Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

European History Quarterly 2012 White 706 8

Hochgeladen von

D. Silva EscobarOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

European History Quarterly 2012 White 706 8

Hochgeladen von

D. Silva EscobarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

European History Quarterly http://ehq.sagepub.

com/

Lars T. Lih, Lenin

James D. White European History Quarterly 2012 42: 706 DOI: 10.1177/0265691412458504t The online version of this article can be found at: http://ehq.sagepub.com/content/42/4/706.citation

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for European History Quarterly can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ehq.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ehq.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Oct 29, 2012 What is This?

Downloaded from ehq.sagepub.com by Daniel Silva on November 1, 2013

706

European History Quarterly 42(4)

Gerard and Burke, which, though diverse in many ways, supported the notion of a universal standard of taste. That the standard would have been found in antiquity was predetermined for elite Europeans, who had long assumed the Greco-Roman past to represent a common cultural heritage and were thus schooled in the classics. To nish their education, aristocratic Britons such as the future Dilettanti embarked on the Grand Tour and surveyed the physical remains of a world with which they had had mostly a virtual familiarity. This experience was so formative that it became the raison detre for the establishment of the Society of Dilettanti, Horace Walpole famously describing the group in 1743 as a club, for which the nominal qualication is having been in Italy, and the real one being drunk. The facetiousness of this remark aside, the rst-hand experience of antiquity on the Grand Tour may not only have catalysed the interest of members of the society in classical archaeology, but also inspired some of them to travel to the eastern Mediterranean or sponsor expeditions there. The last section of the book takes up the work of the society from 1786 to 1816, when it continued with traditional activities, such as the funding of books, and, ultimately abandoning a plan to build its own museum, lent two fragments from the Parthenon frieze to the Royal Academy and donated its inscription collection to the British Museum. During this period, one of the societys well known members, the connoisseur and scholar Richard Payne Knight, prompted scandal on two fronts, rst by the publication of his book on the Worship of Priapus, which threatened to revive the reputation of the Dilettanti as libertines, and then by denouncing the Elgin marbles as second-rate. Through its resiliency and determined sponsorship of scholarly projects, however, the Society was able to weather such storms. In addition to its other virtues, Kellys book is meticulously researched, generously illustrated, and handsomely produced. Full of nuanced ideas but historically grounded, it makes an important contribution to the study of culture and sociability and the ways in which they were related in eighteenth-century Europe. Carole Paul, University of California at Santa Barbara

Lars T. Lih, Lenin, Reaktion Books: London, 2011; 235 pp., 62 illus.; 9781861897930, 10.95 (pbk)

In this short biography of Lenin, Lih argues against what he terms the textbook interpretation of Lenins work. This holds that Lenin was worried about the workers, that he was pessimistic about their revolutionary inclinations, and consequently was inclined to give up on a genuinely mass movement. He therefore aimed instead at an elite, conspiratorial underground party staed mainly with revolutionaries from the intelligentsia. According to Lih, however, this was far from the case; Lenin was highly optimistic about the revolutionary potential of the workers. He argues that in What Is To Be Done? (WITBD) Lenin took his cue from Karl Kautskys Erfurt Programme of the German Social Democratic Party

Book Reviews

707

which propounded the idea that Social Democracy was the merger of socialism with the workers movement. Lih believes that Lenins entire outlook is to be explained not in terms of worry about the workers, but of a heroic scenario based on an enthusiastic condence that the workers would respond to the call of the Social Democrats. His heroic scenario was that the party activists would inspire the proletariat, which would carry out its historical mission by standing at the head of the entire people, leading a revolution that would overthrow the tsar and institute political freedom, thus preparing the ground for an eventual proletarian government that would bring about socialism. These are ideas that Lih expounded in his extensive commentary of Lenins WITBD, Lenin Rediscovered (2006). In the present book the author attempts to apply the concept of the heroic scenario to other major landmarks in Lenins political career. Lihs interpretation gives a mainly positive picture of Lenin, of someone who was driven by high motives and who had a deep concern for the interests of the people at large. This is an original way to look at Lenins biography and the author presents it in a fresh and highly readable fashion. Lih has unearthed a number of overlooked contemporary sources, such as William Wallings Russias Message (1908) and Gregor Alexinskys Modern Russia (1913) which he uses to good eect in placing Lenins views and activities in their historical context. The striking feature of Lihs interpretation is that it is gained at the cost of eliminating or down-playing those aspects of Lenins activities that cannot be explained in terms of the heroic scenario. Thus, although Lih mentions the fact that Lenin was involved in polemics throughout his entire political career, very little space is devoted to the feuds and in-ghting which took up so much of Lenins time and energies. In this connection Lih points out that Lenin was raised above the day-to-day squabbles by the heroic scenario through which he interpreted events (103). Because there is no detailed account of how Lenin conducted himself in these squabbles there is no chance that the reader might get the impression that Lenin could be devious, petty or treacherous qualities that might be taken to dene his character rather than his devotion to lofty ideals. Nor does the heroic scenario interpretation t particularly well any of the episodes in Lenins life with which Lih deals. An obvious example of this is when the author in mentioning Lenins writing of The Development of Capitalism in Russia in 1899 states that: In this book, lled with statistics on everything from ax-growing to the hemp-and-rope trades, he provided his heroic scenario with as strong a factual foundation as he could manage (63). Lih does not venture to demonstrate the necessary connection between Lenins statistics and the heroic scenario, and clearly it is possible to put other constructions on Lenins work. But even the existence of Lenins heroic scenario is not established by Lih, despite the length to which it had been argued in Lenin Rediscovered. One cannot say that it is a matter of either worry about the workers or the heroic scenario; the possibilities for other interpretations are by no means exhausted. For example, a reader of WITBD might well come to the conclusion that what Lenin was

