Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gross Rita Religious Diversity

Hochgeladen von

Carlos PerezOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gross Rita Religious Diversity

Hochgeladen von

Carlos PerezCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY: SOME IMPLICATIONS FOR MONOTHEISM by Rita M.

Gross

Coming to terms with genuine pluralism is the most important agenda facing religious leaders. RITA M. GROSS is author of Buddhism after Patriarchy, Feminism and Religion: An Introduction, and most recently Soaring and Settling: Buddhist Perspectives on Contemporary Social and Religious Issues. This essay first appeared in Wisconsin Dialogue: A Faculty Journal for the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire 11 (1991): 3548, and is reprinted by permission. It is dedicated to the memory of Howard Lutz, Professor Emeritus of History, whose loving companionship during the time in which this article was written is greatly appreciated. Clearly, the diversity of religions in the world has been a fact throughout the entire history of all the world's major living religious traditions. Nevertheless, this diversity has been made the basis for contention rather than community in many cases, and the monotheistic religions have often been among the worst offenders on this score. The strong tendency to display hostility toward different religious positions is connected with a strong tendency toward xenophobia and ethnocentrism. This reaction seems to be built into conventional human responses and has even been included among the major responses of religious people to their environment by the great historian of religions, Mircea Eliade. He hypothesizes that homo religiosus strives to live at the center of his mythological universe, which is felt to be a cosmos,organized space inhabited by human beings. Beyond that space is chaos, whose inhabitants are felt to be demonic or subhuman.(1) Because the tendency to be hostile to people who are different is so strong, it is an important religious problem. This essay will systematically consider the dynamics of religious pluralism and propose techniques for dealing with diversity. Religious diversity is an important component of cultural diversity, which educators are now taking seriously in their pedagogies. However, cultural diversity and religious diversity are often evaluated quite differently. In our society now, there is at least a polite and superficial consensus that cultural diversity is here to stay and may enrich life. Minimally, people realize that cultural, ethnic, and class chauvinism create problems and are inappropriate,

though they may be difficult to overcome. Regarding religious diversity, quite a different evaluation is often employed. Many people value the feeling that their religion is indeed superior to others and regard such religious chauvinism as a necessary component of religious commitment, or even a virtue to be cultivated among the faithful. In their official theologies, most religions have dealt with religious diversity only in a cursory or inadequate fashion. Frequently, religions have encouraged mutual hostility by teaching that foreign religions are not only different, but also demonic, or at least inferior. The ethical problems with such a position should be obvious. The position is clearly inadequate in any age and place; in the global village of the late twentieth century it is also dangerous. Nevertheless, it continues to be popular in many religions and is at least partially responsible for many of the numerous conflicts currently disrupting our world. In this essay, I will explore more ethically sensitive and intellectually satisfying ways of combining commitment to a specific religion with the reality of religious diversity than the conventional ones outlined above. I will direct my comments mainly at monotheistic religions for two obvious reasons. Most readers of this essay will come from monotheistic backgrounds. And monotheistic religions have had the most difficult problems in resolving the issue of religious diversity. All religions produce a kind of elementary religious chauvinism because of universal human weaknesses. However, only the monotheisms raise this homegrown psychological hostility to diversity into a theological principle. It is very tempting for one who believes that one universal deity created and controls the entire cosmos to assume that this deity wants only one religion to be practiced by all humans. That religion, of course, is "ours," which leads to the rather absurd situation of monotheists condemning each other to oblivion for following the wrong kind of monotheism. Many monotheists also assume, mistakenly, that nonmonotheistic religions are equally exclusive in their claims and that all religions feel certain about their position as the "one true faith." The creators of monotheistic symbol systems could, with equal logic, assume that the universal deity gave humans many religious paths, as s/he gave them many cultures, skin colors, and languages, but this has not been the dominant monotheistic position historically. This position is now becoming more prevalent among segments of leadership of monotheistic religions, however, and it has long been the position of nominally polytheistic, but essentially monistic, Hinduism. My method for this essay is that of a trained historian of religions, deeply interested in both normative and descriptive dimensions of religious diversity. Because I am summarizing immense amounts of information and comparing the world's major religions with one another to propose

some philosophical positions on religious diversity, I presume elementary knowledge of world religions. My generalizations can be understood without such knowledge but cannot fruitfully be debated if one is familiar with only one religion. Students of religion have long recognized that the world's religions can be divided into two groups in terms of their attitudes toward other religions.(2) Some religions, often called "universalizing" religions, have a religious message and set of practices that could be universally relevant, true for all people regardless of culture, for all time. These religions sometimes develop strong missionary movements which attempt both to undermine other religions ideologically and to convert members of other cultures to the supposedly universally relevant and true set of religious beliefs. Often such conversion attempts are motivated by the conviction that those who lack the proper religious perspective are in serious danger of long-term malaise. Additionally, such religions are often relatively uninterested in culture-bound practices and habits having to do with diet, social customs, family law, purity and pollution, or the minutia of daily life, et cetera. The individual's mind state and belief system are usually considered to be far more important than conformity to behavioral norms. This kind of religion is also far more familiar to most people in Western cultures than is its counterpart. Nevertheless, for most of human history most religions have not presumed to possess universal significance. This position is not taken out of ignorance of the existence of other religions, but out of a judgment that a specific religion has, at most, a claim on those who belong to the culture in which that religion is found. To be born into a culture is to inherit a religion; to be born into a different culture is to inherit a different religion. To change religions is to change cultures, to change lifestyle and identity, to be adopted by the culture whose religion one adopts. However, such adoption is not encouraged or expected, since no one presumes that members of other cultures are inherently deficient; they are merely different, and unless hostility develops over an economic matter or an issue of prestige, there is little reason to disparage a different culture and its religion. Furthermore, though there is a clearly developed system of belief, myth, and ritual in this kind of nonuniversalizing religion, membership is more often measured by conformity to cultural mores and by participation in important group activities than by orthodoxy of belief. Because they present obvious and intimate connections between religion and culture, such religions are often called "ethnoreligions." Classical monotheism in its stereotypical form clearly assumes a universalizing stance. However, monotheism did not emerge into history full-blown in this form. A brief sketch of the emergence and

