Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Wegelin Document On American Taxes and Assets

Hochgeladen von

ZerohedgeOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wegelin Document On American Taxes and Assets

Hochgeladen von

ZerohedgeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Investment Commentary No.

265 August 24, 2009

Farewell America izers, as frequently stated in the Swiss media,

among others. It is astounding, and this is the

second interesting observation, how completely

1. A moral issue? naturally those who claim the moral high-ground

The agreement between the USA and Switzer- rush to join forces with the authorities and their

land under which Switzerland is to provide ad- financial requirements. At the risk of once again

ministrative assistance with regard to 4,450 UBS winding up certain specialists in business ethics,

clients suspected of tax fraud is, in our view, re- let us briefly recall the sort of tax authorities we

markable in three ways. Firstly, we note the way are dealing with, and the sort of state they serve: a

both parties are dressing it up in the aftermath of country that, over the last 60 years, has unques-

the battle. Everyone is talking of a “success”. The tionably been one of the most aggressive nations

IRS, the American tax authority, surely rightly, in the world. The USA has fought by far the larg-

for it has got what it wanted, namely access to a est number of wars, sometimes with, but mostly

large number of specific client names, combined without a UN mandate. It has broken the interna-

with persisting uncertainty on the part of all the tional laws of war, maintained secret prisons, and

others as to whether they are among those names. fought an absurd war against drugs, with serious

The UBS is happy not to have to pay another consequences both abroad (Columbia, Afghani-

fine, and to be rid of the heavy burden of legal stan) and at home (according to reliable sources,

proceedings. And the Swiss government regards it the tentacles of the narcotics mafia now reach

as a success inasmuch as from their perspective well into political circles). With breathtaking

the agreement preserves the rule of law and offers moral duplicity, the USA maintains enormous

the clients affected the possibility of legal re- offshore havens in Florida, Delaware and others

course to the federal administrative court. of its states. The moralizers have joined sides with

a nation that still makes extensive use of the

But there are also losers, of course. These are the death penalty, and that has a legal system under

people affected, who must now expect legal pro- which lawyers can get rich on the misfortunes of

ceedings against them as suspected tax cheats, their clients. Liability cases often end in verdicts

and who had, until relatively recently, been prom- with exorbitant damages, which makes business

ised that precisely this would not happen. Prom- activity extremely risky, for medium-sized enter-

ised by whom? By the bank concerned (among prises in particular. The moralizers provide intel-

others), which had generously interpreted and lectual support for a country that allows its infra-

intensively exploited an explicit gap in the 2001 structure to collapse, and then stuffs convicts into

“Qualified Intermediary” (QI) agreement; by the hopelessly overfilled jails, after what are not in-

supervisory authorities, which were fully cogni- frequently dubious proceedings. They fund a

zant of all this activity, but never questioned it; by nation that tolerates – or rather, causes – regular

the Swiss government, which only a few months crises in the global financial system that it man-

ago had spoken of the “brick wall” that foreign ages. A country whose underclass enjoys neither

authorities would encounter, were they to attack the benefits of an adequate education, nor a half-

Swiss banking secrecy – for example through way functional healthcare system; a country

fishing expeditions, such as an application for whose economic system is increasingly inclined to

administrative assistance against several thousand overconsumption, and in which saving and invest-

clients. Promises, connivance, a pretence of reso- ing have increasingly become alien concepts, a

lute behaviour – and now collapse. The appear- situation that has undoubtedly been one of the

ance of success conceals the reality of a breach of driving forces behind the current recession, with

trust. all its catastrophic consequences for the whole

Trust: is this the right word at all for something so world.

disgraceful as tax evasion, or even tax fraud? Those who wish to wield the sword of morality

Serves them right, these bloated capitalists, if they against tax evaders cannot avoid facing some

land in the dock! This is the position of the moral- critical questions with regard to the morality of

W EGELIN & C O .

resource allocation. Were such questions to be Things are different under Anglo-Saxon law.

excluded, we would be left with nothing but the There is no forced heirship, so American inheri-

issue of just taxation, which also arises, as we well tance tax is levied on the “estate”; that is, the

know, when, in Sicily, one baker must make a physical goods, such as property, goods and chat-

contribution to the honourable society, and an- tels, and securities. If they are US securities, then

other not … It is more productive, particularly in they are liable to tax, regardless of the final domi-

matters of taxation, to leave morality aside, and cile or main place of residence of the deceased.

to take a non-judgmental view of tax liability, the US securities are basically defined as securities

meeting of obligations, and, if need be, the vari- issued in the United States, such as the stock of

ous forms of evasion, as givens resulting from the American companies like Apple, General Electric

prevailing legislation and its enforceability. or Pfizer and US funds and US bonds, in particu-

Which brings us to the third thing that seems lar Treasury bills. American inheritance tax law

remarkable. What exactly was the “prevailing makes specific reference to both US citizens (in-

legislation”? And what about its enforceability? cluding, particularly, US citizens resident abroad)

In 1996, the USA concluded a new double taxa- and “non-resident aliens”. These latter are for-

tion agreement with Switzerland, which, among eigners with no permanent residence in the

other things, regulated the conditions for adminis- United States; in other words, all non-Americans

trative assistance in matters of taxation. Switzer- in possession of US securities.

land agreed to provide assistance with regard to American inheritance tax rates are variable, with

“tax fraud and the like”. In other words, the ex- the top rate at 45 percent. Significant exemptions,

tension of the concept of “tax fraud” had long of over 1 million US dollars, are allowed for US

been pre-programmed; the USA had to wait for citizens; the limit for non-Americans is 60,000 US

its enforcement only until Switzerland had appar- dollars, unless there is a double taxation agree-

ently, and perhaps in reality, been driven into a ment setting a higher limit. For Switzerland, the

corner by the activities of the accident-prone limit is calculated on the basis of the double taxa-