708

European History Quarterly 42(4)

worried about was not the workers but the intelligentsia. If the workers were so imbued with the revolutionary spirit, what would there be left for the radical intelligentsia to do? WITBD can be regarded as providing the answer to this question and giving the intelligentsia a key role in the workers movement. Lihs book is a stimulating and challenging interpretation of Lenin as a person and a politician. It is well worth reading, especially by those who are familiar with existing works on the subject and who will be able to evaluate Lihs ideas. But if one had to recommend a biography of Lenin to someone completely unacquainted with the subject, Lihs book would not be the rst choice. James D. White, University of Glasgow

Martyn Lyons, A History of Reading and Writing in the Western World, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2009; 280 pp., 11 illus.; 9780230001619, 55.00 (hbk); 9780230001626, 19.99 (pbk)

Martyn Lyons brings decades of expertise to this elegant synthesis of scholarship on the cultural history of readers, books and reading practices. By historicizing the encounter between reader and text, while also tracing the democratization of writing practices, Lyons brilliantly connects the seemingly arcane results of book history to contemporary technological changes. He argues that the computer revolution has proved far more profound than Gutenbergs invention, in that it completely changed the material form of the codex which had been dominant for at least 1500 years. It has also invited an unprecedented involvement of the reader in the text, changing the way we write as well as the way we read (11). Twelve tightly argued chapters follow this introduction, addressing fundamental questions about the relationship between readers and texts since the codex replaced the scroll between the second and fourth centuries CE. One of the books many strengths lies in the authors ability to summarize cogently the major interpretations concerning, for example, the existence of a printing revolution, the revolutionary potential of print within early modern popular culture, the relationship of literacy to schooling, the change from intensive to extensive reading, or the characteristics of a mass reading public. Readers are introduced to the arguments of such scholars as Elizabeth Eisenstein, Robert Darnton, Roger Chartier or Rolf Engelsing, and footnotes allow one to pursue the outlined debates in more detail (a useful index oers another sort of reading). At the same time Lyonss volume makes a strong case for the theses he has defended in his previous scholarship on nineteenth-century France: the history of reading should not be reduced to a history of technological changes. Readers are inuenced by the format of what they read (large in-folios or mass paperbacks), its availability (within monastic libraries or public lending libraries), and the context in which they read (in private or in readings clubs), but such contingent factors are not sucient. The cultural history of reading that Lyons presents pays special attention to the reader as an active agent in the interpretive process, following de Certeaus famous depiction of the reader as poacher. As a result, the book

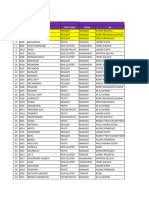

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The French Revolution and the English Novel (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Von EverandThe French Revolution and the English Novel (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Noch keine Bewertungen

- S&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressDokument23 SeitenS&S Quarterly, Inc. Guilford PressFinnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Readings in Russian Philosophical Thought: Philosophy of HistoryVon EverandReadings in Russian Philosophical Thought: Philosophy of HistoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Religion and the Rise of History: Martin Luther and the Cultural Revolution in Germany, 1760-1810Von EverandReligion and the Rise of History: Martin Luther and the Cultural Revolution in Germany, 1760-1810Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Dilemmas of Lenin: Terrorism, War, Empire, Love, RevolutionVon EverandThe Dilemmas of Lenin: Terrorism, War, Empire, Love, RevolutionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (9)

- Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance: Revised EditionVon EverandCrisis of the Early Italian Renaissance: Revised EditionBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (7)

- LENINDokument11 SeitenLENINPiyush SenapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Book of Lord Shang: Apologetics of State Power in Early ChinaVon EverandThe Book of Lord Shang: Apologetics of State Power in Early ChinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Necessary Luxuries: Books, Literature, and the Culture of Consumption in Germany, 1770–1815Von EverandNecessary Luxuries: Books, Literature, and the Culture of Consumption in Germany, 1770–1815Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prospectus of the Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln: Comprising His Speeches, Letters, State Papers and Miscellaneous WritingsVon EverandProspectus of the Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln: Comprising His Speeches, Letters, State Papers and Miscellaneous WritingsNoch keine Bewertungen

- European Socialism, Volume I: From the Industrial Revolution to the First World War and Its AftermathVon EverandEuropean Socialism, Volume I: From the Industrial Revolution to the First World War and Its AftermathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victorian Reformations: Historical Fiction and Religious Controversy, 1820-1904Von EverandVictorian Reformations: Historical Fiction and Religious Controversy, 1820-1904Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Liberty and Property: A Social History of Western Political Thought from the Renaissance to EnlightenmentVon EverandLiberty and Property: A Social History of Western Political Thought from the Renaissance to EnlightenmentBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2)

- Russ Rev Historiog-Ryan ArticleDokument40 SeitenRuss Rev Historiog-Ryan Articlemichael_babatunde100% (1)

- In Search of European Liberalisms: Concepts, Languages, IdeologiesVon EverandIn Search of European Liberalisms: Concepts, Languages, IdeologiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kevin B. Anderson - Lenin's Encounter With Hegel After Eighty YearsDokument17 SeitenKevin B. Anderson - Lenin's Encounter With Hegel After Eighty YearsAldo CamposNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ingerflom On Lih, Lenin RediscoveredDokument31 SeitenIngerflom On Lih, Lenin RediscoveredLucas Malaspina100% (1)

- BibliographyDokument33 SeitenBibliographyapi-118477065Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Waxing of the Middle Ages: Revisiting Late Medieval FranceVon EverandThe Waxing of the Middle Ages: Revisiting Late Medieval FranceCharles-Louis Morand-MétivierNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Political and Social History of Modern Europe V.1.Von EverandA Political and Social History of Modern Europe V.1.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Engels, Manchester, and The Working Class (Steven Marcus) (Z-Library)Dokument286 SeitenEngels, Manchester, and The Working Class (Steven Marcus) (Z-Library)William BlancNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolución RbakinhDokument10 SeitenEvolución RbakinhSarah ArgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder - Second EditionVon EverandThree Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder - Second EditionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- The religion of Plutarch: A pagan creed of apostolic timesVon EverandThe religion of Plutarch: A pagan creed of apostolic timesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Earthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe, from the French Revolution to the Great WarVon EverandEarthly Powers: The Clash of Religion and Politics in Europe, from the French Revolution to the Great WarBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (35)

- State of RevolutionDokument7 SeitenState of Revolutionwambua PatrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Pitt Russian East European) Evgeny Dobrenko, Galin Tihanov - A History of Russian Literary Theory and Criticism - The Soviet Age and Beyond (2011, University of Pittsburgh Press)Dokument425 Seiten(Pitt Russian East European) Evgeny Dobrenko, Galin Tihanov - A History of Russian Literary Theory and Criticism - The Soviet Age and Beyond (2011, University of Pittsburgh Press)Artur ModoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fifteen Jugglers, Five Believers: Literary Politics and the Poetics of American Social MovementsVon EverandFifteen Jugglers, Five Believers: Literary Politics and the Poetics of American Social MovementsNoch keine Bewertungen

