Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Swahili Architectural Influnces

Hochgeladen von

Billy 'EnCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Swahili Architectural Influnces

Hochgeladen von

Billy 'EnCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by: [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] On: 21 July 2013,

At: 04:08 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

South Asian Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rsas20

A collection of merits: Architectural influnces in the Friday Mosque and Kazaruni Tomb Complex at Cambay, Gujarat

Elizabeth Lambourn Published online: 11 Aug 2010.

To cite this article: Elizabeth Lambourn (2001) A collection of merits: Architectural influnces in the Friday Mosque and Kazaruni Tomb Complex at Cambay, Gujarat, South Asian Studies, 17:1, 117-149, DOI: 10.1080/02666030.2001.9628596 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2001.9628596

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http:// www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

"A collection of merits../': 1 Architectural influnces in the Friday Mosque and Kazaruni Tomb Complex at Cambay, Gujarat

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

"Cambay is one of the most beautiful cities as regards the artistic architecture of its houses and the construction of its mosques. The reason is that the majority of its inhabitants are foreign merchants, who continually build theie beautiful houses and wonderful mosques - an achievement in which they endeavour to surpass each other." Ibn Battuta, ca. 743/3422

Chitlorgarh

I. Map of western India with the principal sites mentioned.

Tughluq architecture has justly been described by Anthony Welch and Howard Crane as "a turning point in the history of India's Islamic architecture" (Welch & Crane, 1983, p. 123). Thanks to the efforts of these, and other, scholars Tughluq architecture is becoming ever better known and the last twenty years have seen substantial advances in the documentation of new structures and in the analysis of Tughluq building types and patronage. Much attention has obviously focused on the Tughluq architecture that survives at Delhi, the capital, but a large number of structures still remain to be

studied in the provinces of the Tughluq empire. The study of these "provincial" monuments is obviously important for completing our picture of Tughluq architecture and patronage, and understanding the extent to which Tughluq forms were disseminated in the rest of the Empire and adapted to local styles and conditions. Moreover, in many cases these monuments also represent the foundations of the later regional styles of Islamic architecture that grew up after the collapse of the Tughluq Empire at the end of the 14th century. In the changed political context of the 15th century, these

117

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

.

i . . .

a m

I *_^-^|_

* m

i aak ?5

JiJLwV *

ft ft "ft ft

ft ft

a a a a a

a . a a

. .. . .-

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

&3

u

. . - .

M R U a a ,_i

ft ft a a a a

M M

"

-Id

'

'

I 1

]

a ft a a

a a * a a a ft .*

a a

a m a N a M a a

* *

Jsfc

l a M m m 1 | . . .

N a

a a P

I

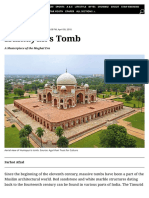

Ground plan of the Friday mosque and Kazaruni tomb complex, Cambay. Gujarat. (From Burgess, 1896.)

ft

ft

ft

ft a *

a a

Tf

View of the Friday mosque and Kazaruni tomb complex at Cambay, from the east.

structures are no longer provincial reflections of a distant capital but central models for the architecture of the new independent Sultanates. The State of Gujarat in western India preserves a large group of Tughluq structures, principally large congregational, or Friday, mosques, built in the years following the Muslim conquest of the region in 704/1304-05 under the Khaljis.3 Many of these structures are still unknown, documented only through Archaeological Survey of India volumes, and practically all would merit fuller publication. 4 This article focuses on two of the earliest, most innovative, complex and influential buildings in this group: the 725/1325 Friday mosque at the port of Cambay and the tomb complex of

\Jmar al-Kazaruni (d. 734/1333) to its south. The Friday mosque and Kazaruni tomb complex would undoubtedly be ranked as exceptional structures whatever their place or period. Their monumentality, imagination and the sheer skill of their construction and decoration place them alongside some of the finest buildings in the Islamic world and for this alone a fresh publication is long overdue. The two structures are also exceptional for the breadth of sources they gather together, a breadth that reflects Cambay's position at the interface between Sultanate northern India and the western Indian Ocean. Perhaps as a consequence of this many elements, especially those of the tomb complex, are innovative and technically experimental. All these qualities helped to

118

South Asian Studies 7

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

""HSMF

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

4.

View of the prayer hall facade, Friday mosque, Cambay, including the small chattri at the centre of the courtyard. (Courtesy of the AIIS, Centre for A r t and Archaeology, New Delhi.)

often treated them as a single structure, referring to both either as a tomb or as a mosque. The pattern of their subsequent influence within Gujarat also suggests that they were seen as a single complex by the local Muslim communities.

PARTI THE STRUCTURES Since the Friday mosque and Kazaruni tomb complex have not been published substantially since 1896, when they were documented by James Burgess,4 this article begins with a more extensive description and a reconstruction of the two structures. THE FRIDAY MOSQUE AND ITS PATRON The Friday mosque The Friday mosque is a hypostyle or Arab plan mosque, consisting of a central courtyard surrounded by the main prayer hall on the west side and colonnades on the remaining three sides (Fig. 2). The mosque is an imposing structure measuring approximately 64.5 by 60 meters, or 212 by 197 feet, externally. In a sophisticated and inspired compositional touch, the centre of the mosque courtyard is marked by a small ornately carved chattri or pavilion (Fig. 4). Construction throughout the mosque is entirely in stone and mainly trabeate, employing corbelled domes and arches. Practically all the stone employed in the mosque must have come from Cambay's Jain and Hindu temples but this spolia is generally reused discreetly.

5.

View of the north east entrance, Friday mosque, Cambay. with the 725/1325 foundation inscription and traces of the pilasters of the original porch.

establish the Friday mosque and Kazaruni tomb complex at Cambay as fundamental models for the later architecture of the Sultans of Gujarat during the 15th and 16th centuries. This said, the complexity of each structure, and of their relationship to each other, makes their discussion long and difficult. On the one hand, they are two distinct structures in terms of their function, phases of construction, patrons and architectural sources, and so might be discussed in separate articles. On the other hand, they are physically interlinked to the extent that it is impossible to discuss one without the other. Not only do the two buildings share many constructional and stylistic details but the tomb complex is built against the entire length of the mosque's south wall, and the two are linked internally by numerous windows and connecting doorways (Figs. 2 & 3). The final effect is of a single complex and indeed Western travellers - who provide our only early descriptions of these two buildings - have

119

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

6.

View of the interior of the sanctuary, Friday mosque. Cambay, showing the use of grey stone for the pillars around the central mihrab.

7.

View of the south-western muluk khanah, Friday mosque, Cambay.

An inscription over the northern entrance of the mosque records its foundation on 18 Mulmrram 725, equivalent to 4 January 1325, under the patronage of Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari (Fig. 5). The full text of the inscription runs as follows (translation from Mahdi Husain's edition of the inscription). 6

^ j J u l j u v - . U ^ ^ I U t J U j I ^ . I il\p\j*Ji1*Jl J J U I J - U - I jj; t _llU c y ; *iU1j.all li ii,lf U ^UJIjlULJl J i t y i j u ;

LLJJJ jLru iiHtjJA

*-& jfrJt&JA fcAI^U-J

AJIJ^-O)

J l l l i -.LUi^i^iui

4 lILJLi.*-/j4LiJj*lJl*:iUJL. u e)b- 1> .ili'jiA ; -#;*;jUj(T)

j f l j j l JLJ^S\ JUJI *;LUL. } SL M M- jlUuJI l U l U : .Li JLJJ JSLJI

^ U > _ - j l > C r l * 1 J J - i L . r j * ! l ^ ^ i i l > . L U I t > a ) i J * < l ^ i l >*JjWjt* JUrf

