Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Igba Sango

Hochgeladen von

siddharthasgieseOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Igba Sango

Hochgeladen von

siddharthasgieseCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Symbolism and Ritual Context of the Yoruba Laba Shango Author(s): Joan Wescott and Peter Morton-Williams

Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 92, No. 1 (Jan. - Jun., 1962), pp. 23-37 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2844319 . Accessed: 27/09/2013 09:15

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Symbolism and RitualContext oftheYoruba Laba Shango

JOAN WESCOTT & PETER MORTON-WILLIAMS

symbols or sym-

bolic acts which,withintheirculture,existwithouta sanctioningexplanation. He must consequently decipher and explain discursivelywhat the native intuitivelyperceives and responds to. In seeking to discover what significance such a symbol has, we must findfirst how the formis set in its institutional context; and second, how it is integrated into the religious,moral, and motivational systems within the society. In this analysis we have interpreted a symbolforwhich the Yoruba can offer no explanation; we have therefore tried to introduce the Yoruba consciousnessmuch as Griaule did with the Dogon culture, and Evans-Pritchardwith those of the Azande and Nuer. In a purely structural-functional typeofanalysisinterpretation is, in contrast, limitedby such direct references as can be made to the model; therethe anthropologist too oftenassumes that the symbolcan simplybe interpreted reductivelyas having referents in his constructed patternofsocial relations.In thiselucidation ofa complex non-verbalsymbol,our interpretationsexplore a wider range of meaning,but theseinterpretations nevertheless may be referred to evidence that can be judged by objective criteria.Weight is added to our interpretation of the symbol under discussion by showing that its elements are given explicitmeaningin othercontextssuch as myths, praise songs,and ritualsculpture. The symbolthat concernsus here (Plates I and II) is one which decorates the laba, a flat red leather bag about twentyinches square which is part of the equipment of everypriestof Shango, the thundergod of the Yoruba of south-west Nigeria.' Covering the face of the laba are the fouridentical symbolic panel designs forwhich we could elicitno verbal explanation. The bag itself is used to contain ritualobjects,and is carried a spot where lightninghas struckand, also, when in full by the priestswhen purifying panoply theyjoin the processionof the priesthoodat the main annual rite of the god.2 For the Shango devotees,the bag has symbolicvalue, and it seemsfromdiscussionswith them that its significancelies mostlyin its decorated panels. But theirmeaning is not were only able to describeits use; they perceivedin rational terms,and the worshippers could not interpretthe decoration as a whole or by parts in termsof any of their exare particularlyaverseto intellectualapproaches planatorysystems. Shango worshippers and theirritual symbolicforms often are preservedwithoutexplanation and even without a mythsupporting theirmeaning. We are here attemptingto discover by conceptual and aesthetic analysis what the The analysisis to be founded panel design directlyconveysto the Yoruba as a symboJ. the on in the ritesof Shango, and on the the of its aesthetic content upon laba, place of to those when found elsewherein Yoruba resemblance its decorative elements that,

23

THE ETHNOGRAPHER HAS OFTEN TO FACE THE PROBLEM of interpreting

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

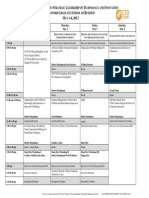

and religious religion art,have explanations of a kindwe can interpret satisfactorily. we shallrelatetheconfiguration formed Concluding, by thecombination ofstructural elements to theritualuse ofthebag. As we shallshow,thismethod and decorative can be appliedjust as rigorously of history and structural-functionalism; as the methods ofYoruba symbols prolonged study and oftheir functioning in theirculture has convincedus thatto understand themand to convey theunderlying religious conceptions, thesetwo analytic techniques mustbe supplemented. But before we can go on to the analysis, we shallhavetosetforth theethnography ofthelabain somedetail. Whilewe werein theYoruba metropolis theHigh Priest ofthe Oyo, we persuaded Shangocult(theMagba) toallowustohavea labamade.It isnowintheBritish Museum. The laba,made up ofgoatskin dyedin traditional red,consists ofa pouch,a flapthat hangsovertheopening ofthepouchcovering itsfront, and a longstrapwhichenables thelaba to be worndownone side ofthebodywhilethestrappassesovertheopposite shoulder. Along the bottomedge of the flap are seventassels, each a triangle with bundles ofleather strips hanging from thenarrow them. Exceptfor vertical design often seen along each side of the front face of the pouch,only the flapis decorated.The elements ofthedecoration arefour intricate panelson a ground ofredcloth.Each ofthe four panelscarries thesamedesign, and it is substantially thesameon every laba made in Oyo.3 Not onlytheMagba and histwodeputies, but otherShangopriests and wor;4 and it is this shippers as well, have asserted that everylaba mustbear thisdesign design, traditionally repeated in each ofthefour panels,thatcontains theritualmeaningofthelabaand hasprovoked thewriting ofthis paper. The paneldesign itself, together with itsborder, is nmade up ofcut-out yellow leather, embroidered withnarrow strips ofblack and whiteleather, and is stitched overa red felt background. Four irregularly shapedgreenleather piecesmarkthecorners as part ofthebackground for thecentral yellow motif; twoleather shapesinterrupt theredfelt theyellow background forming a diagonalofblackbehind design5 (Fig. opp. PlateI). Decoratedleather work is a longestablished craft in Oyo,and,likemost crafts there, it is confined to certain lineages. ofto-dayare members ofone or The leather workers other ofthree lineagegroups thatare segments ofa lineageformerly in Old Oyo. Only one of thesesegments, the Otun 'the right(hand groupof) leather Shona,6 literally, oftheMagba. The memworkers,' is authorized tomakelaba,and then, onlytotheorder bersofthis oflabaas so important a taskthat themaking itis closely lineagegroup regard and senior supervised and in partdone byonlythemost members skilled amongthem. A newly it is delivered to theMagba, thetwofacesofthe made labais sealedbefore pocketbeinggluedtogether to open withstarch paste.The Magba alone is permitted it,and theunsealing is donein secret in theprivacy ofhisshrine. Whileopening theone we commissioned, he worked ofwater, intothesealed leathera solution palmoil,and somemagicblackpowder, that ofwhichthecomposition was notdisclosed. He asserted the leatherwould tear if anyoneelse attempted to unseal the bag, or if he himself neglected to use thepowder.When theoutsideof thepockethad been saturated and softened by the mixture, he worked thesolution intothepocket, gradually separating thefaces.The operation abouttwenty and causing was an arduousone,taking minutes him to sweatprofusely. thatits is so rarely ofa highpriest exertion Physical required herepoints oftheoperation.7 occurrence totheritual importance