development of monotheism can help locate monotheism's particular difficulties with religious pluralism. It seems safe to say that the earliest "monotheism" having long-term historical consequences, early Judaism, probably better labeled as "ancient Israelite religion," actually had most of the characteristics of an ethnoreligion. In early Israelite history, only Israelites were expected, indeed privileged, to observe Israelite beliefs and practices. Certainly there was no major effort to spread these practices and beliefs to nonIsraelite people; it was sufficiently difficult to cajole the Israelites into retaining them. However, in this phase of Israelite history, certain attitudes regarding foreign religions were prevalent. These attitudes, which are not especially characteristic of ethnoreligions, were critical for the long-term. Monotheism, for early Israelite religion, probably meant that Israelites should worship only the Israelite deity, rather than a claim that this deity alone existed. However, the attempt to convince Israelites to worship their deity alone prompted virulent attacks on the deities of the surrounding nations, especially the Canaanites, forging that classic and invidious category that has so colored monotheism's reactions to other religions throughout history -- "idolatry." A major change in attitude important to the transition from ancient Israelite religion to early Judaism is a tendency towards a universalizing perspective, away from the ethnic stance. Israelites, militarily defeated by a stronger force and taken into captivity in 586 B.C.E., did not follow the typical ethnic response of assimilating religiously and assuming that their god had been defeated by a stronger deity. Rather, they retained their allegiance to their own conceptualization and naming of deity, even in exile, reasoning that the Israelite deity controlled "the nations" as universal, sole deity and had ordered their defeat and exile. This experience fostered the transition from ancient Israelite religion to early Judaism and was probably the single most important event in the development of classical monotheism as a universalizing religion. One important ingredient in this transformation involved postulating a wider relevance for Israelite-Jewish religious beliefs and practices. The one deity was thought to be no longer merely the one deity properly worshipped by Israelites; it was also claimed to be universally the one deity, the deity who had allowed victory over Israelites and who meted out the destinies of all people, not merely the Israelites. In that case, restricting the worship of this deity to Israelites was of questionable morality. Therefore, though not without opposition, Judaism became a universalizing religion, willing to allow non- Israelites to observe Jewish practices and to hold to Jewish beliefs. In the late pre-common and early post-common era centuries, Jews aggressively sought converts and were quite successful in their efforts. Attracted to the monotheistic creed and relevant ethic of Judaism, people put up with Jewish ethnic requirements

for circumcision, kashrut, et cetera. This period ended when Judaism's conversion practices were outlawed by its newly dominant offshoot -- Christianity. Christianity saw itself as the new covenant between the monotheistic god and the created world; it saw no reason, especially after it gained political hegemony, to allow another (and older) version of monotheism to compete to gain converts to monotheism. Christianity's appeal was strengthened when it dropped most of the ethnic practices required by Jewish monotheism. Consequently, in most parts of the Greco-Roman world, and later the European world, Judaism survived as an enclave, a tribal remnant in the larger world, at least as defined by history's winners, Christians, in this case. Christianity battled the "pagan" religions of the Greco-Roman and Northern European peoples as ancient Israelites had battled "idolatry," thus adding another important term to the rhetoric of monotheism's denigration of other religions By the time Islam emerged into history, the attitude that there is a universal deity to be worshipped and obeyed by all people of all cultures was unquestioned and unquestionable. Muslims claimed only that Christian messages from that one universal deity had been superseded and made obsolete by the revelations given to Mohammed. Thus the only real question was who spoke for the universal deity, who, in fact, was the seal of the prophets. That question has been the fundamental dividing issue among the three monotheistic faiths, as each asserts the genuineness and supremacy of its own scripture and claims that the others' scriptures are not relevant messages from the one universal deity. Thus was formed monotheism's specific variant of the universalizing stance, a style of universalizing that has special difficulties, both philosophically and historically, with religious pluralism. The historical difficulties, summarized by Huston Smith as the fact that the major persecuting religions of the world are monotheistic,(3) stems from the philosophical difficulties monotheism often has with diversity. Not all universalizing religions claim to be uniquely relevant. They claim to be relevantuniversally, rather than relevant only within a specific ethnic context, but they do not make exclusive truth claims or claim that adherents of other religions are doomed to dim futures. By contrast, the monotheisms, especially Christianity and Islam, have been persuaded by the logic that the existence of the one Supreme Being implies only one correct or adequate way of conceptualizing and relating to that deity. Thus monotheistic religions often claim not only to be universally relevant but to be uniquely relevant; they make exclusive truth claims. The exclusivity of these truth claims makes for special difficulties in the pluralistic world. To contrast monotheism's specific mode of universalizing -- the claim to