(Line 1) In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. And the places of worship are for Allah alone so invoke no-one else besides Allah.7 And the Prophet, peace be upon him, says "Whoever builds a mosque for Allah, even though it be as small as the dwelling of a partridge, Allah will build for him a house in paradise". 8 This is by one who has been rightly guided and helped by Him. This blessed Friday mosque and its building were constructed (Line 2) wholly and completely, out of his own money from what Allah had given him through His grace and benevolence, merely for the sake of Allah the Exalted, during the reign of the learned and just Sultan Muhammad Shah son of Tughluq Shah the Sultan - may Allah perpetuate his dominion and power - by the weak creature, expectant of the mercy of Allah the Exalted, Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari 9 , may Allah enable him to achieve his object. And that took place on the eighteenth of Mulmrram in the year seven hundred and twenty five.10 The main prayer hall has a relatively simple internal articulation of fourteen large domes of equal size and height, with a raised and screened prayer area or muluk khanah, literally "king's chamber", at either end

(Fig. 7). The precise uses of muluk khanahs in India have yet to be fully explored and they are often referred to as women's galleries. However, one of the earliest explanations of this feature appears in the memoirs of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir on the occasion of a visit to the Friday Mosque at Ahmedabad where he explains that these shall nishin, called muluk khanah in Gujarat, were built to shield the King when he attended Friday or 'Id prayers "on account of the crowding of the people" (Jahangir, 1909-14, p. 425). This explanation suggests that they were in fact maqsurahs. The mosque has a total of five mihrabs, three principal mihrabs in the main prayer hall and two simpler mihrabs in each of the muluk khanahs (Fig. 8). Tine three principal mihrabs are also "reflected" on the exterior of the qiblah wall, marked by three projecting semi-circular buttresses (Fig. 9). As befits a jami' or congregational mosque it is provided with a minbar or pulpit for the delivery of the khutbah or sermon on Fridays and other important days situated just to the north of the central mihrab and built like this entirely in white marble (Fig. 10). n Probably the most distinctive feature of the mosque is the solid masonry screen with arched openings that is built across the fagade of the prayer hall, effectively masking its trabeate construction. A number of arched openings within the screen allow a glimpse of the hall behind, and the central arch is emphasised by being wider and higher than its neighbours (Figs. 4). The mosque is not provided with a tower minaret, instead stairways within the fagade screen give access to the roof of the mosque from where the call to prayer would have been made. The mosque has a total of five entrances, one on the east, on axis with the centre of the qiblali wall (Fig. 3) and two entrances each on the north and south sides, one permitting access directly into the prayer hall of the mosque, just beneath the muluk khanahs (Fig. 11), the other leading straight into the courtyard. The principal

120

Smith Asian Studies 37

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS.

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

Above: 8. Small marble mihrab in the north-western muluk khanah, Friday mosque. Cambay. Top right: 9. The back of the qiblah wall of the Friday mosque, Cambay, showing the use of different coloured stones in the construction of the mihrab projections. Below 10. View of the unfinished or restored marble minbar, Friday mosque, Cambay.

mm

121

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

*)

*- **"'*

r,-*S

***

*

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

11. North-western entrance to the prayer hall of the Friday mosque, Cambay.

entrance appears to have been the north-eastern one, that which leads into the mosque courtyard on the northern side (Fig. 5). This entrance is more heavily carved than the other four and traces of four pilasters on the exterior wall suggest that it was originally fronted by a large porch. The wear on its threshold amply demonstrates its use over time. 12 However, it appears to have suffered considerably, the entire wall and the dome behind show evidence of rebuilding or repair. The Friday mosque is built in a yellow or pinkish sandstone but its major axes and focal areas are cleverly emphasised by polychrome stonework. Thus the five mihrnbs and the minbar are carved in a mixture of white marble and a grey-green slate-like stone, and the entire bay in front of the central mihrab is defined by pillars carved in this grey-green stone which contrast with the yellow-pink stone of the other supports (Fig. 6). According to a comment by the British official James Forbes who visited the mosque in the early 1770s, it seems that the mosque and courtyard were originally paved with white marble (Forbes, 1834, p. 319). The chattri at the centre of the courtyard introduces new types and colours of stone; its four pillars are carved in a yellow stone whilst its floor still preserves an intarsia decoration of white, black and yellow marbles. 13 This polychromy also extends to the exterior of the building. The three projecting buttresses on the exterior of the qiblah wall are faced with the same mixture of grey slate and white marble as the interior (Fig. 9). The two principal entrances on the north side both have white marble frames and thresholds whilst the important foundation inscription over the north-east entrance is

carved in fine creamy white marble (Figs. 5 & 11). The white marble and grey slate pilasters that have survived around this entrance - all that remains of its entrance porch - further suggest that this structure was also built from a variety of coloured stones. The design and decoration of many elements throughout the mosque - notably the doorways, the columns, and the exterior mouldings - are all based in the local Gujarati vocabulary of decoration. Whilst certain elements such as ceilings have been identified as spolia from earlier temples (Fig. 12), this material appears to have been carefully selected and non-figural to begin with, for there are none of the hacked or mutilated images seen in early mosques such as the Quwwat alIslam mosque in Delhi or the Ajmer mosque. 14 Many other elements appear to have been purposely carved for the mosque, using local types but omitting figural imagery, nevertheless, the whole process and balance of spoliated and recarved material would repay further attention. There is no doubt that the mosque has undergone substantial reparations over time but these have generally been executed with sensitivity and have sought, as far as possible, to blend the new with the old. The city of Cambay has faced so many upheavals that it is impossible to chart the building's complete history. As far as we can tell the mosque was in continuous use, an inscription in the courtyard certainly records that the hawd or reservoir was repaired in 1030/1620-21 (ARIE, 1956-57, D 44) and when Pietro della Valle visited Cambay only a few years later in 1623 he described a much frequented "Meschita" or mosque near the sea-

122

South Asian Studies 7

"ACOLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

12. Early 13th century corbelled dome reused in the Friday mosque. Cambay. (Courtesy of the AIIS. Centre for A r t and Archaeology, New Delhi.)

side which appears to correspond to our Tughluq mosque. Delia Valle describes "a Meschita, or Temple of the Mahometans, whereunto there is continually a great concourse of people with ridiculous and foolish devotions, not merely Mahometans but likewise Gentiles [Hindus]. In the street before the Gate many persons sitting on the ground asked Alms, to whom the passersby cast, some Rice, others certain other corn, but no Money" (della Valle, 1892, p. 69).15 Although the mosque appears to have fallen into disrepair by the later 17th century - since de Thevenot noted that the "sepulchre" (meaning both the Friday mosque and tomb complex) was "kept in bad repair" when he visited Cambay in 1667-68 (de Thevenot, 1949, p. 18) - there is no reason to suppose that it ceased to be used. At some stage before the late 18th century the white marble paving of the mosque was also removed (Forbes, 1834, p. 319). It also seems probable that the mosque suffered some structural damage during the great earthquake that shook Gujarat and Kutch in 1819 (Summers, 1854, p. 21) and substantially damaged the Kazaruni complex. The damage to the north entrance may date to this time (Fig. 5), as well as that to the cusped arch that is inserted within the central arch of the prayer hall faade, apparently to support the clerestory jalis (Fig. 4). A description of the mosque in the mid-19th century, though heavy with romantic overtones, confirms its extreme dilapidation: "the exterior exhibits palpable evidence of rapid annihilation; and the decaying colonnades, the injured arches - indeed every indication of age and ruin are quite unmistakable with the interior" (Briggs, 1849, pp. 161-62). However, it

appears to have continued in use into the late 19th century since a second inscription near the mosque's water tank mentions the "construction of the cistern with a roof carried out through the efforts of the local Muslims" in 1297/1879-80 (AR1E, 1956-57, D 43).16 Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari Thanks to the research of Mahdi Husain, the Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari of the foundation inscription has been identified with a certain Dawlatshah Muhammad or Malik Dawlatshah mentioned in contemporary histories as one of the main amirs of the Tughluq period (Mahdi Husain, 1957-58, pp. 29-34). 'Isami records that he served on the military expedition of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq to Lakhnauti (c. 1324) and also served Muhammad bin Tughluq Shah during the Multan expedition of 730/1330-31, where he commanded the right wing during the battle of Abohar (Mahdi Husain, 1957-58, p. 30). According to Barani at this time Dawlatshah Muhammad held the post of Aklwr Bek or Superintendent of the Royal Stable. Thanks to Ibn Battuta we know that Dawlatshah Muhammad died during Muhammad bin Tughluq's campaign in Malabar, succumbing to the plague in Telingana in 735/1335 (Mahdi Husain, 1957-58, p. 30). Although none of these sources give Dawlatshah Muhammad's nisbah,17 alButihari, or mention any particular involvement with Gujarat, Mahdi Husain's identification appears to be correct since the names and dates of the two characters correspond closely. Although contemporary sources do not mention

123

I I ,/'. I I I I A M B O U K N

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

13. View of the interior of al-Kazaruni's mausoleum with his cenotaph, facing towards the south doorway, Kazaruni complex, Cambay.

Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari's involvement in Gujarat, a number of surviving inscriptions indicate that he had strong links with the ports of Gujarat during the 1320s. Al-Butihari is mentioned in three other inscriptions from the nearby port of Bharuch: his name appears in the foundation inscription of the Friday mosque at Bharuch, dated 721/1321, in another mosque foundation inscription of 722/1322, 18 and finally on the foundation inscription of the port's namaz garh (an open area for communal prayer on special occasions in the Muslim calendar) which is dated 726/1326.1M Unfortunately, the first two inscriptions are so badly damaged that we cannot specify the role he played in these projects. He may have been the main patron of these buildings or his name may feature in these inscriptions simply because he held an official post in Gujarat and it was customary to include the names of important local officials in such inscriptions. The important point is that he was already in Gujarat at this period and apparently in an official capacity. Fortunately, the third inscription on the minbar or pulpit of the namaz garh at Bharuch is complete. It records al-Butihari's patronage of the structure in 726/1326 - only a year after the Friday mosque at Cambay - and paid for once again out of his personal funds. The mention of al-Butihari's name in four inscriptions from these two sites - in two cases as the patron of major religious structures demonstrates that he had close, and very probably official, ties to the ports of western India.

The existence of these inscriptions in no way invalidates the identification made by Mahdi Husain. 14th century histories do not pretend to the kind of biographical detail found, for example, in Mughal biographical dictionaries, their failure to mention Dawlatshah Muhammad's career in Gujarat is therefore not proof that he was never posted there. Equally, and for reasons that have yet to be explained, the nisbah (al-)Butihari may only have been used or known in Gujarat. Indeed, in some cases, details from the inscriptions and texts actually reinforce one another. The namaz garh inscription furnishes new official titles which appear to confirm Dawlatshah Muhammad's involvement in the Lakhnauti campaign as mentioned by c Isami. In this text al-Butihari is referred to as Malik alSharq Fakhr al-Dawlah wa al-Din Dawlatshah Muhammad Butihari, literally, King of the East, Pride of the State and Religion, Dawlatshah Muhammad Butihari. One may wonder whether the new title Malik al-Sharq or King of the East was awarded as a result of Dawlatshah Muhammad's participation in the Lakhnauti campaign. One detail of Dawlatshah Muhammad's career may provide a clue to his posting in the ports of Gujarat. Barani mentions the fact that Dawlatshah Muhammad held the post of Akhur Bek or Superintendent of the Royal Stable around 1330 and this information suggests that he may have had a particularly good knowledge of horses. As Simon Digby's study on war horses and elephants in India has shown, India imported large numbers of

124

South Asian Studies 17

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

14. View of the main, south facade of the Kazaruni complex showing the entrance portal or pishtaq.

horses to serve in the cavalry. Many were imported by sea from the Persian Gulf, Arabian Peninsula and Iran, and landed at the western seaports (Digby, 1971 p. 1). A related phenomenon, that has received far less attention, is the appointment of well-connected horse merchants as officials in the ports or states which imported these horses. Probably the best known example is the connections between the Pandyan rulers of Madurai and the al-Tibi merchant family who ruled the coasts of Fars and its islands during the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The Pandya imported almost 1,500 horses annually from the Tibis alone and for several decades, until the Khalji conquest of Ma'bar, members of the Tibi family were appointed as viziers to the Pandyas and as governors of their three main ports (Aubin, 1953, pp. 8999; Shokoohy, 1991, p. 32). Although data is lacking for western India during the Tughluq period, we know that in the Mughal period horse traders were quite often appointed to administer or govern ports there, exploiting their connections and their expertise in horses. In 1056/1646, for example, the Iranian merchant and horse trader cAli Akbar Isfahani was appointed by Shah Jahan to administer the ports of Surat and Cambay on the basis that "since [he] is a merchant and has knowledge of judging horses and jewels, it is possible that he will be able to administer ports in an efficient manner" (Khan, 1965, p. 196).20 The logic of this system suggests that it may well have been in place long before the Mughal period and we might speculate that, whilst Dawlatshah Muhammad's military career makes it unlikely that he was himself a horse merchant, he may well have been appointed to Bharuch and Cambay in connection with the procurement of horses for the Tughluq Sultans. THE KAZARUNI TOMB COMPLEX The Friday mosque cannot be discussed independently from the tomb complex that flanks its entire southern side (Figs. 2 & 3). The two cenotaphs of c Umar al-

15. View of the main entrance portal or pishtaq, south facade of the Kazaruni complex. (Courtesy of the AIIS, Centre for A r t and Archaeology, New Delhi.)

Kazaruni (d. 734/1333) and his wife Bibi Fatimah (d. 784/1382) at the centre of the complex are among the best published Islamic monuments at Cambay 21 yet the complex that houses them has never been fully studied. Al-Kazaruni's grave is usually referred to as being situated in his mausoleum, but this is only the central part of a tripartite complex comprising a separate multifunctional structure - definitely in part a mosque to the west, and a large courtyard area on the east. The mausoleum and pishtaq The largest element of the tomb complex is the mausoleum that houses the graves of c Umar al-Kazaruni and his wife (Fig. 13). This mausoleum is a large and complex structure, measuring approximately 15,5 metres, or 51 feet, at its widest (east to west), and conceived on three or perhaps even four storeys. At floor-level are the two cenotaphs set within an octagonal mausoleum, with a first floor gallery or above this from which one can look down onto the cenotaphs below and out over the surrounding landscape. A low solid railing marks the outer edge of the gallery (Fig. 13). This mausoleum is fronted on the south by a large portal, in Persian pishtaq (Figs. 14 & 15). Pishtaq literally means "the arch in front," and the portal consists of a large

125

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

rectangular front, raised above the level of the surrounding walls and structures, and with a deep arch at its centre. Steps from street level lead up and back to the actual doorway to the mausoleum. The dome and its portal are perfectly integrated with a small loggia or balcony in the upper half of the portal that both continues the gallery level of the mausoleum and affords a view out over the port area and the Gulf of Cambay (Figs. 15 & 16). Tucked within the massive sides of the portal are two spiral staircases that lead from ground level up to the first floor gallery and then up again to the roof level of the pishtaq (Figs. 2 & 17). The whole structure of the Friday mosque and the tomb complex sit upon a high masonry plinth that varies in height between one and two meters. It is highest on the southern and western sides of the complex and it seems likely that the Kazaruni burial crypt lies here, exactly beneath the floor-level cenotaphs that indicate the burial spot.22 This crypt would constitute the fourth storey of the mausoleum. The mausoleum was originally covered by a dome, but "in June 1819, the largest and loftiest dome, under which the remains of the founder are entombed, was thrown down by a severe shock of an earthquake, the same which caused the devastations in Cutch, and throughout Gujarat" (Summers, 1854, p. 21) (Fig. 18). The quantity of stone rubble at the site certainly seems to confirm that the dome was of stone. The extra pillars added to buttress the unsupported western and eastern sides of the octagon also indicate worries about the lateral thrust of an unusually large and very heavy dome. The inner diameter of the octagon is just under 12 m (39 ft), and there seems little doubt that, at the period

Above

16. View of the interior of the balcony within the pishtaq, Kazaruni complex.

Below 17. View of the juncture of the mausoleum and pishtaq from the east courtyard, and showing the doorways giving access to the staircases within each wing of the pishtaq, Kazaruni complex.