UBS. In fact, truth to tell, we should have known: tion agreement of 1951, based on the proportion

Swiss banking secrecy with regard to the USA of the entire estate represented by the assets in

was well and truly relativized not in 2009, but the United States. To claim the allowance, the

already in 1996. “estate” – that is, in continental terms, the heirs –

What we need to do now, sine ira et studio, (and must disclose the entire, global legacy to the IRS.

putting aside all politically motivated window- On account of the IBM shares that he was so

dressing, all genuine, or merely nominal, moral attached to, the children of the late Hans Rüdi-

issues) is to analyze the situation, draw conclu- sühli of Melchnau must file with the IRS and

sions and, where necessary, act upon them. This is present a valuation of all other family assets.

exactly what we intend to do in what follows, by There is a remarkable lack of double taxation

taking a closer look at two important components agreements with the countries of Latin America,

of American tax law. And, surprise, surprise; the Asia and the Middle East. Mr Abdullah of Dubai,

next round of fiscal enforcement staged by the let’s say, a typical owner of treasuries, industrial

Americans will be devoted not to the American bonds and GM shares, is liable to American in-

super-rich, but to non-Americans who never in heritance tax on his decease. Not his problem, but

their lives had any intention of evading taxes. it may well become one for his 12 sons, Omar,

Yakub and all.

Or maybe not? For he had placed his securities in

2. Hans Rüdisühli and Muhammad Abdullah: an institutional structure, a trust or a company

liable to inheritance tax? domiciled on one of the Caribbean islands – and

To get some idea of how the inheritance tax of a institutions cannot die, can they? Indeed not.

foreign state can become a serious problem for However, the Americans are increasingly going

third parties, we need to start with a fundamental over to regarding such structures as look-through

difference between continental and Anglo-Saxon entities, and trying to get access to the bene-

inheritance law. On the continent, the view pre- ficiaries and their tax liabilities.

vails that the logical recipients of assets left by the Another common objection: it’s impossible any-

deceased are their descendants. Accordingly, way. How on earth can the IRS make the connec-

continental inheritance law provides for forced tion between a US security and a deceased for-

heirship, whereby a portion of the estate is legally eigner? The USA is not even capable of register-

required to be left to close relatives. Under such a ing its own residents, so how should it be able to

system, it is not difficult to see where any taxation control the rest of the world? Simple answer: it

of the inheritance should occur: with these heirs.

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 2

W EGELIN & C O .

doesn’t have to. Rather, American inheritance tax ment was, though, monitored by a special audit

law focuses on the executor. If there is no execu- following a process laid down by the US tax au-

tor, the role is fulfilled by the custodian bank, thorities. Our bank was among the signatories to

which is liable for the tax due. In order to exclude the agreement from the start and passed the sub-

this liability, the American custodians of foreign sequent audits, in 2002 and 2007, with flying col-

banks will go over to requiring their partners ours.

abroad to freeze the estate when one of their There are three definitions in this QI agreement

clients dies. that are of decisive importance: that of a US per-

Final objection: it was a dead letter for foreigners son, that of a US security, and that of a legal en-

anyway. Yes indeed. But with the revised provi- tity belonging wholly or in part to a US person.

sions of the Qualified Intermediary agreement, The definition of a US security is fairly unprob-

the USA will require the signatory banks to en- lematic, in that it is effectively determined by the

able an American auditor to control their compli- retention of the withholding tax by the custodian.

ance with the agreement, which entails giving The other two definitions, however, have caused,

such auditors access to all files, including client and continue to cause, almost insurmountable

data. This will create the means of directly linking problems for QIs, and thus generate considerable

US securities with non-American owners. Any- legal uncertainty.

one who believes that this will not soon result in Sadly, it is entirely unclear who actually counts as

obligatory reporting by the US auditor is as naive a US person and who does not. In addition to the

as those who failed to realize that “fraud and the clear case of US citizens resident in the USA, the

like” would eventually be interpreted to the al- American understanding of the category also

most unlimited advantage of the tax authorities. includes foreigners living in the USA, those in

An act passed in 2001 by the previous President possession of a social security card, holders of a

Bush envisaged a “sunset clause” for the then “green card”, US citizens not resident in the

controversial but reintroduced inheritance tax. USA, and also those who pass the so-called “Sub-

Unless extended, the Estate Tax would expire in stantial Physical Presence Test”. This “Presence

2010 and, if not reformed, come into effect again Test” has a particularly delightful design: it is

on 1 January 2011. The Obama administration is passed when someone has been in the USA for at

currently working not merely on an extension, but least 31 days in the current year and a total of 183

on making the law stricter with regard to recog- days over a period of three years; in the first year

nized loopholes. The possibility of further un- the days count for 1/6, in the second for 1/3, and

pleasant surprises can certainly not be ruled out. in the third year they are counted full. By this

definition, a student, perhaps Muhammad Abdul-

lah’s son Omar, who is doing an MBA at Har-

3. A “qualified extended arm” vard, very probably counts as a US person. The

Next, we need to look more closely at the already- problem is that the QI has to know whether he

mentioned Qualified Intermediary agreement. In does or not. For the agreement has turned the QI

2001 the USA introduced a new withholding tax into the extended arm of the American tax au-

system, with the aim of avoiding the complicated thorities.

