Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Principles of Bioethics

Hochgeladen von

banyenye25Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Principles of Bioethics

Hochgeladen von

banyenye25Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Principles of Bioethics The place of principles in bioethics In the realm of health care it is difficult to hold rules or principles that

are absolute. This is due to the many variables that exist in the context of clinical cases as well as the fact that in health care there are several principles that seem to be applicable in many situations. Even though they are not considered absolute, these rules and principles serve as powerful action guides in clinical medicine. Over the years, these moral principles have won a general acceptance as applicable in the moral analysis of ethical issues in medicine. How do principles "apply" to a certain case? Principles in current usage in health care ethics seem to be of self-evident value. For example, the notion that the physician "ought not to harm" any patient appears to be convincing to rational persons. Or, the idea that the physician should develop a care plan designed to provide the most "benefit" to the patient in terms of other competing alternatives, seems self-evident. Further, before implementing the medical care plan, it is now commonly accepted that the patient must indicate a willingness to accept the proposed treatment, if the patient is cognitively capable of doing so. Finally, medical benefits should be dispensed fairly, so that people with similar needs and in similar circumstances will be treated with fairness. One might argue that we are required to take all of the above principles into account when they are applicable to the clinical case under consideration. Yet, when two or more principles apply, we may find that they are in conflict. For example, consider a patient diagnosed with an acutely infected appendix. Our medical goal should be to provide the greatest benefit to the

patient, an indication for immediate surgery. On the other hand, surgery and general anesthesia carry some small degree of risk to an otherwise healthy patient, and we are under an obligation "not to harm" the patient. Our rational calculus holds that the patient is in far greater danger from harm from a ruptured appendix if we do not act, than from the surgical procedure and anesthesia if we proceed quickly to surgery. In other words, we have a "prima facie" duty to both benefit the patient and to "avoid harming" the patient. However, in the actual situation, we must balance the demands of these principles by determining which carries more weight in the particular case. Moral philosopher W.D. Ross claims that prima facie duties are always binding unless they are in conflict with stronger or more stringent duties. A moral person's actual duty is determined by weighing and balancing all competing prima facie duties in any particular case. What are the major principles of medical ethics? The commonly accepted principles of health care ethics include: 1. 2. 3. 4. the principle of respect for autonomy, the principle of nonmaleficence, the principle of beneficence, and the principle of justice.

1. Respect for Autonomy Any notion of moral decision making assumes that rational agents are involved in making informed and voluntary decisions. In health care decisions, our respect for the autonomy of the patient would, in common parlance, mean that the patient has the capacity to act intentionally, with understanding, and without controlling influences that would mitigate against a free and voluntary act. This principle is the basis for the practice of "informed consent" in the physician/patient transaction regarding health care. (See also Informed Consent.) Illustrative Cases 2. The Principle of Nonmaleficence

The principle of nonmaleficence requires of us that we not intentionally create a needless harm or injury to the patient, either through acts of commission or omission. In common language, we consider it negligence if one imposes a careless or unreasonable risk of harm upon another. Providing a proper standard of care that avoids or minimizes the risk of harm is supported not only by our commonly held moral convictions, but by the laws of society as well. In a professional model of care one may be morally and legally blameworthy if one fails to meet the standards of due care. The legal criteria for determining negligence are as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. the professional must have a duty to the affected party the professional must breach that duty the affected party must experience a harm; and the harm must be caused by the breach of duty.

This principle affirms the need for medical competence. It is clear that medical mistakes occur, however, this principle articulates a fundamental commitment on the part of health care professionals to protect their patients from harm. Illustrative Cases 3. The Principle of Beneficence The ordinary meaning of this principle is the duty of health care providers to be of a benefit to the patient, as well as to take positive steps to prevent and to remove harm from the patient. These duties are viewed as self-evident and are widely accepted as the proper goals of medicine. These goals are applied both to individual patients, and to the good of society as a whole. For example, the good health of a particular patient is an appropriate goal of medicine, and the prevention of disease through research and the employment of vaccines is the same goal expanded to the population at large. It is sometimes held that nonmaleficence is a constant duty, that is, one ought never to harm another individual. Whereas, beneficence is a limited duty. A physician has a duty to seek the