126

South Asian Studies 17

A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

n^gmiunntv

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

18. View of the lost dome, mausoleum, Kazaruni complex.

of its construction, the stone dome over al-Kazaruni's mausoleum was the largest ever built in western India. By contrast, the domes in the adjacent Friday mosque all measure approximately 5.5 m (18 ft) in diameter, an average size for domes in the 14th century Islamic architecture of western India. Stone domes of this diameter appeared only in the mid-15th century, as in the mausoleum of Ahmad Shah I at Ahmedabad and in that of Shaykh Ahmad Khatu at Sarkhej, but even in these instances they cover single-storey structures and are solidly buttressed by a crown of smaller domes. 23 AlKazaruni's mausoleum was a truly experimental structure, worthy of the architectural rivalry described by Ibn Battuta.

The paired minarets The dome of al-Kazaruni's mausoleum is not the only part of this complex to have been lost through natural disasters. A description of the Friday mosque and tomb complex by James Forbes at the end of the 18th century mentions that "over the south entrance of the tomb complex was a handsome minaret; its companion having been destroyed by lightning, was never replaced" (Forbes, 1813, vol. II, p. 17). The accuracy of Forbes' remark is borne out by an accompanying panoramic sketch, drawn in 1772, which shows the southern face of the Kazaruni tomb complex with its domed mausoleum and the surviving eastern minaret above the pishtaq (Fig. 19).24 The

19. View of Cambay, from the south, showing one of the two original minarets atop the tomb complex's entrance gateway. Engraved by J. Shury from an original sketch by James Forbes in 1772 AD. (From Forbes, 1834) (Photograph Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art. New Haven.)

127

ELIZABETII LAMBOURN

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

20. View of the western portion of the Kazaruni complex, from the courtyard of the tomb complex.

21. Exterior view of the western portion of the Kazaruni complex, a multi-functional area including a small mosque.

22. Mihrab in the western portion of the Kazaruni complex. (Courtesy of the AIIS, Centre for A r t and Archaeology, New Delhi.)

height " near the sea-shore at Cambay which seems to correspond to the surviving minaret (Finch, 1921, p. 174). The remaining minaret must have collapsed, along with the mausoleum dome, in the 1819 earthquake. It is difficult to know how far to trust Forbes' sketch for a reconstruction of the minarets, since they are only details in a panoramic view. Nevertheless, they appear to have been circular and the two balconies indicated in the sketch suggest that they had internal staircases that continued from the circular staircase within each wing of the pishtaq. The presence of these minarets explains the extraordinary thickness of the portal's walls, but most importantly indicates that the pair of minarets were part of the original design of the complex rather than a later addition. As far as can be judged from the sketch they were substantial structures, and at least doubled the height of the pishtaq, which would suggest a height of at least 12m (40 ft) from roof level. Forbes' sketch gives no idea of the material used to construct these two minarets. Stone is a strong possibility (the later 15th century minarets of Ahmedabad are of stone) and might explain the extreme thickness of the pishtaq's walls. However, the abundance of brick construction in the central plain of Gujarat means that we cannot rule out this possibility, especially as the immediate models for these minarets, the 14th century minarets of Il-Khanid Iran, were brick structures (see later discussion). Like the adjacent mosque the complex has been discreetly restored over time. We have no information on the damage caused by the collapse of the first minaret after the lightning strike. However, the collapse of the mausoleum's dome and the remaining minaret in 1819 would explain two prominent areas of rebuilding within the tomb complex. The loss of a portion of the eastern wall, as shown on Burgess' ground plan of 1896 (Fig. 2), would be consistent wvtb. the collapse oi a tall structure such as the eastern minaret. The collapse of either the

caption that accompanies the plate reads: "In the centre is the Jumma Musjid and fallen Minar, mentioned in the memoirs"(Forbes, 1813, vol. IV, p. 364). Forbes' remark and sketch establish that the entrance to al-Kazaruni's mausoleum was originally topped by a pair of tower minarets. Although we do not know exactly when the first (western) minaret fell, this appears to have occurred reiat'we\y eariy, since the earty Y7tYi century account oi William Finch speaks of "a watch-tower of an exceeding

128

South Asian Studies 17

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

24. Raised muluk khanah in the western portion of the Kazaruni complex.

23. Carved doorframe connecting the main sanctuary of the Friday mosque and the western portion of the Kazaruni complex, seen from the side of the Kazaruni complex.

25. L-shaped walkway in the western part of the Kazaruni tomb complex, seen from the west looking towards the mausoleum.

dome or the minaret would also explain the 19th century restorations of the balcony within the entrance gateway (Fig. 15). A rosette carved on the underside of the pishtaq's balcony displays evidently 19th century features: for example, the design of its flowers can be paralleled with carving on the contemporary headstones of the Nawabs of Cambay, suggesting that this whole area was rebuilt and recarved at this time. The Kazaruni tomb complex is still one of the most impressive complexes of its genre in Gujarat, and must have been even more so before the lightning strike and earthquake destroyed this magnificent entrance. The funerary mosque and eastern courtyard The western end of the complex is occupied by a mosque consisting of four domed bays with an L-shaped walkway running along the east and south sides (Figs. 20 & 21). Like the mausoleum, this structure is a far more complex space than one would initially imagine from the published ground plans, being built on two storeys and provided with a walkway, and numerous staircases and

doorways that tie it to the adjoining Friday mosque and link it to the exterior. The easiest area to define and identify is under the north-western of the four domes, since a large white marble mihrab indicates that this was used for prayer, more specifically as a funerary chapel (Fig. 22). But this space also functions as a transition between the tomb complex and the prayer hall of the Friday mosque, since a doorway connects the two (Fig. 23). The space under the south-western dome appears to have been conceived as a miniature muluk khanah, since the upper half of this bay is divided by jali screens, in a fashion similar to the separation of the muluk khanahs in the main mosque, though it now lacks its floor (Fig. 24). Access to this muluk khanah is provided by a raised L-shaped walkway that runs along the southern and eastern sides of this part of the complex and connects to the staircases in the pishtaq and also to a separate small doorway in the south facade of the complex (Fig. 25). Traces of dowling along the edges of the walkway suggest that this was originally screened off by jalis. The provision of separate access to this area may confirm that it was intended to provide a secluded place for prayer.

