Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Isaiah 61 2

Hochgeladen von

TheologienCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Isaiah 61 2

Hochgeladen von

TheologienCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Reset Button Jesus via Isaiah is referencing Leviticus 25s description of the Year of Jubilee.

This is commanded to take place every fiftieth year. During this amazing year, justice and equanimity is supposed to reign. All debts are forgiven; the captives go free; the prisoners are released; and nobody does any work. The Year of Jubilee was designed to be a sort of social reset button. It is a control against the amassing of wealth and poweran acknowledgement of and correction to our tendencies toward corruption. When too much is controlled by too few, it usually turns out very bad for the many. The scope of the promises of Isa 61 is markedly broadened, however, from that of Isa 40. The message is no longer limited to the exiles. The proclamation is addressed both to the people of Israel and through them to the nations. The transformations announced by Isa 61 mark a universal reversal and a manifestation of justice and comfort to all the world. The Good News is directed to the afflicted, to the poor (61:1b). All suffering is reversed; the brokenhearted are bound up; the captives are liberated (61:1c). Time itself is redefined. The year of Jubilee is proclaimed, and the theophanic day of judgment, so life-threatening in Isa 64, now brings comfort to those who mourn (61:2). Even the songs of lament, like the one which ushered in Advent, are now to be clothed in the mantle of praise. The people of Israel shall receive a new name, Oaks of Righteousness, the planting of the LORD. Here, for the first time, the implication is that the Davidic tree has been cut down. But it grew from mere Jesse in the first place, so there is no reason why it should not do so again. The idea of going behind David to his roots in Jesse to fulfill the promise even points to the possibility of a critique of David himself, whose weaknesses are exposed in Samuel-Kings. It turns out that this development in imagery is a transitional one. While the implications of this promise could have been worked out in terms of the image of the fruitfulness of a tree, verses 23a describe the promise according to a different framework, centering on the image of spirit. When Yahwehs spirit rests on the branch, it bears fruit in the form of capacities to which human beings (including monarchs) generally only pretend. That was true of Assyrias wisdom and understanding (10:13). It was true earlier of the nations counsel (8:10) and of Judahs power (see 3:25, the word lies behind the reference to warriors there). The words counsel and power also evoke the attributes of the Counselor and Mighty God of 9:6. It was true of Judahs lack of knowledge (5:13) and its misdirected fear (7:4; 8:1213; 10:24). All these attributes have been referred to as belonging to God and/or as misclaimed by human beings. 11:10 11:1016 Another reference to the Root of Jesse facilitates a further transition to a different agenda, namely the restoring of the remnant of Yahwehs people to its land. As Yahweh raised a banner to summon the nations to punish (5:26), so now the Davidic shoot draws the remnant back, standing as a banner to summon the nations to help their victims go home. They will rally to him or seek him. The promise is ironic, for seeking was Judahs problem on the way to its being reduced to a remnant (8:19; 9:13). They will be drawn to the branch as they will be drawn to Zion (2:24), and he will have glory for the nations to recognize (cf. 4:2). Kings are anointed, not prophets (it is not an office in the Heb. Scriptures) 61:1 61:19 The first of the five responses, then, is preaching. Once again the prophet takes up forms of speech as well as actual words from chapters 4055. The first-person testimony corresponds to 48:16, 49:16, and 50:49, where it is also the Lord Yahweh who speaks (48:16; 50:4,5,7,9). The claim that the Lord

