Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

EU Enlargement and Migration

Hochgeladen von

noeljeOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

EU Enlargement and Migration

Hochgeladen von

noeljeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

JCMS 2010 Volume 48. Number 2. pp.

373395

EU Enlargement and Migration: Assessing the Macroeconomic Impacts*

jcms_2056 373..396

RAY BARRELL

National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London

JOHN FITZGERALD

Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

REBECCA RILEY

National Institute of Economic and Social Research, London

Abstract

Enlargement of the European Union in May 2004 was followed by an increase in migration from the poorest of the central and eastern European New Member States (NMS) to other Member States. We consider the macroeconomic impacts of these migration ows across Europe, highlighting impacts in receiving and sending countries.

Introduction The expansion of the European Union (EU) in May 2004 to include ten New Member States (NMS) made it possible for workers from these countries to take up work in older Member States (EU-15). Some east to west migration was anticipated, but the pattern of immigration across the EU-15 differed from that expected; in part because of transitional restrictions on labour mobility imposed in many of the EU-15 (Boeri and Brcker, 2005). We illustrate the potential macroeconomic impacts of the migration ows that are likely to have resulted from EU enlargement.

* Many thanks to Dave Rae, to participants at the EUROFRAME meeting, Vienna, 26 January 2007, and an anonymous referee for their comments and to Alan Barrett, Adele Bergin, Dawn Holland, Ide Kearney, Iana Liadze, Yvonne McCarthy, Stefania Tomasini and Ewald Walterskirchen for providing data and references. Financial support from the European Commission and the NiGEM user group is gratefully acknowledged. None are directly responsible for the views presented here.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA

374

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

Clearly it is difcult to measure what migration might have happened had the EU enlargement in May 2004 not taken place, and hence to measure the change in migration from EU enlargement. There are relatively few data available on migration to be able to disentangle an explicit EU enlargement effect and the data that exist are not necessarily comparable across countries and time, or comprehensive. Bearing this in mind, we construct a set of numbers intended to mimic the change in migration from EU enlargement. Next, we assess the macroeconomic implications of these changes. We illustrate how these might depend on the labour market characteristics of migrants, the structure of sending and receiving economies, the skill composition and the nature of migration, whether it is temporary or permanent; rather than presenting a central case. Our tool for analysis is the National Institute Global Econometric Model (NiGEM), a global DSGE style model, which includes fully specied country models for most European countries (details are given in Appendix B). The next section describes the magnitude of population movements between the NMS and EU-15 that might be described as directly related to EU enlargement. Thereafter we discuss a simple model simulation exercise illustrating the macroeconomic impacts of these population movements, where cross-country differences arise primarily from the size of the migration shocks, but other structural factors are also important. We then illustrate the sensitivity of the results to assumptions about migrants. A nal section offers some conclusions. I. EU Enlargement and Migration In the majority of the EU-15 the legislative barriers facing NMS nationals, wanting to work or reside there, were little different following EU enlargement in 2004. Ireland, Sweden and the UK were alone in allowing NMS workers to move freely across national boundaries.1 Based on data available one year after this eastward expansion of the EU, Boeri and Brcker (2005) suggest the restrictions imposed in the EU-15 led to a diversion of NMS migrants from traditional destination countries bordering the NMS (Austria, Germany and Italy) to EU-15 countries with liberal immigration policies. More recent data reinforce that conclusion.

Limits on free labour mobility were allowed for a maximum of seven years. In 2006 Finland, Greece, Portugal and Spain removed all restrictions; six other countries adopted more liberal policies.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

375

NMS Migration to Countries with Less Restrictive Transitional Arrangements Table 1 shows estimates of the change in the two and a half years following EU enlargement in the number of NMS nationals or residents born in the NMS in Ireland, Sweden and the UK, the countries that adopted an open door policy towards NMS migrants. In the few years before accession the number of NMS nationals in these countries was broadly stable or rising slowly, so that the increase since then in the NMS population in these countries may reasonably be attributed to EU enlargement. Appendix A provides data sources and assumptions underlying the numbers in Table 1. The numbers suggest relatively little impact of EU enlargement in Sweden, with a signicantly larger impact in Ireland and the UK. Ireland in particular has experienced a large change in the number of NMS nationals present of 1.5 per cent of the total population; 2.2 per cent of the working age population. The UK is by far the most popular destination for NMS emigrants to the EU-15, but relative to population size this migration appears much smaller than for Ireland. The UK has seen strong immigration since the end of the 1990s, when net migration ows to the UK rose from around 50,000 to 150,000 per annum (ONS, 2008, Table 2.63). These developments have been attributed to an increasingly liberal immigration policy (Hatton, 2005) and demographic and economic factors (Mitchell and Pain, 2003). EU enlargement brought UK immigration to new heights, particularly for work reasons. Salt and Millar (2006) suggest that 2005 may have recorded the largest ever entry of foreign workers to the UK. It seems likely that the recent inow of NMS nationals to both Ireland and the UK largely reects a relatively liberal approach to NMS immigration. More difcult to explain are the apparent differences in NMS migration to the English-speaking countries vis--vis Sweden, which also operated an open door policy upon accession. The rate of unemployment in Ireland and the UK was little different from that in Sweden. The language may be a factor contributing to the popularity of the English-speaking countries. Table 1 illustrates the change in the stock of NMS migrants resident in certain EU-15 countries that is likely to have been associated with EU enlargement. This is different from the corresponding inow of NMS migrants, which tends to be much larger. In Ireland, 299,000 Personal Public Service Numbers were allocated between May 2004 and November 2006 to NMS nationals. This compares to an estimate of 96,000 NMS nationals resident in Ireland in the third quarter of 2006 (Irish Quarterly National

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

376

Table 1: Change in NMS Population Resident in Selected EU-15 Countries in the 21/2 Years following EU Enlargement May 2004 (thousands)

UK 13.5 3.0 8.0 15.7 29.7 167.5 27.3 0.3 265.0 0.45 0.72 0.3 0.0 0.3 0.0 0.1 6.0 1.6 1.1 9.3 0.11 0.16 6.1 0.8 6.0 1.4 2.0 62.0 3.2 1.2 82.7 0.10 0.15 2.2 0.3 2.2 0.5 0.8 30.9 1.2 0.4 38.5 0.07 0.10 24.7 5.0 18.1 22.7 43.5 310.6 38.7 3.1 466.4 0.24 0.38 0.18 0.99 1.27 0.81 0.72 0.16 Austria Germany Italy Total emigrant population % of total population % of working age pop. 0.34 0.55 0.26 1.44 1.87 1.18 1.00 0.22

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Ireland

Sweden

Czech Republic Estonia Hungary Latvia Lithuania Poland Slovakia Slovenia Total NMS % of total population % of working age population

2.5 1.1 1.9 4.8 9.6 37.9 5.1 0.0 62.8 1.49 2.17

0.1 -0.1 -0.3 0.3 1.3 6.3 0.2 0.1 8.0 0.09 0.14

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

Source: Authors calculations based on a variety of data sources detailed in Appendix A.