129

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

To the east of al-Kazaruni's mausoleum is a large empty courtyard completely overgrown and filled with rubble, presumably from the collapse of the mausoleum's dome and the remaining minaret (Fig. 2). There is no evidence to suggest that this area ever housed any structures; whilst the east wall was rebuilt sometime after 1886, the intact south wall shows no traces of bonding with other structures. A number of minor graves here, and in the second small courtyard between the mausoleum and the funerary mosque, are evidence that these areas were used for later burials, possibly for family members, as was common throughout the Islamic world. The French traveller de Thevenot, who visited Cambay in 1665, mentioned that in the Friday mosque "there are many Sepulchres of Princes there also", a description that corresponds well to the eastern courtyard of the tomb complex and the burials there (de Thevenot, 1949, p. 18). The Kazaruni complex - phases of construction and patronage Unlike the Friday mosque the Kazaruni tomb complex lacks any foundation inscription indicating its patron and the date of it construction, and it is only the graves of al-Kazaruni and his wife at the heart of the mausoleum that lead to the assumption that this complex was purpose-built for him. It is not clear whether the complex was begun by al-Kazaruni during his own lifetime, as was often the case in the Islamic world, or whether it was constructed posthumously by members of his family, perhaps by his young wife Bibi Fatimah. It is even possible to envisage that the complex was begun by another patron and taken over for alKazaruni's burial, another practice frequent in the Islamic world. Unfortunately, existing sources provide little help in clarifying this matter but a few details can be established. The Friday mosque and tomb complex have often been mistaken for a single structure, and one may wonder whether they were in fact built as a single project and under a single patron, namely al-Butihari. The 725/1325 foundation inscription of the Friday mosque at Cambay does include a somewhat mysterious reference to the Friday mosque and its Hmarat - meaning building, structure or edifice - a detail that points at least superficially to this possibility. The term cimarat is regularly used in this sense in Indian Islamic epigraphy, from the early Sultanate period onwards. It is used either in association with a specific architectural term, such as mosque, well or fort, or alone, its meaning inferred from its location, as on a minaret, a gateway or a mosque. 25 However, outside Cambay there are no examples of the use of the phrase "the mosque and its building". In Ottoman Turkey the term Hmaret referred specifically to a

public kitchen providing food for the needy, but as far as I know the term is not recorded in this sense in 14th century India. In fact, it is highly unlikely that the cimarat mentioned in this inscription ever referred to a real structure at all! The foundation text of the 725/1325 mosque is heavily modelled on that of an earlier Friday mosque built at Cambay in 615/1218 (Desai, 1961, insc.I, pp. 4-7). The texts of the two Friday mosques share the same hadiih and Qur'anic verse {surah 72, verse 18) and an almost identical foundation text: "this [blessed]26 Friday mosque and its building were constructed wholly and completely, out of his own money from what Allah had given him through His grace and benevolence, merely for the sake of Allah the Exalted ...". Islamic inscriptions in Gujarat regularly copied the text, script and decorative motifs of earlier local examples. Indeed, the very same text, including the term Hmarat, was incorporated into a third mosque inscription at Cambay in 815/1412 demonstration enough of the practice of copying at the site (Desai, 1974, insc.III, pp. 5-7). Given this phenomenon it is highly questionable whether the Hmarat included in al-Butihari's inscription ever referred to a real structure, let alone to the tomb complex on its south. Indeed, the physical evidence suggests two separate building campaigns and therefore two distinct patrons. Even without a dated foundation inscription there is no doubt that the tomb complex was constructed after the Friday mosque had been substantially completed, and therefore probably by a different patron. A clear break in the masonry bond between the two buildings on the exterior of the west and east walls, at the point where the Friday mosque meets the tomb complex, indicates that we are dealing with two separate phases of construction, not a single building project (Fig. 26). The whole south wall of the mosque (or the north wall of the tomb complex) provides evidence for the fact that the complex was built against the mosque, and not the reverse. The mausoleum was built on a different module from the adjacent Friday mosque, with the result that its pillars intercalate rather clumsily with the windows and doorways of the mosque wall (Fig. 2). However, the three exterior mouldings that encircle the two structures are continuous (Fig. 26), and the bays of the funerary mosque follow the same module as the Friday mosque and have similar architectural decoration (the mihrab in the tomb complex is almost identical to those in the Friday mosque). This suggests that, whilst the Friday mosque and tomb complex were not planned and built as a single project, they were constructed in close sequence. Until a more plausible candidate comes to light, it is reasonable to assume that the complex was built to commemorate al-Kazaruni, and most probably, after his death. Whilst it is difficult to estimate

130

South Asian Studies 27

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

construction times in medieval India, we do know, for example that the first phase of the Quwwat al-Islam mosque in Delhi took six years to complete, being founded in 587/1191-92 and finished in 592/1197 (Page, 1926, insc.I, p. 29 and insc.lll, p. 29). If the Friday mosque at Cambay was founded in 725/1325 one can imagine it approaching completion in the early 1330s. Given the break in the bond between the two structures, this might suggest that the tomb complex was begun shortly after al-Kazaruni's death in 734/1333 and perhaps finished towards the end of the 1330s.

c

Umar ibn Ahmad al-Kazaruni

The size and sophistication of the complex certainly befit a character such as al-Kazaruni and the milieu in which he moved. What scant data there is establishes that c Umar al-Kazaruni was one of the elite merchants of India. The nisbah al-Kazaruni is of Iranian origin and denotes family roots in, or connections with, the town of Kazarun near Shiraz in southern Iran, and it is clear that he was one of the many foreign merchants who lived and traded at Cambay. Like many of the greatest merchants of the period, al-Kazaruni was also closely involved with the Tughluq court and the politics of the day. Ibn Battuta refers to al-Kazaruni as Malik al-Tujjar or King of Merchants, whilst another inscription from Cambay dated 726/1326 gives him the title Malik Muluk al-Tujjar, an intensive form of the title which translates literally as King of the Kings of Merchants (ARIE, 1956-57, insc. D 52).27 Although the precise history of this title is still obscure, it was an officiaJJy conferred post under the Tughluq Sultans, since we know that a certain Malik Shihab al-Din Abu Raja was appointed to this post and awarded the ciqta of Navsari on the accession of Muhammad ibn Tughluq in 725/1325 (Habib & Nizaxni, 1992, p. 486).2S The title suggests that incumbents were responsible for overseeing merchants and trade within the Sultanate. The 726/1326 inscription from Cambay suggests that, unless the intensive form of the title was used more as an eulogy than as an official title, alKazaruni succeeded Abu Raja in the post sometime in 1326, but the 'iqta he was awarded is not known. As Ibn Battuta noticed, the foreign merchants of Cambay were avid patrons of architecture, and alKazaruni appears to have been no exception. "The house of Malik al-Tujjar al-Kazaruni with his private mosque adjacent to it" were among some of the grand buildings of Cambay singled out by the Moroccan traveler (Ibn Battuta, 1976, pp. 172-173).29 Another of al-Kazaruni's architectural projects, this time directly related to trade and the protection of shipping, involved the fortification and repopulation of the island of Perim, some four miles off the trans-shipment port of Gogha on the western side of the Gulf of Cambay (Ibn Battuta, 1976, p. 176).30 The

scale and magnificence of his funerary complex whether started during his lifetime, or after his death by his entourage -testifies similarly to the level of patronage he was able to command. According to Ibn Battuta, al-Kazaruni died unexpectedly in an ambush by Hindu bandits as he was taking the considerable tax revenue from his iqtac in Gujarat to Delhi (Ibn Battuta, 1976, pp. 67-68). Although local unrest and banditry were common in Gujarat at this time, Ibn Battuta reports the rumour that the attack was a carefully organised plot by the incumbent vizier, Khwajah Jahan, who feared that al-Kazaruni had been appointed to replace him.31 Although this rumour is impossible to verify, the fact that it was still talked about a decade after al-Kazaruni's death indicates his importance in the politics of the period. Al-Kazaruni's murder at the hands of Hindu bandits also appears to have won him the highest status of Islamic martyrdom, that of battlefield martyr or shahid al-ma'rakah. The evidence for this comes from his headstone which carries a long Qur'anic extract (surah 3, verses 169-71) about the first Muslim martyrs of the battle of Uhud. The verses are inscribed just above the text of al-Kazaruni's epitaph, and the physical proximity of the two seems intended to

26. Detail of the break in the masonry bond between the Friday mosque and Kazaruni complex on the western qibla wall.

131

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

^JUMin'-"^y 1{ >!"<-

""'