Yahwehs spirit is on me recalls the earlier servant passage 42:1 (and as there, capitalizing Spirit risks giving a misleading Like the Poet in 49:16 and 50:49, this prophet reckons to be the very embodiment of that servant vision in 42:19. This gives us a clue to the sort of ministry the prophet exercises. This prophet also has a distinctive way of understanding that commission: the LORD has anointed me. In Christian thinking, the two expressions in verse la have become one and we regularly think of anointing with the Holy Spirit, but these two were not normally associated with each other in the OT. Anointing suggests commissioning, consecrating, and authorizing. The spirit suggests endowing with supernatural power. Anointing is a striking metaphor here. In Israel and elsewhere, people daubed priests and kings with olive oil as part of their consecration to holy office, and such daubing became a figure for Yahwehs commissioning (e.g., 1 Sam. 10:1; 2 Sam. 12:7). Prophets were not anointed (being a prophet was not an office), except in I Kings 19:16. Only in connection with David do the two ideas of anointing and Yahwehs spirit come closely together (see 1 Sam. 16; 2 Sam. 23). In effect, then, this prophet claims to be a David-like figure for the community, anointed (metaphorically) like David and endowed like David. Whether we think of the prophet as claiming Davids mantle, the task it implies is indeed the kings task, We have noted how Psalm 72 illumines chapter 60, and it now illuminates chapter 61 as well (see also 11:19). Psalm 72 assumes that the kings calling involves a particular commitment to the afflicted and the needy (vv. 2, 4, 12; see on 32:18). Here the anointed Preacher takes up that commitment. The kings task was to take action in making decisions that would favor the afflicted and needy. The Preachers task is to make an announcement to them. Once again preach good news takes up from chapters 4055 and suggests that the prophet also reckons to be the fulfillment of the commission and vision of heralds bringing good news to Jerusalem (see 40:9; 41:27; 52:7). Further, to judge from the verses that follow, the word poor designates the community as a whole. While chapters 5659 presupposed divisions within the community and the leadership doing well at the expense of ordinary people, chapters 6062 look on the community as a whole as oppressed and sorrowful, in the manner of chapters 4055. So despite their reconstitution in Jerusalem, the people remain poor (see on 29:19), brokenhearted, demoralized, crushed in mind and spirit (cf. Ps. 34:18; 51:17), captives in their own land (cf. Ps. 106:46), prisoners (cf. 49:9), people who grieve the continuing suffering of their city (cf. 57:1719) and who are metaphorically smeared with the ashes of mourning (y. 3; cf. 58:5; 60:20; Lam. 3:16). They still live in a devastated city (y. 4), and are still shamed by the well-deserved humiliation that had come from Yahweh (v. 7). The Preacher is sent to announce a transformation of all that and thus to bind up the people who are crushed in mind. That is to come about by bringing good news and announcing the coming of freedom (the word is otherwise used only of the freeing of slaves at the sabbath or jubilee year) and release for these people who

are still subject to foreign control(v. 1). This is the moment of Yahwehs favor on one hand and vengeance on the other. The parallelism signals the fact that these are two sides of one idea. In taking the side of the victims and acting on their behalf, Yahweh will put down the oppressors and punish them. Like 40:35, verses 13 aroused particular interest among the Qumran community (who applied them to Melchizedek, understood as a member of the heavenly cabinet) as well as among other Jews (who usually assumed they were the words of the prophet himself). There would thus seem to be some arrogance about Jesus applying the words to himself (Luke 4:1429). There would also be good news in Jesus declaration that their moment had come. Jesus commits himself to proclaiming the liberation of the Jewish people from foreign oppressors, though he combines this commitment with a commitment to outsiders (vv. 2427) that corresponds to that in passages such as Isaiah 56:18. His audience is less pleased with this. In Luke 4 he stops short of the phrase about the day of vengeance, but takes up such talk of days of vengeance in 21:22 (NIV time of punishment). These must come in fulfillment of all that has been written. Jesus says that even the promise of Gods day of vengeance must be fulfilled. Paradoxically, Jesus days of vengeance are ones exacted on his own people. More radically than was the case in Luke 4, in Luke 21 Jesus is reversing the significance of the promise. Amos did the same thing when he turned the Day of Yahweh from good news to bad news (see Amos 5:1820). But when asked when Israel would get its freedom, Jesus answered not Never, or That is the wrong question, but It is not for you to know(Acts 1:6-7). 61:10 61:1011 / The prophets second response to the promises of chapter 60 is to praise. In line with the intended relationship between prophet and people, the Preacher thus models a response to which the whole people is called. They are to offer this response before the event actually happens, in accordance with the summons that chapters 4055 often made to their audience. 10 I exult for joy in Yahweh, my soul rejoices in my God, for he has clothed me in garments of salvation, he has wrapped me in a cloak of saving justice, like a bridegroom wearing his garland, like a bride adorned in her jewels. 11 For as the earth sends up its shoots and a garden makes seeds sprout, so Lord Yahweh makes saving justice and praise spring up in the sight of all nations. 62:1 62:15 / The prophets third response is a commitment to prayer. In other contexts, refusing to keep silence out of a concern for Jerusalem-Zions righteousness might suggest speaking out to her of her wrongdoing. Here it denotes speaking out to Yahweh about the fulfillment of her destiny, about her tsedaqah, her vindication, which means her salvation. We may pray for the sake of Gods name, but we also pray for Zion/Jerusalems sake, for the sake of the people on whose behalf we long to motivate God to act. 62:6 62:69 / The prophets fourth response is to be a watchman. The next stanza, v 6f, runs parallel with vv. 1-3: Jerusalem ... never be silent ... until. The prophets inspiration in v. I is now found to be a directly appointed divine task. He is merely one of the watchmen on Zions walls who look forward to the great Dawn. God himself says: watch for the fulfillment of the promise! Without cease, day and night, proclaim hope! And while God says this to Jerusalem, the prophet interrupts Him, as it were, to call to these watchmen. They