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

25

As a signofacceptance intotheShangocult,a newpriest to have hisown is required laba made. But he does not deal directly withthe makers, as he does withthewoodcarvers whenhe needsa dance staff. The Magba mustcommission it forhim,and receivepayment on behalf ofthecraftsmen. to obtain Whileevery newpriest is expected his first laba in thisway, some may laterpurchaseothers to displayin theirshrines. Thesesupernumerary onesneednotbe opened. Thelabais wornwhenthepriest travels in hisvestments to officiate at someriteaway from hisshrine. It is never wornwhilethepriest is in a stateofpossession, whenhe then is dressedas the god. When theyare not carried,laba hang in the domestic shrines (gbongon) oftheShangopriests (Plate II A) and are usedto contain only'thunderbolts' (edun ara),8i.e. neolithic celts,and the sacredgourdrattles(shere), whichare shaken whileprayers are addressed to Shango. They are neverused to carrythe double-axe dancestaffs (oshe), which are usedonlyin a state ofpossession.9 The Shangocult,compared withother Yoruba cults, is remarkable for itselaborate ritual, and theabundanceand variety ofitssculpture and symbols. Yet itsbodyofmyth concerning theritualobjectsis particularly meagre.The myths are,forthemostpart, confined to stories of Shango and are concerned withhis lifeas a king,his death and re-emergence as a god,and hisrelations withother godsand withmankind.10 It appears thatin so restricting the subjectmatter of his myths, the Shango worshipper ensures that when, he contemplates his ritualobject,the rationalfunctions of his mind are silenced;as fully as he may he openshimself to emotions liberated by the visualand intuitive experience ofthese forms. Thusitseems tous thathe is consistent in demanding thatthemystery surrounding hisritualobjectsbe preserved so thathe mayrespond to themfully on an emotional level; an explanation wouldlimitor vitiate their evocative poweras symbols. It is especially to be notedthatneither of the two mostimportant symbolic objectsin the Shango cult-the thunder-axe (oshe)and the laba-are given anyexplanation. The former is carried during theviolent, frenzied possession, thelatter on ritually sanctioned plundering The violence of the typicalShango expeditions. possession and the plundering of the priests are bothin conflict withnormalYoruba rulesofbehaviour described and moralattitudes; and they are neither ofthemdirectly in the myths and praise songs,whichascribeviolenceonly to Shango,neverto his devotees. Sincethedevotees do notadmittheir anti-social propensities, thetwoobjects which are associated withthem areperhaps notexplained. for thisadditional reason Amongthosemostactivein thecult,twopolar types one is maybe distinguished: hearty, givento noisy displayand fascinated by conjuring; theother is lessconfidently boisterous and often temperamental. Bothtypes are subject to violent boutsofdissociationor possession, and are transvestite in this state. Unbridled emotions areon thewhole shownonlyby thepriests and ofthoseYoruba cultsthatrecognize ofpossession; states among these,Shango possessions are by far the mostfrequent. Althoughviolence, are generally speaking, is not a Yoruba trait,Shango and his possessed worshippers to be violent. known Theircharacteristic responses are irrational, thatis, they respond to objects and form imagesand ideas by direct unconscious and production, perception without the mediationof reflective the thought or ethicalconsiderations. Although conform worshippers to theconventions violenceand ofYoruba behaviour in avoiding destructiveness of exceptin possession, there is good evidencethattheyhave fantasies

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

-4

4''

COLOUR Background Black

KEY

White

Black

Yellow

Green

Red

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOANWESCOTT & PETER MORTON-WILLIAMS

The Yoruba Laba Shango

PLATE I

*~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.. ZiS~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.. . ........

.. .... ..,.

...

... ......

Sti,.t

':J:';;:g:':'~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ r'X MEl':

*M U 'LWIi~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-s '

2S

11||&''S

|S:

K~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0.

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

& PETERMORTON-WILLIAMS WESCOTT JOAN

a | |

1t1 t t | | | ! ! | [

_ _ l _ I,f2s .' . ..

|

The Yoruba Laba Shango

PLATE11

_sn

___-. _ii__

tiE1L

__' 1

-'st;'i _ 0 .>, eit

l f .i'4 _

-M

_l-;1X#l

.'

_}t-_

_'_ _

.7.|_.

_'

_-t.

_21

Z

._

#

qF

.,4,:62

,'.

*i __

'

i.

..

_..n..

,,

E.,!__iX';

:.

:'' '

'

, .:':'w';

:_

"

tC;-! sO * -jE;'-.S. 1., a i r

Rts g

* it

w

.

.'.W8t...

.

,.:-

..... . ;

. .

..

-

...........

j iM ..........

E

t;i?'

*&

Set

jtP

-;x3S_|s2W@>

> t.,A. . W < W .

<'

F A:

t_

4;s o * * ' W . Q) *i ; ' .6_ i. . W i *

@;'Ssi*?>e

IX

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOAN WESCOTT & PETER MORTON-WILLIAMS

The Yoruba Laba Shango

PLATEI]