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

377

Household Survey).2 The UK Worker Registration Scheme suggests that 510,000 NMS nationals came to work as employees in the UK between May 2004 and September 2006. The UK Labour Force Survey suggests there were 265,000 NMS nationals resident in the UK in autumn 2006 who had arrived since accession (Blanchower et al., 2007). Despite issues of differential coverage, the differences in magnitude between the stock and ow data suggest NMS migration to Ireland and the UK has been of a temporary nature, with relatively short stays before return. NMS Migration to Traditional Destination Countries Data are more scant for the countries that might have received the majority of NMS migrants had labour been allowed to move freely across the EU-15. But it seems likely these countries experienced only a modest increase in immigration from the NMS as a result of EU enlargement. Data from the Austrian Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Labour suggest that in 2005 on average, 1,200 NMS migrants registered to work as employees in Austria every month. It would be difcult to attribute this to EU enlargement alone, since Austria saw signicant immigration from the NMS before accession. However, it seems quite likely that the numbers of NMS workers in Austria have increased more rapidly since then. From Poland alone, the number of wage and salary earners entering the Austrian labour force rose from 3,328 in 2003 to 4,309 in 2005 (January to mid-November). Further, Austrian Labour Market Service data show a near doubling of the number of self-employed NMS workers in Austria between 2003 and 2005, reecting a four-fold rise in self-employed Polish nationals and a 43 per cent rise in self-employed Hungarian nationals. We have taken these gures to imply an increase of 0.16 per cent in the population of working age in Austria due to EU enlargement, as shown in Table 1. We assume the near doubling of NMS nationals in Italy between January 2003 and January 2006 can be attributed to EU enlargement. However, we note the general increase in foreign nationals residing in Italy over this period (from 1.3 million to 2.4 million), suggesting the increase in the NMS population there may have occurred independently of EU enlargement. The number of migrants from Albania and Romania rose by 334,700 over this period, dwarng the 38,500 increase in the number of NMS migrants. Germany has traditionally been a popular destination for Polish emigrants. The number of Polish nationals residing in Germany averaged 318,000 in the

2

Irish Quarterly National Household Survey, Central Statistics Ofce http://www.ucd.ie/issda/datasetinfo/qnhs-details.htm.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

378

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

years 2001 to 2003, an increase of 8.9 per cent on the average in the three years before (OECD, 2008, Table B.1.5). In 2004 the number of Polish nationals in Germany fell back by 35,000 and it is possible to speculate that Polish emigrants substituted other destination countries for Germany with the new possibilities that arose upon EU accession (Fihel et al., 2006). However, this fall coincided with a change in the way these data were collected, resulting in a sharp decline in the measured population of all foreign nationals in Germany between 2003 and 2004. Between 2003 and 2006 these data show an increase in the number of Polish nationals resident in Germany of 10.6 per cent. Data from the Federal Statistical Ofce Germany suggest that the foreign population fell slightly from 7.342 million at the end of 2003 to 7.288 million at the end of 2004, remaining virtually unchanged in 2005. It is difcult to discern from these data any impact specically associated with EU enlargement. For the purposes here we assume that net migration to Germany from the NMS increased by an amount proportionally similar to that calculated for Italy and Austria. NMS Emigration Summing across the EU-15 countries listed in Table 1, the largest migrations from the NMS (relative to population size) have occurred from Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Slovakia (consistent with the ndings of Fihel et al., 2006). According to our calculations, 1.9 and 1.2 per cent, respectively, of the Lithuanian and Polish populations of working age were residing in the EU-15 at the end of 2006 because of accession. The magnitude of these shocks is not necessarily reected in the population statistics of the NMS (Eurostat, 2006, Table C-1); for example, according to these the population of Poland declined by 0.04 per cent between 2004 and 2005. Population numbers are of course inuenced by many factors, one of which may be increased immigration to some NMS from less afuent eastern European countries, a process which has been under way throughout the 1990s (Fihel et al., 2006). The discrepancy between the population statistics and the estimates in Table 1 may also reect the temporary nature of migration, leading to a situation where people leaving the NMS register for work in the EU-15 without giving up residency in their home country. Again, a comparison of migrant stocks and ows is suggestive of sizeable churn. Estimates of the number of Polish nationals leaving Poland for the EU in the rst couple of years after accession range from 500,000600,000 to one million (internal estimates provided by Centre for Migration Studies and Ministry of Labour, Poland). This compares to our estimate of the change in the stock of Polish nationals resident in the EU of a little more than 300,000.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

379

Figure 1: NMS Net Emigration and GDP per Head (2004)

13000 GDP per head in 2000 exchange rates and prices (euros) 12000 11000 10000 9000 8000 7000 Hungary 6000 5000 4000 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 Emigration to EU-15 (% of working age population) Slovakia Czech Republic Estonia Poland Latvia Lithuania

Slovenia

Source: Net emigration as shown in Table 1; GDP per head from NiGEM database.

Figures 1 and 2 plot net immigration from individual NMS to EU-15 countries, as shown in Table 1, against GDP per capita and unemployment, illustrating the correlation between emigration and economic conditions in the source country. Figure 1 (Figure 2) shows a negative (positive) correlation between emigration and GDP per capita (the unemployment rate) in the source country.3 The largest migrations have occurred from the poorest economies of the NMS, which also tend to have higher unemployment rates. Emigration from the poorer NMS following EU enlargement is signicant, although the numbers reported in Table 1 are not indicative of any mass migration from east to west. We note that the migration ow numbers associated with EU enlargement are likely to be substantially larger than the effects shown in Table 1. However, even if they are larger than shown in Table 1, the numbers are signicantly lower than was anticipated prior to enlargement in the case of free movement of labour across all the EU-15 (Boeri et al., 2002).

