Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Somali Famine Worsens Amid Signs of Plenty

Hochgeladen von

etimms5543Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Somali Famine Worsens Amid Signs of Plenty

Hochgeladen von

etimms5543Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Publication: THE DALLAS MORNING NEWS PubDate: 9/6/1992 Head: Somali famine worsens amid signs of plenty Officials

say 2 million facing death within weeks Byline: Ed Timms Credit: Staff Writer of The Dallas Morning News Section: NEWS Edition: HOME FINAL Page Number: 1A Word Count: 2097 Dateline: BAIDOA, Somalia BAIDOA, Somalia -- Dahaba Ali Aburahman stood on the dust-blown street, holding a 4-month-old baby near death. She offered her desiccated breast to the infant. Both mother and child remained hungry. Nearby strolled a youngster selling a tray of dates dipped in sugar. Mrs. Aburahman, a herdsmans wife, already has lost two of her five children to hunger. Like thousands of others, her family fled the barren countryside in search of food. She does not know whether her baby -- frail, barely the size of a newborn, and with sallow eyes -- will survive. God knows, she said. It is a horrifying scene made all the worse by its ordinariness. Death is taking about 200 Somalis a day in Baidoa, and despite the arrival of food donations, the toll is getting worse. Until now, relief teams trying to assess the catastrophe of Somalia have estimated that as many as 2,000 people a day are dying of starvation, and 1.5 million could die within weeks unless they get food. Now United Nations and Red Cross officials talk of 2 million Somalis facing death and an unknown number beyond that. They say each day brings news that adds to the scale of the tragedy. Refugees leaving remote villages to seek food aid in cities such as Baidoa, and assessment teams returning from areas previously unseen by relief agencies, say starvation in Somalia may be more widespread than ever imagined. Its the tip of the iceberg, said Mohamed Sahnoun, the U.N. special representative for Somalia.

Surreal existence Somalia presents a surrealistic world where mass starvation and sugared-date sales boys walk the same streets, where drought and war and disease afflict hundreds of thousands while gunmen and greedy merchants get rich. A global relief effort -- outgunned and overwhelmed -- has just begun to reach across the country. As word spreads that food is coming, villagers who had been sitting inside their huts waiting to die move on bone-thin legs toward Baidoa and other feeding centers. Were not stopping starvation; were only slowing it, said Dr. Said Muse Aden, who heads the UNICEF office in Baidoa. The exodus from the countryside grows at a time when new crops need to be planted to break the cycle of famine. Somalias war and famine emptied Baidoa of its original residents. Farmers and nomads came in from the countryside to take their place. Since the beginning of June, one relief official estimated, the population may have more than doubled. Relief agencies now guess that as many as 100,000 people are living in Baidoa. Some of the hundreds of Somalis who die each day collapse just outside relief kitchens that offer a chance for survival. Several miles to the north of Baidoa, a village chieftain set aside his sword and hand grenade, his protection against bandits, to cleanse himself in preparation for prayer. He stood next to a shallow open grave that had been scratched into a barren cornfield with arrows and sticks. For days, starving Somalis had walked past the body of a young boy who fell beside the dirt road leading to Baidoa. Village chieftain Sheik Caliyoow Sheik Ibrahin stopped to bury the boy in accordance with Islamic custom. Afterward, Sheik Caliyoow, 56, the father of 15 children, picked up his weapons and began walking toward Baidoa with his ailing wife to seek medical help for her and more food for his village of Goof-gadut. Relief workers have begun providing some food to Goof-gadut, but Sheik Caliyoow said his village doesnt have enough food or water. His people dont like the limited supplies of rice that have been taken

there because they dont feel well after eating it. They want sorghum instead. Dr. Aden supports the idea of distributing sorghum instead of rice. In addition to the local populations preference for sorghum, he said, it is a less attractive target for looting than rice, which is widely consumed elsewhere. Sheik Caliyoow planned to make a direct appeal to relief agencies in Baidoa. We dont need speeches, we need more food, he said. There are no seeds In an effort to stop the migration of rural people to Baidoa, the International Committee of the Red Cross is staffing relief kitchens in more remote areas. It operates 22 kitchens in Baidoa and more than 40 in the surrounding countryside. A rainy season is approaching in about a month, and a Somali agronomist said that seeds must be planted within weeks. But there is little seed available in the Baidoa farming region, where empty villages -- and untilled fields cracked like a jigsaw puzzle by drought -- are all too common. A few miles from the roadside burial is a village of thatch huts known as Haawen. Its chief, Hassan Abukar Ibrahim, 48, said his village once had herds of camels and other livestock too many to count -- that were all stolen by troops loyal to deposed Somali dictator Mohammed Siad Barre. We are ready to plant, he said. But there are no seeds. Until recently, the villages population was dispersed more deeply into the countryside. A relief worker who passed through Haawen about a week ago counted 14 people there. Now, several hundred wait for food. The Red Cross set up a kitchen last week that quickly ran out of food when hundreds of hungry people began showing up. A feeding center established by Concern, an Irish group that focuses on saving malnourished children, continues to operate in Haawen and on Tuesday fed more than 1,800.