unique relevance and exclusive truth, even a monopoly on "salvation" -with other styles of universalizing, I will briefly outline the other major variants. Of the world's major religions, only one nonmonotheistic religion, Buddhism, has spread far beyond the culture of its origin. But the great cultures of Asia produced not only monotheism but two other major families of religions, at least potentially universalizable, that sprang from the ethnoreligious base. South Asia has given us Hinduism and Buddhism, in addition to a number of smaller religions. The practice of religious debate flourished in South Asia, often with great acrimony, particularly in intra-Buddhist contexts. But, in the long run, the mainstream position for both Hinduism and Buddhism is that religious diversity is inevitable, beneficial, and necessary because of human diversity. Hinduism has taken this position perhaps more seriously than any other religion. East Asia produced an equally complex and quite different family of religions -- Confucianism, Taoism, Shinto. Here the solution to religious diversity is especially interesting. Everyone, except for religious specialists such as priests, "belongs" to all the religions, calling upon each one for different needs. The idea of exclusive loyalty to one religion is rather foreign and incomprehensible to most people. To return to our focus on monotheism, throughout their history and into the present, monotheistic religions have displayed two attitudes toward other religions. The attitude that is more familiar and popular, the attitude transmitted to me and to many others by mainstream religious institutions of our society, censures other religions, especially those falling into the vague and negative category of "paganism." "Pagan" religions are categorically inferior, apparently because of associations with "polytheism," their use of icons, their reverence for nature and, in many cases, for sexuality and feminine symbolism as well. In some cases, not only "pagan" religions but other monotheistic faiths, or even subsects within one of the monotheistic religions, are censured and evaluated as "idolatrous" and inadequate. Claims for a unique and universal truth, frequent among monotheists, can become quite specific and overwhelmingly exclusive, excluding everyone even slightly different from "us" from felicity and long-term well-being. Such religious ethnocentrism truly parallels racial, ethnic, class, and gender chauvinisms and is, unfortunately, frequently combined with them by those who dislike diversity. Monotheistic religions have also put forth other evaluations of "foreign" religions, whether monotheistic or nonmonotheistic. Judaism has long interpreted the covenant made with Noah after the flood as a universal covenant with all humanity, whether Jewish or non-Jewish, demanding only basic morality rather than complex ethnic codes of behavior or intellectual assent to abstract doctrines. Thus Jews, a powerless minority in the big picture for most recent history, have held to their own ways as

mandatory for Jews, while declaring that "the righteous of all nations have a share in the world to come."(4) Though the powerful monotheistic religions, Christianity and Islam, have perhaps been disadvantaged by their power to reach similar conclusions, one finds tendencies in that direction nevertheless. Islam, in its imperialist heyday, gave preferential treatment to other "people of the Book." More recently, some Jewish and Christian theologians have talked of "multiple covenants"(5) or "anonymous Christians"(6) in an attempt to defuse the claim that the deity of monotheistic religion relates itself favorably only with adherents of one's own version of monotheism or religion. These ideas are attempts to discover ways of understanding that the one universal deity could have been discovered or could have revealed itself more than once. The documents on religious pluralism from the Second Vatican Council also make such an attempt. They include both special statements on Judaism and Islam, monotheistic neighbors, and a general statement on other religions, urging less divisive attitudes and encouraging Christians to recognize truth whenever found in other religions.(7) Nevertheless, both of these solutions to the problem of otherness and pluralism by monotheistic religions fall far short of the mark. In the remaining pages, I will critique each point of view in turn and then suggest a more adequate way of dealing with religious diversity, an approach equally appropriate to monotheistic and nonmonotheistic religions, though more urgently needed by monotheists because of the seriousness of their problems with religious diversity. The first point of view, which censures "paganism" or even other versions of monotheism, is odious especially because it so strongly promotes an "us-them" mentality, arrogance, and xenophobia. Often adherents of this point of view are also quite ill-informed about the religions they so confidently condemn, especially the less-familiar nonmonotheistic "pagan" religions. For example, feminist scholarship has taught me that the so-called pagan religions often utilized feminine symbols and images of deity and fostered women's full participation in religion in a way that monotheistic religions usually do not. Study of various tribal traditions has taught me that reverence for nature is not idolatry. Long years of studying Hinduism and vivid religious experiences in India have taught me that polytheism is far more sophisticated and far less culture-bound than the monotheists ever imagined and that the use of visual metaphors or icons -- so-called "idols" in the misinformed monotheistic critique -- is no more nor no less idolatrous than the reliance on the word and the verbal symbols preferred by the monotheistic religions. Furthermore, the monotheistic religions cannot claim moral superiority. As Huston Smith has pointed out, the major persecuting religions of the world are monotheistic,(8) and their

willingness to persecute is tied directly to their universalistic convictions, especially the conviction that their conceptualization of deity is universally relevant and supreme. On the surface, it might seem that the second reaction to other religions is much more adequate. Regarding other religions as alternate versions of "our" covenant or regarding some members of other religions as "anonymous Christians" might seem much more humane than regarding them as misguided, incorrect, and out-of-date "pagans." It might seem that this theology provides a more inclusive model for understanding the plurality of world religions, including the nonmonotheistic religions. As a stage in the process of coming to an appreciation of religious pluralism, such an understanding has much to recommend it. Nevertheless, though all religions go through this stage after finding the "us-them" position inadequate, problems remain. Upon closer inspection, a position advocating multiple covenants or respect for all people of the book turns out to involve a subtler form of religious imperialism than the more blatant "us-them" position. Typically, as members of one religion begin to enter into the world and worldview of another, seemingly very different, religion, the initial reaction of hostility based on perceptions of difference gives way to feelings of friendliness accompanied by an evaluation that "they're just like us after all." Certainly at a very basic level of common humanity, this conclusion is true and much to be prized and encouraged. Nevertheless, when translated into theological terms, this insight often has an unfortunate imperialistic edge. Put in its most blatant form, a form never actually articulated, the logic of the position is that since "they" clearly are just as human and just as wise and moral as "we" are, they must participate in the same religious universe that "we" do, even if, on the surface, "their" religion seems quite different. Their religion is of divine, not demonic origins, after all. They too have a covenant with the deity, to put this position in its Jewish form. Or they are on a different path to the same goal of enlightenment, to put the position in its Hindu form. Or, to put this position in its best-known form, a Christian form made famous by Karl Rahner, members of other religions are "anonymous Christians."(9) In other words, the central category of our religion also applies to them. They share "our" world and "our" values, even if "they" don't know it. Thus, this position is also a universalizing stance vis-a-vis other religions. However, instead of advocating that others join "us," they are claimed as really, in essence, part of "our" group already, despite differences of theology and values. It might seem mean-spirited to criticize and to parody this position which generously includes the "others" in "our" group. However, the claim that they participate in the categories central to "us" does not allow for genuine pluralism. The claim still elevates one religion above the others