_g_~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0

~~~~~~~~~~A

'

S.~~~~~~~~

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

& PETERMORTON-WILLIAMS The Yoruba Laba Shango WESCOTT JOAN

.-' |*

PLATEIV

. #s_

Ww l

_R

'

s l

1! __

-1

[i L.s. |

|

| l_

|-|

! | __

_

_!

1 | II s_ -s_ a _S - W_ *.X ZllPR FB

_ _ _ 2

|_ |

r

__ X a S MG

_

r

_ w_ E

...

,

_ _ _

E

* | | I ,| I

.

_ _

l | l

. _ E .Ii _

_

_w_

,I _ _ _ _ |

E ,

sB

@ F. l ......

_,_ |

z |

;. :.:.:

_._

..

_ _ ...

|

|

sw

__

B -

li

i

ar: -

. . 7,1t,b,.

*: Wa:::

:B:' s:

- -

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

27

themand attribute to themselves the magicalcontrol ofthedestructive force oflightcheerful in the ning.We havehearda possession priest (hisdemeanour enough)saying, presence ofa Moslemwithwhomhe was on friendly thathe wouldmurder terms, any of his who wantedto marrya Moslem; and we have also knownShango daughter in undercover priests who believedtheyhad used lightning in magicalwarfare feuds amongthemselves. The cult of Shango,as distinguished from his privateworship, is established only in those Yoruba areasthatwereundertheimperial itscollapsein the ruleofOyo before nineteenth century. The culthas centralized theoccupancy ofsomeofits organization, highest priestly offices beingconfined tomembers ofcertain The rest Oyo lineages. ofthe priesthood, whether in Oyo orin theprovinces, is recruited from locally mendiscovered tobe subject tostates ofpossession byShango. Devoteesmay be bornintothe cult,or assigned to the worship of Shango by Ifa, theYorubagodofdivination. Whenan individual is a member ofa cultfrom childhood, he musttakepartin rites addressed to thegod throughout hislife.But shouldthecult failto satisfy the needsof his personality, will occur.Then, symptoms of disturbance through themediation ofIfa,he mayfind cultwhere hispersonality hiswayintoanother matches that ofthe god,andcan be defined, canalized, andfulfilled bycultmembership." Novicesto the priesthood of Shango are selectedand partlytrainedby the local associations of Shango priests, but each one musttravelto Oyo, accompaniedby a priest as sponsor, to receiveconfirmation in his callingand finalinstruction from the Magba. As priest,he is entitledelegun, means 'one who which literally translated becomes must ridden', thatis,possessed selected nowhave by Shango.The newly priest hisfirst labamade. The laba servesboth symbolic and utilitarian endsin cultritual.But sinceitssize is largerthan thatdemandedby its contents, we relatethisto its importance rather thanitsuse. It is wornwhenthepriest travels in hisvestments in somerite to officiate away from hisshrine, particularly to placeswherelightning has struck. His taskthere is to find and 'digfrom theearth'"2 thethunderbolt thatdogmadeclares Shangohurled, thento announcewhatsinsShangopunishes by thatact and whatsacrifices thosewho live theremustoffer in expiation.On thisand otheroccasionswhen Shango makes visible hispowerand anger, andworn down thelabais carried outside theshrine hanging the leftside of the officiant and diagonally withthe strapover his oppositeshoulder across hischest(PlateII B). For reasons whichare beyondthe scope of thispaper to elaboratefully(MortonWilliamsI960), theleft sideis ofritualsignificance to theYoruba;13 and thediagonal line described by the strapacrossthe chestis, as we shall see by its repetition in the panel designand in therestatement consistent ofits meaning in other ways,a suitably and not merely an from convenient means of wearingthe laba. It may be inferred aesthetic consideration ofYoruba artthatthere, as inWestern culture, thediagonalline might be an expression ofenergy, in tension, and irrationality.14 The left sideindicates the generally acceptedsensethesecondary and the and rejected contents ofa culture repressed contents ofthe unconscious. Confining ourselves to thespecific context ofthe Shangocult,someoftheevidence for thisgeneralization maybe cited;one ofShango's praisesongs includes thefollowing words:

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

I want to hail Shango; He helped me to rebuild myhusband's house ... He shoutedin the rooflike a spirit; He used his lefthand to carryhis laba. The song,sung by women devotees,tellshow Shango strucka house withlightning, and in so doing filledthe laba of the priestwith the victimizedhouseholder'swealth which was thenused to rebuild the priest'sshrine. Another instance of the symbolic use of the lefthand and its association with the unconscious is important.At a point in the trainingof a possessionpriest,the Magba places his lefthand on the initiate'shead and recitesthe praise names ofShango. During this recitation,the god reveals to the initiate the specifictaboo that will prevent his being sent into possession at inappropriate moments. Moreover, it is a peculiarityof possessionprieststhat Shango appears to them and speaks to themin theirdreams. The Magba of the royal shrine at Koso includes in his morningrecital of Shango's praise names the words, 'the dream is fatherof the god.' Since it has been established by that personages in dreams are manifestations of psychic complexes, it is psychologists clear that the deity Shango corresponds to some extent to unconscious complexes typical of his worshippers.Thus the impulses to violence and caprice that make up the complex typical of Shango worshippersare illustratedsymbolicallyon the laba panel; and the wearing of the laba on the leftside may be directlyconsistent with the factthat these impulses,appropriate to Shango, findsafe expressionin his cult, though they are not accepted by the Yoruba generally. This psychic complex occurring in the perof the devotees can only be acknowledged when projected on to the sonalitystructure When with the god, god Shango. Shango priestsin a state of possessionare identified are dominated they by an otherwise repressed need to vent their aggressive and exhibit his wild frightening impulses. The devotee in possessionmay withoutrestraint emotionsin uninhibiteddisplays of power and passion, disregardingthe rigid code of it is plausible to infer Yoruba social etiquette.Beyond its necessityas insignia of office, with the leftside illuminatesan aspect of the god that the association of a cult artifact and linksit with the personalitycomplex forwhich it is an appropriate symbol. In this on theirexpeditions connexionit is evidentwhy the laba mustbe worn by Shango priests theirlove of destructivepower by to houses struckby lightning,for there they satisfy exploiting an already calamitous situation. Here is, in fact,an example of a type of anti-socialbehaviour which has been sociallysanctioned. The rigidlystandardized design on the panels of the laba is of considerable signifiattribute a numinousquality cance in the imageryofthe Shango cult,and Shango priests to it. Moreover, the design contrastsremarkablywith the relativenaturalismand symmetryof the bulk of Yoruba plastic art and is, as far as we know, the freest expression drawfifromtheirrealm of myth.'5Since it is so veryfarfromotherYoruba conventions, it is particularly tantalizingthatthe Yoruba seem to have no explanation ofits meaning. We have questioned more than thirty priestsin different partsofYorubaland including the Magba of Oyo and two of his deputies, and also the Magba of the king's own Shango shrine there. We also inquired among the senior members of the OtunShona lineage group who made the laba. None of them could explain the design or contribute

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

29