Before the kitchen opened, Mr. Ibrahim said, the villagers ate grass and leaves. People began to return, he said, when word spread that food was there. He is worried that the Red Cross kitchen has no more food. Hundreds of villagers, mostly women holding empty pots or bowls, squat patiently by the roadside hoping that a truck with food will arrive. Mr. Ibrahim believes that there will be an end to the problems of Somalia only when there is enough food. I am thinking with my stomach now, said the father of seven. Struggle to plant Paul Oberson, a delegate to the International Committee of the Red Cross in Baidoa, said Somalias ultimate recovery depends on re-establishing agriculture. But, he said, farmers must first be nourished enough to work their land. Then, they must have enough dry food to feed their family until the harvest, so they dont eat the seed or the crop before it matures. An assessment in July revealed that some corn actually was being grown and harvested in some pockets in southeastern Somalia, said Dr. Tibebu Haile Selassie, UNICEF program coordinator for Somalia. One program, he said, hopes to collect 500 tons of seed from local harvests to help re-establish 15,000 families in the lower Juba and lower Shabele valleys if we are quick enough to buy and distribute it. There is seed available immediately if we are quick enough to stop them eating it, he said. Dr. Selassie said the program would not help farmers in other regions, including the Baidoa area. We have to start somewhere, he said. A slow start Relief efforts have faced numerous problems throughout southern Somalia. Some of the relief agencies involved, particularly those of the

United Nations, have been criticized for not responding quickly enough to the crisis and for allowing bureaucratic restrictions to interfere. Dr. Aden, the UNICEF representative in Baidoa, said the United Nations decision to pull out of Somalia in early 1991, as the country plunged deeper into armed chaos, was really a big mistake. We should have a stronger presence, the Somali physician said. I am not happy -- not only with the United Nations . . . but with the whole international community that has not reacted soon enough. In Baidoa, he noted, myself and a logistical assistant . . . are the U.N. presence here. Dr. Selassie, however, said he would like to discourage more than what we have in Baidoa. We dont need a big presence, he said. There are so many areas that have no services at all. At the Baidoa hospital, there is no electricity and no water to sterilize instruments. The doctors and nurses have even run out of gauze. Scores of donkey carts, as well as a few tanker trucks, line up at the single well that provides water for Baidoa. Local relief officials say the water is often gone by early afternoon. A modern water supply system built by the Chinese and a Finnish-built electrical grid for Baidoa were looted or destroyed. Dr. Aden said efforts are being made to dig another well, but so far, they have been unsuccessful. Stalled by looters One of the most serious obstacles for relief efforts is the difficulty of moving supplies. The bulk of Baidoas relief supplies, as is the case in most inland areas, is brought in by airlift. On Saturday, U.S. Air Force cargo planes joined that airlift and began delivering aid to Baidoa. Civil unrest and armed bandits prevent relief groups from distributing food throughout the country in truck convoys that can transport much greater quantities. Gangs of gunmen exact fees from relief agencies for bringing in supplies of food by ship or plane.

Many relief trucks have been attacked even as they were leaving the port of Mogadishu. This month, the United Nations is scheduled to bring in armed troops to provide security for relief supplies. But some relief officials are concerned that the U.N. troops may escalate the violence in Somalia. Whats going to happen if you have hundreds of (Somali) guards out of work? asked Stephen Tomlin, country director for the International Medical Corps in Somalia. You will have some very unhappy and heavily armed people. A kind of balance Mr. Oberson of the Red Cross said relief workers have found ways to work with Somali clans, using Somali guards to protect supplies. There is a kind of balance here, he said. One suggestion, which has the support of some relief officials as well as officials who are part of one of the largest of Somalias warring armies, is to re-establish Somalias police force, whose numbers include different clans. Even without food being shipped overland, large amounts of the supplies brought in by air never reach those in need because of pilfering and armed looting. Baidoa, for example, has a flourishing market where relief supplies are sold with impunity. Near the citys largest mosque, merchants sell rice, beans and flour from 50-kilogram bags clearly marked as relief supplies. Packages of high-protein biscuits, also relief supplies, are a common item. Only a few merchants make any attempt to cover up the markings. Supplies lacking at the hospital can be bought in stalls at the market. Perhaps not coincidentally, the hospitals pharmacy was looted about two weeks ago. Its remarkable that we cant get a convoy in, but the black market traffic goes almost anywhere, one relief worker in Baidoa said.