benefit of any or all of her patients, however, the physician may also choose whom to admit into his or her practice, and does not have a strict duty to benefit patients not acknowledged in the panel. This duty becomes complex if two patients appeal for treatment at the same moment. Some criteria of urgency of need might be used, or some principle of first come first served, to decide who should be helped at the moment. Illustrative Cases 4. The Principle of Justice Justice in health care is usually defined as a form of fairness, or as Aristotle once said, "giving to each that which is his due." This implies the fair distribution of goods in society and requires that we look at the role of entitlement. The question of distributive justice also seems to hinge on the fact that some goods and services are in short supply, there is not enough to go around, thus some fair means of allocating scarce resources must be determined. It is generally held that persons who are equals should qualify for equal treatment. This is borne out in the application of Medicare, which is available to all persons over the age of 65 years. This category of persons is equal with respect to this one factor, their age, but the criteria chosen says nothing about need or other noteworthy factors about the persons in this category. In fact, our society uses a variety of factors as a criteria for distributive justice, including the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. to each person an equal share to each person according to need to each person according to effort to each person according to contribution to each person according to merit to each person according to free-market exchanges

John Rawls and others claim that many of the inequalities we experience are a result of a "natural lottery" or a "social lottery" for which the affected individual is not to blame, therefore, society ought to help even the playing field by providing

resources to help overcome the disadvantaged situation. One of the most controversial issues in modern health care is the question pertaining to "who has the right to health care?" Or, stated another way, perhaps as a society we want to be beneficent and fair and provide some decent minimum level of health care for all citizens, regardless of ability to pay.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Principles of BioethicsDokument7 SeitenPrinciples of BioethicsNuronnisah Kalinggalan PadjiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics Power PointDokument23 SeitenBioethics Power PointMark ElbenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics PPT TheoiriesDokument57 SeitenBioethics PPT TheoiriesericaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Theories: Prepared By: Regine Emerald B Dela Cruz RNDokument20 SeitenEthical Theories: Prepared By: Regine Emerald B Dela Cruz RNRegine Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To Health Ethics' What Is Ethics?Dokument32 SeitenAn Introduction To Health Ethics' What Is Ethics?Rosalyn EstandarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Square of OppositionDokument3 SeitenSquare of OppositionPaolo Galang100% (1)

- Principles Used in BioethicsDokument57 SeitenPrinciples Used in BioethicsKim TangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ncma218: BSN 2Nd Year Summer Midterm 2022: Bachelor of Science in Nursing 2YCDokument16 SeitenNcma218: BSN 2Nd Year Summer Midterm 2022: Bachelor of Science in Nursing 2YCChesca DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics PremidDokument19 SeitenBioethics Premidclar100% (1)

- Bioethics Summer 2019Dokument14 SeitenBioethics Summer 2019suba nicholasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide 8 - Transcultural Perspetives in The Nursing Care of AdultsDokument12 SeitenStudy Guide 8 - Transcultural Perspetives in The Nursing Care of AdultsTim john louie Rancudo100% (1)

- HI 271 - 02 - Bioethics in The PhilippinesDokument45 SeitenHI 271 - 02 - Bioethics in The PhilippinesTricia GervacioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Issues IVFDokument1 SeiteEthical Issues IVFBasinga OkinamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funda Lecture SG #5Dokument5 SeitenFunda Lecture SG #5Zsyd GelladugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EuthanasiaDokument4 SeitenEuthanasiaDip PerNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIOETHICS 1.02 Ethical Decision-MakingDokument5 SeitenBIOETHICS 1.02 Ethical Decision-Makingjustine_baquiranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics (Midterm) : Principle of AutonomyDokument6 SeitenBioethics (Midterm) : Principle of AutonomyRosaree Mae Pantoja100% (1)

- Basic Ethical PrinciplesDokument6 SeitenBasic Ethical PrinciplesRegine Lorenzana Mey-Ang100% (1)