a mythabout it or about theintroduction ofthe use ofthe laba, althoughover some years rapport was closely established with most of the priestsconsulted, including the late Magba. When the Yoruba are unwillingto disclose a myththeywill as a rule eithersay so or fabricatean alternative;theywill seldom deny its existence. On first examiningthe panel, the design may appear (as it has to many Europeans) to be a variation on a swastika. If we have supplementedwhat is presentin the form through anticipating a swastika by virtue of our knowledge of it in other culturesparticularly as a form of Jupiter's lightning in Graeco-Roman iconography,16 it is ofa stylizedlightning none the less strongly flash.Since the priestofthe thunsuggestive has struck, it is fitting der god carriesthe laba to places where lightning that thisdesign be a graphic and explicit indication of function.But many elementsin both the form and colour of the panel design lead beyond this firstassociation with a swastika as a stylizedlightning flash. in Yoruba art There is a strongand ever-present tendency to anthropomorphism and religiousimagery,and thisdesign,whetheror not it is derived froma swastika,has Here the patterntakes the formof a dancer; and apparentlybeen anthropomorphized. the head-dress,the dance position,and the emblematicblack, white,and yellow colours of the figurelead us to postulate that this dancing figureis a representation of Eshu (Elegbara) the Yoruba trickster god.'7 The head-dress (in the upper right corner of the panel) resembles that worn by Eshu priests,although it is oversize,just as it is on the carvingsforEshu where thisdismark is exaggerated for emphasis (Plate III). The dance position-upper tinguishing arms level with the shoulders,forearms in opposite directions(the rightraised and the leftone pointingdownward18)and the open postureofthe legs-is like the mostdistinctive of the movementsin the Eshu devotees' ritual dance (Plate IV A). Energetic and sensual, the dance forEshu is unmistakableand stands in contrastto the tightness and of movements in mostotherYoruba ritual dances, including thoseforShango. restraint Lines that mightbe consideredin excess of the dancing figurecontributeto the impression of movementand speed. In his myths,Eshu as the trickster and god of mischief is at once. His songs and praise names tell of the never in any one place, but is everywhere dazzling speed with which he travelsand of his agilityas a dancer. Although the horizontal lozenge-shapedhead is balanced by the verticallozenge of the torso,the less restfulverticaland diagonal lines dominate. The tensionin theselines and in the asymmetry of the design gives an impressionof chaotic disorder (a situationwhich Eshu delightsin creating),and the dancer's flexedlegs add considerablyto the general restlessness of the panel design.'9 Eshu stands between men and gods as mediator and agent The Yoruba provocateur. believe that it is Eshu who tricksmankind into offending the gods, therebyproviding themwith sacrifices. Since the Shango priestwears his laba to the house struckby lightning where he announces what sacrifices must be made in expiation of the sins Shango is punishing,a portrayalofEshu, the instigator ofthe sin,on thebag containingShango's vengefulthunderboltseems appropriate enough. The Yoruba say that Eshu must be given a good part of the sacrificesmade to all the orisha(gods) since it is he who provides the orisha with food. Since Eshu is held responsibleforhuman follyand vulnerability,he is seen as the forcethat makes men turn to the gods in acknowledgementof

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

30

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

theirimperfections and foraid in theirendeavours. Each of thosegods who, it mightbe supposed, could support themselvesthroughtheircommand of the forcesof swift retribution is shown in mythto have come in conflict and been with Eshu, to have forcedto admit the necessityof his role. In one myth,forexample, each thunderbolthurled at Eshu by Shango shattered into a thousand fragmentsand were flung back at him. Shango had consequentlyto make peace with Eshu, and thereafter sacrificesprovided by Eshu were readily shared with him. In mythsand rituals one sees Eshu's two-way involvement;he promptsmen to offendthe gods, and aids the gods in theirvengeance. come to visita Shango priestwhen he was holding We have witnessedEshu worshippers and accept a gift fromhim; and we have also an inquiryat a house struckby lightning, seen Shango transvestites attend the annual dancing festivalin honour of Eshu and receive a giftas well (Plate IV B). The head possessionpriestin Oyo (the Odejin)during his annual celebrationin worshipofShango goes accompanied by hissubordinatesto pay he pauses at the centralshrineforEshu homage at the Magba's shrine; while returning, ofEshu (the Eni Oja) prostrate in the Oyo marketwherehe and thechiefpriest themselves out of respectforeach other. These examples demonstratea recognitionon the part of relationbetweenthethundergod and thetrickster. theYoruba ofthe mutuallysustaining If the panel design on the laba has been derived froma stylizedsign forlightning, it it should have been transis now becoming evident why, granted anthropomorphism, formedinto an Eshu-like being. Shango needs Eshu as much as do the othergods, but besides this he shares with Eshu many characteristics. Among other thingsthey share and a great resistanceto external authority.But the most common elean impetuosity mentin the mythsand songs about Shango and Eshu is power. The mythopoeicimagination does not, of course, use a symbol merelyto restatean otherwiseadequately definedconcept. On the contrary, symbolicformsare an importantmeans of formulating and communicatingwhat the imagination is strivingto grasp. The dominant conception which emergesin thisinstance is a resultof the constellationof qualities relatingto power. Praise songs of Shango and Eshu show some interesting parallels in Yoruba conceptionsofthe two gods, as may be seen in theseexamples: Take the entrance (i.e. do not come secretly throughthe back ofthe house). ... Do not do to me what I should not like, Terrible man who sat silently amongstthem, Do not do to me what I should not like, Do not let me suffer, is forgotten. One who suffers ... Mounting the roofofthe unbeliever He jumped on the child, on the child's head. Warriorgreatenough to avenge any slight, down a man's house to extendhis own. He struck ... He is the one theyworshipin our house. He killsso that Magba may eat freely (ofatonementfees). ... Shango do not let Magba take away mygoods. he also killstheinformer. ... If he killsthe transgressor,

Shango:

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

31

My husband, do not wrestlewithme Your wrestling tearsoff the child's arm. If he lifts up the anvil stone (to hurl) he will not pant. He stretched up, he stretches out ... He has a rope in his pocketforthe wicked. He came throughthe gutterof the house on horseback (i.e. when people were on guard againsthis comingthroughthe gate). Man of i6oo clubs, He broughtout forthe quarrellersa wooden rod. Eshu, you are in heaven workingon the world. One whom Eshu is workingon won't knowit. If he leaves his own house faraway A housholder'shouse he will take. One whom Eshu is workingon won't know it ... Eshu, don't workon me-work on the child ofsomeone else. ... He spread out a festival clothin the house ofthe heedless. All in our house pay heed to Eshu. Eshu, don't spread a festivalcloth in our house (i.e. a new cloth to receive gifts he has exacted). ... He stood at the pounded yam seller's and did not buy (i.e. but he kept other customers away, makingthevendor angry); He stood at the pounded corn seller'sand did not buy. His teethgrinding like stones, He comes out bringing his club. Eshu will beat the child and make him cryunceasingly, Greatest-to-be-seen withthe big wooden rod. It would be justifiable to characterize this power as phallic, particularlysince the phallus is prominentin the imageryof both Shango and Eshu. Eshu's head-dress,the first of many elementsleading us to postulate a representationof him on the laba,is as a sometimescarved as a phallus (Plate III). The phallus alone, in fact,oftensuffices of Eshu. Its displacement- that is, the phallus as head-dress-implies representation that it is not in its procreativefunctionthat the phallus is an attributeto Eshu, a conclusion supportedby Eshu mythand ritual. In his praise songs,the penis is referred to, not in connexion with procreation,but as related ratherby its autonomous nature to Eshu's caprice. One instrument of Eshu's power is a club, which in the mythshe puts into the hands ofthosewho are quarrelsome,and withwhich he strikes thosewho do no' fully respecthis power. Shango's thunderbolt, anotherphallic instrument, appropriatel) in the hands of a kinglygod, similarlytakes our attentionaway froman association of the laba with the thunderstorm's regenerativerain, and stressesinstead vengefuland destructive power. Another of the phallic qualities that dominate Eshu and Shango is self-assertion and masculine striving.All these qualities are equally responsible for conflicts withthe social orderengenderedby individual wilfulness.