as superior and, of course, that superior religion is "ours." Though such a position seems to be an important stage in the process of coming to a fully adequate philosophy of religious pluralism, it is by no means an ideal conclusion. The philosophy of religious pluralism needed today is much more daring. It goes far beyond the attempt to include "them" in our categories and it also goes far beyond mere tolerance of differences. Genuine pluralism, as I would name this ideal philosophy of religious pluralism, unlike a theory of multiple covenants, anonymous Christianity, et cetera, is fully aware of genuine differences among the world's religions. Nevertheless, there is no need to elevate one religious viewpoint as superior nor to reduce them all to the same thing. This genuine and very real pluralism of religious worldviews and value systems does not cause psychological stress or distress. Rather, there is deep and thoroughgoing appreciation of the different systems; their infinite variety becomes a source of fascination and enrichment rather than a problem. Finally, without trying to create a single religious system out of the plurality of world religions, it becomes possible to be inspired by other religions, to the point that one welcomes and fosters mutual transformation, taking on aspects of other religions that are lacking or weak in one's own. Clearly, this attitude of genuine pluralism is not the norm taught by the religions to their adherents, nor is it an attitude that grows and matures without fostering. Though I am highly critical of the more conventional and traditional attitudes of the world's religions toward religious diversity, I do not think that, for the most part, the kind of attitude I am delineating was possible until recently. Nevertheless, at this point in history, developing an attitude at least of tolerance, if not of genuine pluralism, is no longer a luxury for an intellectual and spiritual elite. But how can such a basic change come about? There is no longer any excuse for religious leaders to perpetuate old attitudes toward religious diversity. Therefore, it is critical that the intellectual and spiritual elite of every religion look into the conditions requiring a response of genuine pluralism, the factors fostering the growth of such an attitude, and the likely impact of genuine pluralism on one's own religious tradition. The leaders of religions, the intellectual and spiritual alike, have no more pressing or relevant agenda before them. In today's conditions, it is not too much to ask all religious specialists and leaders in all religions, sects, and denominations to be well-versed on religion in general. Years of seminary and graduate school training plus continuing pastoral training can surely include something so basic. If the leadership trains itself in genuine pluralism rather than religious ethnocentrism, those who look to them for guidance in attitudes regarding religious diversity would be more likely to develop tolerance, if not deep sophistication, about these issues. On the other hand, in many instances the rank and file of the

religions are already more tolerant and more interested in religious diversity than are their leaders. Whoever leads and whoever is led, the journey should commence. Developing from indifference or intolerance to tolerance to genuine pluralism is a long, subtle, perhaps never-ending, process of growth analogous to individuation or other tasks in the creative fulfillment of human potential. Though this journey is so far less explored, I believe one can map out some guideposts. The external conditions necessitating genuine pluralism are simple. We live in a world in which there will be many religious, as well as many economic and political systems. No matter what attitude people may have about others who have different symbols and values, those different symbols and values simply are not going to go away or merge into one system. Such has always been the case, of course, but previously with greater isolation and ignorance, such attitudes of superiority and ethnocentrism could persist without becoming too dangerous. Such conditions no longer prevail, However, the sheer unyielding facticity of religious pluralism in the global village is, by itself, not enough to create genuine pluralism. More subtle individual and internal psychological factors are also critical. First among these critical internal conditions is knowledge and willingness to know. Ignorance about the various religious systems, whether resulting from lack of available information or from sheer refusal to learn the available information, cannot foster genuine pluralism. Instead, ignorance fosters vague and stereotypical impressions of foreign beliefs and symbols, leading only to increased feelings of superiority. To counteract these tendencies, it is necessary to develop empathy, to enter into the mental and spiritual universes of others, thereby discovering their internal logic, coherence, and reasonability. Such empathy, growing out of the accurate information about the world's religions readily available today, is almost instantaneously effective in fostering attitudes of genuine pluralism. With proper motivation, and encouragement rather than discouragement from religious leaders, anyone can develop these skills. Certainly the tools -- accurate and empathic accounts of the world's religions and good teachers of the various traditions -- are readily available. The motivation to use these tools would be enhanced if the various traditions encouraged, or preferably required, their own members to avail themselves of these tools as part of the process of religious training. Such a basic reformation of sectarian religious education is greatly to be encouraged. The second complex of internal factors necessary for developing a genuinely pluralistic attitude is even more critical. Feelings of hostility

and superiority, typical and traditional reactions upon encountering religious difference and divergence, result from deep insecurity. As Wilfrid Cantwell Smith pointed out in an important and influential article on Christianity and diversity, people often fear that if a different point of view makes sense, then "ours" must be inadequate. Therefore, people often feel that they have a vested interest in demonstrations of the wrongness or inferiority of divergent positions.(10) However, on both logical and psychological grounds, such inferences are unnecessary. A clearer understanding of the nature and limits of religious language frees one from the logical impasse of assuming that if one religious belief makes sense, others that are different must, therefore, be wrong. More importantly, it is not necessary to build a psychology of self-esteem on the basis of denigrating difference. In fact, genuine selfesteem cannot be built on that basis. It grows out of a self-existing and noncompetitive comfortableness with one's self."(11) When selfacceptance is manifest, divergence is intriguing rather than threatening. Therefore, it is important for the various religions to foster profound love of their own tradition in their members -- a love mature enough not to be based on competitiveness and not to foster insecurity as a response to difference. It is critically important to be clear about the psychological truth that genuine pluralism is not based on and does not demand a diminished love of and joy in one's own religious and spiritual perspective. It only undercuts chauvinism and ethnocentrism -- the pseudo-love of the spiritually immature. As the attitude of genuine pluralism matures, certain conclusions about the nature of religious claims become ever more compelling. The human initiative in formulating religious beliefs becomes ever more obvious and with that realization comes an ever clearer awareness of the cultural relativity that conditions all religious claims. These facts about religious symbols and belief systems encourage the conclusion that universal truth claims make little sense and should be abandoned. Since these implications of genuine pluralism go against the grain of conventional attitudes, it is important to examine them in more depth. Most religions, of course, claim some transcendent origin, an origin of seemingly greater significance and relevance than mere human creativity and responsiveness to the open and luminous quality of full human experience. A nonhuman origin also meshes neatly with universal truth claims and the wish to be widely relevant. If "our" religion has a nonhuman, divine source, then obviously it is relevant not just for "us," but for everyone. However, given our present state of knowledge about world religions, it is no longer possible to maintain a belief in a unique and nonhuman origin for "our" religion. The way in which symbols are embedded in culture and history, the way in which they are responses to