and expensive reimbursement of tax levied on Even trickier is the question of how far the bene-

those not liable to taxation, and thus to give for- ficiaries of legal entities are liable to withholding

eigners easier access to the American capital mar- tax. Clearly liable, according to the text, are active

ket, and also of obliging US persons with securi- businesses; an American company holding securi-

ties deposited with intermediaries whose coun- ties in Switzerland, for example. Trusts, institu-

tries had no automatic exchange of information tions and foundations are exempt if they meet

with the USA to include all their US holdings in certain – naturally highly complex – conditions.

their tax declarations. This was done by imposing This was probably the trap in which the UBS

a withholding tax of 30 percent, which US persons clients were caught. Once the trap had closed, the

could avoid entirely by full disclosure, and non- American tax authorities shouted “Abuse, fraud

US persons could avoid in part or, depending on (and the like…)!” They set the trap themselves.

the double taxation agreement, entirely, by self-

declaration to the Qualified Intermediary. Matters become really awkward when an impec-

cably non-American legal entity suddenly be-

The 2001 QI agreement took account of countries comes “contaminated” by a US person. Let’s

with banking secrecy to the extent that clients assume that Mr Abdullah has named his son

could be assigned to their individual categories by Omar, as well as some of his other adult sons, as a

the QIs themselves. Compliance with the agree- beneficiary of his trust. As American tax law has

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 3

W EGELIN & C O .

turned him into a US person, Omar renders the 3. The “green book” seeks the compulsory im-

trust liable to tax, and when Mr Abdullah dies, position of withholding tax at 30 percent on

this may mean that the entire inheritance be- US securities held by non-American compa-

comes liable to US estate tax, possibly at 45 per- nies. Any reclaiming would have to be done

cent, for Mr Abdullah was extremely wealthy. by the company itself, and involve disclosure

Perhaps, and then again, perhaps not. But that of its ownership structure. According to the

doesn’t matter – the QI should have known. “green book”, exceptions would be possible

The QI agreement of 2001 already exposed all the for pension funds, listed public companies

signatory banks worldwide to significant legal and the like.

risks vis-à-vis the American tax authorities. Even 4. Also stipulated is the introduction of with-

without actively canvassing for clients in the holding tax at 20 percent on all gross revenue

USA, as the UBS did with Alinghi and by other from transactions via a non-QI intermediary

means, the mere fact that someone can mutate, and in a country with no double taxation

almost unnoticed, from a non-US person into a agreement or inadequate exchange of infor-

US person is an unacceptable situation. For the mation.

result can be an entirely innocent misdeclaration. 5. The “green book” envisages compulsory dec-

laration of transactions over 10,000 US dol-

4. Green book; red content lars involving US persons via a non-QI inter-

mediary.

The Obama administration set out its intentions

with regard to various tax matters in May 2009, in 6. Notification to or recording by the IRS of the

a “green book” entitled “General Explanations of acquisition or foundation of an “offshore en-

the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2010 Revenue tity” on behalf of a US person is now also

Proposals”. In addition to the notion of forcing prescribed.

American businesses operating abroad to pay 7. Lastly, the involvement of an American audi-

more tax in America, the focus was on the exten- tor to monitor compliance with the QI agree-

sion of the “Estate Tax” and the tightening up of ment is envisaged. The report will have to be

the QI system. Essentially, the Obama admini- signed by this auditor.

stration is seeking to expand the application of This list of the intended amendments is not neces-

the QI system, and to plug all known and con- sarily complete, and may also contain minor inac-

ceivable loopholes. Seven significant changes curacies. What is clear, though, is that the USA is

deserve comment: attempting to exploit its almost unlimited position

1. The definition of a US security has been ex- of strength with regard to the international trans-

panded. In future, the QI system will also in- action systems (Swift, clearing systems, custodi-

clude equity swaps on US securities and on ans) and the fundamental attractiveness of its

securities lending. This should prevent US capital market to impose its ideas on the rest of

persons from entirely, and non-US persons the world. There is no question that signatories to

from partly, avoiding withholding tax by this new version of the QI agreement will need to

means of an OTC contract. According to the revise their business models for cross-border

“green book” the QI agreement is not (for wealth management, at least as far as US persons

the time being?) being expanded to cover are concerned. Both Swiss-style banking secrecy

non-US funds or derivatives that replicate US and the Austrian and Luxembourg versions, and

securities. indeed all Anglo-Saxon-style structures, whether

2. US persons are now required to report earn- managed from London, Dubai, Singapore or

ings and gross revenue from non-American Hong Kong, are called into question. As far as US

sources. This will extend the QI agreement to persons are concerned, the USA aims to abolish

cover the entire global financial universe, and cross-border business.

enforce disclosure by all US persons, in par- It might reasonably be observed that so long as

ticular those who, by not holding US securi- this really only affects its own citizens, the USA is

ties, had previously remained outside the QI absolutely entitled to do this. And to the extent

agreement. Should an intermediary wish to that it can exploit its position of power in the

remain outside the QI system, withholding world to enforce its intentions, we must – as we

tax at 30 percent is levied compulsorily, and have decided on as non-judgmental an analysis as

may only be reclaimed by the beneficiary, not possible – take note of this and adapt, or possibly

the intermediary. redimension our own business activities. The

concept of the “green book” is extraordinarily

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 4

W EGELIN & C O .

intelligent. The aim must have been “no way out” But that too is only part of the truth. A look at