C

Eshu:

J R.A.I.

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

of the King Shango tell of his capricesand love forpower; how, for The myths he had yieldedto thewhimto play heedlessly withhismagicand in so doing example, had destroyed his palace, and manyof his subjects. His praisesongs,on the himself, a widerangeofphallicqualities, other hissexuality and the hand,emphasize including he givesto hisworshippers. Butiftheimagery on thelabaserves fecundity to emphasize a particular itis thatin whichhe most aspectofhispower, resembles Eshu. The posture in a gesture arms ofthepanelfigure-the at onceofviolence and likea conventionalized lightning flash-directs our attention away from sexuality towardsShango's role as in which hisparticular he useslightning, ofenergy, avenger, as a punishment. expression randomness withwhichShangohurls The seeming hisboltsand Eshu demonstrates his if not the wilfulness has, so we are told,a purposethatshowsthe inter-relationship ofthegodswithmankind. concern in a natural Shango'sangerand power, encountered is equated withEshu's,whichis manifest in humanstrife; force, theyappear together on thelaba because each reinforces theother.What at first seemsto be a sharedantias a demandthatindividual or grouptakeintoaccountthe social aspectrevealsitself plansofthegodsand therequirements ofthewholeofsociety. The twogodsEshu and and condensed in a symbol Shangoare fused lack distincbecause,at somelevels, they is no surprise in view tion; and thatEshu comesintothisdesignmaskedand disguised ofhisrole. In thedesign on thelabapanel,form, morethancolour, reveals The colours meaning. are a relatively offorces as itwere,thecharacters simple statement concerned, marking, involvedin the drama,while the intricately subtleform is morecomplexand more Butifwe turn theshapestoconsider evocative. nowfrom thecolours ofthepanel, briefly we see thatthecut-out is traditionally in blackand white. decorated yellow figure These forEshu in his cult.20 The backcolours-yellow,black and white-are emblematic forthefigure is red,traditionally theprincipal ground colourforShango,whichseems too appositeto thecharacter ofthethunder The patchesof comment.21 god to require makeup thecolours withtheir greenin thecorners yellowborders together properto as well as therelationship destinies Ifa, theYoruba oraclewhichrevealsto men their thegodsand bothsociety and theindividual. between In Yorubacosmology, Ifa and Eshuare companion-mediators between thegodsand is thecounterpart oforderliness and ofpredictability, of men; and Ifa, as theprinciple strife and can therefore as theunEshu,whowilfully occasions be mostaptlydescribed Eshu prompts mento offend thegods; Ifa tellsmenhowthey certainty principle.22 may placate them.In Yoruba thought, oftheone is necessary to theexistence theexistence oftheother, so it is to be expected ofconflict thatwhenwe find thecolours and symbols (thoseofShangoand Eshu) in themiddleofthepanel,we shouldfind also thecolours ofresolution symbolic (thegreenand yellowofIfa) at theperipheries. Widelyknown show is an example ofthe myths howIfa and Eshusustain each other;their relationship balanceddualismthatpermeates all Yoruba religious and cosmological conceptions.23 On thelabawe find thestatement andmotion that violence must be surrounded byorder, contained by rest. But order, mustnevertheforthesakeofrenewaland development, lessbe broken(and it can perhapsbe considered a concession to Eshu thatthepatches ofgreen, thesquarepanel, though each ofthefour ofthedesign they mark corners within are all differently the characters and shaped). The coloursthen,by stating involved,

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

33

form in asserting thatviolence also through their mustbe emotive quality, supplement isvaluedpositively. controlled, butthatdisturbance The storm The turbulence ofthelabapanelis analogous to thatofthethunderstorm. itself is violent, itsnoisydestructiveness and wanton.But can be feltas uncontrollable thestorm in therhythm ofnature, thetransitions is limited, having itsfunction marking the heaviest of Eshu, rain. The activities betweendryand wet seasons,and bringing thesocialorder, but markinlikethethunderstorm, are bounded,and do notdestroy in thecompetition of stead the transitions and changemanifested between stagnation individuals, vested interest, and factions within therelatively stablesocial for advantage order.Whilethe activities of bothEshu and Shango bringabout limited destruction, bothensure oflife. ofEshu theregeneration ofthevarious forms We mayseein themyths a parable to the effect -the of will would cease to thatmankind without promptings theinterand society and culture theYoruba say thatwithout strive, wouldstagnate: thelandwould vention ofEshuthegodswouldstarve and vanish;andwithout thestorms are all in accordwith nothaveseasons and hunting. Theseanalogues ofgrowth, harvest, a moregeneralunstated in the and one thatis implicit axiom ofYoruba cosmology, socialsystem as muchas in thereligious: their and thatall extremes generate opposites; it insteadin a further, ofconflict, and by containing through avoidingthesupression state ofbalance,society makes itvaluableand constructive. For instance, Eshu singers ofEshu,celebrating after theyhave sungthepraises his tricks, hisspreading and hissatisfying and hisworshippers ofdisorder, himself through the sacrifices ofothers, to God, the follow witha hymnthattheysaid was addressed thatwe everheard): KingofHeaven (theonlyoneso addressed We cannot turn from theHouseoftheWorldand live . . . Eshu'sdevotees forthemarket theLord ofHeaven created ... givethanks -(Eshu is most active in themarket). The children ofthedwellers on Eartharenottooverthrow it. ownking, withpraiseofthejusticeoftheir theAlafin ofOyo, and They thenconclude In otherwords, sing his praisenames and thoseof his mostrenowned predecessors. Eshu's disorder is balancedby itsopposite, thejust law oftheking, and bothare containedwithin thecreated world.The praisesongsand myths, then, saypoetically what we haverephrased as a metaphysic. (supported bymuchother material) We mayfinally thelaba as a whole.On thefront, consider thefour-times repeated an aspect of Shango's poweris orderedinto a pattern panel designrepresenting of absolute Butwithin thepanel all is asymmetry and disorder, symmetry. becauseopposing Ifa-for whomsymmetry and thenumber four are symbolic-isthewilful trickster thatexplores Eshu, the dynamicenergy and promotes change.In this connexionit shouldbe recognized thatthelabais composed ofsquaresand triangles; without going valuestheYoruba find in numbers, thattheseven deeplyintothesymbolic we suggest tassels from thetriangular hanging laba (quiteapart piecesat thebottom edgeofevery from considerations ofwhatever historical linkswiththe Mediterranean or Near East the statement made by the designon the laba-the theymay indicate) summarize and fourness. unionof threeness To the Yoruba fouritself signifies completeness and

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