3

Blanchower et al. (2007) show correlations between NMS migration ows to the UK (measured as a percentage of NMS source country populations) and a range of well-being indicators in NMS source countries, including the unemployment rate, the employment rate and GDP per head.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

380

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

Figure 2: NMS Net Emigration and Unemployment (2004)

20 18 16 14 12 Lithuania 10 Czech Republic 8 Slovenia 6 4 2 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 Emigration to EU-15 (% of working age population) Hungary Estonia Latvia Poland Slovakia

Source: Net emigration as shown in Table 1; unemployment rate from NiGEM database.

II. Illustrations of Macroeconomic Impacts Extensive previous research on the economics of migration has highlighted the complex mechanisms through which changes in the labour force resulting from migration impact on the local economy. Borjas et al. (1997) show that the effect of migration on wage rates in recipient US states was masked by its effects on the movement of the native population within the US, and the identication of the true impact of migration on local wage rates required the use of a modelling approach accounting for these complex interactions.4 In this article we are not only concerned with the direct labour market impact of migration, but also consider the wider economic signicance of recent population movement in the EU. Reecting the complexity of the channels through which migration can impact on the economy, a suitable macroeconomic model is required to undertake this task. In this article we analyse the macroeconomic impacts on output, unemployment, productivity and ination of migration on the scale indicated in Table 1 using NiGEM, a large estimated quarterly model of the world economy, which uses a New-Keynesian

4

While later work by Borjas (2003) developed a methodology for directly estimating the regional effects of migration on wage rates, the complexity of the macroeconomic channels through which migration affects regional economies still remains of crucial importance for this study.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Unemployment rate (%)

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

381

framework with forward-looking agents where nominal rigidities slow adjustment to the long-run equilibrium. Most OECD countries are modelled separately; the rest of the world is modelled through regional blocks. All country models contain the determinants of domestic demand, trade volumes, prices, current accounts and net assets. Domestic demand, aggregate supply and the external sector are linked via the wage-price system, income and wealth, nancial and government sectors and competitiveness. The external sector links the domestic economy to the rest of the world. Details of this model are given in Appendix B. Crucial in any analysis of the macroeconomic impacts of migration are the ways in which migrants enter the production function, their inuence on wage-setting and the time horizon considered. In this section we assume migrant and native populations in the receiving countries are equally productive and perfect substitutes, and that their productivity rises at the same rate over time. Upon remigration to the home country individuals are assumed to have the same productivity as natives there. An alternative interpretation is that there is no remigration. We assume the structural parameters of the wage bargain are unaffected by migration. This means that in our model the migrant population inuences the supply side of the labour market via its effects on the size of the population of working age, unemployment and productivity alone. We discuss and relax these assumptions in later sections. With these assumptions in place the effects of migration on productivity, average wages and unemployment are very much dependent on our assumptions about the elasticity of the supply of capital and the dynamics of capital adjustment (see the discussion in Dustmann et al., 2008). All the economies we analyse are small and open and hence in the long run the supply of capital is perfectly elastic. However, adjustment costs and wage rigidities mean that the capital stock does not change immediately to the new long-run equilibrium. The period of adjustment for the business sector capital stock varies by country, but is typically around ten years (similar to the assumptions in Ottaviano and Peri, 2006). Public infrastructures (such as transport) and the housing stock adjust more slowly. When capital is xed, a smaller elasticity of substitution between capital and labour increases the magnitude of the labour market impacts of migration (Borjas, 2003). Our model assumes a CES technology with elasticity of substitution between capital and labour of around 0.5, which ts the data better than the standard Cobb-Douglas assumption. In modelling the effects of EU enlargement we assume this changes the population from the second quarter of 2004 and that the migrant stock reaches the levels reported in Table 1 after two and a half years. Thereafter, as a working assumption, we assume the number of migrants remains constant.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

382

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

This implies that the migrant population does not necessarily grow in line with the rest of the host country population, which seems appropriate given the transitory nature of migration and stationary population projections for the majority of central and eastern European countries. The latter means that our assumptions imply a constant emigrant stock in proportion to the size of the sending countries. The change in the population is implemented exogenously, ignoring feedback from the macroeconomic implications of migration to the size or direction of migration. NiGEM is used with all its defaults in place, including forward-looking nancial markets, policy feedbacks maintaining budget decit targets (Barrell and Sefton, 1997) and ination targets (Barrell et al., 2006). Simulation Results The simulation results show the possible effects of NMS migration to the EU-15 associated with enlargement; illustrated in Figure 3 for Lithuania, Poland, Ireland and the UK. Appendix Tables C1C6 give detailed results for individual years 20059 and 2015. They do not take account of the wider effects of enlargement. Conditional on the assumptions described above, the effect of a net increase in Polish emigration of around one-third of a million people of working age is to reduce output in Poland permanently by around 1 per cent. The reduction in output comes as a result of having fewer workers, but is not one for one because the capital stock does not fully adjust, leaving the capitallabour ratio permanently higher. In the longer term, business sector capital adjusts downward to match the decline in the labour force. Both public and housing capital enter the production function and, since these do not adjust fully, productivity in Poland is permanently higher by around 1/3 per cent. Qualitatively the effects on output and productivity are similar for the other NMS countries. In Ireland and the UK the reverse pattern is observed. The increase in the labour force raises potential output, and in the longer term output rises to match this increase. Again the match is not one for one, since productivity changes. In Ireland and the UK productivity falls as public sector infrastructure and the housing stock fail to rise, by assumption, to maintain the ratio of capital to labour. Intuitively this assumption seems more restrictive for the receiving than for the sending countries, where one assumes emigration would not lead to an immediate dismantling of public infrastructure. For the receiving countries it seems more likely that public sector capital would adjust to accommodate the increased population, in which case the GDP effects would be larger in the EU-15 than our simulations suggest, and

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

383

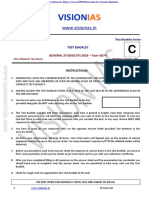

Figure 3: Macroeconomic Impacts of Migration within the EU

GDP 2 1.5 GDP per capita

% difference from base

% difference from base

1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5

07 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 05 20 20 06

1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1

07 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 20 05 20 06

-2

-1.5

20

20

20

20

Ireland

UK

Inflation

Lithuania

Poland

Ireland

UK

Lithuania

Poland

Current account balance 0.4

1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1

20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 06 20 20 20 07 05

% point difference from base

% point difference from base

0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8

20 05 20 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

Ireland

UK

Lithuania

Poland

Ireland

UK

Lithuania

Poland

Unemployment 1.5 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1

20

Productivity

% point difference from base

1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5

08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 06 07 05 20 20 20 20

% difference from base

Ireland

UK

Lithuania

Poland

Source: Authors calculations. Notes: Values shown at year end. We do not include remittances in our balance of payments estimates.