experience, and the way they mirror those who proclaim them are too obvious to permit a claim that "ours" are somehow exempt from these processes. Upon further reflection, it becomes clear that acknowledging the human component and the cultural relativity of religion in no way threatens the validity or relevance of religion in general or of any specific religion. Beneath all the culturally relative and culture-bound symbols or beliefs and at the heart of the human creativity and responsiveness generating religious symbols and beliefs is That Which stimulates such responses. Adequately communicated by no symbols, pointed to be them all, this Sacred Something (for lack of any other less inadequate terminology) is not diminished or made irrelevant by the recognition that it does not and cannot be entered into human discourse except by means of human, culturally relative symbols. Sometimes, it is questioned, in the face of the logic that universal truth claims are inappropriate, how one can feet passionately committed and connected to something conceded to be less than the universal truth. Whence, then, comes the ardor to study and practice intensely, to endure persecution, if need be? Would one DO that for a humanly created and culturally relative symbol system not claimed to be the only, the ultimate truth? Does not religious conviction depend on the feeling that one's religion is uniquely worthwhile? This very real question has perhaps best been dealt with by Krister Stendahl, former dean of Harvard Divinity School and bishop of Stockholm, in his discussions of how Christians could deal with claims about Jesus as the only savior in an age of pluralism and multiple truths. Stendahl, and many others, suggest a distinction between various modes of language, especially between metaphysical or scientific language and poetic, relational language in religious claims. Sometimes one kind of language is appropriate, but in other contexts, the other kind of language is more appropriate. Stendahl suggests an analogy. As paraphrased by Paul Knitter: Exclusivist. . . language is much like the language a husband would use of his wife (or vice versa): "You are the most beautiful woman in the world. . . you are the only woman for me." Such statements, in the context of the marital relationship and especially in intimate moments, are certainly true. But the husband would balk if asked to take an oath that there is absolutely no other woman in the world as beautiful as his wife or no other woman whom he could possibly love and marry. That would be using a different kind of language in a very different context.(12)

In the same way, one could realize that language about the "only deity" or "only savior" is appropriate for the intimacy of private devotions and communal liturgy while recognizing that such language is utterly inappropriate for the courtroom of the philosophical, systematic, and rational study of religious diversity. The context in which the language is spoken dictates whether poetic or empirical language is appropriate. Because one realizes that religious language is essentially a poem, not a scientific, empirical description, one can easily feel that one's religion is the only one to which one could be committed without believing that it is therefore universally relevant. That principle applies not only to religions as wholes, but, even more importantly, to the cherished and central beliefs or symbols within a religion. Up to this point, the attitude of genuine pluralism may seem only to be a requirement, even a burdensome requirement, of modernity, of life in the global village, and of our accurate knowledge about other religions. However, I would like to conclude my comments on religious diversity with the suggestion that genuine pluralism offers much, much more by way of fundamental enrichment, both of life in general and of the religious life. Development toward this final stage of enrichment can be mapped out. The beginning of the process is the development of tolerance, of some notion that one must live and let live religiously, accompanied by the conclusion that such nonaggression is more workable than constant judgment of and competition between religions, whether ideological or physical. Though I am critical of tolerance as an insufficient method, by itself, for dealing with religious pluralism, nevertheless, the development of religious tolerance in the Western religions, and especially in Christianity, was a major breakthrough. I criticize the adequacy of mere tolerance because, so often, it is based on nothing more profound than sheer inability to exert influence over or to dominate other religions. Even less adequate is the tolerance based on indifference to religion altogether, on lukewarm perfunctory religious membership and lack of religious passion. Nevertheless, without the foundation of tolerance, further approaches to religious pluralism could not develop. Perhaps the most critical step in this process is the transition from tolerance to curiosity. Rather than merely tolerating other points of view, one becomes curious about them and begins to explore and to investigate them empathetically. Because this step in the process of fostering and developing genuine pluralism is so very important, every means of encouraging this basic transformation should be utilized, both by the various religions and as a matter of basic social policy.

Once curiosity begins to develop, the rest of the process will usually follow, though for some people it may take many years. Curiosity brings with it two critically important attitudes. First, fundamental openness and lack of rigidity develop. Maintaining barriers and fixed ideas becomes unnecessary; growth and development, even radical changes in religious outlook, become intriguing possibilities rather than threats. Furthermore, one wants to understand the other accurately, with empathy, from the inside. Stereotypes, misinformation, and attitudes of superiority become painful. Because of these two attitudes, serious study of the other, including interreligious dialogue, becomes important. Such accurate and empathic understanding of the other is the basis of the next important development -- deep and warm appreciation. This appreciation is two-faceted. On the one hand, once one understands other religions on their own terms, it is difficult not to appreciate them. They are so fascinating, so coherent internally, so rich, and, usually, so compelling. As one begins to grow toward genuine pluralism, this kind of attraction is not threatening because one realizes that appreciation does not demand personal faith commitment to what one appreciates. Variety and difference among religions is the norm and a precious resource, not aproblem. The other facet of appreciation is not so obvious and is not anticipated by most people at the beginning of their journeys toward genuine pluralism. However, once one really begins to understand other religions accurately, one is in a position also to appreciate one's own religion much more fully. This appreciation results from having the basis to understand the uniqueness and specificity of one's own tradition. Because one sees so clearly that it is not the only rational or compelling option, one can see what specifically about one's own tradition is personally relevant and compelling. A famous comment, made by Max Muller, the founder of the discipline of history of religions, puts the matter very accurately. "To know one religion is to know none."(13) One cannot understand the specificity and uniqueness of one's religion if one does not have the basis for comparison. Of course, the appreciation of the other prevents these comparisons from becoming invidious comparisons seeking to assign relative worth. Differences are simply noted and appreciated as part of the vividness of the phenomenal world. At this point, the next, and perhaps the last stage in the development of genuine pluralism can occur. Based on both appreciative commitment to one's own tradition and on accurate, empathetic understanding of other traditions, a process of mutual transformation can begin. Discussed most thoroughly by process theologian John Cobb, this concept is becoming important to the process of interreligious dialogue, especially BuddhistChristian dialogue.(14) However, the process as such has much wider