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

structure with provision for the main burial, subsidiary burials, prayer, the call to prayer, keeping watch over the Gulf of Cambay, and no doubt housed many additional activities. By the 14th century tomb complexes were a common form in Islamic architecture, from north Africa and Spain to India in the east. Among its contemporaries one might single out the funerary complexes of the Mamluk Sultans and their nobles in Egypt and Syria, and those of Il-Khanid Iran, where the Il-Khanid Sultans and their viziers built a number of extremely large complexes during the first half of the 14th century. Sultanate India also had a discreet and very distinct tradition of such complexes. 33 Given the cosmopolitan character of Cambay and al-Kazaruni's milieu, it is more than likely that many of these complexes were familiar at first hand or through the accounts of other merchants and travellers. However, the Kazaruni complex does not appear to follow any one specific geographical tradition. Most important is the question of the pairing of the Friday mosque and tomb complex. The structures work so well as a whole that it is easy to overlook how unusual this association is. No other Friday mosque in western or northern India has a mausoleum, let alone a whole tomb complex, so well integrated into its structure, and there are no Friday mosques elsewhere in the Islamic world where this is found. In India important mausolea are often associated with great Friday mosques, but are always physically separate from them. The mausoleum of Iltutmish at the Quwwat al-Islam mosque in Delhi is built behind the qiblah wall, c Ala' al-Din Khalji's funerary madrasah is built behind the qiblah wall of the same mosque. No other Tughluq Friday mosque in Gujarat had a mausoleum physically attached to it. At Ahmedabad the mausoleum of Ahmad Shah I and that of the female members of his family, the so-called Rani ka Hazira, are both closely related to his great 827/1424 Friday mosque, but are again physically separate. Only at Pandua in Bengal is the so-called Sulayman's tomb chamber built against the qiblah wall of the 776/1374-75 Adina mosque. The relationship between mosque and tomb at Cambay is all the more unusual in that the tomb complex was allowed to dominate the mosque in many aspects. Today the Friday mosque dominates the tomb complex in terms of both area and height (Fig. 3), and most travellers arrive by land and enter the complex via the north gateway of the Friday mosque (Fig. 5). However, in the past the scale of Kazaruni's dome and the minarets reversed this balance. As Forbes' sketch shows, it was the dome and minarets of the mausoleum, rather than any element of the mosque, that dominated the Cambay skyline, literally overshadowing the adjacent mosque (Fig. 19). They also challenged the main axes of the Friday mosque, robbing the north gateway of its

27. View of al-Kazaruni's cenotaph from the courtyard of the Friday mosque.

liken him to these first martyrs. The iconography of martyrdom is continued in the actual form of his headstone, which is topped by a miniature pillar, a form used throughout Gujarat to denote a martyr's grave. 32 The text of his epitaph refers to him grandly by the posthumous titles Malik Muluk al-Sharq wa al-Wuzara' mashhitr al-Arab wa al-cAjam, literally King of the Kings of the East and of Ministers, Celebrated in Arabia and Other Islamic Countries. Tomb complexes and the pairing of Friday mosque and mausoleum Al-Kazaruni's grave complex obviously follows in a well-established Islamic tradition of multi-functional funerary complexes. These could incorporate, besides the mausoleum, a mosque or funerary chapel and diverse other structures such as a madrasah, a khanqah, a library or even a hospital or an observatory. Unfortunately, without the foundation inscription of the Kazaruni complex we have lost the precise term or terms by which it was originally known, and with that any firm indication of what activities were provided for. In spite of this it is abundantly clear that it was a multi-functional

132

South Asian Studies 17

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS...''

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

importance and establishing the southern entrance - via the tomb complex - as the principal point of entry. Even today, as one enters the mosque through the north gateway it is impossible not to be drawn across the courtyard towards the funerary complex on the south side, since al-Kazaruni's cenotaph is sited directly opposite the north entrance, glimpsed though the southern doorway (Fig. 27). The closest parallel for the physical relationship and balance of the Friday mosque and Kazaruni complex, though by no means a direct source, appears to be in 13th century Anatolia. Here Friday mosques were sometimes associated with charitable institutions, the various parts being physically contiguous and often equally balanced. For example, the Friday mosque at Divrigi (626/1228-29) has a hospital attached to its qiblah wall; whilst the Khwand Khatun complex at Kayseri (635/1237-38) comprised a Friday mosque, a madrasah, a bath and a mausoleum. 34 At such a distance in time it is difficult to explain the prominence of al-Kazaruni's tomb complex and its unique integration with the Friday mosque. Perhaps only his status as a battlefield martyr is sufficient to explain this. The association of the two structures created a major religious centre - a Friday mosque and a martyr's shrine - at the very heart of the port. At the very southern edge of the city, facing onto the port area, these were the first major structures encountered by any person arriving at Cambay, a 14th century precursor of Bombay's Gateway of India, the southern gateway announced the might of Tughluq India. Though we know nothing of the original 14th century environment within which these buildings were placed, later descriptions indicate that they were at the heart of a larger landscaped and built seafront developed by the Sultans of Gujarat.33 The early 17th century descriptions of the mosque and tomb complex by della Valle make clear that both structures were still busily frequented and were close to at least one other imposing mausoleum, 36 as well as a large talav or tank (described as "a great Piscina or Lake"). Contiguous with this was a small garden "sometimes belonging to the kings of Guzarat", adorned with "running water which at the entrance falls from a great Kiosck, or cover'd place to keep it cool" (della Valle, 1892, pp. 68-69). PART II KHALJI ARCHITECTURE IN DELHI AND THE SOURCES OF THE CAMBAY FRIDAY MOSQUE Cambay's Friday mosque has received little attention since it was first published over a century ago by Burgess. The general paucity of research into Indian Islamic architecture may be partly to blame, but it is also

true that the mosque lulls the visitor into a false sense of familiarity. To the visitor fresh from the Quwwat al-Islam mosque in Delhi, or the Arha'i din ka Jhompra mosque at Ajmer, the mosque provides an immediately recognisable environment, a hypostyle plan mosque built in spoliated stone with an arched fa?ade screen across its trabeate prayer hall (Fig. 3). One would only need to add a programme of Islamic inscriptions and a minaret a second Qutb Minar, or perhaps a pair of pseudominarets as at Ajmer - and the resemblance would be complete. It is easy to forget the hundred years and thousand kilometres that separate these structures. The Friday mosque at Cambay certainly bears little resemblance to contemporary Tughluq Friday mosques in Delhi. Though the Friday mosque at Tughluqabad is only a ruin it is clear that it had a hypostyle plan mosque, apparently without a screen fagade, and was built from ashlar faced rubble, with the typical Tughluq battered walls, influenced by the brick architecture of Multan. But how and why does it follow these early Sultanate models? Post-conquest mosques and parallels with the Quwwat al-Islam mosque Anthony Welch and Howard Crane have already suggested that provincial Muslim styles under the Tughluqs were set more by "the ghazi ideal and the availability of local materials" than "the capital mode" (Welch and Crane, 1983, p. 125), presumably an allusion to the practice of building early mosques from temple spolia. Certain aspects of the Cambay Friday mosque might indeed class it with this type. The type of mosque to which Welch and Crane appear to refer is not specifically Tughluq, but goes back to the very first mosques built in India after the Ghurid conquest. As the foundation inscriptions on the Delhi and Ajmer mosques testify, in their first phases these buildings were simple hypostyle structures with open trabeate prayer halls. The Delhi mosque was founded in 587/1191-92 and finished in 592/1197, but the faade screen was only completed in 594/1199 (Page, 1926 insc.IV, pp. 29-30), almost two years after the main body of the mosque - enough of a delay to suggest that the screen was an afterthought. At Ajmer the main mosque was completed in 595/1199, but here it was another thirty years before the prayer hall was given a fagade screen by Sultan Iltutmish in around 627/1229-30 (Horovitz, 1911-12, insc.XXXII, p. 30). India is peppered with mosques of this type, marking the ebb and flow of Muslim control over the centuries. The simplest examples often have only an open trabeate prayer hall, without even side arcades or a central courtyard, and are assembled from temple spolia. Many have not been published, while others no longer surviving can be