– no loopholes. Sadly, however, the matter has who are the most important creditors of Amer-

not been properly thought through. The real ica’s highly indebted public finances reveals

problem lies not in the rigour of the law, but in something truly remarkable. It is the public au-

the lack of clarity about actual tax liability, and thorities themselves! A study by Sprott Asset

the resulting disproportionate effort required for Management, a Canadian asset management firm

monitoring and management. The enormously distinguished for its intelligent macroeconomic

expansive view of what constitutes a US person, analyses, showed that in 2008 over 4 trillion of the

and the potential, imperialist, expansion of inheri- total outstanding public debt of some 10 trillion,

tance tax liability to cover the whole world sub- or around 40 percent, was in the hands of so-

stantially increase the risk of investing in Amer- called “intragovernmental holdings”. These hold-

ica, and thus on the US capital market. This ap- ings include social welfare institutions, whose

plies for investors, but even more so for interme- assets, accumulated in order to be (halfway) able

diaries. While the old QI agreement put the to meet future liabilities, are invested in special

thumbscrews on them, the intended agreement Treasury debt instruments, known as “intragov-

will crush them in a vice. It is becoming clear that ernmental bonds”. In other words, the paying

it will be simply too dangerous to own US securi- recipient of, say, Medicare, the American health

ties, to hold them as a custodian for third parties, service, is an indirect source of finance for the

or to trade them as a bank. Treasury. Unusual, remarkable, or rather, alarm-

ing? Debtors are now simultaneously creditors.

5. The USA’s Achilles’ heel An unusual form of self-financing

4.3%1.2% 1.0% Ownership of US state debt

The sensibilities of their own capital market: this 4.6%

40.3% Intragovernmental holdings

is what the smart guys in the IRS have very 4.9%

Foreign

probably failed to take into account. Their one-

Other

sided regulatory proposals, focused on maximiz- 7.2%

Funds

ing the tax take, are based on the entirely unprob-

States

lematic and undisputed attractiveness of the USA 7.7%

Fed

as a place of investment for investors from all

Pension funds

over the world. We believe this assumption to be

Insurance companies

utterly wrong. Why?

Banks, savings banks

A glance at the USA’s debt situation suffices to

28.8%

show that apart from oil, there is really only one Note: Figures as of 31 December 2008

element of strategic importance that the USA will

Source: Financial Management Service (Bureau of the United

need in the coming years: capital. The (declared) States Department of the Treasury). Ownership of Federal

public debt – national, state and community – Securities and Federal Reserve Statistical Release.

amounted to some 70 percent of GDP in 2008. These “intragovernmental bonds” are certainly

With the absorption of further debt in the wake of not assets of genuine intrinsic value. Were we to

the financial crisis, by 2014 the level of explicit consolidate both balance sheets – that of the

debt is likely to be significantly above 100 percent Treasury and that of the institution concerned – it

of GDP. By then the interest will have doubled would produce a tautologous situation that would

from around 10 percent of total public revenue to only not result in the total loss of value of the

around 20 percent, on moderate assumptions. social welfare trust’s assets if the Treasury were in

This is generally well known. What is generally a position to avail itself of the capital market to

less well known is that in the USA too, as in so an ever greater extent. So let us look at this abso-

many ailing European states, this explicit perspec- lutely decisive cash flow situation.

tive reveals less than half the truth about what has According to the Canadian study quoted above,

been implicitly promised by the state in the way the American Treasury had to finance new debt

of future benefits. Correctly accounted – that is, of 705 billion dollars in 2008. This was needed to

as probable future payment flows discounted to cover the budget deficit of 455 billion dollars and

present values – the picture would look a good a special deficit for the war in Iraq and Afghani-

deal bleaker. There are studies, such as the one stan of 250 billion dollars. New debt in 2009 will

by the Frankfurt Institute in November 2008, that amount to somewhat more than 2,000 billion dol-

reckon with a total level of debt for the USA of lars, with some 200 billion going to the Middle

up to 600 percent (!) of GDP. Eastern war chest and 1,845 billion to the “regu-

lar” budget deficit. This debt must be bought,

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 5

W EGELIN & C O .

financed, by someone. So how are the individual And nota bene: we have not yet discussed the

categories of creditors behaving? Number 2 in the quality of the growth. Over the last 15 years it

ranking of creditor groups are the “Foreign and has, as we know, increasingly come mainly from

International Holders”; that is, the total of all consumption and state expenditure; investment in

foreign creditors, including central banks, sover- the USA is extraordinarily weak. Far too little

eign wealth funds, private investors and so on. In potential for the future is being created.

2008 they bought some 560 billion dollars’ worth;

in this year so far, just 460 billion. In March and

April they were net sellers of government securi- 6. Rats leaving the sinking ship

ties. Other categories, such as pension funds, It can hardly be a coincidence that two of the

states, communities and investment funds, also most prominent and most successful American

seem to be tending to unload government paper investors, Warren Buffett and Bill Gross, chose

this year. This means that the usual sources of precisely the same moment to speak out very

finance for the American state are drying up. The clearly against their own domestic currency and

last hope of salvation comes from the Fed, which, against investments in US government securities.

with its quantitative easing programme for print- In an op-ed article in the New York Times on 18

ing money, is currently having to buy up to half August 2009, Buffett described the Treasury’s

the newly issued debt, month after month. current financing problems, with similar assump-

This will be OK as long as it’s OK. A Ponzi tions and observations to those of Sprott Asset

scheme, for that is undoubtedly what we are talk- Management, and lamented the necessity for the

ing about, goes on working as long as its growing Fed, as the lender of last resort, to intervene so

overindebtedness does not arouse any doubt extensively, by means of the printing press. In his

among the public as to the scheme’s continuing own words: “The United States economy is now

performance, and the flow of funds to the scheme out of the emergency room and appears to be on

is not significantly disturbed by other influences. a slow path to recovery. But enormous dosages of

As we know, Madoff’s scheme only collapsed monetary medicine continue to be administered

when individual creditors had liquidity problems and, before long, we will need to deal with their

and were obliged to withdraw funds. side effects. For now, most of those effects are

invisible and could indeed remain latent for a

Hopelessly in debt long time. Still, their threat may be as ominous as

Debt as % of US GDP

400%

that posed by the financial crisis itself.” Buffett

Government fears high inflation, and consequently advises

350% States

Financial sector against the purchase of long-term Treasury bills.