of Ifa. In the realmof the symmetry; orderand the numberfourare all properties and visiblerelationship sacred,fourconveys the structured, comprehensible, between to theYoruba is partofthe godsand mankind revealed through Ifa. The number three and signifies symbol complexofthedeified Earth,thehomeof the ancestors, mystery (Morton-Williams for thethunderbolt thatShangohurls I960). The labaas a container to theearthis symbolically to theearthwhichreceives equivalent Shango'slightning. The number symbolism asserts thattheunionoffourand three(each withitscosmoa symbol logicalsignificance) produces a number which is itself indivisible, and therefore ofthecreation ofa newform from theunionofopposites. Seventhenis thesummation ofwhatis gropingly and thatwhichis intellecapprehended through symbols (three), formulated tually (four). to the powerful Magically,the laba is equal in strength destructive thunderbolt in it.As we have asserted thethunderbolt to be symbolically which can be safely carried feminine. seemsto us to so is the laba symbolically Its feminine character masculine, have been established in therite whenit was secretly openedby Shango'shighpriest ofYoruba dualism, to Shango'sservice. in terms thepotency ofdedication Speculating whenit is contained in thelaba;24 and we and dangerofthethunderbolt is neutralized of theseartifacts see repeatedin the ritualbringing the searchforunion of together masculine and feminine traits manifested in thetransvestitism ofShangopriests.25 ofEshu,carries The swastika itself, whichcan be tracedin thedancingfigure these and equilibrium meanings too; in it are foundthe qualitiesof bothtension whichtoa feeling balance.Thisdynamic balancematches thelicensed ofdynamic gether produce movement abandonofShangoand Eshu.And therotary suggested bya swastika speaks and which is notpossible oftheeternal whichEshustands, theinterchangefor without ofopposites. thelaba panel operates from disAs a symbol, mingling quite differently a multiplicity ofmeanings and in so doing coursein thatit can present simultaneously, are by their But symbols to channelassociations and apperceptions. serves verynature of and meaningcan continueto be drawnfromthemboth in terms inexhaustible, Yoruba and ourownculture. ofthemeaning ofthelaba,its WhiletheYoruba seemto have lostanyexplanation has none the less survived. In our social function, as is often the case withsymbols, ofthelabapanel corresponds we have sought to makeclearthatthesymbolism analysis in every detailwith itsritual meaning and use; and ourargument concerning themeanfound ingofthelabagainsforce bytheconsistency between symbolic meaning and ritual function. The care withwhichthelabais made,thestrictness withwhichthepattern is accordwiththeprominand theconspicuousness withwhichit is displayed, conserved, ence it acquires through and highlydistinctive item of ritualparabeing the first phernaliathat the new priestof Shango mustobtain. We have made our analysis include everydetail of the designthat we can distinguish, and have shown each ofthelaba. Moreover, form symbolic to contribute to thereligious meaning thesacraof the decoration mentof its openingby the Magba and the symbolism the clarify reasonwhythethunderbolt in it. The symbolism, must be carried is although complex, constructed thefirst and on onlytwoprinciples, beingthatofclarification by analogy, ofthegiventhrough thesecondbeinga heightening theawareness of oftheexperience itsopposite.

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

35

of the culturaldrama the and emblems The laba bears on its coverthe symbols ofEshu,Shango's theprovocation through strikes: Yoruba see enactedwhenlightning the agencyof Ifa men learnhow to are loosedupon mankind;through thunderbolts ofthegods. thedemands with grow

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

the carvingin J. T. Hooper, Esq., forallowingus to photograph We wishto thank and colleagueshave earned our thanksby givingus their Plate III. Many friends too, to manyof themfor to the designon the laba panel. We are grateful, responses of the of the staff of the paper, especiallyto members on drafts helpfulcomments to Mr Robin at University College London, particularly Department Anthropology and Dr Leopold E. H. Gombrich Horton;and we shouldalso liketo thankProfessor their helpand encouragement. Steinfor

NOTES about theYoruba,butmuchofthedescription to Shangoin publications 'There are manyreferences and (b) material-well illustrated-is in (a) Frobenius(I9I2), The best ethnographic is misleading. Verger(I 957). 2 The carrying ofthelaba has fallenintoabeyancein Oyo duringthelast fewyears.It appears that was in 1954 or 1955. ofpriests procession thelastfulldress 3 Frobenius We notethathe picks ofAfrica. ofa laba in The Voice by Carl Arriens includesdrawings thattheselaba,made as we do; and further, ofthe designas the main structure out thesame elements thesameas theone made in I957. I9I0, are substantially before panels. 4 In towns in thefront theusual decorations otherthanOyo we have seen a fewlaba without Town(Lagos, The Nigeria OneSmallroruba from ofSacredWoodcarvings H. U. Beierin his book TheStory milesfrom Oyo), showing takenin Ilobu (about fifty 1957) has includeda photograph MagazineOffice, but overthe hang not in theshrine thatthesetwodeviantspecimens twounusuallaba. It is noteworthy weremade,ifin Oyo at all, byanother these Possibly oneshangwithin. whileother conventional entrance, of the Osi Shona perhaps,who have asserted lineage-by the members of the leatherworkers' segment laba from that theyknowhow to make them.They did not claim thatthe Magba ever commissioned that some him suggests to make themforus withoutconsulting them,and the factthat theyoffered in thisverylikely oftheirshrines, have obtainedlaba,probablyforthe decoration Shango worshippers way. lesscostly ofthemas recent do occur,we are inclinedto think to the colourarrangement 5 Whereexceptions and decadentvariations. 6 In theIyaji wardofOyo. handingit overto be paid foropeningthelaba before 7He declaredthatthefeehe would ordinarily to would be twoguineasand somegin,and he would in additionrequirea cock forsacrifice the priest animals,e.g. the ram, the Magba can take animals (Shango's set of sacrificial Shango. Alternatively, to Shango) fromthe new priest.All thisis kola (also appropriate snail, and cock) and bitter he-goat, whichwas about C7. beyondthecostofthelabaitself, 8 The 'aradung' ofFrobenius. they. replaced the oshe the cult of Shango into theirreligion, 9 When the Dahomians incorporated by an axe witha singleblade. Examplesheld by devoteesofXevioso,the Dahomian Shango,are illusan showing a photograph in thesepublications to find trated by P. Verger(1952; 1957). It is interesting metalaxe (Plate 55). Jean Rouche (I960) in Brazilto be a double-bladed oftheShangoworshippers oshe axe from Shango.In Songhaithethunder theSonghaithunder god Dongo to have beenderived considers of the has a singleblade and a bell on theback ofthehandle (Plates I and VI). The outwarddiffusion in difficult to tracethe routeby whichthe main elements Oyo makesit particularly Shango cultfrom reachedOyo. thiscomplex

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

36

JOAN

WESCOTT

&

PETER

MORTON-WILLIAMS

10Thus, notonlydoes it appear thatno myths about thelaba are current, but likewise none concerning thedouble-headed axe (an implement notutilizedby theYoruba) on whichthewoodendance staff is modelled.This staff a carvedskeuomorph. is unmis(oshe)is often Yet, althoughthe representation takable,the Shango worshippers do not recognize it to be one, thoughwiththe oshe theyinsist, just as they do withthelaba,thattheform be preserved. Il This,generally speaking, is trueofall Yoruba cults.The Magba, however(and othercultofficials of the centralShango hierarchy), may not alwaysexhibit personality traits matching thoseof theworshippers and thegod sincehispostis hereditary, and generally passesbyprimogeniture. 12 This of coursemustbe shammed. Shango personalities are usually very adept at thisand many other kinds ofconjuring. "I The left side and thediagonalline in theritualand art ofotherYoruba cultswill be examinedat in our forthcoming somelength has analysedthesigbook on Yoruba art and religion. Evans-Pritchard nificance ofa similar consciousness ofthemeaning oftheleft sideamongtheNuer. 14 The effect ofthediagonallinecan be seenmostclearly in Baroque and contemporary sculpture and painting. 15Apartfrom the conventionally abstract forms ofthe Yoruba denotative signsseen on thewalls of someshrines. For an exampleofthistypeofmuralartsee thephotographs on pages 2 I 9 and 221 withour articleentitled 'The FestivalofIya Mapo' in Nigeria Magazine, no. 58, 1958. 16 The doubleaxe is a symbol forJupiter as wellas forShango. 17 Another striking parallel suggested by the designwhichoughtnot to be ignoredis thatbetween Eshu and theWestAfrican fablesofthecleverand conspiring spider, particularly in viewofthefactthat the designitself was seen by manyWesterners to resemble a spider.Since a symbolcondenses and can containmanymeanings, a swastika, a spider,and Eshu can simultaneously appear in a configuration whichlinks their common features. 18Returning again to Evans-Pritchard's analysisofNuer ideas concerning the left and right sides,it is theleft hornofa man's ox, thebeastwithwhichhe is in manywaysidentified, whichis traineddownwards. "I Of some fifty about thirty occidentalsto whom we have shownthislaba panel decoration, have perceiveda figure in a dance position. Concerning thespirit ofthedance, manymoodsweredescribed: whilevigouris commonto all, he is seen as jubilant,violent, boisterous, threatening, jocular, and so on. thata wide rangeof emotions is Perhapsthe truest understanding comeswithacceptingthe possibility at once contained. 