Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

GA Magazine 3.2008 Alt-Fuels

Hochgeladen von

alftoyOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

GA Magazine 3.2008 Alt-Fuels

Hochgeladen von

alftoyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

FUTURE

Researchers combine

efforts and explore

options in developing

alternative fuels

W

hen K.C. Das first started exploring

ways to convert wood chips into en-

gine fuel five years ago, people thought his

work was interesting—but not particularly

urgent.

“Five years ago, nobody really cared

because crude oil was cheap,” says Das,

associate professor of engineering and

director of UGA’s biorefining and carbon

cycling program. “Now it’s a big deal, and

everybody is calling and asking about what’s

going on.”

And there is a lot going on at UGA.

PAUL EFLAND

From wood chips to watermelons, switch-

Engineering professor K.C. Das uses UGA’s pilot-scale biorefinery, located just a few miles from grass to sweet potatoes, researchers

the main campus, to test new biofuels made from raw materials as diverse as wood chips and throughout the state are exploring opportu-

algae. nities to create new fuels.

30 MARCH 2008 • GEORGIA MAGAZINE

FUEL by Sam Fahmy (BS ’97)

Just a few months ago, the University liquor—and Rudolf Diesel, the inventor of Tifton campus are working to breed variet-

was awarded one of the largest grants in the engine that bears his name, used peanut ies of peanuts that produce large amounts

its history—nearly $20 million by the U.S. oil to power his engine. Ample supplies of of oil. Others are turning sweet potatoes

Department of Energy (DOE)—to search crude oil, however, put the brakes on the into fuels. Angle explains that sweet

for efficient ways to turn the tough, fibrous early use of plant-based fuels. potatoes grow well in Georgia, but our

parts of plants into ethanol, an effort that With the basic science of creating hard clay soil leaves them misshapen and

has the potential to increase dramatically biofuels understood, the task of UGA unappealing to consumers. The ugly sweet

the amount of biofuel the nation produces. researchers is to make the process more potatoes work beautifully as a source of

Das and a team of UGA researchers also efficient and, ultimately, cost competitive ethanol, so scientists are exploring how to

recently have developed an entirely new with petroleum. Waste products from ag- grow them efficiently for fuel production.

biofuel derived from wood chips. riculture, the poultry industry, forestry and “What we’re learning now is how to

“There’s a widespread perception, even from restaurants and bakeries have the grow them to cram as much energy per

including among legislators and the Gov- potential to fuel vehicles, power plants and acre as possible,” Angle says.

ernor’s Office of Economic Development, the state’s economy.

that bioenergy constitutes a great oppor- “Agriculture is the state’s largest Revolutionizing ethanol

tunity for Georgia,” says David Lee, vice industry, but this is a very difficult time Most of the ethanol Americans use to-

president for research at UGA. “We have because of higher fuel and fertilizer costs,” day is derived from corn kernels, which has

the ability to be a leader in this area, and I says Scott Angle, dean of the College of driven the price of livestock feed up and cut

think it’s entirely consistent with our role as Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. into the bottom line of the poultry industry.

a land grant institution that we do so.” “If we can somehow take our waste prod- Prices of grains such as soy and wheat are

ucts, or maybe even an intentionally grown rising, too, as farmers devote more acres to

From farm to fuel crop, and turn that into useable energy, that corn and fewer to other crops.

The idea of turning plants into fuel could be the difference between keeping Turning corn kernels into ethanol is

isn’t new. Henry Ford designed the Model our farmers in business versus an uncertain a relatively simple process (moonshiners

T to run on either gasoline or ethanol—the future.” have been doing it for ages), but the tough,

intoxicating ingredient in beer, wine and With that in mind, scientists at the fibrous parts of plants are much more dif-

GEORGIA MAGAZINE • MARCH 2008 31

make what’s called cellulosic ethanol. biomass processing facilities, last year

Rather than using corn kernels or found himself describing the process at

other edible plants, the scientists hope to a roundtable with President George W.

turn agricultural waste such as husks and Bush.

stems into ethanol. Switchgrass, which “I’m not so sure if they’d believe me

doesn’t require much water or fertilizer to in the coffee shop in Crawford [Texas] if I

grow, is another candidate, as are fast- told them what he just told me,” the presi-

growing poplar trees. dent said, drawing laughter from those

Their task isn’t easy: Plants have gathered. “But it’s possible.”

evolved their tough cell walls to resist

disease, insects and climate extremes. The Economics

research team at UGA is made up of 10 Of course, a biofuel may be tech-

labs, each applying the insights they’ve nologically possible to produce, but not

gained from years of basic research into

how plants are put together and broken

down at the cellular level.