- What Is A Health Care Profession?: Chapter Iv: The Calling of The Health Care ProviderDokument14 SeitenWhat Is A Health Care Profession?: Chapter Iv: The Calling of The Health Care ProviderNur SanaaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funda Lecture SG #3Dokument9 SeitenFunda Lecture SG #3Zsyd GelladugaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EuthanasiaDokument16 SeitenEuthanasiaAnonymous iG0DCOfNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical, Legal, and Economic Foundations of The Educational Process - BUGHAO, MARIA ANGELIKADokument4 SeitenEthical, Legal, and Economic Foundations of The Educational Process - BUGHAO, MARIA ANGELIKAMaria Angelika BughaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics and Moral Issues in NursingDokument9 SeitenBioethics and Moral Issues in NursingPhilip Jay BragaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Autonomy & JusticeDokument30 SeitenPrinciples of Autonomy & JusticeDr. Liza Manalo100% (1)

- Bioethical PrinciplesDokument4 SeitenBioethical PrinciplesJestoni Dulva ManiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principle of Beneficence and NonmaleficenceDokument2 SeitenPrinciple of Beneficence and NonmaleficenceNiña Therese LabraNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIOETHICS Course OutlineDokument1 SeiteBIOETHICS Course OutlineFranco Razon100% (3)

- Midterm Coverage - NCM 108 Health Care Ethics NotesDokument10 SeitenMidterm Coverage - NCM 108 Health Care Ethics NotesAudrie Allyson GabalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prelim NCM 108 Ethics RevieweeDokument6 SeitenPrelim NCM 108 Ethics RevieweepegarliezelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Death and Dying:: Principles, Issues and ConcernsDokument54 SeitenDeath and Dying:: Principles, Issues and ConcernsGalil SuicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction Nursing EthicsDokument6 SeitenIntroduction Nursing EthicsMohammad AzizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics 1Dokument45 SeitenBioethics 1Maria Visitacion100% (3)

- Prelim Bioethics Handouts.Dokument13 SeitenPrelim Bioethics Handouts.Calimlim KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Major Principles of BioethicsDokument30 SeitenMajor Principles of BioethicsIra G. Delos SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics: Bachelor of Science in NursingDokument6 SeitenBioethics: Bachelor of Science in NursingSherinne Jane Cariazo0% (1)

- Module 4 The Calling of A Healthcare ProviderDokument6 SeitenModule 4 The Calling of A Healthcare Providercoosa liquorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name: Prado, Catherine A. Year and Section: BSN III-B Module 2 Activity Ethico-Legal Considerations in Nursing ResearchDokument2 SeitenName: Prado, Catherine A. Year and Section: BSN III-B Module 2 Activity Ethico-Legal Considerations in Nursing ResearchCatherine PradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- B I 1. E H 2. I C O: Decisions and Actions Cultural EnvironmentDokument25 SeitenB I 1. E H 2. I C O: Decisions and Actions Cultural EnvironmentDefensor Pison GringgoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Principle of BioethicsDokument7 Seiten4 Principle of BioethicsSetiady DedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preliminary Exam BioethicsDokument2 SeitenPreliminary Exam BioethicsLerma PagcaliwanganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Ethical Principles..Dokument3 SeitenBasic Ethical Principles..allyssaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethical Issues On Current Reproductive Technology: in Vitro Fertilization (Ivf)Dokument13 SeitenBioethical Issues On Current Reproductive Technology: in Vitro Fertilization (Ivf)Dred Gementiza AlidonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Individual PediaDokument37 SeitenIndividual PediaLianna M. MilitanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transcultural Nursing Quiz 2Dokument2 SeitenTranscultural Nursing Quiz 2Jenny AjocNoch keine Bewertungen

- NURS800 Myra Levine Conservation Model-1Dokument12 SeitenNURS800 Myra Levine Conservation Model-1risqi wahyu100% (1)