Col. Yusuf Sharif Nur, governor of Baidoa, said that the primary problem is not looting but rather not enough food. He also complained that the International Committee of the Red Cross distributes where they want, including to people who are not sympathetic or are enemies of the United Somali Congress, the faction that holds sway in Baidoa. He said the congress could do a better job of distribution. Available at a price It is apparent that some food outside the relief network, as well as other supplies, is being distributed. Fresh beef and goat is readily available from several stalls, as are grapefruit, limes, fresh beans and tomatoes. The market offers souvenirs, laundry detergent, shower thongs and a hundred other commodities. The Bikiin Baar & Restaurant serves spaghetti with camel meat, as well as assorted dishes. Patrons can be seated inside or at tables with umbrellas on the patio, which offers a limited view of the pathos on the street, where the starving sleep in the dirt or beg. When one Westerner tried to offer her unfinished spaghetti to a hungry child hovering outside, the patio was suddenly invaded by dozens of youngsters. The restaurants owner cleared the crowd by menacing an AK-47 assault rifle. One boy was knocked down in the rush to safety. Weakened by hunger, he had difficulty rising to his feet. The sound of the restaurant owner pulling back the bolt of the AK-47 brought the boy up, and he staggered away.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- False Accusations Can Wreak DisasterDokument4 SeitenFalse Accusations Can Wreak Disasteretimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- State of Alert: Many LA Residents Fear Repeat of 1992 Violence As Scars From Riot RemainDokument5 SeitenState of Alert: Many LA Residents Fear Repeat of 1992 Violence As Scars From Riot Remainetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- DMN Nctrca Ag Letter 8-5-13Dokument5 SeitenDMN Nctrca Ag Letter 8-5-13etimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2-Sample TPIA LetterDokument2 Seiten2-Sample TPIA Letteretimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Amended Cost Complaint 5-28-14Dokument2 SeitenAmended Cost Complaint 5-28-14etimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCTRCA Coverage PDFDokument30 SeitenNCTRCA Coverage PDFetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- False Accusations Can Wreak DisasterDokument4 SeitenFalse Accusations Can Wreak Disasteretimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4-NCTRCA Cost ComplaintDokument25 Seiten4-NCTRCA Cost Complaintetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 6-Dmn Ag Letter Dart 11-14-2013Dokument3 Seiten6-Dmn Ag Letter Dart 11-14-2013etimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2-Sample TPIA LetterDokument2 Seiten2-Sample TPIA Letteretimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Court Structure ChartDokument1 SeiteCourt Structure Chartetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4-NCTRCA Cost ComplaintDokument25 Seiten4-NCTRCA Cost Complaintetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7-Abbott Open Records Letter Ruling OR2012Dokument7 Seiten7-Abbott Open Records Letter Ruling OR2012etimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- TPIA DeadlinesDokument2 SeitenTPIA Deadlinesetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Whistle-Blowers Say Military Waging Psychological WarfareDokument9 SeitenWhistle-Blowers Say Military Waging Psychological Warfareetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- 3-TPIA FormDokument1 Seite3-TPIA Formetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- NC Tent Plus SuppDokument32 SeitenNC Tent Plus Suppetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCTLETTERDokument2 SeitenNCTLETTERetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Columbia Wing Tiles Possible CulpritDokument6 SeitenColumbia Wing Tiles Possible Culpritetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- TPIA DeadlinesDokument2 SeitenTPIA Deadlinesetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- DEA Breaks Up North Korean Meth RingDokument4 SeitenDEA Breaks Up North Korean Meth Ringetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Under The GunDokument6 SeitenUnder The Gunetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cycle of Drought and Famine and DeathDokument7 SeitenCycle of Drought and Famine and Deathetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Terrorism Cases Highlight Flaws in Visa SystemDokument2 SeitenTerrorism Cases Highlight Flaws in Visa Systemetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grenades Now CommonDokument3 SeitenGrenades Now Commonetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Black Market Nuclear Deals The Stuff of NightmaresDokument6 SeitenBlack Market Nuclear Deals The Stuff of Nightmaresetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- How Far Is Too Far in War On TerrorDokument3 SeitenHow Far Is Too Far in War On Terroretimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arkansas Guardsmen Feel One Another's PainDokument3 SeitenArkansas Guardsmen Feel One Another's Painetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- Filipino Women in Kuwait Target of AttacksDokument4 SeitenFilipino Women in Kuwait Target of Attacksetimms5543Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 20 RevlonDokument13 Seiten20 RevlonmskrierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baobabs of The World Cover - For Print PDFDokument1 SeiteBaobabs of The World Cover - For Print PDFBelinda van der MerweNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calcium Cyanide: Hydrogen Cyanide. CONSULT THE NEW JERSEYDokument6 SeitenCalcium Cyanide: Hydrogen Cyanide. CONSULT THE NEW JERSEYbacabacabacaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Psychology (2022)Dokument642 SeitenIntroduction To Psychology (2022)hongnhung.tgdd2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mycesmm2 Quiz: Please Circle Your Answer! Time Allocated To Answer Is 30 MinutesDokument2 SeitenMycesmm2 Quiz: Please Circle Your Answer! Time Allocated To Answer Is 30 MinutesSi Qian LuiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutorial 2 Organizing DataDokument2 SeitenTutorial 2 Organizing Datazurila zakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model CV QLDokument6 SeitenModel CV QLMircea GiugleaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geared Motor Device 100/130V E1/6-T8Dokument2 SeitenGeared Motor Device 100/130V E1/6-T8seetharaman K SNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 F 957375 B 361250 FB 704Dokument15 Seiten9 F 957375 B 361250 FB 704api-498018677Noch keine Bewertungen