- George Eliot and the Landscape of Time: Narrative Form and Protestant Apocalyptic HistoryVon EverandGeorge Eliot and the Landscape of Time: Narrative Form and Protestant Apocalyptic HistoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Change and Decline: Roman Literature in the Early EmpireVon EverandChange and Decline: Roman Literature in the Early EmpireNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legends That Every Child Should Know; a Selection of the Great Legends of All Times for Young PeopleVon EverandLegends That Every Child Should Know; a Selection of the Great Legends of All Times for Young PeopleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vários Autores - Lenin Reloaded Towards A Politics of TruthDokument347 SeitenVários Autores - Lenin Reloaded Towards A Politics of TruthBenjamim GomesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Tower of Elfland: The Mythopoeic Worldview of J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, and George MacDonaldVon EverandThe Great Tower of Elfland: The Mythopoeic Worldview of J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, G. K. Chesterton, and George MacDonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Stout Doctor - Martin Luthers Body - Roper PDFDokument34 SeitenThe Stout Doctor - Martin Luthers Body - Roper PDFmadspeterNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Write A HistoriographyDokument3 SeitenHow To Write A HistoriographyDouglas CamposNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914Von EverandThe Modern World-System IV: Centrist Liberalism Triumphant, 1789–1914Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Early Mathematical Manuscripts of LeibnizVon EverandThe Early Mathematical Manuscripts of LeibnizBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- A Study of The Rainbow and Women in Love: As Expressions of D. H. Lawrence’s Thinking on Modern CivilizationVon EverandA Study of The Rainbow and Women in Love: As Expressions of D. H. Lawrence’s Thinking on Modern CivilizationNoch keine Bewertungen

- BREINES. Young Lukacs, Old Lukacs, New LukacsDokument15 SeitenBREINES. Young Lukacs, Old Lukacs, New LukacsJoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Jaworskyj, Ed. - Soviet Political Thought - An Anthology (1967)Dokument633 SeitenMichael Jaworskyj, Ed. - Soviet Political Thought - An Anthology (1967)maxfrischfaberNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sleepwalking into a New World: The Emergence of Italian City Communes in the Twelfth CenturyVon EverandSleepwalking into a New World: The Emergence of Italian City Communes in the Twelfth CenturyBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Capital & Class 1993 Naples 119 37Dokument20 SeitenCapital & Class 1993 Naples 119 37D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Politics Philosophy Economics 2002 Barry 155 84Dokument31 SeitenPolitics Philosophy Economics 2002 Barry 155 84D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Origin of Surplus ValueDokument15 SeitenThe Origin of Surplus ValueD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Environmental Paradox of The Welfare State The Dynamics of SustainabilityDokument20 SeitenThe Environmental Paradox of The Welfare State The Dynamics of SustainabilityD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1996 Froud 119 34Dokument17 SeitenCapital & Class 1996 Froud 119 34D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1997 Townshend 201 3Dokument4 SeitenCapital & Class 1997 Townshend 201 3D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1995 Articles 156 8Dokument4 SeitenCapital & Class 1995 Articles 156 8D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class: The Fetishizing Subject in Marx's CapitalDokument32 SeitenCapital & Class: The Fetishizing Subject in Marx's CapitalD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2000 Went 1 10Dokument11 SeitenCapital & Class 2000 Went 1 10D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2002 Ankarloo 9 36Dokument29 SeitenCapital & Class 2002 Ankarloo 9 36D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2003 Articles 175 7Dokument4 SeitenCapital & Class 2003 Articles 175 7D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class: State Theory, Regulation, and Autopoiesis: Debates and ControversiesDokument11 SeitenCapital & Class: State Theory, Regulation, and Autopoiesis: Debates and ControversiesD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1996 Itoh 95 118Dokument25 SeitenCapital & Class 1996 Itoh 95 118D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class-2003-Yücesan-Özdemir-31-59Dokument30 SeitenCapital & Class-2003-Yücesan-Özdemir-31-59D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1997 Pakulski 192 3Dokument3 SeitenCapital & Class 1997 Pakulski 192 3D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2005 Moore 39 72Dokument35 SeitenCapital & Class 2005 Moore 39 72D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1997 Articles 151 3Dokument4 SeitenCapital & Class 1997 Articles 151 3D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class: The Crisis of Labour Relations in GermanyDokument30 SeitenCapital & Class: The Crisis of Labour Relations in GermanyD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1997 Stewart 1 7Dokument8 SeitenCapital & Class 1997 Stewart 1 7D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2000 Spence 81 110Dokument31 SeitenCapital & Class 2000 Spence 81 110D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1995 Tittenbrun 21 32Dokument13 SeitenCapital & Class 1995 Tittenbrun 21 32D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review of Radical Political Economics 2000 Matthews 470 81Dokument13 SeitenReview of Radical Political Economics 2000 Matthews 470 81D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class: Post-Structuralism 'Work-Welfare'and The Regulation of The Poor: The Pessimism ofDokument20 SeitenCapital & Class: Post-Structuralism 'Work-Welfare'and The Regulation of The Poor: The Pessimism ofD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Sociology: Lenin's Critique of Narodnik SociologyDokument5 SeitenCritical Sociology: Lenin's Critique of Narodnik SociologyD. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2003 Dinerstein 1 8Dokument9 SeitenCapital & Class 2003 Dinerstein 1 8D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Politics Philosophy Economics 2004 Mueller 59 76Dokument19 SeitenPolitics Philosophy Economics 2004 Mueller 59 76D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 1997 Articles 155 6Dokument3 SeitenCapital & Class 1997 Articles 155 6D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2001 Radice 113 26Dokument15 SeitenCapital & Class 2001 Radice 113 26D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2002 Cam 89 114Dokument27 SeitenCapital & Class 2002 Cam 89 114D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capital & Class 2000 Shorthose 191 208Dokument19 SeitenCapital & Class 2000 Shorthose 191 208D. Silva EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSC GD Constable Notification - pdf-67Dokument7 SeitenSSC GD Constable Notification - pdf-67TopRankersNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 08 2017 Chennai TH BashaDokument24 Seiten15 08 2017 Chennai TH BashaShaik Gouse BashaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Libunao V PeopleDokument29 SeitenLibunao V PeopleHannah SyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31.99.99.M2 President's Delegation of Authority For Human Resource Administration MatrixDokument11 Seiten31.99.99.M2 President's Delegation of Authority For Human Resource Administration MatrixtinmaungtheinNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLJ 1995 3 434 JLDSSMKDokument7 SeitenCLJ 1995 3 434 JLDSSMKSchanniNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIL BernasDokument655 SeitenPIL Bernasanon_13142169983% (6)