- Ethical Schools of ThoughtDokument5 SeitenEthical Schools of ThoughtIza AltoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bioethics LectureDokument40 SeitenBioethics LecturejeshemaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 107Dokument31 SeitenNCM 107zerpthederpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Delivery Room: History Back To TopDokument4 SeitenDelivery Room: History Back To TopeskempertusNoch keine Bewertungen

- BIOETHICS 2011 TransparencyDokument12 SeitenBIOETHICS 2011 TransparencyLean RossNoch keine Bewertungen

- Variation of SyllogismDokument2 SeitenVariation of Syllogisminah_3050% (2)

- Activity 2 Answer The Following Questions: 10 Points EachDokument4 SeitenActivity 2 Answer The Following Questions: 10 Points EachArmySapphireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wallis - Section 2 - Module 1 - "End Virginity Testing" and The "End of Female Genital Mutilation"Dokument1 SeiteWallis - Section 2 - Module 1 - "End Virginity Testing" and The "End of Female Genital Mutilation"Martha Glorie Manalo WallisNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 104 - RleDokument25 SeitenNCM 104 - RleAbigael Patricia GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - Session 1 To 3Dokument11 SeitenTHEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF NURSING - Session 1 To 3Mary LimlinganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Health NursingDokument17 SeitenFamily Health NursingMIKAELLA BALUNANNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 Chapter Anti InfectiveDokument90 Seiten01 Chapter Anti InfectiveMSKCNoch keine Bewertungen

- PhilosophyDokument6 SeitenPhilosophyjamilasaeed777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of BioethicsDokument5 SeitenPrinciples of Bioethicsshadrack mungutiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patho MIDokument2 SeitenPatho MIbanyenye25100% (2)

- Pathophysiology of Congestive Heart Failure: Cardiovascular SystemDokument3 SeitenPathophysiology of Congestive Heart Failure: Cardiovascular Systembanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Virginia Henderson TheoryDokument6 SeitenVirginia Henderson Theorybanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Letter Katrina Serquiña Y Peralta September 14, 2011Dokument1 SeiteCover Letter Katrina Serquiña Y Peralta September 14, 2011banyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Laboratory Assessment CHFDokument3 SeitenLaboratory Assessment CHFbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Com Epi PaperDokument25 SeitenCom Epi Paperbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Interventions CHFDokument3 SeitenNursing Interventions CHFbanyenye25100% (1)

- NCP BurnDokument9 SeitenNCP Burnbanyenye2533% (3)

- Patho MIDokument2 SeitenPatho MIbanyenye25100% (2)

- Acute Bronchitis PathoDokument3 SeitenAcute Bronchitis Pathobanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Population Pyramid For 2010Dokument4 SeitenPhilippines Population Pyramid For 2010banyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Laws Governing Health CareDokument5 SeitenPhilippine Laws Governing Health Carebanyenye25100% (3)

- Electro Cardiograph yDokument14 SeitenElectro Cardiograph ybanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- COMPREHENSIVE NCP Impaired PMDokument2 SeitenCOMPREHENSIVE NCP Impaired PMbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- EndometriosisDokument7 SeitenEndometriosisbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- A G E - PathoDokument1 SeiteA G E - Pathoranee dianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- NURSING CARE PLAN For Myocardial InfarctionDokument13 SeitenNURSING CARE PLAN For Myocardial Infarctionbanyenye2593% (14)

- NCPDokument4 SeitenNCPbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

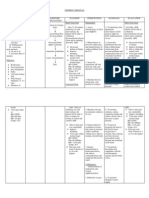

- Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Explanation Planning Nursing Intervention Rationale Evaluation SubjectiveDokument6 SeitenAssessment Nursing Diagnosis Scientific Explanation Planning Nursing Intervention Rationale Evaluation Subjectivebanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pa Tho PhysiologyDokument2 SeitenPa Tho Physiologybanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCP Risk For InfectionDokument3 SeitenNCP Risk For Infectionbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCP Risk For InfectionDokument3 SeitenNCP Risk For Infectionbanyenye25Noch keine Bewertungen