20 We have recently in a pattern cotton cloth seenthesecolours on an imported wornin combination whichwas made up as the uniform attireof the Oyo Eshu worshippers fortheirannual festival. (See Plate IVB.) 21 Thoughit does receive not onlyto comment in a Shango praisesongwherethered is said to refer someis poured thered-dyed clothes ofthepossession butalso to theblood ofsacrifices, priest, which,after on thecultobjects, is pouredoverthepriest whilehe is in possession. 22 This apt metaphor in conversation withMortonforEshu was coinedby Professor N. A. Barnicot in 1950. Williams 28 in other Eshu (Elegbara) and Ifa are beingtreated at somelength papersin progress. 24 When,after theground'by thepriest, has been 'dug from he has struck, thethunderbolt lightning puts it intoa bowl ofpalm oil to 'cool' it. This is an interesting parallelwiththeYoruba rule thatthe mud pillarin Eshu shrines mustbe kept'cool' withpalm oil pouredoverit daily; wereit to becomedry, Eshu's mostdestructive trickery would bedevil thosewithinthe parish of the shrine,whetherhouse compound,or thewhole town.The Shango priestcarriesthe thunderbolt away onlywhenall thefines have beenpaid and atonement made. 26 This feature, and others oftheShangoritual, willbe takenup in a subsequent publication.

REFERENCES TheVoice FROBENIUS, LEO 19 12. Und Afrika Sprach. Leipzig. (Engl. trans., ofAfrica. London, 1913.) MORTON-WILLIAMS, P. I 960. The Yoruba Ogboni Cult in Oyo. Africa, 30, pp. 362-74. ROUCHE,JEAN I 960. La Religion Songhai.Paris. VERGER, PIERRE 1952. Dieuxd'Afrique. Paris. (Esp. Plates62, 63, 68.) no. 5I, VERGER, PIERRE 1957. Notessurle cultedes Orisa et Vodun. Mim.Inst. d'Afrique Noire, Franfais pp. I-609. (Same platesas in Verger1952.)

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE

YORUBA

LABA

SHANGO

37

LEGENDS TO PLATES actualsize. (Key to colours in drawing opposite Plate I.) I. The panel design, in the top centre.In thelowerleft II A. A Shango shrine in Iseyin,Oyo Division.The laba is hanging is besideit lying is a black wood figure forEshu. The head-dress ofanother broken Eshu carving corner The trayrestson an upturned on the ground.Justbelow the laba is a trayfilledwith'thunderbolts'. and a secondmortar is in the right These mortars are both the carvedmortar, odoShango, foreground. withsacrificial blood and oil-and also theproperseatfor proper support forthestones-and are wetted a possession priest. carrying the II B. A figure in the royalShango shrineat Koso (Oyo) showing a Shango worshipper laba. forEshu. (Collection Ritual carving III. J. T. Hooper, The TotemsMuseum,Sussex.) This is one of Two otherphallicobjects, instances knownto theauthors. themoststriking ofEshu's phallichead-dress are heldin either hand. hisclub and hismedicine container, just dancingat theannual festival IV A. An Eshu worshipper (I957) forthegod in theAkesanmarket in Oyo. The coloursofhisgownare black and whiteon a yellowbackEshu shrine outsidetheprincipal ground. in Akesan market, on the rightis Oyo, I957. The Eshu worshipper IV B. The annual Eshu festival a male devoteeofShangoheredressed for theoccasionin female a gift attire. receiving from

This content downloaded from 200.17.215.230 on Fri, 27 Sep 2013 09:15:25 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Transcendental Magic (1896)Dokument276 SeitenTranscendental Magic (1896)SithSaber94% (17)

- Odu 16Dokument20 SeitenOdu 16adext100% (1)

- Metaphysical Principles in OduDokument2 SeitenMetaphysical Principles in OduOungan Vincent96% (24)

- The Witches, Iyami OsorongaDokument7 SeitenThe Witches, Iyami OsorongaHazel100% (3)

- Concepts of Humam Personality and Ori (Inner Head)Dokument16 SeitenConcepts of Humam Personality and Ori (Inner Head)Gabriel Mallet Meissner100% (2)

- Guiding Principles - Oracle IfaDokument2 SeitenGuiding Principles - Oracle IfaDaniel John100% (1)

- Chief Fama 1Dokument2 SeitenChief Fama 1Wallkyria Galactica100% (5)

- IBEJI - Spirit of The TwinsDokument3 SeitenIBEJI - Spirit of The TwinsHazelNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH. 8 - Osun and Brass - An Insight Into Yoruba Religious Symbology - Abimbola PDFDokument11 SeitenCH. 8 - Osun and Brass - An Insight Into Yoruba Religious Symbology - Abimbola PDFHazel100% (2)

- Beginner's Guide to Kolanuts DivinationVon EverandBeginner's Guide to Kolanuts DivinationBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Path of Initiation in IfaDokument5 SeitenThe Path of Initiation in IfaИфашеун Адесаня100% (3)

- The Multidimensional OSUNDokument13 SeitenThe Multidimensional OSUNBianca Lima100% (4)

- Aworan, Representing The Self and Its Metaphysical Other in Yoruba Art by BABATUNDE LAWALDokument9 SeitenAworan, Representing The Self and Its Metaphysical Other in Yoruba Art by BABATUNDE LAWALWole LagunjuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifa Divination Odus - Ogbe e OmodusDokument17 SeitenIfa Divination Odus - Ogbe e OmodusLuiz Carvalho100% (1)

- Iyalawo - WikipediaDokument33 SeitenIyalawo - WikipediaEl ibn s'ad100% (1)

- Ifa 11Dokument5 SeitenIfa 11siddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- JESUS OLÓFIN ÁLÁ, Was Initiated in Yorubaland Into IFÁDokument2 SeitenJESUS OLÓFIN ÁLÁ, Was Initiated in Yorubaland Into IFÁAwo Ifalenu Yoruba-Olofista100% (1)

- OvDokument2 SeitenOvCarl Thornhill100% (1)

- Iyami TranslatedDokument38 SeitenIyami Translateddingy555100% (1)

- Death Before Our Time (Ifa Foundation)Dokument2 SeitenDeath Before Our Time (Ifa Foundation)Ijo_BarapetuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifism I ADokument10 SeitenIfism I ACastro Eduardo Fabio100% (1)

- Hebrew To English Kabbalah Dictionary - FreeDokument16 SeitenHebrew To English Kabbalah Dictionary - FreeVirgílio MeloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 21 Revised PDFDokument23 SeitenModule 21 Revised PDFrolando100% (5)

- Baba Osundiya Basic Obi AbataDokument20 SeitenBaba Osundiya Basic Obi AbataAwo Ifaleye60% (5)

- SHANGO - God of ThunderDokument4 SeitenSHANGO - God of ThunderHazel100% (2)

- Metaphors ManualDokument0 SeitenMetaphors ManualZe Ro100% (1)

- Oya Study Guide FINALDokument8 SeitenOya Study Guide FINALDele Awodele75% (4)

- Four Day CycleDokument3 SeitenFour Day CycletataKuceroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whirling Cloth, Breeze of Blessing: Ancestral Masquerade Performances Among The YorubaDokument8 SeitenWhirling Cloth, Breeze of Blessing: Ancestral Masquerade Performances Among The YorubaThomas Schulz100% (2)

- Ifa 9Dokument20 SeitenIfa 9siddharthasgiese100% (1)

- About Yemoya and The Different Manifestations of The IrúnmolèDokument2 SeitenAbout Yemoya and The Different Manifestations of The IrúnmolèBaba-ifalenuOyekutekundaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MeyisDokument48 SeitenMeyisodditrupo100% (2)

- Osun pdf-1Dokument3 SeitenOsun pdf-1Iya EfunBolaji50% (2)

- JakutaDokument3 SeitenJakutaSephira Richard100% (2)

- Mason Olokun Words 1 1Dokument86 SeitenMason Olokun Words 1 1Klenyerber Lucena Chacon100% (3)

- Who Is An IyanifaDokument3 SeitenWho Is An IyanifaHazel Aikulola Griffith100% (1)

- Ancient Ile IfeDokument36 SeitenAncient Ile IfeRocío Basurto RobledoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yoruba Personal Names PDFDokument13 SeitenYoruba Personal Names PDFBianca LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metis Residential Schools Aboriginal Healing FoundationDokument177 SeitenMetis Residential Schools Aboriginal Healing FoundationBev Weber100% (2)

- Osogbe RosoDokument91 SeitenOsogbe RosoOse Omoriolu100% (2)

- RACEwhiteladyafricanspirituality 09Dokument30 SeitenRACEwhiteladyafricanspirituality 09OmoOggunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hand of OrulaDokument1 SeiteHand of OrulaNelson Sotolongo100% (1)

- 2Dokument17 Seiten2Wender MirandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yoruba Belief About The Days of The WeekDokument2 SeitenYoruba Belief About The Days of The WeekHazel Aikulola Griffith100% (3)

- Yemọja oDokument1 SeiteYemọja oSergioferreira FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iyaami-Em InglesDokument2.711 SeitenIyaami-Em InglesEsoterikaMagia33% (9)