300% Businesses

Households Bill Gross of Pacific Investment Management Co.

250%

(Pimco), which manages the biggest bond fund in

200%

the world, advises investors to sell dollar invest-

150% ments “before the central banks and sovereign

100% wealth funds do”. It’s time to take advantage of

50% the recovery of the US dollar to get one’s cur-

0%

rency diversification in order. The somewhat

1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 strident commodities specialist Jim Rogers takes

Source: Federal Reserve. Flow of Funds Account. the same line, and also announces his new favour-

ite currency – the Chinese yuan. He is seconded,

We now believe that the combination of the US with a good deal more substance, by Hossein

tax authorities’ anti-capital-market plans with the Askari, a professor at George Washington Uni-

Treasury’s specific financing problems could re- versity. In a very readable article in the Asia

sult in such a situation. For the growth of debt Times on 6 August 2009, he also advocated a

alone would give sufficient cause for doubt as to global currency, which “would not be allowed to

performance. The figure above shows the long- be used to finance state debt or stimulation meas-

term development of overall US debt – that is, ures”.

public, household and business debt – compared

to economic performance. It is obvious that, for Without in any way wishing to overdramatize

about 30 years now, additional growth has only matters, we do believe that such signals should be

come at the cost of ever-higher debt. Today, taken seriously. In exactly the same way as it is

every dollar of growth comes with about 4 dollars inadvisable to ignore rats leaving a sinking ship.

of debt. For they often know the crucial aspects of the

ship better than the captain and the officers. The

least worst outcome that we expect for the USA,

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 6

W EGELIN & C O .

and for the Treasury in particular, is significantly own efforts. Those who produced too cheaply

higher financing costs for debt incurred in the were taken to court, big businesses were given

future. We calculate the medium-term contribu- blatantly preferential treatment, and property

tion by the American tax authorities to this added rights increasingly threatened. Without the exter-

expense, as a result of the “keep foreigners out” nal event of the Second World War, Roosevelt

strategy described above, at around 50 basis would have been numbered among the most un-

points. And this is precisely the Obama admini- successful American presidents of all time.

stration’s miscalculation. Their aggressive attitude The financial crisis has given momentum to anti-

to tax exiles will generate extra funds, perhaps capitalist, and thus anti-market forces in the USA

running into billions, but the price they pay will (and elsewhere). That promises little good for this

be exorbitant. An increase in the credit spread of part of the world, but it makes it somewhat easier

50 basis points on total public debt of over for investors to take their leave. Our bank is in

10 trillion US dollars represents increased costs of the process of recommending our clients to exit

50 billion per annum. The sums don’t work: to from all direct investments in US securities. This,

make up for this would require additional taxable on the grounds of the threat of inheritance tax

funds of some 2 trillion US dollars. coupled with the uncertainty as to whether one

might not, one way or another, be turned into a

7. Unattractive anyway US person.

Furthermore, the stupendous increase in Ameri- We do not deny that by doing this, we hope to

can debt is by no means a problem only for the significantly reduce the risk carried by our bank

Treasury, but affects the economy as a whole. The as an intermediary. Should we maintain QI status

state’s ravenous appetite for debt is preventing under the new, more rigorous conditions, we will

private borrowers from getting access to the avail- have so far reduced our holding of US securities

able finance. This is known as the “crowding-out that we shall effectively be spared most dealings

effect”. The aim of the Fed’s quantitative easing with these cumbersome foreign authorities. Inves-

policy is to counter this effect. At the same time, tors who need US exposure on diversification

distressed banks, and whole industry sectors, like grounds, can obtain it via non-US securities – the

car manufacturers, are being subsidized with “green book” explicitly excludes derivatives and

enormous sums, which ultimately must result in non-US funds from withholding tax. And as we

further distortions, and crass disadvantages for assume that we are not the only ones who will be

the unsubsidized part of the economy. pursuing a policy of exit from the American capi-

tal market, we expect that the range of non-US

This generally anti-entrepreneurial policy of dis- securities with American exposure will expand

couraging investment is further reinforced by significantly. This may be good news for Mr Ab-

wholly disproportionate efforts to intensify the dullah of Dubai.

regulation of small businesses. From the Wall

Street Journal, we learn that legislation already But then again, it may not. If this picture of a

exists in Washington that would impose reporting tautologous construct round the US Treasury is

obligations on small venture capital enterprises – correct, then we must at the very least be ex-

exactly those that have powered the rise of Silicon tremely cautious about nominal values. For

Valley – whose administrative burden would be Treasury bonds and bills would then be seriously

simply unsupportable. And this just because of overvalued, as would the US dollar itself, which

the concern that hedge funds, which, rightly or would naturally argue against all other US bonds.

wrongly, are felt to require greater control, might In our view, not even an engagement in US stocks

be able to operate in the guise of such venture is really worthwhile. Despite depreciation in the

capital companies. If Washington gets its way, this financial crisis, according to our calculations they

will mean the end for many small businesses with are still valued at around 12 percent above the

10 to 20 employees. long-term fair price, whereas European stocks are

undervalued by almost 17 percent. And these

In this economic crisis, the Obama administration calculations do not include the impact of any fu-

is making exactly the same mistake as its great ture increases in taxation or interest rates.

hero, Franklin D. Roosevelt, made in what is

quite wrongly regarded as the exemplary “New We live at a time of shifting power and influence

Deal”. Driven by Keynesian ideology and a belief in the world. Asia is on the rise, and Brazil too,

in the possibility of an upturn caused by appro- probably. Australia will catch on to their coattails,

priate state intervention, in the course of the and Europe may once more be able to position