productivity would be less depressed. In the longer term output in the UK is 2 /3 per cent higher than it would otherwise be. In Ireland output is higher by 1.7 per cent reecting mainly the size of the migration shock.5 We nd a short-term effect on unemployment and ination. Short-term labour market equilibrium changes due to adjustment costs and the assumption that migration is initially unanticipated. This means that the capital stock required for the additional workers is not in place when they arrive. Hence,

5

The shock is constant in absolute size after 2006, hence representing a smaller per cent increase in the Irish workforce in 2015 than in 2006.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

05 20

20

20

06

07

Ireland

UK

Lithuania

Poland

384

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

labour demand is unchanged at given wages. As a consequence, in the short run, new migrants either displace existing workers or become unemployed. Higher unemployment reduces negotiated wages and therefore the average wage level as compared to where it would otherwise have been. In turn the amount of labour demanded and the level of employment rise (the labour supply curve moves down the labour demand curve). The effect on unemployment in the receiving countries is temporary. The process of adjustment involves lower ination in comparison to base, given the monetary policy assumptions. Lower wages dampen ination temporarily inducing lower interest rates, and the exchange rate jumps down as a consequence. A reduction in average productivity occurs because labour has become more abundant and cheaper so that companies hire more and employment increases. As this is associated with an increase in output, higher levels of capital utilization raise the rate of return on existing capital. Household income and consumption rise because the increase in employment more than offsets the initial decline in wages. The combination of rising consumption and increased protability leads companies to raise capital investment, eventually restoring productivity to around its initial level or to a new steady state. The short-term effect of the population changes is to raise unemployment in Ireland (UK) by one (quarter) percentage point on average between 2006 and 2008; and to reduce ination by 0.7 (0.1 to 0.2) percentage points. The impact comes through more quickly in Ireland because the exchange rate does not adjust downwards as much as in the UK. This is because the reduction in Irish ination has noticeably less impact on interest rates than in the UK as the ECB targets euro area ination, which falls less than that in Ireland. The short-term pattern of higher unemployment and lower ination in the EU-15 countries is mirrored by lower unemployment and higher ination in the accession countries, in comparison to base.6 On average, in the years 2006 to 2008, unemployment is reduced by 0.8 (0.4) percentage points in Lithuania (Poland). The downward shift in unemployment is permanent for Lithuania.7 All the economies considered here are small and open. Hence, the change in the rate of return on capital causes a capital inow or outow, until the rate of return is restored at world levels. The return to capital increases in countries that are net recipients of migrants, causing a capital inow. The extra investment is nanced by a balance of payments decit, which comes in advance of extra income. As illustrated in Figure 3, the current account in

6 7

Fertig (2003) reaches a similar conclusion about the pattern of unemployment effects. The downward shift in unemployment is also permanent for some of the other smaller and less developed economies, i.e. Estonia, Latvia and Slovakia, as the estimation behind our model of their labour markets embeds a reservation wage, which rises over time, but has little endogenous productivity effect. Hence, a rise in productivity raises employment.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

385

Ireland and the UK deteriorates. The deterioration is more marked in Ireland because the shock is bigger, the Irish economy is more open, and there is a smaller exchange rate offset than in the UK economy. The NMS countries see an improvement in the current account. Following a small reduction in GDP per capita in the short term in EU-15 receiving countries, GDP per capita rises in the longer term (Figure 3); similar to Iakova (2007).8 The short-term reduction comes about as it takes time for the capital stock to adjust to the inow of labour and for the additional labour to be absorbed into employment. In the longer term GDP per capita rises as the population of working age increases relative to the population as a whole. In the NMS GDP per capita generally rises relative to base. The reduction in the population of working age relative to the population as a whole will tend to depress GDP per capita, but the rise in productivity and the reduction in unemployment more than offset this change. Differences in macroeconomic effects across countries mostly reect differences in the magnitude of the migration changes. But there are other structural differences that determine the prole of effects. We have highlighted the importance of the composition of the capital stock. All else being equal, the larger the share of public sector and housing capital in the aggregate capital stock, the more pronounced the effect on productivity and the less pronounced the effect on GDP. Also, the more capital intensive aggregate production is, the slower the economy adjusts to long-run equilibrium. Other factors of importance include the openness of the economy, which is positively correlated with the magnitude of current balance effects, and the dynamics of the labour market. The effects of migration on unemployment (ination) are more (less) pronounced in countries with more sluggish labour markets. III. Migrant Labour Market Characteristics, Learning Effects and Remittances In the section above we assumed all population groups in a particular country exhibit the same labour market characteristics. Here we reconsider some of these assumptions. First, that the average NMS immigrant is identical to the average worker in the EU-15, which is clearly rejected by the data. The impacts of migration on the labour market and the economy crucially depend on the skill mix of immigrants versus natives in the host country (see, for example, Borjas, 1999). Second, we re-examine the effects under different

8

Simulating the macroeconomic implications of NMS migration to the UK using the IMFs Multimod, Iakova (2007) nds a similar time prole for the effects on GDP per capita. There, a short-run reduction in GDP per capita is a result of average productivity differentials between young migrant workers and native workers. This effect disappears over time as migrants age and their productivity increases.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