applicability. Since, as Huston Smith, among others, has pointed out, every religion has strengths and weaknesses,(15) appreciative understanding promotes a process of mutual transformation in which study of the other, and especially dialogue with the other, actually changes one's self. One begins to incorporate aspects of the other into one's self. This process, it must be pointed out, is not the same as syncretism, a futile attempt to create a new religion by selecting the "best" features of the existing religions. Mutual transformation does not result in new religions or in one universal syncretistic religion, but in the enrichment of the various traditions that results when their members are open to the inspiration provided by resources of others. How much more satisfying intellectually and ethically than mere tolerance or religious ethnocentrism and chauvinism!

Notes

1. [Back to text] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane (New York: Harper and Row, 1957), 29-32. 2. [Back to text] Milton C. Sernett, "Religion and Group Identity: Believers as Behavers," in Introduction to the Study of Religion, ed. T. William Hall (New York: Harper and Row, 1978), 217-27. 3. [Back to text] Huston Smith, "Accents of the World's Religions," in Introduction to the Study of Religion, ed. T. William Hall (New York: Harper and Row, 1978), 37. 4. [Back to text] Cited in A Rabbinic Anthology, selected and arranged, with comments and introductions by C. G. Montefiore and H. Lowe (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1960), 603, 556. 5. [Back to text] For a review of this and other Jewish positions on Jewish attitudes towards other religions, see Harold Kasimow, "Abraham Joshua Heschel and Interreligious Dialogue," Journal of Ecumenical Studies 19 (Summer 1981): 423-34; Abraham Joshua Heschel, "No Religion Is an Island," in Disputation and Dialogue, ed. F. E. Talmage (New York: KTAV, 1975), 343-59. 6. [Back to text] Karl Rahner, "Christianity and the Non-Christian Religions," in Christianity and Other Religions, ed. John Hick and Brian Hebblethwaite (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980), 52-79; see especially 75-79. 7. [Back to text] "A Declaration on the Relations of the Church to NonChristian Religions," Vatican II, in Christianity and Other Religions: Selected Readings,ed. John Hick and Brian Hebblethwaite (Philadelphia:

Fortress Press, 1980), 80-86. 8. [Back to text] Huston Smith, "Accents of the World's Religions," in Introduction to the Study of Religion, ed. T. William Hall (New York: Harper and Row, 1978), 37. 9. [Back to text] Rahner, "Christianity and the Non-Christian Religions," 75-79. 10. [Back to text] Wilfrid Cantwell Smith, "The Christian in a Religiously Plural World," in Christianity and Other Religions, ed. John Hick and Brian Hebblethwaite (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1980), 9899. 11. [Back to text] For this insight and for its articulation, I am deeply indebted to my many years of experience with Buddhist meditation and its healing effects. Though the verbal articulation is less important than the actual experience of meditation practice, generally one speaks of uncovering self-existing and nondualistic goodness. This goodness simply is without reference to comparison and competitiveness. Furthermore, it engenders all-encompassing friendliness without reference to whether the other is similar or different. Because this understanding is so experiential, it is difficult to cite sources for it and impossible to pin the citations to a few pages. For something of the flavor of basic Buddhist meditation and its effects, I recommend three books: Joseph Goldstein, The Experience of Insight (Boston: Shambhala Press, 1985), Ozel Tendzin, Buddha in the Palm of Your Hand (Boulder, Colo.: Shambhala, 1982), and Chogyam Trungpa, Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior (Toronto and New York; Bantam Books, 1986). 12. [Back to text] Paul Knitter, No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes toward the World Religions (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1985), 185. 13. [Back to text] Quoted in William E. Paden, Religious Worlds: The Comparative Study of Religion (Boston: Beacon Press, 1988), 38, from F. Max Mueller,Lectures on the Science of Religion (New York: Charles Scribner and Co., 1872), 10-11. 14. [Back to text] John Cobb, Beyond Dialogue: Toward a Mutual Transformation of Buddhism and Christianity (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1982); see especially 47-54. 15. [Back to text] Huston Smith, "Accents of the World's Religions," in Introduction to the Study of Religion, ed. T. William Hall (New York:

Harper and Row, 1978), 127-40.