1930s, Roosevelt deprived businesses of any hope itself within these countries’ recoveries. The USA

of being able to make money again through their will remain the unquestioned military power and

Investment Commentary No. 265 Page 7

W EGELIN & C O .

also an enormous repository of debt and other why we are well advised to take a general farewell

problems. Because they are painful, and there of America. This will be painful, for the USA was

is always an inclination to shift the blame for once the most vital market economy in the world.

them onto third parties, redimensioning processes But for now, it’s time to say goodbye.

always harbour the potential for aggression. Switz-

erland is currently experiencing just this. But it

won’t end there. Potential aggression and eco-

nomic progress are mutually exclusive. Which is KH, 24.08.2009

WEGELIN & CO. PRIVATE BANKERS PARTNERS BRUDERER, HUMMLER, TOLLE & CO.

CH-9004

Investment St. Gallen Bohl 17

Commentary No.Telephone

265 +41 71 242 50 00 Fax +41 71 242 50 50 wegelin@wegelin.ch www.wegelin.ch Page 8

ST. GALLEN BASEL BERNE CHUR GENEVA LAUSANNE LOCARNO LUGANO SCHAFFHAUSEN ZURICH

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 20sep16 Anna Von Reitz The Truth Has Come Out Finally and ConclusivelyDokument6 Seiten20sep16 Anna Von Reitz The Truth Has Come Out Finally and ConclusivelyNadah8100% (2)

- CautionaboutbondsDokument3 SeitenCautionaboutbondsWayne Lund100% (3)

- Annavonreitz-Pay To USDokument3 SeitenAnnavonreitz-Pay To USaplawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handouts & Pickpockets - Our Government Gone Berserk 1996Dokument197 SeitenHandouts & Pickpockets - Our Government Gone Berserk 1996Anonymous nYwWYS3ntV100% (2)

- Instructor Manual For Financial Managerial Accounting 16th Sixteenth Edition by Jan R Williams Sue F Haka Mark S Bettner Joseph V CarcelloDokument14 SeitenInstructor Manual For Financial Managerial Accounting 16th Sixteenth Edition by Jan R Williams Sue F Haka Mark S Bettner Joseph V CarcelloLindaCruzykeaz100% (80)

- The Dispatch of Merchants - Copy P.7Dokument72 SeitenThe Dispatch of Merchants - Copy P.7Luc LeblancNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom Without BordersDokument192 SeitenFreedom Without BordersIrfan Sylvanto100% (1)

- Panama PapersDokument22 SeitenPanama PapersBeLa JuniartNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminals On Our ShoresDokument5 SeitenCriminals On Our Shorestrinadadwarlock666100% (1)

- Great Red Dragon Short VersionDokument88 SeitenGreat Red Dragon Short VersionChristTriumphetNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Myth of Manipulation The Economics of Minimum WageDokument65 SeitenThe Myth of Manipulation The Economics of Minimum WageAndrew Joliet100% (1)

- Management Information System of Standard Charterd Bank PVT LTDDokument17 SeitenManagement Information System of Standard Charterd Bank PVT LTDUnscrewing_buks92% (13)

- Account statement from 4 Apr 2023 to 26 Apr 2023Dokument7 SeitenAccount statement from 4 Apr 2023 to 26 Apr 2023BIKRAM KUMAR BEHERANoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Distressed AssetsDokument37 SeitenManaging Distressed Assetsodumgroup100% (2)

- Offshore: Tax Havens and the Rule of Global CrimeVon EverandOffshore: Tax Havens and the Rule of Global CrimeBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (4)

- NON COMPETE CLAUSE PLJ Volume 83 Number 2 - 04 - Charito R. Villena PDFDokument28 SeitenNON COMPETE CLAUSE PLJ Volume 83 Number 2 - 04 - Charito R. Villena PDFHeart Lero100% (1)

- Optimize Cash Flow With Electronic PaymentsDokument22 SeitenOptimize Cash Flow With Electronic Paymentshendraxyzxyz100% (1)

- International Pack of Climate CrooksDokument10 SeitenInternational Pack of Climate CrooksPatschef2100% (1)

- February 17, 1913Dokument6 SeitenFebruary 17, 1913TheNationMagazineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accounting for Derivatives and Hedging ActivitiesDokument22 SeitenAccounting for Derivatives and Hedging Activitiesswinki3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Doing What We Can For Haiti, Cato Policy AnalysisDokument8 SeitenDoing What We Can For Haiti, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEC 2º Semestre - Abraham Lincoln The Emancipation Proclamation 1863Dokument5 SeitenPEC 2º Semestre - Abraham Lincoln The Emancipation Proclamation 1863Olga Iglesias EspañaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palmer Limited Case Study AnalysisDokument9 SeitenPalmer Limited Case Study AnalysisPrashil Raj MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lugano ReportDokument4 SeitenLugano Reportprem101Noch keine Bewertungen

- History of Crime and Criminal Justice in America EditedDokument7 SeitenHistory of Crime and Criminal Justice in America EditedcarolineNoch keine Bewertungen

- 622 - WORD The Logos and The RhemaDokument18 Seiten622 - WORD The Logos and The RhemaAgada Peter100% (1)

- Speech by DavynDokument4 SeitenSpeech by DavynNicole Lebrasseur100% (1)

- 4LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Reply Sentencing MemoDokument26 Seiten4LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Reply Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNoch keine Bewertungen

- German Federalism - Still ADokument7 SeitenGerman Federalism - Still AAliSaumerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laws Lifting Sovereign Immunity in Selected CountriesDokument19 SeitenLaws Lifting Sovereign Immunity in Selected CountriesBeverly TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits of SecuritisationDokument3 SeitenBenefits of SecuritisationRohit Kumar100% (2)