- RNA and Protein Synthesis Problem SetDokument6 SeitenRNA and Protein Synthesis Problem Setpalms thatshatterNoch keine Bewertungen

- MahuaDokument12 SeitenMahuaVinay ChhalotreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industrialisation by InvitationDokument10 SeitenIndustrialisation by InvitationkimberlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nurs 512 Andersen Behavioral TheoryDokument7 SeitenNurs 512 Andersen Behavioral Theoryapi-251235373Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter1-The Clinical LabDokument24 SeitenChapter1-The Clinical LabNawra AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages PVT LTD B-91 Mayapuri Industrial Area Phase-I New DelhiDokument2 SeitenHindustan Coca-Cola Beverages PVT LTD B-91 Mayapuri Industrial Area Phase-I New DelhiUtkarsh KadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. Leadership/ Potential and Accomplishments Criteria A. InnovationsDokument5 SeitenI. Leadership/ Potential and Accomplishments Criteria A. InnovationsDEXTER LLOYD CATIAG100% (1)

- Electrosurgery: The Compact Electrosurgical Unit With High CapacityDokument6 SeitenElectrosurgery: The Compact Electrosurgical Unit With High CapacityPepoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiment-3: Study of Microstructure and Hardness Profile of Mild Steel Bar During Hot Rolling (Interrupted) 1. AIMDokument5 SeitenExperiment-3: Study of Microstructure and Hardness Profile of Mild Steel Bar During Hot Rolling (Interrupted) 1. AIMSudhakar LavuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kim Lighting Landscape Lighting Catalog 1988Dokument28 SeitenKim Lighting Landscape Lighting Catalog 1988Alan MastersNoch keine Bewertungen

- TympanometerDokument12 SeitenTympanometerAli ImranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceramic Fiber 23Dokument28 SeitenCeramic Fiber 23Kowsik RajendranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parreira CVDokument8 SeitenParreira CVapi-595476865Noch keine Bewertungen

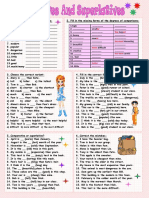

- Comparatives and SuperlativesDokument2 SeitenComparatives and Superlativesjcarlosgf60% (5)

- Material Safety Data Sheet Glyphosate 5.4Dokument5 SeitenMaterial Safety Data Sheet Glyphosate 5.4Ahfi Rizqi FajrinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forensic Toxicology: A. Classify Toxins and Their Effects On The BodyDokument28 SeitenForensic Toxicology: A. Classify Toxins and Their Effects On The BodySajid RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Itopride HCL Pynetic 50mg TabDokument2 SeitenItopride HCL Pynetic 50mg TabAusaf AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- PROD - Section 1 PDFDokument1 SeitePROD - Section 1 PDFsupportLSMNoch keine Bewertungen

- CoasteeringDokument1 SeiteCoasteeringIrishwavesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steri - Cycle I 160 New GenDokument16 SeitenSteri - Cycle I 160 New GenLEO AROKYA DASSNoch keine Bewertungen

- DR - Vyshnavi Ts ResumeDokument2 SeitenDR - Vyshnavi Ts ResumeSuraj SingriNoch keine Bewertungen