“Using wood to help meet our

“The exciting thing for me is having

all these teams of people from around energy needs is something that’s re-

campus coming together to address one

PAUL EFLAND

problem and to do it so well and so inter- newable and sustainable. We plant six

Alan Darvill and his team study plant cells actively,” Darvill says. “It’s fun.”

on a molecular level. The knowledge they The grant is funded by the DOE for trees for every tree that we harvest.”

gain will help them develop technologies nearly $20 million over five years. At the

that break down plants to create biofuels end of those five years, Darvill expects to —Dale Greene, professor, Warnell

more efficiently. have information that sets the stage for School of Forestry and Natural Resources

commercial applications that increase the

ficult to break down. nation’s production of ethanol.

That’s where Alan Darvill, who

has spent the past 20 years studying the Beyond ethanol

intricate structure of plant cell walls, comes Ethanol isn’t the only biofuel UGA

in. Darvill, co-founder and director of researchers are working with. They’re cre-

the University’s Complex Carbohydrate ating biodiesel from oils found in chicken

Research Center, is leading a team of UGA fat, seeds and even algae.

scientists who are collaborating with Oak They’re also pioneering a concept

Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee known as a biorefinery. Das explains that

and several other institutions to find just as an oil refinery takes a raw product

efficient ways to break down plants to like crude oil and converts it into gaso-

line, plastics, asphalt and 50 or so other

products, a biorefinery takes wood chips,

“The exciting thing for me is restaurant grease and other wastes and

converts them into biodiesel and non-fuel

having all these teams of people from products. One of the products is char,

which can be used as soil fertilizer. Putting

around campus coming together to carbon back into the soil as char offsets

some of the carbon dioxide pumped into

address one problem and do it so well the atmosphere by the fossil fuels.

“You have a valuable product and at

and so interactively.” the same time you are getting a net reduc-

ANDREW DAVIS TUCKER

tion of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,”

—Alan Darvill, co-founder and director Das says. Scraps of wood left behind after trees are

of the Complex Carbohydrate Research The biorefinery concept is so exciting harvested are a vast source of raw material

that can be used to create biofuels, says

Center that Ryan Adolphson, who directs UGA’s

forestry professor Dale Greene.

32 MARCH 2008 • GEORGIA MAGAZINE

economically feasible. John McKissick, the needs is something that’s renewable and

director of the UGA Center for Agribusi- sustainable, particularly the way forestry

ness and Economic Development, is an is practiced in the United States,” Greene

expert in putting a dollar value on the costs says. “We plant six trees for every tree that

and benefits of biofuel production. we harvest.”

“We’ve shown in our research early

on that the feedstocks that make the most Coordinated effort

sense were not the things that we grow UGA has more than 80 scientists,

exclusively for biofuels production, but engineers and economists who are working

from byproducts from other operations like on basic and applied biofuels research, and

fat from the poultry industry and leftover they aim to share their knowledge with

scraps of timber after harvesting,” he says. each other and with the government and

Dale Greene, professor in the Warnell private sector like never before.

School of Forestry and Natural Resources, Joy Doran Peterson is a microbiology

says the most valuable uses of harvested professor who is leading the University’s

wood are traditional products such as new biofuels task force. Her research

lumber and paper, but the small trees and focuses on understanding natural processes

wastes that are left behind are a promising that break down plants—like the process

source of energy. Greene has found that certain insects use to digest leaves—and TERRY ALLEN

having a wood chipper on site to process applying that knowledge to biofuel produc-

tree limbs, tree tops and other wastes can tion. As head of the task force, she aims to Ryan Adolphson, who directs UGA’s biomass

generate more than 10 tons of fuel per acre increase collaboration among the research- processing facilities, shows a handful of

that can be cleanly burned in electrical ers on campus and to make it easier for the wood chips that—thanks to research at UGA

—can be turned into an entirely new type of

power plants or refined to produce biofuels. government and private sector to connect

biofuel.

“Using wood to help meet our energy with the University’s experts. The goal of

that kind of partnership, she says, is to see

the University’s expertise applied to the

a biodiesel plant that opened last year.

real world as quickly as possible.

The company recently broke ground on

“I have two small children, and most

a second plant in Plains, and together the

of us in the group have a family of some

two plants will ultimately produce up to

sort,” Peterson says. “That really motivates

150 million gallons per year.

me and gives me a vested interest in mak-

UGA scientists have shared their

ing this happen now.”

expertise with Alterra in what company

Signs of the University’s involvement

CEO Wayne Johnson calls a win-win

in the biofuels revolution are already evi-

for the entire state. The plant primarily

dent in small towns such as Gordon, where

uses Georgia-grown soybeans as a source

Macon-based Alterra Bioenergy operates

of biomass, and Georgians manufacture

and distribute the fuel. Because biodiesel

burns cleaner than petroleum diesel, it

“I have two small children, and also benefits the environment.