themselves must never rest. They must give God no rest. For He cannot accept that his promise has not yet been realized. And so He must be badgered, with shameless boldness, Luke 11:5ff; 18:1ff. We are the watchmen, like sentries on the city wall, keeping our eyes peeled for what God is doing in the world today. We encourage one another about these momentous events. We also speak to God. In fact, with language I wouldnt have dared to use, our prayers are to give God no rest until a revived church astonishes the world. Jonathan Edwards wrote a famous appeal to the Christians of his day to unite in prayer for revival. At the end of his appeal he wrote this: It is very apparent from the Word of God that he often tries the faith and patience of his people, when they are crying to him for some great and important mercy, by withholding the mercy sought for a season; and not only so, but at first he may cause an increase of dark appearances. And yet he, without fail, at last prospers those who continue urgently in prayer with all perseverance and will not let him go except he blesses. (NB Jacob image) There is another important addition already sounded in v. 1, which is then greatly developed in v. 6. In v.1 the prophet emerges in great agitation to announce that he will neither rest nor keep silent until Gods promises of Zions vindication arid salvation have become a reality. Then in v. 6 the prophet expands his task by adding helpers to aid him in his avowed mission. Upon the walls of Jerusalem he has appointed watchmen who will also not be silent day or night. Their task, like the prophets, is continually to remind God of Israels plight. and to call for divine intervention. Indeed, they will give God no peace until he has established Jerusalem according to his promises. 62:10 62:1012 / The prophets fifth response is to commission workers. Again, out of context one might take these verses as Yahwehs words. But the fact that the prophets voice has been so prominent, as well as the fact that these verses refer to Yahweh in the third person, suggests that the prophet speaks for one last timeon this occasion not in testimony but in command. The style and word choice of verses 1012 recall chapters 4055 in an especially systematic way. The repeated commands recall the very beginning of those chapters and the repetitions in 51:952:12. The command to pass through the gates recalls 48:20 and 52:11, though typically the meaning of the words has changed. The words that follow suggest that here the command is part of the commission to unnamed construction workers such as were commissioned earlier in 40:35. The purpose of the road has also changed. That was a road for Yahweh (though Yahweh would bring the people along). This is a road explicitly for the people. Further, in verse 10 they are brought along not by Yahweh but by the nations, for this summons takes 49:22 into account. Admittedly verses 1112 return (among other passages) to 40:1011 and depict Yahweh as the peoples Savior bringing them home to Zion. In chapters 4048 and 4955 the focus was first on the freeing of the deportees and then on the city s being able to receive them: verses 1112 sum up both aspects of Yahwehs act of restoration.

Watchman The prophet is a watchman for the house of Israel (Ezek 3:17; Acts 20:28). The literal role of a watchman warning the city of impending attack is first presented as the background for the prophets metaphorical role to warn Israel of divine punishment. His calling includes both watching out for the dangers of sin (Hos 9:8) and watching for signs of divine deliverance (Mic 7:7). Like God himself, those who watch over Israel are to give themselves no rest (Is 62:6), suggesting that they are in perpetual prayer for Gods people. Watching takes on eschatological overtones in the NT. Like the homeowner who watches for the thief, or the servant who watches for the master, or the virgins who watch for the bridegroom, the followers of Christ must be ready perpetually for the unpredictable return of the Son of Man (Mt 24:4225:13). The diligent urgency of life in Christ in the present age is thus captured in the single command Jesus gives his disciples: Watch! (Mk 13:3237; cf. Mk 14:3242). Hab 2 1 I will stand at my post, and station myself on the rampart. And I will keep watch to see what he will say to me, and what he will answer concerning my complaint. Cant 3 3 The watchmen came upon me, as they made their rounds of the city. 'Have you seen my true love? ' I asked them.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Easter 2016 SermonDokument5 SeitenEaster 2016 SermonTheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Deity of Christ-2Dokument3 SeitenThe Deity of Christ-2TheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moving From Solitude To Community To MinistryDokument9 SeitenMoving From Solitude To Community To MinistryTheologien100% (1)

- BEYOND JUSTIFICATION: AN ORTHODOX PERSPECTIVE Valerie A. KarrasDokument15 SeitenBEYOND JUSTIFICATION: AN ORTHODOX PERSPECTIVE Valerie A. KarrasTheologien100% (1)