386

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

assumptions about adjustment of the capital stock and labour demand. Last, we consider the assumption that returning migrants are identical to native workers in the home country. Skills and Labour Market Participation Recent NMS immigrants in the UK are concentrated in low-skill occupations, with 62 per cent of this group working in elementary or process, plant and machinery occupations in comparison to 19 per cent of the population as a whole (Riley and Weale, 2006). This does not necessarily imply that NMS migrants are low skilled. Indeed, Drinkwater et al. (2006) nd that Polish workers who have arrived in the UK since enlargement achieve signicantly lower returns to their education than other residents. A similar pattern may be observed in Ireland. NMS nationals there are much more likely to be employed in industries that have a large share of low-skilled jobs (nonagriculture production industries, hotels and restaurants, construction) than other residents (Irish Quarterly National Household Survey). Again it is likely that the jobs immigrants take are below their skill levels. The studies by Barrett et al. (2006) and Barrett and McCarthy (2007) suggest that migrants in Ireland (particularly from non-English-speaking countries) tend to be employed in occupations that are not commensurate to their skill levels. As Fihel et al. (2006) point out, it is possible that the tendency for NMS migrants to take up relatively low-skilled jobs reects the transitory nature of this migration. In Figure 4 we illustrate the GDP and ination impacts of NMS migration in Ireland and the UK under different assumptions about immigrant relative to native productivity. In the lower productivity case the average NMS job is 74 per cent as productive as the average native job, calculated by comparing the employment weighted average of standard wage rates in three main occupation groups between NMS migrants and others (UK Labour Force Survey, as reported in Riley and Weale, 2006). In this calculation immigrants and natives are assumed equally productive and perfect substitutes in the same job. If NMS workers are more productive than native workers in the same job, for example, because NMS workers in the same job are likely to be on average more highly skilled, our calculation may exaggerate the productivity differential. The estimated 26 per cent productivity differential is within the range of gures provided by estimates of migrant pay penalties; for Polish workers in the UK (Drinkwater et al., 2006) and for non-English speaking migrants in Ireland (Barrett and McCarthy, 2007). The migrant pay penalty may disappear over time as migrants adapt to the destination country and nd jobs more commensurate to their skill levels or as migrants in temporary arrangements

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

387

Figure 4: Macroeconomic Impacts of Migration within the EU under Different Assumptions about Immigrants versus Natives in Receiving Countries

Ireland: GDP

1.8 0.4

Ireland: Inflation

% point difference from base

% difference from base

1.6 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0

20 05 20 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2

05 20 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 20

identical lower productivity lower productivity and higher participation

identical lower productivity lower productivity and higher participation

UK: GDP

1.8 0.4

UK: Inflation

% point difference from base

05 20 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

% difference from base

1.6 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0

20

0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2

05 20 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 06 20

identical lower productivity lower productivity and higher participation

identical lower productivity lower productivity and higher participation

Source: Authors calculations.

return to their home country. For simplicity we assume that all migration from the NMS is transitory and therefore that the pay penalty is constant over time. We also show how our results change with the assumption about immigrants labour market participation. The data suggest that NMS migrants are more likely to be in the labour force than others in Ireland and the UK, consistent with the notion that migration is motivated by economic reasons. For the UK (Ireland) the difference in participation rates between NMS migrants and the remaining population of working age is estimated at 7 (15) percentage points. As illustrated in Figure 4 the differential productivity assumption reduces the GDP effect of NMS migration in both Ireland and the UK. Because migration in this instance raises capacity by less than if there were identical productivity, the dampening effect on ination of migration is more subdued. The need for additional capital is also lower, since the reduction in average productivity reduces the equilibrium ratio of capital to labour, and the impact on the current account balance is therefore more muted. Also illustrated in

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

388

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

Figure 4, the effect of higher labour market participation amongst migrants amplies the shock to the labour force for a given shock to the population of working age, and thus the magnitudes of the ination, GDP, unemployment and current account effects. Capital and Labour Demand The short-term effects on unemployment from unanticipated migration in this analysis apparently contradict the ndings of several other studies (see review in Blanchower et al., 2007). Gilpin et al. (2006) nd no relationship between unemployment changes and the rise in NMS migration across UK local authority districts, although this may be due in part to induced onward migration (Borjas, 2003; Hatton and Tani, 2005). One explanation for the apparent lack of unemployment effects is that immigrants are imperfect substitutes for native workers (Ottaviano and Peri, 2006; Manacorda et al., 2006). If immigrant and native workers are complements, immigration might increase aggregate labour demand also in the short run. Immigration to less capital-intensive sectors provides another explanation. It is also possible that NMS migrants have increased the exibility of host economy labour markets, which would lead to faster adjustment of wages and output and, potentially, a reduction in equilibrium unemployment in the receiving countries. As discussed in the previous section, NMS migrants to the UK have typically found low-skilled jobs. On the one hand this should increase the magnitude of short-term unemployment effects, because lowskill wages in the UK exhibit less downward exibility (Riley and Young, 2007). However, there is evidence to suggest that immigrants in the UK have increased the exibility of wage-setting, particularly in low-skilled occupations (Nickell and Saleheen, 2008). This may be reinforced by the temporary nature of NMS migration. With particular reference to the results obtained for Ireland, we note that one or a combination of these factors is likely to be important. The Irish unemployment rate remained unchanged in the face of very large migration ows upon accession. If the simulation results were taken at face value the Irish unemployment rate would have fallen below 3 per cent in the absence of EU enlargement, something that has never been experienced in recent times and is well below the experience of other seemingly fully employed economies. The fact that unemployment did not change much, while wages did, could indicate exceptional labour market exibility or that NMS immigrants simply displaced immigrants from other locations, such that immigration at an aggregate level was anticipated. The latter may well have been important for Ireland where the authorities changed policy on issuing work permits to

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

389

people from non-EU countries as a result of the inux from the NMS. Immigration from outside the EU fell by a small amount after enlargement, though nothing like the increase in immigration from the NMS. Alternatively businesses may have anticipated that immigrants would have been found from somewhere and invested accordingly. Figure 5 shows the macroeconomic impacts of NMS migration for Ireland, as in Figure 3, alongside the impacts that would result if, for given levels of capital, labour demand temporarily increased to match the increase

Figure 5: Macroeconomic Impacts of Migration within the EU under Different Labour Demand Curve Assumptions (Ireland)

GDP 2 1.8 1.6 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0

13 10 12 11 05 07 08 20 06 09 14 15 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20

Productivity 1 % difference from base 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 -1.5 -2 -2.5

05 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20 20 20

% difference from base

unchanged

temporary increase

unchanged

temporary increase

Inflation 1 % point difference from base 0.5 0 % difference from base 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2 -1.4

07

GDP per capita

-0.5 -1

-1.5

10 14 15 11 05 20 06 20 07 20 09 20 08 20 12 20 13 20 20 20 20 20

11

09

13

05

06

08

20 10

20 12

20

20

14 20

unchanged

temporary increase

unchanged

temporary increase

Unemployment 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6

20 05 20 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15

Current account balance 0 % point difference from base -0.1 -0.2 -0.3 -0.4 -0.5 -0.6 -0.7 -0.8

05 06 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 20 20 07

% point difference from base

unchanged

temporary increase

unchanged

temporary increase

Source: Authors calculations. Notes: Values shown at year end. We do not include remittances in our balance of payments estimates.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