“Without the research and leadership

most of us in the group have a family at the University, what we did would not

have been possible,” Johnson says.

of some sort. That really motivates

—Sam Fahmy is the science writer for the

me and gives me a vested interest in

UGA News Service.

ANDREW DAVIS TUCKER making this happen now.”

Microbiology professor Joy Doran Peterson GET MORE

says that natural processes that insects —Joy Doran Peterson, professor,

use to break down leaves may offer clues Bioenergy research at UGA:

microbiology and head of the UGA www.uga.edu/bioenergy

about how humans can break down plants

and create tomorrow’s biofuels. biofuels task force

GEORGIA MAGAZINE • MARCH 2008 33

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Artist December 2020Dokument74 SeitenThe Artist December 2020alftoy100% (2)

- HA Plug-And-Play Car Harness InstallationDokument32 SeitenHA Plug-And-Play Car Harness InstallationalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Changing Gut Microbiome May Predict How Well You AgeDokument3 SeitenA Changing Gut Microbiome May Predict How Well You AgealftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rethinking Mental HealthDokument4 SeitenRethinking Mental Healthalftoy100% (1)

- WSJ CancerDokument1 SeiteWSJ CanceralftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mind Altering MovesDokument5 SeitenMind Altering MovesalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dilution Ratio ChartDokument1 SeiteDilution Ratio ChartalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DWC - Weld - Plugs Recep - Layout 1Dokument2 SeitenDWC - Weld - Plugs Recep - Layout 1alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artists - Down.under - Dec2020 CCDokument110 SeitenArtists - Down.under - Dec2020 CCalftoy100% (1)

- Toyota Batteries - Group.24.35Dokument2 SeitenToyota Batteries - Group.24.35alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bill of Sale/Letter of Gift: WWW - Sgi.sk - Ca WWW - Finance.gov - Sk.caDokument1 SeiteBill of Sale/Letter of Gift: WWW - Sgi.sk - Ca WWW - Finance.gov - Sk.canedian_2006Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ridgid TS3650.ManualDokument52 SeitenRidgid TS3650.ManualalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Artist November 2020Dokument72 SeitenThe Artist November 2020alftoy100% (2)

- Why Did The Mallard Cross The Country? Cross The Country?Dokument4 SeitenWhy Did The Mallard Cross The Country? Cross The Country?alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effortless Action ReviewDokument22 SeitenEffortless Action ReviewalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Installation Instructions W10185365 RevADokument20 SeitenInstallation Instructions W10185365 RevAalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pernos EquivalenciasDokument2 SeitenPernos EquivalenciasEnriqueGDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agri Supply Sept 2017Dokument68 SeitenAgri Supply Sept 2017alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- OMM145182 60 Inch Mid-MountDokument32 SeitenOMM145182 60 Inch Mid-MountalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plus Center: Recommended 37° Flared Fitting Assembly Instructions JIC 37° Thread Identification & TorqueDokument2 SeitenPlus Center: Recommended 37° Flared Fitting Assembly Instructions JIC 37° Thread Identification & TorqueSantiago Escobar-KoehlerNoch keine Bewertungen

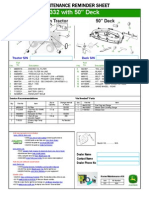

- FB MaintSheet 332 50deckLawnTractorDokument1 SeiteFB MaintSheet 332 50deckLawnTractoralftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Installation Instructions Fuse Block & Switch Panel KitDokument1 SeiteInstallation Instructions Fuse Block & Switch Panel KitalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- SL Trailers 2014 - PricingDokument17 SeitenSL Trailers 2014 - PricingalftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2006 Prius Maintenance GuideDokument24 Seiten2006 Prius Maintenance GuidealftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Guide To Shameless HappinessDokument33 SeitenA Guide To Shameless Happinessalftoy100% (1)

- Effortless Evolution Book MainDokument30 SeitenEffortless Evolution Book Mainalftoy100% (1)

- Motivation Reinforcement Support and Accountability: Real Behavior Change: What Does It Take To Break A Habit?Dokument5 SeitenMotivation Reinforcement Support and Accountability: Real Behavior Change: What Does It Take To Break A Habit?alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Veg Times Farmer Market FavsDokument21 SeitenVeg Times Farmer Market Favsalftoy100% (1)