- 2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoDokument403 Seiten2LOLES Gregory Govt Supp Sentencing MemoHelen BennettNoch keine Bewertungen

- FREE and FAIR-How Australias Low Tax Egalitatianism Confounds The World-Alexander-2010Dokument13 SeitenFREE and FAIR-How Australias Low Tax Egalitatianism Confounds The World-Alexander-2010Darren WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- De 77 2023 02 23 (Fuller) 1st Amd ComplaintDokument124 SeitenDe 77 2023 02 23 (Fuller) 1st Amd ComplaintChris GothnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 OmmissionDokument3 Seiten3 OmmissionMahdi Bin Mamun100% (1)

- British Virgin IslandsDokument12 SeitenBritish Virgin IslandsRamona SerdeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- BOL ACLUPR CCR Submission To UN HRC On Self-Determination 9.12.2023Dokument105 SeitenBOL ACLUPR CCR Submission To UN HRC On Self-Determination 9.12.2023acluprNoch keine Bewertungen

- February 15, 1898Dokument4 SeitenFebruary 15, 1898TheNationMagazineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why The US Embargo Against Cuba FailedDokument11 SeitenWhy The US Embargo Against Cuba FailedRuohan Hannah ZhangNoch keine Bewertungen

- ORR Staff MemoDokument56 SeitenORR Staff MemoblankamncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Owen, Henry. El Banco Mundial ¿Son Suficientes 50 Años. 12 Páginas, Inglés.Dokument8 SeitenOwen, Henry. El Banco Mundial ¿Son Suficientes 50 Años. 12 Páginas, Inglés.Karo GutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- O T Public - PleaDokument2 SeitenO T Public - PleaoldeproNoch keine Bewertungen

- Van Camp V BradfordDokument2 SeitenVan Camp V Bradfordjohnconnorpatriot100% (1)

- Mock Trial Case Andrew JacksonDokument3 SeitenMock Trial Case Andrew JacksonForis KuangNoch keine Bewertungen

- U.S. Attorney Request For RehearingDokument45 SeitenU.S. Attorney Request For RehearingXerxes WilsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lawsuit Against DeWine, Ohio Over Coronavirus RestrictionsDokument56 SeitenLawsuit Against DeWine, Ohio Over Coronavirus RestrictionsJo InglesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Analysis and Evaluation Enron Corporation Scandal Prepared For: Marcos A. KerbelDokument7 SeitenEthical Analysis and Evaluation Enron Corporation Scandal Prepared For: Marcos A. Kerbellcorrente12100% (1)

- The Pseudoscience of EconomicsDokument30 SeitenThe Pseudoscience of EconomicsPeter LapsanskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 Topic 3 Tax Havens and GlobalizationDokument12 SeitenModule 3 Topic 3 Tax Havens and GlobalizationRosalyn BacolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time To Shake Down The Swiss BanksDokument4 SeitenTime To Shake Down The Swiss Banksrvaidya2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Layoffs Lists 2000 To 2005 Volume IIDokument310 SeitenCorporate Layoffs Lists 2000 To 2005 Volume IIJaggy GirishNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityDokument8 SeitenWall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityTA WebsterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birkenfeld 2010Dokument3 SeitenBirkenfeld 2010Kang Ian2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wall Street Is To BlameDokument3 SeitenWall Street Is To BlameUruk SumerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Werner - Revisiting The Necessity ConceptDokument4 SeitenWerner - Revisiting The Necessity ConceptMieras HandicraftsNoch keine Bewertungen

- America As Tax HavenDokument4 SeitenAmerica As Tax Havensmarak_kgpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Threats To Financial Privacy and Tax Competition, Cato Policy Analysis No. 491Dokument14 SeitenThreats To Financial Privacy and Tax Competition, Cato Policy Analysis No. 491Cato InstituteNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Massive Bubble Is Just Weeks Away From Bursting. andDokument24 SeitenThis Massive Bubble Is Just Weeks Away From Bursting. andAdiy666Noch keine Bewertungen

- Here Is A Method That Is Helping International Tax AccountantdqqriDokument4 SeitenHere Is A Method That Is Helping International Tax Accountantdqqributterfoot87Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dropping The BombDokument6 SeitenDropping The BombDevi PurnamasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blog On Bribery: ReportsDokument4 SeitenBlog On Bribery: ReportsHarry BlutsteinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Revolution Will Be DigitizedDokument4 SeitenThe Revolution Will Be DigitizedToronto Star100% (1)

- Matt Taibbi The Big TakeoverDokument21 SeitenMatt Taibbi The Big Takeovergonzomarx100% (1)

- Why Switzerland Is Ending Its Precious - Banking Secrecy Laws?Dokument2 SeitenWhy Switzerland Is Ending Its Precious - Banking Secrecy Laws?Ashwin RajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gekko Echo - A Closer Look at The "Decade of Greed"Dokument12 SeitenGekko Echo - A Closer Look at The "Decade of Greed"Jeffery ScottNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registration Leads to ConfiscationDokument8 SeitenRegistration Leads to ConfiscationAJ SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - September 30, 2012Dokument7 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - September 30, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - September 30, 2012Dokument7 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - September 30, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - August 2, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - August 2, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - July 6, 2012Dokument7 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - July 6, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - August 29, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - August 29, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMD Monsoon Onset 2012Dokument4 SeitenIMD Monsoon Onset 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - August 22, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - August 22, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - September 14, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - September 14, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Authority of State Registration DescriptionDokument27 SeitenGeneral Authority of State Registration DescriptionParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - August 8, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - August 8, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - July 19, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - July 19, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- All India Weather Bulletin - July 25, 2012Dokument6 SeitenAll India Weather Bulletin - July 25, 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- CERN BE Newsletter May 2012Dokument9 SeitenCERN BE Newsletter May 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Federation of Independent Business v. SebeliusDokument193 SeitenNational Federation of Independent Business v. SebeliusCasey SeilerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syrian Draft Constitution 2012Dokument23 SeitenSyrian Draft Constitution 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bahrain Land OwnershipDokument45 SeitenBahrain Land OwnershipParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Report of The Head of The League of Arab States Observer Mission To Syria For The Period From 24 December 2011 To 18 January 2012Dokument30 SeitenReport of The Head of The League of Arab States Observer Mission To Syria For The Period From 24 December 2011 To 18 January 2012aynoneemouseNoch keine Bewertungen