133

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

traced through remarks in epigraphic publications and archaeological reports. Several hypostyle mosques of the early 13th century have survived in Rajasthan: the Shahi Masjid at Khatu, probably dated 599/1203 (Shokoohy, 1993, pp. 107-10), the Chaurasi Khamba mosque at Kaman and the Ukha Mandir mosque at Bayana (both c. 1206 and 1210 AD) (Shokoohy, 1987). The Qazi mosque at Bayana (705/1305), the Dini mosque at Rohtak (708/1309) and the Ambiya Wali mosque at Fatehpur Sikri (713/1314) all had simple trabeate prayer halls, built largely from temple spolia, with a walled courtyard and sometimes an entrance gate (Yazdani, 1917-18, pp. 19, 21 and 31 respectively). The Friday mosque at Dawlatabad in the Deccan was constructed under Khalji patronage in 1318 AD along this basic model, as was the mosque of Karim al-Din (c. 1320 AD) at Bijapur (Burton-Page, 1986, p. 62 and Fig. 8). In 725/1325 the hypostyle Friday mosque at Khanapur in Maharashtra was built from Hindu spolia (Welch & Crane, 1983, p. 26). In Gujarat, the first and largest mosque of this type was the Adina mosque built in 705/1305-06 at Anhilawad Patan by the Alp Khan, the leader of the conquest and first governor of the region. Though the mosque was destroyed in the late 18th century, descriptions suggest that it was enormous, measuring some 100 by 121 m. (330 by 400 ft.) and followed a traditional hypostyle plan (Burgess & Cousens, 1903, pp. 53-54). There is no evidence that it had an arched facade screen. The mosque was constructed entirely in white marble taken from local temples, and sources such as the Mir'at-i Ahmadi extol its sheer scale and the number of columns employed. Nevertheless, the Friday mosque at Cambay does not fit comfortably within this type. Though it employs spoliated material, it does so in an altogether discreet manner - there are none of the hacked off images visible in Delhi - and alongside a large amount of purpose carved material. There is none of the haste sensed in some of these very early mosques, and it is the only one to have a solid screen across its trabeate prayer hall, a feature that points unequivocally to the Quwwat alIslam mosque in Delhi and its "twin" at Ajmer. Though the first facade screen at Delhi was a later addition, the idea was faiuvfully continued in every subsequent enlargement of the Quwwat al-Islam complex during the 13th and 14th centuries, thus ensuring the currency of this feature at the capital for over a century. Iltutmish's extension of the Delhi mosque, undertaken around 627/1229-30, included a magnificent arched screen as an integral part of the mosque plan (Page, 1926, insc.V, p. 30) and it was again Iltutmish who added the screen facade to the Ajmer mosque around the same time. The Delhi and Ajmer facade screens are unique to India; no parallels are known in the earlier Islamic architecture of Iran or

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

Central Asia, nor indeed elsewhere in the Islamic world. The innovation appears to have been born in response to the particular architectural conditions of early Muslim India, the main effect of these screens being to impart an immediately "Islamic" feel to the architecture, concealing the trabeate construction of the prayer hall and evoking the large iwan facades of the Iranian world (see later discussion of Seljuq iwan and dome combinations). But if the screen facade began life as a cosmetic mask, by the middle of the 13th century it had visibly become part of a new mosque plan. In this context, the presence of a facade screen at Cambay is extremely significant because, beyond the Delhi and Ajmer mosques, no other 13th century or early 14th century mosque in India had a screen of this type. In other words, the idea of a screen facade was exclusive to the Delhi and Ajmer mosques until it appeared for the first time at Cambay. Significantly, the Cambay screen closely follows these two northern models in the details of its composition. At Cambay, as at Delhi and Ajmer, the central arch of the screen is accentuated in width and height (Fig. 4). In the first rendering of this idea at Delhi and Ajmer, no effort appears to have been made to integrate the screen with the prayer hall behind. As a consequence, the modest single storey prayer hall "peeks" through the main central arch of the screen in a rather disjointed and incongruous fashion. By contrast, in the later extension of the Quwwat al-Islam mosque under Iltutmish, these two elements were married by the introduction of a screened back, or clerestory, to the rear of the central arch (Page, 1926, Plate IV). At Cambay too, exactly this feature is employed around the three arches of the screen (Figs. 4).

c

Ala' al-Din Khalji's extension of the Friday mosque in Delhi

The appearance of the facade screen at Cambay can only be understood in the context of the single most important architectural project of the early 14th century: c Ala' al-Din Khalji's scheme for the enlargement and expansion of the Quwwat al-Islam mosque; Delhi, around 710/1310. Whilst almost nothing of this phenomenal project remains above ground, archaeological excavations and contemporary references reveal its scale and ambition. The expansion included the doubling of the area of the mosque, the construction of a number of monumental gateways - of which the LAla'i Darwazah is the single remaining example - and the construction of a second Qutb Minar, double the size of the first. The project appears to have reached an advanced stage of completion, since Ibn Battuta described the mosque with its four courtyards and white walls during his stay in Delhi in the 1340s (Ibn Battuta, 1976, pp. 26-27).

134

South Asian Studies 17

"A COLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

The Quwwat al-Islam complex was already a symbolically charged complex - with its inscriptions proclaiming the might of Islam, the Qutb Minar belongs to a long tradition of Ghurid victory towers - and there is no doubt that the expansion of the complex added further layers of symbolism. Friday mosques hold a unique place in the religious and political life of each community since the entire male Muslim population of a locality is required to gather together for the Friday midday prayers. These prayers are first and foremost a religious act, but they also comprise a political dimension, being preceded by the reading of the khutbah in the name of the ruling Sultan. Friday mosques are therefore the ideal theatre for the communication of political messages to the widest audience possible. The fact that l Ala' al-Din Khalji chose to expand the existing Friday mosque of Delhi, rather than found a new structure, can be seen as a demonstration of his adherence to the idea of the Sultanate and its continuation. Moreover, by doubling the size of the early structures and literally swallowing them up within his new mosque, his project expressed the extent to which the Khalji conquests had surpassed those of the early Sultanate. Ala' al-Din's project was known across the Muslim world and appears to have had a profound influence upon subsequent Khalji and early Tughluq architecture, especially in the provinces. The mosque became one of the major "sights" of India: as one would expect it is mentioned in Amir Khusraw's Kliaza'in alFutuh (Amir Khusraw, 1931, pp. 14-17) and Ibn Battuta devotes a long description to the new expanded Friday mosque with its multiple courts and massive minaret (Ibn Battuta, 1976, pp. 26-28). Purely in terms of manpower,' Ala' al-Din's patronage must have created a massive influx of labour to Delhi and Amir Khusraw's account of the project is focused around the massive search for stone to complete the work. When the project finished these craftsmen and architects left to work on other projects in other regions, taking these "new" forms with them. But the best measure of the attention that the project attracted is provided by two Mamluk geographies of the 1320s and 1340s. The mosque is mentioned in the Tatfwim al-Buldan or "Table of the Countries", a famous geographical treatise by Abu alFida' the Ayyubid Prince and Governor of Hamah in Syria, completed in 721/1321. "In its [Delhi's] mosque there is a minaret the like of which is not found in the world; it is built of red stones and has about three hundred stairs. It has extensive dimensions, is very high and has spacious lower parts" (al-Qalqashandi, 1939, pp. 27-28). The minaret's height is also mentioned in the Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar of Shihab al-Din Ahmad al-cUmari (d.749/1349,) where it is given as about six hundred forearms (al-Qalqashandi, 1939, p. 28).37 The crucial impact of c Ala' al-Din Khalji's project is

c

demonstrated by the fact that a range of architectural forms previously unique to the Quwwat al-Islam mosque and its "twin" in Ajmer suddenly reappeared throughout India in the late 1310s and 1320s, exactly the period when these forms were revived by the enlargement of the Delhi mosque. The falanges found on the Qutb minar in Delhi and on the buttresses and twin minarets of the Arha'i din ka Jhonpra mosque at Ajmer, were unique to these two structures until they were revived for the exterior of c Ala' al-Din Khalji's second Qutb Minar. Thus no falanging is found on 13th century Rajasthani mosques such as the Shahi Masjid at Khatu a mosque which otherwise follows the example of Ajmer in many details 38 - or the Chaurasi Khamba mosque at Kaman and the Ukha Mandir mosque at Bayana. Yet falanges reappear suddenly in the second decade of the 14th century, in the decoration of the 'idgah at Jalor in Rajasthan, dated by inscription to 718/1318-19, at the Friday mosque at Dawlatabad in the Deccan, constructed under Khalji patronage in 1318 AD (Koch, 1991, pp. 100 and 103) and in the pair of stellate plan "turrets" or pseudo-minarets above the central gateway of the Ukha Masjid in Bayana, dated by inscription to 720/1320-21 (Shokoohy, 1987, p. 126). Falanged corner buttresses are also found on the so-called Kothi gateway at Cambay, a structure that probably also dates to the 1320s (Fig. 28). Many later structures across India were to continue this motif (see Koch, 1991).