- ClearVue Installation Instructions 2007Dokument25 SeitenClearVue Installation Instructions 2007alftoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Russian Involvement in Eastern Europe's Petroleum Industry - The Case of Bulgaria 2005Dokument41 SeitenRussian Involvement in Eastern Europe's Petroleum Industry - The Case of Bulgaria 2005stephenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dwelling PresentationDokument1 SeiteDwelling PresentationAliciaB2Noch keine Bewertungen

- 270 Boiler Control - One Modulating Boiler and DHWDokument24 Seiten270 Boiler Control - One Modulating Boiler and DHWe-ComfortUSANoch keine Bewertungen

- Station Area Planning Guide October 2017 PDFDokument116 SeitenStation Area Planning Guide October 2017 PDFAnonymous EnrdqTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basics of Automobiles: EmmisionDokument76 SeitenBasics of Automobiles: EmmisionRavindra Joshi100% (1)

- Mecanismos de CristalizaciónDokument11 SeitenMecanismos de CristalizaciónFélix AlorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power System Stability Vol II KimbarkDokument296 SeitenPower System Stability Vol II KimbarkShashidhar Kasthala100% (11)

- Performance Curve: 2 PUMPS-60HZDokument1 SeitePerformance Curve: 2 PUMPS-60HZWael BadriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arctic Cat Snowmobile Service Repair Manual 1999-2000Dokument643 SeitenArctic Cat Snowmobile Service Repair Manual 1999-2000Steven Antonio100% (5)

- Omnicomm LLS 4 Fuel Level Sensors: User Manual 18.12.2018Dokument20 SeitenOmnicomm LLS 4 Fuel Level Sensors: User Manual 18.12.2018Giovanni QuinteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- 844K 4WD Loader PIN 1DW844K D642008 Replacement Parts GuideDokument3 Seiten844K 4WD Loader PIN 1DW844K D642008 Replacement Parts GuideNelson Andrade VelasquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Level Physics Units & SymbolDokument3 SeitenA Level Physics Units & SymbolXian Cong KoayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spare Parts List STORM 15 20180000 XDokument4 SeitenSpare Parts List STORM 15 20180000 XFati ZoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application of Le Chatelier's PrincipleDokument7 SeitenApplication of Le Chatelier's PrincipleMinahil ShafiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - LAGEN - Page I - XIIDokument13 Seiten1 - LAGEN - Page I - XIISumantri HatmokoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MGG155N2: Gaseous Generator Parts ManualDokument94 SeitenMGG155N2: Gaseous Generator Parts ManualYAKOVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual 45001-2018Dokument34 SeitenManual 45001-2018Mohamed HabibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrochemistry, PPT 3Dokument33 SeitenElectrochemistry, PPT 3Ernest Nana Yaw AggreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydraulic Cylinder - Tie Rod DesignDokument8 SeitenHydraulic Cylinder - Tie Rod DesignLe Van TamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bca SyllabusDokument55 SeitenBca Syllabusapi-349492533Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pulley Systems Printed Handout - HeilmanDokument46 SeitenPulley Systems Printed Handout - HeilmanGerman ToledoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activated Carbon Literature Review-FinalDokument119 SeitenActivated Carbon Literature Review-FinalLuis VilchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Model C-30Hdz: Operations & Parts ManualDokument106 SeitenModel C-30Hdz: Operations & Parts ManualGerardo MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SerieAK-2020 GBDokument120 SeitenSerieAK-2020 GBAndré SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Megger - The Complete Guide To Electrical Insulation TestingDokument24 SeitenMegger - The Complete Guide To Electrical Insulation TestingMan Minh SangNoch keine Bewertungen

- LMP NodalBasics 2004jan14Dokument61 SeitenLMP NodalBasics 2004jan14Dzikri HakamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Completion Fluids Displacement and Cementing SpacersDokument18 SeitenCompletion Fluids Displacement and Cementing SpacersAnonymous JMuM0E5YONoch keine Bewertungen

- An Experimental Study On Usage of Hollow Glass Spheres (HGS) For Reducing Mud Density in Geothermal DrillingDokument7 SeitenAn Experimental Study On Usage of Hollow Glass Spheres (HGS) For Reducing Mud Density in Geothermal DrillingifebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sheet 1 Solution SPC 307Dokument15 SeitenSheet 1 Solution SPC 307Ercan Umut DanışanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viscosity of Blueberry and Raspberry Juices For Processing ApplicationsDokument8 SeitenViscosity of Blueberry and Raspberry Juices For Processing ApplicationsAmparitoxNoch keine Bewertungen