20

20

20

20

20

20

15

390

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

in labour supply from migration. This might occur when, for example, migrant workers initially nd work in less capital-intensive occupations where the additional labour supply is absorbed more quickly or if native and migrant workers are in some way complementary in the production process (in the short term) as discussed above. In the long run the two scenarios in Figure 5 are identical, but they differ in the short run. Comparing the scenario where the labour demand curve shifts upwards to the scenario with unchanged short-run labour demand: GDP rises more quickly (in the rst four years GDP growth is a quarter percentage point higher), ination is marginally less as the output gap is reduced, unemployment is much lower, productivity growth slows more markedly (because of the expansion in less capital-intensive production), but the short-run dip in output per capita is less marked because of the stronger increase in employment. Learning Effects and Remittances A number of studies suggest the productivity of emigrants returning to their home country is above that of natives there (Barrett and OConnell, 2001; Co et al., 2000; Mayr and Peri, 2008). For example, emigrants may have developed useful networks, language skills and new ways of working. Figure 6 illustrates the GDP and ination effects of the population changes in Table 1 in Lithuania and Poland when returnees are no different from natives (as above) and when returnees to the home country are 10 per cent more productive than natives. In this scenario the ow of returnees equals the stock of emigrants per annum, consistent with the stock and ow gures observed for Poland, Ireland and the UK. When returnees come back with enhanced productivity, the negative effect on GDP from the reduction in the labour force gradually reverses as the stock of more productive workers builds up. The expansion of capacity in the longer term means that ination is lower in comparison to the case where workers are identical. The analysis here assumes that migrants remittances to the home country are as natives remittances in the host country to the source country. Intuitively this seems an unlikely description of reality. Fihel et al. (2006) suggest that remittances from NMS migrants are likely to be large, consistent with the relatively transitory nature of NMS migration. Increased remittances payments from the EU-15 to NMS countries have obvious implications for the balance of payments. Remittances payments will increase household incomes in the NMS, but the effects on incomes in the EU-15 will be relatively small, since incomes are signicantly higher there. The effect of higher incomes in the NMS will be reected in higher GNP, rather than in higher GDP, and will tend to increase consumption in the NMS. The latter will tend to offset the

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

391

Figure 6: Macroeconomic Impacts of Migration within the EU under Different Assumptions about Returning Emigrants versus Natives in Sending Countries

Lithuania: GDP 0.2 % point difference from base % difference from base 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2 0.4 Lithuania: Inflation

0 20 5 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2

20

identical

higher productivity Poland: GDP

0.2 % point difference from base 0 % difference from base -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 -0.6 -0.8 -1 -1.2

0 20 5 06 20 07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

20

identical

higher productivity

Source: Authors calculations.

downward effect on GDP in these countries in the short run, but should have little long-run effect on GDP. Conclusion In this article we considered the possible effects on key macroeconomic variables from NMS migration associated with EU enlargement. Based on a variety of data sources we suggest that immigration from the NMS to the EU-15 in the two and a half years following accession was probably strongly inuenced by the different policy stances adopted in individual EU-15 countries. Measured in terms of permanent population changes NMS migration has not occured on the mass scale that some anticipated prior to enlargement (see, for example, Boeri et al., 2002, and the studies summarized in Barrell et al., 2004, Table 4.5), although temporary population movements have been substantial. The concentration of migration amongst the poorest of the NMS and the English-speaking members of the EU-15 imply that the macroeconomic impacts of EU accession and migration are likely to be noticeable in these countries. However, in comparison to the immigration that normally

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

identical higher productivity

05

20

20

20

06

07 20 08 20 09 20 10 20 11 20 12 20 13 20 14 20 15 20 16 20 17 20 18 20 19 20 20

identical higher productivity Poland: Inflation

05 20

20

20

06

392

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

occurs from countries outside the EU, the migration associated with the enlargement of the EU in May 2004 has proved fairly modest. Our analysis highlights the importance of public infrastructure and housing in determining the macroeconomic impacts of NMS migration. While these can and will adjust in the receiving countries there are temporary, though possibly quite long-lasting, effects on prices or shadow prices (for example, congestion). Duffy et al. (2005) nd that high levels of immigration put upward pressure on house prices and rents reducing the benets from coming to Ireland at the margin. It also has welfare implications for residents and has a dampening effect on aggregate productivity. Interestingly, Spain, where the annual inow of foreign nationals has increased from 99,000 in 1999 to 803,000 in 2006,9 and the UK, have experienced a period of slow productivity growth, much as might be expected on the basis of the analysis discussed here. The degree of openness, migrant skills, labour market adjustment speeds and the remit of the central bank (in particular whether or not interest rates are set with reference to national or euro area ination) also determine the way in which NMS migration and EU enlargement affects the macroeconomy. But it is probably the size of the migration that is most important in determining the macroeconomic impacts of EU enlargement and migration. This may largely have been an issue of policy.

Correspondence: Rebecca Riley National Institute of Economic and Social Research 2 Dean Trench Street, Smith Square London SW1P 3HE, United Kingdom Tel +44 20 7222 7665 Fax +44 20 7654 1900 email r.riley@niesr.ac.uk

References

Anderton, R., and Barrell, R. (1995) The ERM and Structural Change in European Labour Markets: A Study of 10 Countries. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, Vol. 131, No. 1, pp. 4766. Barrell, R., and Davis, E.P. (2007) Financial Liberalization, Consumption and Wealth Effects in 7 OECD countries. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, pp. 25467. Barrell, R., and Sefton, J. (1997) Fiscal Policy and the Maastricht Solvency Criteria. Manchester School, Vol. 65, No. 3, pp. 25979.

9

OECD, International Migration Outlook, 2008.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