- A Lecture On Oshun and GelefunDokument11 SeitenA Lecture On Oshun and GelefunHazel100% (1)

- 5 Facets of OriDokument5 Seiten5 Facets of OriadextNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oshe TabooDokument4 SeitenOshe TabooSergioferreira FerreiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- How OLÓKUN ÒRUN Came Out of OLODUMAREDokument2 SeitenHow OLÓKUN ÒRUN Came Out of OLODUMAREAwo Ifalenu Yoruba-Olofista67% (3)

- Awo Training Part 9Dokument2 SeitenAwo Training Part 9Arturo ChaparroNoch keine Bewertungen

- OGUN - God of IronDokument3 SeitenOGUN - God of IronHazel100% (2)

- Olodumare: God in Yoruba Belief and The Theistic Problem of EvilDokument17 SeitenOlodumare: God in Yoruba Belief and The Theistic Problem of EvilalagemoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Needs. A Pocket Service Book of The Holy Orthodox ChurchDokument230 SeitenBook of Needs. A Pocket Service Book of The Holy Orthodox ChurchΜένιος Κουστράβας100% (1)

- Empire of The Petal Throne Deeds of The Ever-GloriousDokument103 SeitenEmpire of The Petal Throne Deeds of The Ever-Gloriousrooster1512100% (3)

- Women in Orisa Worship and IFA EsuDokument10 SeitenWomen in Orisa Worship and IFA EsuHanibal LexterNoch keine Bewertungen

- IFA-Concept of OriDokument15 SeitenIFA-Concept of OriHector Javier Enriquez100% (6)

- IBEJIDokument4 SeitenIBEJIaganju99950% (2)

- Ìṣẹṣe Yorùbá Cosmology - It's Function and UseDokument2 SeitenÌṣẹṣe Yorùbá Cosmology - It's Function and UseOdeku OgunmolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study of Yoruba Civilization and The Importance of PhilosophyVon EverandStudy of Yoruba Civilization and The Importance of PhilosophyNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Ifa Diviner's Shrine in IjebulandDokument11 SeitenAn Ifa Diviner's Shrine in IjebulandOlavo Souza100% (5)

- Understanding Ebbos by Iyanifa Ifalade TaShia AsantiDokument5 SeitenUnderstanding Ebbos by Iyanifa Ifalade TaShia Asantisacred_door80% (5)

- Shango Limited EditionDokument5 SeitenShango Limited Editionlevysinho67% (3)

- Ibeji CultDokument15 SeitenIbeji Cultmambanegra767% (3)

- The Orisha Sacred Songs of TrinidadDokument4 SeitenThe Orisha Sacred Songs of TrinidadCarlene Chynee LewisNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Exploration of Odu Ifa: Click HereDokument5 SeitenAn Exploration of Odu Ifa: Click Heredeibys velasquez0% (4)

- Historical Foundation of EducationDokument18 SeitenHistorical Foundation of EducationJennifer Oestar100% (1)

- Nock - Conversion-The Old and New in Religion From Alexander The Great To Augustine of Hippo PDFDokument159 SeitenNock - Conversion-The Old and New in Religion From Alexander The Great To Augustine of Hippo PDFEusebius325100% (1)

- Blessing of A BellsDokument4 SeitenBlessing of A BellsClyde ElixirNoch keine Bewertungen

- I .Ip.I Lu Sı D, Iıı$Cr, Instructions For Stoppiııg Hood,, 1 U I LLL, Irl, Lı Ates. T Lists The Bud Dayı of T14C YeatDokument195 SeitenI .Ip.I Lu Sı D, Iıı$Cr, Instructions For Stoppiııg Hood,, 1 U I LLL, Irl, Lı Ates. T Lists The Bud Dayı of T14C YeatMarshela PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evangelium Veritatis and The Epistle To The Hebrews - Soren Giversen PDFDokument11 SeitenEvangelium Veritatis and The Epistle To The Hebrews - Soren Giversen PDFjusrmyr100% (1)

- Why I Converted ToDokument44 SeitenWhy I Converted Tosandumihalcea1673Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rituales y Symbológía YorubaDokument12 SeitenRituales y Symbológía YorubaAnonymous oWfvewQfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Triumphal Chariot 00 Basi RichDokument254 SeitenTriumphal Chariot 00 Basi RichsiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adivianhaçao 70Dokument1 SeiteAdivianhaçao 70siddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aqui hj4Dokument1 SeiteAqui hj4siddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poke RunyonDokument1 SeitePoke RunyonsiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- About Bnei BaruchDokument2 SeitenAbout Bnei BaruchsiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 CEO Performance Evaluation Survey With The Miles GroupDokument19 Seiten2013 CEO Performance Evaluation Survey With The Miles GroupStanford GSB Corporate Governance Research InitiativeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SalomãoDokument118 SeitenSalomãosiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Driving Strategic ImpactDokument2 SeitenDriving Strategic ImpactsiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estrategias de Aplicacao - PolimerosDokument89 SeitenEstrategias de Aplicacao - PolimerossiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifa 13Dokument13 SeitenIfa 13siddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 CEO Performance Evaluation Survey With The Miles GroupDokument19 Seiten2013 CEO Performance Evaluation Survey With The Miles GroupStanford GSB Corporate Governance Research InitiativeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ifa 16Dokument7 SeitenIfa 16siddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of Terms Related To Pharmaceutics (IUPAC)Dokument29 SeitenGlossary of Terms Related To Pharmaceutics (IUPAC)José BocicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orisanmi StudyguideDokument18 SeitenOrisanmi StudyguidesiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 Fall CalendarDokument1 Seite2013 Fall CalendarsiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cto Sample ScheduleDokument1 SeiteCto Sample SchedulesiddharthasgieseNoch keine Bewertungen

- West Africas Orisha and AstrologyDokument5 SeitenWest Africas Orisha and AstrologyMariyaSkalozhabskayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Heavenly Father Expects From Earthly FatherDokument4 SeitenWhat Heavenly Father Expects From Earthly FatheranalynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inclusive LanguageDokument5 SeitenInclusive LanguageakughaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jesus: Prophet, Priest, and KingDokument2 SeitenJesus: Prophet, Priest, and KingMay Chelle ErazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- EKuehn - MELCHIZEDEK AS EXEMPLAR FOR KINGSHIPDokument19 SeitenEKuehn - MELCHIZEDEK AS EXEMPLAR FOR KINGSHIPaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sumerian OccupationsDokument27 SeitenSumerian OccupationsSeikkenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rite of Baptism For Children,: Mportance of Aptizing HildrenDokument6 SeitenRite of Baptism For Children,: Mportance of Aptizing HildrenMelisa MackNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christianity, Imperialism, and CultureDokument325 SeitenChristianity, Imperialism, and CultureRandall Hitt100% (1)

- Missalete For Priest (09-10)Dokument14 SeitenMissalete For Priest (09-10)immortalsharkzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psalm 133 Commentary by Nancy Koester - Working Preacher - Preaching This Week (RCL)Dokument2 SeitenPsalm 133 Commentary by Nancy Koester - Working Preacher - Preaching This Week (RCL)Osagie Alfred100% (1)

- Gs 1557Dokument302 SeitenGs 1557sectubNoch keine Bewertungen

- Washing The Feet of Women On Holy ThursdayDokument31 SeitenWashing The Feet of Women On Holy ThursdayFrancis LoboNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Spiritual PharmacyDokument5 SeitenA Spiritual PharmacyDinu Mihail-LiviuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Satanic Pope HOAX - HoodedCobra666Dokument4 SeitenThe Satanic Pope HOAX - HoodedCobra666cobracro2411Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Consecrated Way To Christian PerfectionDokument29 SeitenThe Consecrated Way To Christian Perfectionlwalper100% (2)

- Anointing of The Sick Praenotanda PDFDokument8 SeitenAnointing of The Sick Praenotanda PDFKENNETH ARVIN TAYAONoch keine Bewertungen

- 77 Thrones - The Theological CodexDokument184 Seiten77 Thrones - The Theological Codexdexter01Noch keine Bewertungen

- An Ideal FamilyDokument4 SeitenAn Ideal FamilyAdmiredandrew52Noch keine Bewertungen

- On The People of God: Lumen GentiumDokument6 SeitenOn The People of God: Lumen Gentiumjose kenneth greenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gorbachev's Perestroika Is A HoaxDokument3 SeitenGorbachev's Perestroika Is A HoaxThe Fatima CenterNoch keine Bewertungen