- Husky Air Compressor Operator ManualDokument60 SeitenHusky Air Compressor Operator ManualJ DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- PA1 CLASS XI P.edDokument2 SeitenPA1 CLASS XI P.edJatin GeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbDokument5 SeitenAbapi-466413302Noch keine Bewertungen

- 45764bos35945 Icitss GuidelinesDokument7 Seiten45764bos35945 Icitss GuidelinesTarun BhardwajNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELECTRICAL SAFETY in The Workplace: - Ice Breaker (Mix and Match)Dokument3 SeitenELECTRICAL SAFETY in The Workplace: - Ice Breaker (Mix and Match)Lynn ZarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forgiveness Leads To Anger ManagementDokument15 SeitenForgiveness Leads To Anger Managementjai_tutejaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHCCCS007 Learner Guide V1.1Dokument71 SeitenCHCCCS007 Learner Guide V1.1rasna kc100% (1)

- ACP-UC4Dokument11 SeitenACP-UC4FARASAN INSTITUTENoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd Quarter Examination in Hope 4Dokument5 Seiten3rd Quarter Examination in Hope 4Hazel Joan Tan100% (3)

- The Bethesda System For Reporting Cervical Cytolog PDFDokument359 SeitenThe Bethesda System For Reporting Cervical Cytolog PDFsurekhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiac RehabilitationDokument87 SeitenCardiac RehabilitationMaya Vil100% (2)

- Cyclo ThermDokument24 SeitenCyclo ThermProtantagonist91% (11)

- Test de Hormona ProlactinaDokument31 SeitenTest de Hormona ProlactinakemitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accessibility Code 2019 PDFDokument264 SeitenAccessibility Code 2019 PDFMrgsrzNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS RBD Palm Olein cp10Dokument4 SeitenMSDS RBD Palm Olein cp10sugitra sawitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admission MDS First CounsellingDokument3 SeitenAdmission MDS First CounsellingavninderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Controlling Genset NoiseDokument2 SeitenControlling Genset NoiseNishant BhavsarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pathophys BURNDokument2 SeitenPathophys BURNpaupaulala83% (6)

- People Vs Alberto MedinaDokument1 SeitePeople Vs Alberto MedinaHafsah Dmc'go100% (1)

- Pines City Colleges: College of NursingDokument1 SeitePines City Colleges: College of NursingJoy Erica LeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of Mosquito Repellent Devices-Problems and Prospects: August 2018Dokument6 SeitenUse of Mosquito Repellent Devices-Problems and Prospects: August 2018Cyrus Ian LanuriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Highlighted Word/s What Is It? Describe/DefineDokument11 SeitenHighlighted Word/s What Is It? Describe/DefineCyrus BustoneraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employers' LiabilityDokument6 SeitenEmployers' LiabilityAnjali BalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- DHCDokument2 SeitenDHCLiaqat Ali KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Etiology of Eating DisorderDokument5 SeitenEtiology of Eating DisorderCecillia Primawaty100% (1)

- c1 Mother Friendly Care NewDokument20 Seitenc1 Mother Friendly Care NewOng Teck Chong100% (1)

- Chemistry Project On Analysis of Cold DrinksDokument9 SeitenChemistry Project On Analysis of Cold DrinksKhaleelNoch keine Bewertungen

- PeadiatricDokument49 SeitenPeadiatricMARIA JAVED BSN-FA20-022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Standard RailwayDokument4 SeitenMedical Standard RailwayRK DeshmukhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge Lightspeed 16 Brochure PDFDokument8 SeitenGe Lightspeed 16 Brochure PDFJairo ManzanedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (81)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionVon EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (404)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDVon EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityVon EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (29)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeVon EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBewertung: 2 von 5 Sternen2/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsVon EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Von EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsVon EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Von EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (110)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsVon EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (3)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossVon EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (42)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessVon EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (328)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansVon EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (17)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearVon EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (23)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityVon EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisVon EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaVon EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsVon EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlVon EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (59)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceVon EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (51)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningVon EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)