393

Barrell, R., Hall, S.G., and Hurst A.I.H. (2006) Evaluating Policy Feedback Rules Using the Joint Density Function of a Stochastic Model. Economics Letters, Vol. 93, No. 1, pp. 15. Barrell, R., Holland, D., and Pomerantz, O. (2004) Integration, Accession and Expansion. NIESR Occasional Paper, No. 57. Barrett, A. and McCarthy, Y. (2007) Immigrants in a Booming Economy: Analysing their Earnings and Welfare Dependence. Labour, Vol. 21, No. 45, pp. 789 808. Barrett, A. and OConnell, P. (2001) Is There a Wage Premium for Returning Irish Migrants? Economic and Social Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 121. Barrett, A., Bergin, A. and Duffy, D. (2006) The Labour Market Characteristics and Labour Market Impacts of Immigrants in Ireland. Economic and Social Review, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 126. Bif, G. (2007) How to Balance Selective Migration and (Re)training Local Workers? The Case of Austria. Paper presented at Euroframe meeting, Vienna, 26 January. Blanchower, D., Saleheen, J. and Shadforth, C. (2007) The Impact of the Recent Migration from Eastern Europe on the UK Economy. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 2615. Boeri, T., and Brcker, H. (2005) Migration, Co-ordination Failure and EU Enlargement. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 1600. Boeri, T., Bertola , G., Brcker, H., Coricelli, F., de la Fuente, A., Dolado, J., FitzGerald, J., Garibaldi, P., Hanson, G., Jimeno, J., Portes, R., Saint-Paul, G. and Spilimbergo, A. (2002) Whos Afraid of the Big Enlargement? CEPR Policy Paper, No. 7. Borjas, G. (1999) The Economic Analysis of Immigration. In Ashenfelter, O. and Card, D. (eds) Handbook of Labor Economics Volume 3A (Elsevier: North Holland). Borjas, G. (2003) The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Re-examining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118, No. 4, pp. 133574. Borjas, G., Freeman, R., and Katz, L. (1997) How Much do Immigration and Trade Affect Labour Market Outcomes? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 1997, No. 1, pp. 190. Co, C., Gang, I. and Yun, M. (2000) Returns to Returning. Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 5779. Drinkwater, S., Eade, J. and Garapich, M. (2006) Poles Apart? EU Enlargement and the Labour Market Outcomes of Immigrants in the UK. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 2410. Duffy, D., FitzGerald, J. and Kearney, I. (2005) Rising House Prices in an Open Labour Market. Economic and Social Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 25172. Dustmann, C., Glitz, A., and Frattini, T. (2008) The Labour Market Impact of Immigration. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 478 95.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

394

RAY BARRELL, JOHN FITZGERALD AND REBECCA RILEY

Eurostat (2006) Population Statistics, 2006 Edition. European Commission. Fertig, M. (2003) The Impact of Economic Integration on Employment An Assessment in the Context of EU Enlargement. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 919. Fihel, A., Kaczmarczyk, P. and Oklski, M. (2006) Labour Mobility in the Enlarged European Union: International Migration from the EU8 countries. CMR Working Paper, No. 14.72, Centre of Migration Research, Warsaw. Gilpin, N., Henty, M., Lemos, S., Portes, J. and Bullen, C. (2006) The Impact of Free Movement of Workers from Central and Eastern Europe on the UK Labour Market. Working paper No. 29, Department for Work and Pensions. Hatton, T. (2005) Explaining trends in UK immigration. Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 71940. Hatton, T. and Tani, M. (2005) Immigration and Inter-Regional Mobility in the UK, 19822000. Economic Journal, Vol. 115, pp. 34258. Iakova, D. (2007) The Macroeconomic Effects of Migration from the New European Union Member States to the United Kingdom. IMF Working Paper, 07/61. Manacorda, M., Manning, A. and Wadsworth, J. (2006) The Impact of Immigration on the Structure of Male Wages: Theory and Evidence from Britain. CEP Discussion Paper, No. 754. Mayr, K., and Peri, G. (2008) Return Migration as Channel of Brain Gain. CReAM Discussion Paper, No. 00804. Mitchell, J. and Pain, N. (2003) The Determinants of International Migration into the UK: A Panel Based Modelling Approach. NIESR Discussion Paper, No. 216. Nickell, S., and Saleheen, J. (2008) The Impact of Immigration on Occupational Wages: Evidence from Britain. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Working Paper, No. 08-6. OECD (2008) International Migration Outlook. SOPEMI. Ofce for National Statistics (2008) International Migration. Series MN No. 33, 2006 Data. Ottaviano, G. and Peri, G. (2006) Rethinking the Effects of Immigration on Wages. NBER Working Paper, No. 12497. Salt, J. and Millar, J. (2006) Foreign Labour in the United Kingdom: Current Patterns and Trends. Labour Market Trends, Vol. 114, No. 10, pp. 33555. Riley, R. and Weale, M. (2006) Immigration and its Effects. National Institute Economic Review, No. 198, pp. 49. Riley, R. and Young, G. (2007) Skill Heterogeneity and Equilibrium Unemployment. Oxford Economic Papers, Vol. 59, pp. 70225.

Supporting Information Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article: Appendix A. Migration Data Appendix B. The Structure of the Model

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

EU ENLARGEMENT AND MIGRATION

395

Appendix C. Detailed Simulation Results Table C1. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on GDP (% difference from base) Table C2. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on Ination (% point difference from base) Table C3. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on Unemployment (% point difference from base) Table C4. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on the Current Account (% point difference from base) Table C5. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on Productivity (% difference from base) Table C6. EU Enlargement and Migration: Impacts on GDP per Capita (% difference from base) Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

2010 National Institute of Economic and Social Research Journal compilation 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- TreePlan Guide 177Dokument22 SeitenTreePlan Guide 177Amanda DuranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice+Questions+for+Lectures+1 4Dokument5 SeitenPractice+Questions+for+Lectures+1 4noeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Questions For Lecture 5Dokument3 SeitenPractice Questions For Lecture 5noeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDA2013 Week0 WindowsExcel2003 BeginnersDokument8 SeitenDDA2013 Week0 WindowsExcel2003 BeginnersnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDA2013 Week7 WindowsExcel2003 RiskAnalysisDokument6 SeitenDDA2013 Week7 WindowsExcel2003 RiskAnalysisnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio Optimisation With Solver James W. Taylor: Excel 2003 GuideDokument6 SeitenPortfolio Optimisation With Solver James W. Taylor: Excel 2003 GuidenoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Install AddinDokument11 SeitenHow To Install AddinnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDA2013 Week4 WindowsExcel2003 RegressionDokument8 SeitenDDA2013 Week4 WindowsExcel2003 RegressionnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ejkm Volume5 Issue4 Article137Dokument12 SeitenEjkm Volume5 Issue4 Article137noeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- JLP Report and Accounts 2013Dokument100 SeitenJLP Report and Accounts 2013noeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDA2013 Week4 3 WindowsExcel2010 Regression-1Dokument8 SeitenDDA2013 Week4 3 WindowsExcel2010 Regression-1noeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Model Canvas PosterDokument1 SeiteBusiness Model Canvas Posterosterwalder75% (4)