28. View of the Kothi gateway at Cambay, first half of the 14th century AD. view from the south-east showing the falanged corner buttress.

135

ELIZABETH LAMBOURN

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

Whilst the spread of falanges throughout Indian architecture was first noted by Ebba Koch (Koch, 1991), it was not explicitly linked to c Ala' al-Din's great project. The example of the Friday mosque at Cambay suggests that the arched fa9ade screen was but another characteristic element revived by c Ala' al-Din's project and then spread throughout India. As we have seen, in the 13th century only the Delhi and Ajmer mosques appear to have had facade screens, yet these reappear suddenly in Indian architecture after 1310. The first germ of this idea outside Delhi was perhaps in the so-called mosque of Shaykh Barha at Zafarabad near Jaunpur in eastern India, which carried a foundation inscription dating it to 711/1311 and the reign of c Ala' al-Din Khalji (Fuhrer, 1889, p. 3). Here the centre of the faade of the prayer hall was marked by "a large arch between two piers" which apparently gave a lofty fagade (op. cit., p. 30). In Gujarat the idea appears first in the Friday mosque at Cambay (725/1325) and subsequently in the mosque of Hilal Maliki at nearby Dholka (733/1333) ?9 Other elements of the Delhi project, less directly indebted to early Sultanate models, also appear to have been diffused into the provinces to influence the Friday mosque at Cambay. The c Ala'i Darwaza cleverly exploits the contrast of white marble and red sandstone for its exterior facing. Polychrome stonework obviously found favour in Tughluq structures at the capital and appears for the first time in the tomb of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq c. 1325. Ibn Battuta also mentions a partly built mosque at Delhi, allegedly constructed by Muhammad bin Tughluq which "was of white, black, red and green stones" (Ibn Battuta, 1976, pp. 27-28). However, an earlier provincial example suggests that this idea may have already begun to spread in the provinces during the Khalji period, in response to work on the Quwwat alIslam mosque. The red sandstone gateway of the 720/1320-21 Ukha Masjid at Bayana has contrasting bands of white marble and the central arch is defined by a very deliberate use of alternating red and white blocks, which evoked for Sir John Marshall "much of the ornamentation of the Qutb buildings" {Yazdani, 1917-18, p. 41).40 The polychrome stonework found throughout the Friday mosque at Cambay (Figs. 5,6,9 & 11) may also be inspired more by Khalji models than by early Tughluq architecture at the capital. The vocabulary of conquest Given the weight of meaning already attached to the Quwwat al-Islam complex, there seems little reason to doubt that some of the symbolism of the complex was perpetuated in these "quotes". This is not a new idea; a decade ago Ebba Koch argued that the repeated uses of falanges on minarets, towers, buttresses and even domes throughout Indian Islamic architecture were deliberate

quotes back to the form of the Qutb Minar. These quotes, she proposed, were made by rulers wishing to "transfer the significance of the prototype, which had become the landmark of the establishment of Muslim rule in India, onto their own constructions" (Koch, 1991, p. 101). Koch explained the fact that these falanges are often included as only minor decorative motifs on a variety of structures (often not minarets) as a reflection of the medieval principle of evoking the meaning of a prototype through selected elements rather than faithfully reproducing the entire original. The evidence reviewed above suggests that Ebba Koch's original idea can be extended to include other elements of the Quwwat al-Islam complex. Perhaps it was the entire Quwwat al-Islam complex, not simply the Qutb Minar, that became "the landmark of the establishment of Muslim rule in India", and more than one element could "carry" with it the significance of the whole. Nevertheless, the task of disentangling what precisely these "quotes" were intended to mean is far from easy. Many of the buildings that "quote" the Quwwat al-Islam complex have no inscriptions to clarify their symbolism and intent. Furthermore, the complex itself had already become imbued with multiple layers of symbolism, that of the original mosque and the first conquest of India, of Iltutmish's extension, of the Qutb Minar and then of c Ala' al-Din Khalji's own project. Like Ebba Koch, we can safely venture that at its most generic, the allusions to the plan of the Quwwat al-Islam mosque in the Friday mosque at Cambay proclaim the establishment of Muslim rule in Gujarat, and more specifically Cambay. But the message is perhaps rather more specific, and we should take into account the twenty-year "delay" between the actual conquest of the region and the construction of the mosque, and the consequent political and material changes. As the Friday mosque at Cambay was not built in the immediate aftermath of the conquest of Gujarat in 704/1304-05, it demands interpretation in another context. The reasons for the delay are simple: western India's long history of Muslim settlement, going back to the late 10th century meant that many towns already had mosques and Friday mosques. The site of Cambay was developed around 971 AD, and appropriately enough, the earliest specific reference to a Friday mosque at Cambay is in Ibn Hawqal's Ashkal al-Bilad, finished in 366/976, where he mentions that "there are Friday mosques at Famhal, Sindan, Saimur and Kambaya" (Ibn Hawqal, 1867-77, p. 38). At most it may have been necessary to enlarge these existing mosques to provide for a larger Muslim population. The Adina mosque at Patan seems to be the only exception to this, where, at the Solanki capital, it was clearly imperative to construct a large Friday mosque immediately after the conquest. As far as can be gauged from the surviving buildings it was

136

South Asian Studies 17

"ACOLLECTION OF MERITS..."

Downloaded by [Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology Library] at 04:08 21 July 2013

only from the 1320s onwards that the construction of monumental Friday mosques began on a large scale, at Bharuch in 721/1321, at Cambay in 725/1325 41 , at Dholka in 733/1333, at Kapadwanj in 772/1370-71, and at Mandal. The timing of these constructions relates to the history of Tughluq rule in Gujarat, for though a region could be conquered, this did not mean that the entire region had come under secure Muslim government. Although Gujarat was conquered in 704/1304-05, the first twenty years of Muslim rule there were extremely loose. For much of this time it was, in practice, beyond the control of Delhi, either quietly independent or sometimes in open secession from the capital, an instability that cannot have encouraged large architectural projects. The period around 725/1325-26 marks a critical turning point in the Muslim control of Gujarat. In 725 Muhammad ibn Tughluq came to power and established strong central control over Gujarat by radically altering the structure of Muslim government. Whereas Gujarat was previously governed from the regional capital of Anhilawad Patan by a single governor or na'ib, Muhammad ibn Tughluq followed the principle of divide and rule, introducing a four-part power structure with its own natural checks and balances. 42 Although the Friday mosque at Cambay was not built under the patronage of the Tughluq Sultan himself, its patron al-Butihari was at the heart of this process of consolidation through his military career in Punjab, Bengal and later Telangana. In the political context of the 1320s, the allusions to the architecture of the early Delhi Sultanate communicated not only the Muslim conquest of Gujarat in 704/1304-05 but also and perhaps above all the renewal of Tughluq central control over the region, and of course specifically Cambay. 43