinancing ProgramPropertywizzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023Dokument18 SeitenAdv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023senorislamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simple Yellow CartoonDokument1 SeiteSimple Yellow CartoonIdeza SabadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidDokument17 SeitenAlkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidZiauddeen Noor100% (1)

- The Overseas Chinese of South East Asia: Ian Rae and Morgen WitzelDokument178 SeitenThe Overseas Chinese of South East Asia: Ian Rae and Morgen WitzelShukwai ChristineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Management Plan GuidelinesDokument23 SeitenEnvironmental Management Plan GuidelinesMianNoch keine Bewertungen