Copyright of Cross Currents is the property of Association for Religion & Intellectual Life and its content may not be copied without the copyright holder's express written permission except for the print or download capabilities of the retrieval software used for access. This content is intended solely for the use of the individual user. Source: Cross Currents, Fall 1999, Vol. 49 Issue 3.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 1 Globalization of ReligionDokument6 Seiten1 Globalization of ReligionLorenzo Esquivel BallesterosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Six Degrees of Separation: A Curriculum on World ReligionVon EverandSix Degrees of Separation: A Curriculum on World ReligionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living in A Religiously Plural World - Problems and Challenges For Doing Mission in Asia K.C. AbrahamDokument9 SeitenLiving in A Religiously Plural World - Problems and Challenges For Doing Mission in Asia K.C. AbrahamMirsailles16Noch keine Bewertungen

- America and the Challenges of Religious DiversityVon EverandAmerica and the Challenges of Religious DiversityBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Origins and Diffusion of World ReligionsDokument9 SeitenOrigins and Diffusion of World ReligionsAngelyn LingatongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding World Religions in 15 Minutes a DayVon EverandUnderstanding World Religions in 15 Minutes a DayBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (6)

- Xyrill Group4.GE3Dokument22 SeitenXyrill Group4.GE3WILLIAM DAVID FRANCISCONoch keine Bewertungen

- Grounding Our Faith in a Pluralist World: with a little help from NagarjunaVon EverandGrounding Our Faith in a Pluralist World: with a little help from NagarjunaBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (3)

- EATWOT-Religions, Pluralism and PeaceDokument9 SeitenEATWOT-Religions, Pluralism and Peacesalomon44Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Ways of Looking at Religion: The Major NarrativesVon Everand7 Ways of Looking at Religion: The Major NarrativesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jose Rizal University Senior High School DivisionDokument7 SeitenJose Rizal University Senior High School DivisionVicky PungyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges of Religious PluralismDokument9 SeitenChallenges of Religious PluralismtughtughNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Religious Pluralism: Perspectives from Religious Studies and TheologyVon EverandUnderstanding Religious Pluralism: Perspectives from Religious Studies and TheologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Religion and GlobalizationDokument13 Seiten9 Religion and GlobalizationMiguel Anjelo OpilacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Many True ReligionsDokument22 SeitenMany True ReligionsLuis Marcos TapiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Studies Approach Introduction AnswerDokument12 SeitenCultural Studies Approach Introduction AnswerRafael FornillosNoch keine Bewertungen

- AAR - Why Study ReligionDokument18 SeitenAAR - Why Study Religioncsy7aaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problems and Prospects of Inter-Religious Dialogue: Anastasios (Yannoulatos)Dokument7 SeitenProblems and Prospects of Inter-Religious Dialogue: Anastasios (Yannoulatos)Escritura Académica100% (1)

- Thesis For World Religion PaperDokument5 SeitenThesis For World Religion Paperdebradavisneworleans100% (3)

- 06 Chapter1Dokument74 Seiten06 Chapter12003vinayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Religion Does More Harm Than GoodDokument11 SeitenReligion Does More Harm Than GoodCai Peng FeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worldview and CultureDokument11 SeitenWorldview and Culturehimi oumaimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Religions, A Delusion???: Alex KinnetDokument4 SeitenReligions, A Delusion???: Alex KinnetAlexNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Ninian Smart DimensionsDokument8 SeitenFrom Ninian Smart DimensionsAnnabel Amalija Lee100% (1)

- Methodologial Assumptions and Analytical Frameworks Regarding ReligionDokument5 SeitenMethodologial Assumptions and Analytical Frameworks Regarding ReligionParkash SaranganiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Culture Versus Our FaithDokument50 SeitenOur Culture Versus Our FaithIfechukwu U. IbemeNoch keine Bewertungen

- ReligionDokument2 SeitenReligionlozaha70Noch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization Lesson 10-15Dokument60 SeitenGlobalization Lesson 10-15Venven PertudoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Positive & Negative Effects of ReligionDokument70 SeitenPositive & Negative Effects of ReligionlucilleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization and Cross Cultural Understanding.dDokument17 SeitenGlobalization and Cross Cultural Understanding.dDanielle ReginaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 9 The Globalization of ReligionDokument31 SeitenLesson 9 The Globalization of ReligionAldrin ManuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 9 The Globalization of ReligionDokument55 SeitenLesson 9 The Globalization of ReligionMarie DelrosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difference Between Religion and CultureDokument4 SeitenDifference Between Religion and CulturePrashant TiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- HILONGO - MIDTERM ACTIVITY # 2 Globalization of ReligionDokument2 SeitenHILONGO - MIDTERM ACTIVITY # 2 Globalization of ReligionHILONGO, RaizelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position Comparison - Why All Religions Are Ultimately The SameDokument6 SeitenPosition Comparison - Why All Religions Are Ultimately The Sameapi-338165809Noch keine Bewertungen

- ACTIVITY 3-Collaborative LearningDokument9 SeitenACTIVITY 3-Collaborative LearningOlga LuciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LSO216.1 - Religion and Culture in Canada (S20)Dokument15 SeitenLSO216.1 - Religion and Culture in Canada (S20)Thanusan RaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Globalization of ReligionDokument3 SeitenThe Globalization of ReligionJhonsel MatibagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3: Understanding Religious DiversityDokument7 SeitenLesson 3: Understanding Religious DiversityJulius de la CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization of Religion GEC TCW FinalDokument30 SeitenGlobalization of Religion GEC TCW FinalJannen V. ColisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dafney ContempoDokument12 SeitenDafney ContempoMiljane PerdizoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cworld1 Midterms: The Globalization of ReligionDokument13 SeitenCworld1 Midterms: The Globalization of ReligionJAEZAR PHILIP GRAGASINNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act 3Dokument3 SeitenAct 3Arlene BlasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anne Marie B. Bahr-Religions of The World-ChristianityDokument239 SeitenAnne Marie B. Bahr-Religions of The World-ChristianityGheorghe Mircea67% (3)

- Divine IntersectionsDokument21 SeitenDivine IntersectionsMeer FaisalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3.possitive and NegativeDokument15 SeitenChapter 3.possitive and NegativeMaRvz Nonat MontelibanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction Paper2Dokument3 SeitenReaction Paper2api-252393431Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Module SLG 3Dokument4 SeitenReading Module SLG 3Julie ArnosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative Essay - Religion: Boon or Bane?Dokument6 SeitenArgumentative Essay - Religion: Boon or Bane?chastineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evolution of Religion: Atapuerca Neanderthals Hominids Grave GoodsDokument18 SeitenEvolution of Religion: Atapuerca Neanderthals Hominids Grave GoodsDevesh ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methodologial Assumptions and Analytical Frameworks Regarding ReligionDokument5 SeitenMethodologial Assumptions and Analytical Frameworks Regarding Religionana kNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Search of Certainties: The Paradoxes of Religiosity in Societies of High ModernityDokument10 SeitenIn Search of Certainties: The Paradoxes of Religiosity in Societies of High ModernityAlexandr SergeevNoch keine Bewertungen