- Section 6A of The DSPE ActDokument3 SeitenSection 6A of The DSPE ActDerrick HartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic V LaoDokument2 SeitenRepublic V LaoBlastNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 Research Paper Topics - Midway CollegeDokument7 Seiten100 Research Paper Topics - Midway CollegeVishu MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vol30 No2 KatesMauseronlineDokument46 SeitenVol30 No2 KatesMauseronlineabcabc123123xyzxyxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gad Duties and ResponsibilitiesDokument1 SeiteGad Duties and ResponsibilitiesLeslie Joy Estardo Andrade100% (1)

- Pablo Leighton, Fernando Lopez (Eds.) - 40 Years Are Nothing - History and Memory of The 1973 Coups D'etat in Uruguay and CDokument144 SeitenPablo Leighton, Fernando Lopez (Eds.) - 40 Years Are Nothing - History and Memory of The 1973 Coups D'etat in Uruguay and CCatalina Fernández Carter100% (1)

- Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in The Global SouthDokument316 SeitenPostcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in The Global SouthAnja SchwarzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Government of India LAW Commission OF IndiaDokument27 SeitenGovernment of India LAW Commission OF IndiaLatest Laws TeamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mortmain ActDokument16 SeitenMortmain Actagray43100% (1)

- After Operation Oplan Kaluluwa 2012Dokument2 SeitenAfter Operation Oplan Kaluluwa 2012Rile Nyleve100% (1)

- Catalan Agreement On Research and InnovationDokument96 SeitenCatalan Agreement On Research and InnovationDr. Teresa M. TiptonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 BIR RMO No. 20-2007Dokument3 Seiten13 BIR RMO No. 20-2007Clarissa SawaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank Chapter 9Dokument10 SeitenTest Bank Chapter 9Rebecca StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Response To Superior Court and Judge Becker's Motion To DismissDokument25 SeitenResponse To Superior Court and Judge Becker's Motion To DismissJanet and JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indian History Chronology - Ancient India To Modern India - Clear IASDokument5 SeitenIndian History Chronology - Ancient India To Modern India - Clear IASRahul KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- DBPC Maths Prelims PaperDokument8 SeitenDBPC Maths Prelims PaperAyushi BhattacharyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sto. Rosario Elementary School: Annual Implementation PlanDokument31 SeitenSto. Rosario Elementary School: Annual Implementation PlanDianneGarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPM Pear Century-1Dokument22 SeitenRPM Pear Century-1rinakawuka08Noch keine Bewertungen

- CSC Form 6 2017Dokument1 SeiteCSC Form 6 2017Nard LastimosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Us Vs Toribio PDFDokument2 SeitenUs Vs Toribio PDFDebbie YrreverreNoch keine Bewertungen

- BA LunasDokument40 SeitenBA LunasAmin AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yao vs. MatelaDokument2 SeitenYao vs. MatelaDongkaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSTP - Great LeaderDokument3 SeitenNSTP - Great LeaderRy De VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Percent - Fin - e - 237 - 2013Dokument3 Seiten3 Percent - Fin - e - 237 - 2013physicspalanichamyNoch keine Bewertungen