- Roland Allen and The Spontaneous Expansion of The ChurchDokument2 SeitenRoland Allen and The Spontaneous Expansion of The ChurchTheologien100% (1)

- Application For Isa-61 SermonDokument2 SeitenApplication For Isa-61 SermonTheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Milk For BabesDokument27 SeitenMilk For BabesTheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Principles For GivingDokument12 Seiten10 Principles For GivingTheologienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar Lectionary For Christian Year 2017Dokument9 SeitenMar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar Lectionary For Christian Year 2017alwinalexanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quantum Jumping 1Dokument126 SeitenQuantum Jumping 1tvmedicine100% (14)

- Islam and Sacred SexualityDokument17 SeitenIslam and Sacred SexualityburiedcriesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corpus Malicious - The Codex of Evil (OEF) (10-2020)Dokument414 SeitenCorpus Malicious - The Codex of Evil (OEF) (10-2020)byeorama86% (22)

- Ancient China: GeographyDokument18 SeitenAncient China: GeographyInes DiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kurlander Hitlers Monsters, The Occult Roots of Nazism PDFDokument22 SeitenKurlander Hitlers Monsters, The Occult Roots of Nazism PDFMariano VillalbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Business Ethics of JRD by R M LalaDokument3 SeitenThe Business Ethics of JRD by R M LalasarasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zizek, Slavoj - The Violence of The FantasyDokument15 SeitenZizek, Slavoj - The Violence of The FantasyIsidore_Ducan_371100% (2)

- Mantra PurascharanDokument9 SeitenMantra Purascharanjatin.yadav1307100% (1)

- Jesus Is - : Student EditionDokument15 SeitenJesus Is - : Student EditionThomasNelson100% (1)

- Swami VivekanandasayingsDokument22 SeitenSwami VivekanandasayingshemantisnegiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bos StuffageDokument49 SeitenBos Stuffagejempr11890Noch keine Bewertungen

- HakDokument21 SeitenHakJules Vincent GuiaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mesopotamia and Egypt HandoutDokument3 SeitenMesopotamia and Egypt HandoutEcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Excerpts-Thou Shalt Not Bear False WitnessDokument9 SeitenExcerpts-Thou Shalt Not Bear False Witnesselirien100% (1)

- The Cherubim and The ThiefDokument10 SeitenThe Cherubim and The ThiefPete YoukhannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Session Zero WorkbookDokument26 SeitenSession Zero Workbookrecca297100% (4)

- Anton LaVeyDokument12 SeitenAnton LaVeyGnosticLuciferNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Questions For Humanities Subjs 3Dokument9 SeitenTest Questions For Humanities Subjs 3Leo S. LlegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambodian ArchitectureDokument3 SeitenCambodian ArchitectureDiscepolo100% (1)

- Prog2 02Dokument61 SeitenProg2 02klenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Grade World History: Chapter 4 Notes - The Rise of Muslim StatesDokument19 Seiten7 Grade World History: Chapter 4 Notes - The Rise of Muslim StatesNirpal MissanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chen Chang Xing S Teaching of The Correct Boxing SystemDokument5 SeitenChen Chang Xing S Teaching of The Correct Boxing SystemTibzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ayush Ug 2022 Allotted Data 12022023Dokument658 SeitenAyush Ug 2022 Allotted Data 12022023Arkaan khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 408373.osmanlis Islam and Christianity in Ragusan ChroniclesDokument18 Seiten408373.osmanlis Islam and Christianity in Ragusan Chroniclesruza84100% (1)

- In Hinduism, Each Day of A Week Is Dedicated To A Particular GODDokument1 SeiteIn Hinduism, Each Day of A Week Is Dedicated To A Particular GODRAJESH MENONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isha PrefaceDokument9 SeitenIsha PrefaceRama PrakashaNoch keine Bewertungen

- It Is A Truth Universally Acknowledged That A Single Man in Possession of A Good Fortune, Must Be in Want of A WifeDokument8 SeitenIt Is A Truth Universally Acknowledged That A Single Man in Possession of A Good Fortune, Must Be in Want of A WifeJaycelyn BaduaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filed: Patrick FisherDokument29 SeitenFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

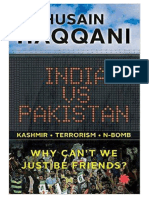

- (Hussain Haqqani) - India Vs Pakistan Why Can - T We Just Be FriendsDokument88 Seiten(Hussain Haqqani) - India Vs Pakistan Why Can - T We Just Be FriendsMohsin Ali Zain100% (1)