- Positive Negative Effects of ReligionDokument15 SeitenPositive Negative Effects of ReligionJoshua Cruz71% (7)

- Convergence of Religions Kenneth OldmeadowDokument11 SeitenConvergence of Religions Kenneth Oldmeadow《 Imperial》100% (1)

- Is Religion A Force For GoodDokument3 SeitenIs Religion A Force For GoodRoberta ŠareikaitėNoch keine Bewertungen

- Globalization ReligionDokument2 SeitenGlobalization ReligionPaul Fajardo CanoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teach 3Dokument9 SeitenTeach 3JagdeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE ELEC 3 Module 1Dokument7 SeitenGE ELEC 3 Module 1Mae Arra Lecobu-anNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education Durkheim ExcerptsDokument2 SeitenEducation Durkheim ExcerptsCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- And Global Poverty"Dokument3 SeitenAnd Global Poverty"Carlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- El Salvador Peace ProcessDokument64 SeitenEl Salvador Peace ProcessCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- COLOMBIA: Impunity Still Surrounds Palace of Justice TragedyDokument4 SeitenCOLOMBIA: Impunity Still Surrounds Palace of Justice TragedyCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- BuddhismDokument41 SeitenBuddhismCarlos Perez100% (1)

- The Making of The Golden BoughDokument23 SeitenThe Making of The Golden BoughCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education Social Class WagesDokument45 SeitenEducation Social Class WagesCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resnick Democratic Safety ValvesDokument17 SeitenResnick Democratic Safety ValvesCarlos PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authority Must Be ObeyedDokument5 SeitenAuthority Must Be Obeyedoh_frabjous_joyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paternity Leave and Solo Parents Welfare Act (Summary)Dokument9 SeitenPaternity Leave and Solo Parents Welfare Act (Summary)Maestro LazaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- PISA2018 Results: PhilippinesDokument12 SeitenPISA2018 Results: PhilippinesRichie YapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum VitaeDokument2 SeitenCurriculum VitaeCyra DonatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Folk Dances With Asian Influence (BINISLAKAN) : Kabuki Wayang Kulit Peking Opera Nang Puppet ShowDokument4 SeitenPhilippine Folk Dances With Asian Influence (BINISLAKAN) : Kabuki Wayang Kulit Peking Opera Nang Puppet Showanjilly ayodtodNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAQ - Yayasan Peneraju Sponsorship For Graduates Sponsorship Programmes 2023Dokument8 SeitenFAQ - Yayasan Peneraju Sponsorship For Graduates Sponsorship Programmes 2023Fuad AsriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening Practice Test 2Dokument2 SeitenListening Practice Test 2Alex Rodrigo Vilamani PatiñoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department OF Education: Director IVDokument2 SeitenDepartment OF Education: Director IVApril Mae ArcayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JwjejejejejjDokument1 SeiteJwjejejejejjstok stokNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMI W HFA STA. CRUZ ES 2022 2023Dokument105 SeitenBMI W HFA STA. CRUZ ES 2022 2023Dang-dang QueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument8 SeitenChapter 2Zyrome Jen HarderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronics PDFDokument41 SeitenElectronics PDFSumerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan in Physical Education and Health GRADE 9Dokument4 SeitenLesson Plan in Physical Education and Health GRADE 9Ina Jane Parreño SalmeronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade Six 4Ps Reading AssessmentDokument8 SeitenGrade Six 4Ps Reading AssessmentMarilyn Estrada DullasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cps High School Biography ProjectDokument6 SeitenCps High School Biography Projectapi-240243686Noch keine Bewertungen

- Call For Admission 2020 Per Il WebDokument4 SeitenCall For Admission 2020 Per Il WebVic KeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- FS Module 1 16Dokument178 SeitenFS Module 1 16Michael SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- AchievementsDokument4 SeitenAchievementsapi-200331452Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fun Learning With Ar Alphabet Book For Preschool Children: SciencedirectDokument9 SeitenFun Learning With Ar Alphabet Book For Preschool Children: SciencedirectVikas KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inquirie S, Investig Ation & Immersi OnDokument56 SeitenInquirie S, Investig Ation & Immersi OnPaolo MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity 2 Legal AspectDokument3 SeitenActivity 2 Legal Aspectzaldy mendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

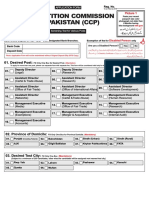

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NDokument4 SeitenCompetition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NMuhammad TuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus Advanced Cad Cam Spring 2013Dokument6 SeitenSyllabus Advanced Cad Cam Spring 2013api-236166548Noch keine Bewertungen

- EAPP - Q1 - W1 - Mod1 - Divisions of City School Manila 11 PagesDokument11 SeitenEAPP - Q1 - W1 - Mod1 - Divisions of City School Manila 11 Pageswriter100% (7)

- Nep in Open Secondary SchoolDokument7 SeitenNep in Open Secondary Schoolfpsjnd7t4pNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 96 Philosophy of Education: Professor: Lailah N. JomilloDokument14 SeitenEd 96 Philosophy of Education: Professor: Lailah N. JomilloRoginee Del SolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Interactionist TheoryDokument13 SeitenSocial Interactionist TheorySeraphMalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohamed Youssef: Control EngineerDokument2 SeitenMohamed Youssef: Control EngineerMohamed Youssef100% (1)

- Why Adults LearnDokument49 SeitenWhy Adults LearnOussama MFZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management PDFDokument251 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management PDFkoshyligo100% (2)