- LHC Schedule 2012Dokument1 SeiteLHC Schedule 2012ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- OTC Derivatives Market Activity in The First Half of 2011Dokument32 SeitenOTC Derivatives Market Activity in The First Half of 2011ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measurement of The Neutrino Velocity With The OPERA Detector in The CNGS BeamDokument32 SeitenMeasurement of The Neutrino Velocity With The OPERA Detector in The CNGS BeamParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statement of Admiral Mullen Before The Senate Armed Services CommitteeDokument8 SeitenStatement of Admiral Mullen Before The Senate Armed Services CommitteeParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- End of Season Report Monsoon 2011Dokument14 SeitenEnd of Season Report Monsoon 2011ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Losses/damages Due To Rain in Sindh - 2011 - 9/15Dokument1 SeiteSummary of Losses/damages Due To Rain in Sindh - 2011 - 9/15ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1109Dokument24 Seiten1109الغزيزال الحسن EL GHZIZAL HassaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pager - M 6.9 - India-Nepal Border RegionDokument1 SeitePager - M 6.9 - India-Nepal Border RegionParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary - July 2011Dokument16 SeitenJob Openings and Labor Turnover Summary - July 2011ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- OCC's Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities Report Q2 2011Dokument36 SeitenOCC's Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities Report Q2 2011ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- UARSDokument11 SeitenUARSThe Huntsville TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- SNB: Extension of Dollar-LiquidityDokument1 SeiteSNB: Extension of Dollar-LiquidityParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Status of Countermeasures Fukushima Daiichi 11.09.2011Dokument2 SeitenStatus of Countermeasures Fukushima Daiichi 11.09.2011ParvanehNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Guide To Homeownership by Myra - 020631Dokument52 SeitenA Guide To Homeownership by Myra - 020631reizei.eihiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ific BankDokument95 SeitenIfic BankAl AminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Audit of Bank of BarodaDokument27 SeitenAudit of Bank of BarodaKiara MpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Unit 3 Notes: Sources, Costs & Break-EvenDokument45 SeitenBusiness Unit 3 Notes: Sources, Costs & Break-Evenamir dargahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- KGSGDokument7 SeitenKGSGAnonymous V9E1ZJtwoENoch keine Bewertungen

- Monetary Policy of Bangladesh: An AssignmentDokument12 SeitenMonetary Policy of Bangladesh: An Assignments_rrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical Issues in Financial Management PDFDokument2 SeitenEthical Issues in Financial Management PDFMalik25% (4)

- Provisions Applicable Only To Pledge DigestsDokument9 SeitenProvisions Applicable Only To Pledge DigestsMikkaEllaAnclaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ds Team D Group ProjectDokument57 SeitenDs Team D Group ProjectRenuka Badhoria (HRM 21-23)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction of Internet Banking: Keywords: Online Banking, Financial Institution, ATM, Mobile Banking EtcDokument75 SeitenIntroduction of Internet Banking: Keywords: Online Banking, Financial Institution, ATM, Mobile Banking Etcakshay mouryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maphar Constructions Private LimitedDokument2 SeitenMaphar Constructions Private LimitedSWARUPANoch keine Bewertungen

- SwiftDokument61 SeitenSwiftdebarghya.official2021Noch keine Bewertungen

- $6,975.36 Total Assets: Balances and HoldingsDokument2 Seiten$6,975.36 Total Assets: Balances and Holdingsnnenna26Noch keine Bewertungen

- Online BankingDokument40 SeitenOnline BankingIsmail HossainNoch keine Bewertungen

- TITLE PAYMENTDokument10 SeitenTITLE PAYMENTJeff FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mail From ANisDokument3 SeitenMail From ANissantolaseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community rewarding gateway for Blockchain and Leadership educationDokument43 SeitenCommunity rewarding gateway for Blockchain and Leadership educationClaudiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Navi Consumer Loans Case SubmissionDokument4 SeitenNavi Consumer Loans Case SubmissionABHIRAM MOLUGUNoch keine Bewertungen

- NAB CEO Press Conference Transcript PDFDokument4 SeitenNAB CEO Press Conference Transcript PDFmrfutschNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assistant Protocol OfficerDokument3 SeitenAssistant Protocol OfficerMEHRU NADEEMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Small Scale IndustriesDokument28 SeitenSmall Scale IndustriesMohit Gupta25% (4)

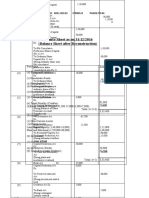

- Balance Sheet As On 31/12/2016 (Balance Sheet After Reconstruction)Dokument8 SeitenBalance Sheet As On 31/12/2016 (Balance Sheet After Reconstruction)GauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking Sector ReformsDokument15 SeitenBanking Sector ReformsKIRANMAI CHENNURUNoch keine Bewertungen