- DDA2013 Week3 0 ContentsDokument2 SeitenDDA2013 Week3 0 ContentsnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DDA2013 Week2 WindowsExcel2003 StatsIntroDokument8 SeitenDDA2013 Week2 WindowsExcel2003 StatsIntronoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Opportunities in Russian HealthcareDokument5 SeitenUS Opportunities in Russian HealthcarenoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Looking Inside For Competitive Advantage: Executive OverviewDokument14 SeitenLooking Inside For Competitive Advantage: Executive OverviewPistoph SexuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic Change and Regional Competitiveness - The Effects of Immigration and AgeingDokument22 SeitenDemographic Change and Regional Competitiveness - The Effects of Immigration and AgeingnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Of Brain Drain and Policy ResponsesDokument27 SeitenOf Brain Drain and Policy ResponsesnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Limits to Growth report analyzed humanity's ecological footprintDokument3 SeitenThe Limits to Growth report analyzed humanity's ecological footprintnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Snapshot Report On Russia's Healthcare Infrastructure IndustryDokument6 SeitenSnapshot Report On Russia's Healthcare Infrastructure IndustrynoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic BusinessDokument3 SeitenDemographic BusinessnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Demographic Effects of International Migration in Europe - AnnotatedDokument25 SeitenThe Demographic Effects of International Migration in Europe - AnnotatednoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shortage of Workforce and ImmigrationDokument25 SeitenShortage of Workforce and ImmigrationnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pricing Reimbursment in Brazil and RussiaDokument0 SeitenPricing Reimbursment in Brazil and RussianoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- DUO Russia PrivateHealthDokument74 SeitenDUO Russia PrivateHealthnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic Change, Migration, and Climate Change InteractionsDokument13 SeitenDemographic Change, Migration, and Climate Change InteractionsnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic Change and Regional Competitiveness - The Effects of Immigration and AgeingDokument22 SeitenDemographic Change and Regional Competitiveness - The Effects of Immigration and AgeingnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Europe's Migration Agreements Towards SouthDokument34 SeitenEurope's Migration Agreements Towards SouthnoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Migration and Its Downturn, Assessing The Impact of The Global Financial Downturn - AnnotatedDokument10 SeitenInternational Migration and Its Downturn, Assessing The Impact of The Global Financial Downturn - AnnotatednoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migration and Intergenerational Replacement in EuropeDokument27 SeitenMigration and Intergenerational Replacement in EuropenoeljeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5784)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- List of Recessions in The United StatesDokument8 SeitenList of Recessions in The United StatesSushil JodveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3 - Poverty As ChallengeDokument4 SeitenChapter 3 - Poverty As ChallengeJag Prasad ChaturvediNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supporting Documents: Please Attach Certified Copies of The Following DocumentsDokument1 SeiteSupporting Documents: Please Attach Certified Copies of The Following DocumentskfctcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 14, Section 1 Textbook NotesDokument2 SeitenChapter 14, Section 1 Textbook NotesSonny AnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guy Standing 2011, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic. 19.99, Pp. 198, PBKDokument5 SeitenGuy Standing 2011, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic. 19.99, Pp. 198, PBKPaloma BNoch keine Bewertungen

- The epic bust of Atlantic City's gambling economyDokument27 SeitenThe epic bust of Atlantic City's gambling economyNacho GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Offshoring The Next Industrial RevolutionDokument2 SeitenSummary Offshoring The Next Industrial RevolutionVicky RajoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to Become a Millionaire: Dr. Ben Phiri on Taking Risks, Embracing Opportunities, and Achieving Financial FreedomDokument4 SeitenHow to Become a Millionaire: Dr. Ben Phiri on Taking Risks, Embracing Opportunities, and Achieving Financial FreedomPacharo ShabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Exam Econ 2Dokument8 SeitenFinal Exam Econ 2Ysabel Grace BelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- BAM RA20 enDokument334 SeitenBAM RA20 ensoukaina écoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Productivity 2 Anu QuestDokument34 SeitenProductivity 2 Anu QuestAnnapurna SrinathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Set #2 Answer Key Provides Insights into Macroeconomic ConceptsDokument4 SeitenProblem Set #2 Answer Key Provides Insights into Macroeconomic ConceptsEUGENE AICHANoch keine Bewertungen

- Factory Leave Records 2009-2012Dokument1 SeiteFactory Leave Records 2009-2012chirag bhojakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Keynesianism FailedDokument27 SeitenWhy Keynesianism FailedThanos Drakidis100% (1)

- Social InsuranceDokument7 SeitenSocial InsuranceRia Shay100% (1)

- Vision IAS CSP 2019 Test 24 Questions PDFDokument18 SeitenVision IAS CSP 2019 Test 24 Questions PDFmanjuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Application Form For Tin IDDokument3 SeitenApplication Form For Tin IDShanaia BualNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECO501 Business EconomicsDokument12 SeitenECO501 Business EconomicsTrungKiemchacsuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intermediate Macroeconomics I Foundations of Aggregate Income DeterminationDokument3 SeitenIntermediate Macroeconomics I Foundations of Aggregate Income Determinationtanishkaparate2005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Answer To Discussions Question of Chapter 1 of Development EconomicsDokument3 SeitenAnswer To Discussions Question of Chapter 1 of Development Economicshakseng lyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Econ 110 Problem Set - PPF, Scarcity & EfficiencyDokument8 SeitenEcon 110 Problem Set - PPF, Scarcity & EfficiencyJoe OstingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpc1123 Principles of Economics s2 0818Dokument13 SeitenBpc1123 Principles of Economics s2 0818Nur Zarith HalisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reinert Intra IndustryDokument16 SeitenReinert Intra IndustrychequeadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour Market Modelling and The Urban Informal Sector: Theory and EvidenceDokument23 SeitenLabour Market Modelling and The Urban Informal Sector: Theory and EvidenceOmar Alburqueque ChávezNoch keine Bewertungen

- US Balance Exception Report White PaperDokument18 SeitenUS Balance Exception Report White PaperMarwan SNoch keine Bewertungen

- 122 0704Dokument35 Seiten122 0704api-27548664Noch keine Bewertungen

- Keynesian Vs Classical Models and PoliciesDokument18 SeitenKeynesian Vs Classical Models and PoliciesSarah Alviar-EismaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Applied EconomicsDokument6 SeitenApplied EconomicsAbet Zamudio Laborte Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- CANADA'S ECONOMIC ERAS: A BRIEF HISTORYDokument3 SeitenCANADA'S ECONOMIC ERAS: A BRIEF HISTORYseleneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends Networks Module 3Dokument35 SeitenTrends Networks Module 3Lee DanielNoch keine Bewertungen